Abstract

We considered the functional role of control beliefs for cognitive performance by focusing on patterns of stability across multiple trials increasing in level of difficulty. We assessed 56 adults aged 18-88 on working memory tasks. We examined stability vs. lability (intraindividual variability, IIV) in control beliefs and the relationships with anxiety, distraction, and performance. Age was positively associated with IIV in control and performance, and IIV increased with task difficulty. Those maintaining stable control beliefs had better performance, and showed less anxiety and distraction. Those with lower stability and less control showed steeper declines in performance and increases in distraction. The findings suggest that stability of control beliefs may serve a protective function in the context of cognitively challenging tasks.

Keywords: control beliefs, intraindividual variability, working memory

General as well as domain and task-specific control beliefs are particularly relevant to understanding and predicting individual differences in age-related outcomes, such as physical health and cognitive functioning (Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2011). Consistent empirical findings have revealed that control beliefs play a protective role in adulthood and old age. Beliefs about control include expectancies about the degree of influence one has over health, memory, and aging-related changes in these and other domains. The main pattern emerging from the literature is that control beliefs decline with age, on average (Lachman & Firth, 2004; Lachman & Weaver, 1998; Mirowsky & Ross, 2007). Yet, there are individual differences and those who believe they have greater control over the outcomes have better health and cognitive performance. For instance, high control beliefs are associated with better health and lower risk for mortality (Infurna, Gerstorf, Ram, & Schupp, 2011; Surtees et al., 2010). Interestingly, recent longitudinal studies have shown that control beliefs serve more as a precursor than as a consequence of health across adulthood and old age (Infurna, Gerstorf, & Zarit, 2011), although there is also evidence for reciprocal change (Gerstorf, Röcke, & Lachman, 2011).

In the cognitive domain, people with high control beliefs perform better, are more likely to maintain their level of performance over time, and benefit more from cognitive training (e.g., Bagwell & West, 2008; Caplan & Schooler, 2003; Hertzog, Kramer, Wilson, & Lindenberger, 2008; Lachman, Andreoletti, & Pearman, 2006; Payne et al., 2012; Windsor & Anstey, 2008). There is also evidence that control beliefs have behavioral, motivational, cognitive, affective, and physiological consequences, which in turn impact health and cognitive functioning (Lachman et al., 2011; Miller & Lachman, 1999). For example, strategy use was identified as one mediator of the relationship between control and memory performance (Hertzog, McGuire, & Lineweaver, 1998; Lachman & Andreoletti, 2006). In addition, recent findings have provided evidence for the mediational role of state anxiety and distraction during a task (Lachman & Agrigoroaei, 2012). Lower levels of control beliefs were associated with higher state anxiety, which increased the likelihood of distracting thoughts during the tasks, which in turn was detrimental to memory performance.

Most of the past work on control beliefs and cognitive performance has focused on between-person differences in the level of control beliefs. An exception is the recent study focused on the within-person coupling of general control beliefs and cognitive performance in the context of daily repeated assessments (Neupert & Allaire, 2012). The results, obtained with a sample of older adults, revealed that control beliefs and cognitive performance covaried within people over time. In other words, on instances when general control beliefs were higher, cognitive performance was also higher and vice versa. These findings support the idea that, when interested in individual differences in cognitive performance, within-person trajectories in control beliefs provide additional information beyond between-person differences in level of control.

In the current study we extended the research on control beliefs and cognitive performance using a within-person approach and examining lability (i.e., within person variability) versus stability in the context of increasing cognitive challenge. We made the distinction between within person lability and stability (Nesselroade & Salthouse, 2004) in terms of degree of fluctuation in control beliefs across multiple trials and sessions of assessment.

Within-person fluctuations or lability, also known as intraindividual variability (IIV) or inconsistency, refer to within-person variability in a construct (e.g., performance) across multiple occasions and is considered separate from systematic or random errors of measurement. The general pattern emerging from the literature is that in the cognitive domain lower IIV is associated with better performance (Hultsch & MacDonald, 2004). With respect to control beliefs, there is evidence that higher fluctuation (lower stability) may itself be a warning sign or a possible risk factor. For instance, lower stability in control beliefs was shown to be a better predictor of mortality risk than one’s level of control (Eizenman, Nesselroade, Featherman, & Rowe, 1997). Importantly, there are individual differences in IIV which tend to be consistent and stable across tasks and time intervals (e.g., Hultsch & MacDonald, 2004).

Until now, the intraindividual study of control beliefs and cognitive performance has received limited attention. Our goal was to extend this line of research by using a design with repeated assessments across multiple sessions and trials. One of our main contributions, in comparison with past work, was that within each session, our cognitive tasks increased in level of difficulty. Past studies have suggested that increasing task difficulty could negatively affect task-specific beliefs, such as memory self-efficacy (Gardiner, Luszcz, & Bryan, 1997). Although perceived ability for a task would likely vary as a function of difficulty, theoretically beliefs about control ideally should remain constant across easy and difficult tasks (Lachman et al., 2011). In other words, maintaining a sense of control, despite the increasing level of difficulty, may be critical for mobilizing the motivational resources to tackle increased demands and performing well on cognitive tasks. Specifically, we expect volatile control beliefs, susceptible to the level of difficulty, to be a sign of maladaptive beliefs patterns, indicative of giving up or a helpless response to challenge. Similarly, we expect better cognitive performance for the participants who are more resilient in the face of challenges and show stable control beliefs despite greater difficulty. Although the majority of studies on IIV focused on the negative consequences of higher IIV, our focus was on the functional value of stability (lower IIV).

We expected higher stability of control beliefs across trials to be beneficial for memory performance. Yet, there are certain circumstances when higher stability in subjective control beliefs may be nonadaptive, and lead to negative outcomes. This is especially the case when circumstances do fluctuate in terms of objective levels of controllability. Along these lines, there is some evidence that in uncontrollable situations, those with higher control beliefs do worse, at least over the short run. For instance, Bisconti, Bergeman, and Boker (2006) found that recent widows with greater levels of perceived control over their social support had poorer overall adjustment across the first four months of widowhood.

