Study of attachment in the 1970s and 1980s focused on operationalizing and validating many of the tenets of attachment theory articulated in Bowlby’s landmark trilogy, Attachment and Loss (Bowlby, 1982, 1973, 1980), robustly underscoring the central role of child to parent attachment in the child’s development and mental health. Attachment theory and its implications have long interested clinicians, though determining how best to translate complex theoretical constructs and research methods into the clinical arena has been challenging. Nevertheless, well-defined landmarks in early childhood attachment are clinically useful, and the emergence of interventions drawn from systematic research is promising. The purpose of this paper is to summarize salient issues from attachment theory and research and discuss how these issues inform clinical work with infants and young children.

We recognize that there is a range of clinical settings in which child–parent attachment will be important. Likewise, among practitioners serving young children and their families, there is a broad range of familiarity with and expertise in attachment principles and attachment-based treatment. We assert that all clinical services for young children and their families will be enhanced by providers’ understanding of attachment theory and research. We further assert that in some clinical contexts understanding child–parent attachment is essential.

We begin by reviewing developmental research on attachment to describe how attachments develop, how individual differences in selective attachments manifest, and the characteristics of clinical disorders of attachment. Next, we turn to assessment of attachment in clinical settings. Then, we describe selected specialized clinical contexts in which assessing attachments are uniquely important. Finally, we describe four interventions for young children and their families, all of which are closely derived from attachment theory, supported by rigorous evaluations, and designed to support directly the developing child–parent relationship.

Basics of attachment theory and research

Defining attachment

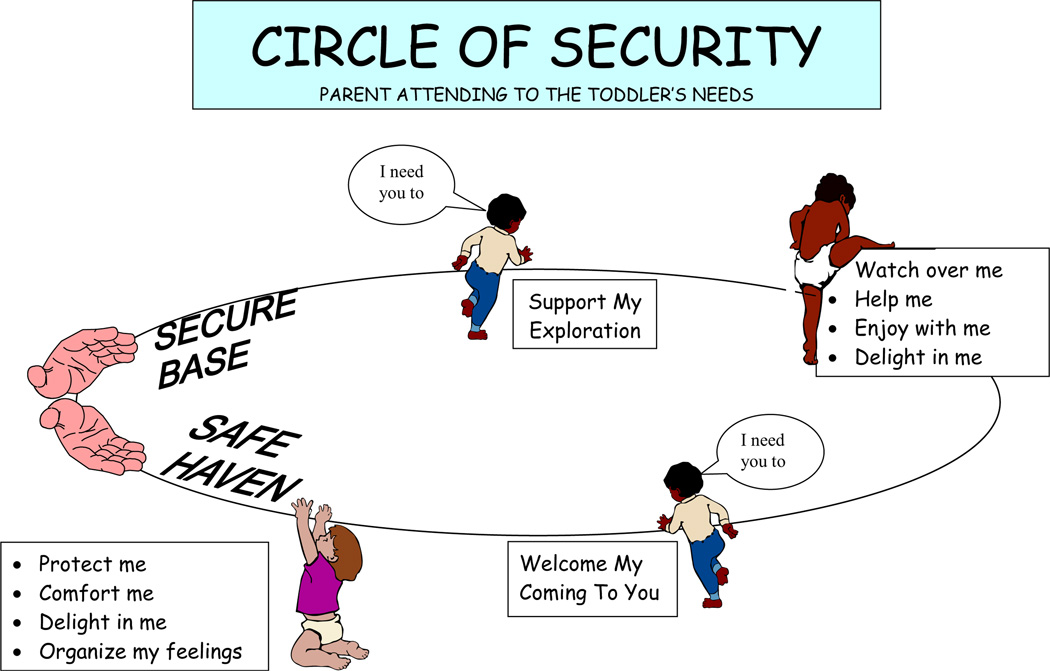

Bowlby defined attachment in young children as ‘a strong disposition to seek proximity to and contact with a specific figure and to do so in certain situations, notably when frightened, tired or ill’ (Bowlby 1969/1982, p. 371). In contemporary use, attachment refers to the infant’s or young child’s emotional connection to an adult caregiver – an attachment figure – as inferred from the child’s tendency to turn selectively to that adult to increase proximity when needing comfort, support, nurturance or protection. Importantly, attachment behaviors are distinguished from affiliative behavior or social engagement with others because they involve seeking proximity when experiencing distress. According to Bowlby, the attachment behavioral system operates in tandem with the exploratory behavioral system, such that, when one is highly activated, the other is deactivated. In other words, if a child feels secure in the presence of an attachment figure, the child’s motivation to venture out and explore intensifies (see Figure 1). If the child becomes frightened or stressed, however, the child’s motivation to explore diminishes, and the motivation to seek proximity intensifies.

Figure 1.

Circle of Security®: parent attending to the toddler’s needs

Development of attachment

Human infants are born without being attached to any particular caregivers. Attachments develop and emerge during the first few years of life in conjunction with predictable major biobehavioral shifts that occur at 2–3 months of age, 7–9 months of age, 18–20 months of age and, less dramatically, at 12 months of age (Table 1). These shifts occur when qualitatively new behaviors and capacities appear for the first time. Between the shifts, it is possible to describe the emergence of infant attachment behaviors. These attachment benchmarks provide a reference for clinicians’ expectations for children of different ages.

Table 1.

Development of attachment in infancy and early childhood

| Biobehavioral shifts and attachment benchmarks during periods between shifts |

Behavioral characteristics |

|---|---|

| First 2 months | Infant has limited ability to discriminate among different caregivers; recognize mothers’ smell and sound but no preference expressed. |

| 2–3 month shift | Emergence of social interaction, with increased eye to eye contact, social smiling and responsive cooing. |

| 2–7 months | Able to discriminate among different caregivers but no strong preferences expressed; comfortable with many familiar and unfamiliar adults and intensely motivated to engage them. |

| 7–9 month shift | Emergence of selective attachment as evidenced by onset of stranger wariness (initial reticence) and separation protest (distress in anticipation of separation from attachment figures). |

| 9–18 months | Hierarchy of attachment figures evident. Infant balances the need to explore and the need to seek proximity; these become even more evident with independent ambulation emerging at approximately 12 months. Secure base behaviors (moving away from the caregiver to explore) and safe haven behaviors (returning to the caregiver for comfort and support) both evident. |

| 18–20 month shift | Emergence of symbolic representation, including pretend play and language. |

| 20–36 months | Goal-corrected partnership in which the child becomes increasingly aware of conflicting goals with others and for the need to negotiate, compromise and delay gratification. |

| 36+ months | Secure base and safe haven behaviors continue but behavioral manifestations become less evident because of the child’s increased verbal skills. Internal representations of attachment more accessible to observers through narrative doll play. |

The developmental milestones in Table 1 are tied to cognitive rather than chronological ages, and they also may be affected to varying degrees by other conditions or circumstances affecting the child. Interestingly, aberrant environmental conditions seem to impair the development of attachment more than physical or neurological child abnormalities do. For example, in children being raised in institutions, the main effect appears to be that attachments are incompletely formed or even absent (Dobrova-Krol et al., in press; Zeanah et al., 2005). In contrast, a meta-analysis drawing on assessments of attachment in over 1,600 infants and their mothers found that intrinsic infants’ challenges, including deafness and Down syndrome, played less of a role in the developing quality of the child’s attachment to the mother than did mothers’ problems, including affective disorders (van IJzendoorn, Goldberg, Kroonenberg, & Frenkel, 1992). Further, although children with autism display aberrant behaviors and are at increased risk for disorganized attachments, it is clear that they form selective attachments (Rutgers et al., 2004). Though it is clear that infants’ developmental abnormalities may lead to some aberrant attachment behaviors, they do not appear to significantly impede the actual formation of attachment, as occurs in rearing environments characterized by extreme social privation.

