Abstract

Despite the HIV “test-and-treat” strategy’s promise, questions about its clinical rationale, operational feasibility, and ethical appropriateness have led to vigorous debate in the global HIV community.

We performed a systematic review of the literature published between January 2009 and May 2012 using PubMed, SCOPUS, Global Health, Web of Science, BIOSIS, Cochrane CENTRAL, EBSCO Africa-Wide Information, and EBSCO CINAHL Plus databases to summarize clinical uncertainties, health service challenges, and ethical complexities that may affect the test-and-treat strategy’s success.

A thoughtful approach to research and implementation to address clinical and health service questions and meaningful community engagement regarding ethical complexities may bring us closer to safe, feasible, and effective test-and-treat implementation.

ALTHOUGH WE HAVE SEEN significant progress in expanding HIV prevention and care services worldwide, an estimated 2.5 million individuals were newly infected in 2011.1 Universal testing and treatment to prevent transmission of HIV has gained considerable interest from funders and international agencies as a potential public health approach to controlling the spread of the epidemic.2,3 In a “test-and-treat” strategy, individuals would be routinely tested for HIV, and those who are identified as being HIV infected would be started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) immediately, irrespective of their stage of disease, to reduce their plasma viral load and thereby reduce their likelihood of transmitting the infection. Data from the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 trial, which demonstrated a 96% reduction in transmission in HIV infection among serodiscordant couples treated immediately compared with those receiving deferred treatment, provided the needed scientific “proof of concept” for test-and-treat programs as an effective method of reducing HIV transmission.4 At the population level, in San Francisco, California, and Vancouver, Canada, new diagnoses of HIV and community viral loads declined in the years following expanded ART.5–7 The mathematical modeling of Granich et al. at the World Health Organization in 2009 suggested that a universal voluntary test-and-treat strategy could virtually eliminate new HIV infections in South Africa within 10 years of its inception.8

Despite the test-and-treat strategy’s promise, unanswered questions about its clinical rationale, operational feasibility, and ethical appropriateness have led to vigorous debate in the global HIV community. We performed a systematic review of the scientific literature to identify the clinical uncertainties, health service challenges, and ethical complexities that may impede the success of a test-and-treat strategy. On the basis of our review, we have summarized uncertainties, challenges, and complexities we identified in the literature, and we have made research and implementation recommendations that should be considered to improve the likelihood of the test-and-treat strategy’s success.

METHODS

In May 2012, we searched the PubMed, SCOPUS, Global Health, Web of Science, BIOSIS, Cochrane CENTRAL, EBSCO Africa-Wide Information, and EBSCO CINAHL Plus databases for all articles pertaining to the HIV test-and-treat strategy. We used the following search term structure: (“test and treat” OR “universal testing” OR “universal treatment” OR “treatment as prevention”) AND (“HIV” [MeSH term] OR “HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” [MeSH terms]). We included the MeSH terms in the search only in the PubMed database. We identified all such articles published beginning January 2009 through May 2012. We chose January 2009 as the starting point for article identification because that was the month and year in which Granich et al. at the World Health Organization published their seminal and widely acclaimed mathematical model that brought the HIV test-and-treat concept to international attention. A PRISMA9 statement for the full protocol was created and registered in the PROSPERO database, with registration number CRD42012002883.10

Article Selection

Two reviewers independently reviewed article abstracts and recommended them for full-length article review if the abstract subject pertained to HIV infection and met 1 of the following conditions: (1) mentioned “test-and-treat,” “seek, test, and treat,” “treatment as prevention,” “universal testing and treatment,” or “universal access to treatment”; (2) mentioned how the particular study’s findings have implications for the widespread implementation of HIV testing and immediate initiation of ART or the widespread use of ART as prevention; or (3) mentioned concerns or gaps in the evidence on the widespread implementation of HIV testing and immediate initiation of ART or the widespread use of ART as prevention.

We excluded articles if they were book chapters, were conference abstracts, had no listed author, or were not available in English. We excluded articles focusing solely on the use of antiretroviral (ARV) medications for preexposure prophylaxis, postexposure prophylaxis, or mother to child transmission to reduce HIV transmission or incidence as well as articles whose main outcome was something other than HIV transmission and incidence, such as tuberculosis incidence. When abstracts were not available or reviewers disagreed about whether the article met inclusion criteria, we referred the article for full article review. We again reviewed articles accepted for full-length review to determine whether they met the described criteria. We resolved differences between reviewers regarding whether an article met criteria by consensus after reference to the original article.

Data Collection Process

Two reviewers read full articles that met inclusion criteria and categorized them by study design into the following categories: empirical results from an experimental design, observational study, or mathematical modeling analysis; narrative or systematic review article; or commentary, including correspondences. Review articles included both systematic reviews and narrative reviews. We distinguished narrative reviews from commentaries by their aim to substantially review literature and evidence that identified critical points of the current knowledge on particular topics related to test and treat. Commentaries, which included short pieces and correspondences, included substantial argumentative points but did not attempt to summarize the literature on the topic of interest.

Reviewers also identified any comment in an article of clinical uncertainty, health service challenge, or ethical complexity that may impede the success of the test-and-treat strategy. The authorship team developed an a priori list of clinical, health service, and ethical themes to further describe each clinical, health service, or ethical comment in question. Reviewers labeled each identified comment with 1 of the themes. Reviewers also added themes to the list if the original a priori theme list did not adequately describe the uncertainty, challenge, or complexity in question. One reviewer combined both reviewers’ lists of thematically categorized comments into a single final list. The final list included the a priori list of themes along with all reviewer-generated themes. To identify and describe as many comments as possible, if only 1 of the reviewers noted a particular comment in a given article, we still included the comment and tallied it in the final list.

