Abstract

Salivary gland tumours are rare in children and when they do arise, they preferentially affect major salivary glands with sporadic incidence in minor salivary glands. The mucosa of the cheek is an uncommon site of occurrence for intraoral pleomorphic adenoma and most of these cases have been reported in adults. Histologically, it shows a highly variable morphology because of interplay between epithelial and mesenchymal (myxoid, hyaline, chondroid, osseous) elements which arise from same cell clone, which may be a myoepithelial or ductal reserve cell. Here we report a rare case of juvenile pleomorphic adenoma of the cheek in a 12-year-old girl with a predominant epithelial component histologically. Relevant studies are discussed with a focus on its cytology and cytogenetics.

Background

Clinically, pleomorphic adenoma should be in the domain of the dentist while diagnosing well-circumscribed firm swellings of the buccal mucosa.

Histologically, the pathologist should not be deluded by the cellularity in case of pleomorphic adenoma where epithelial component is predominant.

And, its unusual occurrence in a 12-year-old patient, while most of the cases are reported between 30 and 50 years.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old girl reported with slowly growing asymptomatic swelling in the left cheek present since 6 months. On inspection, the left buccal mucosa appeared normal while on palpation a 2×2 cm, firm, well-circumscribed mobile mass was present around 3 cm posterior to the angle of the mouth. There was no history of trauma (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preoperative intraoral photograph of left buccal mucosa.

Investigations

The laboratory tests were non-descript.

Differential diagnosis

It was provisionally diagnosed as fibroma.

Treatment

The mass was dissected and excised with safety margins under local anaesthesia (figures 2 and 3). Grossly, the lesion was round, well-demarcated, encapsulated, greyish white measuring 2×2 cm. On histopathological examination, a well-encapsulated growth arising from the minor salivary gland was perceived. The neoplastic proliferation was composed of sheets of loosely cohesive cells with formation of occasional tubular structures. Round-to-oval cells having eccentric nuclei and scanty pink cytoplasm resembling plasma cells were arranged in small nests admixed with focal aggregates of mucous cells forming mucous pools. Ducts were lined by cuboidal cells with central eosinophilic coagulum. The stroma was predominantly mucoid, with few hyalinised and myxoid areas. Anastomosing bands and fascicles of spindle-shaped cells with foci of squamous metaplasia and focal capsular penetration by tumour cells which were otherwise histologically benign were apparent. Based on these features it was diagnosed as cellular variant of pleomorphic adenoma (figures 4–8).

Figure 2.

Well-circumscribed round mass on left buccal mucosa during surgical excision.

Figure 3.

Excised specimen.

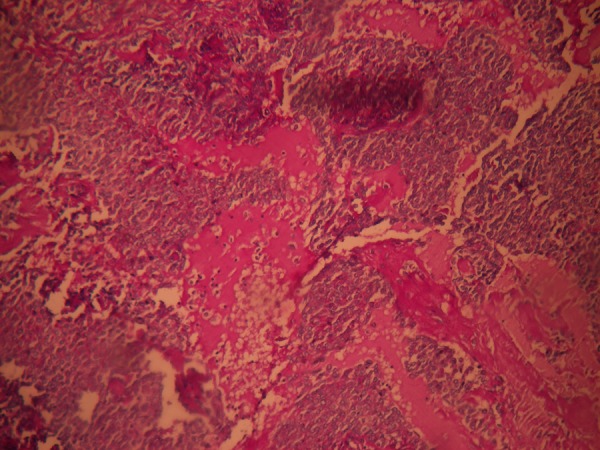

Figure 4.

Periphery of the lesion with capsule surrounding sheets of loosely cohesive cells with foci of mucous goblet cells.

Figure 5.

Periodic acid Schiff staining demonstrating mucous pools.

