Abstract

Laryngeal leiomyosarcoma is an exceedingly rare malignant tumour, with fewer than 50 reported cases in scientific literature. Diagnosis is based on immunohistochemistry, supplemented with ultrastructural studies, if required. It is aggressive and associated with variable survival outcomes. A 63-year-old man presented with hoarseness for 7 months and breathlessness for 3 months. Imaging showed a well-defined 3 cm glottic mass. Total laryngectomy was performed. The histopathological examination showed features of leiomyosarcoma. The index case has been presented owing to its rarity, variable clinical manifestations and diagnostic dilemmas and to stress upon the importance of ancillary techniques for confirmation.

Background

Laryngeal mesenchymal tumour in itself is a rarity (<1%), out of which leiomyosarcoma is one of the most uncommon types, accounting for less than 0.1%.1 It was only in 1939 that the first description of laryngeal leiomyosarcoma (LMS) was given by Jackson and Jackson.2 It poses a challenge, not only for the clinicians and radiologists because of its close mimicker—laryngeal carcinoma, but also for the pathologists to differentiate it from other mesenchymal tuomours as well as sarcomatoid carcinomas, which makes ancilliary techniques like immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy a necessary armamentarium. An accurate diagnosis is warranted for appropriate management options and for prognostication.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old man presented to department of otorhinolaryngology in February 2012 with hoarseness for 7 months and breathlessness for 3 months; the latter progressed to stridor, necessitating an emergency tracheostomy. He also had progressive dysphagia for solids for 4 months along with a foreign body sensation in throat. The person has a history of smoking for 30 years with an average of 10 cigarettes/day, but is non-alcoholic.

Investigations

Fiberoptic examination revealed a rounded, 3 cm mass with smooth surface, at the level of the glottis. Supraglottis was free. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy. Contrast enhanced CT and MRI of the neck (figures 1 and 2) showed a well-defined 3 cm glottic mass, arising from right true cord. Direct laryngoscopy confirmed a firm, submucosal lesion on the right vocal cord extending across the anterior commissure and onto the anterior one-third of the left vocal cord.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced MRI neck—axial cut showing a well-defined soft tissue density of the right-sided glottic larynx with no bony erosion or extra laryngeal spread.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced MRI neck—coronal cut showing a well-defined soft tissue density of the right-sided glottic larynx with no bony erosion or extra laryngeal spread.

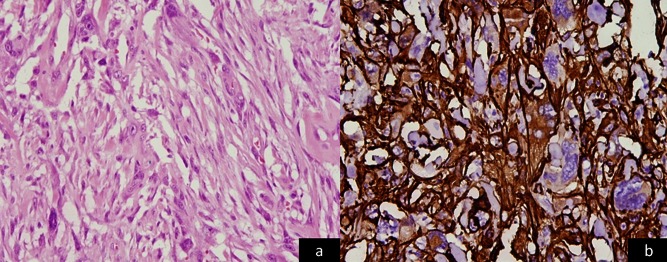

Thereafter the patient underwent direct laryngoscopic biopsy, revealing a malignant mesenchymal tumour and laryngectomy performed. Gross examination of the specimen showed a greyish white unencapsulated polypoidal tumour measuring 4×2.5×2 cm arising from the right cord and the anterior commissure. No cartilage involvement was noted. The microscopic examination (figure 3A) showed a mesenchymal tumour composed of intersecting fascicles of spindle cells with moderate to marked pleomorphism, presence of tumour giant cells and brisk mitosis. On the basis of above histomorphology, differential diagnosis considered were sarcomatoid carcinoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Neoplastic cells were diffusely immunopositive for smooth muscle actin (figure 3B) while immunonegative for desmin, myogenin, pancytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD34 and S-100. Thus final diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma was performed.

Figure 3.

(A): Microphotograph shows a malignant mesenchymal tumour with interlacing fascicles of spindle cells showing marked nuclear pleomorphism, tumour giant cells and high mitotic activity (H&E ×200). (B) Immunohistochemistry shows neoplastic cells positive for smooth muscle actin (IHC SMA, ×200).

Differential diagnosis

Sarcomatoid carcinoma

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour

Leiomyosarcoma

Angiosarcoma

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma

Treatment

Total laryngectomy

Radiotherapy

Outcome and follow-up

There is no evidence of loco-regional recurrence or distant metastasis during a total follow-up of 6 months.

Discussion

Laryngeal malignancies account for 1–5% of total malignancies, the majority being squamous cell carcinomas. Mesenchymal tumours comprise a very insignificant proportion of laryngeal malignancies, accounting for roughly 1%, the majority being undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas.3

Leiomyosarcomas of head and neck are uncommon, and among them location of a leiomyosarcoma in the larynx is still very infrequent. Glottis and supraglottis represent 87% of these.4 Jackson et al in 1939 were the first to report such a case. The rarity of this tumour can be judged by the fact that since then only around 40 other cases have been published and no series with more than two cases.

