Abstract

Objectives. We took advantage of a 2-intervention natural experiment to investigate the impacts of neighborhood demolition and housing improvement on adult residents’ mental and physical health.

Methods. We identified a longitudinal cohort (n = 1041, including intervention and control participants) by matching participants in 2 randomly sampled cross-sectional surveys conducted in 2006 and 2008 in 14 disadvantaged neighborhoods of Glasgow, United Kingdom. We measured residents’ self-reported health with Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey version 2 mean scores.

Results. After adjustment for potential confounders and baseline health, mean mental and physical health scores for residents living in partly demolished neighborhoods were similar to the control group (mental health, b = 2.49; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −1.25, 6.23; P = .185; physical health, b = −0.24; 95% CI = −2.96, 2.48; P = .859). Mean mental health scores for residents experiencing housing improvement were higher than in the control group (b = 2.41; 95% CI = 0.03, 4.80; P = .047); physical health scores were similar between groups (b = −0.66; 95% CI = −2.57, 1.25; P = .486).

Conclusions. Our findings suggest that housing improvement may lead to small, short-term mental health benefits. Physical deterioration and demolition of neighborhoods do not appear to adversely affect residents’ health.

The quality of residential environments, at both the home and the neighborhood level, is associated with residents’ physical and mental health.1–7 Some longitudinal studies suggest that exposure to poor housing8 or to neighborhood-level deprivation9–18 increases the risk of morbidity or mortality beyond what might be predicted from individual-level socioeconomic factors. A causal association between residential environments and health would have important public health implications: improvements to residential environments might contribute positively to public health goals, and deteriorating residential environments could be harmful.

Policymakers expect that improving home and neighborhood environments, particularly in disadvantaged areas, will benefit population health and help reduce health inequalities.19,20 Terms such as urban renewal and regeneration are used to describe a range of interventions, such as home improvement programs, housing clearance and demolition, and neighborhood-level improvements.19

Research supports assumptions that housing-led urban renewal benefits residents’ health.21–29 A systematic review found that improvements in respiratory, general, and mental health followed housing improvement, with particularly robust evidence of health benefits relating to warmth-improvement interventions.21,30–32 More recently, an evaluation of a multisite urban renewal program in the United Kingdom found relative improvements in residents’ Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey mental health scores and self-reported general health at 10-year follow-up.33

However, the evidence base is neither comprehensive nor conclusive, particularly regarding neighborhood-level renewal. Reviews have noted some evidence that such interventions may have unintended consequences.34 A study of neighborhood renewal in the United Kingdom found that self-reported health satisfaction worsened, possibly reflecting the intervention’s failure to deliver sufficient changes to residents’ lives and opportunities.35 A recent series of reviews identified 11 interventions considered to have sufficient evidence of effectiveness to warrant implementation,24–28 only 1 of which was a neighborhood-level intervention (rental vouchers to assist relocations to more desirable areas36). The reviews identified 34 interventions of unknown or inconclusive health effects and 7 that were potentially ineffective.24 Neighborhood-level interventions such as demolishing and revitalizing poor public housing (e.g., HOPE VI37), relocating residents, and various forms of neighborhood redesign yielded too little evidence to draw conclusions.28

Some commentators have emphasized the social harms linked to housing clearance and demolition programs.38 Paris and Blackaby note that such programs have “frequently been accused of the ‘destruction of communities.’”39(p18) This alleged destruction is partly a social phenomenon involving the separation of neighbors and closing down of amenities that may have been used as social hubs (e.g., schools, community centers, cafés). It is also a physical phenomenon that increases the proportion of derelict properties and turns neighborhoods into worksites and buildings into rubble.39,40 Furthermore, large-scale clearances can take years to complete, while residents waiting to be relocated are exposed to steadily worsening neighborhood environments.41 If deteriorating residential environments are harmful to health, then residents who remain in neighborhoods undergoing demolition risk being harmed. However, we have not identified any experimental or quasi-experimental study that focuses on the potentially harmful effects of continued residence in neighborhoods undergoing demolition and clearance.

