Abstract

The carcass of a stranded southern right whale Eubalaena australis, discovered on the coast of Golfo Nuevo in Península Valdés, Argentina, exhibited extensive orthotopic and heterotopic ossification, osteochondroma-like lesions, and early degenerative joint disease. Extensive soft tissue ossification led to ankylosis of the axial skeleton in a pattern that, in many respects, appeared more similar to a disabling human genetic disorder, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), than to more common skeletal system diseases in cetaceans and other species. This is the first reported case of a FOP-like condition in a marine mammal and raises important questions about conserved mechanisms of orthotopic and heterotopic ossification in this clade.

Keywords: Baleen whale, Ankylosis, Joint disease, Orthotopic/heterotopic ossification, Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, FOP

INTRODUCTION

Southern right whales Eubalaena australis (SRW) are found in all oceans of the southern hemisphere, where they migrate between winter coastal nursery grounds and, generally unknown, summer feeding grounds (International Whaling Commission 2001). Nursery grounds are used primarily by adult females for raising their calves during the first 3 mo of life (Payne 1986, Best 1994). Most SRW calving grounds are located in near-shore waters off the southern coasts of Australia and South Africa and off the Argentine coast of South America, primarily between 20 and 45°S (International Whaling Commission 2001).

More right whales die and strand each year on the beaches of Península Valdés in northeast Patagonia than in any other region of the world, making this a unique area to evaluate the health of right whales through post mortem examinations (Uhart et al. 2008). The Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program (SRWHMP) was established in 2003 with the objective of monitoring the health and mortality of SRW in Península Valdés. The SRWHMP conducts systematic beach surveys throughout the calving period when right whales are abundant (June through December) to locate and study beached whale carcasses. Between June 2003 and December 2011, the SRWHMP documented 489 SRW carcasses along the coasts of Península Valdés (V. J. Rowntree et al. unpubl. data). Of these, 12% were adult whales.

Vertebral pathology has been widely documented in captive (e.g. Morton 1978, Alexander et al. 1989) and wild cetaceans (e.g. Kompanje 1995a,b, 1999, Berghan & Visser 2000, Kompanje & Garcia Hart-mann 2001, Sweeny et al. 2005, Rothschild 2005a,b, Félix et al. 2007, Galatius et al. 2009, Groch et al. 2012) from both baleen (Mysticeti) and toothed whales (Odontoceti). All reported bone or joint diseases described to date have been localized to the vertebral column and were shown or presumed to be degenerative, bacterial, or inflammatory in origin. To date, widespread systemic bone disease has not been described in marine mammals. This work represents the first documented case of severe, generalized orthotopic and heterotopic ossification in a right whale.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted on a stranded adult male SRW Eubalaena australis found on 14 October 2003 on the coast of Golfo Nuevo (42°46′S, 64° 15′W) in Península Valdés, Argentina. The whale was not necropsied when initially found due to logistical constraints. However, morphometric measurements were obtained at that time, and the whale was left to decompose. The skeletal remains of the animal were relocated the following year. Due to the bulk and weight of the carcass, the nearly complete ankylosis of the vertebrae (see ‘Results’), and our inability to conduct a thorough pathological evaluation in situ, sections of affected vertebra were removed from the carcass on the beach. A bow saw and electric drill were used to obtain multiple bone samples from both healthy and diseased areas of each vertebra for further gross examination. Additionally, core bone samples were stored in cryogenic tubes and kept frozen (−20°C) until assayed for the presence of Brucella spp.

Molecular testing for Brucella spp

Brucella spp. infection is widespread in wild populations of marine mammals, with serological/microbiological evidence being reported in the Northern Hemisphere and Arctic since 1989, and in the Antarctic since 1998 (Retamal et al. 2000). Brucellae can cause primary disease in mammals, such as spondylitis (see ‘Discussion’). Under appropriate conditions (pH > 4, high humidity, low temperature and absence of direct sunlight), Brucella spp. can survive in the environment for very long periods compared with most other non-sporing pathogenic bacteria (Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Brucellosis 1986). Based on this background, Brucella spp. infection was investigated as the most likely infectious cause of the pathology observed.

