Abstract

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been recently introduced for treatment of different malignancies. Various cardiovascular toxicities have been reported with TKIs with hypertension being the most common adverse cardiovascular event. We report a case of a 60-year-old woman who developed left renal artery stenosis associated with renal atrophy in the context of metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Renal atrophy was noticed during serial imaging studies to monitor cancer therapy. Clinically, she was asymptomatic without significant change in blood pressure. The glomerular filtration rate dropped from 88 ml/min/1.73 m2 at baseline to 56 ml/min/1.73 ml/min and partially recovered to 71 ml/min/1.73 m2 after renal artery stenting. To our knowledge, this will be the first known case of renal artery stenosis associated with TKI use. Physicians may need to investigate the possibility of developing renal artery stenosis in patients with unexplained worsening in kidney functions while on TKIs.

Background

Sorafenib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with activity against transmembrane KIT, Flt-3, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2 (VEGFR-2), VEGFR-3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-B and intracellular c-Raf and BRAF. Sorafenib has been approved for advanced renal cell carcinoma and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and has been studied in patients with progressive metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma.1 2

Hypertension is the most common cardiovascular event associated with TKI use, including sorafenib. Other clinical events related to cardiovascular toxicities include left ventricular dysfunction and arterial thromboembolic events (ATE).3–8

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is the most common potentially correctable cause of secondary hypertension that is often associated with atherosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia. RAS has not been reported before in association with any TKI, including sorafenib.

Here, we report the first known case of RAS associated with TKI use. In our case, RAS was associated with renal atrophy and occurred in the context of metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma treated with sorafenib.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old African American woman was referred to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eight years before the presentation, she was diagnosed with a follicular variant of papillary carcinoma, for which she underwent total thyroidectomy. The tumour was 1.4 cm in size and had no extrathyroidal or lymphovascular invasion (stage 1 (T1 N0 M0)). The patient received three doses of radioactive iodine, one immediately after the initial tumour resection and then two more treatments a few years later for slowly growing subcentimeter lung nodules that eventually proved to be non-iodine-avid metastases. Her medical history was only significant for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and well-controlled hypertension. There was no history of stroke, coronary artery disease or peripheral vascular disease. Her medication list included esomeprazole, felodipine, furosemide, lisinopril, aspirin and levothyroxine. The patient denied any history of smoking or heavy alcohol use. Her family history was remarkable for hypertension with no premature cardiovascular events or thyroid cancer. On presentation to MDACC, her blood pressure was 136/77 mm Hg and heart rate 80 pulse/min. The physical examination was unremarkable except for an evidence of the prior total thyroidectomy. Fasting blood glucose was in the 80–90 mg/dl (4.44–4.99 mmol/l) range. The patient's baseline fasting lipid profile was as follows: 169 mg/dl (4.37 mmol/l) total cholesterol, 108 mg/dl (2.79 mmol/l) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, 48 mg/dl (1.24 mmol/l) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and 63 mg/dl (0.71 mmol/l) triglycerides. Owing to the small size of the lung metastases and the absence of symptoms, she was carefully monitored with serial CT scans. Subsequently, she was started on 200 mg sorafenib twice daily, which was incrementally increased to 400 mg twice daily, due to progressive disease in the lungs and mediastinum. She tolerated this treatment well, experiencing only mild diarrhoea, alopecia and weight loss. During sorafenib treatment, her disease initially stabilised for about 24 months then progressed with the development of new bone metastases.

