Abstract

The signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT3 is a transcription factor which plays a key role in normal cell growth and is constitutively activated in about 70% of solid and hematological cancers. Activated STAT3 is phosphorylated on tyrosine and forms a dimer through phosphotyrosine/src homology 2 (SH2) domain interaction. The dimer enters the nucleus via interaction with importins and binds target genes. Inhibition of STAT3 results in the death of tumor cells, this indicates that it is a valuable target for anticancer strategies; a view that is corroborated by recent findings of activating mutations within the gene. Yet, there is still only a small number of STAT3 direct inhibitors; in addition, the high similarity of STAT3 with STAT1, another STAT family member mostly oriented toward apoptosis, cell death and defense against pathogens, requires that STAT3-inhibitors have no effect on STAT1. Specific STAT3 direct inhibitors consist of SH2 ligands, including G quartet oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) and small molecules, they induce cell death in tumor cells in which STAT3 is activated. STAT3 can also be inhibited by decoy ODNs (dODN), which bind STAT3 and induce cell death. A specific STAT3 dODN which does not interfere with STAT1-mediated interferon-induced cell death has been designed pointing to the STAT3 DBD as a target for specific inhibition. Comprehensive analysis of this region is in progress in the laboratory to design DBD-targeting STAT3 inhibitors with STAT3/STAT1 discriminating ability.

Keywords: STAT3, STAT1, decoy oligodeoxynucleotides, G quartet oligodeoxynucleotides, SH2 domain, anti-tumor, anti-cancer compounds

