Abstract

Function of a renal allograft relies on the integrity of its vascular anatomy. Renal biochemistry, ultrasound and percutaneous biopsy are used in combination to determine allograft function. Biopsy is not without risk, and in this case study we demonstrate a rare but a potentially life-threatening complication of renal allograft biopsy.

Background

A total of 1009 living donor kidney transplants were carried out between the period of 1 April 2011 and 31 March 2012 in the UK .1 Core biopsy remains the ‘gold-standard’ for the diagnosis of allogenic transplant dysfunction.2 Bleeding is a recognised risk of this procedure, and this case demonstrates how ultrasound can be a useful and specific test in detecting such a complication.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old obese man with a background of familial polycystic kidney disease had been receiving haemodialysis for an 8-month period. He went on to have an elective primary live donor renal transplant from his cousin. His baseline renal function was a urea of 21.9 mmol/l and a creatine of 721 µmol/l. The operation went smoothly, and there was clear evidence of urine production intraoperatively. A J–J stent and an implantable Doppler device were left in situ.

Postoperatively his renal function improved, and by day 5 his creatine had fallen to 160 µmol/l. His coagulation parameters remained within normal limits throughout.

To rule out allograft dysfunction, ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal biopsy was carried out 8 days after surgery. The procedure was conducted without any difficulty, and the patient was instructed to rest in bed following it. Over the next 3 h period he developed gradually worsening right iliac fossa pain, and eventually guarding over the site of the transplant. His respiratory rate rose to 24, but his pulse remained stable at 74 beats per minute, with a blood pressure of 135/70 mm Hg. Intravenous morphine was unable to control his pain.

Investigations

Approximately 3 h after the development of his pain, an urgent portable ultrasound of the transplanted kidney was requested. A Toshiba VIAMO portable ultrasound machine was used to scan the patient. Given the average performance of a basic standard portable machine and the patient's large body habitus, the examination was technically challenging. Standard B-mode ultrasound images revealed a haematoma adjacent to the interpolar of the transplant kidney in the first instance (figure 1). Interestingly, after the application of colour Doppler, a jet of high-velocity flow was seen travelling through the renal cortex and out into the centre of the haematoma (figure 2). The patient went for an urgent CT angiogram, which confirmed that the jet of flow seen on the Doppler was undoubtedly an active extravasation from an upper pole vessel into a now very large perinephric haematoma (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Haematoma adjacent to the interpolar of the kidney.

Figure 2.

High-velocity flow travelling through the renal cortex and out into the centre of the haematoma.

Figure 3.

Active extravasation from an upper pole vessel into a large perinephric haematoma.

Differential diagnosis

On B-mode ultrasound, the initial appearances of the perinephric collection could have represented resolving postoperative haematoma, or an infected perinephric collection.