RESULTS

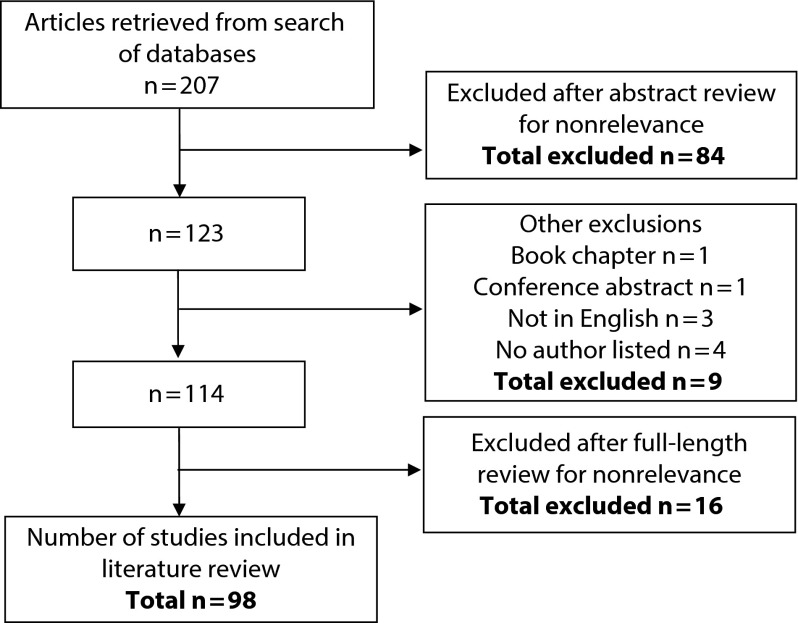

On the basis of our search strategy, we identified 207 articles (Figure 1). Of the 207 abstracts we reviewed, we excluded 84 because they were not relevant to the subject of review by our preset abstract review criteria. Of the remaining 123 citations we reviewed for inclusion, 1 was a book chapter, 1 was a conference abstract, 3 were not in English, and 4 had no author listed. Of the 114 full-length articles we reviewed, we excluded 16 on the basis of full-length article review criteria. Of the final 98 articles we selected for full-length review, 53 (54%) were commentaries, 28 (29%) were review articles, 11 (11%) were observational studies, and 6 (6%) were modeling studies (Table 1).11–108 No studies contained empirical results derived from an experimental design.

FIGURE 1—

Summary of systematic review article selection process.

TABLE 1—

Systematic Review Article Type by Frequency: January 2009–May 2012

| Study Type | Articles (n = 98), No. (%) |

| Empirical study | |

| Experimental design | 0 |

| Observational design | 11 (11) |

| Modeling | 6 (6) |

| Review article | 28 (29) |

| Commentary | 53 (54) |

The most frequently noted clinical theme was that published test-and-treat models showing the potential for HIV elimination, the Granich model in particular, are derived from uncertain or unrealistic assumptions (n = 27; Table 2). Many articles noted the concern that the test-and-treat strategy may lead to increased risk-taking behaviors among HIV-positive individuals who are on ART, thereby reducing the effect that early treatment would have on preventing secondary HIV transmission (n = 25). Another commonly noted uncertainty was related to the potentially significant role that acute HIV infection may play in the dynamics of HIV transmission at a population level (n = 20). The success of test and treat in appreciably reducing HIV incidence may depend on being able to identify acute HIV infection in a timely manner, a capability that is not feasible in most high-prevalence and resource-limited settings. Several mentioned the current lack of definitive evidence of early ART initiation’s benefit in individuals at the earliest stages of the disease as well as uncertainties related to potential long-term toxicities of ARVs (n = 20). ARV resistance was commonly noted as both a potential unintended consequence of expanded treatment and a factor that could eventually impede the ability of individuals to achieve viral suppression and therefore prevent transmission (n = 19). Nine articles noted that there is no evidence to date that early ART initiation results in reduced HIV transmission in couples or populations over long periods.

TABLE 2—

Themes of Uncertainties, Challenges, and Complexities by Frequency: January 2009–May 2012.

| Theme | No. | References |

| Clinical uncertainties | ||

| Unrealistic mathematical modeling assumptions | 27 | 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 36, 39, 41, 45, 53, 56, 60, 61, 67, 68, 69, 70, 79, 87, 95, 96, 97, 100, 102, 104, 105 |

| Increased risk behaviors when receiving ART | 25 | 3, 11, 20, 24, 31, 33, 53, 55, 57, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 75, 87, 91, 92, 97, 102, 104, 106 |

| Acute HIV and role in transmission | 20 | 3, 11, 23, 31, 33, 50, 57, 60, 64, 70, 71, 74, 90, 93, 94, 95, 97, 104 |

| Benefits and risks of early initiation of ART | 20 | 3, 16, 20, 24, 28, 29, 38, 39, 48, 50, 51, 53, 56, 57, 60, 61, 67, 72, 98, 102 |

| ARV resistance | 19 | 3, 20, 28, 29, 31, 33, 51, 53, 55, 57, 61, 71, 73, 87, 95, 97, 99, 100, 106 |

| Durability of decreased transmission long term | 9 | 20, 29, 32, 43, 51, 63, 71, 73, 100 |

| Residual genital tract viral secretion | 9 | 20, 28, 31, 53, 56, 64, 65, 66, 95 |

| Role of concurrent sexually transmitted infections | 8 | 31, 53, 63, 64, 65, 66, 87, 102 |

| Penile–anal transmission | 6 | 37, 43, 46, 56, 104, 105 |

| Detecting treatment failure in resource-limited settings | 6 | 35, 55, 71, 79, 103, 104 |

| Health service challenges | ||

| Optimizing linkage and retention rates | 30 | 3, 11, 14, 16, 19, 20, 24, 34, 37, 39, 43, 46, 51, 53, 56, 58, 60, 61, 67, 68, 87, 88, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 104 |

| Optimizing HIV testing strategies | 30 | 11, 13, 14, 16, 19, 20, 22, 24, 25, 34, 37, 43, 45, 46, 51, 52, 53, 60, 70, 71, 72, 74, 82, 83, 87, 96, 97, 98, 101, 104 |

| Optimizing adherence to ART | 23 | 6, 14, 20, 43, 45, 53, 56, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 68, 71, 74, 75, 96, 98, 99, 100, 101, 104 |

| Overcoming social and structural barriers | 22 | 15, 21, 34, 37, 43, 48, 52, 53, 56, 57, 60, 61, 67, 68, 74, 77, 79, 80, 89, 99, 102, 106 |

| Drug and program implementation costs | 22 | 11, 20, 39, 46, 51, 53, 56, 57, 60, 61, 64, 67, 68, 74, 77, 79, 80, 87, 95, 97, 99, 102 |

| Drug supply and second-line drug availability | 9 | 23, 53, 61, 64, 74, 77, 79, 99, 103 |

| Health care workforces issues | 9 | 53, 57, 61, 70, 73, 79, 83, 102, 103 |

| Ethical complexities | ||

| Resource allocation with scarce resources | 22 | 3, 11, 15, 17, 23, 32, 41, 42, 44, 46, 48, 53, 60, 67, 68, 71, 74, 79, 94, 97, 99, 102 |

| Balancing individual vs societal benefit | 13 | 3, 15, 20, 23, 33, 42, 46, 49, 52, 71, 79, 99, 104 |

| Coercion and informed consent | 12 | 6, 15, 20, 32, 33, 40, 46, 53, 61, 84, 101, 102 |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; ARV = antiretroviral.

