Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Sjögren’s syndrome is a complex autoimmune disease of the salivary gland with an unknown etiology, so a thorough characterization of the transcriptome would facilitate our understanding of the disease. We use ultradeep sequencing of small RNAs from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and healthy volunteers, primarily to identify and discover novel miRNA sequences that may play a role in the disease.

METHODS

Total RNA was isolated from minor salivary glands of healthy volunteers and patients with either high or low salivary flow and sequenced on the SOLiD platform. Prediction of mature miRNAs from the sequenced reads was carried out using miRanalyzer, and expression was validated using Taqman qPCR assays.

RESULTS

We validated the presence of six previously unidentified miRNA sequences in patient samples and in several cell lines. One of the validated novel miRNAs shows promise as a biomarker for salivary function.

CONCLUSION

Sequencing small RNAs in the salivary gland is largely unprecedented, but here, we show the feasibility of discovering novel miRNAs and disease biomarkers by sequencing the transcriptome.

Keywords: next generation sequencing, Sjögren’s syndrome, microRNAs, novel miRNA discovery

Introduction

The ability to assay biological systems with high-throughput methods is widely seen as heralding a new age of biomedical research. As the latest addition to the high-throughput arsenal, next generation sequencing (NGS) is already being applied to study a variety of diseases. NGS offers the ability to sequence entire genomes or transcriptomes within days, but the analysis of large amounts of data generated can pose daunting informatics challenges. The main advantage of NGS over other high-throughput techniques, like microarrays, is the ability to mine for previously unknown sequences. However, owing to the relative novelty of NGS, there is little consensus on which methods are best and standardized analysis pipelines are slow to emerge (Oshlack et al, 2010). Despite these hurdles, NGS is already being successfully used to study a variety of biological systems and has been helpful in identifying markers for activity and progression (Maiden, 2000; Bertram et al, 2010; Ryu et al, 2011) in a variety of diseases.

One disease that could benefit from a thorough NGS study is Sjögren’s syndrome (SS). It is an autoimmune disorder mainly affecting exocrine glands that disrupts tear and saliva secretion, leading to symptoms of dry mouth and/or eyes. Histologically, SS is characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary and lacrimal glands, inducing an inflammatory response (Alevizos and Illei, 2010). As the etiology of Sjögren’s syndrome remains unclear and robust biomarkers are still unavailable, diagnosis can also be a problem.

More recently, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been investigated as potential biomarkers in SS (Alevizos et al, 2011). These short (18–24 bp) non-coding RNAs can cause silencing or degradation of mRNA, ultimately leading to a decrease in amount of protein, with or without changes in the number of mRNA transcripts. Owing to their small size and the imperfect binding paradigm, it is hypothesized that a single miRNA is used to regulate hundreds of transcripts simultaneously (Alevizos and Illei, 2010).

Here, we used NGS to characterize the small RNA population in minor salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients with the focus on microRNAs and we discovered several previously unidentified miRNAs. Specifically, we report the presence of six previously unidentified miRNAs in minor salivary glands and several cell lines.

Methods

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from minor salivary glands of patients with SS (n = 6) and healthy volunteers (n = 3) using the miRNeasy Mini Kit from Qiagen. All patients had low focus scores of 1–2 (on a scale of 0–12) and were divided in high and low salivary flow groups. Low flow was defined as unstimulated whole saliva flow rate of <1.5 ml/15 min and high salivary flow as unstimulated whole saliva flow rate of >1.5 ml/15 min. NGS was performed on pooled samples from three individuals in each group (high flow, low flow, and healthy volunteer). RNA quantity and quality was assessed by Nanodrop and Bioanalyzer. All patients with SS fulfilled European– American criteria for primary SS (Vitali et al, 2002). The Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research approved the study, and all subjects signed informed consent.

Deep sequencing of small RNAs

The RNA library preparation and the sequencing were performed on the SOLiD 4 platform from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) by EdgeBio (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Library preparation was according to manufacturer suggestions, using the small RNA library protocol provided with the SOLiD Total RNA-Seq kit (Applied Biosystems). Briefly, the RNA sample is enriched for miRNAs using the Invitrogen PureLink miRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The amount of small RNA is estimated based on Bioanalyzer data, and equal amounts of small RNA are loaded to be reverse transcribed into cDNA and amplified by PCR for 18 cycles. The amplified cDNA is then loaded onto templated beads, and nucleotides are read as the transcript elongates during emulsion PCR.