We studied a multifaceted renewal program implemented across the city of Glasgow, United Kingdom. In many neighborhoods, existing properties were improved to meet new government standards. However, some neighborhoods began a long-term process of demolition and rebuilding, and residents often lived for several years in neighborhoods undergoing clearance and demolition while they awaited relocation to better-quality housing.42 We treated housing improvement and the experience of living in a demolition area as 2 distinct natural experiments, and we used quasi-experimental methods to test our hypotheses: (1) residents who spent 2 years living in neighborhoods undergoing clearance and demolition would experience worsening health, and (2) residents who experienced housing improvement (and who did not live in neighborhoods undergoing clearance and demolition) would experience improved physical and mental health.

METHODS

We analyzed data collected for a larger research program, GoWell.42 We assembled a nonrandomized control group and 2 separate intervention groups. We were not responsible for intervention planning, implementation, or allocation. Our study can therefore be described as a quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment.43,44

We surveyed 14 disadvantaged neighborhoods in the city of Glasgow (Appendix A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). We identified and defined the neighborhoods in consultation with local government and housing organizations.45 All selected neighborhoods met the Scottish Government definition of disadvantaged: the lowest 15% in the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.46 Around 3 in every 4 homes (74.5% at baseline) across the GoWell areas were socially rented, defined as homes that are rented at relatively low rates to people in housing need; they are generally provided through the public sector by local councils or through not-for-profit organizations.42

Interventions

Demolition group.

Area transformation programs, involving clearance and demolition, took place in 4 GoWell neighborhoods involving around 5800 dwellings. Although the long-term goal was to place residents into better-quality homes and neighborhoods, the lengthy implementation process (> 10 years) required many households to remain for years in neighborhoods undergoing destruction: we referred to these as remainer households. During the study period, 1698 (29.3%) homes from these 4 neighborhoods were cleared and either prepared for demolition or actually demolished. Most of the remaining homes were either scheduled for clearance or had decisions pending, making this an uncertain and disruptive time for remainers. Around a third of remainers’ properties received limited housing improvements during this time, most commonly the provision of secure front doors.

Housing improvement group.

In 10 GoWell neighborhoods (totaling ∼12 000 dwellings) an extensive program of housing improvement was driven by national and local changes to housing quality standards.47 In accordance with need identified by surveyors, properties received internal and external improvements such as better roofs, external cladding, doors, windows, bathrooms, kitchens, heating, and electrical systems.48 Government-regulated not-for-profit housing organizations known as registered social landlords (RSLs) were required to ensure that all their properties met the new standards by 2015. RSLs manage social rented and, to a lesser extent, owner-occupied properties. The scale of the improvement program required an incremental approach spanning the available time, in effect creating a waiting list. In 2008, 36% of GoWell householders reported receiving housing improvement during the previous 2 years.48

Control group.

Control group householders resided in the same 10 neighborhoods as the housing improvement group but did not report receiving housing improvement between 2006 and 2008, because their homes were either ineligible or still waiting for improvement. RSLs owned eligible properties or (in the case of private-sector homes) contracted to provide services. The length of time residents had to wait for improvements was driven by logistical concerns and incremental decisions made by several different organizations. RSLs hired local private contractors to assess homes and deliver improvements in different parts of the city; the ordering of works depended on the assembling of streets of properties into practical contracts and programs, rather than on any interpretation of need (either of the property or the occupant). As with many natural experiments, assignment to intervention and control groups was therefore complex but not random.

Survey

We collected data from the 14 neighborhoods in May to July of 2006 (wave 1) and 2008 (wave 2). The 2-year length of follow-up provided an opportunity to study the interventions at a stage when sufficient numbers of participants were still awaiting (1) home improvements (i.e., the control group) or (2) relocation from demolition neighborhoods. We randomly selected addresses from postal address files at each wave. We randomly sampled 1 adult householder (aged ≥ 16 years) per household for home face-to-face interviews.42

We identified the longitudinal cohort retrospectively. We used manual and electronic methods to match participants who took part in both the 2006 and 2008 surveys by name, address, age, gender, and household structure. A second researcher checked initial matches. All participants gave written consent. We handled data in accordance with data protection principles.

Variables

Health.

We assessed self-reported mental and physical health with Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-12v2) mean scores.49 The SF-12v2 is a validated questionnaire: scores are computed from responses to 12 questions and range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health.49 The SF-12v2 also includes 8 subscales for use in exploratory analysis: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health.

Potential confounders.