Other, less commonly noted themes included evidence gaps concerning whether individuals who have undetectable plasma viral loads may in some scenarios continue to shed HIV in their genital tract and therefore potentially be infectious (n = 9); concerns about how unrecognized concurrent sexually transmitted infections can increase likelihood of HIV transmission and therefore potentially reduce the effectiveness of test and treat (n = 9); lack of evidence demonstrating effectiveness of early ART treatment in reducing transmission in populations of men who have sex with men or other populations with high levels of penile–anal sexual intercourse (n = 6); and concerns about how limited access to technologies to detect treatment failure in resource-limited settings may affect the ability of individuals in test-and-treat programs to achieve viral suppression (n = 6).

The vast majority of health service challenges noted in our review centered on the argument that without optimal linkage and retention (n = 30), optimal HIV testing strategies (n = 30), and adherence programs (n = 23) to ensure that HIV-infected individuals are identified, initiated, and retained in care and that they achieve viral load suppression, the test-and-treat strategy will not result in significant reductions in HIV incidence. Social and structural barriers, such as poverty, incarceration, substance abuse, and stigma, were also noted to be challenges to the implementation of the test-and-treat strategy in marginalized populations (n = 22). Drug and program implementation costs associated with widespread testing and treatment were commonly noted as a likely barrier to implementation (n = 22). Other challenges included capacity issues such as the current inadequacy of the health care workforce (n = 9) and drug supply systems (n = 9) in many of the most affected countries, which could impede timely availability of medical care and first- and second-line therapies.

The majority of the ethical complexities we identified centered on resource allocation issues (n = 22): the potential for the test-and-treat strategy to divert resources from other forms of HIV prevention, such as syringe exchange programs; from treatment of those who may need it most; and from other diseases or conditions. Another ethical complexity pertained to the tension that might arise as part of a test-and-treat strategy between an individual’s health benefit or treatment desires concerning ART and the public health benefit of reduced transmission from ART (n = 13). Finally, several articles included a concern that test-and-treat programs may be perceived or inadvertently carried out in such a way that individuals experience coercion or cannot exert proper informed consent (n = 12).

DISCUSSION

Our review of the HIV test-and-treat literature revealed numerous uncertainties, challenges, and complexities across the dimensions of clinical science, health services delivery, and ethics. Not surprisingly, considering the recent nascence of the test-and-treat strategy as a concept, fewer than 1 in 5 articles contained empirical data. Commentaries, which accounted for half of the articles, reflected the perspectives of experts and leaders in the fields of HIV treatment and prevention. On the basis of the findings of the literature review, we have proposed a strategic and thoughtful approach to research, implementation, and community engagement that will address the outstanding questions about and challenges to the test-and-treat strategy.

Clinical Uncertainties

One of the most critical questions concerning test and treat is whether the long-term benefit of early ART initiation to decrease HIV transmission outweighs the potential risks to the individual of long-term, lifelong treatment, such as drug toxicities and earlier treatment failure. Several ongoing studies will help answer some of the clinical uncertainties identified in this review (Table 3). The Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment trial and HPTN052 study will provide solid data in the next few years on the health outcomes for individuals receiving early versus delayed treatment.107,108 The British Columbia population-based study Seek and Treat to Optimally Prevent HIV and AIDS will provide much needed data about the impact that expanded ART availability has on population HIV incidence.109,110

TABLE 3—

Ongoing Test and Treat Research Studies: January 2009–May 2012

| Study Name | Study Type | Pertinent Research Objectives and Findings | Timeframe |

| Population Effect of ART to Reduce HIV Transmission | Phase I: mixed methods study of feasibility and acceptability of comprehensive testing program in rural (Masaka, Uganda) and urban (Kabwe, Zambia) locations; pilot of immediate ART initiation to 100 newly diagnosed HIV patients | Examine uptake of test and treat, community engagement to enhance acceptability and human rights concerns, cost-effectiveness to inform design of cluster RCT; for pilot patients, examine adherence, viral load, CD4, OI, and drug resistance for 1 year after initiation; community HIV incidence | Phase I: 2010–2013 Phase II: 2013– |

| Phase II: cluster-randomized trial of impact of treatment of all HIV-infected individuals | |||

| Treatment as Prevention | Phase 0: feasibility of providing universal testing and universal ART in South Africa | Examine best approaches to universal testing and universal ART to inform the design of cluster RCT; examine impact of ART on population HIV incidence, ARV resistance, HIV morbidity, adherence, adverse events, and high-risk behaviors and determine origin of new infections; examine population effectiveness and sustainability | Phase I: 2009–2011 Phase II: 2011–2015 Phase II: 2015– |

| Phase I: cluster-randomized trial of impact of treatment of all HIV-infected individuals | |||

| Phase II: expansion phase | |||

| National Institute of Mental Health Project Accept (NCT00203749) | Phase III: randomized control trial of community mobilization, mobile testing, same-day results, and posttest support for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand | Examine efficacy of Community-Based HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing (CBVCT) intervention plus standard clinic-based VCT (SVCT) or SVCT alone; CBVCT more effective than is SVCT in increased detection of HIV infection, especially in regions with restricted access to clinic-based VCT and support services after testing | Study completed in August 2011 |

