Abstract

A 54-year-old woman presented with sudden epigastralgia and left back pain. She had no significant history. Laboratory data showed mild inflammation and no liver or renal dysfunction. Abdominal CT showed left adrenal enlargement and haemorrhage. Hydrocortisone therapy was started to prevent adrenal insufficiency before laboratory findings for ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) and cortisol levels. On the second hospital day, abdominal CT showed additional right adrenal enlargement and haemorrhage. The serum cortisol level suggested adrenal insufficiency. No specific findings were detected by bilateral adrenal angiography. 6 to 12 months later, abdominal CT showed decreased bilateral adrenal haemorrhage. This case illustrates the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment of acute adrenal insufficiency, and shows sequential changes in the size of bilateral adrenal haemorrhage. Rapid corticosteroid replacement is important if acute adrenal insufficiency is suspected. In a case with unilateral adrenal haemorrhage, the possibility of additional adrenal haemorrhage on the opposite side should also be considered.

Background

Adrenal haemorrhage has a variety of symptoms and causes.1–4 Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage with acute clinical manifestations is uncommon, but rapid aggravation of adrenal insufficiency is a potentially life-threatening event. We describe a case of acute adrenal insufficiency caused by bilateral adrenal haemorrhage that was followed up with serial imaging. This is a rare example of a case in which progression of adrenal haemorrhage was followed with imaging studies before and after onset.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old woman presented to the emergency department in our hospital with sudden epigastralgia and left back pain. She was positive for SS-A/Ro antibody and her daughter had been diagnosed with Sjogren syndrome, but the patient had no specific symptoms. She had no smoking or drinking habit. The results of a physical examination at the first visit were: height 154.4 cm, body weight 47.4 kg, blood pressure 147/88 mm Hg, heart rate 55 beats/min, body temperature 36.0°C and SpO2 99%.

Investigations

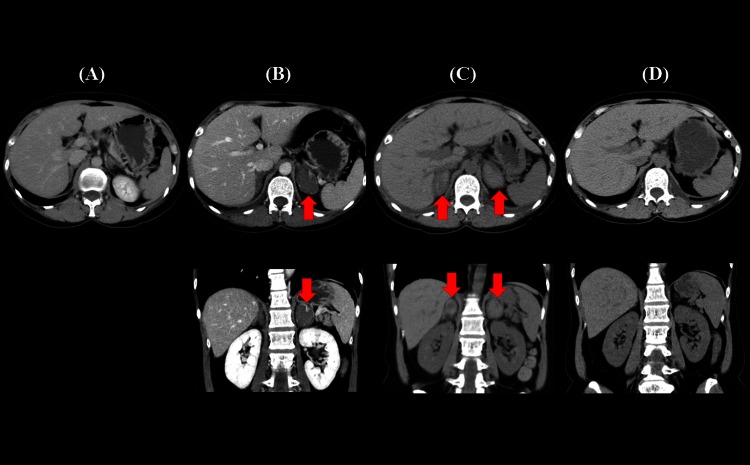

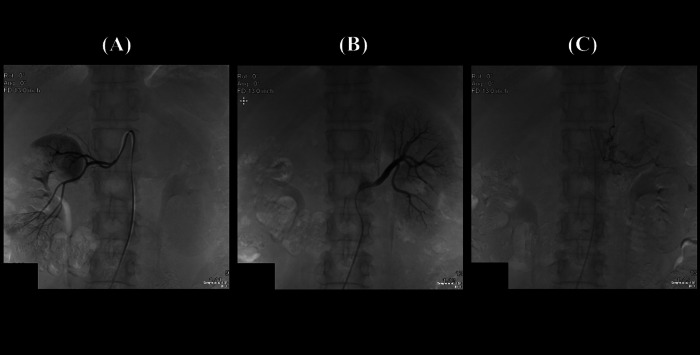

Laboratory data showed mild inflammation WBC 10420/µl, CRP (C-reactive protein) 0.76 mg/dl and no liver or renal dysfunction. ECG, chest and abdominal X-ray and gastroduodenal endoscopic examinations were close to normal. Chest and abdominal CT showed left adrenal thickening (figure 1A) compared with the right side. Her symptoms persisted for 2 days and abdominal CT performed for the second time revealed left adrenal enlargement (25×42×42 mm) and haemorrhage, and right adrenal gland thickening (figure 1B). On the second day after admission, abdominal CT showed right adrenal enlargement (20×36×34 mm) and haemorrhage, in addition to the condition on the left side (figure 1C). Hormonal data for the adrenal gland on the day of admission were adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) 26.5 pg/ml, cortisol 10.7 µg/dl at 3 pm, DHEA-S (dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate) 10 µg/dl, plasma renin activity 0.3 ng/ml/h, aldosterone 63 pg/ml, adrenalin ≤0.01 ng/ml, noradrenalin 0.17 ng/ml and dopamine 0.03 ng/ml (table 1). Basal hormonal levels and the daily profile of ACTH and cortisol after corticosteroid replacement suggested adrenal insufficiency (table 2). Bilateral adrenal angiography was performed with no specific findings (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan showing a thickened left adrenal grand (A) that was haemorrhagic and enlarged (B). Right adrenal haemorrhage was detected after left haemorrhage (C). Size reduction of the bilateral adrenal glands was shown by abdominal CT at 12 months after discharge (D).

