Abstract

On review of past 10 years medical records, we could find four typical cases of porphyria with rare ocular manifestations. Cases 1, 2 and 4 have presented with features suggestive of acute scleritis. Based on clinical, biochemical and dermatological evaluation, all these three cases were diagnosed to have congenital erythropoietic porphyria. Case 1 was initially managed with scleral patch graft which on subsequent melt was managed with double layered amniotic membrane grafting along with conjunctival advancement and lateral paramedian tarsorrhaphy in both the eyes. Cases 2 and 4 were managed conservatively with artificial tear drops and general protective measures. Case 3 was presented with multiple failed grafts due to repeated ulceration and infection. Owing to multiple failed grafts, Boston keratoprosthesis was done and the patient is doing well with stable kertaoprosthesis at the last follow-up visit.

Background

Porphyria is a rare metabolic disorder that is characterised by the accumulation of photosensitive, toxic intermediates of the haeme metabolic pathway in various organs of the body including the skin, eye and neural tissue.1 Eye involvement in porphyria is exceedingly rare and may manifest as lid scarring, ectropion,2 pingueculae, pterygium,3 acute scleritis with scleral necrosis,5 6 corneal thinning and corneal perforation.7 On review of past 10 years medical records at this tertiary care centre, we could find only four cases of porphyria with ocular complications. Herein, we report these four typical cases of porphyria with rare ocular manifestations and their subsequent management.

Case presentation

Case 1

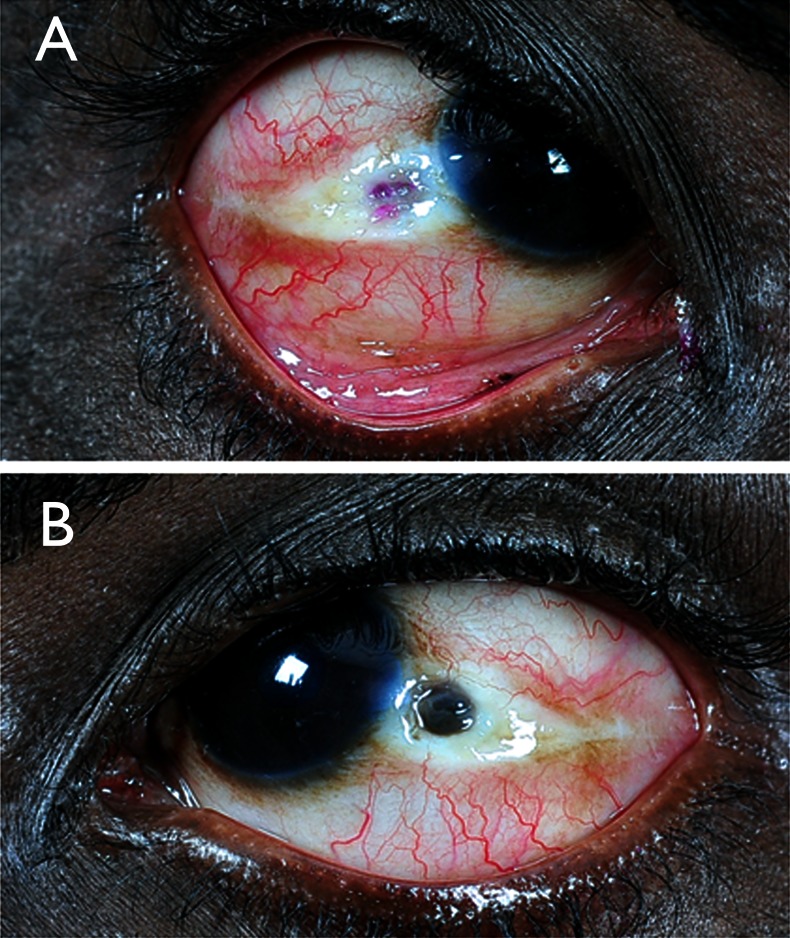

A 33-year-old man, born of consanguineous parentage reported with history suggestive of bilateral scleral thinning for 1 year. The patient's visual acuity was 20/20, N6 in both eyes. Ocular examination showed focal, circular, crater-like, areas of scleral thinning in the interpalpebral area, 2 mm temporal to the limbus in both eyes (figure 1A,B). The scleral thinning was more marked in the left eye with uveal prolapse. The anterior chambers were quiet. Dilated examination of fundi was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

Right eye (A) shows an area of scleral necrosis and thinning whereas left eye (B) shows an area of scleral necrosis and uveal prolapse.