Once selective attachments have begun to emerge in the latter part of the first year of life, clinicians can focus on the young child’s use of the attachment figure as a secure base from which to explore (illustrated by the top of the circle in Figure 1), and as a safe haven to whom to return in times of distress (illustrated by the bottom of the circle in Figure 1). Individual differences in the young child’s balance between attachment behaviors and exploratory behaviors may vary with different caregivers, as these behaviors are believed to be emergent properties of an infant’s interaction with particular adults. A laboratory paradigm, known as the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP), was developed to examine individual differences in the young child’s balance of attachment and exploration while interacting with an attachment figure and an unknown adult (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

Classifications of attachment in infants and young children

Strange Situation Procedure and classifications of attachment

Designed to assess the child’s balancing of proximity-seeking and exploration, the SSP is the ‘gold standard’ for systematically identifying patterns of infant–parent attachment. The SSP involves a series of interactions between a 12- to 20-month-old infant, a caregiver, and a female ‘stranger.’ Two brief infant–caregiver separations are included as moderate stressors designed to activate the child’s need for caregiver support. Differences in how infants organize their attachment and exploratory behaviors, especially during reunion episodes, can be reliably classified as secure, avoidant, or ambivalent/resistant (Ainsworth et al., 1978 [see Table 2]). A fourth classification, disorganized, is described more fully below. Using a slightly modified SSP, researchers also have identified analogous classifications preschool children (Cassidy & Marvin, 1992 [see Table 2]).

Table 2.

Classifications of attachment in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers according to the Strange Situation Procedure

| Infant and toddler classifications |

Reunion behavior | Estimated prevalence in low risk samples |

|---|---|---|

| Secure | Direct expression of distress elicited by separation, active comfort-seeking, resolution of distress, resumption of exploration. |

65% |

| Avoidant | Minimal response to separation from the caregiver, though quality of exploration may diminish, ignoring or actively avoiding the caregiver on reunion. |

20% |

| Resistant | Intense distress induced by separation, attempts to obtain comfort are limited, awkward or interrupted, little or incomplete resolution of distress on reunion, and resistance of caregiver attempts to soothe. |

10% |

| Disorganized | Anomalous reactions to caregiver that may include mixtures of rapid, incoherent sequences of proximity-seeking, avoidance or resistance, or fearful of the parent, or other behaviors indicating failure to use caregiver as an attachment figure (e.g., trying to get out of the door, preferring the stranger to the caregiver or showing intensely fearful responses in presence of caregiver). |

15% |

| Unclassifiable | Minimal social engagement with caregiver or stranger, little to no evidence of proximity-seeking, avoidance or resistance directed to caregiver, minimal emotional response to separation or reunion. |

Rare |

| Preschool classifications | ||

| Secure | Reconnection with parent through gaze, verbal interaction, greeting; often invitation to joint activity. |

Unknown |

| Avoidant | Avoidance conveyed through child’s orientation away from parent, distance, neutral affect, proximity for ‘business’ purposes (e.g., fixing toys). |

Unknown |

| Dependent | Ambivalence about contact. Helplessness, whiney, petulant or forced over-brightness; also coyness or hesitant, seemingly shy behavior. |

Unknown |

| Disorganized | Similar to infant D pattern if not covered by Insecure/Other behaviors (see below). | Unknown |

| Controlling | Developmentally inappropriate attempts by the child to control the behavior of the parent, through punitive or solicitous, caregiving behavior. |

Unknown |

| Insecure/other | Varies with subtypes (below): | Rare |

| – A/C | combination of avoidant and dependent patterns | |

| – disengaged | child mirrors parent’s lack of responsiveness | |

| – inhibited/fearful | child fears the parent: compulsively compliant behavior | |

| – affectively dysregulated | anxiety manifested as escalating ‘silly,’ ‘goofy,’ ‘hyper’ behavior. |

Disorganized and other atypical patterns of attachment

Among the attachment classifications in infancy, disorganized attachment (Main & Solomon, 1990) is particularly relevant to psychopathology and clinical intervention. Disorganized, disoriented, and frightened behaviors in infants during the SSP may appear as a temporary breakdown in an organized attachment strategy or as a complete lack of strategy for obtaining proximity to increase feelings of security. As some children reach preschool age, disorganization is transformed into controlling/ punitive or solicitous/caregiving behaviors directed towards the parent, though in some high-risk preschool samples, disorganized behaviors remain evident (Smyke, Zeanah, Fox, Nelson, & Guthrie, 2010). In low-risk samples, disorganized attachments have a prevalence of about 15%, whereas in populations of risk, the rates are much higher. For example, in a clinically referred sample of preschoolers the rate was 32% (Greenberg, Speltz, DeKlyen, & Endriga, 1991), but in maltreated preschoolers the rate was 55% (Cicchetti & Barnett, 1991).

Increasing numbers and severity of risk factors within parent or child appear to increase probability of disorganized attachment (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2010; van IJzendoorn et al., 1999). Infants classified as disorganized have been shown to be at increased risk for later externalizing behavior problems, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and dissociation (Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, 2010).

Clinical significance of SSP patterns of attachment

Classifications of attachment in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers have proven enormously valuable for understanding early child–parent relationships. There is consistent evidence from high-risk samples of a connection between insecure attachment during infancy and later internalizing and externalizing problems (DeKlyen & Greenberg, 2008).

Although links between insecure attachment and child psychopathology have been observed less consistently in low-risk families, in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care, a longitudinal multi-site study of over 1,000 US low-risk children, avoidant and disorganized attachment at 15 months predicted lower maternal ratings of social competence and higher teacher ratings of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems from preschool through first grade, and infant attachment security appeared to serve a strong protective function, even when maternal parenting quality declined over time (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2006). For longer-term outcomes, associations with early attachment appear increasingly less likely to be direct and more likely to operate through other relationships and social cognitions (Carlson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2004; Grossman, Grossman, & Waters, 2005).

Attachment patterns, however, should not be confused with clinical diagnoses. Thus, there is no role for the SSP in clinical settings as a diagnostic measure.

To the extent that clinicians can understand what the SSP elicits, however, and how attachment security and insecurity are identified, practice with infants and young children will be enhanced. Thus, as will be described below, the major underlying principles and observational practices of the SSP can be applied to clinical work with infants and young children in ways that should significantly enhance the therapeutic work.