Central Role of STAT3 in Tumors

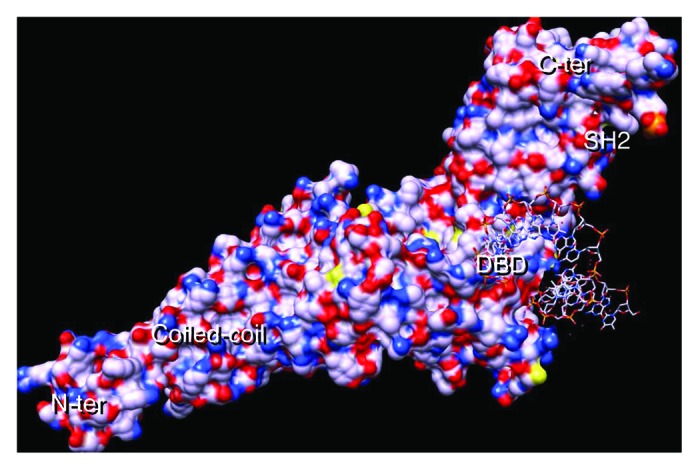

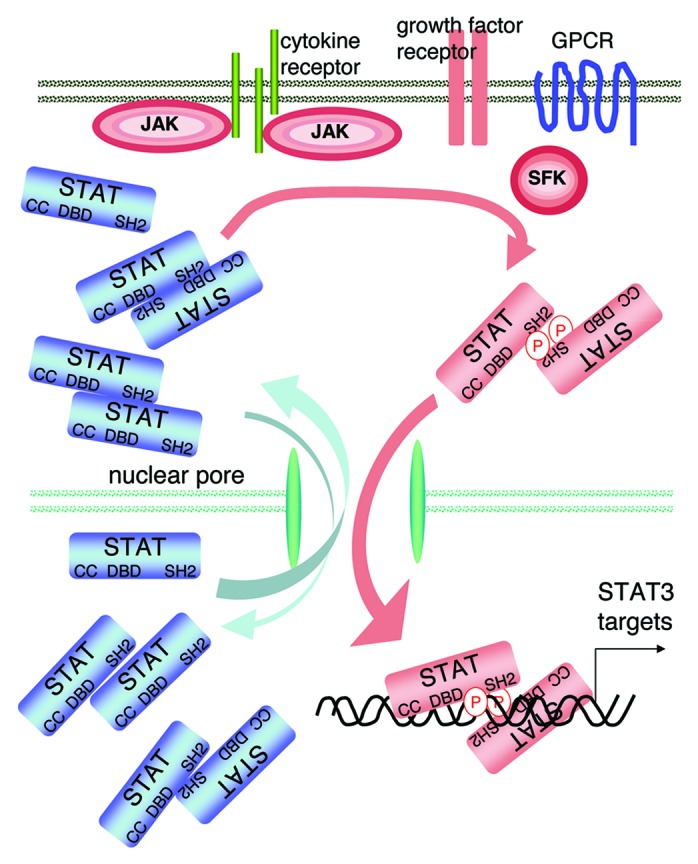

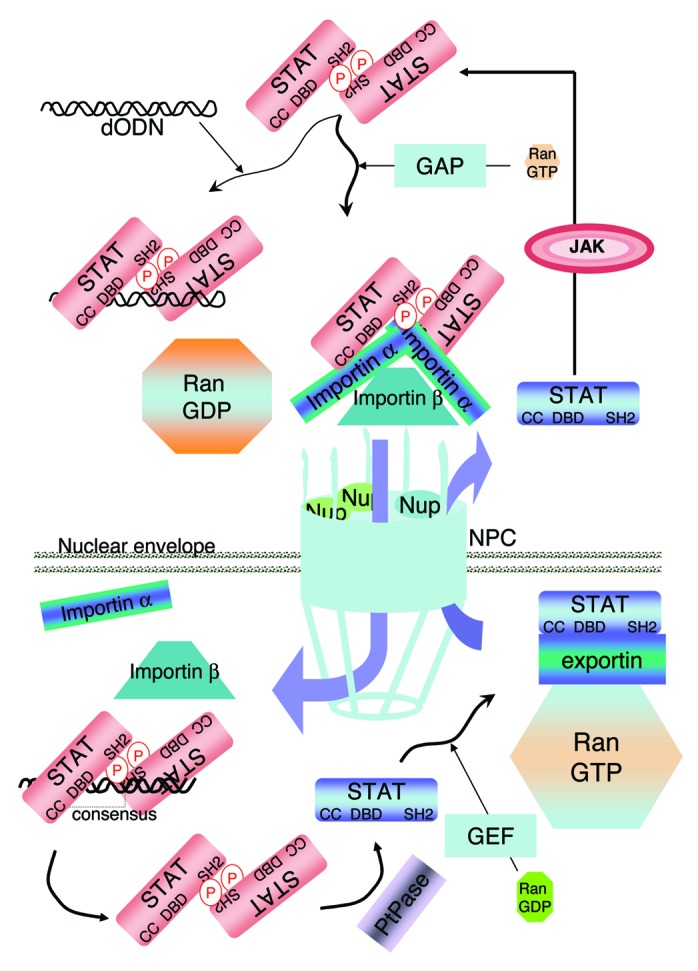

STAT3 belongs to a family of transcription factors (TFs) comprising STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B and STAT6.1 Like STAT5, STAT3 was found to play an important role in cell growth,2 and its activation has been described in nearly 70% of solid and hematological tumors,3,4 giving good reason for a search for specific direct inhibitors,5,6 of which there are unfortunately only a few, and none in the clinic to this day. STAT3 comprises several distinct functional domains including: an N-terminal domain containing an oligomerization and a coiled-coil domain, a DNA binding domain (DBD), a linker domain, a Src homology 2 (SH2) domain involved in the interaction of two monomers via phosphotyrosine 705 resulting in dimerization and a C-terminal transactivation domain (see Fig. 1). STAT3 activation occurs following cytokine- or growth factor-receptor activation; it involves phosphorylation within the cytoplasm, dimerization and nuclear transfer7 (Fig. 2). Nuclear transfer of STAT3 requires nuclear localization signals (NLS) which are in the coiled-coil domain (comprising arginines 214 and 2158) and in the dimer-dependent DBD (comprising arginines 414 and 4179). The NLSs interact with importin αs, yet which of the five importin αs (α1, α3, α4, α5 or α7) actually carries STAT3 is still debated,9,10 the complex interacts with importin β and is carried through the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (Fig. 3). While arginines 214 and 215 appear to be the major importin-binding site, arginines 414 and 417 are thought to be required for STAT3 to adopt the proper conformation for importin binding.9 Several studies have shown that STAT3 cycling is probably somewhat more complicated. Unphosphorylated forms of STAT3 can enter the nucleus and stimulate transcription of a subset of gene targets, apparently via interaction with the TF NFκB.11 However, whether unphosphorylated STAT3 interacts on its own with importins for nuclear entry is not entirely clear: tyrosine 705-mutated STAT3 can shuttle to the nucleus12 and phosphotyrosine 705/SH2-independent STAT3 dimers were shown to enter the nucleus (but more slowly than phosphorylated STAT3 dimers)13 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, in the case of STAT1, unphosphorylated monomers enter the nucleus through direct interaction with the NPC proteins nucleoporins, not with importins14 and unphosphorylated STAT1 dimers bind DNA with a 200-fold lower affinity than phosphorylated STAT1 dimers;15 in fact, single-molecule imaging showed that interferon (IFN)-γ-activated STAT1 has a reduced mobility and resides longer in the nucleus.16 In any case, the nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of STAT3 is a major step of the activation process leading to increased transcriptional activity, suggesting that nuclear transfer of STAT3 per se can be a target for inhibition.

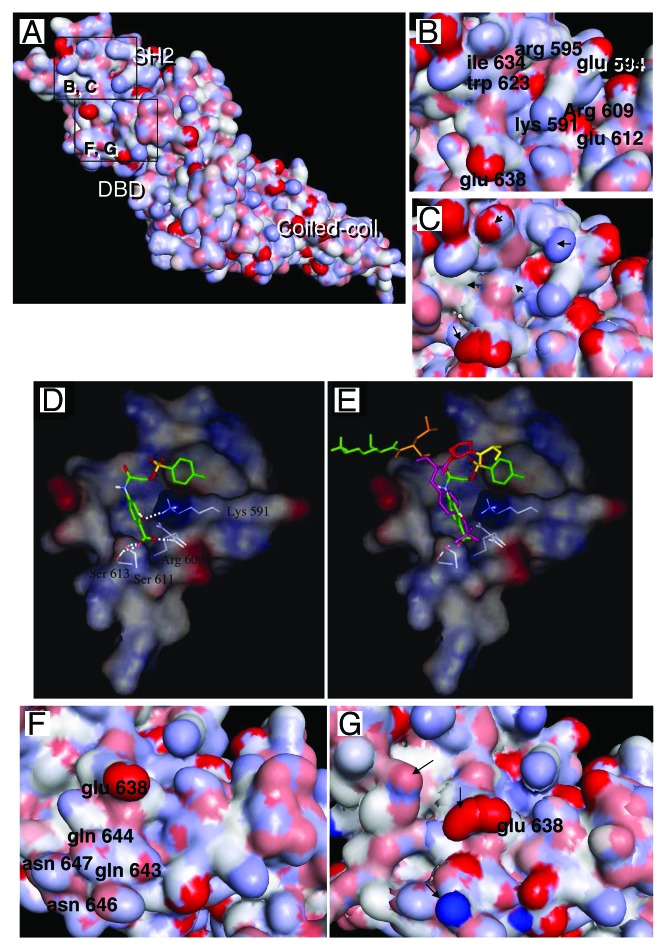

Figure 1. STAT3 with DNA-consensus sequence. STAT3 monomer showing the N-terminal coiled-coil domain, the DBD (half site), the SH2 domain and the C-terminal domain. Basic residues are blue and acid ones are red. The STAT3 crystal coordinates were downloaded from the protein data bank (PDB, file: 1BG1) and analyzed using the chimera program.73 Note that the model shown comprises residues 136 to 716;74 hence, the protein’s N-terminal and C-terminal domains (comprising the transactivation domain) are missing; the coordinates corresponding to the cDNA strand were missing in the model and had to be reconstructed.65

Figure 2. STAT3 activation. The transcription factor STAT3 is present in a latent inactive non-phosphorylated form in the cytoplasm. Activated cytokine receptors activate the kinases JAK, which phosphorylate tyrosines located in the cytoplasmic portion of the cytokine receptors creating STAT-binding motifs. Once bound to these motifs, STAT3 becomes in turn phosphorylated by the JAKs. The phospho STAT3 dimers (colored in pink) enter the nuclei and bind STAT3 target genes; note that the DNA-bound dimer is drawn differently to indicate the STAT3 conformational change suggested by molecular dynamics simulations.22 STAT3 can also be activated by tyrosine kinases of the Src family (SFK), the SFKs can themselves be activated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) or growth factor receptors, the growth factor receptors (including EGF-receptors and VEGF-receptors) can also phosphorylate STAT3. The DBD is created by the phosphotyrosine 705/SH2-mediated dimer. There are also monomers, and dimers with non-phosphorylated STAT3, which can shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus.

