Abstract

We describe a case of a 40-year-old lady diabetic and hypertensive, who presented with increasing fatigue and decreased physical endurance attributable to deterioration in renal function. The renal biopsy revealed drug-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and the chronology of the events suggested the aetiology to be a recent intake of aceclofenac for knee pain. The patient improved with oral corticosteroids and the renal functions returned to baseline in 3 weeks. We did not come across a case of aceclofenac-induced acute tubulointerstitial nephritis on extensive electronic search of literature. This is probably the first case report of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with the use of aceclofenac, a newer potent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Background

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) due to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is a well recognised albeit uncommon adverse drug event in medical literature. Still these analgesics are over prescribed by the medical practitioners and also consumed rampantly by the patients for fever, minor aches and pains. In addition, a large section of the population follows the principle of self-treatment with these analgesics due to the convenient over-the-counter availability of these drugs. Most of the consumers are oblivious of the serious adverse effects of these seemingly innocuous painkillers and ultimately end up with life-threatening consequences like upper gastrointestinal bleeding and acute kidney injury. We are highlighting here a case of biopsy-proven ATIN in a patient who was unaware of a similar ‘harmless’ painkiller. This case illustrates that constant pharmacovigilance is the key to detect such rare events, even in those drugs projected to have a favourable profile.

Case presentation

The index case was a 40-year overweight lady who had diabetes and hypertension since 7 years. She was on sitagliptin 100 mg per day and metformin 2000 mg per day for last 1 year and her diabetes control was satisfactory. Hypertension was well controlled on losartan 100 mg per day. Three months prior to admission her serum creatine was 0.9 mg/dl, urine was negative for microalbumin and fundus examination did not reveal diabetic retinopathy. For the past 1 week patient had noticed increasing fatigue, decreased body endurance, malaise and nausea. There were no complaints of arthralgia, skin rash, polyuria or oliguria, fever or jaundice, dyspepsia or heartburn. There was no history suggestive of connective tissue disease or any recent pharyngeal or cutaneous infection. Treatment history disclosed that she had consumed 5–6 tablets of aceclofenac sustained release 200 mg over a week for knee pain around 2 weeks back. She was also not using any complementary alternative medicine. On examination she was pale, afebrile and had normal blood pressure and pulse. There was no rash, icterus, facial or pedal oedema, organomegaly or lymphadenopathy and no renal bruit.

Investigations

Investigations were carried out to ascertain the cause of generalised weakness. Her haemoglobin was 9.5 g/dl, normocytic normochromic. Leucocyte and platelet indices were normal. Blood urea was 98 mg/dl, serum creatine 5.5 mg/dl, serum sodium, potassium, calcium and phosphorus 135 meq/l, 5 meq/l, 8.5 mg/dl, 4.2 mg/dl, respectively. The fasting and postprandial glucose were 110 mg/dl and 138 mg/dl, glycated haemoglobin was 6.7%. The arterial blood gases did not show any metabolic acidosis.

Antinuclear antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative by immunofluorescence. C3 levels were within normal range. The urine microscopic showed few eosinophils and no overt proteinuria. However, there was evidence of microalbuminuria; the urine albumin to creatine ratio (UACR) being 46 mg/g. The abdominal ultrasonography revealed bilateral normal sized kidneys with no evidence of renal artery stenosis or renal vein thrombosis. A renal biopsy was done subsequently.