However, in the context of the present study, performance in the cognitive test situation is objectively controllable through actions such as persistence, strategy use, or sustained attention. As Martin et al. (2012) have suggested, we can analyze the test situation by making the distinction between subjective evaluations and objective indicators of personal resources. In our case the amount of objective control over the situation was not varied. Therefore, ideally, in order to obtain good performance with increasing difficulty, subjective control beliefs over cognitive performance should be also stable, as these beliefs are known to affect effective use of strategies, anxiety, and task focus (Lachman & Agrigoroaei, 2012; Lachman & Andreoletti, 2006).

Another contribution of our study was that, for each level of task difficulty, we assessed, along with cognitive performance, task-specific measures of control beliefs. This allowed us to examine whether the previous findings showing within-person coupling between general control beliefs and cognitive performance in the context of daily assessments (Neupert & Allaire, 2012) would also be obtained using task-specific measures of control and memory tasks administered in the lab.

The main focus of the current study was on the amount of within-person variation in control beliefs, that is IIV, across increasing levels of cognitive task difficulty. IIV was expected to increase as the level of difficulty increases. Yet, there are individual differences in the stability of control beliefs over multiple trials and sessions and we investigated them in relation to memory performance, anxiety, and distraction. We hypothesized that those with lower IIV (i.e., higher stability) in control beliefs across increasing levels of task difficulty would perform better, improve more across sessions, and experience less anxiety and distraction during the tasks. Theoretically, the expected positive association between stability in control beliefs and cognitive performance should differ as a function of the level of control beliefs. Maintaining a lower versus a higher level of control beliefs across the easy and difficult levels of difficulty could lead to different levels of memory performance. Therefore, we explored whether the level of control played a moderator role.

As suggested by the literature, age represents a relevant source of individual differences in IIV, with older adults showing higher variability in cognitive performance, including memory (e.g., Hultsch, MacDonald, & Dixon, 2002; Sliwinski & Buschke, 2004). In addition, as indicated by Bielak et al. (2007), compared to younger adults, older adults show higher IIV in general control beliefs (e.g., locus of control). In line with the previous findings, we expected older adults to show greater IIV in control beliefs and memory performance. We also explored whether stability in control beliefs, irrespective of level, was beneficial in terms of memory performance, anxiety, and distraction to the same extent for people of different ages.

The Present Study

In this study we examined intraindividual variation in control beliefs across multiple sessions and trials characterized by an increasing level of cognitive task difficulty, in relation to cognitive performance, as well as anxiety and distraction. Our specific goals were the following:

Examine the within-person coupling between task-specific control beliefs and memory performance. We expected the trials with higher control beliefs to be characterized by better memory performance.

Analyze individual differences in IIV (lability vs. stability) in control beliefs and memory performance as a function of age and level of task difficulty. IIV was expected to be positively associated with age and level of task difficulty.

Examine the functional role of stability in control beliefs across increasing levels of task difficulty. Those with greater stability (i.e., lower IIV) were expected to perform better, improve more across sessions, and experience less anxiety and distraction during the tasks.

Explore the moderating role of age and average level of control beliefs to examine whether stable control beliefs in the face of increasing task difficulty were especially beneficial for a particular age group (younger vs. older) and/or for a particular level of control beliefs (lower vs. higher).

Method

Participants

The participants were 56 volunteers, aged 18 to 88 (M = 47.84; SD = 26.24) from a suburban area in the Eastern U.S. Some were students at a private university and others were volunteers from the community. The sample consisted of 64.3 % women and the average level of education in years was M = 15.73; SD = 2.78. The exclusion criteria were: having a stroke, serious head injuries, neurological disorders, or Parkinson’s disease, more than two errors on the Pfeiffer Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Pfeiffer, 1975), poor self-rated health, and learned English after age 10. We also excluded adults without a high school degree to be more comparable to the educational level of the college students.

Measures

Cognitive performance

We administered two working memory tasks: the n-back (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2009) and a memory updating numerical task (Schmiedek, Hildebrandt, Lövdén, Wilhelm, & Lindenberger, 2009; Schmiedek, Lövdén, & Lindenberger, 2010). Both tasks were computerized and implemented with DirectRT software.

N-back

Six levels of difficulty characterized by different levels of demand on working memory and speed of presentation were displayed sequentially in ascending order. The easiest level of this task (1-back) included 21 single digit numbers, from 0 to 9, displayed on the screen one at a time, for 2,000 ms., with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 500 ms. The participant’s task was to watch this series of numbers and press the space bar when the number currently on the screen was the same as the number that appeared one position back in the sequence (i.e., the previous number). Among the 20 potential targets (the first number cannot be a target since there is no previous number for it to match), there are four actual targets and two distracters (numbers which were seen recently but not exactly one back). For each participant we obtained the number of correct responses (i.e., responses corresponding to the actual targets) and the number of false alarms (all the other responses). For the 2-back, the participant’s task was to press the space bar when the number on the screen matched the number that appeared two positions back in the sequence. The 2-back contained 42 stimulus numbers, corresponding to 40 potential targets, eight actual targets, and four distracters. For the 3-back, the participant’s task was to respond when the number on the screen matched the number that appeared three positions back in the sequence. The 3-back contained 43 stimulus numbers, with 40 potential targets, eight actual targets, and four distracters.

The three levels (1-, 2-, and 3-back) were presented at two different speeds (slow: 2,000 ms. and fast: 1,000 ms.), resulting in six levels of difficulty: 1-back slow, 1-back fast, 2-back slow, and so on. The blank screen ISI was kept constant (500 ms.).

The final score at each level was the sensitivity measure A-prime (A’; Stanislaw & Todorov, 1999) calculated using the formula recommended by Snodgrass and Corwin (1988). Sensitivity is an index that reflects the ability to discriminate between targets and nontargets, by taking into account both the rate of correct responses and the rate of false alarms. The rate of correct responses was obtained by dividing the number of correct responses by the number of actual targets. The rate of false alarms was the ratio between the number of false alarms and the difference between the number of potential targets and the number of actual targets.