Figure 3. STAT3 nuclear entry. The tyrosine phosphorylated STAT3 dimer interacts with the importins through its two NLSs [one within the coiled-coil (mL) domain: arginines 214 and 215; one within the DBD: arginines 414 and 417]. This complex is carried through the nuclear pore complex (NPC) by the Ran GDP which is formed in the cytoplasm by hydrolysis of Ran-bound GTP by GTPase activating protein (GAP). The NPC comprises nucleoporins (Nup). The importins release the dimer once it enters the nucleus. The high level of Ran-GTP in the nucleus is the result of a high GTP-exchange factor (GEF) activity in this compartment. The STAT3 dimer interacts with the STAT3 DNA consensus motif and then is released; once released from DNA the dimer is dephosphorylated by a nuclear phosphatase (PtPase). The dephosphorylated STAT3 is exported to the cytoplasm in combination with exportins and Ran-GTP.

Constitutive activation of STAT3 in tumors can result from upstream activated signaling components, including increased cytokines (IL-6 and IL-10) production, activated receptor (cytokine receptors, VEGFR and EGFR) and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (including JAKs, Src and Abl). Recently, mutated hyperactive forms of STAT3 have been detected in tumors, interestingly most of the described mutations are located within STAT3’s SH217,18 (see ref. 19). Due to the involvement of tyrosine protein kinases in the STAT3 activating pathways, tyrosine kinase inhibitors indirectly inhibit STAT3 resulting in anti-tumor activity. But STAT3 can also be activated when suppressors of the STAT signaling pathway are inactivated such as the SOCS (suppressor of cytokine signaling), the PIAS (protein inhibitor of activated STATs) and protein tyrosine phosphatases;20 furthermore, in cells in which proliferation results from the inactivation of negative regulators of signaling, such as the inhibitor of the PI3Kinase pathway PTEN, or the inhibitor of the proapoptotic TF p53, MDM2, the inhibition of upstream signaling pathways may have little effect. Thus, when upstream STAT3 activators are not identified or do not have any known inhibitor, or when STAT3 is itself activated it becomes a relevant target for anti-tumor treatments. This reasoning, reinforced by STAT3’s previously noted “signaling bottleneck” situation,21 has been used by many authors searching for STAT3-specific direct inhibitors.

The Peculiar STAT3-STAT1 Connection

The high similarity between STAT3 and STAT1 is intriguing. Both TFs share a 50% amino-acid sequence homology22 and share similar activating stimuli (types I and II IFNs, cytokines and growth factors); yet, their functions differ: STAT1 is mostly involved in immunity, host defense against pathogens and cell death (see refs. 23 and 24), with the notable exception that in certain contexts STAT1 exerts proliferative potential,25 while STAT3 is mostly involved in cell growth and proliferation (see ref. 3). Their gene targets are mostly distinct: STAT3 stimulates the transcription of cell growth-associated genes, including cyclin-D1, survivin, Vegf, C-myc, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, vascular endothelial growth factor, IL-10, transforming growth factor β and Bcl23,26 and STAT1 stimulates the transcription of pro-inflammatory and anti-proliferative genes, including caspases, iNOS, Mdm2, p21waf/cip1 and p27kip127,28; but there is also an overlap of repertoires.23 In reality, STAT3 and STAT1 recognize very similar DNA consensus sequences, based on a TTCNNN(T,G)AA motif29 (see Table 1). In this motif, a 3N spacing (N representing any base) is most frequently present for STAT1 and STAT3, as shown by electrophoretic migration shift assay (EMSA).30 Natural binding sites share this consensus with minor variations such as a preference for T at position −5 for STAT1, but there is greater diversity outside this consensus31 (see Table 1), suggesting that target recognition in vivo requires additional co-factors. Thus, when attempting to inhibit STAT3 with the aim to kill tumor cell or block their growth, one must use substances that have no effect on STAT1, as has been pointed out32,33 and shown in tumor cell lines with siRNA-suppressed STAT1.34,35 Indeed, STAT1 is required for the antiproliferative effects of interferons α and γ,36 apoptosis is defective in STAT1-null cells37 and STAT1 is the major effector of IFN-γ, a cytokine with antitumor and cancer immunosurveillance functions.38,39

Table 1. Comparison and alignment of the STAT3 and STAT1 specific DNA recognition sites and of the dODNs used to inhibit STAT3.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-9 |

