Abstract

The epidemiology of HIV infection in the US in general, and in the southeast, in particular, has shifted dramatically over the past two decades, increasingly affecting women and minorities. The site for our intervention was an infectious diseases clinic based at a university hospital serving over 1,300 HIV-infected patients in North Carolina. Our patient population is diverse and reflects the trends seen more broadly in the epidemic in the southeast and in North Carolina. Practicing safer sex is a complex behavior with multiple determinants that vary by individual and social context. A comprehensive intervention that is client-centered and can be tailored to each individual’s circumstances is more likely to be effective at reducing risky behaviors among clients such as ours than are more confrontational or standardized prevention messages. One potential approach to improving safer sex practices among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) is Motivational Interviewing (MI), a non-judgmental, client-centered but directive counseling style. Below, we describe: (1) the development of the Start Talking About Risks (STAR) MI-based safer sex counseling program for PLWHA at our clinic site; (2) the intervention itself; and (3) lessons learned from implementing the intervention.

Keywords: HIV prevention, Motivational interviewing, Sexual behavior

Background

The southeastern United States has the highest overall reported incidence of HIV infection in the US. The epidemiology of HIV infection in the US in general, and in the southeast, in particular, has shifted dramatically over the past two decades, increasingly affecting women and minorities. From 2000 to 2003, 28% of new HIV cases in the US overall were among women; 36% of all newly infected persons were infected through heterosexual sex. Only 44% of the new cases occurred among men who have sex with men. Among newly infected women, 78% were infected through heterosexual sex; 19% through intravenous drug use. The annual rate of new HIV infections has also increased among minority populations relative to the incidence among whites (CDC, 2003; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002; Group SSASDW, 2003; Hader, Smith, Moore, & Holmberg, 2001; Holmes et al., 1997), particularly in the southeastern US (NC-DHHS, Epidemiology and Special Studies Unit, 2006). HIV surveillance data from North Carolina, indicate that African Americans experience HIV infection incidence rates approximately eightfold higher than those seen for whites; the rates among African American women are 15–17-fold higher than among white women (NC-DHHS, Epidemiology and Special Studies Unit, 2006). Furthermore, studies suggest that economic and health disparities contribute to the higher HIV incidence among ethnic minorities and women in the southeastern US (Adimora et al., 2006; Adimora & Schoenbach, 2005; MMWR, 2005).

The site for our intervention was an Infectious Diseases clinic based at a university hospital in North Carolina. Currently, 1,300 HIV-infected patients are seen at our site each year from throughout central and southeastern urban and rural areas of North Carolina. Our patient population is diverse and reflects the trends seen more broadly in the epidemic in the southeast and in North Carolina. According to descriptive data from the UNC Center for AIDS Research HIV Cohort (Napravnik et al., 2005), one-third of our clinic population is female and 61% are African American. Fifty percent of all patients at our site became infected through heterosexual transmission; 25% are men who have sex with men. Most clients receive either Medicaid, Medicare, or have no health insurance coverage and many are low literate and disenfranchised. Seventy percent have a history of (non-intravenous) substance use, mental illness or both. Results from surveys of patients at our site demonstrating that a majority of patients, whether they had one or multiple partners, engaged in unprotected intercourse (Napravnik et al., 2002, Strauss et al., 2001) raised concerns that a program to promote safer sexual activities among was needed. These observations led our HIV clinic staff to seek the initiation of HIV prevention programs for their clients.

Rationale for a Motivational Interviewing-Based Intervention

Practicing safer sex is a complex behavior with multiple determinants that varies by individual and social context, particularly among a diverse group of people, many of whom are impoverished and have a history of substance abuse (Baele, Dusseldorp, & Maes, 2001; Fisher, Willcuts, Misovich, & Weinstein, 1998; Kalichman, Kelly, Morgan, & Rompa, 1997a; Kalichman, Roffman, Picciano, & Bolan, 1997b; Kalichman, Nachimson, Cherry, & Williams, 1998; Reitman et al., 1996; Remien, Carballo-Dieguez, & Wagner, 1995; Rotheram-Borus, Reid, Rosario, & Kasen, 1995). A comprehensive intervention that can be tailored to each individual’s circumstances is more likely to be effective at reducing risky behaviors among clients such as ours than are more confrontational or standardized prevention messages (Adamian, Golin, Shain, & DeVellis, 2004; Golin, Earp, Tien, Stewart, & Howie, 2006; Kalichman, 2005; Strang, McCambridge, Platts, & Groves, 2004; Carey et al., 1997). One potential approach to improving safer sex practices among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) is Motivational Interviewing (MI), a non-judgmental, client-centered but directive counseling style. MI has been shown to be particularly effective for patients who have histories of substance abuse (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003; Diorio et al.,2003; Dunn, Deroo, & Rivara, 2001; Emmons & Rollnick, 2001; Strang et al., 2004) and may be a promising approach to safer sex counseling for HIV-infected clients at our site for whom substance abuse is a strong risk factor for practicing unsafe sex.