Memory updating numerical

There were eight levels of difficulty characterized by changes in number of stimuli and speed of presentation. The easiest level of this task starts with an image of two rows with two white boxes in each row, displayed on a black background. Each box in the first row contains a single digit number (0 to 9). The boxes in the second row are blank. After a display period (2,000 ms.), during which the participants have to memorize the numbers that are in the top row of boxes, the image disappears. Then, there is a 500 ms. ISI (blank screen). Following this, a series of addition and subtraction operations (e.g., −3, +6) appears one at a time in the bottom row of boxes. Participants must apply the operation to the number that was previously in the box above it. One operation is applied to each of the boxes, in random order. After this, a second round of operations is applied, during which the participant must remember the results from the operation previously applied and apply a new addition or subtraction operation to these intermediate results. After two rounds of operations have been applied to all of the boxes, a screen appears with only the top row of blank boxes and an arrow pointing to the first box in the row. The participant must type the number he or she calculated from the two operations applied. This is repeated for each of the boxes in the row.

Task difficulty was increased, by decreasing the length of time the operations were displayed (from 2,000 to 1,000 ms.) and by increasing the number of boxes in each row (from two to three, four, and five). All participants were presented with 16 sets of boxes: two sets at each level (two, three, four, or five boxes) in the slow condition, and two sets at each level in the fast condition. The sets were given in order beginning with the slow condition for two boxes, then the fast condition for two boxes, followed by the slow condition for three boxes, and so on. The operations were randomly selected and consisted of adding or subtracting a single digit, ranging from 0 to 9, with the restriction that all intermediate and final results were positive single digit numbers. The blank screen ISI was kept constant (500 ms.).

The final score at each level was the proportion of correct responses over the two sets at each level.

Test-specific questions

Control Beliefs

Before starting the tasks, for both working memory measures, at each level of difficulty, participants were asked about their level of control beliefs: “how much control do you think you will have over your performance on this task?”. Participants rated their level of control on a scale ranging from 1 (no control) to 5 (complete control).

After completing each level of difficulty, for both working memory measures, participants rated their level of anxiety and distraction.

Perceived anxiety

The question was “please rate how anxious you were feeling during the last task” and the response scale ranged from 1 (not at all anxious) to 5 (very anxious).

Perceived distraction

Participants were asked: “how much were you distracted during the task?”. The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely).

Procedure

We used a short-term multi-occasion design which required participants to come to the lab for four in-person sessions, scheduled approximately one week apart. The average intervals, in days, between the sessions were: sessions one and two 10.33 (SD = 5.44), sessions two and three 10.79 (SD = 6.12), sessions three and four 10.73 (SD = 8.27). At each session, the two working memory tasks were administered. The order of these two tasks was counterbalanced across participants but kept constant across sessions, for each participant. For both tasks, the order did not impact the level of performance. Both working memory tasks started at the easiest level of difficulty that is the minimum number of stimuli (i.e., two frames, 1-back) presented at the slowest speed (2,000 ms.). As the level of task difficulty increased, participants were informed about the changes in the speed of presentation (e.g., for memory updating: “In a moment you will do another set of addition and subtraction with two boxes that will be presented at a faster pace than the previous one”) and the number of stimuli (e.g., “In a moment you will do another set of addition and subtraction, this time with three boxes”). For both tasks, the increase in the number of stimuli was explained with an example.

Prior to each difficulty/speed level, the participants estimated how much control they expected to have. After each difficulty/speed level the participants rated their level of anxiety and distraction during the task.

Data Analysis

We created a continuous index of difficulty for each of the working memory measures based on the level of task demand on working memory (i.e., 1, 2, and 3 digits for n-back and 2, 3, 4, and 5 boxes in each row for memory updating) and speed of each trial (i.e., slow and fast). The least difficult trial consisted of the first level of task demand and the slowest speed. The next difficult rating was the faster speed within the same level of task demand. Subsequent difficulty ratings were created in the same fashion. Difficulty ranged from 1-8 (4 levels of task demand, 2 speeds) for memory updating and from 1-6 (3 levels of task demand, 2 speeds) for the n-back1.

Given the structure of the data [measures (6 trials for n-back and 8 trials for memory updating) nested within sessions (4), and nested within participants (56)], the hypotheses were tested using multilevel models. Prior to conducting analyses to address the main research questions, a preliminary analysis examined whether the two working memory measures, n-back and memory updating, could be combined an indicators of one measure. Results of a multilevel model testing for a within-person relationship between n-back and memory updating revealed that the relationship was significant (γ10 = .02, t = 2.39, p = .017), but the amount of shared variance was very low (1.3%). Thus, subsequent analyses were conducted for n-back and memory updating separately. In this study, sex and educational attainment were not significantly associated with the dependent variables (i.e., memory performance, anxiety, and distraction) and therefore were not included as covariates in the models.

For both the n-back and memory updating tasks we created an index of IIV for each participant by using within-person standard deviations2 (Neupert, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2008) across all trials. For our analyses, the index of IIV was considered as a between-person variable, with one exception. To address the association between task difficulty and IIV we used a two-level model in which IIV was operationalized as the Level 1 residual variance term (Hoffman, 2007). The example with memory performance as an outcome is illustrated below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Between-person means and standard deviations for the study variables, as well as their intercorrelations, are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations between the Study Variables.