| Effectiveness of ART plus HIV Primary Care versus Primary Care Alone to Prevent Sexual Transmission of HIV-1 in Serodiscordant Couples (HPTN052) | Phase III: 2-arm, randomized control, multicenter trial of early ART in 1750 discordant couples in 8 countries | Measure impact of 2 treatment initiation thresholds; first arm initiated on enrollment, second arm initiated at CD4 ≤ 250 cells/mm3, on disease transmission, HIV progression, and ART toxicity; dramatic 96% reduction in HIV transmission in couples with early treatment announced in May 2011 | Deferred treatment arm discontinued May 2011; data collection on secondary endpoints will continue through 2013 |

| TLC-Plus: Feasibility of an Enhanced Test, Link to Care, Plus Treat Approach for HIV Prevention in US | Feasibility and effectiveness study of test and treat and strengthened linkage programs in United States (New York City and Washington, DC) | Examine impact of 4 components of community-focused enhanced test-and-treat strategy on prompt ART initiation, viral suppression, and high-risk behaviors | Enrollment began in 2010 and is ongoing; data collection to end 2013 or 2014 |

| Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment | Randomized control trial of 4000 HIV-positive persons in 23 countries, minimum follow up 3 y | Compare immediate ART to deferred ART (CD4 ≤ 350 cells/mm3) for each component of the primary composite endpoint: AIDS, non-AIDS, or death from any cause | 2009–2015; data collection will be complete 2015 |

| Seek and Treat to Optimally Prevent HIV and AIDS | Phase III: population-based study of expanded ART availability in British Columbia, Canada | Measure impact of ART expansion on population HIV incidence at 3–5 y; secondary outcomes include AIDS morbidity and mortality, CD4 counts, viral load, drug resistance, safety, and health care utilization | 2010–2013; data collection will be complete end of 2013 |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; CD4 = cluster of differentiation 4; HPTN = HIV Prevention Trials Network; OI = opportunistic infection; RCT = randomized control trial; TLC = testing and linkage to care; VCT = voluntary counseling and testing.

Because rigorously derived data answering these questions are not anticipated for another few years, implementation efforts should first be focused on achieving universal testing and treatment according to current World Health Organization guidelines for the initiation of ART. Achieving this would be a giant step forward for the HIV epidemic in every country but particularly so in resource-limited contexts in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, successfully implementing universal treatment according to guidelines will necessarily require addressing and finding solutions for many health service–related challenges that are also major barriers to effective test-and-treat implementation.

ARV resistance from expanded treatment remains a looming uncertainty that may affect individual and population outcomes. Although recent experiences in San Francisco and Vancouver suggest that transmitted drug-resistant strains in those communities have remained stable or decreased during the period when ART use expanded significantly, some researchers have shown through modeling the high likelihood for multiple ARV-resistant strains to evolve and replace wild-type strains with test-and-treat.15,111–113 Populations starting treatment at earlier stages of infection as part of a test-and-treat strategy may have poorer adherence rates, resulting in a theoretically greater risk of resistance promulgation. At the same time, in most resource-limited settings, viral load quantification and genotype testing do not exist. To more accurately assess ARV resistance and detect treatment failures with universal treatment, many countries will require substantial investments in their health systems to build or strengthen components such as laboratory services and monitoring and evaluation systems.

Several clinical questions related to the real-world effectiveness of test-and-treat in reducing HIV transmission remain unanswered and underscore the need for ongoing research. There is emerging evidence of persistent HIV in genital secretions even when plasma levels are undetectable17,114–115; whether this is clinically relevant to HIV transmission risk is still not well understood. Similarly, more research is needed to explore the role of concurrent sexually transmitted infections on HIV transmission and ascertain whether the potential threat of increased risk disinhibition among persons receiving ART exists and affects transmission. The efficacy of test and treat for sexual encounters that are predominantly penile–anal in nature is also not explicitly known from HPTN052, because the study population included few men who have sex with men.7,43,104 Also, the contribution of the acute HIV infection stage, during which most patients are unidentified, untreated, and possibly participating in high-risk behaviors, to the maintenance and growth of the HIV epidemic is unknown and possibly very important.33,90,104 Until these questions are better understood, it will be difficult to predict how effective test-and-treat will be in practice.

Health Service Challenges

We found that many of the most pressing issues facing the test-and-treat strategy are health services or implementation challenges, such as optimizing retention and workforce capacity. It is not uncommon once biomedical prevention strategies, such as treatment as prevention, are shown to be efficacious for questions related to long-term effectiveness in real-world settings to be sidelined as implementation challenges.67 As a result, the important roles that systems, social contexts, and risk behavior play in enabling sustainable adoption of biomedical prevention interventions are inadequately acknowledged and inadequately researched, to the detriment of progress in the field.67

A prime example of this is the lack of scientific knowledge on best practices to motivate HIV-positive individuals, especially those who are asymptomatic from the disease, to become and stay engaged in regular HIV care and remain adherent to ART over long periods. The International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care recently published guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and ART adherence for persons with HIV in which it recommends systematic monitoring of entry and retention in HIV care; however, existing evidence-based interventions to guide action on these data to actually engage patients in care are sparse.116 Available interventions, such as case management and patient navigators, to help individuals who are suboptimally engaged in care or who have fallen out of care in the United States require intensive resources and may be difficult to reproduce in many parts of the world.

Community-based participatory research methods may be useful for addressing this specific health service challenge of test and treat. The National Institutes of Health defines community-based participatory research as

Scientific inquiry conducted in communities in which community members, persons affected by the condition or issue under study and other key stakeholders in the community’s health have the opportunity to be full participants in each phase of the work: conception, design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, conclusions, and communication of results.117

Community involvement in developing and studying behavioral and health system interventions to address social and structural barriers to retention and ART adherence may yield better solutions to these persistent challenges by accounting for the local cultural and social contexts in resource-limited countries.