The MI principles are based upon the idea that the client–counselor relationship is a partnership (Dunn et al.,2001; Emmons & Rollnick, 2001; Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Rollnick, 2001) and that avoidance of confrontation increases a client’s intrinsic motivation and confidence to change behavior (Emmons & Rollnick, 2001; Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

The MI is based on the premise that clients feel ambivalent about unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking, problem drinking or having unsafe sex (Dunn et al., 2001; Emmons & Rollnick, 2001; Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Rollnick, 2001). The counselor emphasizes the client’s autonomy and guides him or her toward positive behavior changes using goals that the client identifies as salient (Emmons & Rollnick, 2001). MI includes five principles aimed at helping clients resolve ambivalence: (1) expressing empathy; (2) avoiding argument; (3) rolling with resistance; (4) developing discrepancy; and (5) supporting self-efficacy (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The counselor expresses empathy by using techniques from Rogerian psychology, such as reflective listening, to help clients feel understood and to raise their awareness of the ambivalence they feel about particular behaviors ((Dunn et al., 2001; Emmons & Rollnick, 2001; Rollnick, 2001; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Counselors help clients become aware of discrepancies that exist between clients’ values and behaviors to lead them to make self-motivating statements about their intrinsic desire to change their behavior (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Finally, the counselor uses specific techniques to build the client’s self-efficacy, or confidence, to make a change, such as helping him or her to identify strategies to overcome barriers and enhance facilitators to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Motivational Interviewing has been used effectively to improve a range of health behaviors, including safer sex practices, albeit among HIV-negative persons (Belcher et al., 1998; Picciano, Roffman, Kalichman, Rutledge, & Berghuis, 2001; Reitman et al., 1996). Three of five studies that tested MI interventions addressing risky sexual practices of HIV negative people (Baker, Healther, Wodak, Dixon, & Holt, 1993; Baker, Kochan, Dixon, Heather, & Wodak, 1994; Belcher et al., 1998; Picciano et al., 2001; Reitman et al., 1996) found significantly improved condom use and/or a decrease in unprotected sexual intercourse compared with controls. Brief, MI-style interventions have been used successfully among patients with HIV, but primarily to improve antiretroviral treatment (ART) adherence (Adamian et al., 2004; Diorio et al., 2003; Golin et al., 2006; Safren et al., 2001). In addition, group level safer sex interventions that targeted self-efficacy and motivation (Kalichman et al. 2001; Wingood et al., 2004), successfully improved HIV-infected persons’ safer sex practices. Given the success of MI and of “prevention with positives” group interventions that used an approach consistent with MI among clients similar to ours, we believed that developing safer sex interventions based on MI for our HIV clinic population was likely to be successful. Individual MI sessions, however, seemed better suited to our site, since a large proportion of patients travel long distances to the clinic and face considerable transportation barriers. Thus, an intervention that depends upon scheduling groups of patients to come regularly to the same location at the same time would not be feasible or successful at our site.

We previously developed and delivered a standardized, two-session MI ART adherence program, called Participating and Communicating Together (PACT), that was comfortable for our clients and showed a trend toward improving ART adherence among our clients (Adamian et al., 2004; Golin et al., 2006; Thrasher, Golin, Earp, Porter, & Tien, 2006). A number of elements remained in place for delivering MI to clients at our site. Hence, we had existing expertise and infrastructure upon which we could draw to develop a safer sex MI counseling program described below.

In this paper, we describe: (1) the development of the Start Talking About Risks (STAR) MI-based safer sex counseling program for PLWHA at our clinic site; (2) the intervention itself; and (3) lessons learned after a year of implementing the intervention.

Development of the MI-Based Safer Sex Intervention

We developed a new program targeting safer sex practices based on: (1) the existing infrastructure and experiences from the previous MI-based program; (2) a literature review and development of a conceptual model of factors influencing safer sex practices; and (3) results of formative research. While the general approach of the MI adherence protocol remained the same, we made changes to both the delivery and content of the intervention to adapt it to address safer sex.

Existing Infrastructure and Prior Experience with Delivering MI-based Interventions

One of the investigators (CEG) was a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT), an international organization of members who have undergone “train the trainer” instruction in MI. She also had experience conducting standardized initial and booster MI trainings during implementation of the MI-based adherence program. Second, we had developed and tested a seven-step standardized protocol to administer each adherence MI session (Adamian et al., 2004; Golin et al., 2006; Thrasher et al., 2006). This protocol is not a specific script, but rather a guide that the counselor uses to walk the client through a series of steps or exercises. Third, existing administrative systems for enrolling and tracking clients undergoing monthly MI sessions remained available to us for our safer sex program.

For the treatment adherence program, we had developed standardized quality assurance methods to maintain intervention fidelity and quality. Specifically, we possessed prior knowledge and experience in the following areas: (1) audio-taping and coding MI sessions to assess the quality of client–counselor interactions using the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC 2.0) System; and (2) using standardized data recording sheets to document the content of each MI session. These systems demonstrated our MI counselors’ abilities to meet MI quality benchmarks and maintain fidelity to the MI protocol using ongoing training and feedback (Thrasher et al., 2006).

The STAR evolved out of a growing interest among clinic staff and providers in implementing programs to address the social services and HIV prevention needs of their patients. Consequently, we hired an individual with a Masters in Social Work to fill one position with two roles: STAR program MI counselor and the prevention specialist for the clinic to whom medical providers referred high-risk HIV patients for traditional (non-MI-based) prevention counseling. This facilitated her integration into the clinic staff, culture, and routine. Sharing in the cost of her salary with the clinic to cover other clinic duties made having an MI counselor in the clinic more efficient and feasible.

