Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease is increased among HIV-infected patients, but little is known regarding ischemic stroke rates. We sought to compare stroke rates and determine stroke risk factors in HIV versus non-HIV patients.

Methods

An HIV cohort and matched non-HIV comparator cohort seen between 1996 and 2009 were identified from a Boston health care system. The primary endpoint was ischemic stroke, defined using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. Unadjusted stroke incidence rates were calculated. Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to determine adjusted hazard ratios (HR).

Results

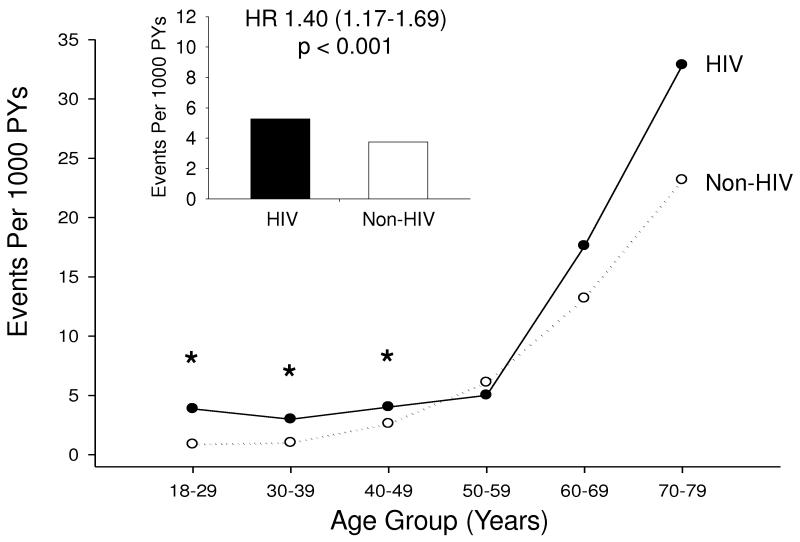

The incidence rate of ischemic stroke was 5.27 per 1000 person years (PY) in HIV compared with 3.75 in non-HIV patients, with an unadjusted HR of 1.40 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.17-1.69, P<0.001). HIV remained an independent predictor of stroke after controlling for demographics and stroke risk factors (1.21, 1.01-1.46, P=0.043). The relative increase in stroke rates (HIV vs. non-HIV) was significantly higher in younger HIV patients (incidence rate ratio 4.42, 95% CI 1.56-11.09 age 18-29; 2.96, 1.69-4.96 age 30-39; 1.53, 1.06-2.17 age 40-49), and in women (HR 2.16 [1.53-3.04] for women vs. 1.18 [0.95-1.47] for men). Among HIV patients, increased HIV RNA (HR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04-1.17, P=0.001) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.

Conclusions

Stroke rates were increased among HIV-infected patients, independent of common stroke risk factors, particularly among young patients and women.

Keywords: HIV, stroke, cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, vascular risk factors

Introduction

Despite data supporting an association between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cardiovascular disease (CVD),[1-4] the effect of HIV on the risk of stroke remains unclear. Most early studies evaluating the incidence of stroke in individuals with HIV were confounded by advanced HIV infection and associated opportunistic infections or malignancy.[5-7] Although a growing body of literature exists describing cardiovascular risk in patients with HIV in the modern era of antiretroviral therapy (ART), little is known about the incidence of and risk factors for ischemic stroke in these patients, the majority of whom demonstrate well-controlled HIV infection.

The proportion of ischemic strokes attributed to HIV-infected persons was found to increase in the United States from 1997 to 2006, but stroke incidence rates comparing HIV to non-HIV patients were not calculated.[8] A recent study demonstrated increased rates of cerebrovascular events in Danish HIV patients compared to a population-based control group but was not able to account for multiple potentially confounding variables including smoking and non-ART medication use.[9] Previous retrospective case-control studies have identified potential predictors of stroke in HIV-infected individuals with stroke compared to those without a history of stroke.[10, 11] This study significantly expands on existing knowledge by comparing the incidence of stroke as a specific primary endpoint in individuals with HIV to a control population of non HIV-infected patients accounting for multiple vascular risk factors.

In the present study, we determined the incidence of ischemic stroke in HIV-infected patients seen at two hospitals and their affiliated outpatient clinics comprising a large U.S. health care system, compared to a matched HIV-negative control group. We investigated whether HIV is independently associated with stroke, the relationship of HIV infection to traditional vascular risk factors, and potential stroke risk factors unique to HIV-infected individuals.

Methods

Study design and patient population

We analyzed a cohort of 4,308 HIV-infected individuals from the Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR), a clinical care database of all inpatient and outpatient encounters from Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the two primary facilities of Partners HealthCare System. All HIV-infected individuals with at least one clinical encounter between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2007 were included in the cohort. HIV infection was determined by International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 042 or V08, previously ascertained by a trained clinical nurse to be 99% sensitive and 89% specific for clinical HIV infection. A control group was generated by matching non-HIV patients from the RPDR to patients in the HIV cohort in a 10:1 ratio on the basis of age, gender, and race. Within the HIV and control cohorts, patients who were 18 years of age or older at the start of the observation period and had at least one inpatient or two outpatient encounters were eligible for the study. Patients were excluded if any stroke diagnosis preceded HIV diagnosis or if stroke occurred prior to 1996. The Partners Human Research Committee approved the study.