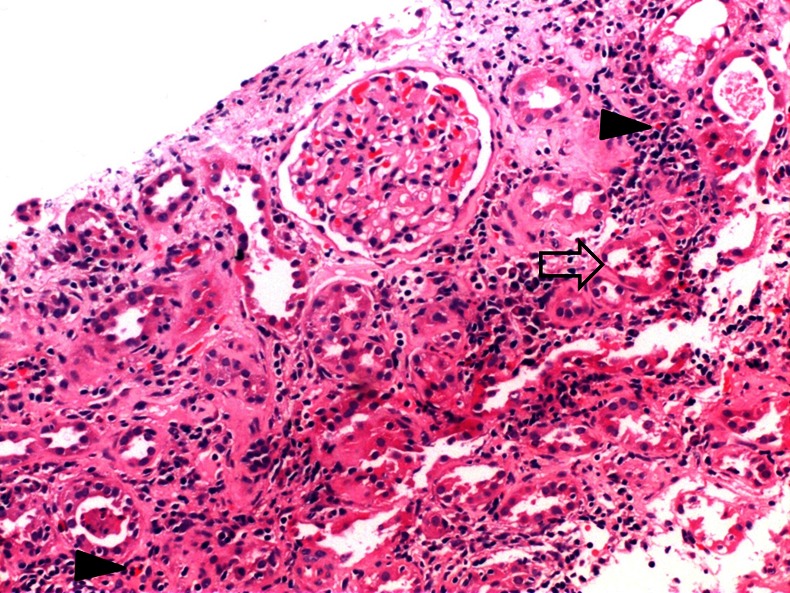

Renal histopathology (light microscopy) specimen showed a total of 10 glomeruli, all normal. The interstitium showed moderate to dense inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphomononuclear cells and eosinophils (figure 1). Focal tubular atrophy was seen with interstitial fibrosis. The histopathology was consistent with ATIN. Renal biopsy specimen was also subjected to immunoflourescence. Direct immunoflourescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, κ and λ and C1q. Electron microscopic examination of kidney biopsy showed focal effacement of podocyte foot processes suggestive of diabetic nephropathy. The glomerular capillary walls were thickened with loss of trilaminar structure. Focal fibrillary change was noted in mesangium and glomerular basement membrane. There were no immune complex type electron dense deposits.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph (H&E ×100) showing acute tubulitis (blank arrow) along with interstitial oedema and mixed inflammatory infiltrate with the presence of scattered eosinophils (solid arrow), the glomeruli being unremarkable.

Differential diagnosis

We based our diagnosis of aceclofenac-induced ATIN on the features of acute onset azotaemia, eosinophiluria, renal interstitial oedema and inflammation with eosinophilic infiltrates and temporal association of drug/disease. However, in the above clinical scenario, we considered other differentials of non-diabetic renal disease such as acute pyelonephritis, acute glomerulonephritis/crescentic glomerulonephritis. Histopathology on renal biopsy was helpful in confirming our clinical suspicion of ATIN.

Treatment

Aceclofenac was withdrawn. The patient was managed with corticosteroids which were initiated with prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day, continued for 4 weeks and then tapered slowly in next 4 weeks. All other drugs were also withdrawn and she was put on premixed insulin twice daily subcutaneously.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient's symptoms and renal parameters showed rapid recovery and then continued to steadily improve and creatine touched baseline at the end of 3 weeks after initiation of steroids. She continues to have normal renal functions even after complete steroid cessation. The patient was restarted on metformin in addition to the insulin regime and losartan for hypertension after her renal functions normalised. She has been on close follow-up and there has been no worsening of renal parameters on these drugs. Currently her routine urine examination is normal and the UACR is 18 mg/g.

Discussion

The term ATIN describes a pattern of renal injury usually associated with an abrupt deterioration in renal function characterised histopathologically by inflammation and oedema of the renal tubules and interstitium.1 The term was first used by Councilman in 1898 for histopathological changes in autopsy specimens of patients with diphtheria and scarlet fever.2 It is an essential cause of acute kidney injury ensuing from immune-mediated tubulo-interstitial injury, instigated by drugs, infections or systemic illnesses.

Of all the aetiologies recognised, the most frequent cause of ATIN is drug-induced and is thought to underlie 60–70% of all cases of AINs.3 Drugs are increasingly implicated as aetiological factors in ATIN because of their increased usage worldwide, increased recognition of characteristic features of ATIN and diagnostic confirmation on renal biopsy. Drug classes commonly associated with ATIN include the antibiotics (cephalosporins, penicillins, rifampicin, sulphonamides, vancomycin and rarely flouroquinolones), NSAIDs (almost all), diuretics and other widely prescribed drugs like proton pump inhibitors. Development of drug-induced ATIN is not dose-related, whereas analgesic nephropathy is cumulative dose-dependent.