Data analysis

The SOLiD platform performs primary reconstruction from the individual reads and compiles the information as 35-bp-long sequences in colorspace with corresponding quality scores for each read. These were successively mapped to three sequence databases, where reads matched to one database were removed before moving on to the next step.

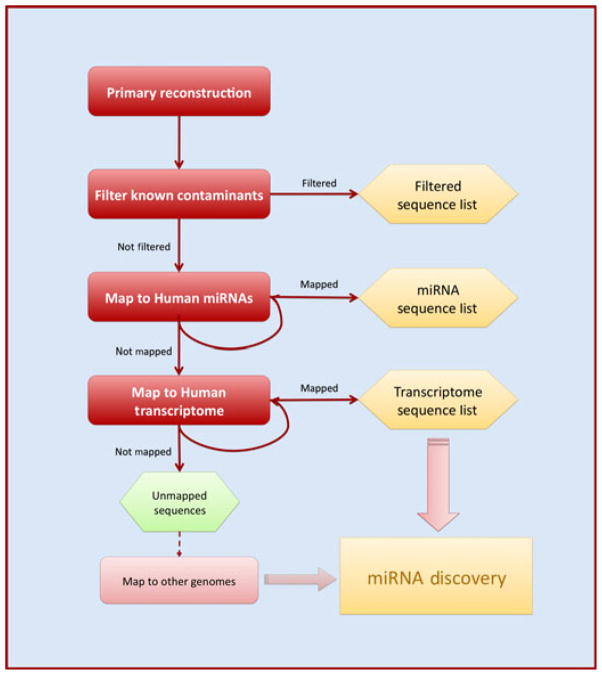

Figure 1 is a schematic of the analysis process. First, a filter database was used to remove known contaminant and highly common sequences, like rRNA and tRNA. Next, the sequences that passed through the filter were aligned to all known miRNA sequences from miRBase version 16 (Griffiths-Jones, 2004; Kozomara and Griffiths- Jones, 2011). Sequences not identified as known miRNAs were then aligned to the human genome (GrCH37/hg18) to find non-coding sequences to serve as candidates for novel miRNA discovery. Alignment and counting of unique reads were carried out using the Small RNA Analysis Pipeline Tool (RNA2MAP) from Applied Biosystems and custom Perl scripting.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the analysis pipeline. Sequenced reads are subsequently aligned to a database of filter sequences, known human miRNAs from miRBase, and finally the human genome. Of the genome-matched reads, sequences known to be part of the transcriptome can then be sorted and characterized, while the rest is used for novel miRNA predictions by miRanalyzer

Discovery of novel miRNAs

For discovery of previously unidentified miRNA sequences, we used the web-based tool miRanalyzer (Hackenberg et al, 2009). All unique reads that matched to the genome were counted and used as an input for miRanalyzer. The tool determines whether each sequenced read lies in an intergenic, intronic, or coding sequence to allow for comparison of the gene fragments found in each sample. Additionally, intergenic and intronic sequences are then considered for miRNA predictions. Using a multimodel, machine learning-based technique, miRanalyzer forms a consensus for each intergenic read based on mature and precursor sequences, including their folding and binding kinetics. Validated sequences were submitted to miRBase for confirmation and naming.

Validation of novel miRNAs by RT-PCR

The sequencing data were used to identify likely mature miRNA candidates, followed by qPCR to check for differential expression. To maximize the likelihood of identifying real novel miRNAs, sequences predicted by miRanalyzer were filtered by two criteria. Only miRNAs that were found in more than one sample or ones that had a matching predicted miRNA from the same precursor were kept. Expression of these selected sequences was validated using Taqman® qPCR assays from Applied Biosystems. Custom assays for novel miRNA sequences were created using the Custom Taqman® Assay Design Tool. RNU48 was used as a housekeeper sequence for each sample. Patient RNA samples that were pooled together for the sequencing were used as biological replicates.

Validation was also performed on cell lines in culture to check for expression in independent samples. The cell lines used were HSG (human salivary gland), Jurkat (human B cell), pHSG (primary culture of minor salivary glands from patient with SS), pFibroblast (primary culture of fibroblasts found in connective tissue around minor salivary gland of patient with SS).