Use of Literature Review and Conceptual Model to Inform Intervention Development

We first conducted an extensive literature review of factors that influence safer sex practices among PLWHA. Those factors have been conceptualized within three broad categories: (1) patient characteristics—cognitive, emotional, attitudinal, skills, coping, and self-efficacy (Kalichman et al., 1998; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1995); (2) features of sexual relationships—number, concurrency, duration, type, serostatus concordance (Robinson, Bockting, Rosser, Miner, & Coleman, 2002); and (3) socio-environmental factors—peer norms, social support, stigma, socioeconomic factors, and concurrent substance abuse (Kalichman et al., 1998).

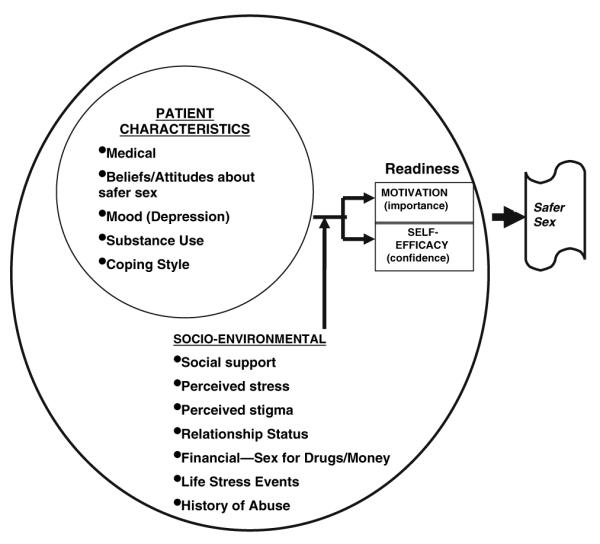

We developed a conceptual model (Fig. 1) integrating the factors that influence risky sexual behavior of PLWHA described above (Fishbein & Yzer, 2003) with concepts from Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986) and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Accordingly, we conceptualized “adherence to safer sex practices” as influenced most proximally by patients’ motivation and self-efficacy to carry out activities required to avoid unprotected intercourse. We used this conceptual model to design the MI program to address the mutable, psychosocial variables that have an impact on risky sexual behavior. We sought to address those variables by: (1) raising clients’ awareness of their relative levels of motivation and self-efficacy; (2) identifying factors that inhibit and enhance motivation and self-efficacy; (3) developing strategies to overcome identified barriers and enhance facilitators (Adamian et al., 2004; Golin, Patel, Paulovits, & Quinlivan, 2005). Motivation is enhanced through targeting cognitive and attitudinal factors (knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about safer sex, sexual self-esteem). Self-efficacy is addressed by targeting social support and peer normative support, perceived stigma, coping style, problem solving, condom use, and communication skills. The influence of relationship and situational factors as moderators of these associations was considered as well. This approach allowed the counselor to target known barriers yet permitted a highly individualized application of a sexual behavior model by ascertaining specific obstacles to changing behavior.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of factors influencing performance of three safer sexual behaviors

Formative Research to Inform Intervention Development

We conducted qualitative interviews with 20 clients at our site who were representative of the ethnic make-up of our clinic. We analyzed the interviews with AtlasTi qualitative analysis software, using grounded theory methodology (Miles & Huberman, 1994) to assess patients’ needs and preferences for safer sex counseling. Five main themes emerged from our analysis. First, patients perceived many barriers and facilitators to practicing safer sex, including the availability and affordability of condoms, social support, sensation loss and discomfort due to condom use, latex allergies, alcohol and other drug use, lack of disclosure of one’s HIV status, concerns about getting STIs or reinfection with other strains of HIV, and aspects of intimate relationships that influenced safer sex choices. One participant put it this way, “I think you have to have them handy. If you’re going to be in a sexual situation that’s going to be pre-meditated, you need to be prepared. You better have condoms or they better have condoms.” Several participants mentioned three aspects of their intimate relationships that influenced their safer sex choices: The relationship between intimacy and safer sex choices; their strong desires to protect partners; and their fears of being rejected by partners as a result of revealing their serostatus. One participant expressed the following, “Not knowing how they’re going to react. And if you really, really like the person, then you are worried that if you tell them you’re going to lose them and you’ll be alone again.”

A second theme showed that participants were very interested in having a safer sex counseling program based in the clinic. Participants mentioned a number of topics they would like to see included in such a program, including: Information about HIV transmission, safe and unsafe sexual activities, counseling about ways to disclose one’s HIV status, information about STIs and HIV re-infection, and abstinence.

Third, participants felt it was important that safer sex programs for PLWHA have a “sex positive” rather than punitive message. Participants expressed concerns that, if not approached with a message that “one can have a satisfying sex life while practicing safer sex,” a “prevention with positives” program could increase HIV-associated stigma. Fourth, participants said that while they would prefer to have their doctor provide safer sex counseling because of their pre-existing relationships, they were open to having a prevention counselor if they could develop a trusting relationship with that person. Finally, participants expressed the need for a program that was realistic and provided substantive advice in language that was culturally appropriate. As one participant put it,”…if it is short in choices and not real, then it will not work. It will be a white elephant. Everyone comes in and sees it, but [they] don’t get anything from it.”