Our analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors known to vary between GoWell neighborhoods: gender, age (16–39, 40–64, or > 64 years), education (no qualification or some qualification), household structure (adult only or living with children), housing status (owner occupied or rented), and building type (house, low-rise apartment building, or high-rise apartment building). We also included country of birth (born in the United Kingdom or born outside the United Kingdom) because most of the ethnic variation within the GoWell sample resulted from first-generation immigration, particularly economic migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.42,48 We derived these variables from items in the GoWell questionnaire for both survey waves and collapsed categories for our analysis (Appendix B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). The 2008 survey also included a question on housing improvement in the previous 2 years. All variable measures derived from participant self-reports, with 2 exceptions: we assessed building type and area of residence ourselves.

Analyses

The primary outcomes for the analysis were mean physical and mental health SF-12v2 scores at wave 2 in the 2 intervention groups, relative to the control group, which received neither intervention. We decided a priori to adjust for wave 1 SF-12v2 measurements, gender, age, education, household structure, housing status, building type, and country of birth, the factors we considered likely to affect health. Of the 1041 individuals included in the data set, only 8 had any missing data.

We used Stata/IC 11.1 for all analyses on the subset of complete data.50 We used robust standard errors to construct multiple regression models to account for clustering of respondents within each area. We conducted tests for interactions between main effects and participant characteristics (age, gender, country of birth, household structure, and education). We also performed exploratory analysis of SF-12v2 subscales.

RESULTS

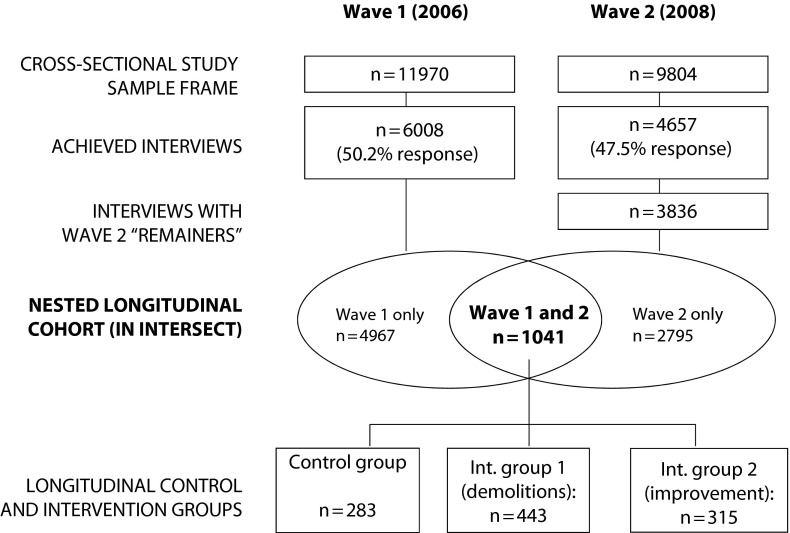

We identified 1041 participants who had remained in their neighborhood between 2006 and 2008 and participated in both surveys (control group, n = 283; demolition group, n = 443; housing improvement group, n = 315; Figure 1). The housing improvement and control groups shared broadly similar demographic characteristics at baseline, except for significantly greater proportions of social renters and high-rise apartment dwellers in the housing improvement group (Table 1). The demolition group had more social renters, high-rise dwellers, younger participants, households with children, immigrants, and participants with educational qualifications than the control group. Mean SF-12v2 physical scores were higher (better) in the demolition than in the control group at baseline; mean SF-12v2 mental health scores were similar across all 3 groups at baseline. A comparison of the longitudinal sample and cross-sectional population measures is shown in Appendix C, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Flowchart describing cross-sectional survey sample and nested longitudinal sample: GoWell Surveys, 2006–2008.

Note. Int. = intervention.

