Abstract

Infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with sickle cell disease. Loss of splenic function in these patients makes them highly susceptible to some bacterial infections. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections in patients with sickle cell disease are extremely rare and only two cases have been reported previously. We describe a case of sepsis caused by non-tuberculous mycobacterium, Mycobacterium terrae complex in a patient with febrile sickle cell disease. M terrae complex is a rare clinical pathogen and this is the first reported case of sepsis secondary to this organism in a patient with sickle cell disease. The patient responded to imipenem and amikacin therapy.

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a hereditary haemoglobinopathy associated with high morbidity and mortality. Infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with SCD. Many factors predispose these patients to infections, but the most important of these is the loss of splenic function which progresses from a reversible hyposplenic state early in the course of the disease to an asplenic state, when the spleen becomes atrophic due to repeated ischaemic damage caused by the sickled red blood cells. Impaired splenic function leads to a lack of IgM memory B-cells, which are essential for opsonisation of encapsulated bacteria. This impaired opsonophagocytic function predisposes patients with SCD to infections caused by encapsulated bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenzae.1 Studies have described additional mechanisms by which immunodeficiency occurs in patients with SCD. They include functional defects in the alternate complement pathway,2 zinc deficiency3 and polymorphisms of genes coding for human leukocyte antigen II subtypes.4 Sickled erythrocytes can also cause microvascular occlusion with the resultant ischaemic and necrotic tissue acting as a nidus of infection, which can spread to other parts of the body.5 Red cell exchange and long-term use of parenteral antibiotics require the use of implantable venous access devices, which can cause iatrogenic catheter-related infections, especially in adults.6 Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections in patients with sickle cell disease are extremely rare and only two cases have been reported previously. We describe a case of sepsis caused by non-tuberculous mycobacterium, M terrae complex in a patient with febrile sickle cell disease. M terrae complex is a rare clinical pathogen and this is the first reported case of sepsis secondary to this organism in a patient with SCD.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old African–American man with a history of SCD (SS phenotype) on periodic red cell exchange, iron overload and type 1 diabetes mellitus was hospitalised because of fever, generalised body pain and elevated fingerstick glucose >400 mg/dl. Medications at the time of admission included folic acid, hydroxyurea, hydromorphone and insulin.

Physical examination revealed temperature 99°F, heart rate 111 beats/min, respiratory rate 18/min, pallor and decreased air entry on the right side of the chest. No major joint swelling, erythema or tenderness was noted. Pertinent laboratory tests included total white blood cell count 16 500/mm3, absolute neutrophil count 12 300/mm3, haemoglobin 7.7 g/dl, reticulocyte count 6.9%, anion gap 16 mmol/l, urine ketones positive, ferritin 3682.0 ng/ml, glycated haemoglobin 13.1% and C-peptide <0.1 ng/ml. Portable chest x-ray revealed mild cardiomegaly and bilateral atelectasis of lungs. The patient was diagnosed with systemic inflammatory response syndrome because of heart rate >90 beats/min and white blood cell count >12 000/mm3. Other admitting diagnoses were diabetic ketoacidosis, anaemia and vaso-occlusive crisis.

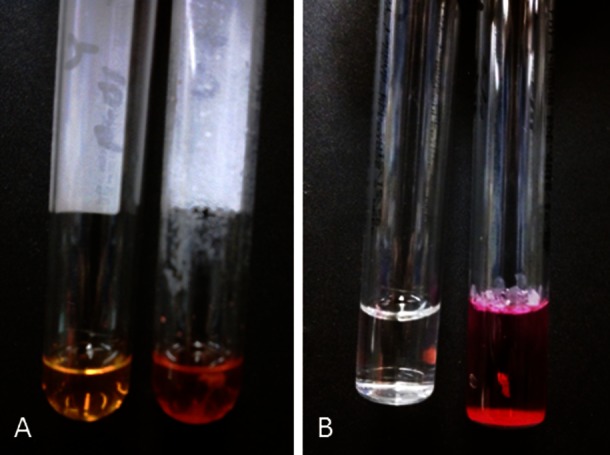

While hospitalised, the patient had intermittent spiking fevers. Blood cultures were requested; and broad-spectrum antibiotics, levofloxacin and linezolid, were started. After 4 days, three sets of routine blood cultures were positive. Gram stains revealed short beaded Gram-positive bacilli with similar morphology in smears from the three aerobic bottles; cooled Kinyoun acid-fast stain was positive (figure 1). The organism grew on Lowenstein Jensen slants in 8 days. The colonies were buff coloured with no pigmentation after exposure to light. Nucleic acid hybridisation-based assays (AccuProbe, Gen-Probe, CA, USA) were performed for culture identification. Chemiluminescent labelled single-stranded DNA probes complementary to ribosomal RNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium gordonae and Mycobacterium kansasii were used. The luminometer readings for all four probes were below the cut-off values, indicating that no stable hybrids were formed; so the cultures were negative for these organisms. A panel of biochemical tests was performed. The organism was positive for catalase production at pH 7, Tween 80 hydrolysis (figure 2A) and arylsulfatase after 3 days (figure 2B). These findings were consistent with M terrae complex.