NSAIDS are notorious in causing a variety of acute and chronic kidney injury syndromes. These syndromes may occur in the form of fluid and electrolyte disturbances, prerenal azotaemia, acute kidney injury, nephrotic syndrome and ATIN. The NSAID-induced ATIN is likely to be an immunological delayed hypersensitivity response, unlike others which are attributable primarily to prostaglandin inhibition. In contrast with other causes of ATIN that typically present with mild proteinuria, NSAID-induced ATIN may present with nephrotic syndrome. Although drug-induced ATIN usually improves after discontinuation of the offending medication, with or without steroids, NSAID-induced ATIN is more likely to cause permanent renal injury as compared with other drugs causing ATIN. In our patient we strongly feel that the causative agent of ATIN was aceclofenac, although the patient was simultaneously on losartan and metformin. First, because the aceclofenac was a new introduction into the drug regime and subsequent to its withdrawal the kidney recovered. Second she was on losartan and metformin for a pretty long time earlier and had never suffered any renal damage in the past. However, having said so, we cannot conclude that there was no potential conflict or interaction of aceclofenac, metformin and losartan that led to the acute worsening of renal functions.

The clinical presentation of ATIN is typically non-specific as was evident in our case. The classical triad of fever, skin rash and peripheral eosinophilia is present in a minority of patients. The renal function deteriorates rapidly, as measured by elevated creatine and blood urea nitrogen. Patients are usually non-oliguric to start with. The immunological pathogenesis is evident on the renal biopsy documenting the presence of helper-inducer and suppressor-cytotoxic T lymphocytes complement proteins, immunoglobulins and anti-tubular basement membrane antibodies in the inflammatory infiltrate of the renal interstitium.

The most important issues in ATIN patient management is withdrawal of the offending medication, substituting it with safer alternatives and correction of electrolyte abnormalities. Decision to use steroids should be guided by the clinical course following withdrawal of offending medications.4 Small studies have demonstrated rapid diuresis, clinical improvement and return of normal renal function within 72 h after starting steroid treatment, although some indicate lack of efficacy, especially in cases of NSAID-induced ATIN.5 Recently a large multicentric retrospective study was carried out to determine the influence of steroids in patients of biopsy-proven drug-induced ATIN.6 The authors recommended that steroids should be started promptly (within 7 days after diagnosis) to avoid subsequent interstitial fibrosis and an incomplete recovery of renal function.6 Delayed steroid treatment has less pronounced therapeutic benefit.7 The dose of prednisone is 1 mg/kg/day orally for 2–3 weeks, followed by a gradually tapering dose over 3–4 weeks.8 Immunosuppressants and cytotoxics like cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil have no role in the management of ATIN. Overall prognosis of drug-induced ATIN is favourable and at least partial recovery of kidney function is normally observed.9

Learning points.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely consumed drugs, and with their increasing usage worldwide, NSAID-induced AIN is likely to become more frequent.

Most patients with acute tubulointerstitial nephritis recover normal or near-normal renal function in a few weeks of withdrawing the offending medications.

Awareness and periodic monitoring of renal functions in patients on NSAIDs might facilitate more rapid diagnosis and aid in management of this potentially reversible condition.

Footnotes

Contributors: MG and SDC have seen and managed the case and have drafted the initial version of this manuscript. RN and PA have helped us with the histopathology of the renal biopsy and radiological guidance for renal biopsy respectively and have provided valuable inputs into patient case management. All the authors have critically analysed the text, images and contributed significantly in shaping the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kodner CM, Kudrimoti A. Diagnosis and management of acute interstitial nephritis. Am Fam Physician 2003;2013:2527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Councilman WT. Acute interstitial nephritis. J Exp Med 1898;2013:393–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatzikyrkou C, Hamwi I, Clajus C, et al. Biopsy proven acute interstitial nephritis after treatment with moxifloxacin. BMC Nephrol 2010;2013:11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eknoyan G, Raghvan R. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. In: Schrier RW, Coffman TM, Falk RJ, Molitoris BA, Neilson EG, eds. Schrier diseases of the kidney. 9th edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013:994–1013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pusey CD, Saltissi D, Bloodworth L, et al. Drug associated acute interstitial nephritis: clinical and pathological features and the response to high dose steroid therapy. Q J Med 1983;2013:194–211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González E, Gutiérrez E, Galeano C, et al. Early steroid treatment improves the recovery of renal function in patients with drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int 2008;2013:940–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Praga M, González E. Acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int 2010;2013:956–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aradhye S, Neilson EG. Treatment of acute interstitial nephritis. In: Brady HR, Wilcox CS, eds. Therapy in nephrology and hypertension. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 1999:232–5 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010;2013:461–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]