The start of the observation period was defined as the latest of the three possible entry triggers: January 1, 1996, first ICD-9-CM code for HIV, or first encounter for controls. The end of the observation period was defined as the earliest of three possible termination points: stroke event, last encounter if no stroke occurred, or December 31, 2009. Patients with multiple ICD-9-CM codes for stroke were counted only once and were censored after the initial stroke event, considered to occur on the date of the first qualifying code.

Outcome

The primary endpoint was ischemic stroke, defined as at least one inpatient or two outpatient encounters documented with an ICD-9-CM code selected from the category of ischemic cerebrovascular disease (433, 433.01, 433.1, 433.11, 433.2, 433.21, 433.3, 433.31, 433.8, 433.81, 433.9, 433.91, 434, 434.0, 434.00, 434.01, 434.1, 434.11, 434.9, 434.91, 437, 437.4, 437.5, 443.21, and 443.24). Intracranial hemorrhage was not included as an endpoint due to a discrete risk factor profile and transient ischemic attack was not included due to potential lack of specificity of ICD-based diagnosis.

Validation of the ICD-9-CM codes used for the primary endpoint was performed by a neurologist using the following criteria adapted from the World Health Organization MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) project: 1. Rapidly developing clinical signs of a new focal disturbance of cerebral function lasting more than 24 hours with no apparent alternative cause; 2. No history, physical findings, or diagnostic evaluation consistent with another cause, including trauma, seizure, migraine or space-occupying lesion; 3. Brain imaging, if available, consistent with acute infarct.[12] Use of a single inpatient ICD code or two of the selected outpatient codes for ischemic stroke maximized the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65-0.85).

Covariates

Traditional stroke risk factors were defined by the specified ICD-9-CM codes and their subcategories applied during the observation period and prior to stroke diagnosis or by corresponding codes used within the Partners HealthCare System electronic health records (Table 1). Smoking status was ascertained by use of a natural language processing tool, as described previously.[13] Documentation permitting the determination of smoking status was available in the large majority of patients, including 84% of HIV and 77% of non-HIV patients. Patients without smoking-related documentation in the chart were considered non-smokers. Medication information was extracted for inpatients and outpatients. Antiretroviral medications were classified according to the three major classes during the observation period (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NRTI], non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTI] and protease inhibitors [PI]) and were represented in the primary model as ever versus never use. Data on hormonal contraception medication use was not available. CD4 cell count and HIV RNA laboratory data were collected.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Cohorts*

| HIV (N=4,308) | Control (N=32,423) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD)† | 41.6 (11.4) | 40.8 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Women, No. (%) | 1350 (31) | 11204 (35) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.001 | ||

| White, No. (%) | 2267 (53) | 16919 (52) | |

| Black, No. (%) | 899 (21) | 7288 (22) | |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 724 (17) | 5604 (17) | |

| Other, No. (%) | 133 (3) | 862 (3) | |

| Unknown, No. (%) | 285 (7) | 1750 (5) | |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 1600 (37) | 10149 (31) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 956 (22) | 4830 (15) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, No. (%) | 1734 (40) | 9633 (30) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, No. (%) | 2070 (48) | 9699 (30) | <0.001 |

| Structural heart disease‡, No. (%) | 675 (16) | 3105 (10) | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy, No. (%) | 201 (5) | 1024 (3) | <0.001 |

| Valvular heart disease, No. (%) | 426 (10) | 2007 (6) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure, No. (%) | 341 (8) | 1426 (4) | <0.001 |

| Endocarditis, No. (%) | 153 (4) | 244 (1) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, No. (%) | 137 (3) | 1092 (3) | 0.519 |

| Acute myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 334 (8) | 1602 (5) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease, No. (%) | 772 (18) | 4572 (14) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin use, No. (%) | 850 (20) | 6026 (19) | 0.07 |

| Warfarin use, No. (%) | 241 (6) | 1494 (5) | 0.004 |

| Statin use, No. (%) | 695 (16) | 5738 (18) | 0.01 |

| NRTI use, No. (%)§ | 2001 (95) | N/A | |

| NNRTI use, No. (%)§ | 1178 (56) | N/A | |

| PI use, No. (%)§ | 1406 (67) | N/A | |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean (SD)∥ | 473 (317) | N/A | |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean (SD)¶ | 271 (252) | N/A | |

| HIV RNA (log, copies/mL), median (IQR)∥ | 0 (0, 868) | N/A | |

| HIV RNA≤400 copies/ml, No. (%)∥ | 1716 (73) | N/A | |

| CNS infection/malignancy, No. (%) | 153 (4) | 39 (<1) | <0.001 |

| Duration follow-up in years, mean (SD) | 5.9 (4.1) | 6.4 (4.7) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; ART = antiretroviral therapy; NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI = protease inhibitor; CNS = central nervous system.