TABLE 1—

Summary Statistics Comparing Residents of Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Undergoing Demolition or Housing Improvement With Control Group at Wave 1: GoWell Survey, 2006

| Variable | Control Group (n = 283), % or Mean Score | Demolition Group (n = 443), % or Mean Score | Housing Improvement Group (n = 315), % or Mean Score | Control vs Demolition Group, P | Control vs Housing Improvement Group, P |

| Gender | .017 | .94 | |||

| Male | 34.63 | 43.57 | 34.92 | ||

| Female | 65.37 | 56.43 | 65.08 | ||

| Building type | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| House | 27.92 | 0.90 | 16.19 | ||

| Low-rise apartment building | 59.72 | 9.71 | 41.27 | ||

| High-rise apartment building | 12.37 | 89.39 | 42.54 | ||

| Age, y | <.001 | .946 | |||

| < 26 | 19.93 | 43.51 | 21.02 | ||

| 26–64 | 43.06 | 36.45 | 42.68 | ||

| > 64 | 37.01 | 20.05 | 36.31 | ||

| Country of birth | <.001 | .27 | |||

| United Kingdom | 94.35 | 59.14 | 92.06 | ||

| Elsewhere | 5.65 | 40.86 | 7.94 | ||

| Educational qualifications | .007 | .251 | |||

| Yes | 20.14 | 12.64 | 16.51 | ||

| No | 79.86 | 87.36 | 83.49 | ||

| Housing status | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Owner occupied | 31.80 | 5.64 | 18.73 | ||

| Rented | 68.20 | 94.36 | 81.27 | ||

| Household type | <.001 | .472 | |||

| No children | 77.74 | 56.43 | 75.24 | ||

| Children | 22.26 | 43.57 | 24.76 | ||

| Health scorea | |||||

| Mental | 47.77 | 47.87 | 47.97 | .894 | .814 |

| Physical | 46.75 | 48.58 | 45.98 | .025 | .379 |

Note. Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding.

aDerived from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey version 2; the range is 0–100, with higher scores indicating better health.

Table 2 shows SF-12v2 mean scores at each wave. By wave 2, the mean mental health score for the control group had worsened, falling by 0.84 from baseline. By contrast, mean mental health scores had increased at wave 2 by 1.15 for the demolition group and 1.26 for the housing improvement group. Physical health mean scores were lower at wave 2 than at baseline in the control (−2.86 points), demolition (−2.81 points), and housing improvement (−3.47 points) groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Adjusted Multiple Regression Results for Mental and Physical Health Scores Among Residents of Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Undergoing Demolition or Housing Improvement and Control Group: GoWell Surveys, 2006–2008

| Study Group | Wave 1, Mean Score | Wave 2, Mean Score | b (SE) | 95% CI | P |

| Mental health | |||||

| Control | 47.77 | 46.93 | 0.00 | ||

| Demolition | 47.87 | 49.03 | 2.49 (1.83) | −1.25, 6.23 | .185 |

| Housing improvement | 47.97 | 49.22 | 2.41 (1.17) | 0.03, 4.80 | .047 |

| Physical health | |||||

| Control | 46.75 | 43.89 | 0.00 | ||

| Demolition | 48.58 | 45.77 | −0.24 (1.33) | −2.96, 2.48 | .859 |

| Housing improvement | 45.98 | 42.51 | −0.66 (0.94) | −2.57, 1.25 | .486 |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Scores derived from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey version 2; the range is 0–100, with higher scores indicating better health. Physical and mental health scores were analyzed separately for 1033 complete responses. In both models, we adjusted for the corresponding baseline mean score, gender, age, education, household structure, housing status, building type, and country of birth.

Table 2 also presents our main findings from regression analyses with wave 2 SF-12v2 mean scores as dependent variables adjusted for wave 1 SF-12v2 scores, gender, building type, age, country of birth, education, housing status, and household type. For the demolition group, neither mental nor physical SF-12v2 mean scores changed significantly relative to the control group (mental health, b = 2.49; 95% CI = −1.25, 6.23; P = .185; physical health, b = −0.24; 95% CI = −2.96, 2.48; P = .859). For the housing improvement group, we found evidence of a small improvement in mean mental health scores but little change in physical health scores relative to the control group (mental health, b = 2.41; 95% CI = 0.03, 4.80; P = .047; physical health, b = −0.66; 95% CI = −2.57, 1.25; P = .486).

