Abstract

A 59-year-old man presented with hypohydrosis in his left upper extremity and left hand, and experienced difficulty in gripping the steering wheel while driving. One year prior to admission, he had felt pain and/or paresthesias in his left anterior chest, left shoulder area and left periaxillar area, which corresponded to involvement of dermatomes in T1–T3. He was diagnosed with Horner's syndrome caused by lung tumour, which was located at the apical posterior wall along with the second to fourth ribs. The tumour interrupted sympathetic neurons at the T1–T4 level. The degree of hypohydrosis was successfully evaluated by the starch–iodine technique, dermal thermography and a skin surface hygrometer. After radiation therapy, hypohydrosis and pain or paresthesias improved partially, and he was discharged uneventfully.

Background

Diagnosis of Horner's syndrome is typically based on history and clinical observation alone. Although anhydrosis and/or hypohydrosis is known to be one of the clinical symptoms of Horner's syndrome, it is difficult to assess the phenomenon quantitatively and qualitatively. Herein, we report a case of Horner's syndrome presenting with hypohydrosis on the tumour-affected side, and successfully performed evaluation using the starch–iodine technique, dermal thermography and a skin surface hygrometer, together with an illustration of representative sympathetic routes for the eyes, face and upper limbs.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old man was referred to our hospital with decreased sweating in his left upper extremity and left hand, as well as difficulty in gripping the steering wheel whenever he drove a car. One year prior to admission, he had felt pain and/or paresthesias in his left anterior chest, left shoulder area and left periaxillar area, which corresponded to the dermatomes of T1–T3. He also showed decreased left facial sweating for 6 months. He is a current smoker with a history of 40 pack-year.

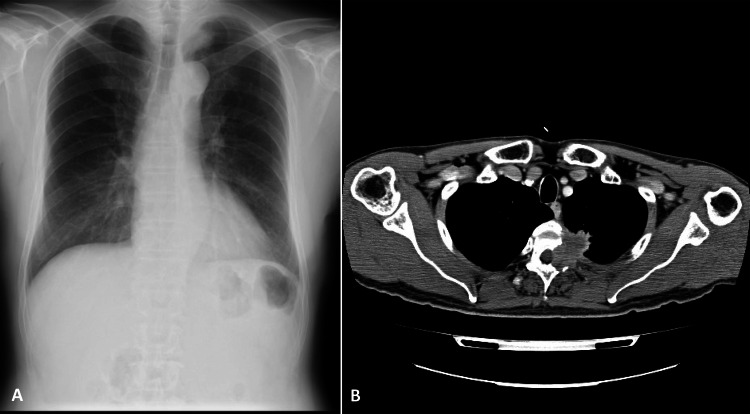

On physical examination, left constricted pupil (right: 3 mm; left: 2.5 mm) and ptosis and/or hypohydrosis in the left hemithorax were noted, suggesting Horner's syndrome. Light reflex was normal in both pupils. Neurologically, no sensory, thermic or pain deficits were noted. At the same time, chest x-ray (figure 1A) showed a mass in the left apical area measuring 3 cm in diameter. Contrast-enhanced thoracic CT (figure 1B) demonstrated a heterogeneous-enhanced mass as large as 3 cm located at the apical posterior wall along with the second to fourth ribs, which partially invaded the spinal canal area. He refused any invasive procedure, and was treated with radiation therapy under a tentative diagnosis of lung cancer T4N0M1b (Stage IV). Laboratory examinations were normal, except for mild elevation of serum squamous carcinoma antigen (1.9 ng/ml) and carcinoembryonic antigen (13.7 ng/ml).

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray (A) showing a mass in the left apical area measuring 3 cm in diameter. Contrast-enhanced thoracic CT (B) demonstrating a heterogeneously enhanced mass as large as 3 cm at the apical posterior wall, which partially invaded toward the spinal canal area.

Investigations

Further study with the starch–iodine technique1 (figure 2) confirmed localised hypohydrosis as a faint black colour on the left upper arm and left anterior chest, as compared with the right side (dense black colour). Dermal thermography (figure 3) clearly demonstrated increased body surface temperature in the left hand, left forearm and left upper arm, which corresponded to the hypohydrotic areas. Another method using a skin surface hygrometer (SKICON-200EX; I.B.S. Co., Ltd, Shizuoka, Japan), which is able to assess the hydration levels of the stratum corneum, showed that skin surface hydration (all data are presented as median values) was significantly lower (table 1, p=0.012) on the left upper side of the body than on the right side. Furthermore, body temperature at each site (forehead, neck, anterior chest, back, upper arm, forearm, palm and dorsum of the hand) was equal or greater on the left side than on the right side.