Sections (1 cm in length) of 3 core bone samples from 3 severely affected vertebrae were frozen in liquid nitrogen, pulverized, and finely ground. A suspension of 250 mg of powder in 400 μ1 ATL lysis buffer and 40 μl Proteinase K from a commercial DNA extraction kit (DNeasy, Qiagen) was prepared and incubated in a heat block at 55°C for 72 h. A buffer (400 μl) was added to each sample, and the resulting suspension was incubated at 70°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 14 000 rpm (18188 × g) for 3 min. The supernatant (900 μl) was extracted according to kit protocol and eluted in 100 μl. Multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as previously described (Sidor et al. in press). Briefly, this multiplex targets the Brucella genus–specific bcsp31 gene, with internal controls for amplification and mammalian host mitochondrial DNA integrity. Six replicates of DNA from each bone core sample were assayed. Positive DNA (Brucella pinnipedialis, 1, 10, 100, 1000, and 10 000 fg) and negative (no template) controls were included.

RESULTS

On 14 October 2003, a SRW Eubalaena australis carcass was found during a routine beach survey (42° 46′11.3″ S, 64° 15′12.0″ W) for live stranded or dead whales. The whale was an adult male measuring 15.25 m (snout to fluke notch). Based on a predefined set of criteria used to score decomposition stages such as bloating, rancid stench, sloughing of skin, and absence of whale lice (i.e. cyamids) on the head callosities, the whale was thought to have been dead for at least 10 d when found (Geraci & Loundsbury 1993). On external examination, there was no indication of human-related mortality factors, such as vessel collision or entanglement in fishing gear.

When relocated and re-examined approximately 1 yr later, the carcass was in an advanced state of decomposition. The remains consisted only of the skeleton and portions of dry leathery skin, which was draped over the skeletal remains and collapsed body cavities. A fairly complete examination of the animal‘s skeletal system, which was markedly abnormal, was possible due to exposure of the skeleton.

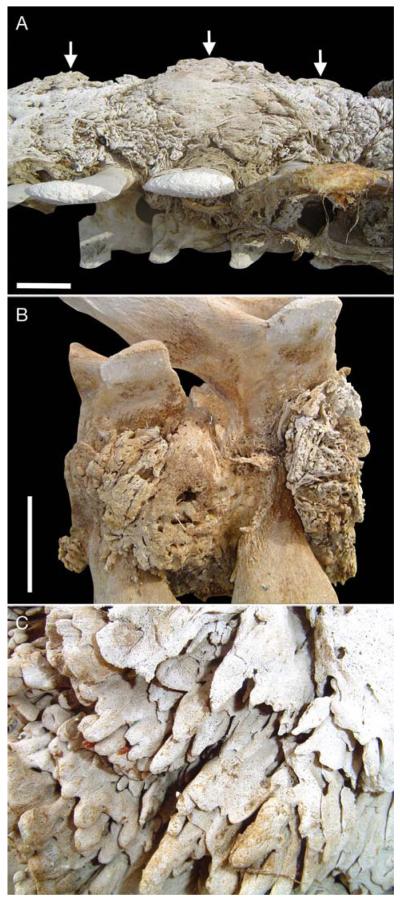

Predominant pathological findings included: (1) heterotopic bone (bone arising from soft tissue), (2) orthotopic bone (bone arising from the normotopic skeleton), (3) osteochondroma-like lesions, and (4) early degenerative joint disease. In general, cervical (1 to 7), thoracic (1 to 14), lumbar (1 to 15), and many of the caudal (1 to 20) vertebrae were fused by rigid synostoses composed of massive amounts of irregular sheets of heterotopic (Fig. 1A–C) and orthotopic bone (Fig. 2A,B). This bone was mature and cancellous along the lateral aspect of the affected thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, and cortical along the ventral side of the vertebral column. The thoracic and lumbar vertebrae were the most severely affected.

Fig. 1. Eubalaena australis.

(A) Massive heterotopic ossifications (arrows) on ventral side of lumbar area (vertebral column upside down). Scale bar = 10 cm. (B) Lumbar vertebrae affected by heterotopic ossifications leading to ankylosis.