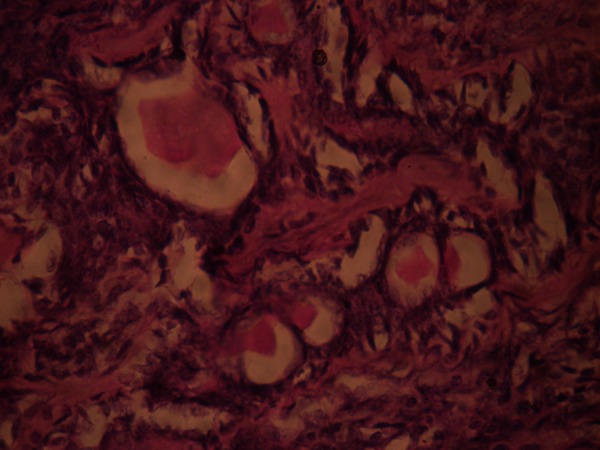

Figure 6.

Ductal structures containing eosinophilic material surrounded by myoepithelial cells.

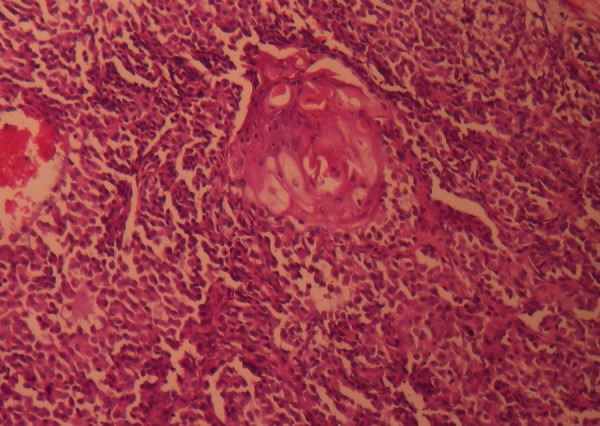

Figure 7.

Plasmacytoid areas (round cells with eccentric nucleus and eosinophilic cytoplasm) with foci of squamous metaplasia.

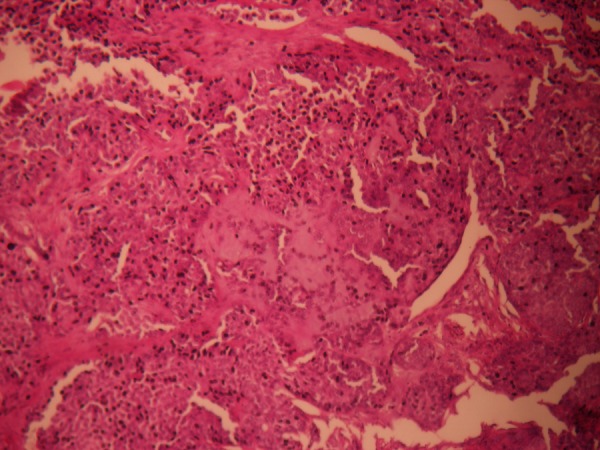

Figure 8.

Eosinophilic hyaline material form bands separating the epithelial cells.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperative period was uneventful. The patient was followed up over a period of 6 months with no recurrence.

Discussion

Intraoral minor salivary gland tumours (IMSGT) comprise an imperative milieu in the field of oral pathology. They are uncommon clinical entities, accounting for 10–25% of all salivary glands tumours. Among the IMSGT, the common type is pleomorphic adenoma (PA). PA occurs at all ages, even occasionally in the newborn with its highest peak in fifth and sixth decades. 1–5 Buchner et al6 determined the relative frequency and distribution of IMSGT. Of the 380 IMSGT studied, 59% were benign and 41% were malignant. Of the benign tumours, PA was the commonest 39.2%, followed by cystadenoma 6.3%, canalicular adenoma 6.1%, ductal papillomas 4.4%, basal cell adenoma 1.6% and myoepithelioma 1.3%. Of the malignant tumours, mucoepidermoid carcinoma was the most common followed by polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified, acinic cell carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma and carcinoma expleomorphic adenoma. PA in juvenile and adolescent patients has its highest incidence in the puberty and the postpuberty age group. Majority of intraoral PA’s involve the palate, followed by the buccal mucosa and then the lips and lastly other rare regions such as floor of mouth, retromolar region and gingiva. Though there is a trivial disparity in site predilection among various reports, consistently all show a female predilection. The most common symptom of intraoral PA is asymptomatic submucosal lump, with a large interval between the first symptoms and diagnosis.7–14