Concerns about health care systems or health care workforce capacity to successfully absorb increased patient volumes and provide high-quality, guideline-based care were surprisingly infrequently noted, despite their importance to the success of test-and-treat programs. Implementation issues related to systems and workforce capacity may be best addressed through the use of health services and implementation science research methodologies.118,119 Two Africa-based studies, Population Effect of ART Therapy to Reduce HIV Transmission and Treatment as Prevention, and 1 US-based study, Feasibility of an Enhanced Test, Link to Care, Plus Treat Approach for HIV Prevention in US, are currently in the field and will assess feasibility, costs, and best approaches for universal testing and treatment in communities.24,110,120–122 Aside from these studies, more location-specific implementation questions will likely remain as programs are rolled out. Rapid cycle quality improvement approaches may be particularly effective, as they provide timely and locally applicable data to track performance, highlight areas for improvement, and measure the impact of changes in program design.123 Investment in and integration of performance measurement systems in the care delivery system from the beginning will be the best way to ensure that test-and-treat programs have reliable and inexpensive access to data to ensure patient safety and maximal program effectiveness.

More attention should also be paid to developing integrated and comprehensive care delivery models in resource-limited settings to replace fragmented health systems designed for specific diseases. Innovative methods, such as community mobilization, locating HIV care outside standard health care settings, and task shifting to lay workers, may also be more effective and successful models of health care delivery. Project Accept, a cluster-randomized, controlled trial of community-based voluntary counseling and testing in which community mobilization and community-based service approaches were compared with standard voluntary counseling and testing at clinical locations, demonstrated substantially greater patient testing rates and HIV case detection with community involvement.124

Lastly, sustainable funding to scale up HIV care systems and ensure lifelong treatment remains an enormous challenge at this time of global economic uncertainty. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS estimated that to achieve universal access to appropriate HIV services worldwide in accordance with current treatment guidelines, $42.2 billion—a 4-fold increase in investment from 2007 levels—would be required.1 Unfortunately, with funding in 2009 plateauing at $15.9 billion, only 36% of the 15 million people in need in low- and middle-income countries had received treatment by the beginning of 2010.28,125,126 Cost estimates for a test-and-treat strategy would certainly exceed the estimated resources needed for guideline-based therapy, at least until HIV incidence dramatically declines. In addition, costs associated with programs to improve retention and maintain the health care delivery infrastructure may not be appropriately factored into cost estimates.46,127 It seems unlikely that test-and-treat can be financed because current funding levels cannot support adequate treatment of HIV-positive individuals meeting current treatment guidelines. However, showing that the test-and-treat strategy dramatically reduces HIV incidence in real-world settings may provide the strongest case yet for funding agencies and governments to invest the necessary substantial resources to eliminate the HIV epidemic.

Ethical Concerns

Test-and-treat raises prohibitive ethical concerns in terms of balancing public health ethics and principlism (autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice), distributive justice in resource-limited settings, and concern for patient coercion. Because of existing clinical uncertainties and health service challenges, the ethical justification for the test-and-treat strategy is grounded in public health ethics and utilitarianism. This is a shift from the patient-centered principlism on which HIV care and treatment has traditionally been based.15,57,128 Public health ethics allows the use of restrictions, mandates, and quarantines when the risk to the many outweighs the personal liberties of the few. It remains unclear, however, whether the public health benefits of test-and-treat sufficiently outweigh the potential risks to the individual, particularly risks related to early initiation of ART. If there is increased risk of drug toxicity and eventual drug resistance for individuals starting ART early, the argument in favor of utilitarianism over principlism becomes more difficult to justify.52 If, as is anticipated, more evidence emerges demonstrating a safety and survival benefit to the individual from treatment at earlier stages of disease, HIV test-and-treat will no longer require a careful assessment of this ethical balancing act and may be ethically practiced with respect to both the individual and society.

In the absence of definitive data on the individual-level clinical benefits and risks and the public health benefit of reduced HIV incidence, it is difficult to ethically justify widespread implementation of test-and-treat. Even if the clinical and public health benefits are shown to outweigh the risks in research settings, effective approaches to the health service challenges related to widespread implementation demand attention. From an ethical perspective, without health systems capable of delivering test-and-treat effectively, the favorable benefit–risk ratio realized in research studies may not be achieved. Considering the enormous potential benefits of test-and-treat, it could be argued that carefully controlled implementation trials that test the effectiveness of the strategy are an ethical imperative.

Another significant ethical complexity relates to distributive justice, or the equitable allocation of resources.17 As scarce resources are employed for test-and-treat, it is conceivable that programs may provide ART to asymptomatic individuals in 1 setting, whereas elsewhere vast numbers of individuals who meet current World Health Organization guidelines for therapy would not receive treatment.71 Redistributing these scare resources also has the potential for the test-and-treat strategy to divert resources away from other forms of HIV prevention and other diseases and conditions.67

The potential for patient coercion in implementing test-and-treat also requires attention. Providers and health system staff may implicitly or explicitly feel pressured to ensure that they test or start as many patients as they can on ART at the time of diagnosis. Although proper informed consent (discussion regarding diagnosis, prognosis, risks, and benefits of early vs delayed treatment) as well as safeguards against the social stigma of HIV are still possible in such encounters, these discussions and safeguards may be inadvertently compromised by test-and-treat. This is especially true when the individual benefit of treatment may be perceived as relatively small. As pressure to perform mounts from external parties and funders, the potential for coercion will exist and is troublesome.46,53,61 The ethical implementation of test-and-treat thus requires the systematic education of providers and improvement of systems to ensure that undue pressure on providers is minimized to decrease the potential for patient coercion.

The Population Effect of ART to Reduce HIV Transmission study, which uses mixed methods to assess community engagement and acceptability and human rights concerns to inform the design of a test-and-treat trial in 2 communities in Zambia and Uganda, will help address these 3 ethical issues.23,120 The study will include qualitative research on trust, barriers, and experiences in service delivery; an assessment of 5 components related to human rights and ethics; and engagement with African partners to identify study sites, all while highlighting local issues that are key to implementing the test-and-treat strategy.23,120

Outside the context of the Population Effect of ART to Reduce HIV Transmission study, the engagement of community members and persons living with HIV/AIDS will remain critical to the acceptance and success of test-and-treat implementation. Equitable partnerships that community-based participatory research of community stakeholders, persons living with HIV/AIDS, implementers, and, when applicable, researchers enable should be pursued to ease concerns about experimentation and coercion. By engaging in community-based consensus building, many of the health service challenges and ethical complexities of test-and-treat can be more optimally addressed in local epidemic contexts.6