Figure 1.

Kinyoun acid-fast stain of the blood cultures showing short beaded bacilli (×1000).

Figure 2.

Tween 80 hydrolysis: yellow-negative control (left), red-positive patient (right) (A). Arylsulfatase test: clear-negative control (left), red-positive patient (right) (B).

Treatment

The patient at the time of admission was empirically started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, levofloxacin and linezolid. Based on the culture results, antibiotic therapy was changed to imipenem and amikacin and the patient responded after 2 weeks of therapy.

Discussion

Infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) has only been rarely described in SCD patients. To our knowledge, disseminated NTM infection in SCD patients was described only once before as a case report.7 This case report describes a 13-year-old girl and a 15-year-old girl with central venous catheters on hydroxyurea developing disseminated Mycobacterium fortuitum infections. We present the first case of a bloodstream infection due to M terrae complex in an SCD patient. Members of the M terrae complex are rare human pathogens known to cause pulmonary, bone and joint infections.8

Disseminated NTM infections are most commonly seen in HIV-positive patients usually having CD4+ T-cells <50/µl.9 They are also occasionally seen in patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs, renal or cardiac transplant recipients, patients taking high-dose corticosteroids on a chronic basis and Leukaemic patients.9 A positive feedback loop between interleukin-12 (IL-12) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) is responsible for control of certain intracellular infections including those caused by mycobacteria. Specific mutations of the pathways constituting this feedback loop can also cause disseminated NTM infections.10

In addition to SCD, three factors, which could have predisposed this patient to bloodstream infection due to M terrae complex, are type 1 diabetes mellitus, iron overload and hydroxyurea therapy.

An important risk factor for infection in this patient is diabetes mellitus. Patients with diabetes have increased incidence of infections due to bacteria, fungi and mycobacteria. Tuberculosis and NTM infections are increased in patients with diabetes. NTM infections most often involve the lungs, skin and soft tissue with only rare cases of sepsis. In an epidemiological study of 119 non-HIV-positive patients with NTM infections, only seven had bloodstream infections with two of these patients with diabetes mellitus.11 These infections could be due in part to defective T-cell proliferation in response to infection in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.12 Another study in patients with type 1 diabetes showed decreased IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes, which increases the risk of infection due to intracellular pathogens.13

Another risk factor in our patient could be iron overload. Previous liver and bone marrow biopsies in our patient showed markedly increased iron deposits in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and marrow reticuloendothelial cells. Serum ferritin at the time of admission was markedly elevated. Iron overload of macrophages causes macrophage and T-cell dysfunction due to decreased production of IFN-γ, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-12 and nitric oxide (NO).14 Cytotoxic effect in response to IFN-γ is lost, predisposing to infections caused by intracellular pathogens including mycobacteria.15

A third somewhat controversial factor to be considered is the effect of hydroxyurea (HU) on cell-mediated immunity in SCD patients. HU is a ribonucleotide reductase enzyme inhibitor that induces the expression of dormant fetal haemoglobin (HbF) genes by incompletely understood mechanisms. HU increases the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and NO levels and improves the red blood cell hydration, all of which are therapeutically beneficial in patients with SCD. HU also has cytotoxic effects of myelosuppression and reticulocytopaenia.16 Decreased white blood cell counts are beneficial in SCD because neutropoenia can prevent vaso-occlusion that occurs due to pathological adhesion between endothelial cells and neutrophils.17 So, while immunosuppression due to myelosuppression is an expected toxicity of HU, many studies, including the BABY HUG trial (NCT00006400) have concluded that infection due to HU is not a major cause of concern in both adult and paediatric patients with SCD.18 19 However, a review of data from three other cases in the literature show that immunosuppression due to HU may have been responsible for the development of opportunistic infections like Cryptosporidium gastroenteritis,20 Plesiomonas shigelloides sepsis21 and disseminated M fortuitum infections in the two paediatric patients.7 Other studies have also shown that HU may cause a cytostatic effect on CD4+ T-cells22 and interfere with the Th-1 cell-mediated immune response. Moreover, with increasing evidence of the efficacy of HU in preventing SCD-related clinical events, more extensive use in all age groups will likely occur. Healthcare providers should keep in mind the effects of HU on myelosuppression and CD4+ T cell counts; however, HU role in the development of unusual infections in SCD patients is still unknown.