Figure 2.

Starch–iodine technique confirming localised hypohydrosis as faint black colour in the left upper arm and left anterior chest, as compared with the right side (dense black colour).

Figure 3.

Dermal thermography clearly demonstrating an increase in body surface temperature in the left hand, left forearm and left upper arm.

Table 1.

Assessment of skin surface hydration using by hygrometer with a result of body temperature

| Right side |

Left side |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin surface hydration (µS) | BT (°C) | Skin surface hydration (µS) | BT (°C) | |

| Forehead | 387 | 34.7 | 105 | 35.0 |

| Neck | 137 | 34.7 | 67 | 35.0 |

| Anterior chest | 255 | 34.6 | 72 | 35.2 |

| Back | 108 | 35.0 | 52 | 35.0 |

| Upper arm | 41 | 32.8 | 24 | 34.2 |

| Forearm | 60 | 32.7 | 20 | 33.2 |

| Palm | 570 | 34.1 | 10 | 34.7 |

| Dorsum of the hand | 153 | 33.4 | 50 | 33.6 |

BT, body temperature.

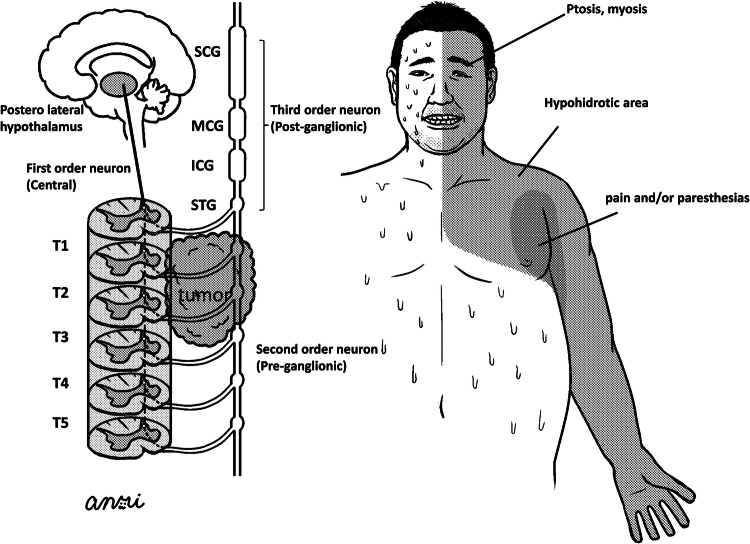

Figure 4 shows representative sympathetic routes for the eyes, face and upper limbs, as follows:

First-order neurons and second-order neurons (T1–T4)→superior cervical ganglion (SCG) or middle cervical ganglion (MCG)→third-order neurons to face or eyes

First-order neurons and second-order neurons (T3–T6)→inferior cervical ganglion (ICG) and/or superior thoracic ganglion (STG) (so-called stellate sympathetic ganglion)→third-order neurons to upper limbs

Figure 4.

Illustration of representative sympathetic routes for eyes, face and upper limbs.

Figure 4 shows that lung tumours interrupted sympathetic routes 1 and 2 at the level of second-order neurons (preganglionic) with hypohydrotic areas or paresthesias in the periaxillar area.

Outcome and follow-up

After radiation therapy, paresthesias in the left dermatomes of T1–T3, ptosis of the left eye lid and myosis partially improved, and he was discharged uneventfully.

Discussion

Horner's syndrome was first described by the Swiss ophthalmologist Johann Friedrich Horner,2 and is a collection of signs including myosis, ptosis, anhydrosis and enophthalmos due to interruption of the sympathetic pathways to the eyes and face, as was observed in the present case. The face and eyelids are supplied by spinal segments T1–4, the upper limbs, by spinal segments T2–8 and the trunk, by spinal segments T4–12.3 The present case showed that the tumour expanded vertically in T1–4, which is considered to be the source of hypohydrosis on the left side of the face, left arm and left upper thorax via interruption of sympathetic pathways at this level (figure 4). Furthermore, the patient experienced pain and paresthesias in the periaxillar area, which was thought to be the result of tumour invasion into the dorsal roots.