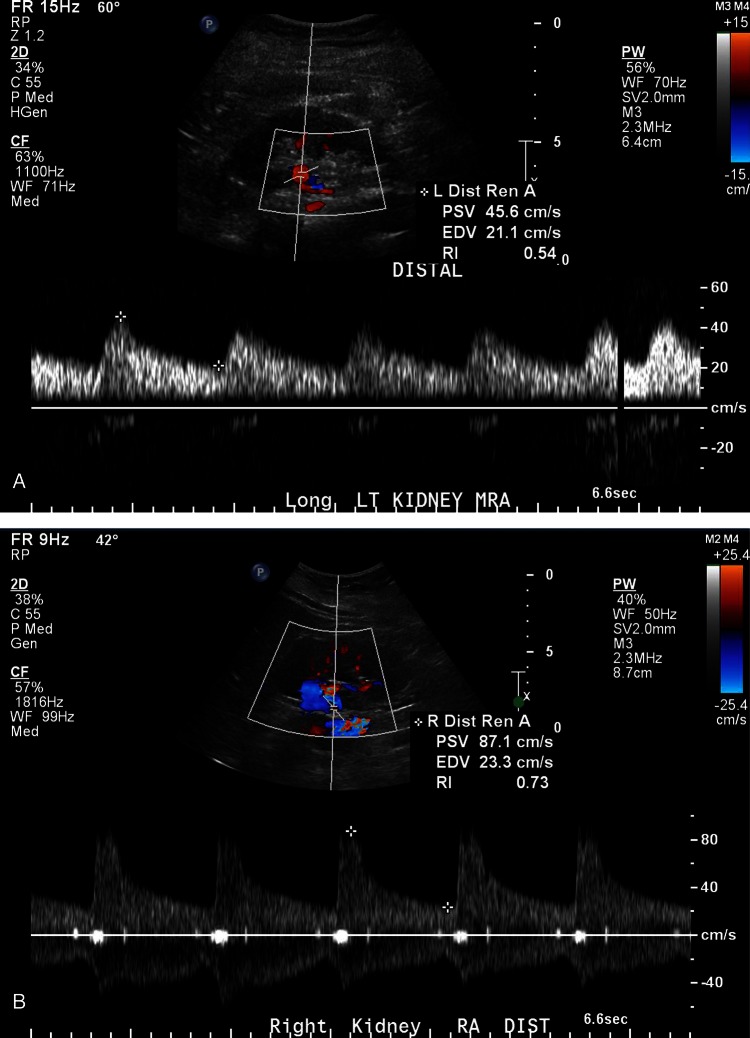

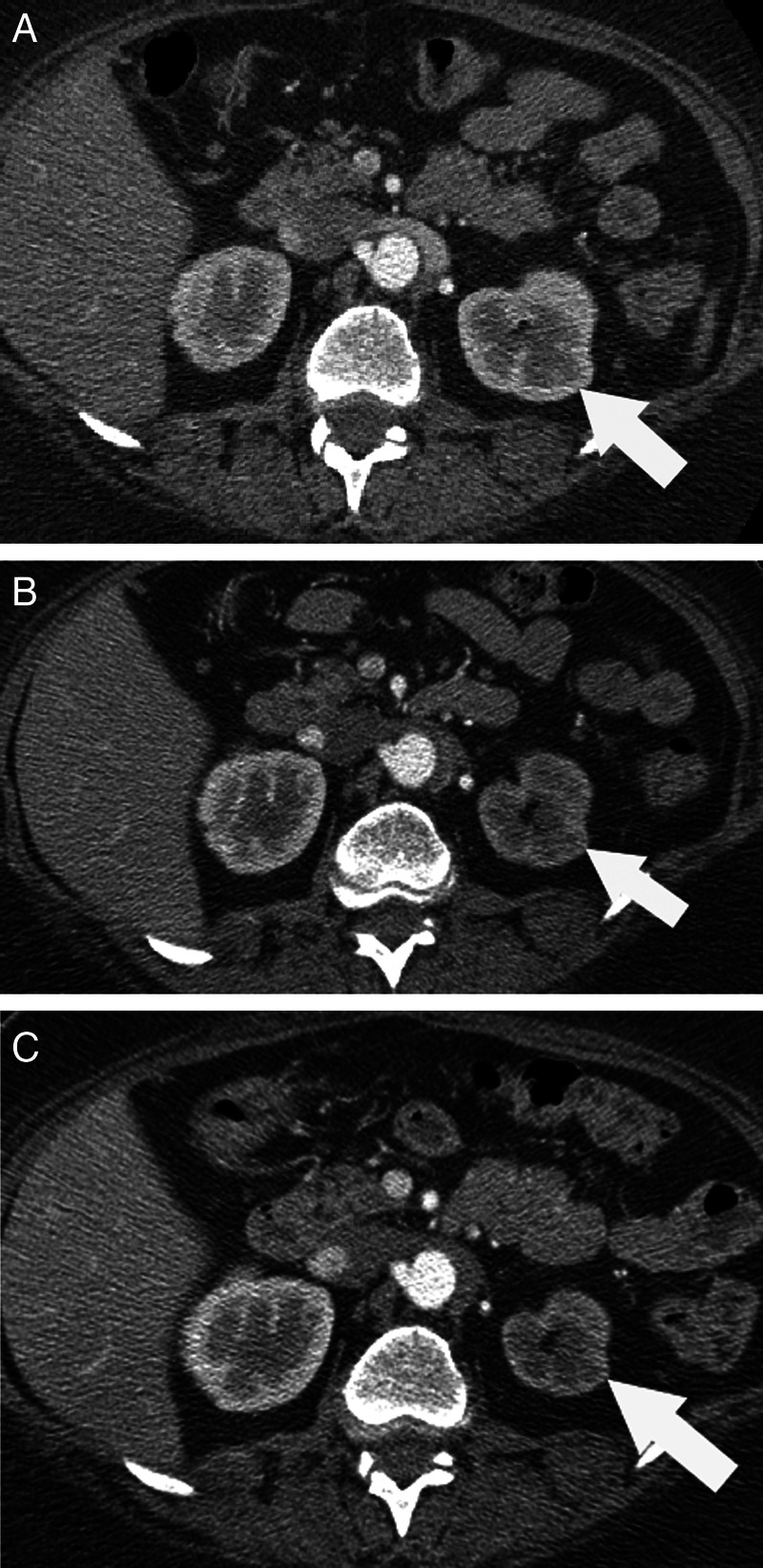

During her treatment course, the patient was noted to have a progressive decrease in the size of the left kidney with cortical atrophy, which was suspicious for RAS (figure 1). RAS was further supported by ultrasonography of the kidneys with Doppler analysis (figure 2). Meanwhile, the patient's blood pressure remained fairly well controlled without any change in her medications; her creatine level rose slightly, from an average of 0.8 mg/dl (70.7 µmol/l; corresponding to a calculated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 88 ml/min/1.73 m2 (1.47 ml/s/1.73 m2)) at baseline to 1.19 mg/dl (105.2 µmol/l; corresponding to a calculated GFR of 56 ml/min/1.73 ml/min (0.93 ml/s/1.73 m2)); and her potassium and bicarbonate levels stayed within the normal ranges. Sorafenib treatment was stopped after displaying disease progression and RAS was confirmed via angiography.

Figure 1.

(A) Axial abdominal CT images; prior to sorafenib treatment (A) the right and left kidneys showed similar size and enhancing characteristics on this corticomedullary phase abdominal CT (white arrow referring to left kidney). Twenty months on therapy (B), the left kidney (white arrow) showed delayed enhancement compared with the right, and there was selective loss cortical thickness. Twenty-four months on therapy (C), there was further left renal volume loss (white arrow) and grossly delayed and impaired contrast enhancement.

Figure 2.

(A) Doppler examinations of the distal main renal arteries revealed a markedly slowed upstroke on the left (A) with a very slow fall in flow after peak velocity (pulsus tardus et parvus) with a peak systolic flow of about 46 cm/s, end diastolic flow of 21 cm/s and a resistive index of 0.54. The left renal arterial Doppler study also showed a very turbulent flow pattern in the vessel, all consistent with proximal vascular stenosis. The right renal flow pattern in (B) showed a normal sharp upstroke, and rapid decay pattern, with a peak systolic flow of 87 cm/s, end diastolic flow of 23 cm/s and a resistive index of 0.73).

Treatment

She underwent renal artery angioplasty with stenting, and her renal functions improved slightly 3 months later (her creatine level dropped to 0.96 mg/dl (84.9 µmol/l corresponding to a calculated GFR of 71 ml/min/1.73 m2 (1.18 ml/s/1.73 m2)).