Modifications to MI Delivery

Based on prior experience with the adherence program, our literature review, and formative work, we made a number of changes regarding MI delivery. First, because the ART adherence program had a moderate effect on medication adherence, we added a third session, so that the MI program was more intensive and made modifications to the first session protocol to enhance rapport-building. Second, to ensure that counselors had better counseling skills, we required the safer sex MI counselor to have a Master’s level degree in counseling. We also added a place in the protocol for the counselor to assess clients’ current sexual and intimate relationships. This was done by including questions in the protocol such as “Are you dating anyone right now?”, “Do you know your partner’s serostatus?”, “Does s/he know your status?”, “What do you and you partners like to do together to be close?” This approach not only enhanced rapport building, but also allowed the counselor to assess the client’s level of risk and relationship status.

Third, based on our conceptual model, which emphasized the independent influences of self-efficacy and motivation to change a behavior, we added an explicit menu of counseling strategies from which counselors could choose that were based on the clients’ self-rated levels of motivation and self-efficacy. Counselors asked clients to rate, first their motivation, and then their self-efficacy to carry out or change a behavior, on a scale of 0–10, with “0” being “not at all” and “10” being “extremely” “important” or “confident,” respectively. Different strategies were then offered for clients based upon their self-reported levels of self-efficacy/confidence and motivation/importance for change.

Fourth, because during formative interviews participants expressed a desire for information about a broad range of safer sex topics, we added to the protocol an option for the counselor to use the “elicit-provide-elicit” technique of MI, which allows counselors to provide information to clients after eliciting the client’s existing knowledge and obtaining their permission. To help counselors provide this information, we developed a series of standardized informational modules that counselors use to inform their clients about aspects of safer sex (described in more detail below).

Finally, during MI-based adherence sessions, a range of needs arose that were beyond the scope of the MI counselor (e.g., needs for financial counseling, substance abuse treatment, long-term psychotherapy, domestic violence support, etc.). Therefore, we added an explicit referral step to the revised protocol. Because substance abuse was frequently raised as a barrier to practicing safer sex in formative interviews, we designed the program to allow counselors to address substance abuse as a barrier to practicing safer sex, by including it as a topic in the program menu. Participants requesting substance abuse treatment are referred for those services while the safer sex issues are addressed in our program.

Modifications to the Content Delivered During MI Sessions

We replaced didactic lectures about ART adherence in the MI training with those related to safer sex practices, including teaching about factors affecting safer sex practices of PLWHA, human sexuality, and practical information about HIV transmission, and use of barrier methods. Based on results of formative interviews, we also trained counselors to emphasize a “sex positive” message. Lastly, we created a series of standardized informational modules (described below) that participants had requested during formative interviews. These modules were developed to be used not only as a verbal script by the counselor, but also, in the form of print materials and a computer-based educational tool. The counselor could refer the client to these materials if time did not allow them to review all the requested information in person. The informational modules were refined using input obtained from our formative interviews and in three meetings with our Community Advisory Board to make the wording, information and format relevant and culturally appropriate for our population, such as using representative photographs in the materials to reflect the clinic’s patient population diversity.

Final STAR Motivational Interviewing Program

STAR Motivational Interviewing Protocol

This section describes the STAR Safer Sex MI protocol. The STAR Program involves three consecutive monthly, ~30–40 min, one-on-one counseling sessions designed for adult HIV-infected patients receiving medical care who have been sexually active within the last 6 months. The MI protocol is used by a counselor as a guide to deliver the sessions and to help walk him or her through a series of 13 steps to assess the topic to discuss, clients’ motivation and confidence to change and ultimately toward setting a goal for change. As described above (Modifications to MI Delivery), the counselor tailors the session to clients’ self-reported levels of motivation and self-efficacy. Although the counselor does not conduct a session with a pre-set target for reducing risky sexual behavior, often these conversations lead clients to become aware of the ambivalence they feel about less safe sexual behavior, which may raise their awareness of an intrinsic motivation to change. The guide includes the option of using the standardized informational modules described above. All three sessions use the same 13 steps but some steps vary based on whether it is the first, second, or last session. For example, the first session places a greater emphasis on rapport-building and assessment whereas the last session emphasizes closure.

STAR Motivational Interviewing Counselors and Training

The STAR program was administered by an individual who: (1) has a Master’s level degree in a social work with an emphasis on counseling; (2) underwent a 2.5 days training by the state health department in HIV counseling and testing; and (3) underwent the training described below. While we chose an MSW to deliver the intervention in this trial to maximize the likelihood of achieving an effect, the training manual is designed in a manner that can be implemented by staff or peers who have received some prior counseling training but are less skilled in counseling than the MSW.

We developed a standardized 150-page manual to guide the STAR training program. The STAR training is designed to be conducted by a member of the MINT. Such trainers (and instructional programs to become a trainer) are available through the website http://www.motivationalinterviewing.org. The training incorporates didactic information (human sexuality, safer sex practices, sexual negotiation, background information about MI, and information about resources available for referrals), video demonstrations and interactive sessions, including role playing, that teach and enhance participants’ MI and prevention counseling skills (how to open a session and develop rapport, reflective listening, addressing client resistance, and discrepancy); practicing the 13-step protocol, and a review of intervention fidelity. The manual is organized into five training days to build MI counseling skills in the context of safer sex counseling.

To maintain intervention quality and fidelity during program implementation, biweekly booster trainings were conducted in which the trainer (CEG) reviewed the MI audiotapes with the counselor to provide feedback and assess adherence to the protocol (Miller, 2000; Rollnick, Heather, & Bell, 1992).