Treatment

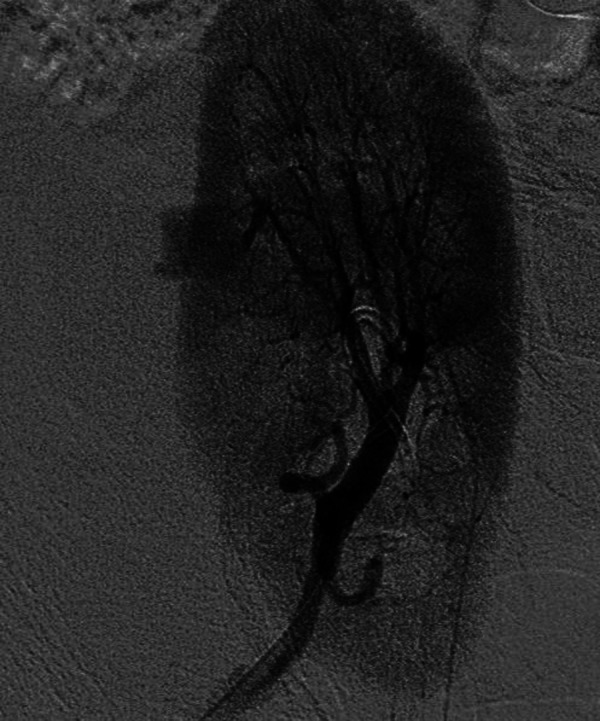

After a transfusion of two units, the patient was transferred to the angiography suite. A right-sided common femoral artery puncture was made under ultrasound guidance. A five French sheath was sited and a four French bolia catheter were negotiated into the transplant artery. An upper pole branch was identified as the bleeding vessel (figure 4) and two 2 mm×2 cm AZUR coils were deployed to good effect (figure 5).

Figure 4.

Bleeding upper pole vessel.

Figure 5.

Two 2 mm×2 cm AZUR coils deployed with good haemostasis.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient recovered swiftly following embolisation and transfusion. His haemoglobin levels rose to 11.8 g/dl and his recorded urine output was 1.4 litres during a 24 h period post-treatment. A surveillance ultrasound scan excluded any complications such as hydronephrosis, and the patient was discharged 7 days after embolisation.

The biopsy showed features of acute tubular injury, moderate to severe donor vascular disease and marked arteriolar sclerosis.

Discussion

Percutaneous biopsy of transplanted kidneys is commonplace in many centres, and despite the associated risks it remains an important test. It yields definitive information about acute and chronic graft rejection, the nature of the treatment and on the prognosis of the transplant.3 4 The information derived from renal biopsy changes patient care in up to 40% of cases.5

Percutaneous renal biopsy can be performed under real-time ultrasound guidance or blindly. There is an increasing tendency to use ultrasound due to its lower complication rate.6 Bleeding is often the prime concern after the procedure, and can occur any time within the first 24 h following a biopsy.4 We stress that active bleeding detected on portable ultrasound is an extremely rare finding. Haemorrhage can occur in either the collecting system, under the renal capsule, within the perinephric space, or due to puncture of a major renal vessel. Other potential complications of biopsy include arteriovenous fistulas, perirenal soft tissue infection and rarely puncture of abdominal viscera.

If portable ultrasound is readily accessible, it can be a very useful test in suspected postbiopsy complications. Potential findings may include perinephric collections, hydronephrosis or Doppler abnormalities. However, demonstrating active extravasation on colour flow Doppler is unusual, and to our knowledge this is the only published case of such an observation in a postbiopsy transplant kidney. It is important to reiterate that if ultrasound is not readily accessible, it should not delay referral for an urgent CT angiogram, which is a more sensitive and specific test in this scenario.

Learning points.

Risk of haemorrhage after percutaneous renal biopsy should not be overlooked.

Ultrasound Doppler is a useful first-line test in this situation, and active haemorrhage is a rare but potential finding.

Selective angiographic intervention is minimally invasive and can potentially salvage a threatened transplant kidney.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr R Miles, Consultant Interventional Radiologist, and the Derriford Hospital Interventional Radiology Team.

Footnotes

Contributors: JR conceptualised the idea and edited the images. JR, CP, PD drafted the manuscript. RH and CG all commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.NHS Blood and Transplant Organ Donation Statistics. Last updated July 2012 http://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/ukt/statistics/ (accessed 1 Nov 2012).

- 2.Ahmad I. Biopsy of the transplant kidney. Semin Intervent Radiol 2004;2013:275–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams WW, Taheri D, Tolkoff-Rubin N, et al. Clinical role of the renal transplant biopsy. Nature reviews. Nephrology 2012;2013:110–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittier WL, Korbet SM. Timing of complications in percutaneous renal biopsy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;2013:142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards NT, Darby S, Howie AJ. Knowledge of renal biopsy alters patient management in over 40% of cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994;2013:1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maya ID, Maddela P, Barker J, et al. Percutaneous renal biopsy: comparison of blind and real-time ultrasound guided technique. Semin Dial 2007;2013:355–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]