He reported a history of excretion of red urine for 1 year. His exposed areas like face (figure 2), hands and feet showed diffuse hyperpigmentation with thickening of skin.

Figure 2.

Face shows hyperpigmentation, scarring and thickening of skin.

Case 2

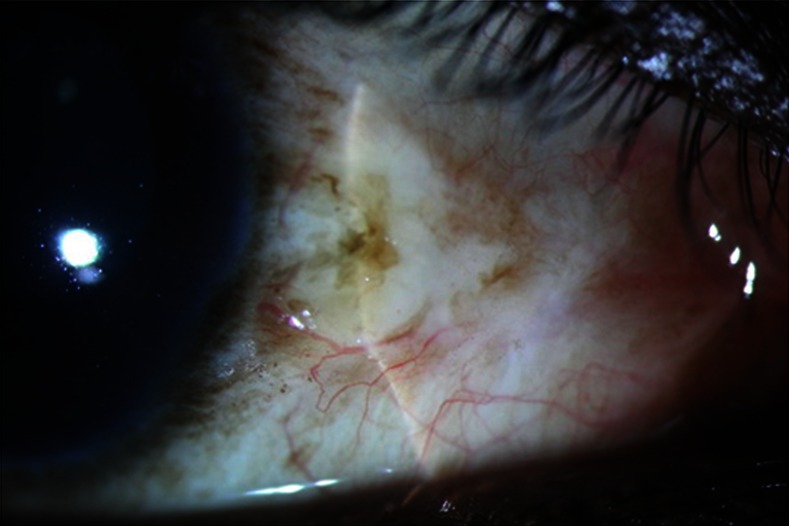

A 29-year-old man, born of consanguineous parentage reported with history suggestive of scleral thinning in left eye for 1 month. The patient's visual acuity was 20/20, N6 in left eye. He has ocular prosthesis in the right eye. Ocular examination of the left eye showed focal, circular, crater-like, area of scleral thinning similar to case 1 (figure 3). He reported a history of excretion of red urine for 3 years. His exposed areas showed features similar to case 1.

Figure 3.

Right eye shows an area of scleral necrosis and thinning.

Case 3

A 56-year-old man, a known diabetic and hypertensive, born of non-consanguineous parentage reported at our institute with a history suggestive of multiple failed grafts in the right eye. His left eye was phthisical. His clinical, biochemical and dermatological evaluation suggestive of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) along with management and subsequent follow-up has been described in case report published online in BMJ Case Report.4

Case 4

An 18-year-old man, born of non-consanguineous parentage reported an acute onset of redness and pain in the right eye in 2000. The patient's visual acuity was 20/20, N6 in both eyes. His clinical, biochemical and dermatological evaluation suggestive of congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) along with management and subsequent follow-up has been described in case report published in ‘Cornea’ in 2001.5

Investigations

Case 1

Suspecting porphyria, we evaluated his urine, blood, stool and skin. The urine was red on standing and emitted red fluorescence under UV light. Spectroscopic analysis of the urine showed absorption spectra at 422.6 nm and emission spectra at 615 nm, indicating increased excretion of urinary porphyrins. Serum analysis showed increased protoporphyrin level, whereas stool examination showed increased levels of both protoporphyrin and coproporphyrin levels. Skin biopsy showed periodic acid Schiff PAS) positive material in papillary dermis which appears to be diastase resistant. Based on the clinical, biochemical and dermatological evaluation, a diagnosis of CEP was made.

Case 2

Suspecting porphyria, we evaluated his urine, blood, stool and skin and findings are similar to case 1. Based on the clinical, biochemical and dermatological evaluation, a diagnosis of CEP was made.