Program Enrollment

All patients scheduled for a routine visit were screened for eligibility in the program. Clients were eligible if they were HIV-infected, aged 18 or older, had been a patient in the clinic at least 3 months, had previously consented to be approached for research studies, reported vaginal, anal or oral intercourse in the last 6 months, and had no plans to leave the clinic. The clinic screener reviewed a CFAR clinic research database to assess whether patients were eligible for the program. We approached all the scheduled patients who met these criteria to double check their eligibility and to invite them to participate in our study. After patients provided informed consent, they were randomized to either the MI-based safer sex intervention or the standard of care control arm of the study.

Quality Assurance of the STAR Program

To date, we have enrolled 148 participants, 68 of whom were randomized to receive MI. We have administered a total of 169 safer sex MI sessions to those clients. Of the 68 clients receiving MI thus far, 45 have completed all three MI sessions, 11 have completed two and 12 have completed one. Following each session, the counselor completed an MI data recording sheet to document the following: (1) the duration of the session (in minutes); (2) the topics chosen from the menu board by the client to discuss; (3) the rating (on a scale of 0–10) regarding the importance the client placed on the chosen behavior; (4) the rating (on a scale of 0–10) regarding the self-efficacy or confidence the client had to address the chosen behavior; (5) the barriers and facilitators the client identified to making a behavior change; and (6) the goals and strategies set by the client.

Characteristics of the 68 persons who participated in at least one of the MI sessions are summarized in Table 1. The mean session length was 34.4 min (range 20–90 min). Patients chose to talk about a range of topics (Table 2). Table 2 shows the percentage of people who selected each topic to discuss. In 23 post-counseling phone interviews that we conducted to assess patients’ experiences and satisfaction with the program, the vast majority reported feeling “very comfortable” with the counseling sessions, 100% felt the counselor understood them “a lot.” Eighty percent said they related a lot to the menu of topics offered, and nearly half believed they were “very likely to change” due to the MI. In open-ended questions, clients consistently reported that they felt “respected” and “really listened to” about topics that were salient to them (Golin et al., 2005).

Table 1.

Characteristics of motivational interviewing participants (N = 68)

| Variable | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 43.6 (SD 7.41; range | 29–67; median 43) |

| N | Percent | |

| Female gender | 29 | 43 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 46 | 67 |

| Caucasian | 17 | 25 |

| Other | 5 | 8 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight/heterosexual | 44 | 65 |

| Gay/homosexual | 16 | 23 |

| Bisexual | 6 | 9 |

| Other | 2 | 3 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single/never married | 27 | 40 |

| In a committed relationship (but not married and not living together) |

3 | 4.5 |

| In a domestic partnership (living with a committed partner) |

11 | 16 |

| Married | 14 | 20.5 |

| Separated | 3 | 4.5 |

| Divorced | 5 | 7 |

| Widowed | 2 | 3 |

| Other | 3 | 4.5 |

Table 2.

Main topic chosen for discussion by all study participants (N = 169 sessions)

| Topic chosen | Specific issues client raised | Number choosing topic N (%) N = 169 sessions |

|---|---|---|

| Condom use | How to use condoms | 50 (30%) |

| Overcoming barriers to condom use (e.g., keeping them nearby, buying them ahead of time, using lubrication to increase sensation) |

||

| Condoms make people feel dirty | ||

| People like to “feel” their partner | ||

| Heat of the moment | ||

| Alcohol/other drug use | Discussion of how drugs and alcohol impede safer sex practices |

27 (16%) |

| Keeping self and others safe from re-infection and STI’s (usually among concordant couples or partners of unknown status) |

Keeping self-safe from STIs | 24 (14%) |

| Keeping one’s partner safe from STI’s | ||

| Re-infection | ||

| Risk of resistance | ||

| Could make one-another sicker | ||

| Karma | ||

| Relationships | Everyone wants someone | 23 (13.5%) |

| Maintaining boundaries | Not just sex, dinner, movie | |

| Time invested in relationship | ||

| Future relationships | Love | |

| Feeling safe in relationships | Likes security of relationship | |

| Remaining monogamous | If did not have relationship would probably “be on streets” |

|

| Does not want to be alone | ||

| Communication with partner | How to say “no” | |

| Maintaining relationship | Asking for what one wants out of partner | |

| Keeping partner negative | Love for partner | 17 (10%) |

| Partner has stood by them | ||

| Do not want partner to go through what they have | ||

| Disclosure | Self-care | 8 (4.5%) |

| Alternate ways to be intimate (not here) | ||

| Disclosure of serostatus to partners | ||

| Self-esteem issues | ||

| Re-disclosure | ||

| Stigma | ||

| Ignorance | ||

| They have a right to know what they are getting into | ||

| Self-care includes | Wanting to stay on same medication | 6 (3.5%) |

| Learning to say no Taking time for self Taking meds |

If no time for self then may use AOD then will not practice safer sex |

|

| Risk assessment | Pt. did not pick topic | 6 (3.5%) |

| Alternate ways to be intimate | Pt. unable to engage in certain sexual acts because of health issues |

4 (2%) |

| Fear alternate ways will not please partner | ||

| Desire to please partner | ||

| Fear of harming partner | ||

| Worries about getting a STI | Does not want another STI | 3 (2%) |

| HIV only STI | ||

| Another STI could make HIV worse | ||

| STI’s make people look sick | ||

| Patient update | Pt. in and out of hospital, extremely ill. Not appropriate to discuss sex; fear of ruining relationship with pt. did discuss later |

1 (0.5%) |

Implementation of the STAR Program: Challenges, Successes, and Lessons Learned

We chose to implement an individual-level MI-based safer sex intervention appropriate for the diverse group of, often disenfranchised clients we serve. While clients’ responses to the program were generally very positive, we learned a number of lessons during implementation. These lessons fell broadly into three areas; recruitment and retention of clients in the program, the logistics of delivering the intervention in a medical setting, and implementation of the MI protocol.