ICD-9-CM codes used to identify diagnoses: hypertension, 401; diabetes mellitus, 250; dyslipidemia, 272 (excluding 272.3 and 272.6), cardiomyopathy, 425; valvular heart disease, 394-396,398.91,424.0, 424.1; heart failure, 428.0, 428.1, 428.2, 428.4. 428.9; endocarditis, 421, 424.9; atrial fibrillation/flutter, 427.3; acute myocardial infarction, 410; coronary heart disease, 410-414 (excluding 413.1); CNS infection/malignancy, 013 (tuberculosis), 321.0 (cryptococcus), 112.83 (candida), 054.3, 054.72 (herpes simplex virus), 130.0 (toxoplasma), 053.0, 053.10 (herpes zoster virus), 046.3 (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy) , 200.5 (CNS lymphoma), 094.81, 094.9, 094.2, 091.81 (syphilis). All subtypes included unless otherwise indicated.

At beginning of observation period.

Any ICD-9-CM code from cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease or heart failure.

Percentages are from patients with ART data available (N=2105).

Most recent value prior to end of observation.

Lowest at any point during observation period.

Statistical analysis

The rates of stroke risk factors, HIV parameters including ART use, infections and malignancy affecting the central nervous system (CNS), and measures of health care use were calculated for the HIV cohort and control group when applicable. χ2 tests were used to compare categorical baseline characteristics between the HIV and non-HIV cohorts. Unadjusted incidence rates of ischemic stroke per 1000 person-years (PY) of observation time were determined for the two cohorts and after stratification by gender and decade of age. We calculated unadjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for stroke by HIV status, stratified by age and gender. To determine whether HIV infection is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke, we tested a series of Cox proportional hazards models. The first model predicted risk of stroke associated with HIV status controlling for age, gender, and race (white vs. nonwhite). The second model added established risk factors for ischemic stroke (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, structural heart disease defined as at least one diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, left-sided valvular heart disease or heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and potential protective factors including aspirin use and warfarin use). To assess whether an association between HIV and stroke might be mediated by HIV-related variables and measures of disease progression independent of demographic characteristics and stroke risk factors, we constructed exploratory HIV-stratified models given the more limited number of events with the HIV-only model. Covariates in the HIV-only model included ART use, CD4 cell count nadir during the observation period in increments of 50 units, recent viral load (log-transformed), endocarditis, and a history of CNS infection or malignancy. Analyses were conducted using Stata (StataCorp, 2008. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation). All tests were two-sided with P values < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 1 outlines the demographic and clinical characteristics in the HIV and non-HIV cohorts. The HIV cohort consisted of 4,308 patients and the control cohort of 32,423 patients. The groups were closely matched on age, gender, and race as expected; however, the small observed differences were statistically significant. The mean duration of observation was 5.9 years for the HIV cohort and 6.4 years for the non-HIV cohort (P < 0.001).

The proportion of HIV-infected patients with traditional stroke risk factors including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, cardiomyopathy, left-sided valvular heart disease, and heart failure was significantly higher than in the non-HIV cohort (P<0.001 for all comparisons). Only the proportion with atrial fibrillation/flutter was similar between the two groups (3%, P=0.519). Rates of acute myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease were significantly elevated among HIV-infected patients. With regard to medication utilization, the rate of warfarin use was significantly higher in the HIV cohort than in the non-HIV group (6 vs. 5%, P=0.004), while there was a trend for increased use of aspirin in the HIV group (20 vs.19%, P=0.07).

Rates of ischemic stroke

Stroke incidence rates are presented in Table 2. In total, 36,731 patients (4,308 HIV and 32,423 non-HIV) contributed 233,700 PY (25,100 from the HIV and 208,600 from the non-HIV cohort) during the observation period. Ischemic stroke was identified in 914 patients, 132 in the HIV cohort and 782 in the non-HIV cohort. The incidence rate of ischemic stroke was 5.27 per 1000 PY in HIV patients compared with 3.75 per 1000 PY in non-HIV patients, resulting in an unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.40 (95% CI 1.17-1.69, P<0.001) (Figure). Unadjusted age-stratified incidence rates and IRR demonstrate that HIV infection was associated with higher rates of stroke among those under 50, but not among older patients (Figure). This effect was more pronounced in women, where it was seen for each age stratum under 50, than in men where only those HIV patients age 30-39 years had elevated stroke rates.

Table 2.

Incidence Rates and Hazard Ratios for Ischemic Stroke*

| All | Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | Control | IRR (95% CI) |

P value |

HIV | Control | IRR (95% CI) |

P value |

HIV | Control | IRR (95% CI) |

P value |

||

| Events | 132 | 782 | 40 | 177 | 92 | 605 | |||||||

| Age Group | |||||||||||||

| 18-29 | 25 | 3.87 | 0.88 | 4.42 (1.56- 11.09) |

0.004 | 5.83 | 0.79 | 7.34 (1.93- 24.39) |

0.002 | 2.11 | 0.98 | 2.15 (0.23- 10.40) |

0.351 |

| 30-39 | 82 | 3.00 | 1.02 | 2.96 (1.69-4.96) | <0.001 | 3.29 | 0.62 | 5.31 (1.95- 13.34) |