Tests revealed little evidence of interactions between main effects and most participant characteristics. However, we found a significant interaction (P = .02) for education and housing improvement. In the control group, SF-12v2 mental health mean scores fell between waves by 1.34 for residents with educational qualifications (n = 57) and by 0.71 for residents without qualifications (n = 226). However, in the housing improvement group, mean mental health scores fell by 4.56 for residents with qualifications (n = 52) but improved by 2.39 for unqualified residents (n = 263). Education also interacted (P = .04) with demolition group participants’ self-reported physical health: SF-12v2 physical health mean scores decreased by 3.12 for unqualified demolition group residents (n = 387), but only decreased by 0.72 for those with qualifications (n = 55). In the control group, physical health scores fell by 2.72 among unqualified and 3.39 among qualified participants.

Table 3 summarizes findings from SF-12v2 subscale analysis. We found little evidence of an intervention effect on the physical health, vitality, and role emotional subscales. However, we found an improvement in social-functioning scores for both the housing improvement group (b = 3.36; 95% CI = 0.58, 6.13; P = .019) and the demolition group (b = 4.76; 95% CI = 0.17, 9.35; P = .042). Mental health subscale scores also rose for the housing improvement group (b = 2.23; 95% CI = 0.64, 3.81; P = .007).

TABLE 3—

Adjusted Multiple Regression Subscale Results for Mental and Physical Health Scores Among Residents of Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Undergoing Demolition or Housing Improvement at Wave 2: GoWell Survey, 2006–2008

| Subscale | b (SE) | P | 95% CI |

| Physical functioning | |||

| Demolition group | −0.21 (1.44) | .883 | −3.15, 2.72 |

| Housing improvement | 0.02 (1.02) | .986 | −2.06, 2.10 |

| Role physical | |||

| Demolition | 0.60 (1.30) | .649 | −2.05, 3.24 |

| Housing improvement | 0.31 (0.70) | .664 | −1.11, 1.73 |

| Bodily pain | |||

| Demolition | −0.28 (1.82) | .88 | −3.98, 3.43 |

| Housing improvement | 0.07 (0.93) | .944 | −1.82, 1.95 |

| General health | |||

| Demolition | 2.42 (1.97) | .228 | −1.59, 6.44 |

| Housing improvement | −0.62 (0.89) | .495 | −2.44, 1.21 |

| Vitality | |||

| Demolition | −2.24 (1.45) | .134 | −5.20, 0.72 |

| Housing improvement | 0.12 (1.17) | .917 | −2.26, 2.51 |

| Role emotional | |||

| Demolition | 2.17 (1.97) | .279 | −1.85, 6.20 |

| Housing improvement | 0.94 (1.35) | .49 | −1.81, 3.70 |

| Social functioning | |||

| Demolition | 4.76 (2.25) | .042 | 0.17, 9.35 |

| Housing improvement | 3.36 (1.36) | .019 | 0.58, 6.13 |

| Mental health | |||

| Demolition | 1.84 (1.66) | .276 | −1.54, 5.21 |

| Housing improvement | 2.23 (0.78) | .007 | 0.64, 3.81 |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Scores derived from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey version 2; the range is 0–100, with higher scores indicating better health. Subscale scores were analyzed separately for 1033 complete responses. In both models we adjusted for the corresponding baseline mean score, gender, age, education, household structure, housing status, building type, and country of birth. For each variable, the control group was the reference group (b = 0.00).

DISCUSSION

We used record linkage to identify a nested longitudinal cohort from 2 cross-sectional surveys of householders experiencing different types of urban renewal in Glasgow. Our findings did not substantiate our hypothesis that continued residence in a neighborhood undergoing clearance and demolition would adversely affect residents’ health. We detected a borderline significant improvement in SF-12v2 mental health scores following housing improvement, relative to the control group, lending support to our hypothesis that home improvements would benefit residents’ health. The wide confidence intervals led us to conclude that housing improvement had either no benefit or, more probably, a small benefit to residents’ mean mental health in the short term. Improvements in social-functioning and mental health SF-12v2 subscales appeared to underpin this main effect. We found no evidence of intervention effects on self-reported physical health.

We evaluated 2 distinct types of urban renewal. By identifying a controlled longitudinal sample from a repeat cross-sectional survey, we added value to the original surveys and developed a study design better suited to exploring intervention attribution as part of a natural experiment evaluation. Natural experiments have been described as underused tools in public health research,51 and our approach may be of interest to researchers in this field. We know of no other quasi-experimental study that focuses on the effects of living in neighborhoods undergoing negative changes associated with clearance and demolition. Therefore, despite methodological limitations, ours may be the best available evidence on this issue to date.