Scale bar =15 cm. (C) Detail of heterotopic bone

Fig. 2. Eubalaena australis.

(A) Epiphysis of lumbar vertebra showing quasi-circumferential orthotopic ossification. Scale bar = 15 cm. (B) Dense orthotopic bone forming a smooth-surfaced groove along the ventral side of lumbar vertebrae corresponding with the location the abdominal aorta (solid arrow), and paired conduits corresponding with the location of the lumbar arteries (dashed arrows). Scale bar =10 cm. (C) Proximal epiphysis of ulna (elbow joint) and olecranon process (OP) affected by orthotopic ossification (arrow). HU: humeroulnar joint. Scale bar = 5 cm. (D) Humeri with abundant orthotopic ossifications on diaphyses (solid arrows) and epiphyses near the elbow joint (dashed arrows). HS: humero-scapular joint; HR: humeroradial joint; HU: humeroradial joint. Scale bar = 10 cm

Orthotopic bone formed an approximately 11 cm in diameter, regular, smooth-surfaced groove along the ventral aspect of the affected lumbar vertebrae that was traceable to Caudal Vertebrae 13. This groove corresponded with the location of the abdominal aorta. Several, ca. 5 to 7 cm diameter, paired conduits that were embedded in dense orthotopic bone originated in the aforementioned groove and extended dorsolaterally between contiguous transverse processes on both sides of the spine (Fig, 2B). These conduits corresponded with the location of lumbar arteries. In addition, orthotopic ossification also affected the pedicles of vertebral arches, transverse processes, and several zygapophyseal joints. Orthotopic ossification was also present in the appendicular skeleton. The diaphysis and distal epiphyseal margin (near the humeroradioulnar joints) of both humeri, and the proximal epiphyses of both ulnae (elbow joints) including the olecranon processes, were affected by abundant osteophytes (Fig. 2B,C). Other bones of the appendicular system were missing and could not be examined.

Some lesions strongly suggested the presence of osteochondromas, which were observed as pedunculated osteophytes on the anterior aspect of the vertebral pedicles (Fig. 3A) and on the epiphyses of caudal vertebrae (Fig. 3B) and radioulnar joints (Fig. 3C). Early degenerative joint disease was observed in proximal radioulnar joint (Fig. 3C), lumbar, and thoracic intervertebral disc spaces (Fig. 4A) and in the distal articular surface of the ulnocarpal joints (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3. Eubalaena australis.

Osteochondroma-like lesions (A) on the anterior aspect of the pedicle of a thoracic vertebra (arrow). Scale bar = 5 cm. (B) Lesions on 2 caudal vertebrae (arrows), and (C) on the upper ulnar epiphysis (white arrow). Note the degenerative changes of subchondral articular bone (black arrow) on the radicular (RU) joint. Scale bar = 3 cm

Fig. 4. Eubalaena australis.

Degenerative joint disease lesions (A) on a thoracic intervertebral disc space (black arrows) along with ossification of transverse process (white arrow). Scale bar = 8 cm. (B) Lesions on the distal articular surface of an ulnocaipal joint (arrow). Scale bar = 5 cm

Detection of Brucella spp. DNA from core bone samples by PCR was negative in all samples and replicates. Internal controls amplified successfully in all samples. The threshold cycle (Ct) for the plasmid amplification control (1 fg) for bone samples was 38.8 ± 2.3 (n = 9), compared to 40.6 ± 2.2 (n = 60) for non-bone samples in the same plate, indicating no inhibition of amplification for the bone samples. The mitochondrial control Ct averaged 27.8 ±1.2 for all bone replicates compared to 13.4 ± 2.2 for fresh tissue (marine mammal liver, spleen, and lymph node), indicating a low quantity but adequate quality of host mitochondrial DNA for amplification. Positive controls down to concentrations of 1 fg DNA per reaction successfully amplified, and simultaneous internal PCR controls indicate adequate host mitochondrial DNA quantity and quality. Negative controls did not amplify.

Thirty carcasses of adult SRW were found by the SRWHMP between 2003 and 2011. However, due to logistical constraints, the skeleton of most of these whales could not be examined with the exception of the case presented here.