Results

Summary of analysis process

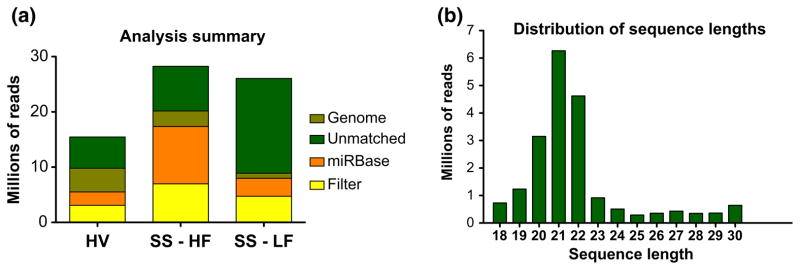

Figure 2a summarizes the distribution of matches in each step of the analysis. The number of total reads, as well as the reads mapped during each step of the analysis, varied greatly from sample to sample. This may be indicative of the fact that robust normalization needs to be performed before the samples can be compared. The length distribution of the data, however, has a clear peak at 21 nt, which is often seen in small RNA sequencing.

Figure 2.

(a) Number of reads that aligned to each subsequent database used in the analysis. (b) Histogram of lengths of sequenced reads before analysis, across all three samples. HV, healthy volunteer; SS-HF, SS patient with high salivary flow; SS-LF, SS patient with low salivary flow

Novel miRNA discovery

There were 121,148 (patient – high flow), 52,568 (patient – low flow), and 174,482 (Healthy Volunteer) unique reads that matched to the human genome. It is interesting to note that although the low flow sample had a high number of total reads, it had the least number of matches to the human genome.

These genome-matched reads and their counts were uploaded to miRanalyzer, which generated a total of 222 predicted mature miRNAs. Following the selection process described in the methods, we identified 15 candidates, shown in Table 1. Of these, about half had another miRNA predicted from the same precursor (mature–mature* pairs). The rest had only one mature miRNA predicted from a precursor, but it was found in more than one sample. Thus far, using the RNAs from individual patients that were pooled for NGS, we have validated the presence of six of these previously unknown miRNAs by Taqman qPCR: hsa-miR-4524b-3p, hsa-miR-4524b-5p, hsa-miR-5571-3p, hsa-miR-5571-5p, hsa-miR-5100, and hsa-miR-5572.

Table 1.

Summary of miRNA candidates selected for validation. Colored rows indicate miRNAs tested and validated by qPCR so far. Candidate-4 had reads matching to both positive and negative strands

| Selected miRNA candidates for validation

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel_ID | miRBase ID | Mature sequence | Precursor location |

| Matching miRNAs predicted on the same precursor | |||

| Candidate 1-3p | hsa-miR-4524b-3p | GAGACAGGTTCATGCTGCTA | chr17:67095683-67095797 |

| Candidate 1-5p | hsa-miR-4524b-5p | ATAGCAGCATAAGCCTGTCTC | |

| Candidate 2-3p | TCCACTGCCACTACCTAAT | chr7:134542275-134542377 | |

| Candidate 2-5p | ATTAGGTAGTGGCAGTGGA | ||

| Candidate 3-3p | hsa-miR-5571-3p | GTCCTAGGAGGCTCCTCTG | chr22:21558447-21558559 |

| Candidate 3-5p | hsa-miR-5571-5p | CAATTCTCAAAGGAGCCTCCC | |

| Candidate 4 (−) | AGACACACACATATATAGGTA | chr1:63610693-63610829 | |

| Candidate 4 (+) | TACCTATATATGTGTGTGTCT | ||

| Single unique miRNAs predicted in more than one sample | |||

| Candidate 5 | TCTGGCAGGGAGAAGAGCCCCT | chr5:111833616-111833724 | |

| Candidate 6 | TTTGGTGCACTGGCCGGGAAT | chr6:119008116-119008242 | |

| Candidate 7 | TAGCCAATTGTCCATCTTTA | chr8:125903374-125903508 | |

| Candidate 8 | CTACTAACCTGTGAAGTAGG | chrX:96207982-96208116 | |

| Candidate 9 | hsa-miR-5100 | TTCAGATCCCAGCGGTGCCTCT | chr10:42813017-42813135 |

| Candidate 10 | CCCGCCCCTCCGCGCCCCCCCCCC | chr19:13123543-13123645 | |

| Candidate 11 | hsa-miR-5572 | GTTGGGGTGCAGGGGTCTGCT | chr15:78660499-78660635 |

