Abstract

We report the case of a patient with a palpable mass and abdominal pain in the left upper quadrant. A physical examination revealed tenderness in this region. An ultrasound performed initially showed a large cystic structure. A CT examination revealed a large cyst originating in the spleen with loculations in its upper part and focal calcification in the wall. On MRI, the cystic mass showed high signal on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images. The carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) was measured at 88 U/ml (standard <37.1 mUI/l). According to the imaging examinations and laboratory tests performed, it was impossible to determine if the splenic cyst was parasitic or non-parasitic. Given the most important risks of complications encountered in parasitic cysts, it was decided to treat this splenic cyst as a parasitic cyst. For this reason, an elective laparoscopic splenectomy with preoperative embolisation of the splenic artery was performed. The histological diagnosis was a primary epidermoid splenic cyst with inner lining epithelial cells.

Background

Splenic cysts are rare; they are classified as primary or secondary based on the lack of lined epithelium. Primary cysts are categorised as parasitic (Echinococcus infection) and non-parasitic. Among primary cysts, it is important to distinguish between parasitic and non-parasitic cysts because the therapeutic approach is different. Several diagnostic tools are available such as imaging, serological tests, clinical data and patient's history. It can be, however, challenging to distinguish between the two entities, especially when imaging and anamnesis are in favour of a parasitic origin but serological tests are negative (as in our case). The purpose of this paper is to discuss the various diagnostic tools to differentiate parasitic and non-parasitic cysts. Therapeutic options are also discussed.

Case presentation

An 18-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department with an acute abdominal pain, and reported also intermittent pain in the left shoulder for about 1 year. Physical examination revealed tenderness in the left upper quadrant, and a palpable spleen. She also mentioned multiple trips to Africa 8 years ago. Otherwise, her medical history was negative.

Investigations

The serological tests were negative for Echinococcus (granulosis and multilocularis) and helminthic infection. The carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) was measured at 88 U/ml (standard <37.1 mUI/l). The abdominal ultrasound (US) performed at the emergency department showed a giant cystic mass in the left upper quadrant. A CT of the abdomen (figure 1) revealed a large cystic structure with a diameter of 20 cm originating in the spleen, displacing the pancreas and stomach on the right side. The upper portion of the cyst presented a multilocular appearance. Discrete calcifications were also noted in the cyst wall. The cyst content was measured at 30 HU. The other abdominal organs were normal.

Figure 1.

A CT of the abdomen showing a huge splenic cyst with multilocular appearance in its upper part (A), containing calcification (B). The coronal view demonstrates an important displacement of the pancreas and stomach (C).