| Mean | SD | Age | Sex | Education | Control Beliefs | Memory Performance |

Perceived Anxiety |

Perceived Distraction |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | IIV | Level | IIV | Level | Level | |||||||

| Age | 47.84 | 26.24 | -- | |||||||||

| Sex | -- | -- | −.05 | -- | ||||||||

| Education (years) |

15.73 | 2.78 | .58*** | −.25 | -- | |||||||

| Control Beliefs |

Level |

3.63 3.20 |

.86 .98 |

−.26

−.44 ** |

−.28* −.24 |

−.001 −.08 |

(.87***) | |||||

| IIV |

.69 .72 |

.35 .29 |

.44

**

.37 ** |

.01 −.04 |

.28* .24 |

−.39

**

−.29 * |

(.67***) | |||||

| Memory Performance |

Level |

.91 .71 |

.06 .16 |

−.24

−.36 ** |

−.20 −.23 |

.02 .05 |

.33* .35** |

−.07 −.17 |

(.67***) | |||

| IIV |

.10 .25 |

.05 .07 |

.43

**

.35 ** |

.19

.29 * |

.24 .08 |

−.25

−.34 * |

.30* .30* |

−.92

***

−.66 *** |

(.49**) | |||

| Perceived Anxiety |

Level |

1.83 1.96 |

.59 .60 |

.30* .34* |

−.06 −.01 |

.06 .15 |

−.68

***

−.65 *** |

.36** .15 |

−.30* −.19 |

.37** .20 |

(.89***) | |

| Perceived Distraction |

Level |

1.68 1.60 |

.58 .57 |

−.30* −.14 |

.07 .09 |

−.16 −.13 |

−.38

**

−.40 ** |

.12 −.01 |

−.24

−.28 * |

.26 .19 |

.46

***

.53 *** |

(.84***) |

Notes: SD = standard deviation; IIV = intraindividual variability; Sex: 1 = male; 2 = female; the values in italics correspond to the n-back variables; the values in bold correspond to memory updating variables; on the diagonal, the values in parentheses correspond to the correlations between n-back and memory updating for each of the six variables of interest: level of control beliefs, IIV in control beliefs, level of memory performance, IIV in memory performance, level of perceived anxiety, and level of perceived distraction.

p< .001

p< .01

p< .05

Partitioning Variance

Fully unconditional multilevel models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) were conducted to partition the variance across levels in the dependent variables. Because we had trials within sessions and within persons, we first tested to see whether a 2-level (trial within person) or 3-level (trial within session within person) nesting structure was appropriate. Across all variables, there was no significant variance at the level of session (ps >.12). Therefore, all multilevel analyses were conducted with trial as Level 1 and persons as Level 2 because significant variance was observed for all variables at both levels. An example of equations used for the unconditional multilevel models can be represented as:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Equation 5 indicates that performance for person i on trial t is a function of an individual intercept (β0) and the extent to which individuals deviate from their own intercept (r). The individual intercepts become the outcome variable in Equation 6 where they are a function of a sample-level grand intercept (γ00) and the extent to which each individual deviates from the sample-level average (u). The deviations from individual intercepts (Level 1) and the sample-level average (Level 2) are used to calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient, representing the amount of variance in the dependent variable that is found at each level. Results from the unconditional models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Percentages of Within-person and (Between-person) Variances Obtained using the Unconditional Models, for the Measures Associated with both Working Memory Tasks.

| Working Memory Task |

Control Beliefs |

Memory Performance |

Perceived Anxiety |

Perceived Distraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-back | 45% (55%) | 79% (21%) | 59% (41%) | 64% (36%) |

| Memory updating |

39% (61%) | 74% (26%) | 60% (40%) | 62% (38%) |

Within-person Coupling between Control Beliefs and Memory Performance

Within-person coupling models (see Equations 7-11 below) revealed significant positive associations between within person variations in control beliefs and within person variations in memory performance when controlling for practice (Session), learning (Session*Session), as well as for age and average level of control, for both n-back (γ10 = .08, t = 13.57, p <.001) and memory updating (γ10 = .18, t = 18.23, p <.001).

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

The Association between Age and Intraindividual Variability in Control Beliefs and Memory Performance

Correlations of the indexes of IIV across all trials with age (Table 1) showed that older adults were more variable in control beliefs [n-back: r (54) = .44, p = .001; memory updating: r(54) = .37, p = .005] and performance [n-back: r(52) = .43, p = .001; memory updating: r(54) = .35, p = .007], as predicted.

The Association between Task Difficulty and Intraindividual Variability in Control Beliefs and Memory Performance

The results revealed significant positive associations between task difficulty and IIV, for both control beliefs (memory updating: α1 = .05, z = 3.30, p =.001, n-back: α1 = .19, z = 8.03, p < .001) and memory performance (memory updating, α1= .06, z = 4.21, p < .001,, n-back: α1 = .56, z = 23.54, p <.001).

The Association between Stability in Control Beliefs across Task Difficulty and Memory Performance, Anxiety, and Distraction

To examine the potential benefit of stability of control, in contrast to lability, across levels of task difficulty, a multilevel model was conducted with performance as the dependent variable, age and a person-level indication of variability in control across trials as independent variables, individual average in control as a person-level covariate, difficulty as a trial-level independent variable, and IIV Control × Difficulty as a cross-level interaction term (see Equations 12-14 below). Across all multilevel models, predictors at Level 2 were centered around the grand mean.

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

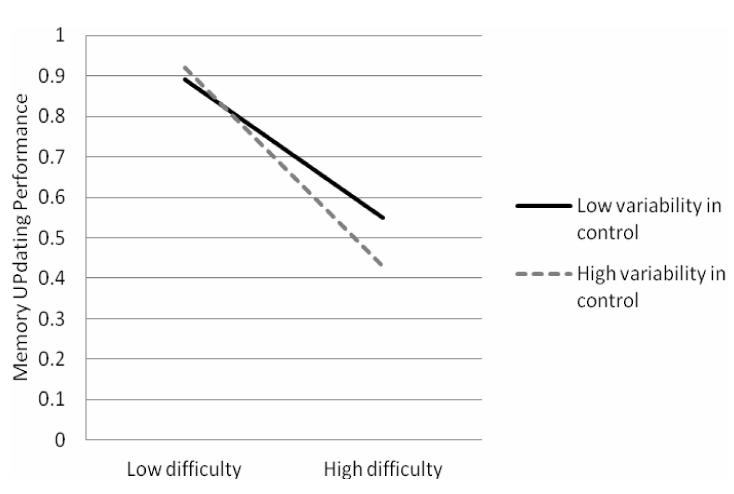

Results for both models (see Table 3) with the n-back and memory updating task revealed a significant interaction. In line with our hypothesis, there was a significant IIV Control × Difficulty interaction on performance. Figure 1 shows that people who were more variable in their control beliefs (one standard deviation above the sample mean in variation) had a stronger relationship between difficulty and performance compared to those with low variability in their control (one standard deviation below the mean in variability). This indicates that people who were more stable (i.e., less variable) in their beliefs were able to maintain higher levels of performance as difficulty increased compared to those who were less stable (i.e., more variable). The pattern for the n-back was similar. In addition, n-back memory performance was positively associated with the individual average of control beliefs. Further analyses revealed that these presented patterns did not differ by age.