DISCUSSION

This dramatic case represents the first report of widespread skeletal system disease in a cetacean and the first report of skeletal system disease in a SRW Eubalaena australis. Pathology of the vertebral column and associated structures reported in other cetaceans includes: (1) discarthrosis and zygarthrosis (spondylarthrosis or spondylosis deformans) (Paterson 1984, Kompanje 1995a,b, 1999, Kompanje & Garcia Hartmann 2001), (2) infectious spondylitis (spondylo-osteomyelitis) (Kompanje 1995b, 1999, Sweeny et al. 2005, Félix et al. 2007), (3) spondyloarthritis (spondyloarthropathy) (Kompanje 1999, Rothschild 2005a,b, Galatius et al. 2009), and (4) osteitis deformans (Sweeny et al. 2005). To date, most of the described vertebral anomalies of cetaceans have been thought to be the result of degenerative processes associated with aging (spondylarthrosis) or to bacterial infection (spondylo-osteomyelitis) (Kompanje 1995b).

Bacteria such as Brucella spp., Salmonella spp., and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are associated with spondylitis in humans (Govender & Schweitzler 2003, McLain & Isada 2004, Pappas et al. 2005), dogs (Anderson & Binnington 1983), snakes (Isaza et al. 2000), and pigs (Doige 1980). These are common pathogens of marine mammals, affecting both cetaceans and pinnipeds (Jahans et al. 1997, Higgins 2000). In the present study, identification of Brucella spp. was attempted by PCR, although with negative results. This finding could be confounded by the delay in sample collection (14 mo) while the carcass remained exposed to the elements on the beach. However, our PCR results indicated adequate host mitochondrial DNA quantity and quality, whereas stability of Brucella spp. DNA has been experimentally shown to exceed that of the host (Sidor et al. in press).

Infectious spondylitis is usually limited to a few intervertebral joints, causes limited orthotopic, but not widespread heterotopic ossification, leads to characteristic bone changes such as irregular destruction of adjacent vertebral end-plates, and does not typically involve the appendicular skeleton (Kompanje 1999). The ossification observed in the present case was both orthotopic and heterotopic in nature and was more widespread and atypical than what has been described or would be expected in bacterial spondylitis in other cetaceans or pinnipeds, or in other species.

Primary degenerative conditions, such as spondy-loarthrosis, were also considered as possible causes for the extensive bony lesions in the present case. Spondyloarthrosis results from degeneration of the intervertebral disc, is often associated with aging, and occurs only in adult animals (Kompanje 1995b). This degenerative process is often followed by reactive chondro-osseous changes (discarthrosis) such as vertically formed marginal osteophytes, sclerosis, and erosion of the vertebral end plates. The costovertebral or apophyseal joints are not affected, and the intervertebral discs do not typically calcify (Resnick & Niwayama 1988). Although we were not able to evaluate the integrity of all intervertebral spaces in the studied whale, vertebral end plates showed early degenerative joint disease, and thus some degree of spondyloarthrosis may have been present.

The widespread occurrence, pattern of orthotopic and heterotopic bone formation, and severity of boney changes in the current case appear somewhat unique when compared to all other bone diseases described in the marine mammal literature. Although some degree of spondyloarthrosis was evident in our case, this entity alone does not explain the scope or severity of the pathology observed. Therefore, in addition to comparisons between our case and descriptions of the most common causes of bone lesions in cetaceans, including spondylitis, discarthrosis/zygarthrosis, and spondyloarthritis (Kompanje 1995a,b, 1999), comparisons to skeletal pathologies affecting other taxa were performed in an effort to identify conditions with exuberant orthotopic and heterotopic ossification similar to that in the current case.