-8 |

-7 |

-6 |

-5 |

-4 |

-3 |

-2 |

-1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

STAT1 |

References |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

T |

A |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

G |

G |

A |

A |

A |

T |

C |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

75 |

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

G |

C |

T |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

C |

T |

A |

A |

A |

T |

G |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

76, 77 |

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T |

G |

A |

T |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

C |

G |

A |

A |

T |

G |

A |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

78 |

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

G |

G |

T |

T |

T |

C |

C |

G |

G |

G |

A |

A |

A |

G |

C |

A |

|

|

|

|

|

79 |

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

C |

T |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

G |

A |

A |

A |

C |

G |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

80 |

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

C |

A |

T |

T |

T |

C |

G |

G |

A |

G |

A |

A |

G |

A |

C |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

81 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

C |

A |

C |

T |

T |

C |

T |

G |

A |

T |

A |

A |

A |

G |

C |

A |

|

|

|

|

|

82 |

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

A |

G |

T |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

G |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

C |

T |

|

|

|

|

|

83 |

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T |

G |

T |

G |

A |

A |

T |

T |

A |

C |

C |

G |

G |

A |

A |

G |

T |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

84 |

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

T |

A |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

G |

T |

A |

A |

G |

T |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

85, 86 |

| 11 |

C |

A |

T |

G |

T |

T |

A |

T |

G |

C |

A |

T |

A |

T |

T |

C |

C |

T |

G |

T |

A |

A |

G |

T |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

87 |

| 12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

G |

C |

G |

T |

T |

C |

T |

T |

G |

G |

A |

A |

A |

T |

G |

C |

G |

C |

C |

|

|

88 |

|

STAT3 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

A |

T |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

G |

T |

A |

A |

A |

T |

C |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

57 |

| 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

C |

A |

G |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

G |

T |

C |

A |

A |

T |

C |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

89 |

| 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

G |

G |

C |

A |

G |

C |

A |

T |

|

|

|

|

|

90 |

| 16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

C |

A |

G |

T |

T |

C |

C |

A |

G |

G |

A |

A |

T |

C |

G |

G |

G |

|

|

|

|

91 |

| 17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

T |

G |

C |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

G |

A |

A |

C |

G |

T |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

| 18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

G |

G |

C |

T |

T |

G |

G |

C |

G |

G |

G |

A |

A |

A |

A |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

92 |

| 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

C |

T |

G |

G |

G |

A |

A |

T |

T |

C |

T |

A |

|

|

|

|

93 |

| 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

T |

C |

C |

T |

T |

C |

T |

G |

G |

G |

A |

A |

T |

T |

C |

T |

A |

G |

A |

T |

C |

86, 94 |

|

STAT3 dODNs |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

A |

T |

T |

T |

C |

C |

C |

G |

T |

A |

A |

A |

T |

C |

G |

|

|

|

|

|

57 |

| 22 | T | A | T | T | T | C | C | C | C | T | A | A | A | T | G | G | 65 | |||||||||||||||

The STAT1 and STAT3 consensus sequences are shown in bold.

STAT3 Direct Inhibitors

The recognition that activated STAT3 is widely present in tumors and that its inhibition is a valuable anti-cancer strategy led to a search for STAT3-targeting compounds. Among those the DNA-alkylating platinum complexes were found to induce the death of tumor cells with activated STAT3 and were thought to act directly on STAT3;40 other compounds target the SH2 of STAT3, including G quartet oligodeoxynucleotides and small molecules, some of which are highly specific for STAT3. STAT3 inhibitors also comprise the decoy oligodeoxynucleotides which target the DBD.

Small molecules targeting the SH2 domain and inhibiting STAT3 dimerization

The dimerization of STAT3 through reciprocal phosphotyrosine 705/SH2 interaction can be impaired by a phosphopeptide with the sequence PpYLKTK. This phosphopeptide inhibits STAT3 activity in tumor cell lines, induces cell death41 and has a high affinity and specificity for STAT3: in particular it had no effect on the SH2-containing tyrosine kinase p56lck, and little effect on STAT1 as determined by EMSA. Despite their efficacy and specificity, the inefficient cell penetration of phosphopeptides led to a search for smaller equivalents using computational docking studies exploring the phosphotyrosine 705/SH2 interaction area (see Fig. 3A and B). These studies yielded several small molecules with high affinity and high specificity for STAT3, including STA-21,42 Stattic,43 S31-20144 and recently BP-1-102, a compound with improved bioavailability and anti-cancer properties.45 The mechanism of action of these compounds is thought to be based on their interaction with STAT3 SH2 (Fig. 4A and B), an area where the other monomer’s phosphotyrosine 705 docks, thereby impairing the formation of the active dimer, as shown in44 (see Fig. 4D and E, borrowed from ref. 44; the phosphotyrosine peptide is represented together with the inhibitor S31-201, both form H-bonds with the same residues, including lysine 591, serine 611, serine 613 and arginine 609). Interestingly, STAT1-specific inhibitors have also been obtained using this peptidomimetic strategy.46 STAT3 SH2-targeting compounds are efficacious STAT3 inhibitors, they inhibit STAT3 DNA binding, reduce STAT3-dependent cell proliferation and expression of biological targets. Yet, experimental demonstration of their interaction with STAT3 is missing, the actual data are based on computational studies, not on actual interaction measurements, as noted earlier.47 This implies that a compound claimed to interact with SH2 might actually interfere with the binding of STAT3 to the receptor’s phosphotyrosine site leading to biological effects similar to those of JAK-inhibitors. The compound might also interact with the DBD with just the same effect in the cell (reduced DNA binding, cell death). Besides, compounds usually undergo modifications in a biological environment (cells or body fluids), these modifications can occur before the compounds reach their target. For instance, Stattic’s inhibitory activity of STAT3 increases with time and is temperature- and dithiothreitol-sensitive, this suggests that it interacts with a cysteine, such as cysteine 687 which is next to the phosphopeptide motif of STAT3 and faces the phosphopeptide-binding area of SH2.47 While this point does not invalidate Stattic’s specificity for STAT3, it suggests possible limitations for its in vivo utilization. Despite considerable progress and clear anti-cancer efficacy, this family of compounds has not reached the clinic.

Figure 4. A detailed view of STAT3 SH2 and DBD regions. (A) STAT3 surface obtained as in Figure 1. The areas in squares are the SH2 region where small molecules interact (B and C) and the SH2/DBD region where G quartets interact (D and E). (B) Close up view of the region of the SH2 of STAT3 that interacts with the small molecule inhibitors: the key aminoacids involved in interaction are labeled; the inhibitors interact particularly in the groove located between arginine 595 and lysine 591. (C) The same area as in (B) is shown but STAT3 and STAT1 are superimposed; this shows the overall great similarity between these two regions, yet some differences are present, accounting for the capacity of the inhibitors to discriminate between STAT3 and STAT1 (arrows); STAT1 crystal coordinates66 used in (C) were from PDB file 1BF5. (D) Modeled interaction of inhibitor S31-201 with STAT3 SH2 domain, note the important role of lysine 591, serine 611 and arginine 609 in the interaction. (E) Same as (D), with added phosphotyrosine-peptide, showing its overlap with the STAT3 SH2/small molecule inhibitors binding area. (F) Detailed view of the region of STAT3 interacting with G quartets, this region includes the phosphotyrosine 705-interacting region of SH2 and a neighboring region including part of the DBD, including glutamic acid 638, glutamine 644, aspartic acid 647, glutamine 643 and asparagine 646. (G) Same region as in F is shown with the superimposition of STAT1, the major differences are indicated by arrows. [Panels (D and E) are reprinted from ref. 44 with permission; © 2007 National Academy of Sciences USA.]