<0.001 | 2.84 | 1.28 | 2.23 (1.07-4.26) | 0.022 |

| 40-49 | 229 | 4.02 | 2.62 | 1.53 (1.06-2.17) | 0.02 | 3.90 | 1.67 | 2.34 (1.08-4.65) | 0.021 | 4.06 | 3.09 | 1.31 (0.84-1.97) | 0.194 |

| 50-59 | 256 | 5.01 | 6.09 | 0.82 (0.52-1.24) | 0.355 | 3.76 | 3.81 | 0.99 (0.31-2.49) | 0.999 | 5.46 | 7.06 | 0.77 (0.46-1.23) | 0.272 |

| 60-69 | 174 | 17.60 | 13.19 | 1.33 (0.83-2.06) | 0.198 | 18.47 | 7.34 | 2.52 (0.85-6.25) | 0.063 | 17.33 | 15.84 | 1.09 (0.63-1.80) | 0.702 |

| 70-79 | 101 | 32.86 | 23.17 | 1.42 (0.71-2.60) | 0.264 | 17.17 | 17.45 | 0.98 (0.11-3.92) | 0.999 | 40.20 | 27.03 | 1.49 (0.68-2.92) | 0.254 |

| >=80 | 47 | 30.47 | 29.40 | 1.04 (0.32-2.62) | 0.895 | 34.19 | 22.26 | 1.54 (0.29-5.31) | 0.485 | 26.19 | 37.60 | 0.70 (0.08-2.79) | 0.681 |

| Models | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 5.27 | 3.75 | 1.40 (1.17-1.69) | <0.001 | 5.02 | 2.31 | 2.16 (1.53-3.04) | <0.001 | 5.38 | 4.59 | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | 0.14 | |

| Model 1† | 1.34 (1.11-1.61) | 0.002 | 2.02 (1.43-2.86) | <0.001 | 1.17 (0.94-1.46) | 0.165 | |||||||

| Model 2‡ | 1.21 (1.01-1.46) | 0.043 | 1.76 (1.24-2.52) | 0.002 | 1.05 (0.84-1.32) | 0.639 | |||||||

Abbreviations: IRR = incidence rate ratio; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Rates are per 1000 person years.

Adjusted for age, gender, and race (white vs. other race).

Adjusted for variables in model 1 and hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking (ever vs. never), structural heart disease (at least one diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, left-sided valvular heart disease, or heart failure), atrial fibrillation/flutter, aspirin use, warfarin use.

Figure 1.

Stroke Rates in HIV-Infected versus Non HIV-Infected Patients

Ischemic stroke incidence rates per 1000 PY are shown. The bars indicate incidence rates in the overall HIV (black) and non-HIV (white) cohorts. The lines indicate incidence rates by age group, comparing the HIV (black, solid line) and non-HIV (white, dotted line) cohorts. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences. The hazard ratio for stroke given HIV infection was 1.40 (95% CI 1.17-1.69, P < 0.001).

The association between HIV and stroke remained significant and was only minimally attenuated after adjustment for age, gender, and race in a multivariable model (Model 1). After controlling for traditional stroke risk factors, HIV remained an independent predictor of stroke (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.01-1.46, P=0.043) (Model 2, Table 2).

In gender-specific Cox proportional hazard models, the hazard ratio for HIV-infection was statistically significant for women (HR 2.16; 95% CI 1.53-3.04, P<0.001) but not men (HR 1.18; 95% CI 0.95-1.47, P=0.14). The association between ischemic stroke and HIV infection remained statistically significant in women after adjusting for demographics alone or demographics and established stroke risk factors (Table 2).

Predictors of stroke

In addition to HIV status, other significant predictors of ischemic stroke in the overall group included age, hypertension, smoking, structural heart disease, and atrial fibrillation (Table 3). Dyslipidemia was associated with a decreased risk of stroke. The fully adjusted overall model showed female gender to be associated with a decreased risk of stroke, despite the higher relative contribution of HIV to stroke risk among women in gender-stratified models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Ischemic Stroke in Gender-Stratified Models

| Total | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| HIV infection | 1.21 (1.01-1.46) | 0.043 | 1.76 (1.24-2.52) | 0.002 | 1.05 (0.84-1.32) | 0.639 |

| Female gender | 0.59 (0.51-0.69) | <0.001 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Age | 1.07 (1.06-1.08) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.05-1.07) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.07-1.08) | <0.001 |

| White race (vs. all others) | 0.98 (0.85-1.13) | 0.780 | 0.92 (0.69-1.24) | 0.597 | 1.01 (0.86-1.19) | 0.869 |

| Hypertension | 1.22 (1.04-1.44) | 0.013 | 1.41 (1.01-1.99) | 0.046 | 1.19 (0.99-1.43) | 0.061 |

| Diabetes | 1.10 (0.93-1.29) | 0.259 | 1.03 (0.74-1.44) | 0.854 | 1.11 (0.92-1.34) | 0.271 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.71 (0.61-0.83) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.53-0.99) | 0.044 | 0.71 (0.60-0.84) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (ever vs. never) | 1.28 (1.12-1.47) | <0.001 | 1.20 (0.90-1.60) | 0.210 | 1.30 (1.12-1.52) | 0.001 |

