Abstract

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland is a rare aggressive malignancy. It is a rapidly advancing lesion which, if not recognised and treated early, results in high morbidity and mortality. Despite radical surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, prognosis of this cancer continues to be poor. Careful clinical and histological examination is mandatory to differentiate this tumour from metastatic squamous cell carcinoma and other primary malignancies of the parotid. The authors hereby report the case of a 50-year-old male patient who presented with a progressively increasing, painless mass in parotid region of 6 months duration. An initial fine-needle aspiration cytology and subsequent histopathological examination confirmed that the tumour was squamous cell carcinoma. As no other primary source could be demonstrated in the patient, a final diagnosis of primary squamous cell carcinoma of parotid was offered. Currently the patient is on regular follow-up without any signs of recurrence.

Background

The parotid glands are host to a diverse group of neoplasms having a wide spectrum of clinical, pathological and biological behaviour. Squamous cell carcinoma arising de novo from the parotid gland is a rare cancer comprising of less than 1% of all salivary gland neoplasms.1 More commonly, invasion from an adjacent squamous cell carcinoma or metastasis involves this major salivary gland; as such the possibility of these should always be excluded before labelling the parotid tumour as primary.1

We report the case of a 50-year-old man who presented with a progressively increasing, painless mass in parotid region of 6 months duration. An initial fine-needle aspiration cytology and subsequent histopathological examination confirmed that the tumour was squamous cell carcinoma. As no other primary source could be demonstrated in the patient, a final diagnosis of primary squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) of parotid was offered.

This case is being reported first to present the occurrence of this rare tumour of salivary gland. Second, a brief discussion of the differential diagnoses of tumours with squamous differentiation involving the parotid region is also undertaken herewith, about which both the treating physicians and pathologists need to be aware of.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old Indian non-smoker male presented with painless mass around his right angle of mandible which was progressively increasing over the last 6 months. There was no history of prior mass in the same region or in the neck. On examination, a tumour measuring about 6×4 cm was present in the right parotid region, firm to hard in consistency, non-tender, fixed to skin but free from deeper tissues. Overlying skin was nodular, although no ulcer was present. Features of facial nerve palsy were absent and cervical lymph nodes were not palpable. A provisional diagnosis of parotid tumour was made.

Investigations

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from the lesion showed few clusters of atypical squamoid cells having dense eosinophilic cytoplasm, raised nucleo-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio and anisonucleosis (figure 1). A diagnosis of carcinoma with squamoid differentiation was made and the patient was subjected to further workup for identifying the primary source. On enquiry, there was no history of cough, haemoptysis, difficulty in swallowing and hoarseness of voice. History of treatment for any cancer was also negative. Careful inspection of the skin of head, neck and scalp was performed to detect any tumour or ulcerative lesion—a possible source of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma which had metastasised to the parotid; however, no such lesions were observed. Straight x-ray chest and otorhinolaryngological checkups were within normal limits. CT scan of head and neck revealed a single tumour confined to the superficial lobe of the right parotid gland (figure 2). Under such circumstances, possibility of the primary source being the parotid itself was strongly considered and the patient underwent total parotidectomy with facial nerve preservation.

Figure 1.

Fine-needle aspirate showing small groups of atypical squamoid cells having raised N:C ratio, anionucleosis and dense eosinophilic cytoplasm. Background contains red blood cells and neutrophils (H&E, ×400).

Figure 2.

CT scan showing the tumour (yellow arrow) involving right parotid gland.

Gross examination of the specimen showed an irregular, hard tumour measuring 6×3.5 cm whose cut surface was tan white, solid with foci of necrosis and haemorrhage (figure 3). Microscopically, the tumour was composed of single population of moderately differentiated malignant squamous cells in nests and sheets inside a desmoplastic stroma (figure 4). Individual cells had increased N:C ratio, anisonucleosis, clumped chromatin, moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm with evidence of keratiniztion (figure 5). Intraparotid lymph nodes were free of tumour infiltration. In spite of extensive sampling, no other population of tumour cells could be observed and sections stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain were negative. With no other demonstrable primary source of origin, a final diagnosis of primary squamous cell carcinoma of parotid gland was offered.

Figure 3.

Gross photograph: cut section showing a tan white, solid tumour with irregular borders and foci of necrosis and haemorrhage (white arrows).