Table 3. Unstandardized Estimates (and Standard Errors) of Multilevel Models Predicting Working Memory Performance.

| Fixed Effects | N-back | Memory updating |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept, γ00 | 1.07***(.01) | 1.04***(.02) |

| IIV Control, γ03 | .09**(.03) | .14(.09) |

| Difficulty, γ10 | −.04***(.001) | −.07***(.002) |

| Age, γ01 | −.001(.0003) | .−.002 (.0009) |

| Average Control, γ02 | .02* (.01) | .04 (.02) |

| IIV Control × Difficulty, γ11 | −.02***(.004) | −.03***(.007) |

|

| ||

| Random Effects | ||

| Level 2 (τ00) | .003*** | .02*** |

| Level 1 (σ2) | .01*** | .04*** |

| R2 (Level 1) | .78 | .43 |

| R2 (Level 2) | 0 | .10 |

p< .001

p< .01

p< .05

R2 values were calculated using pseudo R2 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002)

Figure 1.

Results of the Difficulty × Variability in Control interaction on performance of the memory updating task

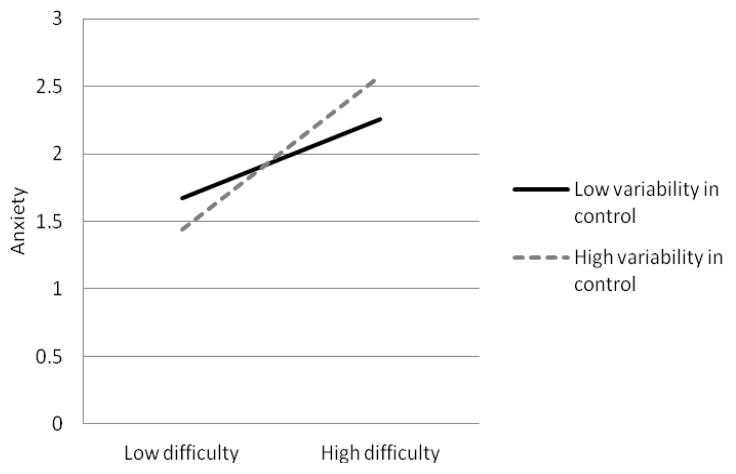

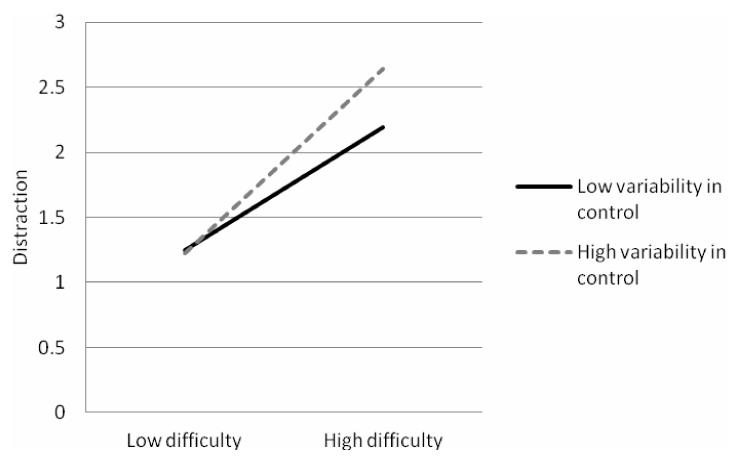

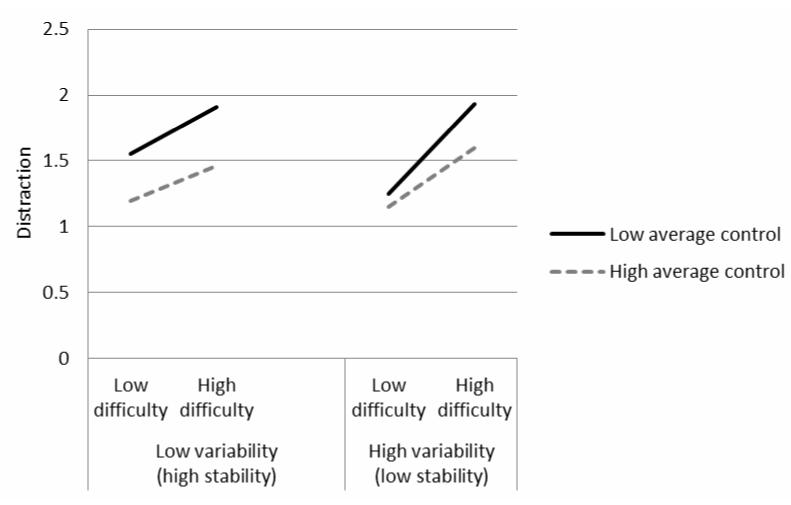

We also examined whether variability in control would interact with difficulty when predicting anxiety, distraction, and changes in performance across sessions. The models for anxiety and distraction were the same as the one depicted in Equations 12-14 but with different dependent variables (see Table 4). There was a significant IIV Control × Difficulty interaction on anxiety for both the memory updating task and the n-back (see Figure 2). Results for both tasks suggest that people who were more stable in their beliefs showed less increase in anxiety as difficulty increased compared to those who were less stable in their beliefs. There was also a significant IIV Control × Difficulty interaction on distraction for both the memory updating task and the n-back (see Figure 3). Results for both tasks suggest that people who were more stable in their beliefs showed less increase in distraction as difficulty increased compared to those who were less stable in their beliefs. To examine changes in performance across sessions, session was included as a trial-level predictor at Level 1 and a 3-way interaction of Session × IIV Control × Difficulty was tested (see Table 5). The 3-way interaction was not significant for memory updating or the n-back. For memory updating, there was a significant positive association between session and performance, suggesting within-person increases in memory performance across sessions. Interestingly, the same association was in the negative direction for the n-back task. However, additional between-person analyses revealed that, on average, memory performance increased across sessions, for both tasks.