Treatment

Case 1

Considering scleral melt with uveal prolapse, it was decided to schedule the left eye for scleral patch graft and to start artificial tear drops (Tears Naturale Free, Alcon, Texas, USA) and a topical broad spectrum antibiotic (Chloramphenicol ophthalmic; AK-Chlor) in both the eyes. A 4×4 mm scleral patch grafting along with advancement of both tenon capsule and conjunctiva was performed in order to cover the sclera patch graft and he was kept on tapering dosage of topical steroid along with lubricants. A month later, the patient reported with melt around scleral patch graft. However, the uveal tissue was well epithelialised; hence it was decided to keep the patient under observation.

Six months later, the patient presented with prolapsed unepithelialised uveal tissue. At this stage, the patient underwent double-layered amniotic membrane grafting along with conjunctival advancement and lateral paramedian tarsorrhaphy in both the eyes to promote healing. He was also started with topical lubricants.

Case 2

Considering mild scleral thinning in the left eye, it was decided to have a conservative approach in the patient with artificial tear drops (Tears Naturale Free) and a topical broad spectrum antibiotic (Chloramphenicol ophthalmic; AK-Chlor). The patient was advised to keep away from sunlight and to use protective goggles and apply skin ointment lotion when going outdoors.

Outcome and follow-up

Case 1

Four months later, his condition was stable and was on lubricants and a close follow-up.

Case 2

Six months later, his condition was stable and was on lubricant with a close follow-up.

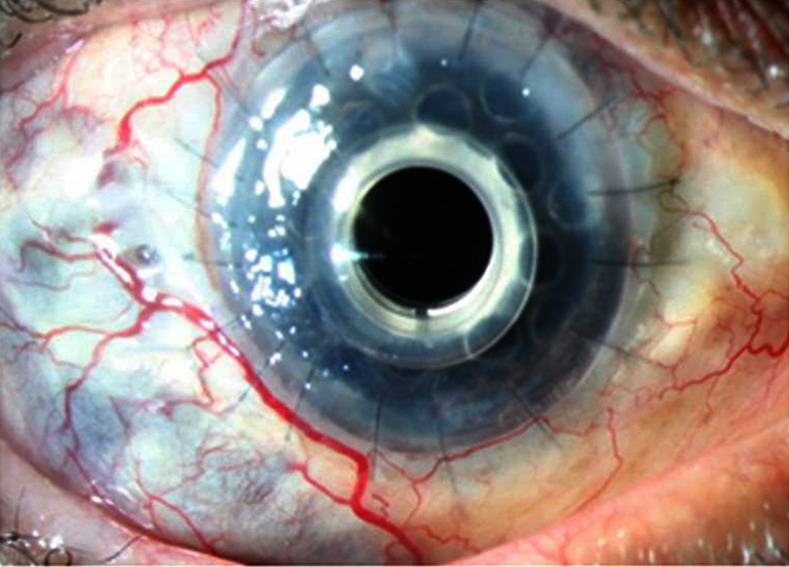

Case 3

He was again reviewed in February 2013. Twelve months after the procedure, the patient is highly contended with his best corrected vision as 20/120 (due to changes at retinal pigment epithelium secondary to cystoid macular oedema) with stable Boston keratoprosthesis (figure 4). At present, he is on topical antibiotics (moxifloxacin eye drops 10 times a day and chloromaphenicol eye drops 6 times a day), topical steroid (eyedrops Predforte acetate 1%) in tapering dosage, topical lubricant (Tears Naturale Free;) and a three-monthly follow-up. Moreover, the patient was advised to take general protective measures for the exposed parts of the body.

Figure 4.

Stable keratoprosthesis at the last follow-up visit.

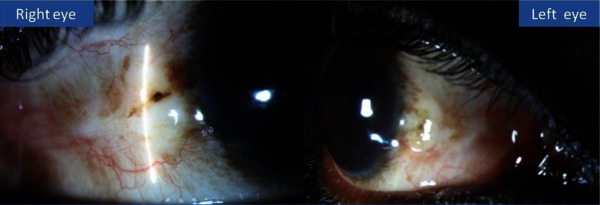

Case 4

He has been on regular follow-up since diagnosed and is on topical lubricant. He was last seen in January 2013 and is doing well with no evidence of ocular recurrence (figure 5). The patient is currently on topical lubricant along with general protective measures.

Figure 5.

Stable ocular surface at the last follow-up visit.