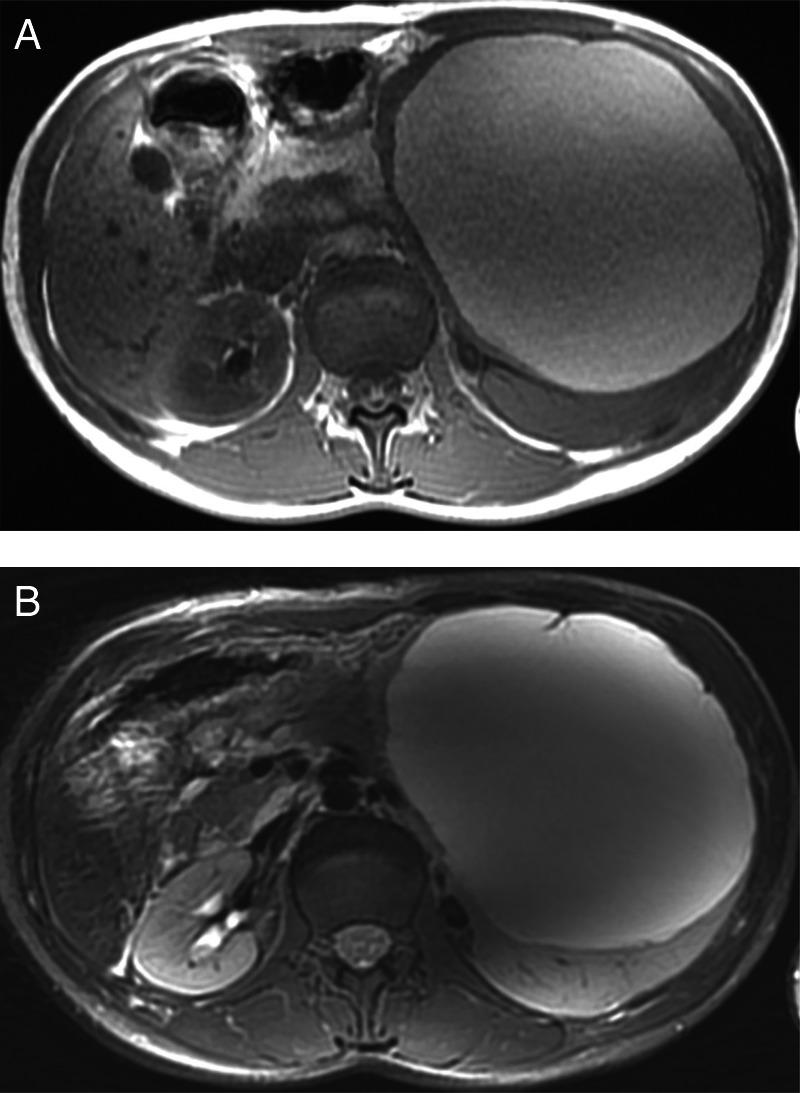

On MRI (figure 2), performed with a GE Discovery MR750 3.0T using LAVA sequences, diffusion, T1-weighted and T2-weighted images, the cystic mass showed high-signal intensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images. Within the cyst, thin septations and calcifications were noted. No enhancement in the cyst wall and no signal on diffusion were seen.

Figure 2.

MRI showing the cystic mass with high-signal intensity on T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) images.

Differential diagnosis

In our case, the differential diagnosis is mainly between a parasitic and a non-parasitic splenic cyst. The distinction between these two lesions is essential because the treatment is completely different.

Treatment

The patient was hospitalised for 3 days with a diagnosis of a huge splenic cyst of unknown origin. According to the imaging examinations and laboratory tests performed, it was impossible to determine if the splenic cyst was parasitic or non-parasitic. Given the most important risks of complications encountered in parasitic cysts, it was decided to treat this splenic cyst as a parasitic cyst. For this reason, a treatment with albendazole was introduced for a period of 4 weeks, and the patient had a prophylactic vaccination (against Haemophilus influenzae, Meningococcus and Pneumococcus) before total splenectomy.

An elective laparoscopic splenectomy with preoperative embolisation was considered.

Six weeks later, a preoperative splenic embolisation was performed, with placement of coils in the upper and lower branches of the splenic artery and at their junction sparing the pancreatic arteries. The postembolisation angiographic control was satisfactory with an almost complete devascularisation of the spleen (figure 3).

Figure 3.

An angiogram showing the splenic artery before and after embolisation, with placement of coils in the upper and lower branches.

Exploratory laparoscopy revealed a voluminous spleen containing a large cyst. The procedure was initiated with the puncture of the cyst and evacuation of a brown liquid, reducing significantly the cyst size, after which 100 ml of 94% alcohol was instilled into the cyst. Finally, total laparoscopic splenectomy was performed. During the procedure, arteriel bleeding in the splenic hilum was controlled with a clip. No postoperative complications were mentioned. The postoperative course was uneventful. A cytological examination of the aspirated fluid revealed blood, few histiocytes and absence of scolices.

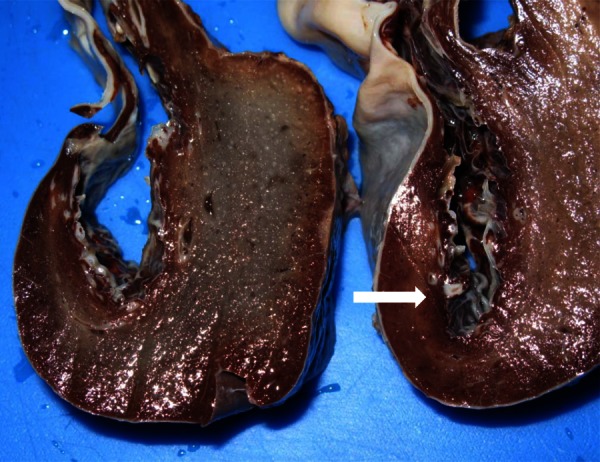

On pathological examination (figure 4), the spleen measured 19×15 cm, with an 18 cm diameter cyst. Splenic tissue inclusions were found focally in the cystic wall. On microscopic examination (figure 5), the cystic lesion was delimited by a fibrous capsule with a focally keratinised squamous epithelium. These histological findings were compatible with an epidermoid cyst.

Figure 4.

On macroscopic examination (cut section), the internal cyst wall demonstrates white coarse fibrous trabeculations (white arrow).

Figure 5.

The microscopic examination showing a keratinised squamous epithelium lining the inner cystic wall (A and B).

Outcome and follow-up

No postoperative complications were mentioned. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Discussion

According to Fowler1 (table 1), splenic cysts are classified into two categories: primary (true) and secondary cysts (false). Only primary cysts contain epithelial lining. Secondary cysts are related to trauma and splenic infarction, often due to haematological disorders. These cysts are composed of fibrous tissues with no epithelial lining. Among true cysts, the most common are parasitic cysts (caused by Echinococcus); other aetiologies include congenital and neoplastic cysts.