Community mobilization is also considered a promising strategy to address stigma related to HIV/AIDS and other social vulnerabilities affecting access to and use of HIV care.32,129,130 This is especially true in resource-poor areas to ensure that the benefits of current research endeavors being conducted there are not simply transplanted to resource-rich areas but that researchers strive to implement the results of their work in the communities supporting the research.131 Empowering local organizations through community partnership can ensure that the public health agenda and need for knowledge generation is balanced by the community’s perception of mutual benefit.132

Conclusions

Innovative modeling and recent empirical evidence suggest that the test-and-treat strategy is an important and unparalleled opportunity to address the HIV epidemic. A great deal of work related to numerous clinical uncertainties, health service challenges, and ethical complexities remains to be done. Until this work is done, implementation efforts should be focused on achieving universal testing and treatment according to current World Health Organization guidelines for the initiation of ART. A strategic and thoughtful approach to research, implementation, and community engagement to achieve guideline-based treatment will necessarily require addressing and finding solutions for many outstanding clinical, health service, and ethical concerns, bringing us closer to making the promise of test-and-treat a reality.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program (to S. P. K.); the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant GM08042 to K. V. S.); the UCLA-Caltech Medical Scientist Training Program (to K. V. S.); the Centers for AIDS Research (grant 5P30 AI028697 to A. P. M.); the UCLA AIDS Institute (to A. P. M.); and the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (grant 1UL 1RR033 176 to A. P. M.).

The authors thank Shilpa Sayana, MD, MPH, for helpful discussion and comments on earlier versions of this article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because data were obtained from secondary sources.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2012. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2013

- 2.De Cock KM, Crowley SP, Lo YR, Granich RM, Williams BG. Preventing HIV transmission with antiretrovirals. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(7):488–488A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2380–2382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen Y, McCauley Met al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montaner JS, Hogg R, Wood Eet al. The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviral therapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. Lancet. 2006;368(9534):531–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montaner JS, Wood E, Kerr Tet al. Expanded highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage among HIV-positive drug users to improve individual and public health outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(suppl 1):S5–S9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GMet al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; the PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma K, Shah K, Mahajan A, Kulkarni S. Clinical Uncertainties, Health Service Challenges, and Ethical Complexities With HIV “Test And Treat”: A Systematic Review. Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42012002883. Accessed February 27, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambrosioni J, Calmy A, Hirschel B. HIV treatment for prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baggaley RF, Fraser C. Modelling sexual transmission of HIV: testing the assumptions, validating the predictions. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(4):269–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bärnighausen T. The role of the health system in HIV treatment-as-prevention. AIDS. 2010;24(17):2741–2742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bärnighausen T, Tanser F, Dabis F, Newell ML. Interventions to improve the performance of HIV health systems for treatment-as-prevention in sub-Saharan Africa: the experimental evidence. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):140–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr D, Amon JJ, Clayton M. Articulating a rights-based approach to HIV treatment and prevention interventions. Curr HIV Res. 2011;9(6):396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendavid E, Brandeau ML, Wood R, Owens DK. Comparative effectiveness of HIV testing and treatment in highly endemic regions. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1347–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brock DW, Winkler D. Ethical challenges in long-term funding for HIV/AIDS. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(6):1666–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruhn CA, Gilbert MT. HIV-2 down, HIV-1 to go? Understanding the possibilities of treatment as prevention. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(4):260–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns DN, Dieffenbach CW, Vermund SH. Rethinking prevention of HIV type 1 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(6):725–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cambiano V, Rodger AJ, Phillips AN. ‘Test-and-treat’: the end of the HIV epidemic? Curr Op Infect Dis. 2011;24(1):19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrico AW. Substance use and HIV disease progression in the HAART era: implications for the primary prevention of HIV. Life Sci. 2011;88(21–22):940–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrico AW, Bangsberg DR, Weiser SD, Chartier M, Dilworth SE, Riley ED. Psychiatric correlates of HAART utilization and viral load among HIV-positive impoverished persons. AIDS. 2011;25(8):1113–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cates W. HPTN 052 and the future of HIV treatment and prevention. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):224–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlebois ED, Das M, Porco TC, Havlir DV. The effect of expanded antiretroviral treatment strategies on the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(8):1046–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlebois ED, Havlir DV. “A bird in the hand …”: a commentary on the test and treat approach for HIV. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1354–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Check Hayden E, Mayer KH, Skeer M, Mimiaga MJ. ‘Seek, test and treat’ slows HIV. Nature. 2010;463(7284):1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. Breakthrough of the year. HIV treatment as prevention. Science. 2011;334(6063):1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MS. HIV treatment as prevention and “the Swiss statement”: in for a dime, in for a dollar? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(11):1323–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen MS. HIV treatment as prevention: to be or not to be? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(2):137–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen MS. HIV treatment as prevention: in the real world the details matter. JAIDS. 2011;56(3):e101–e10221317576 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen MS, Gay CL. Treatment to prevent transmission of HIV-1. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(suppl 3):S85–S95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen MS, McCauley M, Gamble TR. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):99–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen T, Corbett EL. Test and treat in HIV: success could depend on rapid detection. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):204–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford ND, Vlahov D. Progress in HIV reduction and prevention among injection and noninjection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(suppl 2):S84–S87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crowley S, Rollins N, Shaffer N, Guerma T, Vitoria M, Lo YR. New WHO HIV treatment and prevention guidelines. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):874–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeGruttola V, Smith DM, Little SJ, Miller V. Developing and evaluating comprehensive HIV infection control strategies: issues and challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(suppl 3):S102–S107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dieffenbach CW. Preventing HIV transmission through antiretroviral treatment-mediated virologic suppression: aspects of an emerging scientific agenda. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):106–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Thirty years of HIV and AIDS: future challenges and opportunities. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):766–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodd PJ, Garnett GP, Hallett TB. Examining the promise of HIV elimination by ‘test and treat’ in hyperendemic settings. AIDS. 2010;24(5):729–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dombrowski JC, Harrington RD, Fleming M, Golden MR. Letter to the Editor: Treatment as prevention: are HIV clinic patients interested in starting antiretroviral therapy to decrease HIV transmission? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(12):747–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epstein H, Morris M. HPTN 052 and the future of HIV treatment and prevention. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fauci AS, Folkers GK. Investing to meet the scientific challenges of HIV/AIDS. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(6):1629–1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forsyth AD, Valdiserri RO. Reaping the prevention benefits of highly active antiretroviral treatment: policy implications of HIV Prevention Trials Network 052. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu JJ, Bazazi AR, Altice FL. Preserving human rights in the era of “test and treat” for HIV prevention. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):198–199; author reply 199–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garnett GP, Becker S, Bertozzi S. Treatment as prevention: translating efficacy trial results to population effectiveness. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geffen N. When to start antiretroviral therapy in adults: the results of HPTN 052 move us closer to a ‘test-and-treat’ policy. South Afr J HIV Med. 2011;12(3):9 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria Met al. Highly active antiretroviral treatment as prevention of HIV transmission: review of scientific evidence and update. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(4):298–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haire B. Treatment-as-prevention needs to be considered in the just allocation of HIV drugs. Am J Bioeth. 2011;11(12):48–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamlyn E, Jones V, Porter K, Fidler S. Antiretroviral treatment of primary HIV infection to reduce onward transmission. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(4):283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammer SM. Antiretroviral treatment as prevention. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):561–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris M, Montaner JS. Exploring the role of “treatment as prevention.” Curr HIV Res. 2011;9(6):352–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes R, Sabapathy K, Fidler S. Universal testing and treatment as an HIV prevention strategy: research questions and methods. Curr HIV Res. 2011;9(6):429–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heymer KJ, Wilson DP. Treatment for prevention of HIV transmission in a localised epidemic: the case for South Australia. Sex Health. 2011;8(3):280–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoare A, Kerr SJ, Ruxrungtham Ket al. Hidden drug resistant HIV to emerge in the era of universal treatment access in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e10981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holtgrave DR. Potential and limitations of a “test and treat” strategy as HIV prevention in the United States. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(6):678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holtgrave DR, Maulsby C, Wehrmeyer L, Hall HI. Behavioral factors in assessing impact of HIV treatment as prevention. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1085–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jaffe HW. Increasing knowledge of HIV infection status through opt-out testing. J Bioeth Inq. 2009;6(2):229–233 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnston KM, Levy AR, Lima VDet al. Reply to “Evidence is still required for treatment as prevention for riskier routes of HIV transmission.” AIDS. 2010;24(18):2892–2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnston R, Collins C. Can we treat our way out of HIV? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(1):1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnstone-Robertson SP, Hargrove J, Williams BG. Antiretroviral therapy initiated soon after HIV diagnosis as standard care: potential to save lives? HIV/AIDS (Auckl). 2011;3:9–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Amaral CMet al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV transmission risks: implications for test-and-treat approaches to HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(5):271–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman MOet al. Integrated behavioral intervention to improve HIV/AIDS treatment adherence and reduce HIV transmission. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(3):531–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, White Det al. Sexual HIV transmission and antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort study of behavioral risk factors among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(1):111–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, White D, Jones M, Kalichman M. The Achilles’ heel of HIV treatment for prevention: history of sexually transmitted coinfections among people living with HIV/AIDS receiving antiretroviral therapies. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2011;10(6):365–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalichman SC, Eaton L, Cherry C. Sexually transmitted infections and infectiousness beliefs among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for HIV treatment as prevention. HIV Med. 2010;11(8):502–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kippax S, Reis E, de Wit J. Two sides to the HIV prevention coin: efficacy and effectiveness. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(5):393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kippax S, Stephenson N. Beyond the distinction between biomedical and social dimensions of HIV prevention through the lens of a social public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):789–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kretzschmar ME, van der Loeff MF, Coutinho RA. Elimination of HIV by test and treat: a phantom of wishful thinking? AIDS. 2012;26(2):247–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lange JM. “Test and treat”: is it enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):801–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lockman S, Sax P. Treatment-for-prevention: clinical considerations. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, Crepaz N, McMullen H. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24(17):2665–2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mastro TD, Cohen MS. Honing the test-and-treat HIV strategy. Science. 2010;328(5981):976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mayer KH, Krakower D. Antiretroviral medication and HIV prevention: new steps forward and new questions. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):312–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mayer KH, Skeer M, Mimiaga MJ. Biomedical approaches to HIV prevention. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(3):195–202 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mayer KH, Venkatesh KK. Mayer and Venkatesh respond. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):199–200 [Google Scholar]