| Structural heart disease | 2.25 (1.91-2.65) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.53-2.97) | <0.001 | 2.28 (1.89-2.75) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1.34 (1.06-1.70) | 0.014 | 1.60 (0.96-2.66) | 0.072 | 1.28 (0.98-1.67) | 0.068 |

| Aspirin use | 0.77 (0.66-0.91) | 0.002 | 1.00 (0.71-1.40) | 0.996 | 0.71 (0.59-0.86) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin use | 0.68 (0.53-0.88) | 0.003 | 0.70 (0.41-1.20) | 0.196 | 0.67 (0.51-0.89) | 0.005 |

Abbreviations: HR = hazard ratio.

Within the HIV cohort, atrial fibrillation (HR 3.15, 95% CI 1.26-7.87, P=0.014), age (HR 1.06 per year, 95% CI 1.03-1.09, P<0.001), a higher log-transformed viral load (HR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04-1.17, P=0.001), and a history of CNS infections or malignancy (HR 2.75, 95% CI 1.26-6.03, P=0.011) were associated with an increased risk of stroke. NNRTI use (vs. no NNRTI use) was associated with a decreased risk of stroke when represented as ever use (HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.19-0.76, P=0.006) but not when represented as duration of use (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.73-1.10, P=0.30). Longer duration of any ART use, however, was associated with a significantly decreased risk of stroke (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.73-0.88, P=<0.001). When evaluated as a dichotomous variable, an undetectable viral load defined as HIV RNA ≤ 400 copies/ml was associated with a decreased risk of stroke (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25-0.81, P=0.008). CD4 cell count was not significantly associated with stroke when included as either the nadir value (Table 4) or the most recent value (HR 0.98 per 50 unit increment, 95% CI 0.93-1.03, P=0.46). Significant risk factors for stroke among the non-HIV cohort are also shown in Table 4, and are generally similar to those reported previously.[14]

Table 4.

Hazard Ratios for Stroke in HIV-Stratified Models

| HIV (N= 2255) | Control (N=32423) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Female gender | 0.97 (0.50-1.89) | 0.921 | 0.54 (0.46-0.65) | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.06 (1.03-1.09) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.07-1.08) | <0.001 |

| White race (vs. all others) | 1.40 (0.80-2.46) | 0.235 | 0.99 (0.85-1.15) | 0.846 |

| Hypertension | 0.79 (0.44-1.45) | 0.451 | 1.30 (1.09-1.55) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 0.59 (0.28-1.23) | 0.159 | 1.17 (0.98-1.39) | 0.077 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.99 (0.55-1.80) | 0.987 | 0.75 (0.63-0.88) | 0.001 |

| Smoking (ever vs. never) | 0.83 (0.49-1.40) | 0.483 | 1.29 (1.11-1.49) | 0.001 |

| Structural heart disease | 1.24 (0.62-2.44) | 0.544 | 2.25 (1.87-2.69) | <0.001 |

| Endocarditis | 0.91 (0.27-3.04) | 0.881 | 2.18 (1.56-3.04) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.15 (1.26-7.87) | 0.014 | 1.24 (0.96-1.60) | 0.100 |

| Aspirin use | 1.73 (0.91-3.28) | 0.096 | 0.70 (0.58-0.83) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin use | 0.70 (0.26-1.89) | 0.484 | 0.71 (0.54-0.93) | 0.012 |

| NRTI use | 1.19 (0.51-2.79) | 0.681 | N/A | N/A |

| NNRTI use | 0.38 (0.19-0.76) | 0.006 | N/A | N/A |

| PI use | 0.63 (0.30-1.33) | 0.226 | N/A | N/A |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3)* | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) | 0.477 | N/A | N/A |

| HIV RNA (copies/ml)† | 1.10 (1.04-1.17) | 0.001 | N/A | N/A |

| CNS infection/malignancy | 2.75 (1.26-6.03) | 0.011 | N/A | N/A |

Abbreviations: HR = hazard ratio; NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI = protease inhibitor; CNS = central nervous system.

CD4 cell count nadir expressed in increments of 50.

HIV RNA expressed as log value of continuous variable.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed investigating the effects of dyslipidemia on stroke risk. In the overall model, dyslipidemia alone (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.12-1.46, P<0.001) was associated with increased stroke risk. In a model with HIV added, both HIV status (HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.14-1.65, P=0.001) and dyslipidemia (HR 1.26 95% CI 1.10-1.44, P=0.001) were independently associated with increased stroke risk. Among females, dyslipidemia alone was associated with increased stroke risk (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.26-2.17, P<0.001) but was not significantly associated with stroke when age was added (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.76-1.34, P=0.93). Among males, dyslipidemia alone was not significantly associated with stroke (HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.94-1.27, P=0.27) but was associated with decreased stroke risk when age was added (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.72-0.98, P=0.029).

