Abstract

The case report illustrates an acute myocardial infarction (MI) in a 41-year-old hypertensive woman possibly because of an intake of a combination of tranexamic acid and mefenamic acid for dysmenorrhoea and menorrhagia. There are multiple case reports of MI occurring in the setting of the use of antifibrinolytic agents including tranexamic acid. The present case serves as a warning that, even in patients with an apparently low risk for arterial thrombosis, these drugs may be implicated as a precipitant of MI.

Background

Antifibrinolytic agents including tranexamic acid have an important therapeutic role in controlling bleeding in patients with congenital and acquired bleeding disorders. They are being increasingly used in patients with blood loss and to prevent bleeding. However, these antifibrinolytic agents can also facilitate the development of thrombosis. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are very widely prescribed by general practitioners and there are reports in literature regarding adverse cardiovascular events with their use. We report a case of acute myocardial infarction (MI) in a 41-year-old hypertensive woman following the intake of a combination of tranexamic acid and mefanamic acid.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old female patient, a known hypertensive for the last 6 years on a combination of amlodipine 5 mg+atenolol 50 mg once daily presented to casualty with retrosternal squeezing type of chest pain with radiation to left arm and associated with sweating. She reported to our casualty 4 h and 15 min after the onset of chest pain.

She had a history of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhoea for the past 3 years. She was evaluated for the same and found to have a fibroid in her uterus. She was put on a combination of tranexamic acid 500 mg and mefenamic acid 250 mg three times a day. She had been taking this for the last 2 years, every 5 days from the onset of every menstrual period. The last time she had consumed the drug was 14 days prior to the onset of chest pain.

There was no other significant history.

She was a mother of two children and her last child birth was 13 years back. Her antenatal and postnatal periods were uneventful. She had no history of miscarriages

She was a non-smoker and non-alcoholic, and had no history of any recreational drug use.

Her mother, father and four siblings had no significant history. At admission, on examination her pulse rate was 64/min regular, BP was 170/90 mm Hg and her jugular venous pressure was not elevated. She was pale. Her cardiovascular examination was normal except for an LV S4. Her general examination and other systemic examinations were within normal limits.

The resting 12-lead ECG showed ST elevation MI (inferior wall+right ventricle MI). Her ECHO revealed a dilated left ventricular (LV) (5.42/3.15 cm) with concentric LV hypertrophy and good LV systolic function (ejection fraction 63.9%), regional wall motion abnormality right coronary artery (RCA) territory, Stage 1 diastolic dysfunction.

She was taken for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and the coronary angiography, which showed a discrete eccentric 99% lesion of proximal RCA with thrombus with thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction (TIMI) 1 flow distally. Thrombus aspiration was performed with a Thrombuster II device and the lesion was stented with 4×15 Prolink (BMS). TIMI III flow attained (door to balloon time was 45 min) (figures 1–4)

Figure 1.

Right coronary angiogram showing total block on the artery proximally.

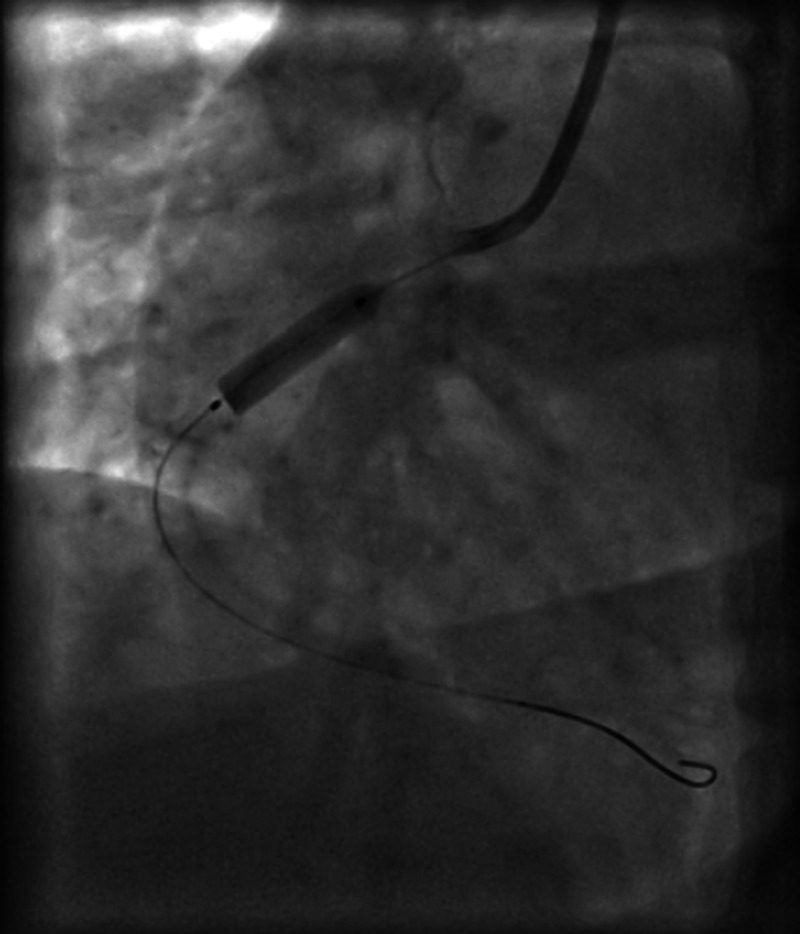

Figure 2.

Opening up of the right coronary artery on passing a wire.

Figure 3.

Balloon dilation of the right coronary artery and stenting.

Figure 4.

Normal TIMI 3 flow restored in the above patient.