Disorders of attachment

In species-typical rearing conditions, virtually all children develop attachments to their caregivers, and SSP classifications of attachment define qualitatively different patterns. In more extreme rearing conditions, as noted above, such as social neglect or institutional care, attachment may be seriously compromised or even absent. Attachment disorders describe a constellation of aberrant attachment behaviors and other behavioral anomalies that are defined as resulting from social neglect and deprivation. Obviously, no disorder of attachment can exist before a child forms selective attachments, so a developmental age of 9–10 months ought to be required to make the diagnosis.

Two clinical patterns of attachment disorders have been most commonly described: an emotionally withdrawn/inhibited type and an indiscriminately social/disinhibited type (Zeanah & Smyke, 2009). In the emotionally withdrawn/inhibited type, the child exhibits limited or absent initiation or response to social interactions with caregivers and aberrant social behaviors. In particular, when distressed, the child fails to seek or respond consistently to comfort from caregivers and exhibits emotion dysregulation. In the indiscriminately social/disinhibited type, the child exhibits lack of social reticence with unfamiliar adults, failure to check back with caregivers in unfamiliar settings and a willingness to ‘go off’ with strangers. As the child becomes older, he/she exhibits intrusive and overly familiar behavior with strangers, including asking overly personal questions, violating personal space, or initiating physical contact without hesitation.

In DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), the two patterns are considered subtypes of reactive attachment disorder, that is, variations on a unitary construct of disordered attachment. In contrast, in ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992), the emotionally withdrawn/inhibited type is designated reactive attachment disorder, whereas the indiscriminately social/disinhibited type is defined as disinhibited attachment disorder. Recent reviews are consistent in concluding that the evidence favors two distinct disorders because of differences in phenomenology, correlates, and response to intervention (Rutter, Kreppner, & Sonuga-Barke, 2009; Zeanah & Gleason, 2010; Zeanah & Smyke, 2009).

From recent studies, it seems clear that signs of attachment disorders are rare to non-existent in low-risk samples, still rare in higher-risk samples, but readily identifiable in maltreated and institutionalized samples (Zeanah & Smyke, 2009). Recent research has demonstrated that these disorders often remit when caregiving conditions improve, though with variability for each type: the emotionally withdrawn/inhibited type is more responsive to intervention whereas the indiscriminately social/ disinhibited type is more resistant and may persist in some children for years.

The relationship between attachment disorders and classifications of attachment is not straightforward (Rutter, Kreppner, & Sonuga-Barke, 2009). There is some tendency for more atypical classifications of attachment to be present when children have attachment disorders (Boris et al., 2004; Gleason et al., 2011; O’Connor et al., 2003; Zeanah et al., 2005), but some children with high levels of indiscriminate behavior also demonstrate secure attachment (Gleason et al., 2011; O’Connor et al., 2003; Zeanah et al., 2005).

Assessing attachment in clinical settings

Assessment of attachment involves a paradigmatic shift in the clinical frame. Following the long tradition of medicine, psychiatric disorders are conceptualized as existing within an individual, even if the disorder has significant interpersonal manifestations (e.g., conduct disorder). The quality of the caregiver–child attachment, on the other hand, requires shifting from considering clinical problems as existing within an individual child to conceiving of clinical problems (and strengths) existing between caregiver and child. One major implication of this shift is recognizing that the same child may be differentially attached to different caregivers. This shift in the clinical frame from the individual to the dyad has implications for both assessment and treatment.

Two clinical approaches, derived from research, are fundamental to adequate assessment of attachment in young children: (a) a structured interaction between caregiver and child designed to examine the way that the young child uses the caregiver to balance between the need to explore and the need to seek physical closeness (see Figure 1), and (b) a narrative interview with the caregiver. As discussed below, these approaches may be implemented through formal and validated measures or less systematically with attention to naturalistically observed behavior and narrative qualities in describing the child. Such approaches are likely to be significantly more useful when they are videotaped so that clinicians and clinicians and parents can review them later. Though not available in all clinical settings, videotaping is increasingly central to work with young children and their families (Miron, Lewis, & Zeanah, 2009).

Video review with parents is valuable because it augments and facilitates reflective functioning, that is, parents’ ability to notice and reflect upon their own and their infants’ behavior. Increasingly, reflective functioning is recognized as a component of the parent’s ability to function as a secure base and safe haven for the child (Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005). As a result, reviewing videotaped interactions with parents also is a central component of most manualized attachment-based interventions, reviewed in detail later.

Assessing caregiver–child interaction

There are various interactional assessments that may be used to elicit attachment-relevant behaviors (Miron, Lewis, & Zeanah, 2009), but procedures that involve active elicitation of the child’s attachment behaviors are most useful. Reunion following a brief separation, whether as part of the SSP or some other method, is often considered the most reliable elicitor of attachment behaviors. Separation activates the child’s need for comfort, and during the reunion, the caregiver must read and respond to the child at a moment of intense emotional arousal. The clinician’s task is carefully to analyze how the dyad resolves distress following separation or positively reconnects even in the absence of distress. Note that this does not mean determining the SSP classification but instead noting how attachment behaviors are organized within a particular relationship.

Especially in the context of a reunion, but also during naturalistic observations, there are several aspects of child–parent interaction that merit close consideration. First, careful attention to presence or absence of child behaviors that reflect proximity-seeking, avoidance, resistance or disorganization in response to distress may be useful in highlighting strengths and weaknesses in the parent–child relationship. Especially important is observing the balance between the child’s exploring and proximity-seeking and the child’s use of the caregiver to regulate distress and other negative emotions (see Figure 1). Behaviors that are clinically salient include the child’s showing affection to the caregiver, seeking closeness – especially when needing comfort, relying on the caregiver for help, and cooperating with the caregiver (Boris, Aoki, & Zeanah, 1999).

Familiarity with disorganized and other atypical attachment behaviors is of particular clinical value. Disorganized attachment behaviors have been described in some detail (Main & Solomon, 1990), but training from videotapes is a useful adjunct to written descriptions. In preschoolers, controlling behaviors – whether evident as solicitous caregiving or as being bossy and punitive – should be noted. The ‘insecure/other’ behaviors described in Table 3 are also important indicators of disturbed attachment relationships.

Table 3.

Atypical parenting behaviors associated with disorganized attachment (adapted from Benoit, 2000, and based on the Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification Scale) (Lyons-Ruth & Jacovitz, 2008)

| Atypical parenting behaviors | Examples |

|---|---|

| Withdrawal | Creating physical distance – directing the child away with toys; not greeting on reunion |

| Fearful behaviors | Frightened/hesitant/uncertain – haunted or high-pitched voice, sudden mood change, dissociation/’going through the motions’ |

| Role confusion | Pleading with the child, threatening to cry, hushed tones, speaking as if the child were an adult partner |

| Affective communication errors | Contradictory signals – inviting approach, then directing child away; using a positive voice, but teasing or putting the child down; laughing at child’s distress and/or expressing distress in response to the child’s positive affect |

| Intrusiveness/Negativity | Mocking, teasing, derogating; withholding a toy; pushing the child away; hushing the child |

Co-occurrence of clinical problems of a variety of types with disorganized attachment behaviors may increase urgency about intervening to change the child–parent relationship. Here, efforts to increase parental behaviors associated with child security, such as sensitive caregiving (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997) and reflective functioning (Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005), may be important clinical efforts. Problematic parental behaviors such as frightening or frightened behaviors, which have been linked both to trauma and to disorganized attachment (Schuengel et al., 1999), are important to identify. These behaviors could in turn be targeted through specific attachment-based interventions (described in more detail below) and/or through related modalities already practiced successfully by the clinician.