In a separate sensitivity analysis, statin use was associated with decreased stroke risk when included in the overall model (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.65-0.93, P=0.005) and in the HIV-only model (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.18-1.03, P=0.059). There was no interaction between statin use and dyslipidemia with respect to stroke risk in the analysis.

Discussion

We observed higher stroke rates among HIV-infected patients compared to non HIV-infected patients in a large clinical care observational cohort in an era of combination ART use, following more than 4,000 HIV-infected patients for over 25,000 person years. Our data suggest that HIV is an independent predictor of ischemic stroke, after adjusting for known stroke risk factors. The increase in stroke risk was most pronounced in HIV-infected women and in younger age groups. Furthermore, within HIV-infected patients, stroke risk was increased in association with increasing viral load, suggesting that poorer virologic control and its inflammatory and immunologic sequelae may increase cerebrovascular risk.

There are only limited studies of stroke in HIV patients. Much of our understanding of the natural history of cerebrovascular disease in patients with HIV infection stems from case reports and retrospective studies of patients with advanced disease and severe immunosuppression,[6, 15, 16] many before the widespread use of ART.[5, 7] Cerebrovascular events in these early studies were frequently attributable to concomitant opportunistic infections, lymphoproliferative disorders and other malignancies, endocarditis, or cardiomyopathy. Previous estimates of the prevalence of stroke in HIV-infected patients, ranging from 4 to 30%, originate from autopsy studies of patients dying from AIDS.[17-21] More recent estimates range from an annual incidence of 216 transient ischemic events and strokes per 100,000 population[22] to 166 ischemic strokes per 100,000 patient-years.[10] Most recently a Danish study compared rates of a broad cerebrovascular endpoint in HIV patients versus a population-based control group and found rates to be increased in the HIV group, with rate ratios similar to those found in the present study.[9] Risk was increased in patients both with and without vascular risk factors; however, multivariate modeling including vascular risk factors such as smoking as well as HIV-related factors was not performed. Our data advance this understanding by investigating stroke rates in an HIV cohort over a period of widespread ART use, using a validated, specific endpoint definition, adjusting for individual stroke risk factors including smoking, and investigating the association of stroke with clinical stage of HIV infection and with specific ART classes.

Our data demonstrate overall stroke rates of 5.27 per 1000 PY in HIV versus 3.75 in non-HIV patients, for a hazard ratio of 1.40. Overall stroke rates were comparable to established rates for the general population.[23, 24] The hazard ratio was attenuated in part accounting for traditional stroke risk factors consistent with the conclusion that these risk factors play a role in the pathogenesis of stroke in the HIV population. In particular, smoking and hypertension were risk factors that were more highly prevalent among the HIV population and significantly associated with stroke in the fully adjusted model. Our data suggest that these risk factors might therefore be particularly targeted for intervention in the HIV population.

While traditional stroke risk factors are likely to play a role in HIV-related stroke risk, HIV remained an independent predictor of stroke after adjustment for these factors. Taken together with the increased stroke rate seen in association with increasing viral load among the HIV group, these data suggest that stroke risk in the HIV population is attributable, in part, to factors other than known traditional vascular risk factors. Hypotheses to explain this excess risk include inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and macrophage activation. Inflammation underlies the pathogenesis, progression and complications of atherosclerosis.[25] HIV itself, independent of ART use, has been shown to induce endothelial dysfunction, an early marker of atherosclerosis,[26, 27] and multiple studies have demonstrated increased levels of inflammatory markers in HIV-infected patients.[28] Moreover, an immune-mediated prothrombotic state with elevated d-dimer,[29] tissue plasminogen activator antigen, and plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1, markers of impaired fibrinolysis associated with risk of CHD, may also confer stroke risk.[30, 31] Macrophage activation, seen even among those with well-controlled infection and recently associated with non-calcified plaque, may also play a role in the premature development of atherosclerosis.[32]

Gender-specific analyses revealed a striking increase in ischemic stroke risk in HIV-infected women compared to non-HIV controls. Importantly, the study included sufficient data on women, who represented 36% of the total person years. Prior studies have demonstrated a greater relative risk of myocardial infarction in women comparing HIV-infected to HIV-uninfected patients.[3, 4] This study shows a similar gender effect for stroke, which may be due in part to a lower baseline risk for stroke in women, amplifying the relative impact of an HIV-specific effect in this gender. The increased relative risk of ischemic stroke in HIV-infected women may also be explained by increased use of oral contraception or hormone replacement therapy among HIV-infected women; relatively greater differences in rates of traditional stroke risk factors including abdominal adiposity and inflammation;[33, 34] differing efficacy of stroke prevention measures by gender;[35] or lower rates of stroke risk factor modification in women due to perception of lower risk by physician[36] or patient.[37, 38] Relatively increased stroke rates in HIV-infected women may also be explained by higher levels of immune activation compared to HIV-infected men after accounting for HIV RNA level.[39]

The increased risk of ischemic stroke in the HIV cohort was limited to younger age groups (18-49 years). A similar pattern was seen in a retrospective analysis of coronary heart disease (CHD) in HIV-infected patients using California Medicaid claims data.[1] The effect of HIV on stroke may be more pronounced in younger patients before traditional age-related vascular risk factors begin to play a major role in the development of clinically apparent ischemic stroke, as CVD risk is generally very low in apparently healthy young people. The observed increase in stroke risk in younger age groups identifies an obvious need to determine the etiology of increased strokes among young HIV-infected patients and underscores the need for early identification of those at risk accompanied by appropriate risk factor modification.

