Abstract

Morphogenesis of the hermaphrodite gonad of Caenorhabditis elegans is directed by the U-shaped migration of the gonadal leader cells, which are called distal tip cells (DTCs). The nuclei of migrating DTCs are always positioned at the leading edge of the cells, even as these cells turn dorsally to contact the hypodermis and intestine. When the DTCs turn dorsally, VAB-10B1/spectraplakin acts in nuclear translocation by regulating the polarized growth of microtubules. The function of spectraplakin in nuclear positioning may be evolutionarily conserved. Here we discuss the possible reason for leading-edge positioning of the DTC nucleus.

Keywords: spectraplakin, cytoskeleton, VAB-10B1, nuclear migration, cell migration

DTCs Change Their Morphology During Dorsal Migration

The gonadal distal tip cells (DTCs) of C. elegans migrate in a U-shaped pattern during larval development and lead the morphogenesis of the U-shaped gonad arms. The DTC migration offers a simple model for the tip-cell-dependent morphogenesis of epithelial tubes. Morphogenesis by extension and branching of epithelial tubes, which is called “branching morphogenesis,” is one of the major strategies found in organ formation. Recently, the migration of epithelial tubes was shown to be often controlled by a cell or a group of cells at the tip of the growing tubes.1 Although the C. elegans gonad arms do not branch, the DTCs migrate along a complex trajectory comprising three linear phases punctuated by two orthogonal turns. Each DTC forms a close-fitting cap over the 6–10 germ cells and had been thought to maintain this morphology during the course of its migration.2 Unexpectedly, however, DTCs were found to change their shape dramatically at the first turn.3 DTCs that expressed GFP-moesin, which labels cortical actin filaments, were analyzed by confocal microscopy and shown to extend a single large lamellipodium dorsally when they make the first turn (Fig. 1). The DTCs then migrate dorsally by invading the contact site of the intestine and the lateral epidermis.

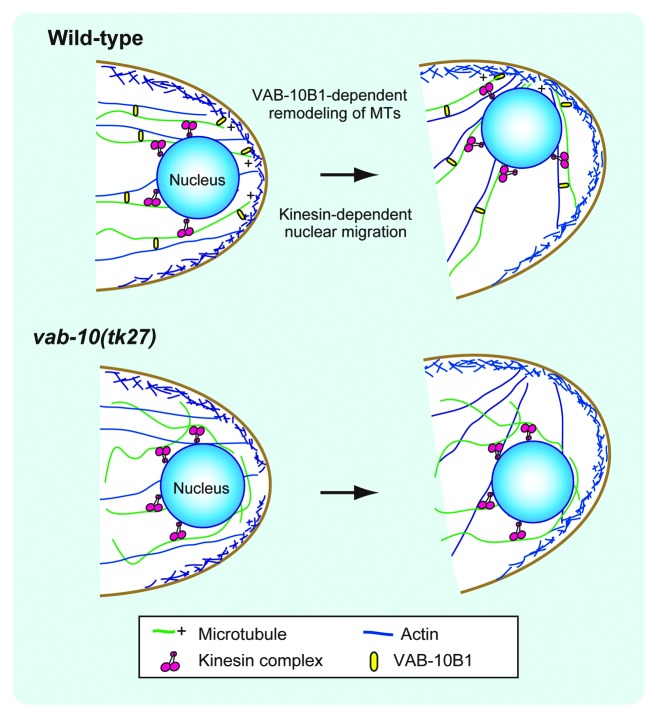

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of DTCs and their nuclear migration during gonadogenesis. DTCs migrating on the ventral muscles (A), initiating dorsal lamellipodial extension into the contact site between the hypodermis and intestine (B), moving dorsally between the hypodermis and intestine (C), and reaching the dorsal muscle (D) are shown. Note that the DTC nucleus is always present at the leading edge of the cell.

VAB-10B1/Spectraplakin Acts in Nuclear Positioning

It is interesting to note that the DTCs consistently position their nuclei at the leading edge throughout their migration. When the DTCs turn dorsally, their nuclei are relocated to the dorsal side of the DTCs (Fig. 1). The DTCs extend lamellipodia at the onset of this turn and thus place their nuclei near the leading edge. This nuclear translocation requires the action of VAB-10B1, one of the spectraplakin isoforms in C. elegans.3 Spectraplakins are large cytoplasmic proteins that regulate the cytoskeleton.4-6 Nuclear translocation in DTCs is suppressed in mutants lacking VAB-10B1. Although the network of F-actin is mostly normal in these animals, the microtubule (MT) network is severely disrupted.3 VAB-10B1 has an N-terminal actin-binding domain (ABD), which is followed by a plakin domain, spectrin repeats, and an MT-binding domain (MTBD). Spectraplakins are known as the linker protein that bridges actin and MT filaments, because mini-genes containing only the ABD and MTBD domains can rescue the defects in the MT cytoskeleton in cultured cells,7,8 and in axonal growth in Drosophila9 that occur in the absence of functional endogenous spectraplakins. DTC-specific expression of the vab-10B1 mini-gene also rescued defective nuclear translocation in vab-10B1 mutant larvae, suggesting a similar linker activity for VAB-10B1.3