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), a disabling heritable disorder of connective tissue in humans, is characterized by congenital malformation of the great toes and progressive heterotopic ossification of the skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fascia, which leads to progressive and eventually catastrophic disability (Shore & Kaplan 2010). Kaplan et al. (1990) described the usual progression of ectopic ossification in humans, which almost invariably begins in the upper cervical and paraspinal muscles and later affects the appendicular skeletal muscles and those of the lower limbs. Heterotopic bone in FOP forms rigid synostoses with the normotopic skeleton (Cohen et al. 1993, Rocke et al. 1994). Once heterotopic bone is mature, it often contains marrow elements, and can take the gross form of the soft tissues it replaces as distinct ossicles. Among other important pathological features of FOP in humans are: congenital or early postnatal fusion of the facet joints (zygapophyseal) of predominantly cervical vertebra; malformations of the temporomandibular joints; malformations of the ribs and fusion of costovertebral joints; short, broad femoral necks; proximal medial tibial osteochondromas and other osteochondromas; clinodactyly, and variable hearing loss (mostly conductive) (Kaplan et al. 2005). Progression of FOP is episodic and often associated with soft tissue trauma, although bone-forming events may be spontaneous. Disability is cumulative.

FOP and its underlying genetic basis are well documented in humans. In all classically affected individuals worldwide, FOP is caused by a recurrent single nucleotide missense activating heterozygous mutation in the gene encoding Activin Receptor IA/Activin-like Kinase 2 (ACVR1/ALK2), a bone morphogenetic protein Type I receptor (Shore et al. 2006). The mutated FOP gene encodes a novel Type I receptor that dysregulates bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, thus leading to profound heterotopic ossification (Kaplan et al. 2009). FOP-like heterotopic ossification has been reported in dogs, pigs, and cats (McKusick 1972, Gannon et al. 1998, Kan & Kessler 2011), and reptiles and amphibians with heterotopic bone have also been described (Wild 1997, Gilbert et al. 2001, Organ 2006). However, the molecular basis for the disease in these species is not yet known. Additionally, heterotopic ossification can be induced in mice (Kan et al. 2004) and chickens (Zhang et al. 2003), and FOP-like pheno-types have been reported in genetically engineered zebrafish embryos (Shen et al. 2009).

The present case, the significant features of which include extensive orthotopic and heterotopic ossification, resultant ankylosis, dorsal, axial, and proximal distribution of heterotopic ossification involving tendons, fascia, ligaments, aponeuroses, skeletal muscle, multicentric occurrence of osteochondroma-like lesions, and the presence of degenerative joint disease, shares many similarities with FOP in humans (Kaplan et al. 2005). However, because most of the appendicular bones of this whale could not be studied, many of the pathological features of FOP in humans could not be confirmed or excluded. Although this whale had many features of FOP, we cannot determine with certainty whether it had FOP as neither histologic confirmation of formative lesions nor DNA sequence analysis could be attempted because the whale’s carcass had been washed away by the tide by the time FOP was suspected 8 yr after death.

A genetic disorder of heterotopic ossification that occurs in humans and could be confidently excluded here is progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH), a rare condition characterized by early cutaneous ossification with progression to deeper connective tissues, extensive deformity of the normotopic skeleton, and dramatic asymmetry of lesional distribution (Shore & Kaplan 2010). In our case, although we do not have early histological evidence to determine the pathway of bone formation, lesions did not involve the skin, did not cause deformity of the normotopic skeleton, and were symmetrical.

The body axis (i.e. vertebral column, spinal muscles of the back, and tail flukes) represent the main locomotion organs of whales (Slijper 1979), and the integrity of these structures allows flexibility for swimming, feeding, copulating, and other functions. It is very likely that the extensive pathology along the entire length of the vertebral column of this whale compromised these activities. Extensive bone proliferation may also have contributed to compression of spinal nerves, especially in the intervertebral spaces, and important blood vessels that form the central irrigation system such as the aorta and vena cava.