G quartet oligodeoxynucleotides

G quartets are G-rich oligodeoxynucleotides that form potassium-dependent four-stranded intramolecular G-quartet structures.48 They inhibit STAT3 at micromolar concentrations and induce the death of several tumor cell lines, including head and neck cancer lines, they also arrest the development of breast tumor, prostate tumor or non-small cell lung cancer xenografts in nude mice.48,49 These reagents are interesting in that their specificity for STAT3, demonstrated by EMSA showing high affinity binding to STAT3 and much lower affinity for STAT1,50 is somewhat unexpected. A computational study of the interaction of the G quartet with STAT3 and STAT1 showed the following SH2 domain amino-acids to be involved in the binding: glutamic acid 638, glutamine 644, asparagine 647, glutamine 643 and asparagine 64651 (Fig. 4F). Using a 3D analysis program (Accelrys) we compared STAT3 and STAT1 surfaces in the area where the G quartet interacts and found that the surfaces differ significantly (Fig. 4F and G). However, the use of G quartets is problematic due to their large size and potassium dependence, which limit cellular delivery.52,53

Decoy oligodeoxynucleotides targeting the DNA binding domain

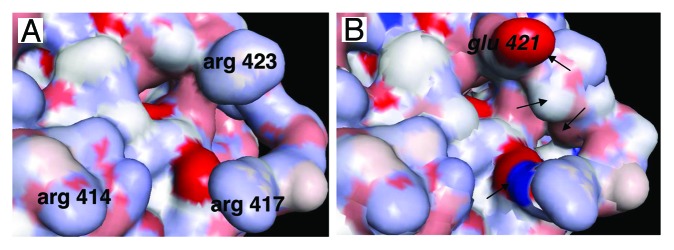

Decoy oligodeoxynucleotides (dODNs) are short stretches of double stranded DNA containing a TF’s consensus binding sequence. Once in the cells, dODNs inhibit the corresponding TF as shown for NFκB in animal models (cardiovascular disease54 and ischemia-reperfusion injury55) and in cancer cells.56 This property has been used for STAT3: in cells in which STAT3 is constitutively activated, STAT3 dODNs (Table 1) induce cell death.35,57,58 While some studies suggested that dODNs must enter nuclei to exert their inhibitory action,59,60 our studies of the subcellular location of STAT3 in dODN-treated cells have shown that the dODNs prevent nuclear translocation of STAT3.35,58 The dODNs are thought to interact with STAT3′s DBD within the cytoplasm and to prevent interaction with importins35 which carry the STAT3 dimer within the nucleus.7 Inhibition of importin binding by the dODN is thought to result from the masking of the DBD-located NLS (arginines 414 and 417) (see Figs. 1 and 5A) indirectly confirming its involvement in nuclear entry.9 In fact, competition between DNA binding and importin binding was observed in vitro with STAT161 and within cells with STAT3.35 Thus, despite the uncertainty regarding the two STAT3 NLSs’ relative requirement for nuclear transfer, it seems that the DBD-located NLS plays an important role for nuclear translocation since its masking is sufficient to impair it, confirming that it may be a good target for inhibition, as suggested by others.7,53,62

Figure 5. Detailed view of the area of STAT3 interacting with DNA and importins. (A) Detail of the area of STAT3 interacting with the DNA consensus sequence. Arginines 414 and 417 play a key role in the interaction of STAT3 with importins and nuclear translocation, arginine 423 is involved in the interaction of DNA with STAT3.65 (B) The same area as in (A) is shown, the corresponding area of STAT1 has been superimposed, showing the high level of homology between STAT3 and STAT1, except for glutamic acid 421 (in italic) of STAT1 whose interaction with DNA is very different from that of arginine 423 of STAT3 (see ref. 65), and other differences indicated by arrows.

As discussed above, the opposed cellular functions of STAT1 and STAT3, in spite of their similarity, is puzzling. STAT1 and STAT3 can form heterodimers, whose function is not elucidated to this day, they recognize very similar DNA motifs (table), and they have targets in common and regulate one another. Indeed, in STAT3-deficient cells, STAT3-activators such as IL-6 trigger an IFN-γ-like response through STAT1 activation63,64; and in STAT1-deficient cells, IFN-γ and IFN-α trigger STAT3-dependent proliferative responses.23 Thus the STAT1/STAT3 cross-regulation suggests that STAT3 inhibitors may work best in STAT1-expressing cells.28,35 It is therefore essential to inhibit STAT3 without inhibiting STAT1 to keep cell death processes operational. In this regard, it should be noted that STAT3-dODNs inhibit STAT357,58 but also inhibit activated STAT1, thereby abolishing IFN-γ-induced cell death35,58 and reducing the dODNs anti-STAT3 efficacy. Computer analysis of the dODN’s interaction with STAT1 and STAT3 DBDs showed that within the highly similar DNA sequences, there were subtle differences including a T at positions −7 and −5, a dC at position 0, a dA at position +5 (see Table 1, dODN #22),65 which had been previously noted by computer analysis66 and DNA-binding studies.30,31,67,68 This allowed designing a dODN that could inhibit STAT3 without inhibiting STAT1, demonstrating that at this level specific interaction can be achieved.65 Therapeutic use of the dODNs not only requires specific target recognition, but also stability in biological fluids. Modifications, including phosphothioate end modification and hairpin structures35,58,69,70 considerably increased intracellular stability and efficacy. A recent improvement consisting of a cyclic STAT3 dODNs comprising a hairpin at both ends was designed and found to reduce xenograft tumors following intravenous administration.71 Furthermore, a STAT3 dODN has been found to have few side effects when administered to primates,72 suggesting interesting therapeutic perspectives.