Discussion

Porphyrias are classified as erythropoietic or hepatic based on the defects of specific enzymes in the haeme synthesis pathway, the exact diagnosis being made by estimation of defective enzyme, or the accumulated precursors in haeme synthesis.8 They are also classified as either acute or cutaneous, reflecting the primary clinical manifestations. An appreciation that the different porphyrias display great diversity in their clinical manifestations is a key to understanding these disorders. PCT, the most common form of porphyria,9 is a metabolic disorder that is caused by reduced activity of the enzyme uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (Uro-D) in the liver. In CEP,5 an autosomal recessive disorder, the enzyme defective is uroporphyrinogen III synthase (URO synthase) leading to accumulation of URO I porphyrins in urine and blood. The bright red fluorescence in our cases helped us differentiate it from PCT. Clinical manifestations are predominantly dermatological; however, rarely ocular complications occur as described above.

The exact mechanism by which ocular damage occurs in porphyria is still unclear; however, photic damage, ischaemia and inflammation secondary to accumulation of porphyrins has been stipulated as the underlying cause.10

What we believe is that the presence of porphyrin precursors in the tears incites inflammatory response secondary to phototoxicity. It is this inflammatory response that manifests as acute scleritis with scleral necrosis, corneal thinning and corneal perforation in the interpalpebral area.

Management depends upon the type of presentation. If the patient presents at an early stage as in case 2, it is better to instil copious lubricant along with general protective measures. Scleral patch graft is mandatory to restore globe integrity as seen in case1. Considering the poor fate of grafts, as in case 3, Boston keratoprosthesis has emerged as a viable option, though a long-term follow-up is required. It is quiet surprising to us that even after 10 years, case 4 is doing well with no further intervention. What actually triggers these recurrences is yet to be explored. We suggest long-term genetic studies to better understand the long-term history of the disease.

These case reports highlight the rare ocular complications of porphyria which are sparingly described in literature. Moreover, the studies on the long-term follow-up results are fewer. Despite careful follow-up and intensive treatment, scleral and corneal necrosis can be progressive and results in the loss of vision or even the loss of eye. Further studies regarding the care of patients with porphyrias are required to treat these rare ophthalmic conditions more effectively.

Learning points.

Ocular complications of porphyria are rare, and occurrence of complication like corneal ulceration and infection is even rarer.

Corneal ulceration and scleral necrosis occur due to phototoxicity as a result of deposition of porphyrin precursors.

Management strategies vary, but mainly include scleral patch graft for scleral necrosis and Boston keratoprosthesis for repeated corneal ulceration and infection.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS, SB and VS were involved in conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. AS and VS contributed to drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content.. VS did the final approval of the version published..

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Venkatesh P, Garg SP, Kumaran E, et al. Congenital porphyria with necrotizing Scleritis in a 9-year-old child. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000;2013:314–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sober AJ, Grove AS, Muhlbauer JE. Cicatricial ectropion and lacrimal obstruction associated with the sclerodermoid variant of porphyria cutanea tarda. Am J Ophthalmol 1981;2013:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammer H, Korom I. Photodamage of the conjunctiva in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Br J Ophthalmol 1992;2013:592–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sati A, Sangwan VS, Basu S, et al. Boston keratoprosthesis for visual rehabilitation in porphyria cutanea tarda. BMJ Case Rep 2013 Feb 1; 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veenashree MP, Sangwan VS, Vemuganti GK, et al. Acute scleritis as a manifestation of congenital erythropoietic porphyria. Cornea 2012;2013:530–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altiparmak UE, Oflu Y, Kocaoglu FA, et al. Ocular complications in 2 cases with porphyria. Cornea 2008;2013:1093–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaborowski AG, Paulson GH, Peters AL. Sight threatening complications in porphyria cutanea tarda. Eye 2004;2013:949–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer UA. Porphyria. In: Braunwald E, Issebacher KJ, Petersdorf RG, et al. eds. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 13th edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994:2073–9 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yachimski P, Shah N, Chung RT. Porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;2013:e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddique SS, Gonzalez LA, Thakuria P, et al. Scleral necrosis in a patient with congenital erythropoietic purpura. Cornea 2011;2013:97–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]