A wide range of terrestrial and aquatic vertebrates possesses the genetic, cellular, and molecular pathways to form heterotopic bone. The presence of extensive heterotopic ossification in a marine mammal has important biological significance regardless of the genetic or molecular basis of the lesions. Our report of a FOP-like condition in a southern right whale extends the observation of heterotopic ossification and tissue metamorphosis (Kaplan et al. 2009) to a marine mammal that occupies a unique ecological niche in the natural world.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Office of Protected Resources of the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (Orders DG133F-02-SE-0901, DG-133F-06-SE-5823, and DG133F07 SE4651) for funding the Southern Right Whale Health Monitoring Program (SRWHMP) at Península Valdés during the years 2003, 2004, and 2005. We also thank SRWHMP partner institutions, Instituto de Conservation de Ballenas/Whale Conservation Institute, Wildlife Conservation Society, Fundacion Patagonia Natural and Fundacion Ecocentro, and the SRWHMP Stranding Network, Direction de Fauna y Flora Silvestres, Directión General de Conservatión de Áreas Protegidas. The Administratión del Área Natural Pro-tegida Península Valdés provided the necessary permits to conduct this study. We thank Soledad La Sala for digital image processing. This work was also supported in part by the International Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Association, the Center for Research in FOP and Related Disorders, the Isaac & Rose Nassau Professorship of Orthopaedic Molecular Medicine, and by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH R01-AR41916).