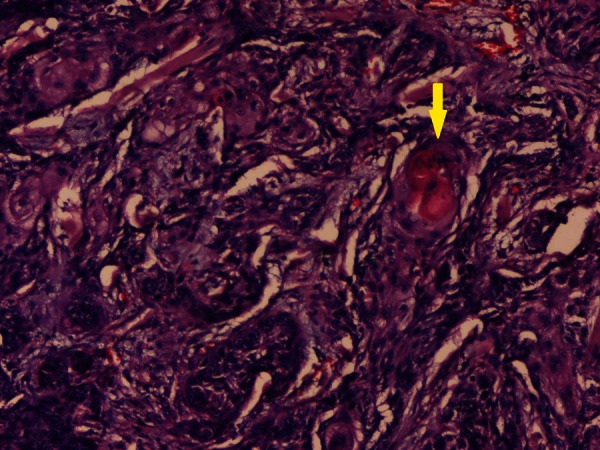

Figure 4.

Microphotograph of tissue section showing malignant squamous cells arranged in nests and sheets inside a desmoplastic stroma. Foci of keratin pearl formation is seen (yellow arrow) (H&E, ×100).

Figure 5.

Higher magnification showing moderately differentiated malignant squamous cells having increased N:C ratio, anisonucleosis, hyperchromasia, clumped chromatin and moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E, ×400).

Differential diagnosis

Apart from PSCC, the differential diagnosis of any tumour with squamous differentiation in the parotid region should include high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from a distant primary or a direct extension from an adjacent primary skin carcinoma. The incidence of parotid involvement by these tumours is greater than that of true PSCC.1–3 Hence, it is important to rule out these differentials before offering a diagnosis of PSCC.

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas (MEC) have predilection for women (male:female=2:3) and occur at a younger age (mean age 45 years) as compared with PSCC. MEC of low and intermediate grade seldom cause diagnostic confusion. High-grade MEC with predominant squamous component can be differentiated from PSCC on the basis of the fact that in MEC additional cell population in the form of mucin producing, basaloid and intermediate cells are detectable and prominent keratinisation is usually absent. Also, MEC stain positive for intracellular mucin with PAS or mucicarmine stains which are absent in PSCC.1 3 4 In our case, the patient was 50-year-old man. Histopathological examination from the tumour showed only one population of malignant squamous cells and PAS stain was negative in the tumour cells. So the probability of high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma was not considered.

Squamous cell carcinomas metastatic to parotid region can occur as direct extensions from tumours in external ear or periaural skin or as metastasis to the intraparotid and periparotid lymph nodes. In the latter scenario, the primary sites are frequently located in the upper aero-digestive tract and skin of the head and neck region.3 4 Hence, in the presence of synchronous or history of previous squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck region or upper aero-digestive tract, salivary gland involvement should be regarded more as metastatic than as primary. Also it is mandatory to inspect the skin of head, neck and scalp for any tumour or ulcerative lesion which might be a source of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with subsequent spread to parotid.3 Ying et al5 studied 66 patients with squamous cell carcinoma involving the parotid gland and found that 62% cases were metastatic tumours with known primary elsewhere in the body. In 24% cases, parotid was presumed to be the primary site as no other source was demonstrable, while in 14% cases, the origin remained undetermined. In context of the present case, focus of primary malignancy in any other organ could not be established from patient's history, clinical examination and investigations. As such, possibility of parotid being the secondary site was excluded.

Other rare salivary gland lesions that can be confused with PSCC are Warthin's tumour or oncocytoma with prominent squamous metaplasia, keratocystoma and necrotising sialometaplasia.1 2 From this discussion, it is quite imperative that the diagnosis of PSCC of salivary glands should always be offered only as a diagnosis of exclusion.

Treatment

Based on the initial workup results and FNAC report, the patient underwent total parotidectomy with facial nerve preservation. Following the histopathological examination and final diagnosis of PSCC, he received adjuvant radiation therapy in the form of 50 Gy of Co-60 teletherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient is doing well on follow-up, after 6 months of surgery and adjuvant radiation therapy, without any signs of recurrence.