Table 4. Unstandardized Estimates (and Standard Errors) of Multilevel Models Predicting Anxiety or Distraction.

| N-back | Memory updating | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Anxiety | Distraction | Anxiety | Distraction |

| Intercept, γ00 | 1.18***(.07) | 1.15***(.08) | 1.44***(.07) | 1.21***(.08) |

| Age, γ01 | .0002 (.003) | −.01** (.003) | .002 (.003) | −.01** (.003) |

| IIV Control, γ03 | −.89*** (.22) | −.11 (.25) | −.49 (.26) | −.60* (.28) |

| Difficulty, γ10 | −.19***(.01) | .15*** (.01) | .12***(.01) | .09***(.01) |

| Average Control, γ02 | −.43***(.07) | −.30**(.09) | −.39***(.07) | −.33***(.08) |

| IIV Control × Diff., γ11 | .29***(.03) | .11***(.03) | .08**(.02) | .12***(.02) |

|

| ||||

| Random Effects | ||||

| Level 2 (τ00) | .18*** | .22*** | .20*** | .23*** |

| Level 1 (σ2) | .34*** | .47*** | .44*** | .45*** |

| R2 (Level 1) | .28 | .13 | .15 | .09 |

| R2 (Level 2) | .46 | .30 | .42 | .25 |

p< .001

p< .01

p< .05

R2 values were calculated using pseudo R2 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002)

Figure 2.

Results of the Difficulty × Variability in Control interaction on anxiety for the memory updating task

Figure 3.

Results of the Difficulty × Variability in Control interaction on distraction for the n-back task

Table 5. Unstandardized Estimates (and Standard Errors) of Multilevel Models Predicting Change in Performance.

| Fixed Effects | N-back | Memory updating |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept, γ00 | 1.10***(.01) | 1.00***(.03) |

| Age, γ01 | −.001 (.0003) | −.002 (.001) |

| IIV Control, γ03 | .11 (.045) | .12 (.12) |

| Difficulty, γ10 | −.06***(.003) | −.08***(.01) |

| Session, γ20 | −.01**(.005) | .02*(.01) |

| Average Control, γ02 | .02*(.001) | .04(.02) |

| IIV Control × Difficulty, γ11 | −.03**(.01) | −.03(.02) |

| IIV Control × Session, γ21 | −.01(.01) | .01(.03) |

| Difficulty × Session, γ30 | .002(.003) | .002(.005) |

| IIV Control × Difficulty × Session, γ31 | .006(.004) | −.001(.01) |

|

| ||

| Random Effects | ||

| Level 2 (τ00) | .003*** | .02*** |

| Level 1 (σ2) | .007*** | .04*** |

| R2 (Level 1) | .46 | .44 |

| R2 (Level 2) | .00 | .06 |

p< .001

p< .01

p< .05

R2 values were calculated using pseudo R2 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002)

Additional models were conducted to examine if stability in beliefs across increasingly difficult levels of cognitive tasks was more important in terms of anxiety, distraction, and performance for someone who has a low average level of beliefs compared to someone with a high average. An IIV Control × Difficulty × Individual Average Control cross-level interaction was tested with anxiety, distraction, and performance as dependent variables for both the n-back and memory updating tasks (see Equations 15-17 below).

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

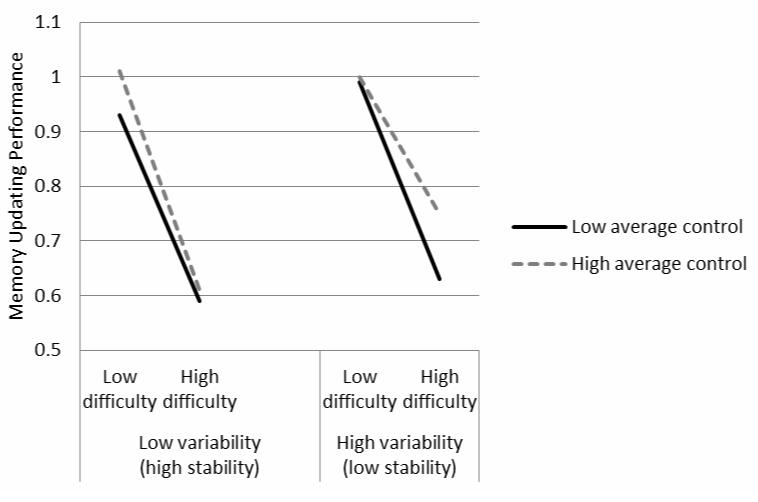

Results for the n-back revealed that this interaction was not significant for anxiety (γ13 = .004, t = .11, p = .91), distraction (γ13 = .03, t = .70, p = .48), or performance (γ13 = .0001, t = −0.01, p = .99). However, results for the memory updating task revealed that the interaction was significant for performance (γ13 =.02, t = 3.21, p = .001, see Figure 4), and distraction (γ13 = −.06, t = −2.40, p = .02, see Figure 5), but not anxiety (γ13 = −.03, t = −1.33, p = .18). We created Figures 4 and 5 by conducting separate models for those below and above the median in variability in control. Figure 4 indicates that the decrease in performance with increasing difficulty is similar for individuals with low variability (high stability) for low and high individual average control (the Difficulty × Individual Average Control interaction was not significant: γ12 = .004, t = 1.23, p = .22). For those with high IIV, those with low average control experienced a steeper decline in performance with increasing difficulty compared to those with high average control (the Difficulty × Individual Average Control interaction was significant: γ12 = .02, t = 5.71, p < .001). Figure 5 indicates that for those with low IIV control, the increase in distraction with increase in difficulty is similar across individual average levels of control (the Difficulty × Individual Average Control interaction was not significant: γ12 = −.01, t = −1.55, p = .12). Among those with high IIV control, those with low average control experienced a steeper increase in distraction with increases in difficulty compared to those with high average control (the Difficulty × Individual Average Control interaction was significant: γ12 = −.04, t = −3.87, p < .001).