Given considerable evidence that attachment classifications can differ with different caregivers (Fearon et al., 2010), relationship-specific information about how attachment behaviors are organized may impact how interventions are designed. Throughout observation, clinicians should expect the child’s attachment behaviors to be organized towards the attachment figure (i.e., parent or care-giver) and to contrast sharply with the child’s behavior with an unfamiliar adult (usually the clinician). Any direction of the child’s attachment behaviors directly towards the unfamiliar adult indicates a significant disturbance. Similarly, parent–child attachment relationships are asymmetrical, meaning that it is the parent’s job to provide comfort, support, nurturance and protection to the child but not the other way around. Indications of abdication of the parental role are clinically significant, as are indications that the child is the one structuring the interaction with the parent and/or treating the parent in a caregiving manner.

Observations should be supplemented by detailed interview questions about typical behaviors that are clinically salient to attachment. In the latter part of the first year, these would involve stranger wariness and separation protest, and then in the second year would include behaviors describing the child’s balance between, and comfort with, exploratory behavior and proximity-seeking. Use of the caregiver to regulate distress and other negative emotions, seeking comfort and closeness, particularly when distressed, showing affection to the caregiver, relying on the caregiver for help, and cooperating with the caregiver are all important (Boris et al., 1999).

On the caregiver side, there are also behaviors especially important to note. Because of the link with disorganized attachment, frightening or frightened behavior by the caregiver are especially notable (Hesse, 2008). In addition, other behaviors reflecting emotionally disrupted communications have been described by Lyons-Ruth and colleagues (Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Riley, & Atlas-Corbett, 2009) and are linked to disorganized attachment ([Table 3] see also Benoit, 2000). These behaviors include overt and covert hostility, withdrawal, and mismatched affect (e.g., the parent laughs at the child’s upset, or acts upset when the child expresses joy).

Of course, careful observation of the interaction between caregiver and child in isolation reveals little to the clinician about what underlies the caregiver’s difficulty in meeting his or her child’s needs. Bowlby (1969/1982) posited, and subsequent research has confirmed (van IJzendoorn, 1995), that each care-giver’s interactive behavior with the child is influenced largely by their own ‘internal working models’ of attachment, forged in part by their own early family experiences.

Assessing the caregiver’s narrative

The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) developed by Main and colleagues heralded ‘a move to the level of representation’ in attachment research (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Main and colleagues argued that the AAI assessed internal representations of attachment, indicating different ‘states of mind’ with respect to attachment. This includes patterns of emotion regulation, attachment information processing and the degree to which attachment is valued (Steele & Steele, 2008).

The major advance provided by the AAI was to analyze patterns of narrative discourse about early childhood relationship experiences. Instead of merely accepting reports of childhood relationship experiences at face value, this approach evaluates the reports in terms of well-anchored qualitative features of the narrative. Some adults, classified as ‘autonomous,’ relate organized, emotionally integrated narratives about their experiences and in which they clearly value attachment relationships. Those classified as ‘dismissing’ minimize the importance of attachment experiences often while idealizing their childhood experiences, yet at the same time failing to provide credible memories to support their descriptions. Narratives in which the adult provides incoherent, affect-laden stories without an overall, integrated perspective are classified as ‘preoccupied.’ Finally, narratives in which the adult has lapses in coherence when discussing traumatic experiences or losses are classified as ‘unresolved.’ A rarer group, lacking sufficient indicators of the preceding, is ‘cannot classify’ (see Hesse, 2008, for a comprehensive review). A meta-analysis of more than 800 dyads found significant concordance (70%), as predicted, between classification of infant–parent attachment patterns from the SSP and classification of parental state of mind regarding attachment from the AAI (van IJzendoorn, 1995).

As with the SSP, actual attachment classifications from the AAI are less important in clinical settings than the behaviors – in this case, narrative qualities – underlying them, which are often quite usefully noted. Steele and Steele (2008) detailed a number of ways in which the AAI may be useful in clinical settings. Among others, they noted the AAI may be useful in helping to set the agenda for psychotherapy, uncovering traumas or losses, delineating defensive processes, assessing reflective functioning, and identifying positive relationship models from which to build. Specific uses of the interview will vary with the setting and the specific clinical issues being addressed.

Following the AAI, other narrative interviews were developed. For example, rather than focus on the caregiver’s past experiences with caregiving relationships, interviews like the Working Model of the Child Interview (WMCI; Zeanah et al., 1994) and the Parent Development Interview (Slade et al., 1999) focus on the caregiver’s perceptions of the child and their relationship with their child. The WMCI also has been shown to be concordant with SSP classifications (Zeanah et al., 1994), even when administered before the child is born (Benoit et al., 1997).

These and other narrative interviews have been used in both evaluation and treatment planning. Narrative interviews take approximately one hour to conduct and, like the interactive piece of the assessment, are best video recorded for later review. In some clinical settings, interviews about caregivers’ childhood experiences may be desirable and illuminating. In others, such as settings in which the child is the clinical focus, parents may find questioning about their own childhood objectionable, and interviews about the child may be better tolerated. The Circle of Security Interview (Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, 2009) is a hybrid that includes probes about both the parent’s childhood relationships and relationships with the child. Narrative features of interviews about the caregiver’s relationship with the child that are clinically salient are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Clinically relevant features of narrative attachment interviews

| Narrative feature | Examples of areas of clinical concern |

|---|---|

| Attributions about the child |

|

| The tone of the interview |

|

| The capacity to reflect on the child’s experience (i.e., reflective functioning, empathy and insight) |

|

| Memories about the child |

|

| Psychological defenses/ trauma |

|

Importantly, it is not necessary to obtain training to reliability in these measures to find them clinically valuable, especially since an overall classification is not necessarily in and of itself illuminating. Furthermore, in clinical use, deviation from strict research administration protocols is often indicated in order to pursue more details about important issues. Nevertheless, detailed understanding of narrative features and how they relate to emotion regulation in parent and child means that training in administration and interpretation of a particular interview will enhance its usefulness for the clinician. Finally, for less experienced clinicians the structure afforded by these interviews may be valuable if it does not become overly rigid.

There is, however, a significant cost in time, both in conducting interactive assessments and narrative interviews, and in being trained to interpret the data provided by such measures. Still, these measures may be clinically valuable whether used alone or as part of attachment-based interventions (Steele & Steele, 2008; Zeanah & Benoit, 1995).

Selected clinical contexts

Although we suggest that attachment ought to be a prominent component of assessment of young children in any clinical setting, there are certain situations in which attachment assessment should have a central role. We next turn to a discussion of applications of attachment theory and research in four specific clinical contexts.

Maltreatment and foster care

Attachment disturbances are inherent in foster care for several reasons. First, young children are disproportionately likely to be classified as disorganized in relation to their maltreating parents, with rates of disorganization found to be as high as 90% (Cicchetti et al., 2006). Second, as noted, maltreatment, and specifically neglect, are necessary but not sufficient as etiologic conditions for attachment disorders (Zeanah & Smyke, 2009). Third, maltreated children who are removed from their primary caregivers and placed with foster parents they often have never seen before must form attachments to entirely new care-givers. Finally, these children must attempt to resolve and/or repair attachments to their biological parents even as they develop new attachments to foster parents.