Another possibility is to design smaller molecules mimicking the dODN’s interaction with STAT3, similarly to what was achieved with the SH2 domain. The STAT3 area that interacts with the DNA target and the dODN (Fig. 5A) is of particular interest because it also interacts with importins. This area comprises the DBD-located NLS including arginines 414 and 417 that are located closely to arginine 423, involved in interaction with the dODN; these three arginines surround an opening in the surface in which small molecules could interact (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, superimposition of STAT3 and STAT1 showed that in spite of their striking overall similarity, these areas comprise in the same location glutamic acid 421 in STAT1 and arginine 423 in STAT365 (Fig. 5B), a difference that might be exploited for the design of a STAT3 small molecule inhibitor with STAT3/STAT1 discriminating capacity; studies are underway in the laboratory to try and design such a reagent.

Conclusion

Because STAT3 is constitutively activated in nearly 70% of tumors, it provides a valuable target for anti-cancer therapy. The recent findings that tumors harbor activating mutations of STAT3 underlines the need for additional STAT3 inhibitors, and inhibitors that target other regions of STAT3 than its SH2, especially as most identified mutations are within this region. In addition, studies on cancer cell lines indicate that even when STAT3 direct targeting is insufficient to induce cell death; it can diminish the resistance to other anti-cancer compounds such as doxorubicin or EGFR inhibitors. Finally, STAT3 direct inhibitors are also probably less toxic than many others because inhibition of STAT3 in mature cells has minimal effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant (BQR) from University Paris 13.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- IFNs