Discussion

PSCC of salivary glands has been defined by WHO as ‘A primary malignant epithelial tumour composed of epidermoid cells, which produce keratin and/or demonstrate intercellular bridges by light microscopy’.1 This is an uncommon tumour accounting for less than 1% of all salivary gland neoplasms. Around 80% of the cases arise in the parotid gland while the rest are found in submandibular gland; sublingual gland is a highly unusual place of occurrence of this lesion.1 It is imperative to restrict the diagnosis of PSCC to major salivary glands only, because in squamous cell carcinoma of minor salivary glands, it is not possible to distinguish whether the tumour is arising from the glands themselves or from the adjacent mucosa.1 2

PSCC of parotid is an aggressive tumour of the elderly with a mean age of presentation at 64 years. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1. Prior radiation therapy has been implicated as a predisposing factor for PSCC. Patients typically present in an advanced stage with rapidly enlarging mass around the angle of mandible, often accompanied by cervical lymphadenopathy and facial nerve involvement.1 2 In the study by Gaughan et al,6 painful lump was documented in 33%, facial paralysis in 17% and cervical adenopathy in 11% cases of PSCC. Reports exist in literature where the first presentation of PSCC of parotid was in the form of acute facial paralysis which mislead to an initial suspicion of Bell's palsy.7

Fine-needle aspiration cytology is the preferred initial investigation in tumours of major salivary glands. The cytological features of PSCC of parotid are similar to squamous cell carcinoma arising anywhere in the body. However, it is imperative not to offer a diagnosis of PSCC on FNAC specimens because cytology alone cannot differentiate primary from metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Distinction from poorly differentiated mucoepidermoid carcinoma may also be impossible.8 Herein lie the importance of histopathological examination and clinical correlation in the diagnosis of PSCC.

Grossly, PSCC are solid, firm to hard, tan white tumours with infiltrative margins with occasional foci of necrosis on cut section. Histopathologically, most tumours are moderately to well differentiated squamous cell carcinomas with desmoplastic stroma and evidence of perineural invasion or soft tissue extension. Even though some cells may appear hydropic at times, intracellular mucin is absent and mucin stains are negative. Squamous metaplasia and dysplasia of adjacent salivary ducts are a common associated finding. Since these tumours are high-grade aggressive malignancies, concurrent cervical and intraparotid lymph node metastasis are frequently observed.1 2

On electron microscopy, the malignant cells of PSCC demonstrate numerous cytoplasmic processes and well-developed desmosomes. Majority of the cells contain intermediate filaments in their cytoplasm while secretory granules are absent. In doubtful cases, these ultrastructural findings are helpful in distinguishing PSCC from its close mimic mucoepidermoid carcinoma.9

PSCC of salivary glands is a high-grade aggressive malignancy which carries a worse prognosis than conventional squamous cell carcinoma. Age more than 60 years, ulceration, deep fixation, facial nerve involvement and cervical lymph node metastasis are associated with significantly poor prognosis.1 5 10 11 The treatment includes total parotidectomy with elective radical neck dissection, postoperative radiotherapy and periodic follow-up. In spite of adequate therapy, 5-year survival rate remains approximately at 25–30%.1 11

Learning points.

Primary squamous cell carcinoma arising in parotid gland is an extremely rare tumour accounting for less than 1% of all salivary gland neoplasms.

It is an aggressive malignancy with poor prognosis. Timely identification is of utmost importance in deciding treatment options and predicting outcome.

Tumours with squamous differentiation involving the parotid region are encountered more commonly owing to metastasis or contiguous spread from primary squamous cell carcinomas located elsewhere.

Primary squamous cell carcinoma must be kept in the differential diagnosis of any squamous cell carcinoma in parotid and its diagnosis should only be offered after its commoner mimics have been excluded.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lewis JE, Olsen KD. Squamous cell carcinoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005:245–6 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheuk W, Chan JKC. Salivary gland tumours. In: Fletcher CDM, ed. Diagnostic histopathology of tumours. 2nd edn Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2000:287–303 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taxy JB. Squamous carcinoma in a major salivary gland—a review of the diagnostic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001;2013:740–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Major and minor salivary glands. In: Rosai J, eds. Rosai and ackerman's surgical pathology. 10th edn Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier, 2011:836–37 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ying YLM, Johnson JT, Myers EN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck 2006;2013:626–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaughan RK, Olsen KD, Lewis JE. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;2013:798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam M, Gheriani H, Curran A, et al. Acute facial paralysis due to primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Ir Med J 2007;2013:568–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orell SR, Klijanienko J. Head and neck; salivary glands. In: Orell SR, Sterrett GF, eds. Orell & Sterrett's fine needle aspiration cytology. 5th edn New Delhi: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2012:70–1 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshihara T, Nomoto M, Hayasaki K, et al. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland: a case report with electron microscopic findings. Auris Nasus Larynx 1989;2013:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn MB, Maguire S, Martinez S, et al. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland: the importance of correct histological diagnosis. Ann Surg Oncol 1999;2013:768–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Kim GE, Park CS, et al. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Am J Otolaryngol 2001;2013:400–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]