Recruitment and Retention to the STAR Program

Most of our clients were poor and many were rural. Nearly half of the patients at our clinic travel over 60 miles to come for medical care and many have limited financial resources for transportation. Some clients do not own a car and rely on a medical van (which cannot be used for research visits because of Medicaid funding regulations) to bring them to their medical appointments. For these reasons, we tried to align the monthly MI visits with medical visits. However, this was not always possible because most routine medical visits occurred every 3 months.

In designing the program, we had anticipated that transportation barriers would hinder patients’ willingness to enroll. Therefore, from the outset, we offered $15.00 incentives for each MI session attended. While the availability of incentives seemed to enhance recruitment, we found that transportation barriers still hindered people’s abilities to come to follow-up visits on schedule. As a result, we sought to enhance follow-up during the study by making the MI schedule more flexible, allowing clients to remain in the program even when they came back for their second and third MI visits outside of the month-long intervals (for up to 6 months from the baseline visit).

We also provided up to $15.00 in gas money to participants who experienced travel hardship and up to $2.00 in parking vouchers to participants who drove and parked their vehicles in the hospital pay parking lot for their MI sessions. Using this approach, we achieved an 80% retention rate. We are aware that with this approach we may be affecting the effectiveness of the intervention by allowing longer intervals between MI sessions for some clients. However, no studies have assessed the relative effectiveness of different time intervals between MI sessions to confirm or refute our impressions.

In the future, considering that several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of phone-delivered MI (safer sex counseling included) (McKee, Picciano, Roffman, Swanson, & Kalichman, 2006; Resnicow et al.,2001), offering the option of having their second MI session over the phone may help some clients who live far away maintain continuity with the MI-based safer sex program. However, many of the patients who had the greatest barriers to returning for MI sessions were also the hardest to follow and contact by phone; many had disconnected phone numbers. Our provision of $15.00 to assist clients with transportation costs and $5.00 in meal vouchers may have distorted their feelings about the MI and may limit the ability to replicate the STAR program cost-effectively. However, the provision of transportation money was used to supplement the lack of normal transportation assistance resources that would have been available to many clients if they had not been receiving the MI counseling in the context of a research study.

Although our program delivery and evaluation are not complete, our experience to date indicates that clients would like to have had at least one more MI session. We prepared clients for closure by informing them of the number of MI sessions, but some clients seemed to have trouble ending the MI program and expressed disappointment at having to end their last session. Therefore, while we did not have the resources to add additional MI sessions, we modified the protocol to augment preparing clients for closure. The counselor took more time to remind clients at each visit the number of sessions remaining, acknowledged potential feelings the client might have had about closure, and encouraged discussion of those feelings. This approach facilitated clients to use the time they had to more fully address issues they raised. Where needed, the counselor also sought mental health referrals.

Program Logistics in a Clinic Setting

We faced a number of very practical challenges to integrating STAR into the practices of a busy medical clinic. For example, in order to schedule rooms in the clinic where the MI could be conducted, the counselor needed to be in frequent communication with clinic staff throughout the day. Similarly, we learned that it was important to communicate with each client’s nurse and doctor about what other appointments and services (e.g., lab tests, pharmacist visits, etc.) clients needed during their visits so that their care was coordinated appropriately and STAR did not interfere with medical care. To facilitate integration of our program into the clinic routine, the counselor found it was helpful to attend weekly clinic staff meetings so that she was both more aware of clinic needs and perceived by other staff members as a part of the clinical staff. While available referral services were reviewed at the time of the training, during implementation the counselor gained additional knowledge of locally available referral services and developed skills at working within the medical system, such as better navigating the system and being more aware of available client services and how to access them most efficiently.

Lessons Learned About Following the MI Protocol

Although the STAR protocol was relatively easy to administer and the training generally prepared the counselor well to deliver the intervention, the review of audiotaped sessions during booster trainings, not only allowed the trainer to review the protocol and MI techniques with the counselor, but also provided a critical opportunity to fine-tune the techniques. For example, one challenge that the counselor faced was handling clients who wanted to discuss topics that represented immediate needs (such as family illness, housing, job instability, relationships with parents, etc.) that were unrelated to the safer sex topic they chose. During training, techniques were taught for bringing the discussion back to the protocol. During implementation, we learned that allowing some clients to discuss topics unrelated to their chosen topic was critical to establishing rapport, particularly in the first session. This situation often occurred with clients who had mental health needs or financial needs that were not being addressed elsewhere. Initially, the counselor felt conflicted between her need to maintain rapport with clients and her need to address safer sex practices with them. We learned to manage these situations by giving the counselor the option of allowing such clients to discuss unrelated issues in the first session at greater length than we had originally intended. The counselor also addressed these issues by making referrals, such as to mental health services. Only after the counselor felt that the client’s concerns had been acknowledged and understood did she use techniques to return the patient to the protocol. This was generally done by asking clients how they saw the issues they raised as being related to safer sex practices and reminding them of the more circumscribed goals of the STAR program. Generally, when the counselor addressed these situations in this manner, clients returned to the second MI visit much more focused on addressing their chosen safer sex topic. A counselor implementing this program outside of a study protocol, however, might have more freedom to pursue additional directions with clients as needed.