An initial question for clinicians evaluating young children in foster care is whether they are attached to anyone. For example, one study found that about a third of 1- to 4-year-old children removed from their parents and placed in foster care had limited or no attachments three months after their removal (Zeanah et al., 2004). Dozier and colleagues (Stovall-McClough & Dozier, 2004) had foster parents complete structured daily diaries to describe the nascent attachment behaviors of the young children in their care. They noted that attachments began to organize as secure, avoidant or resistant patterns within days to weeks of placement. Thus, attention to development and quality of attachment to foster parents should be monitored from the outset. Important questions for the clinician include: Does the child consistently turn to preferred attachment figures for comfort, support, nurturance and protection? Does the child directly express negative emotions? Is the child convincingly comforted when seeking it from preferred attachment figures?

Barriers to the formation of attachments and particularly secure attachments may come from parent or child or from the unique fit between the two. Stovall-McClough and Dozier (2004) reported that children placed prior to 10 months of age readily developed secure attachments to their foster parents, but those placed after 10 months were more likely to exhibit insecure behavior when distressed. Importantly, they noted that when children avoided their foster parents, the foster parents responded with withdrawal, and when children exhibited resistance in the form of difficulty settling once distressed, foster parents responded with impatience and irritability. These cycles can be identified soon after placement and should be the target of clinical intervention.

Clearly, clinical intervention should begin with helping foster parents understand children’s attachment and exploratory needs, but also with teaching foster parents that traumatized children often mislead caregivers about what they need. Caregivers, thus, must override their own problematic reactions to challenging behaviors (Dozier et al., 2005). In fact, foster parents’ own state of mind with respect to attachment has been identified as the strongest predictor of whether foster children will become securely attached to them (Dozier et al., 2001).

Another critical component is foster parents’ commitment to the children in their care. Young children have an urgent need for regular and substantial contact with their attachment figures, and it is rarely possible for biological parents to serve this function even with frequent visitation. Dozier (2007) found that greater commitment by foster parents to the young child in their care was associated with fewer placement disruptions. Parental commitment also is salient in work with post-institutionalized, adopted children, to which we turn next.

Post-institutionalized and inter-country adopted children

Attachment disturbances are among the most prominent problems noted in post-institutionalized children and among those who are adopted into another country (Zeanah, 2000). In addition to reduced security and increased prevalence of atypical classifications (e.g., insecure/other) in these children, high levels of indiscriminant behavior are quite common. Even after children have established attachments in their adoptive families, some continue to exhibit high levels of indiscriminate behavior (Rutter et al., 2007). In studies to date, children who are placed in families following early institutional rearing develop more secure and less atypical patterns of attachment following enhanced caregiving. For example, the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP) included careful assessment of attachment of young children being raised in institutions (Zeanah et al., 2005). Following this assessment, children were randomly assigned to foster care or to ‘care as usual.’ In this study, the intervention was an attachment-based model of child-centered foster care, and a team of Romanian social workers trained and supported foster parents in managing the complex challenges of caring for post-institutionalized infants and toddlers (Smyke et al., 2009). Paralleling Dozier’s emphasis on commitment (Lindheim & Dozier, 2007), these foster parents were urged by their Romanian social workers to commit fully to the children in their care and to love them as their own. Children were placed between the ages of 6 and 30 months, and through 54 months of age, only two placements disrupted (Smyke et al., 2009). By 42 months of age, secure attachments were significantly increased and atypical (disorganized and insecure other) attachments were significantly decreased in children in foster care compared to children who experienced more prolonged care in institutions (Smyke et al., 2010). Furthermore, recent data from this group indicate that, for girls (but not boys), security of attachment fully mediated the effect of the intervention on internalizing disorders (McLaughlin et al., under review). Timing of removal from institutional rearing also matters, as a recent meta-analysis indicated that for children in adoptive homes for an average of 26 months, those who were adopted before 12 months of age were significantly more likely to be securely attached than those adopted after (Van den Dries, Juffer, van IJzendoorn, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2009).

What is less clear from adoption studies and the BEIP is which parental behaviors and characteristics most strongly promote secure attachments in children with histories of institutional rearing, although this is a current area of investigation. Until more data are available, clinicians ought to be guided by the findings derived from studies of maltreated children. For example, Dozier et al. (2001) showed that infants who had experienced serious neglect could form secure attachments to their new care-givers, but this was far more likely if their mothers had organized (i.e., secure) responses during the AAI. Similarly, a study of 4- to 7-year-old children who had experienced multiple foster placements and who had had disorganized attachments to their bio parent became securely attached in their new placements if they were placed with an adoptive parent who was classified as secure according to the AAI (Steele et al., 2008).

These findings from maltreated children (Dozier et al., 2002; Steele et al., 2008) and what evidence there is from studies of post-institutionalized children (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., in press) converge on several key clinical issues. Parents adopting post-institutionalized children must be encouraged to learn what children need regardless of the off-putting signals the children may transmit. Clinicians should also identify impediments to parents’ making a full commitment to the children. Also, parents’ own attachment histories (and interpretations of their histories) are likely to be important for informing their parenting behaviors, suggesting that clinicians ought to help them increase reflective capacity and understanding of both their children’s behaviors and their own responses to them. Increasing parents’ reflective capacities is a central feature of intervention efforts, including those with children experiencing parental divorce.

Divorce and child custody

There is widespread consensus about the relevance of attachment theory, research, and assessments to child custody decision-making required when parents divorce, including legal custody, physical custody, daily and overnight visitation, and relocation (see Byrne, O’Connor, Marvin, & Whelan, 2005, for a comprehensive review).

Although it is hard to determine the proportion of these decisions that require a court hearing and/or other forms of dispute resolution (e.g., mediation), it is likely that those that do are more complex and contentious, and can include accusations by one parent concerning the other’s suitability to parent their child. Exactly how best to apply attachment theory and research to custody decisions is not well determined, however.

Recent thoughtful and comprehensive reviews have recommended that principles of attachment theory and well-validated measures of attachment security can help to inform custody evaluations (Byrne et al., 2005; Calloway & Erard, 2009). At the same time, standard attachment measures such as the SSP have not yet been widely used nor evaluated in the context of divorce and custody litigation. The resources required to use standard attachment assessments may be prohibitive in the context of divorce and custody litigation. Moreover, even if affordable and well implemented, it is not clear how assessments of attachment security should be brought to bear on custody decisions (Garber, 2009). That is, best interest of the child determinations should be informed by more factors than attachment alone, unless serious disturbances of attachment with either parent are evident. Ideally, young children can enjoy the benefits of regular contact and sustained relationships with both parents and other family members through the inevitable stressors accompanying divorce.

Sometimes, because of conflicts or logistics, this will not be possible, however. Specific issues of issues of separation and loss are especially important in the context of divorce. When parents do not co-reside and/or rarely share time together as a family, young children who have been attached to both parents may have chronic feelings of loss and longing to be with both attachment figures at once. The question is how best to manage these situations.