Table 1.

Baseline laboratory data on admission

| WBC | 10700/µl | Ca | 8.6 mg/dl | PR3-ANCA | (–) |

| Neu | 77.8% | IP | 3.3 mg/dl | MPO-ANCA | (–) |

| Lym | 18.2% | CRP | 0.03 mg/dl | Anti-CLβ2GP1 | (–) |

| Mon | 3.3% | PT | 12.2 sec | Anti-CL | (–) |

| Eos | 0.3% | -INR | 0.98 | Lupus anticoagulant | (–) |

| Bas | 0.4% | aPTT | 32.8 sec | Soluble IL-2R | (–) |

| RBC | 4.76×106/µl | Fibrinogen | 341 mg/dl | Clioglobulin | (–) |

| Hb | 14.5 g/dl | FDP | <3 µg/ml | GH | 0.097 ng/ml |

| Plt | 23.4×104/µl | D-dimer | <0.5 µg/ml | LH | 16.5 mIU/ml |

| PPG | 163 mg/dl | U-glu | (–) | FSH | 58.9 mIU/ml |

| TP | 7.2 g/dl | U-p | (±) | PRL | 16.27 ng/ml |

| GOT | 21 IU/l | U-urobil | (–) | TSH | 3.297 µIU/ml |

| GPT | 15 IU/l | U-WBC | (–) | fT3 | 2.61 pg/ml |

| LDH | 230 IU/l | IgG | 1205 mg/dl | fT4 | 1.19 ng/dl |

| ALP | 313 IU/l | IgA | 193 mg/dl | Thyroglobulin | 19.8 ng/ml |

| γGTP | 12 IU/l | IgM | 83 mg/dl | Anti-thyroglobulin | (–) |

| T-Bil | 0.4 mg/dl | C3 | 110 mg/dl | Anti-TPO | (–) |

| CK | 95 IU/l | C4 | 30 mg/dl | ACTH | 26.5 pg/ml |

| Amylase | 45 IU/l | CH50 | 42 U/ml | Cortisol | 10.7 µg/dl |

| Lipase | 16 IU/l | ANA | 320 × | PRA | 0.3 ng/ml/h |

| BUN | 11.2 mg/dl | Anti-DNA Ab | (–) | Aldosterone | 63 pg/ml |

| Cre | 0.56 mg/dl | Anti-RNP Ab | (–) | DHEA-S | 10 µg/dl |

| UA | 2.2 mg/dl | Anti-SS-A Ab | 119 IU/l | Adrenalin | ≤0.01 ng/ml |

| Na | 139 mEq/l | Anti-SS-B Ab | (–) | Noradrenalin | 0.17 ng/ml |

| K | 3.8 mEq/l | Anti-Scl-70 Ab | (–) | Dopamine | 0.03 ng/ml |

| Cl | 105 mEq/l | Anti-Jo-1 Ab | (–) |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRP, C-reactive protein; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GH, growth hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; PRA, plasma renin activity; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Table 2.

Daily variation of adrenal hormones after administration of hydrocortisone

| 8 am | 2 pm | 8 pm | 2 am | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH (pg/ml) | 51.6 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Cortisol (µg/dl) | 5.9 | 17.4 | 14.0 | 5.4 |

| PRA (ng/ml/h) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Aldosterone (pg/ml) | 22 | 25 | 27 | 45 |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; PRA, plasma renin activity.

Figure 2.

Bilateral adrenal angiography showed no abnormalities. Right inferior adrenal artery branching from right renal artery (A), left inferior adrenal artery branching from left renal artery (B), left middle adrenal artery branching from abdominal aorta (C).

Differential diagnosis

Adrenal haemorrhage due to causes such as trauma, anticoagulation therapy, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, sepsis, antiphospholipid syndrome, hypertension, Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytoma, adrenal carcinoma, metastatic tumour, amyloidosis and malignant lymphoma was excluded.