- 77.McEnery R, Kresge KJ. Test and treat on trial. IAVI Rep. 2009;13(4):14–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McMullen H. HIV treatment and prevention in international perspective. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32(7):1124–1125 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Menon S. Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy and universal HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa: has WHO offered a milestone for HIV prevention? J Public Health Policy. 2010;31(4):385–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Montague BT, Vuylsteke B, Buvé A. Sustainability of programs to reach high risk and marginalized populations living with HIV in resource limited settings: implications for HIV treatment and prevention. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Montaner JS. Treatment as prevention—a double hat-trick. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):208–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AOet al. Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(1):86–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mugavero MJ, Davila JA, Nevin CR, Giordano TP. From access to engagement: measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(10):607–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mykhalovskiy E, Patten S, Sanders C, Bailey M, Taylor D. Beyond buzzwords: toward a community-based model of the integration of HIV treatment and prevention. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ng BE, Butler LM, Horvath T, Rutherford GW. Population-based biomedical sexually transmitted infection control interventions for reducing HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;16(3):CD001220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nguyen VK, Bajos N, Dubois-Arber F, O’Malley J, Pirkle CM. Remedicalizing an epidemic: from HIV treatment as prevention to HIV treatment is prevention. AIDS. 2011;25(3):291–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nichols BE, Boucher CA, van de Vijver DA. HIV testing and antiretroviral treatment strategies for prevention of HIV infection: impact on antiretroviral drug resistance. J Intern Med. 2011;270(6):532–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Novitsky V, Wang R, Bussmann Het al. HIV-1 subtype C-infected individuals maintaining high viral load as potential targets for the “test-and-treat” approach to reduce HIV transmission. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nunn A, Montague BT, Green Tet al. Expanding test and treat in correctional populations: a key opportunity to reduce racial disparities in HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):499–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Owen SM. Testing for acute HIV infection: implications for treatment as prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):125–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seale A, Lazarus JV, Grubb I, Fakoya A, Atun R. HPTN 052 and the future of HIV treatment and prevention. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seng R, Rolland M, Beck-Wirth Get al. Trends in unsafe sex and influence of viral load among patients followed since primary HIV infection, 2000–2009. AIDS. 2011;25(7):977–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Serna-Bolea C, de Deus N, Acacio Set al. Recent HIV-1 infection: identification of individuals with high viral load setpoint in a voluntary counselling and testing centre in rural Mozambique. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shelton JD. A tale of two-component generalised HIV epidemics. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):964–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith K, Powers KA, Kashuba AD, Cohen MS. HIV-1 treatment as prevention: the good, the bad, and the challenges. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6(4):315–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sorensen SW, Sansom SL, Brooks JTet al. A mathematical model of comprehensive test-and-treat services and HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e29098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van de Vijver DA, Boucher CA. Test and treat for prevention of new HIV infections. AIDS Rev. 2010;12(2):123 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Van der Laar MJ, Pharris A. Treatment as prevention: will it work? Euro Surveill. 2011;16(48):1–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Venkatesh KK, Madiba P, De Bruyn Get al. Who gets tested for HIV in a South African urban township? Implications for test and treat and gender-based prevention interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(2):151–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wagner BG, Kahn JS, Blower S, Venios K, Kelley JF. Should we try to eliminate HIV epidemics by using a ‘test and treat’ strategy? AIDS. 2010;24(5):775–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina Eet al. Test and treat DC: forecasting the impact of a comprehensive HIV strategy in Washington DC. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(4):392–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weber J, Tatoud R, Fidler S. Postexposure prophylaxis, preexposure prophylaxis or universal test and treat: the strategic use of antiretroviral drugs to prevent HIV acquisition and transmission. AIDS. 2010;24(suppl 4):S27–S39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wester CW, Bussmann H, Koethe Jet al. Adult combination antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons from Botswana and future challenges. HIV Ther. 2009;3(5):501–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Williams BG, Lima V, Gouws E, Geffen N. Modelling the impact of antiretroviral therapy on the epidemic of HIV: when to start antiretroviral therapy in adults. Curr HIV Res. 2011;9(6):367–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wilson DP, Johnston KM. Evidence is still required for treatment as prevention for riskier routes of HIV transmission. Reply to “Evidence is still required for treatment as prevention for riskier routes of HIV transmission.” AIDS. 2010;24(18):2891–2892; author reply 2892–2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wood E, Milloy MJ, Montaner JS. HIV treatment as prevention among injection drug users. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.National Institutes of Health Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00867048. Accessed June 7, 2011