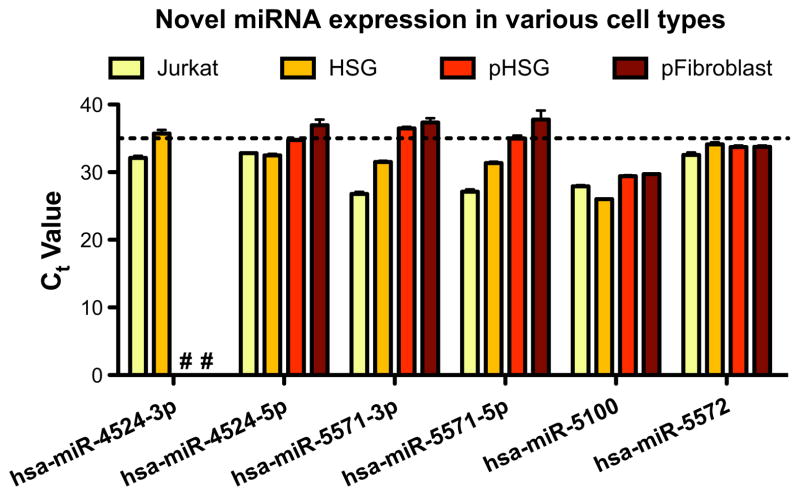

Additionally, we tested for the presence of these six miRNAs in four other types of cells: Jurkat (immortalized T lymphocyte), HSG (immortalized human salivary gland), pHSG (a primary cell line from a minor salivary gland biopsy), and pF (a primary cell line from oral fibroblasts). As Figure 3 shows, all six amplified in a reproducible way for Jurkat and HSG cell lines. hsa-miR-5100 and hsa-miR-5572 are also expressed in both primary minor salivary gland (pHSG) and fibroblast (pF) cell cultures. The 3p–5p pairs of hsa-mir-4524b and hsa-mir-5571 all amplified at Ct values of greater than or close to 35 cycles only in the pHSG and pF samples. The manufacturer documentation points out that the functional dynamic range of Taqman qPCR is under 35 cycles, and reliability of the measurement may become questionable at greater Ct values (Applied Biosystems, 2008). Despite high Ct values, however, they all amplified reproducibly (except for hsa-miR-4524b-3p), which may simply be indicative of low copy number (<10) in those particular sample types.

Figure 3.

Expression of validated novel miRNAs in different cell types. No amplification was seen for candidate-1-3p in either primary HSG or primary fibroblast cells (denoted by ‘#’). Ct values of greater than 35 cycles (dotted line) are often considered to be undetected. Jurkat, immortalized T-cell line; HSG, immortalized human salivary gland cell line; pHSG, primary culture of minor salivary gland from SS patient; pFibroblast, primary culture of fibroblasts from oral cavity of SS patient

Discussion

Though, still in its infancy, NGS offers an exciting and thorough way of characterizing the transcriptome of the cell. As the first attempt to characterize the transcriptome of SS using NGS, we were able to show the feasibility of finding previously unidentified small RNAs and test them for disease related activity.

Of the novel miRNAs that were discovered, two are particularly interesting. Alignment to the genome reveals that the precursor to hsa-miR-4524b-3p and hsa-miR-4524b-5p lies within an intron of the gene for ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 6 (ABCA6). Additionally, this gene lies within a cluster of five ABCA family genes on chromosome 17. Phylogenetic studies on this cluster found two important features: first, they concluded that intronic regions were more important than the exons in the evolution of all the genes in this cluster and, secondly, ABCA6 was one of only two genes in the cluster that were under strong positive selection (Li et al, 2007). As miRNAs are important in translational regulation, it would be likely that they are selected for. This supports the idea that hsa-miR-4524b-3p and hsa-miR-4524b-5p are likely to be genuine miRNAs.