Within the HIV-infected cohort, higher viral load was associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Previous studies have linked viral load to subclinical atherosclerosis[40] and endothelial dysfunction,[41, 42] and patients treated with interrupted ART in the SMART trial had higher rates of cardiovascular events.[29] Likewise, lower CD4 count has been associated with increased subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and progression of disease[43, 44] and to increased rates of cardiovascular events.[45, 46] Higher viral load and lower CD4 count may serve as surrogate markers for chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction which have been hypothesized to confer increased vascular risk. Conversely, being virologically suppressed for an extended time period might decrease vascular risk. In this study, longer duration of ART within the HIV cohort was associated with a decreased risk of stroke. Consistent with our data, shorter duration of any ART use has been shown to be an independent predictor of ischemic cerebrovascular events,[10] and improvement in intracranial vessel stenoses has been shown to occur six months following ART initiation.[15]

The use of NNRTIs at any point in time was found to be associated with a decreased risk of ischemic stroke risk. In contrast to PIs and NRTIs which have been shown to confer increased risk of CVD in previous studies,[47, 48] no consistent association between NNRTI use and risk of CVD has been identified. NNRTIs have been specifically linked to an improved lipid risk profile and elevation of HDL, an association which may help to explain the protective effect of this class of drugs. When represented as duration of medication use, however, NNRTIs were not associated with decreased stroke risk. Medication data in clinical care cohorts is subject to confounding by indication, although one would expect preferential use of NNRTIs in patients at high vascular risk (by clinicians who avoid the PI class) to lead to increased rather than decreased stroke risk.

Our study was limited by our necessary reliance on ICD codes to establish diagnoses of outcome and covariates. To strengthen the reliability of these data, we conducted a rigorous validation study to maximize sensitivity and specificity of codes for ischemic stroke. Importantly, the overall rates of ischemic stroke in our non-HIV reference group are comparable to those published from large population-based cohorts.[23, 24] In our study, data on certain stroke risk factors, such as intravenous drug use (IVDU), were not available for the majority of the patients in the cohort. However, IVDU was not thought to be appropriate for inclusion in the primary analyses due to its potential for collinearity with valvular heart disease and endocarditis. Importantly, we were able to include data on smoking – a known major stroke risk factor – through use of a novel natural language processing tool to extract smoking data from free text notes.

As the HIV population ages, chronic diseases, particularly those of a vascular nature, have become increasingly clinically relevant. We demonstrate the novel finding that stroke risk is increased for HIV patients relative to control patients and that this risk persists in part after accounting for traditional stroke risk factors. Furthermore, we show that increased stroke risk is driven, in large part, by events in women and young patients. The demonstrated association between HIV and stroke should prompt medical providers to view HIV as a risk factor for stroke and to have a low threshold to aggressively modify vascular risk, particularly in women and the young – groups not typically identified as high-risk. Long-term prospective studies with HIV-negative controls are necessary to further elucidate the interaction of chronic HIV infection, ART, and traditional vascular risk factors and their effect on the risk of cerebrovascular disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Shawn Murphy, MD, PhD (Massachusetts General Hospital Laboratory of Computer Science) and the Partners HealthCare Research Patient Data Registry group for facilitating use of their database and natural language processing tool.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant numbers 5T32MH090847 (FCC) and K01 AI073109 (VAT)