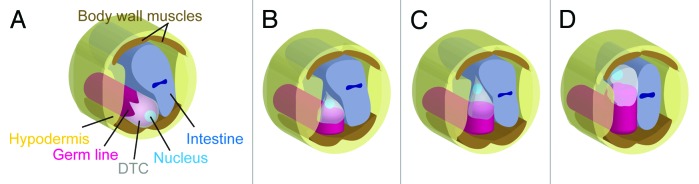

F-actin and MTs are often aligned along the migratory axis of DTCs, and MTs grow toward the nucleus in the leading edge of the migrating DTCs. This polarized outgrowth of MTs is compromised in vab-10B1 mutants. Disruption of kinesin, a plus-end motor of MTs, also results in nuclear translocation defects in DTCs (Kim and Nishiwaki, unpublished data). These results suggest that, via its linker activity, VAB-10B1 functions in polarized outgrowth of MTs along the actin filaments, which are arrayed in parallel to the migratory axis of DTCs, and that the DTC nuclei are carried over the MT fibers toward the migratory leading edge in a kinesin-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Spectraplakin is reported to regulate MT outgrowth along actin bundles in mammalian cultured cells.7

Figure 2. Model for nuclear translocation in DTCs. VAB-10B1 mediates linking between MTs and F-actin, which facilitates the outgrowth of MTs to direct the plus ends toward the migratory leading edge of the cell. As DTCs turn dorsally, it is likely that F-actin is first redirected dorsally. Then the MTs are remodeled to grow dorsally along the F-actin network. The nuclei of the DTCs are translocated to the leading edge of the cells over the MT fibers in a kinesin-dependent manner. In vab-10B1 mutants, as the polarized outgrowth of MTs is disrupted, the kinesin-dependent nuclear migration fails.

Is the Function of Spectraplakin in Nuclear Positioning Evolutionarily Conserved?

The functions of spectraplakins in F-actin and MT regulation (localization, alignment, polarity and outgrowth) have been studied mainly in cell migration and axon extension.7-9 Kim et al. (2011) for the first time showed that spectraplakin is actively engaged in nuclear translocation via its function in MT regulation. The function of spectraplakin in nuclear positioning was, however, noticed early on in naturally occurring mutant mice. In mice with the neurodegenerative disorder dystonia musculorum, the causative gene was found to encode the spectraplakin Bpag1.10,11 Among the characteristic pathological features detected in dystonia mice is the eccentricity of neuronal nuclei.12-14 The zebrafish mutant magellan, which affects the spectraplakin microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1 (MACF1), is also defective in nuclear positioning in oocytes.15 In the zebrafish mutant, although abnormal MT localization is found in the oocytes, it is not known if this MT mislocalization affects nuclear positioning. As there are many studies that have shown an involvement of MT activity in the migration or positioning of cellular nuclei in various developmental contexts,16,17 it is possible that the role of spectraplakin in directional MT alignment to achieve appropriate positioning of nuclei in cells is conserved evolutionarily.

Why is the Nucleus of the DTC Placed at the Leading Edge of These Migrating Cells?

Nuclear migration occurs during the differentiation and morphogenesis of diverse cell types. For example, the migration of the nucleus into the bud neck in S. cerevisiae is important for normal distribution of chromosomes between mother and daughter cells.18 The interkinetic nuclear migration seen in vertebrate neuroepithelia is correlated with the cell cycle and is thought to regulate the fates of daughter cells.19 In Drosophila early embryos, the migration of nuclei to the cell cortex is essential for forming the syncytial blastoderm.20

In mammalian cultured cells, nuclei are actively moved away from the migratory leading edge.21 This nuclear replacement is important for positioning the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) and Golgi apparatus in front of the nucleus, which may facilitate the delivering of membrane precursors and actin regulators to the leading edge.22,23 In contrast, the nuclei of migrating DTCs are positioned at the leading edge. It is unclear why the nuclei of DTCs are actively translocated to this region of the migrating cell. The absence of UNC-83/KASH, a nuclear membrane protein required for DTC nuclear translocation, also affects DTC cell migration, albeit weakly. These mutant DTCs exhibit weak pathfinding defects during their migration (Kim and Nishiwaki, unpublished data; ref. 24). Thus, it is possible that nuclear positioning at the leading edge may play some role in guiding DTC migration. Because the guidance of DTCs during their dorsal migration depends on UNC-6/netrin signaling,25,26 it might be possible that the UNC-6 receptors UNC-5 and/or UNC-40 may be expressed in the membrane region at the leading edge of DTCs. If the nucleus was positioned close to the leading edge under these circumstances, this would allow the efficient transduction of the UNC-6 signal to the nucleus. The UNC-6 signal could then activate the expression of genes that are required for polarized extension of the lamellipodium of the DTC. Further analysis of cell and nuclear migration of DTCs is required to determine a detailed understanding of nuclear positioning at the leading edge.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas to K.N.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/worm/article/19500