In this patient, SCD complicated by diabetic ketoacidosis contributed to the development of sepsis by a usually non-pathogenic NTM. Iron overload leading to macrophage dysfunction was also a contributing factor. The role of HU therapy in the development of opportunistic infections in SCD patients is not clear and more studies are needed to see if there is an association.

Learning points.

Infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in sickle cell disease (SCD) patients, most often related to loss of splenic function and microvascular occlusion.

Unusual opportunistic pathogens may be encountered when SCD patients have comorbid conditions such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and iron overload.

Iron overload is common in patients with SCD and leads to macrophage and T-cell dysfunction, predisposing to infections with unusual pathogens.

The role of hydroxyurea therapy in the development of opportunistic infections in patients with SCD is not clear and more studies are needed to see if there is an association.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKE and SKM were involved with collection of the clinical information and preparation of the draft. TJN and PAO reviewed and revised the draft related to their areas of specialty. All the authors have reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brendolan A, Rosado MM, Carsetti R, et al. Development and function of the mammalian spleen. Bioessays 2007;2013:166–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larcher VF, Wyke RJ, Davis LR, et al. Defective yeast opsonisation and functional deficiency of complement in sickle cell disease. Arch Dis Child 1982;2013:343–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuvibidila SR, Sandoval M, Lao J, et al. Plasma zinc levels inversely correlate with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 concentration in children with sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;2013:1263–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamouza R, Neonato MG, Busson M, et al. Infectious complications in sickle cell disease are influenced by HLA class II alleles. Hum Immunol 2002;2013:194–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins BL, Price EH, Tillyer L, et al. Salmonella osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease children in the east end of London. J Infect 1997;2013:133–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarrouk V, Habibi A, Zahar JR, et al. Bloodstream infection in adults with sickle cell disease: association with venous catheters, Staphylococcus aureus, and bone-joint infections. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;2013:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorell EA, Sharma M, Jackson MA, et al. Disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in sickle cell anemia patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2006;2013:678–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlossberg D. Tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. 6th edn Washington, DC: ASM press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horsburgh CR., Jr Epidemiology of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Semin Respir Infect 1996;2013:244–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casanova JL, Abel L. Genetic dissection of immunity to mycobacteria: the human model. Annu Rev Immunol 2002;2013:581–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodle EE, Cunningham JA, Della-Latta P, et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients without HIV infection, New York City. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;2013:390–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spatz M, Eibl N, Hink S, et al. Impaired primary immune response in type-1 diabetes. Functional impairment at the level of APCs and T-cells. Cell Immunol 2003;2013:15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avanzini MA, Ciardelli L, Lenta E, et al. IFN-gamma low production capacity in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients at onset of disease. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2005;2013:313–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pieracci FM, Barie PS. Iron and the risk of infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2005;2013(Suppl 1):S41–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan FA, Fisher MA, Khakoo RA. Association of hemochromatosis with infectious diseases: expanding spectrum. Int J Infect Dis 2007;2013:482–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware RE. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2010;2013:5300–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benkerrou M, Delarche C, Brahimi L, et al. Hydroxyurea corrects the dysregulated L-selectin expression and increased H(2)O(2) production of polymorphonuclear neutrophils from patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2002;2013:2297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg MH, McCarthy WF, Castro O, et al. The risks and benefits of long-term use of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia: a 17.5 year follow-up. Am J Hematol 2010;2013:403–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornburg CD, Files BA, Luo Z, et al. Impact of hydroxyurea on clinical events in the BABY HUG trial. Blood 2012;2013:4304–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venigalla P, Motwani B, Allen S, et al. A patient on hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease who developed an opportunistic infection. Blood 2002;2013:363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tzanetea R, Konstantopoulos K, Xanthaki A, et al. Plesiomonas shigelloides sepsis in a thalassemia intermedia patient. Scand J Infect Dis 2002;2013:687–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zala C, Rouleau D, Montaner JS. Role of hydroxyurea in treatment of disease due to human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2000;2013(Suppl 2):S143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]