Figure 4.

Results of the Variability in Control × Difficulty × Individual Average Control interaction on performance of the memory updating task

Figure 5.

Results of the Variability in Control × Difficulty × Individual Average Control interaction on distraction of the memory updating task

Discussion

The main goal of the current study was to analyze interindividual differences in the lability vs. stability of control beliefs across multiple trials and sessions and examine its association with memory performance, anxiety, and distraction, in younger and older adults. Our results support the assertion that IIV contains meaningful information beyond that contained in mean levels (Hultsch & MacDonald, 2004). As expected, older adults showed higher IIV in control beliefs and performance and greater IIV was obtained on more difficult trials. However, irrespective of the level of control, those who maintained stable control beliefs in the face of difficult tasks performed better and showed less anxiety and distraction during the task. These patterns were obtained for both working memory tasks, irrespective of age. In addition, for the memory updating numerical task, among the participants with lower stability in control beliefs, those with lower average levels of control showed steeper declines in memory performance as a function of difficulty and steeper increases in distraction during the task. Overall, our findings highlight the adaptive value of stability of control beliefs in the context of challenging cognitive tasks.

The stability of control beliefs has been associated with positive outcomes such as a lower mortality risk (Eizenman et al., 1997). In the present study we focused on the adaptive value of short-term stability in contrast to lability of control beliefs in relation to memory performance on tasks varying in difficulty across multiple trials and sessions. The findings suggest that stability may serve as a resource or source of resilience with regard to working memory.

In the present study we examined IIV in control beliefs using task-specific measures and found the results to be consistent across adulthood. Another feature was the use of working memory tasks with multiple trials corresponding to increasing levels of difficulty. Therefore, our findings represent a valuable additional step in understanding the role of control beliefs variability in accounting for individual differences in cognitive performance. It is not just level of control that is positively related to performance, as found in the majority of the previous studies, using a between-person approach. We demonstrate that lower stability in control is detrimental to performance regardless of level of control. Those who report having as much control over difficult trials as they do over easy trials perform better and experience less anxiety and distraction during the tasks. On the other hand, those with unstable control beliefs display worse outcomes. Therefore, stability in control beliefs may be considered an indicator of resilience in the face of challenging cognitive tasks. Level of control beliefs is positively associated with performance. Yet, difficult tasks may lead some to give up and feel they are not in control. Such fluctuation can have damaging consequences for performance because it is precisely in the most challenging situations that a strong sense of control can be critical for maintaining motivation and persistence (Lachman et al., 2011). If subjective control varies as a function of experience rather than being a stable expectancy it seems to play a negative functional role for performance.

Together, these results emphasize that in the domain of memory functioning, stability in subjective control beliefs is associated with better objective memory performance and may serve a protective function in the face of challenging tasks. The protective role of control beliefs was also highlighted in previous work by Neupert and Allaire (2012), using general measures of control among older adults, in the context of daily repeated assessments. Their results showed that control beliefs and cognitive performance covaried within individuals across occasions. In our study we replicated these findings, this time by using task-specific measures of control beliefs over cognitive performance, in the lab.

The study has some limitations that should be considered in drawing conclusions. Our participants were on average highly educated adults (M = 15.73 years), which can affect the generalizability of our findings to those with less education. In addition, the measures of control, anxiety, and distraction were based on single items. Another potential limitation can be related to the relatively small sample size. However, the short-term multi-occasion design that we used allowed us to obtain a large number of data points (i.e., 1,344 observations for n-back task and 1,792 for memory updating).

Despite these limitations, our findings have practical and theoretical implications. Intervention efforts aimed at increasing cognitive performance could potentially create opportunities for individuals to maintain consistent feelings of control even in the face of difficult tasks. Based on the current study, maintaining consistent feelings of control is adaptive for cognitive functioning and may be considered a form of resilience. Future work is necessary to identify what factors account for individual differences in control beliefs stability. It will also be of interest to examine multidirectional and lagged models to understand the processes of change and maintenance of control beliefs in relation to performance. Further work will also be needed to examine the mediational processes. In the present study we examined anxiety and distraction in separate models, and it will be of interest to examine within-person variation in these variables as possible mediators in relation to control beliefs and performance. Such work will enable us to examine how stable control beliefs may play a functional role for memory aging.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging grant RO1 AG 17920.

Footnotes

For both tasks, the expected levels of difficulty were consistent with memory performance. On average, the level of memory performance decreased as a function of increasing level of difficulty. There was one exception: for the memory updating task, performance at the second level of difficulty [2 boxes/fast (M = .8728)] was slightly lower than performance at the third level of difficulty [3 boxes/slow (M = .8795)].

We also computed coefficients of variation (Hultsch, Strauss, Hunter, & MacDonald, 2008) where the within-person standard deviations were divided by each participant’s own mean. Correlations revealed that the within-person standard deviations were highly related to the coefficients of variation (e.g., variability in control for the n-back, r = .91, p <.001; variability in control for the memory updating task, r = .82, p <.001). We report results using the within-person standard deviations. In addition, given that within individuals the trials vary in terms of level of difficulty and occasion of measurement (i.e., session), we computed an alternative index of IIV based on the absolute values of residuals (Röcke, Li, & Smith, 2009) after regressing control beliefs on level of difficulty and session. This indicator of IIV, which was adjusted for systematic trends in the data, was used to retest all our models and the same patterns of results were obtained.