LMSs are most commonly encountered in the fifth decade of life, although it may appear at any age, even in childhood5, the ratio of male to female being 4:1. Poor establishment of any valid pattern for its presentation is attributed to the low number of cases reflected in the literature so far.

There is no relation between smoking or alcohol intake and the onset of this tumour.6 There are various theories regarding the origin of head and neck leiomyosarcomas. Freiji et al7 hypothesised blood vessel smooth muscle to be a possible site of origin, whereas Chen et al8 attributed the origin to aberrant mesenchymal differentiation.

The diagnosis of this tumour is histological and implies the need for immunohistochemical tests and even electron microscopy, if required. The other histological variables which can be confused with this entity include spindle-shaped cell tumours of larynx: sarcomatoid carcinoma, melanoma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, nodular fascitis, neurogenic tumour, fibrohistiocytic tumour and vasoformative tumours. The sarcomatoid carcinomas are generally accompanied by the carcinomatous component and show diffuse immuno-positivity for pancytokeratin. The pleomorphic sarcomas can be differentiated by immunohistochemical analysis. Angiosarcomas, neurogenic tumours and fibro-histiocytic tumours show positivity for CD34, S-100 and CD68, respectively. Spindle cell melanomas are immuno-positive for Human Melanoma Black (HMB)-45 and S-100. Nodular fasciitis shows a characteristic zonation effect and loose arrangement of cells in tissue culture like manner, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour is relatively circumscribed and contains spindle cell proliferation in a background of fibrosis with lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, foamy macrophages and occasionally eosinophils and neutrophils.

The treatment modality of choice for LMS is surgery. Surgical modalities vary considerably according to site and extent of lesion. It may range from conservative procedures, like microlaryngeal surgery, laser debulking, vertical partial laryngectomy and simple partial laryngectomy, to more aggressive procedures, such as total laryngectomy. However, conservative surgeries have high recurrence rates and thus are generally not recommended. Experience with uterine leiomyosarcoma, which is the most frequent location, proves the high rate of local recurrence along with chances of remote metastases in 50% of patients; the most frequent sites being the lung, brain and spine. This metastasis may appear even years after the initial treatment. Eeles et al9 studied 103 cases of head and neck sarcomas, in which they found a 5-year survival rate, 5-year local recurrence free survival and 5-year metastasis free survival of 45%, 39% and 60%, respectively. Owing to rarity of LMS, a specific mention of its recurrence and metastasis is not available in present literature. Noting the fact that the tumour has haematogenous dissemination, less than 10–15% of patients may have cervical lymph node involvement, thus limiting the role of elective cervical dissection.10 Primary chemotherapy has been used in a small number of uterine cases, with 20–50% response and less than 1 year survival. No significant response has been seen with isolated radiation therapy on its own, whether for the primary tumour or for metastases.11

Learning points.

Any case presenting with dyspnoea, dysphagia or hoarseness owing to laryngeal mass should be evaluated in detail by the primary care physician, including direct laryngoscopic examination, followed by a histo-pathological confirmation of the lesion.

The clinical presentation and imaging finding may be non-specific, and the final say in establishing the diagnosis of a laryngeal mass is exclusively histological.

Surgical resection with negative margins seems to be the therapeutic option that optimises the long-term prognosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS provided clinical details; LS and SM contributed to manuscript preparation and RS was in charge of the case.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Thompson LDR, Fanburg-Smith JC. Tumours of the hypopharynx, larynx and trachea. In: Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Editors: Leon Barnes, John W. Eveson, Peter Reichart, David Sidransky. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005:148, . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson C, Jackson CL. Sarcoma of the larynx. In: Jackson C, ed. Cancer of the larynx. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1939:167–8 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadhwa AK, Gallivan H, O'Hara BJ, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx: diagnosis aided by advances in immunohistochemical staining. Ear Nose Throat J 2000;2013:42–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez J, Muntané MJ, Del Prado M, et al. Leiomiosarcoma laríngeo. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2001;2013:254–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chizh I, Ogorodnikova LS, Birina LM, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx in an 8-year-old girl. Vestn Otorinolaryngol 1976;2013:104–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lippert BM, Schlütter E, Claasen H, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1997;2013:66–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freiji JE, Gluckman JL, Biddinger PW, et al. Muscle tumors in the parapharyngeal space. Head Neck 1992;2013:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JM, Novick WH, Logan CA. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx. J Otolaryngol 1991;2013:345–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eeles RA, Fisher C, A'Hern RP, et al. Head and neck sarcomas: prognostic factors and implications for treatment. Br J Cancer 1993;2013:201–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas S, McGuff HS, Otto RA. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx. Case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1999;2013:794–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cocks H, Quraishi M, Morgan D, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;2013:643–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]