Once attachment to a parent develops, usually at a cognitive age of 7 to 9 months, any visitation with the non-custodial parent most likely will involve separation from the primary attachment figure. Sustaining attachments to different adults living apart may not be developmentally possible for young children, and separations such as overnight visitations for children younger than 2 or 3 years may not only harm the primary attachment relationship, they can also make establishing a healthy attachment to the non-custodial parent more difficult (see Solomon & George, 1999). For this reason, in children younger than 2 or 3 years old, extended visits with the noncustodial parent may best be accomplished if the custodial parent is present, assuming that parents can be together without conflict. For preschool children, who have a greater capacity to sustain attachments over time and distance, sustaining attachments to both parents may be possible.

Child comfort may be increased if parents can maintain the child’s routines for sleeping/waking, feeding, and activities in both settings. Child comfort will also be increased by both parents allowing the child to use the same transitional object (e.g., favorite stuffed animal) when with both of them, and by their following similar rules for the use of the child’s bottle and/or pacifier. Similarly, although often a source of parental conflict, both parents’ use of the same or similar parenting strategies with respect to emotional soothing and limit-setting will provide a more consistent and coherent child-rearing environment, as a whole. For older toddlers and preschool-aged children, consistency in parents’ narratives about why they are apart should also be helpful.

High levels of parental conflict are likely to increase the probability of attachment disturbances in young children, perhaps through reduced sensitivity in parents who are preoccupied by their own concerns. When high levels of conflict, including violence, are evident, the threats to attachment relationships are even greater.

Families with intimate partner violence

Partner violence is considered both a reflection of and a risk for disorganized attachment (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, 2008). As Kobak and Madsen (2008) note, partner violence is likely to undermine the child’s confidence in the parent’s availability and is a context in which the child is likely to be frightened of and for the parent. Therefore, it is not surprising that within a group of impoverished young mothers, partner violence was significantly associated with disorganized infant attachment (Zeanah et al., 1999).

Lieberman and colleagues have noted that the effects of partner violence on young children and their relationships may be lasting (Lieberman, Ghosh Ippen, & Van Horn, 2006). For clinicians helping families recover from exposure to partner violence, establishing a safe and secure living situation is the most important initial consideration. The clinician should work to make the physical environment as safe as possible: re-establishing routines and rituals for the child, restoring interpersonal connections, and highlighting the fact that protection of the child’s needs are part of this effort. Children who are constantly afraid about the wellbeing of a traumatized caregiver can become overly concerned about the caregiver’s emotional wellbeing; this means that emphasizing protection includes restoring or establishing caregiver limit-setting and developing a treatment plan to address caregiver– child role reversal when it is apparent. Partner violence is a potent risk factor for disorganized attachment and/or role-reversed relationship disturbances (Macfie et al., 2008). Attachment-based interventions are often warranted when exposure to partner violence is prolonged (Lieberman et al., 2006).

Attachment-based interventions

A number of early childhood interventions are compatible with or derived from Bowlby’s work (see Berlin, Zeanah, & Lieberman, 2008, for a comprehensive review). We consider four examples of interventions that derived in whole or in part from attachment theory and research. All of these therapies have an evidence base supporting them, as well as specific training protocols or processes through which clinicians may train to fidelity in one or more of these approaches. Even if not training to research reliability, clinicians will likely enhance their practices by becoming familiar with the detailed nuances of implementing these interventions. It is important to note that these interventions are not employed only in the case of attachment disorders, but rather to support the development of child–parent attachment in high-risk conditions and/or to address concerning child–parent interactions and relationship disturbances.

Child–Parent Psychotherapy (CPP)

The oldest dyadic psychotherapy that shared the relational focus of attachment theory was Fraiberg’s Infant Parent Psychotherapy (Fraiberg, 1980), since refined and extended to serve infants and preschool children by Lieberman and colleagues (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2005). Now called Child–Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), this manualized dyadic intervention has been used primarily with impoverished and traumatized families with children younger than 5. CPP sessions include both parent and child together and take place either in the home or in an office playroom. Sessions are unstructured, with the themes largely determined by the parent and by the unfolding interactions between the parent and child. CPP emphasizes enhancing emotional communication between parent and child, sometimes by exploring links between the parents’ early childhood experiences and their current feelings, perceptions, and behaviors towards their children, as well as a focus on the parent’s current stressful life circumstances and culturally derived values. This emphasis on emotional communication, and defensive processes that threaten to distort it, highlights the link between attachment theory and CPP.

Five randomized clinical trials support the efficacy of CPP. These include infants of stressed, immigrant families (Lieberman, Weston, & Pawl, 1991), infants and preschoolers from maltreating families (Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 2006; Toth, Maughan, Manly, Spagnola, & Cicchetti, 2002), toddlers of depressed mothers (Cicchetti, Toth, & Rogosch, 1999; Toth, Rogosch, Manly, & Cicchetti, 2006), and preschoolers exposed to partner violence (Lieberman et al., 2006). In each, a central component of the therapy is establishing open expression of the child’s experience of distress and a need for the parent to respond effectively, much as is seen in secure attachment relationships.

Video-based Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting (VIPP)

Video-based Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting (VIPP) is a brief, home-based attachment intervention delivered in four home visits to parents of infants less than 1 year old, typically in lower-risk families (Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007). VIPP was drawn explicitly from attachment research and attempts to promote maternal sensitivity through interveners’ presentation of written materials and review of in-home, videotaped infant–parent interactions. An expanded version, VIPP-R, provides an additional three-hour home visit that focuses on the parent’s childhood attachment experiences.

Findings are generally supportive of positive program effects on sensitive and nurturing parenting behaviors, attachment disorganization, and externalizing behavior problems during preschool (Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2005; Klein Velderman, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Juffer, & van IJzendoorn, 2006a; Klein Velderman et al., 2006b). VIPP-SD, a version of VIPP emphasizing sensitive disciplinary practices for toddlers with early signs of externalizing problems, has shown positive effects on mothers’ disciplinary attitudes and behaviors compared to control mothers (Mesman et al, 2007; van Zeijl et al., 2006).

The Circle of Security® (COS)

The Circle of Security was developed as an intervention to enhance attachment relationships between infants and young children and their caregivers, primarily through work with parents (Marvin et al., 2002). Originally created as a time-limited group psychotherapy using video feedback, the intervention is easily adapted for individual therapy. More recently, parenting DVDs based on the model have been created; these combine education about attachment with an opportunity for caregivers to reflect on their child’s needs and the challenges each faces in meeting those needs (Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2009). For the video-therapy approach, an observational procedure including the standard SSP and the Circle of Security Interview are completed at baseline for treatment planning (Powell et al., 2009). Toward the end of treatment, a second SSP is conducted for additional review. In this treatment, the SSP is used to not to classify attachment patterns, but rather to illustrate the parent’s emotional presence and the child’s exploratory and comfort-seeking behavior (see Figure 1).

The intervention emphasizes the sophisticated capabilities of young children and draws caregivers’ attention to the meaning of subtle behaviors, using video review liberally to highlight positive moments of parent–child interaction in order to engage the caregiver. This approach builds upon the work of McDonough (McDonough, 2000; Rusconi-Serpa et al., 2009) and Shaver and colleagues (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007), both of whom demonstrated that images of positive interactions effectively engage difficult-to-reach parents and build unity in groups.