Table 1.

Classification of splenic cysts

| Primary cysts (true) | Secondary cysts (false) |

|---|---|

| Parasitic | Post-traumatic |

| Echinococcus | Splenic infarct |

| Non-parasitic | |

| Congenital | |

| Neoplastic | |

| Lymphoma | |

| Metastase |

Epidermoid cysts are considered as primary cysts and are classified as congenital. Their origin is not clear; it has been proposed that during embryogenesis, splenic cysts are formed by infolding or inclusions of peritoneal mesothelial cells in the splenic parenchyma.2

In this case, the main challenge was to differentiate a non-parasitic cyst from a parasitic cyst, because anamnesis and imaging were in favour of parasitic origin, while the clinical presentation was aspecific, and the serological results for Echinococcus were negative.

Symptoms of splenic cysts are non-specific. Patients with small-sized cyst are usually asymptomatic. Symptoms appear when the cyst reaches a considerable size, sometimes after a minor trauma, which leads to an intracystic haemorrhage. Abdominal mass and pain are usually reported by patients. Pain varies in distribution, but is generally described in the left upper quadrant. A postprandial discomfort and a dull ache are related to compression of the stomach. Rarely, urinary symptoms with the left flank pain are because of compression on the renal pelvis or left ureter. Dyspnoea, respiratory infections, tachycardia are also been described secondary to compression on thoracic viscera.3

At macroscopic examination, the classical non-parasitic cyst of the spleen such as an epidermoid cyst, shows a white or greyish-white, smooth internal wall with coarse fibrous trabeculations. At microscopic examination, the lining epithelium is of various natures such as epidermoid epithelium, transitional epithelium and mesothelium.

The cyst content can be either thin and serous or viscous and turbid. The colour may vary from yellow to brown. The cholesterol crystals, macrophages or degradation product of haemoglobin can be found within the cyst.2

On imaging examinations, epidermoid and hydatid splenic cysts may have a similar appearance. On US, a well-defined, solitary cystic lesion with septations may be recognised. At CT, both the lesions may present calcifications, internal debris and no enhancement. On MRI, splenic cysts have a high signal on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images. The T1 signal intensity may vary according to the cysts content, an increased signal intensity indicate the presence of cholesterol, proteins or blood products.4 5

Findings such as daughter cysts or coexisting cysts in liver are in favour of parasitic cysts.6 Classic epidermoid splenic cysts usually have a non-calcified thin wall. In 10% of those cases, calcifications have been shown.5

The CA 19-9 is an aspecific antigen. Elevated blood levels are seen in the epidermoid splenic cyst and in malignant conditions such as pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer and gastric cancer. An elevated concentration has also been described in benign diseases such as cystic fibrosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.2 7 In an epidermoid splenic cyst, the concentration of CA 19-9 is also elevated, owing to the production by the squamous epithelium.8 Thus, CA 19-9 cannot be used as a single tool to diagnose an epidermoid cyst of the spleen.

The presence of Echinococcus infection can be evaluated by serological tests. Among these tests, the ELISA with an average sensitivity around 80% and a specificity ranging from 95% to 100% is the best overall choice.9 10 However, a negative test does not exclude the disease. False-negative tests are encountered when cysts are calcified, corresponding to a lack of antigenic stimulation.11 A false-positive result may be seen in other infections like helminthic diseases.10 It is important to be aware that response to hydatid antigen depends on multiple factors such antigen quality, organ site, number of hydatid cysts and individual variability of immune response.10 12

A positive serological test has always to be correlated with clinical history and imaging findings to confirm the diagnosis of Echinococcus.10

Generally, surgical treatment of splenic cyst is recommended for symptomatic patients and for cysts larger than 5 cm. The goal of the surgical procedure is to avoid complications and prevent recurrence.13

Classically, the treatment for hydatid and epidermoid splenic cyst was total splenectomy; but, since 1970–1980, owing to the important role of the spleen in the immunological function, the trend was to a more conservative approach. After total splenectomy, there was a higher risk of developing an overwhelming postsplenectomy infection.2 14

Several conservative procedures are available for the treatment of epidermoid splenic cysts, the indications of which depend on location and cyst size.