As in this report PA is never the instant primary diagnosis. Although, PA should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis of well-circumscribed swellings of cheek it is barely put in practice. In the circuitous path of eliminating the various possibilities, the buccal space abscess was ruled out in this case owing to the absence of signs of inflammation and an aetiological factor. The lack of ulceration of the buccal mucosa, paresthesia or invasion of the surrounding tissue ruled out the possibility of a malignant lesion. Because of the firm and well-circumscribed nature of the lesion a provisional diagnosis of fibroma was made, however, histologically it turned out to be PA. Customary histological picture of PA integrates immense varieties of cells, architectures and morphological characteristics. Extracellular stroma is one of the defining components of PA, ranging from scanty to abundant. Diagnosis of classical and myxoid type is undemanding; however, cellular type is of much concern. Histological differential diagnosis for cellular PA includes carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, basal cell adenoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma was ruled out as there was no malignant epithelium, mitotic figures, nuclear atypia, infiltration, necrosis and perineurial invasion. Though histologically it resembled solid variant of adenoid cystic carcinoma typical small bland myoepithelial cells with scant cytoplasm and dark compact angular nuclei with pseudoglandular spaces restraining periodic acid Schiff stain positive excess basement membrane material were absent. The basal cell adenoma is composed of basaloid cells sharply delineated from the stroma by basement membrane. The basal cell carcinoma is a low-grade malignancy similar to basal cell adenoma. It is an infiltrative tumour with perineural invasion and vascular invasion; variable cytological atypia and mitotic activity. Apart from absence of all these features, presence of myxoid matrix, squamous differentiation and mucous pools purged the likelihood of the above. The polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma is usually non-encapsulated tumour with diverse growth patterns, infiltrative borders and perineural invasion. Presence of mucous cells and mucoid stroma perplexed with mucoepidermoid carcinoma but the presence of plasmacytoid components established the diagnosis of PA. With less than 30% of mucoid stroma and varied epithelial differentiation this case fits under type 3 in Seifert classification 15–17

Lee et al18 provided the first molecular evidence that the luminal and non-luminal cells in pleomorphic adenomas arise from the same clone in most cases, and the morphologically diverse non-luminal cells are monoclonal using the PCR-based (human androgen receptor gene) assay. Pleiomorphic adenoma gene1 is consistently rearranged in pleomorphic adenoma by translocations t(3;8)(p21;q12) and t(5;8)(p13;q12). It exerts oncogenic effects by inducing growth factor production. The gene product is a nuclear protein that functions as a DNA-binding transcription factor. Detection of such genetic hallmarks using RT-PCR or fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) technique could help diagnose morphologically ambiguous cases.19 20

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of PA is characterised by admixture of cellular and mesenchymal components. The mesenchymal component may be myxoid or chondroid and is usually admixed with spindle-shaped myoepithelial cells. Predominance of myxoid stroma may be mistaken for cystic fluid or mucin associated with mucoepidermoid carcinoma. When the cellular component predominates FNAB may not sample the scant mesenchymal component posing diagnostic difficulties with other salivary gland neoplasms such as basal cell adenoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma. Cellular PA (CPA) has characteristic low-power pattern including the presence of loosely cohesive branching and arborising sheets of intermediate sized cells with indistinct community borders. When myoepithelial cell component is largely spindle shaped, CPA may masquerade as a spindle cell neoplasm where it is difficult to differentiate them based only on cytological criteria. In such cases it is probably best to recommend histological confirmation.21

PAs of minor salivary glands occasionally lack encapsulations and may mix into normal host tissue; hence, a wide excision is necessary with good safety margins. Recurrence tends to develop in young patients where the tumour onset is less than 30 years of age.2 Local recurrence is owing to inadequate resection or rupture of the capsule or tumours spillage as in predominantly mucoid type during excision as these tumours often have microscopic interruptions in the capsule.