References

- Bagwell DK, West RL. Assessing compliance: Active versus inactive trainees in a memory intervention. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2008;3:371–382. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1413. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielak AAM, Hultsch DF, Levy-Ajzenkopf J, MacDonald SWS, Hunter MA, Strauss E. Short-term changes in general and memory-specific control beliefs and their relationship to cognition in younger and older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2007;65:53–71. doi: 10.2190/G458-X101-0338-746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS, Boker SM. Social support as a predictor of variability: An examination of the adjustment trajectories of recent widows. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:590–599. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan LJ, Schooler C. The roles of fatalism, self-confidence, and intellectual resources in the disablement process in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:551–561. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.551. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizenman DR, Nesselroade JR, Featherman DL, Rowe JW. Intraindividual variability in perceived control in an older sample: The MacArthur successful aging studies. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:489–502. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.3.489. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner M, Luszcz MA, Bryan J. The manipulation and measurement of task-specific memory self-efficacy in younger and older adults. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21:209–227. doi: 10.1080/016502597384839. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Röcke C, Lachman ME. Antecedent-consequent relations of perceived control to health and social support: Longitudinal evidence for between-domain associations across adulthood. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2011;66B:61–71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq077. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Kramer AF, Wilson RS, Lindenberger U. Enrichment effects on adult cognitive development. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2008;9:1–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01034.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, McGuire CL, Lineweaver TT. Aging, attributions, perceived control, and strategy use in a free recall task. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 1998;5:85–106. doi: 10.1076/anec.5.2.85.601. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L. Multilevel models for examining individual differences in within-person variation and covariation over time. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:609–629. [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch DF, MacDonald SWS. Intraindividual variability in performance as a theoretical window onto cognitive aging. In: Dixon RA, Bäckman L, Nilsson L-G, editors. New Frontiers in Cognitive Aging. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch DF, MacDonald SWS, Dixon RA. Variability in reaction time performance of younger and older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B:P101–P115. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.p101. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.P101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch DF, Strauss E, Hunter MA, MacDonald SWS. Intraindividual variability, cognition, and aging. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The Handbook of Aging and Cognition. 3rd ed. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 491–556. [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Ram N, Schupp J. Long-term antecedents and outcomes of perceived control. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:559–575. doi: 10.1037/a0022890. doi: 10.1037/a0022890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Zarit SH. Examining dynamic links between perceived control and health: Longitudinal evidence for differential effects in midlife and old age. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:9–18. doi: 10.1037/a0021022. doi: 10.1037/a0021022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Agrigoroaei S. Low perceived control as a risk factor for episodic memory: The mediational role of anxiety and task interference. Memory and Cognition. 2012;40:287–296. doi: 10.3758/s13421-011-0140-x. doi: 10.3758/s13421-011-0140-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Andreoletti C. Strategy use mediates the relationship between control beliefs and memory performance for middle-aged and older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2006;61B:P88–P94. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.p88. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.P88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Andreoletti C, Pearman A. Memory control beliefs: How are they related to age, strategy use and memory improvement? Social Cognition. 2006;24:359–385. doi: 10.1521/soco.2006.24.3.359. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Firth KMP. The adaptive value of feeling in control during midlife. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2004. pp. 320–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Neupert SD, Agrigoroaei S. The relevance of control beliefs for health and aging. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of aging. Academic Press; Burlington, MA: 2011. pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. Sociodemographic variations in the sense of control by domain: Findings from the MacArthur studies of midlife. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13:553–562. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Schneider R, Eicher S, Moor C. The Functional Quality of Life (fQOL)-Model: A new basis for quality of life-enhancing interventions in old age. The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;25:33–40. doi: 10.1024/1662-9647/a000053. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LMS, Lachman ME. The sense of control and cognitive aging: Toward a model of mediational processes. In: Hess TM, Blanchard-Fields F, editors. Social cognition and aging. Academic Press; New York: 1999. pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Life course trajectories of perceived control and their relationship to education. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1339–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR, Salthouse TA. Methodological and theoretical implications of intraindividual variability in perceptual-motor performance. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B:P49–P55. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.p49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Allaire JC. I think I can, I think I can: Examining the within-person coupling of control beliefs and cognition in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0026447. doi: 10.1037/a0026447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Mroczek DK, Spiro A. Neuroticism moderates the daily relation between stressors and memory failures. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:287–296. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.287. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BR, Jackson JJ, Hill PL, Gao X, Roberts BW, Stine-Morrow EAL. Memory self-efficacy predicts responsiveness to inductive reasoning training in older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2012;67B:27–35. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr073. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Röcke C, Li S-C, Smith J. Intraindividual variability in positive and negative affect over 45 days: Do older adults fluctuate less than young adults? Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:863–878. doi: 10.1037/a0016276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Jogia J, Fast K, Christodoulou T, Haldane M, Kumari V, Frangou S. No gender differences in brain activation durint the N-back task: An fMRI study in healthy individuals. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:3609–3615. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20783. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F, Hildebrandt A, Lövdén M, Wilhelm O, Lindenberger U. Complex span versus updating tasks of working memory: The gap is not that deep. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009;35:1089–1096. doi: 10.1037/a0015730. doi: 10.1037/a0015730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedek F, Lövdén M, Lindenberger U. Hundred days of cognitive training enhance broad cognitive abilities in adulthood: Findings from the COGITO study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2010;2:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00027. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski M, Buschke H. Modeling intraindividual cognitive change in aging adults: Results from the Einstein Aging Studies. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2004;11:196–211. doi: 10.1080/13825580490511080. [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Corwin J. Pragmatics of measuring recognition memory: Applications to dementia and amnesia. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1988;117:34–50. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.117.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanislaw H, Todorov N. Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1999;31:137–149. doi: 10.3758/bf03207704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees PG, Wainwright WJ, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Bingham S, Khaw K-T. Mastery is associated with cardiovascular disease mortality in men and women at apparently low risk. Health Psychology. 2010;29:412–420. doi: 10.1037/a0019432. doi: 10.1037/a0019432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor TD, Anstey KJ. A longitudinal investigation of perceived control and cognitive performance in young, midlife and older adults. Ageing, Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2008;15:744–763. doi: 10.1080/13825580802348570. doi: 10.1080/13825580802348570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]