A second issue that we faced was that few clients reported multiple partners; most were in monogamous, long-term relationships. Many of these clients engaged in some unprotected sex, but the strategies for reducing risk are different from the ones used with patients who have multiple partners. Although the most frequently selected topic was “how to use a condom correctly,” it was only selected by 30% of our clients. A majority of clients chose topics that were less about the mechanics of condom use, and more about communication, relationships and self-care. Many sessions revolved around issues of empowerment and sexual negotiation. These involved helping clients understand their relationships with partners better in order to help them communicate their safer sex needs to their partners more comfortably and effectively. Also, clients wanted to discuss ways to care better for themselves and reduce the stress in their lives as an approach to reducing risky sexual practices, including reducing substance abuse. This is consistent with a previous trial by Kalichman et al. (2001) which found that stress reduction was the primary mediator of the effect of the intervention on risky sexual practices. Our experiences thus far suggest that safer sex counseling, particularly among people in primarily monogamous relationships, needs to help clients address a range of aspects of their sexual partnerships that go well beyond specific sexual practices. For example, many women mentioned poor self-esteem as a frequent barrier to being able to practice safer sex. Although they wanted to practice safer sex with their partners, these women felt powerless to influence their partners to wear a condom. The counselor helped women raise their self-efficacy to address condom use with partners using a number of strategies. Often she helped women identify other areas of their lives, such as substance abuse treatment, in which they had been strong and successful. In addition, she gave some women opportunities to role play conversations with partners in which they explained how they felt about wanting their partners to wear condoms. If interested, women were also provided with information about female condoms, dental dams, lubrication and other ways to make condoms a more appealing and comfortable part of their sexual practices. In a study by Wingood et al. (2004) of an effective safer sex intervention for HIV-infected women in the southeastern United States, gender pride was an important aspect of the intervention.

Third, some clients were unfamiliar with setting goals and required education about this process in general before addressing goal setting for sexual health. To provide this education, we developed specific strategies (including use of metaphors and analogies) to increase clients’ understanding of goals and readiness to set them. For example, rather than asking clients to set goals, the counselor would ask them to talk about their dreams or intentions for their intimate relationships. Often guiding clients to take a “hypothetical look over the fence,” to imagine their life in a different way, helped them to begin to envision the possibility of setting a specific goal to make a change.

Conclusion

Our site serves a diverse and challenging group of urban and rural patients. By interviewing 25 participants who had undergone MI by phone after their sessions, we affirmed that the use of MI in the STAR program allowed a non-judgmental, non-confrontational approach which clients reported engendered respect and collaboration. A diverse range of topics was selected by clients from the menu offered as part of the MI intervention, confirming our conceptual view that PLWHA struggle with a variety of factors in their lives which have an impact on their safer sex practices, consistent with observational studies. This report goes beyond prior work by shedding light on what factors related to practicing safer sex are most salient to clients to discuss with a counselor. We also learned that, when given options, our clients identify a safer sex topic that is salient to them. A majority of clients chose to discuss issues of communication, relationships, and self-care. A substantial minority chose substance abuse as the most salient safer sex issue for them. Safer sex counselors and those developing safer sex programs need to keep in mind that safer sex practices are experienced only within the contextual and social fabric of peoples’ lives. A prevention program that is structured to assess and account for such contextual factors may be more likely to be successful (Robinson et al., 2002). Our next steps are to test the effect of the STAR program on patients’ risky behaviors. Because we have implemented our program among a diverse group of persons that includes those with single and multiple partners, men who have sex with men, women, and heterosexual men, it will be important for us to assess for differential efficacy of the intervention among subgroups.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ross Oglesbee for her administrative and editorial assistance on this manuscript. This research was supported by a Special projects of National Significance (SPNS) grant from Health Resources Services Administration (No. HA01289-02) and by the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410).

Contributor Information

Carol E. Golin, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; UNC Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 725 Airport Road, Campus Box 7590, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7590, USA

Shilpa Patel, UNC Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Katherine Tiller, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

E. Byrd Quinlivan, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Center for Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Catherine A. Grodensky, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Maureen Boland, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

References

- Adamian MS, Golin CE, Shain L, DeVellis B. Motivational interviewing to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Development and pilot evaluation of an intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18(4):229–238. doi: 10.1089/108729104323038900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baele J, Dusseldorp E, Maes S. Condom use self-efficacy: Effect on intended and actual condom use in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:421–431. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Healther N, Wodak A, Dixon J, Holt P. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for HIV prevention among injection drug users. AIDS. 1993;7:247–256. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Kochan N, Dixon J, Heather N, Wodak A. Controlled evaluation of a brief intervention for HIV prevention among injecting drug users not in treatment. AIDS Care. 1994;6:559–570. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thoughts and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher L, Kalichman S, Topping M, Smith S, Emshoff J, et al. A randomized trial of a brief HIV risk reduction counseling intervention for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Maisto SA, Forsyth AD, Wright EM, Johnson BT, Kalichman SC. Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;165:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance Supplemental Report, 10. 2003.