Learning points.

Pleomorphic adenoma of the cheek is a rare neoplasm and therefore its diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion that too in a juvenile patient.

The biological behaviour in young patients seems to be similar to that in adults, with a very low recurrence rate after complete surgical resection.

All lesions clinically presenting as fibromas are not fibromas so clinical photographs and other investigative procedure should not be ignored.

Footnotes

Contributors: AA: Preparation of article; SBU: Surgeon.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Atlas of tumor pathology; tumors of the salivary glands. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996; third series. Fascicle 17 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gnepp DR. Salivary gland (major and minor) and lacrimal gland. In: Gnepp DR. Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. 2nd edn Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2009:434–49 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas RB. Pathology of tumors of oral tissues. 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1984:298–9 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krolls SO, Trodahl JN, Boyers RC. Salivary gland lesions in children. A survey of 430 cases. Cancer 1972;2013:459–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byars LT, Ackerman LV, Peacock E. Tumors of salivary gland origin in children: a clinical pathologic appraisal of 24 cases. Ann Surg 1957;2013:40–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of intraoral minor salivary gland tumors: a study of 380 cases from northern California and comparison to reports from other parts of the world. J Oral Pathol Med 2007;2013:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorge J, Pires FR, Alves FA, et al. Juvenile intraoral pleomorphic adenoma: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;2013:273–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellies M, Schaffranietz F, Arglebe C, et al. Tumors of the salivary glands in childhood and adolescence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;2013:1049–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Li Y, He H, et al. Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors in a Chinese population: a retrospective study on 737 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;2013:94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toida M, Shimokawa K, Makita H, et al. Intraoral minor salivary gland tumors: a clinicopathological study of 82 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;2013:528–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldron CA, Gnepp DR. Tumors of the intraoral minor salivary glands: a demographic and histologic study of 426 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1988;2013:323–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frable WJ, Elzay RP. Tumors of minor salivary glands. A report of 73 cases. Cancer 1970;2013:932–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kara MI, Goze F, Ezirganli Ş, et al. Neoplasms of the salivary glands in a Turkish adult population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2010;2013:e880–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito FA, Ito K, Vargas PA, et al. Salivary gland tumors in a Brazilian population: a retrospective study of 496 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;2013:533–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seifert G, Langrock I, Donath K. A pathological classification of pleomorphic adenoma of the salivary glands (author's transl). HNO 1976;2013:415–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito FA, Jorge J, Vargas PA, et al. Histopathological findings of pleomorphic adenomas of the salivary glands. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009;2013:E57–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mărgăritescu C, Raica M, Simionescu C, et al. Tumoral stroma of salivary pleomorphic adenoma—histopathological, histochemical and immunohistochemical study. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2005;2013:211–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee PS, Sabbath-Solitare M, Redondo TC, et al. Molecular evidence that the stromal and epithelial cells in pleomorphic adenomas of salivary gland arise from the same origin: clonal analysis using Human Androgen Receptor Gene (HUMARA) Assay. Hum Pathol 2000;2013:498–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuyama A, Hisaoka M, Nagao Y, et al. Aberrant PLAG1 expression in pleomorphic adenomas of the salivary gland: a molecular genetic and immunohistochemical study. Virchows Arch 2011;2013:583–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandasamy J, Smith A, Diaz S, et al. Heterogeneity of PLAG1 gene rearrangements in pleomorphic adenoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2007;2013:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsheikh TM, Bernacki EG. Fine needle aspiration cytology of cellular pleomorphic adenoma. Acta Cytol 1996;2013:1165–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]