The three-neuron sympathetic pathway (figure 4), comprising of first-order (central), second-order (preganglionic) and third-order neurons (postganglionic), begins in the hypothalamus and ends in the eye. The most frequent causes of interruption of central neurons are infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery or distal vertebral artery occlusion producing lateral medullary syndrome, and preganglionic neurons are frequently interrupted by tumours (apical lung, mediastinal or thyroid),4 5 as was observed in the present case. Postganglionic fibres distributing from the internal carotid artery to the skull base consist of the internal carotid plexus and cavernous plexus, the former of which is vital for pleural innervation of the pupillary dilator muscle and ciliary muscle. The most common cause of interruption in postganglionic nerves is spontaneous or traumatic carotid artery dissection. Maloney et al6 reported 450 patients with Horner's syndrome, and 40% of cases had an unknown diagnosis, while the remaining 270 patients were divided into central (13%), preganglionic (44%) and postganglionic lesions (43%). Thus, irrespective of the interrupted portion, interrupted sympathetic nerves are able to cause Horner's syndrome.

There are few reports evaluating Horner's syndrome from the view of perspiration using the iodine–starch method.7–9 3 More importantly, these reports noted hypohydrosis/anhydrosis on the tumour-affected sympathetic nerve side and hyperhydrosis on the contralateral side,7 8 but hyperhydrosis on the tumour-affected side may occur via autonomic nerve stimulation by the tumour,9 3 which is known as ‘Reverse Horner Syndrome’.10 Although the mechanisms of hyperhydrosis (flushing or sweating) in Horner's syndrome on the tumour-affected side or the contralateral side are unknown, the present findings suggest that they are caused by irritation of sympathetic pathways via tumour invasion or localised overproduction of sweat on normal skin to compensate for an area of hypohydrosis.11 The present case suffered from difficulty in gripping the steering wheel while driving a car for a period of about 18 months, which has been caused by hypohydrosis in the left hand. Thus, dyshydrosis could precede clinical findings such as apparent ptosis or myosis, and might be presented as the first or sole symptom in patients with Horner's syndrome, as in the present case.

Learning points.

Horner’s syndrome can be a first and/or only clinical manifestation of lung cancer as was the present case.

Hypohydrosis/anhydrosis or hyperhydrosis (sweating/flushing) should be considered the first or sole clinical presentation of Horner's syndrome.

Horner's syndrome might not present as hypohydrosis/anhydrosis, but hyperhydrosis (so-called, reverse Horner's syndrome) even on the tumour-affected side.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH, DK, AI and TS have contributed equally by managing the patient and writing the manuscript of the case report.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sato KT, Richardson A, Timm DE, et al. One-step iodine starch method for direct visualization of sweating. Am J Med Sci 1988;2013:528–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Wiel HL. Johann Friedrich Horner (1831–1886). J Neurol 2002;2013:636–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slabbynck H, Bedert L, De Deyn PP, et al. Unilateral segmental hyperhidrosis associated with pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Chest 1998;2013:1215–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George A, Haydar AA, Adams WM. Imaging of Horner's syndrome. Clin Radiol 2008;2013:499–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kong YX, Wright G, Pesudovs K, et al. Horner syndrome. Clin Exp Optom 2007;2013:336–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maloney WF, Younge BR, Moyer NJ. Evaluation of the causes and accuracy of pharmacologic localization in Horner's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;2013:394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura J, Tamada Y, Iwase S, et al. A case of lung cancer with unilateral anhidrosis and contralateral hyperhidrosis as the first clinical manifestation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;2013:438–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munoz-Perez MA, Mazuecos J, Ortega M, et al. Guess what! Unilateral anhidrosis: first clinical manifestation of bronchial carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol 2001;2013:257–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jegarajah S, Coutts II. Localized sympathetic overactivity: an unusual complication of bronchogenic carcinoma. Br J Dis Chest 1977;2013:300–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole M, Berghuis J. The reverse Horner syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1970;2013:603–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalapesi FB, Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Segmental facial anhidrosis and tonic pupils with preserved deep tendon reflexes: a novel autonomic neuropathy. J Neuro Ophthalmol 2005;2013:5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]