Another key element of the COS approach is education of caregivers about attachment and its development. Once again, review of video material is central. The Circle (Figure 1) is provided as a visual guide for parents to learn about young children’s attachment needs and necessary caregiver behaviors, including supportive presence (‘Hands’), support for exploration (‘top of the Circle’), and support for closeness (‘bottom of the Circle’). The intervention aims to help parents better understand their child’s attachment needs and to recognize when their own reactions impede an appropriate response.

There are preliminary data on the efficacy of the Circle of Security intervention. A pre–post study of impoverished parents showed significant changes in the proportion of securely attached toddlers. A study of a perinatal Circle of Security intervention, provided to pregnant, nonviolent offenders with a history of substance abuse, demonstrated rates of infant attachment security (70%) and disorganization (20%) comparable to those in low-risk samples (Cassidy et al., 2010). Although no randomized, controlled trial has been conducted, COS is tightly linked to attachment theory and research and, in its use of video feedback and promotion of caregiver reflection, leverages emerging best practices.

Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC)

Dozier and her colleagues developed a 10-session intervention aimed at reducing barriers to the development of secure attachment relationships between foster parents and the young children in their care (Dozier et al., 2005). They note four major areas of challenge facing caregivers who foster young children: (a) young children in foster care may reject care that is offered to them, (b) caregivers’ own histories may interfere with their providing nurturing care, (c) young children in foster care may need special help with self-regulation, and (d) young maltreated children may be especially sensitive to frightening behavior in caregivers.

These premises were used to develop the ABC program’s four treatment modules: (a) parental nurturance, (b) following the child’s lead, (c) ‘overriding’ one’s own history and/or non-nurturing impulses, particularly as regards off-putting behavior and negative emotional reactions in children, and (d) avoiding frightening behavior with the child. Carefully selected videotaped examples drawn from interactions between the foster parent and foster child are used to discuss and develop these themes. In addition, live interactions between parent and child are included as part of the therapeutic focus.

A randomized controlled trial of the ABC intervention with foster parents compared it to a psychoeducational intervention of comparable intensity and frequency in 60 children between 3 months and 3 years of age and their foster parents (Dozier et al., 2006b). Initial results demonstrated normalization in diurnal cortisol levels in 93 foster children between the ages of 3 months and 3 years (Dozier et al., 2006a; Dozier, Peloso, Lewis, Laurenceau, & Levine, 2008). A subset of 46 children whose parents had received the ABC intervention showed significantly less avoidance than children of parents in the psychoeducational intervention (Dozier et al., 2009).

The ABC program has been adapted and is being evaluated with birth parents whose young children have been maltreated but not removed from them. The approach is also now being used with inter-country adopted children. That nearly identical interventions are applied to foster parents, maltreating parents, and adoptive parents speaks to the fundamental attachment needs in young children.

Contraindicated interventions claiming attachment derivation

Despite the recent development of well-validated interventions to improve child–parent attachment, there are other clinical interventions which have been developed with the goal of treating children who have a history of disruptions in early attachment who also have developed oppositional or aggressive behavior. Although early traumatic experiences coupled with disruptions in attachment can be associated with aggressive behavior in affected children (Heller et al., 2006), proponents of the various treatments designed to promote ‘reattachment,’ through coercive holding and rebirthing, for example, have effectively rewritten the criteria for attachment disorders and created a series of loosely related interventions which are coercive and dangerous (see Chaffin et al., 2006, for a review and recommendations). Treatments which force children to submit to being held or to sustain eye contact, promote regression to achieve ‘reattachment,’ or encourage children to ‘vent anger’ while being restrained are not only contraindicated, but such treatments have led to injury and even death (Mercer, Sarner, & Rosa, 2003).

Conclusions

Developmental research has established parent– child attachment as a central aspect of social and emotional development. Established landmarks detailing the emergence of attachment in children during the first few years of life describe an expected developmental trajectory against which an individual infant may be compared. In addition, there are clearly defined phenotypes associated with extreme disturbances, including attachment disorders. In most clinical settings, young children’s attachment should be assessed routinely, either formally or informally. Moreover, there are many clinical settings in which a thorough knowledge about attachment and its manifestations ought to be a central focus, such as children who are maltreated (especially those in foster care), adopted children (especially post-institutionalized), children of divorce, and children exposed to parental violence. Information about the development of attachment in early childhood is widely available, though it is our impression that many training programs which lack infant mental health expertise do not adequately cover this material or its applications. For this reason we have emphasized throughout that thorough understanding of attachment and its developmental course is essential in all clinical settings serving young children and their families. More specialized attachment expertise will likely enhance clinical work with young children and their families.

The relational paradigm that attachment research has informed now dominates the interdisciplinary field of infant mental health. In working with young children and caregivers, clinicians have been provided methods for assessing both external, observable interactive behaviors between caregiver and child, and internal, subjective experiences of caregivers about their child. Understanding the internal and external components of the relationship allows clinicians to shift the clinical frame from an individual child to a child developing in the context of caregiving relationships. Though available, these methods require some training to master and may require additional time and resources to implement meaningfully. Our view is that these additional investments are amply rewarded by the richness of the data they provide.

Finally, there is a growing evidence base about effective attachment derived/compatible early childhood interventions that have been shown to be effective. They share an emphasis on enhancing caregivers’ appreciation of the complexity of the emotional development of young children, the power caregivers have to affect their children, and the kinds of factors within and around the caregiver that may interfere with providing what young children need. For clinicians who work regularly with young children and their families, these approaches also demand much but offer more to those willing to invest in their mastery and implementation.

Acknowledgements

Charles H. Zeanah’s work on this paper was supported in part by NIMH R01 MH091363-01 (Charles Nelson, PI); Lisa Berlin’s work on this paper was supported by NIMH K01MH70378 and by NIDA P30DA023026/the Duke University Transdisciplinary Prevention Research Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Ainsworth MD, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual. 4th edn, text rev. Arlington, VA: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Steele H, Zeanah CH, Muhamedrahimov RJ, Vorria P, Dobrova-Krol NA, Steele M, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Gunnar MR. Attachment and emotional development in institutional care: Characteristics and catch-up. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groza VK, Groark CJ, editors. Children without permanent parental care: Research, practice, and policy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development; (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D. Atypical caregiver behaviours and disorganized infant attachment. Newsletter of the Infant Mental Health Promotion Project (IMP) 2000;29:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Parker K, Zeanah CH. Mothers’ representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infants’ attachment classifications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Zeanah CH, Lieberman AF. Prevention and intervention programs for supporting early attachment security. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 745–761. [Google Scholar]