Discussion

TKIs have been used for treatment of different malignancies. Common toxicities associated with TKIs include reversible skin rashes, hand and foot skin reaction, hypertension, haemorrhage, diarrhoea, hypophosphataemia, leucopaenia, elevated pancreatic enzymes levels and proteinuria.3 4 Other toxicities include left ventricular ejection fraction dysfunction, ATE and coronary artery disease due to arterial vasospasm.3–11

RAS is the most common potentially correctable cause of secondary hypertension. Recent imaging studies indicate that ‘incidental’ vascular lesions can be identified in 3–5% of normotensive subjects.12 The incidence varies with the clinical setting. However, RAS has never been reported in association with TKIs. By far, the most common renovascular lesion is atherosclerotic RAS. Fibromuscular dysplasia is the second-most-common reason for RAS and is detected most often in young women.

In situ thrombosis of a renal artery is a rare cause of RAS. It is typically superimposed upon pre-existing atherosclerotic renovascular disease or occurs after a traumatic intimal tear. In situ cardiovascular thrombosis has been reported with bevacizumab.13–15 To our knowledge, in situ thrombosis of a renal artery has never been described with the use of any TKI. The molecular mechanism of arterial thromboembolism has not been well investigated, but it seems to be multifactorial. VEGF stimulates endothelial cell proliferation to maintain vascular structure. The inhibition of VEGF signalling pathway decreases the endothelial cells regeneration which leads to vascular wall defects and exposes subendothelial procoagulant phospholipids. VEGF inhibitors may also increase blood viscosity by stimulating erythropoietin production.3 16

The lack of strong background risk for atherosclerotic RAS in our patient and the rapid progression of renal atrophy increase the suspicion for the association between RAS and sorafenib treatment via in situ thrombotic mechanism as discussed above, although the possibility of an atherosclerotic process accelerated by sorafenib use could be an alternative explanation. It is likely that the RAS process began since sorafenib was started and the stenosis became critical during therapy.

Learning points.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are associated with different cardiovascular toxicities.

Physicians may need to investigate the possibility of developing renal artery stenosis (RAS) in patients with unexplained worsening in kidney functions while on TKIs.

Unilateral RAS may not necessarily result in worsening in hypertension control.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed to the following: conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data;drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, andfinal approval of the version published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kloos RT, Ringel MD, Knopp MV, et al. Phase II trial of sorafenib in metastatic thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;2013:1675–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta-Abramson V, Troxel AB, Nellore A, et al. Phase II trial of sorafenib in advanced thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;2013:4714–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudes GR, Carducci MA, Choueiri TK, et al. NCCN Task Force report: optimizing treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma with molecular targeted therapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011;2013:S1–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stadler WM, Figlin RA, McDermott DF, et al. Safety and efficacy results of the advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program in North America. Cancer 2010;2013:1272–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;2013:125–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranpura V, Hapani S, Chuang J, et al. Risk of cardiac ischemia and arterial thromboembolic events with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Oncol 2010;2013:287–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards CJ, Je Y, Schutz FA, et al. Incidence and risk of congestive heart failure in patients with renal and nonrenal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Clin Oncol 2011;2013:3450–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choueiri TK, Schutz FA, Je Y, et al. Risk of arterial thromboembolic events with sunitinib and sorafenib: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2010;2013:2280–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naib T, Steingart RM, Chen CL. Sorafenib-associated multivessel coronary artery vasospasm. Herz 2011;2013:348–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arima Y, Oshima S, Noda K, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery spasm. J Cardiol 2009;2013:512–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porto I, Leo A, Miele L, et al. A case of variant angina in a patient under chronic treatment with sorafenib. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010;2013:476–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz EC, Vrtiska TJ, Lieske JC, et al. Prevalence of renal artery and kidney abnormalities by computed tomography among healthy adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;2013:431–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roncalli J, Delord JP, Galinier M, et al. Bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: a left intracardiac thrombotic event. Ann Oncol 2006;2013:1177–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon S, Schmassmann-Suhijar D, Zuber M, et al. Chemotherapy with bevacizumab, irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (IFL) associated with a large, embolizing thrombus in the thoracic aorta. Ann Oncol 2006;2013:1851–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah MA, Ilson D, Kelsen DP. Thromboembolic events in gastric cancer: high incidence in patients receiving irinotecan- and bevacizumab-based therapy. J Clin Oncol 2005;2013:2574–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer 2007;2013:1788–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]