Limitations

Recent guidance on natural experiments states that “single studies are unlikely to be definitive and replication is needed to build up confidence in conclusions about effectiveness.”44(p22) We had no influence on intervention planning, delivery, or allocation. Blinding was also impossible. The 2 interventions we investigated overlapped, with a minority of residents in demolition neighborhoods receiving limited housing improvements. The interventions were not neatly contained in a certain period, and residents of all our study areas could have been exposed to urban renewal initiatives prior to our study. Intervention exposure was not equally administered: for example, the implementation of clearance and demolition plans varied between and within neighborhoods during the study period.

The response rates to the original surveys were approximately 50%, which we consider respectable for a study of such disadvantaged neighborhoods, but selection bias was an inherent risk. We assume that selective loss to follow-up occurred, but the process of matching from 2 randomly sampled cross-sectional surveys to create the longitudinal sample made this problem difficult to quantify (Appendix C, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). The complex and pragmatic decision process that determined whether participants received an intervention during the study period was not equivalent to randomly allocating participants to study groups. Groups had physical and demographic differences—especially the demolition and control groups—which also imposed a risk of selection bias. We adjusted for known potential confounders but would need an alternative study design (e.g., involving random allocation) to address unknown or unmeasured confounding factors.44 Most outcome data were self-reported, carrying a risk of bias from common methods variance.52

We conducted interaction tests post hoc, and so the findings that less educated residents appeared to benefit most from housing improvement but were less well protected against potential harms from the demolition process must be treated with caution. Future research should test these findings more rigorously.

Implications for Research

We support the recent natural experiment guidance that emphasizes the need to replicate studies like ours to build confidence in findings and better understand their transferability. To date, the best available evidence to support hypothesized health benefits of housing improvement comes from studies of interventions that target homes with specific health risks. Hence, a recent systematic review concluded that the “potential for health benefits [from housing improvement] may depend on baseline housing conditions and careful targeting of the intervention.”21(pS681) The improvement work in our study was targeted to a degree, in that homes were managed by RSLs, located in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and assessed as in need of intervention. However, improvements were designed to meet a generally applied housing quality standard rather than to target dwellings with specific health-related problems. Thus our findings suggest that less targeted, population-level housing improvement programs may also benefit mental health in the short term. Further research into the public health impacts of less targeted mass housing improvement initiatives would therefore be welcome.

Further experimental research into the health impacts of living through demolition could help improve our understanding of the causal relationship between health and place. If neighborhood environments can rapidly deteriorate without substantially affecting residents’ health, this raises questions about assumed causal pathways. Future research could also explore speculative explanations of our findings, including hypotheses that (1) harmful neighborhood effects may have been a problem prior to 2006, potentially lessening the negative impact of the demolition programs; (2) some residents may have viewed the clearance and demolition programs positively (previous GoWell research suggests that a majority of remainers supported demolition48); (3) the interventions could have been delivered in ways that helped reduce potential negative impacts on residents; and (4) the remainer group may be more resilient than residents who relocated in the early phase of clearance.

The complexities of urban renewal are such that a thorough evaluation must address a wide range of research questions.19,41,53–59 Research into contexts, processes, mediating factors, and subgroup analysis could help us build a plausible explanation for our findings and determine whether the outcomes were socially patterned. Studies with long-term outcomes, more comparable controls, and intention-to-treat designs would also improve the evidence base.36 An exploration of how residents perceive renewal to affect their relative social position could also shed light on potential mechanisms for achieving health benefits.57,60

Conclusions

Health is not the only justification for improved housing and neighborhood renewal (e.g., renewal may have social justice or economic objectives).61 However, the question of whether urban renewal leads to negative or positive health outcomes is still highly relevant to decision-makers.19 Our findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that improving housing can also improve health, although effect sizes may be modest. Our findings on the experience of residents living through demolition and clearance are unexpected and suggest a need to critically examine the destruction-of-community argument that is sometimes made by researchers and the media in opposition to large-scale demolition programs.38,39,53

Further research is required to address outstanding issues and explore the generalizability of our findings. However, the overall implications of our results are that concerns about negative health outcomes should not be a barrier to implementing interventions of the kind we evaluated and that the possibility of modest health benefits to disadvantaged populations could be one incentive for continued investment in large-scale urban renewal.