Treatment

After hospitalisation, hydrocortisone therapy was started to prevent adrenal insufficiency before laboratory findings of ACTH and cortisol levels were obtained. The patient was initially treated with intravenous drip infusion of 200 mg of hydrocortisone per day and the dosage was gradually decreased. On hospital day 7, daily oral administration of 15 mg of hydrocortisone was started. The patient was hospitalised for 1 month.

Outcome and follow-up

A follow-up CT scan after discharge showed reduction in the size of bilateral adrenal haemorrhage (figure 1D). In parallel with this, repeated blood examinations showed improvement of ACTH and cortisol levels. The dosage of oral hydrocortisone replacement was gradually decreased and then stopped at 6 months after discharge.

Discussion

Adrenal haemorrhage is classified as traumatic or non-traumatic. Most cases of non-traumatic adrenal haemorrhage are related to stress due to infection, sepsis (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome), surgery, thermal injuries, coagulopathic and thromboembolic disorders, neonatal stress, adrenal tumours including metastasis or antiphospholipid syndrome, or are idiopathic.1–4

The exact mechanism of adrenal haemorrhage is unclear. Adrenal vascularities are referred to as an ‘adrenal dam’ because adrenal glands have sufficient vascularity, but easily become haemorrhagic and embolic because of their anatomical characteristics.5 This case was diagnosed as idiopathic adrenal haemorrhage after excluding other complications because angiography showed no vascular abnormalities of the adrenal glands.

Various clinical signs and symptoms occur in the early stages of adrenal haemorrhage, including sudden or gradual back pain, epigastralgia and non-specific conditions such as fatigue, fever, tachycardia, vomiting, nausea and dizziness.6 Hypotension or shock may indicate adrenal insufficiency.7 CT, MRI and ultrasonography are useful for diagnosis.8 Adrenal insufficiency may exhibit hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia and hypoglycaemia due to increased ACTH and decreased cortisol levels.9 Although most cases do not exhibit adrenal insufficiency, the condition sometimes deteriorates to an adrenal crisis and may be life-threatening. Thus, it is important to administer hydrocortisone promptly once adrenal crisis is suspected.9

In this case, hydrocortisone was administered before laboratory findings of ACTH and cortisol levels were obtained. Adrenal insufficiency is likely if a randomly timed measurement of serum cortisol is <15 μg/dl in critically ill patients.10 The patient in this case eventually had adrenal insufficiency because her cortisol level was low regardless of the stress condition. Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage developed as a potentially life-threatening disease, which occurs in the course of a variety of illnesses. For example, Rao11 reported a fatal outcome in 347 of 431 cases of bilateral adrenal haemorrhage.

In conclusion, we have described the case of a 54-year-old woman with bilateral adrenal haemorrhage that occurred on the right and left sides almost simultaneously. The cause of bilateral haemorrhage was idiopathic. Protection against adrenal insufficiency was attempted by early administration of hydrocortisone. CT was performed before adrenal haemorrhage on the right side, thus allowing evaluation of CT findings with progression after haemorrhage. This case also indicates that possible adrenal haemorrhage on the opposite side should be considered in a case with unilateral adrenal haemorrhage.

Learning points.

Sudden back pain or epigastralgia may be caused by adrenal haemorrhage.

Rapid replacement of corticosteroids is required in a case with suspected acute adrenal insufficiency.

Adrenal haemorrhage on the opposite side is possible in a case of unilateral adrenal haemorrhage.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Xarli VP, Steele AA, Davis PJ, et al. Adrenal hemorrhage in the adult. Medicine (Baltimore) 1978;2013:211–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberger LH, Smith PW, Sawyer RG, et al. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: the unrecognized cause of hemodynamic collapse associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Crit Care Med 2011;2013:833–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujishima N, Komatsuda A, Ohyagi H, et al. Adrenal insufficiency complicated with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Intern Med 2006;2013:963–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon DR, Palese MA. Clinical update on the management of adrenal hemorrhage. Curr Urol Rep 2009;2013:78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao RH, Vagnucci AH, Amico JA. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage: early recognition and treatment. Ann Intern Med 1989;2013:227–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharucha T, Broderick C, Easom N, et al. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage presenting as epigastric and back pain. J R Soc Med Short Rep 2012;2013:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picolos MK, Nooka A, Davis AB, et al. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: an overlooked cause of hypotension. J Emerg Med 2007;2013:167–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Ernest RD, et al. Imaging of nontraumatic hemorrhage of the adrenal gland. Radiographics 1999;2013:949–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouillon R. Acute adrenal insufficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2006;2013:767–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper MS, Stewart PM. Corticosteroid insufficiency in acutely ill patients. N Eng J Med 2003;2013:727–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao RH. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage. Med Clin North Am 1995;2013:107–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]