References

- 1.Lu P, Werb Z. Patterning mechanisms of branched organs. Science. 2008;322:1506–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1162783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lints R, Hall DH. Reproductive System. In Altun ZF and Hall DH, ed. C.elegans Atlas. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2008;243-258. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HS, Murakami R, Quintin S, Mori M, Ohkura K, Tamai KK, et al. VAB-10 spectraplakin acts in cell and nuclear migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2011;138:4013–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.059568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karakesisoglou I, Yang Y, Fuchs E. An epidermal plakin that integrates actin and microtubule networks at cellular junctions. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:195–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung CL, Sun D, Zheng M, Knowles DR, Liem RK. Microtubule actin cross-linking factor (MACF): a hybrid of dystonin and dystrophin that can interact with the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1275–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun D, Leung CL, Liem RK. Characterization of the microtubule binding domain of microtubule actin crosslinking factor (MACF): identification of a novel group of microtubule associated proteins. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:161–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Kodama A, Fuchs E. ACF7 regulates cytoskeletal-focal adhesion dynamics and migration and has ATPase activity. Cell. 2008;135:137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kodama A, Karakesisoglou I, Wong E, Vaezi A, Fuchs E. ACF7: an essential integrator of microtubule dynamics. Cell. 2003;115:343–54. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Kolodziej PA. Short Stop provides an essential link between F-actin and microtubules during axon extension. Development. 2002;129:1195–204. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown A, Bernier G, Mathieu M, Rossant J, Kothary R. The mouse dystonia musculorum gene is a neural isoform of bullous pemphigoid antigen 1. Nat Genet. 1995;10:301–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo L, Degenstein L, Dowling J, Yu QC, Wollmann R, Perman B, et al. Gene targeting of BPAG1: abnormalities in mechanical strength and cell migration in stratified epithelia and neurologic degeneration. Cell. 1995;81:233–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90333-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duchen LW, Strich SJ, Falconer DS. Clinical and pathological studies of an hereditary neuropathy in mice (dystonia musulorum) Brain. 1964;87:367–78. doi: 10.1093/brain/87.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotelo C, Guenet JL. Pathologic changes in the CNS of dystonia musculorum mutant mouse: an animal model for human spinocerebellar ataxia. Neuroscience. 1988;27:403–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanker JS, Peach R. Histochemical and ultrastructural studies of primary sensory neurons in mice with dystonia musculorum: Acetylcholinesterase and lysosomal hydrolases. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1976 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1976.tb00487.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta T, Marlow FL, Ferriola D, Mackiewicz K, Dapprich J, Monos D, et al. Microtubule actin crosslinking factor 1 regulates the Balbiani body and animal-vegetal polarity of the zebrafish oocyte. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke B, Roux KJ. Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location. Dev Cell. 2009;17:587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starr DA. A nuclear-envelope bridge positions nuclei and moves chromosomes. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:577–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adames NR, Cooper JA. Microtubule interactions with the cell cortex causing nuclear movements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:863–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baye LM, Link BA. Nuclear migration during retinal development. Brain Res. 2008;1192:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royou A, Sullivan W, Karess R. Cortical recruitment of nonmuscle myosin II in early syncytial Drosophila embryos: its role in nuclear axial expansion and its regulation by Cdc2 activity. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:127–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes ER, Jani S, Gundersen GG. Nuclear movement regulated by Cdc42, MRCK, myosin, and actin flow establishes MTOC polarization in migrating cells. Cell. 2005;121:451–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergmann JE, Kupfer A, Singer SJ. Membrane insertion at the leading edge of motile fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:1367–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prigozhina NL, Waterman-Storer CM. Protein kinase D-mediated anterograde membrane trafficking is required for fibroblast motility. Curr Biol. 2004;14:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malone CJ, Fixsen WD, Horvitz HR, Han M. UNC-84 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for nuclear migration and anchoring during C. elegans development. Development. 1999;126:3171–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Culotti JG, Merz DC. DCC and netrins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:609–13. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedgecock EM, Norris CR. Netrins evoke mixed reactions in motile cells. Trends Genet. 1997;13:251–3. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]