Acknowledgments

GoWell is funded by the Scottish Government, NHS (National Health Service) Health Scotland, Glasgow Housing Association, Glasgow Centre for Population Health, and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Matt Egan, Martins Kalacs, Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi, and Lyndal Bond were funded by the Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorate, as part of the Evaluating Social Interventions program at the MRC Social and Public Health Science Unit (5TK40). Ade Kearns was funded by the University of Glasgow. Carol Tannahill was funded by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. The surveys were conducted by BMG Research.

We thank Sally Macintyre and Martin John McKee.

Human Participant Protection

The NHS Scotland multicentre research ethics committee approved the study.

References

- 1.Clark C, Myron R, Stansfeld S, Candy B. A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health. J Public Ment Health. 2007;6(2):14–27 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen IH, Michael YL, Perdue L. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):455–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croucher K, Myers L, Jones R, Ellaway A, Beck S. Health and the Physical Characteristics of Urban Neighbourhoods: A Critical Literature Review. Glasgow, UK: Glasgow Centre for Population Health; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison KK, Lawson CL. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truong KD, Ma S. A systematic review of relations between neighborhoods and mental health. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2006;9(3):137–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renalds A, Smith TH, Hale PJ. A systematic review of built environment and health. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(1):68–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egan M, Tannahill C, Petticrew M, Thomas S. Psychosocial risk factors in home and community settings and their associations with population health and health inequalities: a systematic meta-review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh A, Gordon D, Heslop P, Pantazis C. Housing deprivation and health: a longitudinal analysis. Housing Stud. 2000;15(3):411–428 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellaway A, Benzeval M, Green M, Leyland A, Macintyre S. “Getting sicker quicker”: does living in a more deprived neighbourhood mean your health deteriorates faster? Health Place. 2012;18()2:132–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giskes K, Van Lenthe FJ, Turrell G, Brug J, Mackenbach JP. Smokers living in deprived areas are less likely to quit: a longitudinal follow-up. Tob Control. 2006;15(6):485–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haan M, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health. Prospective evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(6):989–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford M, Gimeno D, Marmot MG. Neighbourhood characteristics and trajectories of health functioning: a multilevel prospective analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(6):604–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Poverty area residence and changes in physical activity level: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1709–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Poverty area residence and changes in depression and perceived health status: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(1):90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruel E, Reither EN, Robert SA, Lantz PM. Neighborhood effects on BMI trends: examining BMI trajectories for Black and White women. Health Place. 2010;16(2):191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stafford M, Brunner EJ, Head J, Ross NA. Deprivation and the development of obesity. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(2):130–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean J. Glasgow’s Deprived Neighbourhood Environments and Health Behaviours—What Do We Know? GoWell Briefing Paper. Glasgow, UK: Glasgow Centre for Population Health; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Propper C, Burgess S, Bolster A, Leckie G, Jones K, Johnston R. The impact of neighbourhood on the income and mental health of British social renters. Urban Stud. 2007;44(2):393–415 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearns A, Tannahill C, Bond L. Regeneration and health: conceptualising the connections. J Urban Regen Renewal. 2009;3(1):56–76 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commission on Social Determinants of Health Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. The health impacts of housing improvement: a systematic review of intervention studies from 1887 to 2007. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 3):S681–S692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkinson R, Thomson H, Kearns A, Petticrew M. Giving urban policy its ‘medical’: assessing the place of health in area-based regeneration. Policy Polit. 2006;34(1):5–26 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD008657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs DE, Brown MJ, Baeder Aet al. A systematic review of housing interventions and health: introduction, methods, and summary findings. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5 suppl):S5–S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger J, Jacobs DE, Ashley PJet al. Housing interventions and control of asthma-related indoor biologic agents: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5 suppl):S11–S20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandel M, Baeder A, Bradman Aet al. Housing interventions and control of health-related chemical agents: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5 suppl):S24–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiGuiseppi C, Jacobs DE, Phelan KJ, Mickalide AD, Ormandy D. Housing interventions and control of injury-related structural deficiencies: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5 suppl):S34–S43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindberg RA, Shenassa ED, Acevedo-Garcia D, Popkin SJ, Villaveces A, Morley RL. Housing interventions at the neighborhood level and health: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5 suppl):S44–S52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackman T, Harvey J. Housing renewal and mental health: a case study. J Ment Health. 