- 108.HIV Prevention Trials Network HPTN052. Available at: http://www.hptn.org/research_studies/hptn052.asp. Accessed August 30, 2012

- 109.Stop HIV/AIDS Collaborative Seek and treat for optimal prevention of HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://www.stophivaids.ca. Accessed June 7, 2011

- 110.Dabis F. ART for ART Prevention: Introduction of Ongoing or Planned Trials. PowerPoint presented at Consultation on Antiretroviral Treatment for Prevention of HIV Transmission; Geneva, Switzerland; November 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/events/artprevention/dabis.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2010

- 111.Blower S, Kahn J, Okano J. A “test and treat” strategy in South Africa is likely to lead to a self-sustaining epidemic composed of only NNRTI-resistant strains. Paper presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. San Francisco, CA; February 16–19, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jain V, Liegler T, Vittinghoff Eet al. Transmitted drug resistance in persons with acute/early HIV-1 in San Francisco, 2002–2009. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gill VS, Lima VD, Zhang Wet al. Improved virological outcomes in British Columbia concomitant with decreasing incidence of HIV type 1 drug resistance detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(1):98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lambert-Niclot S, Tubiana R, Beaudoux Cet al. Detection of HIV-1 RNA in seminal plasma samples from treated patients with undetectable HIV-1 RNA in blood plasma on a 2002–2011 survey. AIDS. 2012;26(8):971–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Politch JA, Mayer KH, Welles SLet al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy does not completely suppress HIV in semen of sexually active HIV-infected men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2012;26(12):1535–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KRet al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an international association of physicians in AIDS care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–33, W-284–W-294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.National Institutes of Health Community participation in research (RO1). Available at: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-08-074.html. Accessed March 22, 2011

- 118.Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(3–4):462–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Heidari S, Harries AD, Zachariah R. Facing up to programmatic challenges created by the HIV/AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14(suppl 1):S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Imperial College London PopART: population effects of antiretroviral therapy. Available at: http://www1.imperial.ac.uk/departmentofmedicine/divisions/infectiousdiseases/infectious_diseases/hiv_trials/hiv_prevention_technologies. Accessed April 23, 2011

- 121.Bazin B. ART for HIV Prevention. PowerPoint presented at Consultation on Antiretroviral Treatment for Prevention of HIV Transmission. Geneva, Switzerland; November 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/events/artprevention/bazin.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 122.HIV Prevention Trials Network HPTN065. Available at: http://www.hptn.org/research_studies/hptn065.asp. Accessed April 10, 2011

- 123.Webster PD, Sibanyoni M, Malekutu Det al. Using quality improvement to accelerate highly active antiretroviral treatment coverage in South Africa. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(4):315–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sweat M, Morin S, Celentano Det al. Community-based intervention to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16–32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH project accept, HPTN 043): a randomised study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(7):525–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS What countries need: investments needed for 2010 targets. Available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/jc1681_what_countries_need_en.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2011

- 126.World Health Organization Toward universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2008progressreport/en/index.html. Accessed May 19, 2011

- 127.Jürgens R, Cohen J, Tarantola D, Heywood M, Carr R. Universal voluntary HIV testing and immediate antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1079; author reply 1080–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bayer R, Fairchild AL. The genesis of public health ethics. Bioethics. 2004;18(6):473–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Parker R, Aggelton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VAet al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(suppl 2):S67–S79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Killen J, Grady C. What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(5):930–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]