- Diorio C, Resnikow K, McDonnell, Soet J, McCarty F, Yeager K. Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: A pilot study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2003;14:52–62. doi: 10.1177/1055329002250996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory. 2003;13:164–183. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Willcuts DK, Misovich S, Weinstein V. Dynamics of sexual risk behavior in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Golin CE, Earp JA, Tien H, Stewart P, Howie L. A two-arm, randomized, controlled trial of a motivational interviewing-based intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among patients failing or initiating ART. Journal of AIDS. 2006 doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219771.97303.0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golin CE, Patel S, Paulovits K, Quinlivan EB. Development and pilot assessment of a motivational interviewing-based “prevention for positives” program. Proceedings of the CDC prevention conference; Atlanta, GA. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Group SSASDW Southern States Manifesto: HIV/AIDS and STD’s in the South. 2003.

- Hader SL, Smith DK, Moore JS, Holmberg SD. HIV infection in women in the United States: Status at the millennium. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:1186–1192. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes R, Fawal H, Moon TD, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Alabama: Special concerns for black women. Southern Medical Journal. 1997;90:697–701. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199707000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation . HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases in the southern region of the United States: Epidemiological overview. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. Positive prevention: Reducing HIV transmission among people living with HIV/AIDS. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Morgan M, Rompa D. Fatalism, current life satisfaction, and risk for HIV infection among gay and bisexual men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997a;65:542–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Nachimson D, Cherry C, Williams E. AIDS treatment advances and behavioral prevention setbacks: Preliminary assessment of reduced perceived threat of HIV-AIDS. Health Psychology. 1998;17:546–550. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Roffman R, Picciano J, Bolan M. Sexual relationships, sexual behavior, and human immunodeficiency virus infection: Characteristics of HIV seropsoitive gay and bisexual men seeking prevention services. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1997b;28:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, Luke W, Buckles J, Kyomugisha F, Benotsch E, Pinkerton S, Graham J. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee MB, Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Swanson F, Kalichman SC. Marketing the ‘sex check’: Evaluating recruitment strategies for a telephone-based HIV prevention project for gay and bisexual men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(2):116–131. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing skill code (MISC): Coder’s manual. University of New Mexico; Albuquerque, New Mexico: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2002. p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- MMWR HIV transmission among black women—North Carolina. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2005;54:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napravnik D, McKaig RG, Menezes P, Haskins LM, Buerge SS, Abernathy MG, van Der Horst C, Eron JJ. Prevalence and characteristics of HIV-infected individuals who engage in high risk sexual behavior. Proceedings of the XIV international AIDS conference; Barcelona, Spain. 2002. Abstract WePeC6089. [Google Scholar]

- Napravnik S, Edwards D, Stewart P, Stalzer B, Matteson E, Eron JJ., Jr. HIV-1 drug resistance evolution among patients on potent combination antiretroviral therapy with detectable viremia. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2005;40:34–40. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174929.87015.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NC-DHHS, Epidemiology and Special Studies Unit . HIV/STD Prevention and Care Branch Epidemiology Section—Division of Public Health. NC Department of Health and Human Services; Oct, 2006. Updated. http//www.epi.state.nc.us/epi/hiv/surveillance.html. [Google Scholar]

- Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Kalichman SC, Rutledge SE, Berghuis JP. A telephone based brief intervention using motivational enhancement to facilitate HIV risk reduction among MSM: A pilot study. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Reitman D, St. Lawrence J, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, Brasfield TL, Shirley A. Predictors of African American adolescents’ condom use and HIV risk behavior. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8:499–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Carballo-Dieguez A, Wagner G. Intimacy and sexual behavior in serodiscordant male couples. AIDS Care. 1995;7:429–438. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, De AK, McCarty F, Dudley WN, Baranowski T. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through black churches: Results of the eat for life trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(10):1686–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BE, Bockting WO, Rosser BRS, Miner M, Coleman E. The sexual health model: Application of a sexological approach to HIV prevention. Health Education Research. 2002;17:43–57. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: The development of brief motivational interviewing. Journal of Mental Health. 1992;1:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S. Comments on Dunn et al.’s the use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Enthusiasm, quick fixes and premature controlled trials. Addiction. 2001;96:1769–1770. doi: 10.1080/09652140120089517. discussion 1774–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H, Rosario M, Kasen S. Determinants of safer sex patterns among gay/bisexual male adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1995;18:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, Salomon E, Johnson W, Mayer K, Boswell S. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: Life-steps and medication monitoring. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SSASDW . HIV/AIDS and STDs in the South: A call to action. National Center for HIV/STD, and TB Prevention, Div of HIV/AIDS Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2003. Southern States Manifesto. [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Platts S, Groves P. Engaging the reluctant GP in care of the opiate misuser: Pilot study of change-orientated reflective listening (CORL) Family Practice. 2004;21(2):150–154. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss R, Shain L, Baggstrom E, et al. Sexual behaviors in persons living with HIV/AIDS in the non-urban southeast US. Presented at the 129th Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; Atlanta, GA. 2001. Abstract 6013.0. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher A, Golin CE, Earp JA, Porter C, Tien H. Motivational interviewing to improve antiretroviral adherence: The role of quality assessment. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;62:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, Lang DL, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Hook EW, III, Saag M. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: The WiLLOW program. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37:S58–S67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]