2001;10(5):571–583 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howden-Chapman P, Pierse N, Nicholls Set al. Effects of improved home heating on asthma in community dwelling children: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barton A, Basham M, Foy C, Buckingham K, Somerville M, Torbay Healthy Housing Group The Watcombe Housing Study: the short term effect of improving housing conditions on the health of residents. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(9):771–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howden-Chapman P, Matheson A, Crane Jet al. Effect of insulating existing houses on health inequality: cluster randomised study in the community. BMJ. 2007;334(7591):460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batty E, Beatty C, Foden F, Lawless P, Pearson S, Wilson I. The New Deal for Communities Experience: A Final Assessment. Vol. 7 London, UK: CLG; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson H, Atkinson R, Petticrew M, Kearns A. Do urban regeneration programmes improve public health and reduce health inequalities? A synthesis of the evidence from UK policy and practice (1980–2004). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):108–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huxley P, Evans S, Leese Met al. Urban regeneration and mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(4):280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LAet al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337(6101):1505–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popkin S, Levy D. Hope VI Panel Study Baseline Report. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fullilove MT. Root Shock, How Tearing Up City Neighhorhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. New York, NY: One World/Ballantine; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paris C, Blackaby B. Not Much Improvement: Urban Renewal Policy in Birmingham. London, UK: Heinemann; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kearns A, Mason P. Defining and measuring displacement: is relocation from restructured neighbourhoods always unwelcome and disruptive? Housing Stud. Epub ahead of print, February 18, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawson L, Egan M. Residents’ Lived Realities of Transformational Regeneration. Glasgow, UK: GoWell; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egan M, Kearns A, Mason Pet al. Protocol for a mixed methods study investigating the impact of investment in housing, regeneration and neighbourhood renewal on the health and wellbeing of residents: the GoWell programme. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10(41). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre Set al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Craig P, Cooper C, Gunnell Det al. Using Natural Experiments to Evaluate Population Health Interventions. Glasgow, UK: Medical Research Council; 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selection, Definition and Description of Study Areas. GoWell Working Papers. Glasgow, UK: GoWell; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh D. Health and Wellbeing in Glasgow and the GoWell Areas—Deprivation Based Analyses. Glasgow, UK: GoWell; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scottish Housing Quality Standard Progress Report. Edinburgh, UK: Communities Scotland; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Progress for People and Places: Monitoring Change in Glasgow’s Communities. Evidence From the GoWell Surveys 2006 and 2008. Glasgow, UK: GoWell; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware JE, Koninski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. How to Score Version Two of the SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stata Release 9 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petticrew M, Cummins S, Ferrell Cet al. Natural experiments: an underused tool for public health? Public Health. 2005;119(9):751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doty DH, Glick WH. Common methods bias: does common methods variance really bias results? Organ Res Methods. 1998;1(4):374–406 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beck SA, Hanlon PW, Tannahill CE, Crawford FA, Ogilvie RM, Kearns AJ. How will area regeneration impact on health? Learning from the GoWell study. Public Health. 2010;124(3):125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kearns A, Lawson L. (De)constructing a policy “failure”: housing stock transfer in Glasgow. Evid Policy. 2009;5(4):449–470 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawson L, Kearns A. 'Community empowerment' in the context of the Glasgow housing stock transfer. Urban Stud. 2010;47(7):1459–1478 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lawson L, Kearns A. Community engagement in regeneration: are we getting the point? J Hous Built Environ. 2010;25(1):19–36 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kearns A, Whitley E, Bond L, Egan M, Tannahill C. The psychosocial pathway to mental well-being at the local level: investigating the effects of perceived relative position in a deprived area context. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(1):87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bond L, Kearns A, Mason P, Tannahill C, Egan M, Whitely E. Exploring the relationships between housing, neighbourhoods and mental wellbeing for residents of deprived areas. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Egan M, Lawson L. Residents' Perspectives of Health and Its Social Contexts. Glasgow, UK: GoWell; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deaton A. Relative Deprivation, Inequality, and Mortality. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2001. NBER Working Paper 8099 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomson H. A dose of realism for healthy urban policy: lessons from area-based initiatives in the UK. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(10):932–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]