Partial splenectomy was indicated when the cyst is located at the pole, or in a deep location, with conservation of more than 25% of the splenic parenchyma.14

Marsupialisation is recommended for superficial splenic cysts, this method reduces the duration of operation, but presents with a high rate of recurrence.2 15

Fenestration of the superficially located cysts has been described.14

As in our case, a conservative approach was impossible. A large cyst was located near the splenic hilum and surrounded by splenic tissue, thus a total splenectomy was indicated.15

The hydatid cyst of the spleen can also be treated with conservative surgical procedures. Puncture, aspiration, injection and reaspiration (PAIR) was introduced in 1986 for the treatment of cysts in liver, spleen, kidney and abdominal cavity. PAIR includes the following steps: percutaneous puncture of cysts under US guidance, aspiration of the cyst content, injection of protoscolicidal substances (95% ethanol or 20% sodium chloride solution) for about 15 min and finally reaspiration of the fluid cyst content.10 16 This method was indicated for inoperable patients and presents less complications than surgery. The risks include those usually encountered in puncture (such as haemorrhage, mechanical damage of the tissues and infections). There is also a risk of infectious material spillage in the peritoneal cavity with dissemination of the disease, which can lead to secondary anaphylactic shock.10 16 17 Unroofing the cyst wall with omentoplasty was indicated for superficial cyst. In this technique, the cyst was removed after unroofing of the cyst wall, leaving behind a pericystic layer and a residual cavity which carries the risk of postoperative infection.17 18

For all these reasons, total splenectomy remains the therapeutic procedure of choice for the hydatid splenic cyst, because of the low mortality and morbidity rate, and offers a complete cure of disease.17 18

In our case, a preoperative embolisation of splenic artery was performed before the laparoscopic splenectomy to reduce intraoperative blood loss, splenic size and to minimise the risk of conversion to an open splenectomy.19

It is therefore crucial to know the exact nature of the cyst prior to any surgical treatment to avoid complications related to misdiagnosis. Thus, when differentiation between a parasitic and a non-parasitic splenic cyst is not possible by imaging methods and serology (as in our case), it should be considered and treated as parasitic infection.20

Learning points.

Epidermoid cysts are rare, parasitic cyst must always be included in the differential diagnosis.

Imaging of parasitic and non-parasitic cysts may be similar and represents a diagnostic challenge.

When differentiation between parasitic and non-parasitic cysts is difficult or impossible, the cyst should be considered and treated as parasitic.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributors: QDV was the editor of the manuscript, diagnostic of the case and contributed to data collection. EM and HMH were the supervisor and corrector.

References

- 1.Fowler RH. Cystic tumours of the spleen. Int Abstr Surg 1953;2013:209–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgenstern L. Non-parasitic splenic cysts. J Am Coll Surg 2002;2013:306–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qureshi MA, Hafner CD. Clinical manifestations of splenic cysts study of 75 cases. Am Surg 1965;2013:605–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabushka LS, Kawashima A, Fishman EK. Imaging of the spleen: CT with supplemental MR examination. Radiographics 1994;2013:307–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson A, Frush DP, Donnelly LF, et al. A pattern-oriented approach to splenic imaging in infants and children. Radiographics 1999;2013:1465–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson F, Leander P, Ekberg O. Radiology of the spleen. Eur Radiol 2001;2013:80–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HR, Lee CH, Kim YW, et al. Increased CA 19-9 level in patients without malignant disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 2009;2013:750–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higaki K, Jimi A, Watanabe J, et al. Epidermoid cyst of the spleen with CA 19-9 or carcino-embryonic antigen productions. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;2013:704–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig PS, Rogan MT, Campos-Ponce M. Echinococcosis: disease, detection and transmission. Parasitology 2003;2013(Suppl):S5–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO)/Office International Des Epizooties (OIE) WHO/OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. In: Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin F-X, Pawlowski ZS, eds. OIE. Paris, France: World Organisation for Animal Health. 2001:1–265 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biava MF, Dao A, Fortier B. Laboratory diagnosis of cystic hydatic disease. World J Surg 2001;2013:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sbihi Y, Rmiqui A, Rodriguez-Cabezas MN, et al. Comparative sensitivity of six serological tests and diagnostic value of ELISA using purified antigen in hydatidosis. J Clin Lab Anal 2001;2013:14–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gianom D, Wildisen A, Hotz T, et al. Open and laparoscopic treatment of non-parasitic splenic cysts. Dig Surg 2003;2013:74–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen MB, Moller AC. Splenic cysts. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2004;2013:316–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macheras A, Misiakos EP, Liakakos T, et al. Non-parasitic splenic cysts: a report of three cases. World J Gastroenterol 2005;2013:6884–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ 1996;2013:231–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meimarakis G, Grigolia G, Loehe F, et al. Surgical management of splenic echinococcal disease. Eur J Med Res 2009;2013:165–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safioleas M, Misiakos E, Manti C. Surgical treatment for splenic hydatidosis. World J Surg 1997;2013:374–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z, Zhou J, Pankaj P, et al. Comparative treatment and literature review for laparoscopic splenectomy alone versus preoperative splenic artery embolization splenectomy. Surg Endosc 2012;2013:2758–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adas G, Karatepe O, Altiok M, et al. Diagnostic problems with parasitic and non-parasitic splenic cysts. BMC Surg 2009;2013:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]