interferons

- GAS

gamma-interferon-activated sequence

- EMSA

electrophoretic migration shift assay

- pY

phosphotyrosine

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/jak-stat/article/22882

References

- 1.Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20059–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank DA. STAT signaling in the pathogenesis and treatment of cancer. Mol Med. 1999;5:432–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank DA. STAT3 as a central mediator of neoplastic cellular transformation. Cancer Lett. 2007;251:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-Natan M, Nelson EA, Xiang M, Frank DA. STAT signaling in the pathogenesis and treatment of myeloid malignancies. JAK-STAT. 2012;1:55–64. doi: 10.4161/jkst.20006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue P, Turkson J. Targeting STAT3 in cancer: how successful are we? Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:45–56. doi: 10.1517/13543780802565791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mankan AK, Greten FR. Inhibiting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3: rationality and rationale design of inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:1263–75. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.601739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich NC, Liu L. Tracking STAT nuclear traffic. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:602–12. doi: 10.1038/nri1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, Zhang T, Novotny-Diermayr V, Tan AL, Cao X. A novel sequence in the coiled-coil domain of Stat3 essential for its nuclear translocation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29252–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma J, Cao X. Regulation of Stat3 nuclear import by importin alpha5 and importin alpha7 via two different functional sequence elements. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, McBride KM, Reich NC. STAT3 nuclear import is independent of tyrosine phosphorylation and mediated by importin-alpha3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8150–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501643102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1396–408. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pranada AL, Metz S, Herrmann A, Heinrich PC, Müller-Newen G. Real time analysis of STAT3 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15114–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann A, Vogt M, Mönnigmann M, Clahsen T, Sommer U, Haan S, et al. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of persistently activated STAT3. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3249–61. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marg A, Shan Y, Meyer T, Meissner T, Brandenburg M, Vinkemeier U. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling by nucleoporins Nup153 and Nup214 and CRM1-dependent nuclear export control the subcellular distribution of latent Stat1. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:823–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenta N, Strauss H, Meyer S, Vinkemeier U. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the partitioning of STAT1 between different dimer conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802130105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speil J, Baumgart E, Siebrasse JP, Veith R, Vinkemeier U, Kubitscheck U. Activated STAT1 transcription factors conduct distinct saltatory movements in the cell nucleus. Biophys J. 2011;101:2592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilati C, Amessou M, Bihl MP, Balabaud C, Nhieu JT, Paradis V, et al. Somatic mutations activating STAT3 in human inflammatory hepatocellular adenomas. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1359–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koskela HL, Eldfors S, Ellonen P, van Adrichem AJ, Kuusanmäki H, Andersson EI, et al. Somatic STAT3 mutations in large granular lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1905–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groner B. Determinants of the extent and duration of STAT3 signaling. JAK-STAT. 2012;1:211–5. doi: 10.4161/jkst.21469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darnell JE., Jr. Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:740–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J, Buettner R, Yuan YC, Yip R, Horne D, Jove R, et al. Molecular dynamics simulations of the conformational changes in signal transducers and activators of transcription, Stat1 and Stat3. J Mol Graph Model. 2009;28:347–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regis G, Pensa S, Boselli D, Novelli F, Poli V. Ups and downs: the STAT1:STAT3 seesaw of Interferon and gp130 receptor signalling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:351–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Najjar I, Fagard R. STAT1 and pathogens, not a friendly relationship. Biochimie. 2010;92:425–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovacic B, Stoiber D, Moriggl R, Weisz E, Ott RG, Kreibich R, et al. STAT1 acts as a tumor promoter for leukemia development. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarnicki A, Putoczki T, Ernst M. Stat3: linking inflammation to epithelial cancer - more than a “gut” feeling? Cell Div. 2010;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chin YE, Kitagawa M, Kuida K, Flavell RA, Fu XY. Activation of the STAT signaling pathway can cause expression of caspase 1 and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5328–37. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avalle L, Pensa S, Regis G, Novelli F, Poli V. STAT1 and STAT3 in tumorigenesis a matter of balance. JAK-STAT. 2012;1:65–72. doi: 10.4161/jkst.20045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darnell JE, Jr., Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–21. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seidel HM, Milocco LH, Lamb P, Darnell JE, Jr., Stein RB, Rosen J. Spacing of palindromic half sites as a determinant of selective STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) DNA binding and transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3041–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehret GB, Reichenbach P, Schindler U, Horvath CM, Fritz S, Nabholz M, et al. DNA binding specificity of different STAT proteins. Comparison of in vitro specificity with natural target sites. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6675–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schindler C. STATs as activators of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:97–8. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(98)01233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CK, Smith E, Gimeno R, Gertner R, Levy DE. STAT1 affects lymphocyte survival and proliferation partially independent of its role downstream of IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2000;164:1286–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shim SH, Sung MW, Park SW, Heo DS. Absence of STAT1 disturbs the anticancer effect induced by STAT3 inhibition in head and neck carcinoma cell lines. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:805–10. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souissi I, Najjar I, Ah-Koon L, Schischmanoff PO, Lesage D, Le Coquil S, et al. A STAT3-decoy oligonucleotide induces cell death in a human colorectal carcinoma cell line by blocking nuclear transfer of STAT3 and STAT3-bound NF-κB. BMC Cell Biol. 2011;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bromberg JF, Horvath CM, Wen Z, Schreiber RD, Darnell JE., Jr. Transcriptionally active Stat1 is required for the antiproliferative effects of both interferon alpha and interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar A, Commane M, Flickinger TW, Horvath CM, Stark GR. Defective TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in STAT1-null cells due to low constitutive levels of caspases. Science. 1997;278:1630–2. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shankaran V, Ikeda H, Bruce AT, White JM, Swanson PE, Old LJ, et al. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 2001;410:1107–11. doi: 10.1038/35074122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–48. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turkson J, Zhang S, Palmer J, Kay H, Stanko J, Mora LB, et al. Inhibition of constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation by novel platinum complexes with potent antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1533–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turkson J, Ryan D, Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Haura E, et al. Phosphotyrosyl peptides block Stat3-mediated DNA binding activity, gene regulation, and cell transformation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45443–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song H, Wang R, Wang S, Lin J. A low-molecular-weight compound discovered through virtual database screening inhibits Stat3 function in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4700–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409894102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schust J, Sperl B, Hollis A, Mayer TU, Berg T. Stattic: a small-molecule inhibitor of STAT3 activation and dimerization. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1235–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiquee K, Zhang S, Guida WC, Blaskovich MA, Greedy B, Lawrence HR, et al. Selective chemical probe inhibitor of Stat3, identified through structure-based virtual screening, induces antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609757104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, Yue P, Page BD, Li T, Zhao W, Namanja AT, et al. Orally bioavailable small-molecule inhibitor of transcription factor Stat3 regresses human breast and lung cancer xenografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9623–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121606109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunning PT, Katt WP, Glenn M, Siddiquee K, Kim JS, Jove R, et al. Isoform selective inhibition of STAT1 or STAT3 homo-dimerization via peptidomimetic probes: structural recognition of STAT SH2 domains. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1875–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMurray JS. A new small-molecule Stat3 inhibitor. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1123–4. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jing N, Li Y, Xiong W, Sha W, Jing L, Tweardy DJ. G-quartet oligonucleotides: a new class of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 inhibitors that suppresses growth of prostate and breast tumors through induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6603–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weerasinghe P, Garcia GE, Zhu Q, Yuan P, Feng L, Mao L, et al. Inhibition of Stat3 activation and tumor growth suppression of non-small cell lung cancer by G-quartet oligonucleotides. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jing N, Zhu Q, Yuan P, Li Y, Mao L, Tweardy DJ. Targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 with G-quartet oligonucleotides: a potential novel therapy for head and neck cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:279–86. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Q, Jing N. Computational study on mechanism of G-quartet oligonucleotide T40214 selectively targeting Stat3. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2007;21:641–8. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jing N, Tweardy DJ. Targeting Stat3 in cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16:601–7. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnston PA, Grandis JR. STAT3 signaling: anticancer strategies and challenges. Mol Interv. 2011;11:18–26. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morishita R, Nakagami H, Taniyama Y, Matsushita H, Yamamoto K, Tomita N, et al. Oligonucleotide-based gene therapy for cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1998;36:529–34. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1998.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aoki M, Morishita R, Higaki J, Moriguchi A, Hayashi S, Matsushita H, et al. Survival of grafts of genetically modified cardiac myocytes transfected with FITC-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides and the beta-galactosidase gene in the noninfarcted area, but not the myocardial infarcted area. Gene Ther. 1997;4:120–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin MT, Chang CC, Chen ST, Chang HL, Su JL, Chau YP, et al. Cyr61 expression confers resistance to apoptosis in breast cancer MCF-7 cells by a mechanism of NF-kappaB-dependent XIAP up-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24015–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leong PL, Andrews GA, Johnson DE, Dyer KF, Xi S, Mai JC, et al. Targeted inhibition of Stat3 with a decoy oligonucleotide abrogates head and neck cancer cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4138–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0534764100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tadlaoui Hbibi A, Laguillier C, Souissi I, Lesage D, Le Coquil S, Cao A, et al. Efficient killing of SW480 colon carcinoma cells by a signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 hairpin decoy oligodeoxynucleotide--interference with interferon-gamma-STAT1-mediated killing. FEBS J. 2009;276:2505–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park YG, Nesterova M, Agrawal S, Cho-Chung YS. Dual blockade of cyclic AMP response element- (CRE) and AP-1-directed transcription by CRE-transcription factor decoy oligonucleotide. gene-specific inhibition of tumor growth. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1573–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bene A, Kurten RC, Chambers TC. Subcellular localization as a limiting factor for utilization of decoy oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nardozzi J, Wenta N, Yasuhara N, Vinkemeier U, Cingolani G. Molecular basis for the recognition of phosphorylated STAT1 by importin alpha5. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:83–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer T, Vinkemeier U. STAT nuclear translocation: potential for pharmacological intervention. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:1355–65. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.10.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costa-Pereira AP, Tininini S, Strobl B, Alonzi T, Schlaak JF, Is’harc H, et al. Mutational switch of an IL-6 response to an interferon-gamma-like response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8043–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122236099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schiavone D, Avalle L, Dewilde S, Poli V. The immediate early genes Fos and Egr1 become STAT1 transcriptional targets in the absence of STAT3. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2455–60. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Souissi I, Ladam P, Cognet JA, Le Coquil S, Varin-Blank N, Baran-Marszak F, et al. A STAT3-inhibitory hairpin decoy oligodeoxynucleotide discriminates between STAT1 and STAT3 and induces death in a human colon carcinoma cell line. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen X, Vinkemeier U, Zhao Y, Jeruzalmi D, Darnell JE, Jr., Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of a tyrosine phosphorylated STAT-1 dimer bound to DNA. Cell. 1998;93:827–39. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horvath CM, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr. A STAT protein domain that determines DNA sequence recognition suggests a novel DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1995;9:984–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lamb P, Seidel HM, Haslam J, Milocco L, Kessler LV, Stein RB, et al. STAT protein complexes activated by interferon-gamma and gp130 signaling molecules differ in their sequence preferences and transcriptional induction properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3283–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dolinnaya N, Metelev V, Oretskaya T, Tabatadze D, Shabarova Z. Hairpin-shaped DNA duplexes with disulfide bonds in sugar-phosphate backbone as potential DNA reagents for crosslinking with proteins. FEBS Lett. 1999;444:285–90. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laguillier C, Hbibi AT, Baran-Marszak F, Metelev V, Cao A, Cymbalista F, et al. Cell death in NF-kappaB-dependent tumour cell lines as a result of NF-kappaB trapping by linker-modified hairpin decoy oligonucleotide. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sen M, Thomas SM, Kim S, Yeh JI, Ferris RL, Johnson JT, et al. First-in-human trial of a STAT3 decoy oligonucleotide in head and neck tumors: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:694–705. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sen M, Tosca PJ, Zwayer C, Ryan MJ, Johnson JD, Knostman KA, et al. Lack of toxicity of a STAT3 decoy oligonucleotide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:983–95. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0823-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–12. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Becker S, Groner B, Müller CW. Three-dimensional structure of the Stat3beta homodimer bound to DNA. Nature. 1998;394:145–51. doi: 10.1038/28101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Valente AJ, Xie JF, Abramova MA, Wenzel UO, Abboud HE, Graves DT. A complex element regulates IFN-gamma-stimulated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene transcription. J Immunol. 1998;161:3719–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang YF, Yu-Lee LY. Multiple stat complexes interact at the interferon regulatory factor-1 interferon-gamma activation sequence in prolactin-stimulated Nb2 T cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;121:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(96)03840-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rouyez MC, Lestingi M, Charon M, Fichelson S, Buzyn A, Dusanter-Fourt I. IFN regulatory factor-2 cooperates with STAT1 to regulate transporter associated with antigen processing-1 promoter activity. J Immunol. 2005;174:3948–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pine R, Canova A, Schindler C. Tyrosine phosphorylated p91 binds to a single element in the ISGF2/IRF-1 promoter to mediate induction by IFN alpha and IFN gamma, and is likely to autoregulate the p91 gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:158–67. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caldenhoven E, Coffer P, Yuan J, Van de Stolpe A, Horn F, Kruijer W, et al. Stimulation of the human intercellular adhesion molecule-1 promoter by interleukin-6 and interferon-gamma involves binding of distinct factors to a palindromic response element. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21146–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nguyen VT, Benveniste EN. Involvement of STAT-1 and ets family members in interferon-gamma induction of CD40 transcription in microglia/macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23674–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujio Y, Kunisada K, Hirota H, Yamauchi-Takihara K, Kishimoto T. Signals through gp130 upregulate bcl-x gene expression via STAT1-binding cis-element in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2898–905. doi: 10.1172/JCI119484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dong Y, Rohn WM, Benveniste EN. IFN-gamma regulation of the type IV class II transactivator promoter in astrocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:4731–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gustafson KS, Ginder GD. Interferon-gamma induction of the human leukocyte antigen-E gene is mediated through binding of a complex containing STAT1alpha to a distinct interferon-gamma-responsive element. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20035–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stojanovic T, Wagner AH, Wang S, Kiss E, Rockstroh N, Bedke J, et al. STAT-1 decoy oligodeoxynucleotide inhibition of acute rejection in mouse heart transplants. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:719–29. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu W, Comhair SA, Zheng S, Chu SC, Marks-Konczalik J, Moss J, et al. STAT-1 and c-Fos interaction in nitric oxide synthase-2 gene activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L137–48. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00441.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marrero MB, Bencherif M. Convergence of alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-activated pathways for anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammation: central role for JAK2 activation of STAT3 and NF-kappaB. Brain Res. 2009;1256:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hückel M, Schurigt U, Wagner AH, Stöckigt R, Petrow PK, Thoss K, et al. Attenuation of murine antigen-induced arthritis by treatment with a decoy oligodeoxynucleotide inhibiting signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT-1) Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R17. doi: 10.1186/ar1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Magné S, Caron S, Charon M, Rouyez MC, Dusanter-Fourt I. STAT5 and Oct-1 form a stable complex that modulates cyclin D1 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8934–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.8934-8945.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wagner BJ, Hayes TE, Hoban CJ, Cochran BH. The SIF binding element confers sis/PDGF inducibility onto the c-fos promoter. EMBO J. 1990;9:4477–84. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bellido T, O’Brien CA, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC. Transcriptional activation of the p21(WAF1,CIP1,SDI1) gene by interleukin-6 type cytokines. A prerequisite for their pro-differentiating and anti-apoptotic effects on human osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21137–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Auernhammer CJ, Bousquet C, Melmed S. Autoregulation of pituitary corticotroph SOCS-3 expression: characterization of the murine SOCS-3 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6964–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kiuchi N, Nakajima K, Ichiba M, Fukada T, Narimatsu M, Mizuno K, et al. STAT3 is required for the gp130-mediated full activation of the c-myc gene. J Exp Med. 1999;189:63–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pallard C, Gouilleux F, Bénit L, Cocault L, Souyri M, Levy D, et al. Thrombopoietin activates a STAT5-like factor in hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:2847–56. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Campbell GS, Meyer DJ, Raz R, Levy DE, Schwartz J, Carter-Su C. Activation of acute phase response factor (APRF)/Stat3 transcription factor by growth hormone. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3974–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]