Investigations

Investigations showed haemoglobin: 9.4 g/dl, total count: 7290, differential count: N 65%, L 33%, E 2%, platelet count 340 000, erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 13 m/h, BT 1 min 30 s, CT-4 min, Na 136 meq/l, K 4 meq/l, urea 27 mg%, creatine 1 mg%. Total cholesterol 211, low-density lipoprotein 135, high-density lipoprotein 58, TG-90, very low-density lipoprotein 18. HIV, HBV surface antigen, antihepatitis C virus and venereal disease research laboratory were negative

Her S lipoprotein (a) was 28 mg/dl, normal less than 30 mg/dl, her serum homocysteine and her high sensitivity C reactive protein were 0.5 mg/dl (normal l0–0.06 mg/dl)

Differential diagnosis

Systemic hypertension was also considered to be the risk factor for MI.

Treatment

She was taken for primary PCI and the coronary angiography showed a discrete eccentric 99% lesion of proximal RCA with thrombus with TIMI 1 flow distally. Thrombus aspiration was performed with a Thrombuster II device and the lesion was stented with 4×15 Prolink (BMS). TIMI III flow attained (DBT was 45 min) (figures 1–4)

A gynaecology consultation was performed prior to discharge and tranexamic acid and mefenamic acid were stopped. She was put on T. Etamsylate 500 mg three times a day to be taken during menstruation.

Outcome and follow-up

Subsequently she was discharged on fifth postprocedure day. She recently came for follow-up and is doing well.

Discussion

The risk factors for the MI in this 41-year-old premenopausal woman were systemic hypertension, dyslipidaemia (newly detected ) and possibly the intake of the combination of antifibrinolytic agent (tranexamic acid) and NSAIDs.

There are reports of acute MI after the use of tranexamic acid.1

It has recently been reviewed by the British Medical Journal and was believed to be useful in saving lives after heavy bleeding. It was thought to be useful in the Crash 2 trial.2 So the journal was questioning why no one used it. This article specifically describes the risk of MI being between 0.43 and 1.09, the relative risk was 0.68, (p 0.11) that is favourable for the drug. It was believed to reduce the need for blood transfusions. Again they have related the relative risk of deep vein thrombosis as −0.86 (0.53–1.39) (p 0.54), and the relative risk of pulmonary embolism was 0.61 (0.25–1.47 p 0.27). But the relative risk for stroke was high and not beneficial. It was 1.14 (0.65–2 p+0.65). We comment that none of these values show protection from these side effects, hence it is possible that the drug does cause excess thrombosis.2 3

Sirker et al4 described a young woman who developed acute inferior wall MI after tranexamic acid. She also had another bleeding disorder with easy bruising. She had a successful caesarean section on DDavp and tranexamic acid earlier. After a shoulder joint surgery she developed acute MI. The authors commented that in a low-risk situation, which was probably because of tranexamic acid.

This drug is especially harmful in women taking hormonal contraceptives.

Though tranexamic acid causes clotting when bleeding occurs, it does reduce the mortality.5 In a large trial Crash 2, the relative risk of death in heavily bleeding patients was 14% in the tranexamic acid group versus 16% in the placebo group (all cause mortality reduction because of less bleeding) (p 0.0035).

Despite this it is possible that this drug causes coronary thrombosis in susceptible patients. Possibly, along with hypertension this drug might have contributed to acute MI in this patient.

Tranexamic acid is especially to be avoided in obese women and those who smoke as they can develop arterial or venous thrombosis. Our patient was obese. Further it should be avoided in patient using the following: all-trans retinoic acid, Factor IX concentrates and hormonal contraceptives. Occular side-effects and retinal artery occlusion have also been described. Caution should be used when prescribing this drug to renal or hepatic failure patients.

Possible conclusions on tranexamic acid use will come after the results of the ATACAS trial, a randomised trial of aspirin and tranexamic acid in patients with coronary artery bypass grafting. The recruitment of subjects is still going on.6

Learning points.

The present case serves as a warning that, even in patients with an apparently low risk of arterial thrombosis, these drugs may be implicated as a precipitant of myocardial infarction (MI).

Patients taking these drugs and those who prescribe it should therefore be aware of the potential for presentation of such a complication—particularly since this patient group will include many who understandably consider themselves in good general health and are thus liable to disregard important cardiac symptoms.

Prescribers should be aware of this association and seek cardiological consultation promptly for patients who develop chest pain following the administration of tranexamic acid/mefanamic acid.

Furthermore, we recommend that treatment with tranexamic acid and other antifibrinolytic agents/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in patients with risk factors for coronary artery disease, those with recent MI or unstable angina. This also holds true for patients who have had recent percutaneous coronary intervention.

Footnotes

Contributors: .URM drafted the manuscript for the case report. PV, SP and PNG performed the primary angioplasty. PNG reviewed the manuscript and all the authors have actively contributed towards the case report.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mandal AKJ, Missouris CG. Tranexamic acid and acute myocardial infarction. Br J Cardiol 2005;2013:306–7 [Google Scholar]

- 2. The best of pulmonary and critical care medicine, Jan 5 2013, available online. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, et al. The effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ 2012:2013:e3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirker A, Malik N, Bellamy M, et al. Acute myocardial infarction following tranexamic acid use in a low cardiovascular risk setting. Br J Hematol 2008;2013:895–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The CRASH-2 collaborators. The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2011;2013:1096–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myles P, Smith J, Knight J, et al. Aspirin and tranexamic acid for coronary artery surgery(ATACAS)Trial and Design. Am Heart J 2008;2013:224–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]