References

- 1.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, et al. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:506–512. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein D, Hurley LB, Quesenberry CP, Jr., Sidney S. Do protease inhibitors increase the risk for coronary heart disease in patients with HIV-1 infection? Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2002;30:471–477. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200208150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS. 2010;24:1228–1230. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339192f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger JR, Harris JO, Gregorios J, Norenberg M. Cerebrovascular disease in AIDS: a case-control study. AIDS. 1990;4:239–244. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole JW, Pinto AN, Hebel JR, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and the risk of stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:51–56. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000105393.57853.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engstrom JW, Lowenstein DH, Bredesen DE. Cerebral infarctions and transient neurologic deficits associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1989;86:528–532. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ovbiagele B, Nath A. Increasing incidence of ischemic stroke in patients with HIV infection. Neurology. 2011;76:444–450. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820a0cfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmussen LD, Engsig FN, Christensen H, et al. Risk of cerebrovascular events in persons with and without HIV: a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. AIDS. 2011;25:1637–1646. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283493fb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corral I, Quereda C, Moreno A, et al. Cerebrovascular ischemic events in HIV-1-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence and risk factors. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:559–563. doi: 10.1159/000214219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ances BM, Bhatt A, Vaida F, et al. Role of metabolic syndrome components in human immunodeficiency virus-associated stroke. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:249–256. doi: 10.1080/13550280902962443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng QT, Goryachev S, Weiss S, Sordo M, Murphy SN, Lazarus R. Extracting principal diagnosis, co-morbidity and smoking status for asthma research: evaluation of a natural language processing system. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhagavati S, Choi J. Rapidly progressive cerebrovascular stenosis and recurrent strokes followed by improvement in HIV vasculopathy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:449–452. doi: 10.1159/000157632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tipping B, de Villiers L, Wainwright H, Candy S, Bryer A. Stroke in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2007;78:1320–1324. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.116103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anders KH, Guerra WF, Tomiyasu U, Verity MA, Vinters HV. The neuropathology of AIDS. UCLA experience and review. Am J Pathol. 1986;124:537–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizusawa H, Hirano A, Llena JF, Shintaku M. Cerebrovascular lesions in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Acta Neuropathol. 1988;76:451–457. doi: 10.1007/BF00686383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connor MD, Lammie GA, Bell JE, Warlow CP, Simmonds P, Brettle RD. Cerebral infarction in adult AIDS patients: observations from the Edinburgh HIV Autopsy Cohort. Stroke. 2000;31:2117–2126. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray F, Gherardi R, Scaravilli F. The neuropathology of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). A review. Brain. 1988;111(Pt 2):245–266. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto AN. AIDS and cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1996;27:538–543. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evers S, Nabavi D, Rahmann A, Heese C, Reichelt D, Husstedt I-W. Ischaemic cerebrovascular events in HIV infection: a cohort study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15:199–205. doi: 10.1159/000068828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carandang R, Seshadri S, Beiser A, et al. Trends in incidence, lifetime risk, severity, and 30-day mortality of stroke over the past 50 years. JAMA. 2006;296:2939–2946. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrea RE, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Hayes M, Kase CS, Wolf PA. Gender Differences in Stroke Incidence and Poststroke Disability in the Framingham Heart Study. Stroke. 2009;40:1032–1037. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francisci D, Giannini S, Baldelli F, et al. HIV type 1 infection, and not short-term HAART, induces endothelial dysfunction. AIDS. 2009;23:589–596. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328325a87c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf K, Tsakiris DA, Weber R, Erb P, Battegay M. Antiretroviral therapy reduces markers of endothelial and coagulation activation in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;185:456–462. doi: 10.1086/338572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS medicine. 2008;5:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355:2283–2296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Rabe J, et al. Increased PAI-1 and tPA antigen levels are reduced with metformin therapy in HIV-infected patients with fat redistribution and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:939–943. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johansson L, Jansson JH, Boman K, Nilsson TK, Stegmayr B, Hallmans G. Tissue plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and tissue plasminogen activator/plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 complex as risk factors for the development of a first stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2000;31:26–32. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burdo TH, Lo J, Abbara S, et al. Soluble CD163, A Novel Marker of Activated Macrophages, is Increased and Associated with Noncalcified Coronary Plaque in HIV Patients. J Inf Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir520. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadigan C, Meigs JB, Corcoran C, et al. Metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and lipodystrophy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:130–139. doi: 10.1086/317541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Towfighi A, Zheng L, Ovbiagele B. Weight of the obesity epidemic: rising stroke rates among middle-aged women in the United States. Stroke. 2010;41:1371–1375. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111:499–510. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferris A, Robertson RM, Fabunmi R, Mosca L, American Heart A, American Stroke A. American Heart Association and American Stroke Association national survey of stroke risk awareness among women. Circulation. 2005;111:1321–1326. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157745.46344.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosca L, Jones WK, King KB, Ouyang P, Redberg RF, Hill MN. Awareness, perception, and knowledge of heart disease risk and prevention among women in the United States. American Heart Association Women’s Heart Disease and Stroke Campaign Task Force. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:506–515. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meier A, Chang JJ, Chan ES, et al. Sex differences in the Toll-like receptor-mediated response of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to HIV-1. Nat Med. 2009;15:955–959. doi: 10.1038/nm.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangili A, Jacobson DL, Gerrior J, Polak JF, Gorbach SL, Wanke CA. Metabolic syndrome and subclinical atherosclerosis in patients infected with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1368–1374. doi: 10.1086/516616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blum A, Hadas V, Burke M, Yust I, Kessler A. Viral load of the human immunodeficiency virus could be an independent risk factor for endothelial dysfunction. Clinical cardiology. 2005;28:149–153. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960280311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solages A, Vita JA, Thornton DJ, et al. Endothelial function in HIV-infected persons. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006;42:1325–1332. doi: 10.1086/503261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsue PY, Lo JC, Franklin A, et al. Progression of atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness in patients with HIV infection. Circulation. 2004;109:1603–1608. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124480.32233.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Gange SJ, et al. Low CD4+ T-cell count as a major atherosclerosis risk factor in HIV-infected women and men. AIDS. 2008;22:1615–1624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328300581d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Buchacz K, et al. Low CD4+ T cell count is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease events in the HIV outpatient study. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51:435–447. doi: 10.1086/655144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Triant VA, Regan S, Lee H, Sax PE, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK. Association of immunologic and virologic factors with myocardial infarction rates in a US healthcare system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:615–619. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f4b752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, et al. Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:1723–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R, et al. Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet. 2008;371:1417–1426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60423-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]