- Boris NW, Aoki Y, Zeanah CH. The development of infant–parent attachment: Considerations for assessment. Infants and Young Children. 1999;11:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Boris NW, Hinshaw-Fuselier SS, Smyke AT, Scheeringa M, Heller SS, Zeanah CH. Comparing criteria for attachment disorders: Establishing reliability and validity in high-risk samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:568–577. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Separation. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Loss. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. 2nd edn. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JG, O’Connor TG, Marvin RS, Whelan WF. Practitioner review: The contribution of attachment theory to child custody assessments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:115–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calloway G, Erard RE. Introduction to the special issue on attachment and child custody. Journal of Child Custody. 2009;6:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Sroufe LA, Egeland BE. The construction of experience: A longitudinal of representation and behavior. Child Development. 2004;75:66–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Ziv Y, Stupica B, Sherman LJ, Butler H, Karfgin A, Cooper G, Hoffman KT, Powell B. Enhancing attachment security in the infants of women in a jail-diversion program. Attachment and Human Development. 2010;12:333–353. doi: 10.1080/14616730903416955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Marvin RS The MacArthur Working Group on Attachment. Attachment organization in preschool children: Coding guidelines. 4th edn. University of Virginia; 1992. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Hanson R, Saunders BE, Nichols T, Barnett D, Zeanah C, et al. Report of the APSAC task force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:76–89. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Barnett D. Attachment organization in maltreated preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. Fostering secure attachment in infants in maltreating families through preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:623–649. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Rogosch FA. The efficacy of toddler–parent psychotherapy to increase attachment security in offspring of depressed mothers. Attachment and Human Development. 1999;1:34–66. doi: 10.1080/14616739900134021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G, Hoffman KT, Powell B. Circle of Security: COS-P facilitator DVD manual 5.0. Spokane, WA: Marycliff Institute; 2009. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of metaanalyses. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:87–108. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKlyen M, Greenberg MT. Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 637–665. [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff M, van IJzendoorn MJ. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68:571–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol NA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on preschoolers’ attachment and indiscriminate friendliness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02243.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Higley E, Albus KE, Nutter A. Intervening with foster infants’ caregivers: Targeting three critical needs. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lindheim O. This is my child: Differences among foster parents in commitment to their young children. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:338–345. doi: 10.1177/1077559506291263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lindheim O, Ackerman J. Attachment and biobehavioral catch-up. In: Berlin L, Ziv Y, Amaya-Jackson L, Greenberg MT, editors. Enhancing early attachments. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lindeheim O, Lewis E, Bick J, Bernard K, Peloso E. Effects of a foster parent training program on young children’s attachment behaviors: Preliminary evidence from a randomized clinical trial. Child and Adolescent Social Work. 2009;26:321–332. doi: 10.1007/s10560-009-0165-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Manni M, Gordon MK, Peloso E, Gunnar MR, Stovall-McClough KC, Eldreth D, Levine S. Foster children’s diurnal production of cortisol: An exploratory study. Child Maltreatment. 2006a;11:189–197. doi: 10.1177/1077559505285779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lewis E, Laurenceau J, Levine S. Effects of an attachment-based intervention on the cortisol production of infants and toddlers in foster care. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:845–859. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lindheim O, Gordon MK, Manni M, Sepulveda S, Ackerman J. Developing evidence-based interventions for foster children: An example of a randomized clinical trial with infants and toddlers. Journal of Social Issues. 2006b;62:767–785. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Stovall KC, Albus KE, Bates B. Attachment for infants in foster care: The role of caregiver state of mind. Child Development. 2001;72:1467–1477. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon RP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Lapsley A, Roisman GI. The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta-analytic study. Child Development. 2010;81:435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraiberg S. Clinical studies in infant mental health: The first year of life. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Garber BD. Attachment methodology in custody evaluation: Four hurdles standing between developmental theory and forensic application. Journal of Child Custody. 2009;6:38–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Fox NA, Drury S, Smyke AT, Egger HL, Nelson CA, Gregas MG, Zeanah CH. The validity of evidence-derived criteria for reactive attachment disorder: Indiscriminately social/disinhibited and emotionally withdrawn/inhibited types. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:216–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M, Endriga MC. Attachment security in preschoolers with and without externalizing problems: A replication. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman KE, Grossman K, Waters E, editors. Attachment from infancy to adulthood. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heller SS, Boris NW, Hinshaw-Fuselier SS, Page T, Koren-Karie N, Miron D. Reactive attachment disorder in maltreated twins: Follow-up from 18 months to 8 years. Attachment and Human Development. 2006;8:63–86. doi: 10.1080/14616730600585177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. The Adult Attachment Interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 552–598. [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. The importance of parenting in the development of disorganized attachment: Evidence from a preventive intervention study in adoptive families. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:263–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Promoting positive parenting: An attachment-based intervention. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Velderman M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH. Effects of attachment-based interventions on maternal sensitivity and infant attachment: Differential susceptibility of highly reactive infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006a;20:266–274. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein Velderman M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, van IJzendoorn MH, Mangelsdorf SC, Zevalkink J. Preventing preschool externalizing behavior problems through video-feedback intervention in infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006b;27:466–493. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Madsen S. Disruptions in attachment bonds: Implications for theory, research and clinical intervention. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Ghosh Ippen C, Van Horn P. Child-Parent Psychotherapy: 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:913–918. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000222784.03735.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Van Horn P. Don’t hit my mommy: A manual for Child–Parent Psychotherapy with young witnesses of family violence. Washington: Zero to Three Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Weston DR, Pawl JH. Preventive intervention and outcome with anxiously attached dyads. Child Development. 1991;62:199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindheim O, Dozier M. Caregiver commitment to foster children: The role of child behavior. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2007;31:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Bureau JF, Riley CD, Atlas-Corbett AF. Socially indiscriminate attachment behavior in the Strange Situation: Convergent and discriminant validity in relation to caregiving risk, later behavior problems, and attachment insecurity. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:355–372. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Jacobvitz D. Attachment disorganization: Genetic factors, parenting contexts, and developmental transformation from infancy to adulthood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 666–697. [Google Scholar]

- Macfie J, Fitzpatrick K, Rivas E, Cox M. Independent influences upon mother–toddler role reversal: Infant–mother attachment disorganization and role reversal in mother’s childhood. Attachment and Human Development. 2008;10:29–39. doi: 10.1080/14616730701868589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security of attachment in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 50. 1985. pp. 66–104. (–2, Serial No. 209) [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Solomon J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research and intervention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Powell B. The Circle of Security project: Attachment-based intervention with caregiver–preschool child dyads. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:107–124. doi: 10.1080/14616730252982491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough S. Interaction guidance: An approach for difficult-to-engage families. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J, Sarner L, Rosa L. Attachment therapy on trial: The torture and death of Candace Newmaker. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Stolk MN, van Zeijl J, Alink LRA, Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, et al. Extending the video-feedback intervention to sensitive discipline: The early prevention of anti-social behavior. In: Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, editors. Promoting positive parenting: An attachment-based intervention. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics and change. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miron D, Lewis M, Zeanah CH. Clinical use of observational procedures in early childhood relationship assessment. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Infant- mother attachment: Risk and protection in relation to changing maternal caregiving quality over time. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:38–58. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Marvin RS, Rutter M, Olrick J, Britner PA the ERAStudy Team. Child-parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:19–38. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Cooper G, Hoffman K, Marvin RS. The Circle of Security. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. 3rd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 450–467. [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi-Serpa C, Sancho Rossignol A, McDonough S. Video feedback in parent–infant treatments. Childand Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18:735–751. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers AH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Van Berckelaer-Onnes IA. Autism and attachment: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1123–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Colvert E, Kreppner J, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, et al. Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: Disinhibited attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]