LITERATURE CITED

- Alexander JW, Solangi MA, Riegel LS. Vertebral osteomyelitis and suspected diskospondylitis in an Atlantic bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) J Wildl Dis. 1989;25:118–121. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-25.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GI, Binnington AG. Discospondylitis and orchitis associated with high Brucella titre in a dog. Can Vet J. 1983;24:249–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghan J, Visser IN. Vertebral column malformations in New Zealand delphinids with review of cases worldwide. Aquat Mamm. 2000;26:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Best P. Seasonality of reproduction and the length of gestation in southern right whales Eubalaena australis. J Zool (Lond) 1994;232:175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RB, Hahn GV, Tabas JA. The natural history of heterotopic ossification inpatients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. A study of forty-four patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:215–219. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doige CE. Discospondylitis in swine. Can J Comp Med. 1980;44:121–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félix F, Haase B, Aguirre WE. Spondylitis in a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) from the southeast Pacific. Dis Aquat Org. 2007;75:259–264. doi: 10.3354/dao075259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatius A, Sonne C, Kinze CC, Dietz R, Beck Jensen JE. Occurrence of vertebral osteophytes in a museum sample of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) from Danish waters. J Wildl Dis. 2009;45:19–28. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-45.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon FH, Valentine BA, Shore EM, Zasloff MA, Kaplan FS. Acute lymphocytic infiltration in an extremely early lesion of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;346:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci JR, Loundsbury VJ. Marine mammals ashore: a field guide for strandings. Texas A & M Sea Grant Program; Galveston, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SF, Loredo GA, Brukman A, Burke AC. Morphogenesis of the turtle shell: the development of a novel structure in tetrapod evolution. Evol Dev. 2001;3:47–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003002047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govender S, Schweitzler G. Salmonella spondylitis in inflammatory disorders of the spine. In: Govender S, editor. Inflammatory diseases of the spine. TTG Asia Media Pty; Singapore: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Groch KR, Marcondes MCC, Colosio AC, Catão-Dias JL. Skeletal abnormalities in humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae stranded in the Brazilian breeding ground. Dis Aquat Org. 2012;101:145–158. doi: 10.3354/dao02518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins R. Bacteria and fungi of marine mammals: a review. Can Vet J. 2000;41:105–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Whaling Commission Report of the workshop on the comprehensive assessment of right whales: a worldwide comparison. J Cetacean Res Manag. 2001;2(Spec Issue):1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Isaza R, Garner M, Jacobsen E. Proliferative osteoarthritis and osteoarthrosis in 15 snakes. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2000;31:20–27. doi: 10.1638/1042-7260(2000)031[0020:POAOIS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahans KL, Foster G, Broughton ES. The characterization of Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals. Vet Microbiol. 1997;57:373–382. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Brucellosis . Sixth report, Technical Report Series 740. WHO; Geneva: 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan L, Kessler JA. Animal models of typical heterotopic ossification. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2011/309287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan L, Hu M, Gomes WA, Kessler JA. Transgenic mice overexpressing BMP4 develop a fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP)-like phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63372-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan FS, Tabas JA, Zasloff MA. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: A clue from the fly? Calcif Tissue Int. 1990;47:117–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02555995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan FS, Glaser DL, Shore EM, Deirmengian GK. The phenotype of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2005;3:183–188. others. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan FS, Pignolo RJ, Shore EM. The FOP metamorphogene encodes a novel type I receptor that dysregulates BMP signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinze CC. Note on the occurrence of spondylitis deformans in a sample of harbor porpoises Phocoena phocoena (L.) taken in Danish waters. Aquat Mamm. 1986;12:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kompanje EJO. On the occurrence of spondylosis deformans in white-beaked dolphins Lagenorhynchus albirostris (Gray, 1846) stranded on the Dutch coast. Zool Med Leiden. 1995a;69:231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kompanje EJO. Differences between spondylo-osteomyelitis and spondylosis deformans in small odontocetes based on museum material. Aquat Mamm. 1995b;21:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kompanje EJO. Considerations on the comparative pathology of the vertebrae in Mysticeti and Odontoceti; evidence for the occurrence of discarthrosis, zygarthrosis, infectious spondylitis and spondylarthritis. Zool Med Leiden. 1999;73:99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kompanje EJO, Garcia Hartmann M. Intraspongious disc herniation (Schmorl‘s node) in Phocoena phocoena and Lagenorhynchus albirostris (Mammalia: Cetacea, Odonticeti) Deinsea. 2001;8:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- McKusick VA. Other heritable and generalized disorders of connective tissue. In: Beighton, editor. Heritable disorders of connective tissue. CV Mosby Company; St. Louis, MO: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- McLain RF, Isada C. Spinal tuberculosis deserved a place on the radar screen. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:537–549. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.7.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton B. Osteomyelitis (pyogenic spondylitis) of the spine in a dolphin. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978;173:1119–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organ CL. Thoracic epaxial muscles in living archosaurs and ornithopod dinosaurs. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:782–793. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, Tsianos E. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2325–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson RA. Spondylitis deformans in a Bryde‘s whale (Balenoptera edeni Anderson) stranded on the southern coast of Queensland. J Wildl Dis. 1984;20:250–252. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-20.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne R. Long term behavioral studies of the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) Rep Int Whal Comm. 1986;10(Spec Issue):161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick D, Niwayama G. Degenerative diseases of the spine. In: Manke D, editor. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders: articular diseases. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Retamal P, Blank O, Abalos P, Torres D. Detection of anti-Brucella antibodies in pinnipeds from the Antarctic territory. Vet Rec. 2000;146:166–167. doi: 10.1136/vr.146.6.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocke DM, Zasloff M, Peeper J. Age-and-joint specific risk of initial heterotopic ossification in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;301:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild BM. What causes lesions in sperm whale bones? Science. 2005a;308:631–632. doi: 10.1126/science.308.5722.631c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild BM. Whale of a tale. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005b;64:1385–1386. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Little SC, Xu M, Haupt J. The fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva R206H ACVR1 mutation activates BMP-independent chondrogenesis and zebrafish embryo ventralization. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3462–3472. doi: 10.1172/JCI37412. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Inherited human diseases of heterotopic ossification. Nature Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006;38:525–527. doi: 10.1038/ng1783. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidor IS, Dunn JL, Tsongalis GJ, Carlson J, Frasca S. A multiplex real-time PCR assay with two internal controls for the detection of Brucella spp. in tissues, blood and feces from marine mammals. J Vet Diagn Invest. 25(1) doi: 10.1177/1040638712470945. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slijper EJ. Whales. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeny MM, Price JM, Jones GS, French TW, Early GA, Moore MJ. Spondylitic changes in long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) stranded on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA, between 1982 and 2000. J Wildl Dis. 2005;41:717–727. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-41.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhart M, Rowntree VJ, Mohamed N, Pozzi L. Strandings of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) at Península Valdés, Argentina from 2003-2007. International Whaling Commission; Cambridge: 2008. others. [Google Scholar]

- Wild ER. Description of the adult skeleton and developmental osteology of the hyperossified horned frog (Anura: Leptodactylidae) J Morphol. 1997;232:169–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199705)232:2<169::AID-JMOR4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Schwarz EM, Rosier RN, Zuscik MJ, Puzas JE, O‘Keefe RJ. ALK2 functions as a BMP type I receptor and induces Indian hedgehog in chondrocytes during skeletal development. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1593–1604. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]