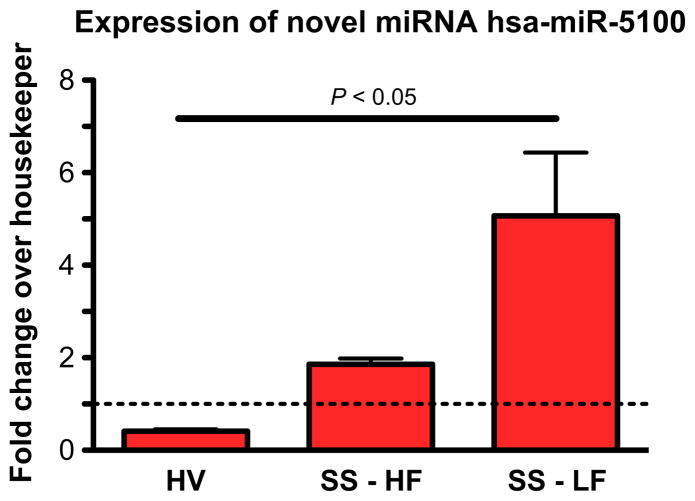

Another interesting previously unidentified miRNA is hsa-miR-5100. Not only this miRNA was amplified by qPCR in all tested samples, but it also is differentially expressed between patients and healthy volunteers. In fact, as shown in Figure 4, this miRNA seems to increase drastically as salivary flow decreases. According to miRBase, a very recent paper discovered a very similar sequence (two mismatches) in mouse B cells (Spierings et al, 2011). This newly found mouse miRNA, mmu-miR-5100, was found in B cells, so the correlation with an autoimmune disease like SS is intriguing. However, as all the patients were selected to have little to no lymphocytic infiltration, the increase in hsa-miR-5100 is more likely to be correlated with salivary dysfunction, not an increase in B cells. Although the origin of this miRNA needs to be further explored, it already seems to show disease specificity and a potential as a candidate prognostic marker.

Figure 4.

Differential expression of candidate-9 between healthy volunteers and SS patients. One-way ANOVA was performed with a Bonferroni s Multiple Comparison Test between HV and SS-LF. The dotted line represents the expression level of the housekeeper, RNU48. HV, healthy volunteer; SS-HF, SS patient with high salivary flow; SSLF, SS patient with low salivary flow

This is the first report of small RNA sequencing in SS, and we show that pooling of patient samples works well as an initial approach in a disease with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes. More detailed studies characterizing other non-coding small RNAs will enable us to create profiles that correlate with the functional status of the salivary gland. Given our previous work identifying microRNAs in saliva-derived exosomes (Michael et al, 2010), we are exploring the presence of the most promising miRNAs and non-coding RNAs in saliva, as it provides a non-invasive method for sample collection. We are encouraged with the identification of several previously unidentified miRNA sequences, and we aim to validate many, if not all, of the remaining candidates. NGS provides an exciting approach to disease characterization by searching for biomarkers within both known and unknown parts of the transcriptome.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDCR.

Footnotes

Author contribution

Mayank Tandon performed data analysis and edited the manuscript. Alessia Gallo performed sample preparation and validated the presence of novel miRNAs. Shyh-Ing Jang validated the presence of novel miRNAs Gabor G Illei and Ilias Alevizos designed the experiments and edited the manuscript.

References

- Alevizos I, Illei GG. MicroRNAs in Sjogren’s syndrome as a prototypic autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:618–621. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alevizos I, Alexander S, Turner RJ, Illei GG. MicroRNA expression profiles as biomarkers of minor salivary gland inflammation and dysfunction in Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:535–544. doi: 10.1002/art.30131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applied Biosystems. Guide to performing relative quantitation of gene expression using real-time quantitative PCR 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, Lill CM, Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease: back to the future. Neuron. 2010;68:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D109–D111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackenberg M, Sturm M, Langenberger D, Falcon-Perez JM, Aransay AM. miRanalyzer: a microRNA detection and analysis tool for next-generation sequencing experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W68–W76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D152–D157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Shi P, Wang Y. Evolutionary dynamics of the ABCA chromosome 17q24 cluster genes in vertebrates. Genomics. 2007;89:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden MC. High-throughput sequencing in the population analysis of bacterial pathogens of humans. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:183–190. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael A, Bajracharya SD, Yuen PS, et al. Exosomes from human saliva as a source of microRNA biomarkers. Oral Dis. 2010;16:34–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshlack A, Robinson MD, Young MD. From RNA-seq reads to differential expression results. Genome Biol. 2010;11:220. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S, Joshi N, McDonnell K, et al. Discovery of novel human breast cancer microRNAs from deep sequencing data by analysis of pri-microRNA secondary structures. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spierings DC, McGoldrick D, Hamilton-Easton AM, et al. Ordered progression of stage-specific miRNA profiles in the mouse B2 B-cell lineage. Blood. 2011;117:5340–5349. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-316034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554–558. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]