Abstract

Melanoma incidence and the lifetime risk are increasing at an alarming rate in the United States and worldwide. In order to improve survival rates, the goal is to detect melanoma at an early stage of the disease. Accurate, sensitive and reliable quantitative diagnostic tools can reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies, the associated morbidity as well as the costs of care in addition to improving survival rates. The recently introduced quantitative dynamic infrared imaging system QUAINT measures differences in the infrared emission between healthy tissue and the lesion during the thermal recovery process after the removal of a cooling stress. Results from a clinical study suggest that the temperature of cancerous lesions is higher during the first 45–60 seconds of thermal recovery than the temperature of benign pigmented lesions. This small temperature difference can be measured by modern infrared cameras and serve as an indicator for melanoma in modern quantitative melanoma detectors.

Keywords: Melanoma detection, infrared imaging, quantitative imaging, infrared cameras, thermostimulation, thermal recovery

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Over the past two decades the dramatic advances in technology in general and infrared and computer technologies in particular, enabled the development of new, sophisticated medical imaging and diagnostic tools, with an emphasis on quantitative diagnostics. While in the past qualitative infrared visualization has been used to assist medical diagnosis (for example for breast cancer), its value was limited because of the challenges associated with the interpretation of visualization images. Images of the human body recorded by an infrared detector are affected by a variety of factors: the temperature of the skin surface depends on the heat generation of a lesion and the surrounding healthy skin, blood supply, presence of superficial and deeper blood vessels and ambient conditions. In addition, the infrared radiation reaching the detector will be affected by the shape of the surface. Quantitative infrared imaging (QUIRI) allows high accuracy measurements of temperatures, temperature differences and temperature variations over time, which can be induced by thermostimulation, such as heating or cooling. The recently developed QUAINT (Quantification Analysis of Induced Thermography) imaging system implements the QUIRI approach by combining (i) acquisition of infrared radiation by modern, high-sensitivity detectors, (ii) sophisticated computerized image processing to account for object shape and motion as well as ambient conditions, and (iii) computational modeling of the complex thermophysical processes in the human body to better understand the factors affecting the surface temperature distribution. The measurement and computational hardware, along with the computational imaging and modeling tools, have reached the maturity needed to enable true QUIRI, and this opens new avenues in medical diagnostics, monitoring and care. Laboratory studies, computational studies and small scale clinical studies in recent years have demonstrated the ability of QUAINT to detect early stage melanoma by measuring the differences in thermal recovery between lesions and healthy skin. QUAINT holds the promise to become and accurate, easy-to-use, low-cost, quantitative tool for the early detection of melanoma.

FIVE-YEAR OUTLOOK

Measurement, imaging and computer hardware, image and data processing software and computational modeling methods have experienced unprecedented growth over the past two decades. Improved performance is accompanied by a dramatic decrease of size and cost of these devices, enabled by improved modern manufacturing methods. During the next five years we can expect advances in infrared imaging similar to those experienced by portable (handheld) phones or photographic and video cameras over the past decade. Precision, low-cost infrared cameras integrated into a tablet or handheld device similar to a tablet or cell phone are current goals of camera manufacturers: they are to become a reality in the near future. Such advanced hardware together with sophisticated image processing and computational modeling tools opens unique opportunities for clinical screening, diagnostic and monitoring applications. One compelling application area, supported by recent research, is dermatology. The infrared imaging system proposed by researchers in recent studies has the potential of implementation at different levels of care, such as patient self-exams, as well as primary care and specialized dermatology clinics. Therefore this method holds the promise of becoming a quantitative diagnostic tool for skin cancer and a screening tool for early detection of melanoma.

1. INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer and the number of melanoma cases in the US increases at an alarming rate [1,101,102]. Early detection is the key to improving survival in patients with malignant melanoma. Non-invasive imaging systems that allow accurate quantitative detection of melanoma are instrumental in reducing morbidity and mortality as well as the cost of care associated with this disease.

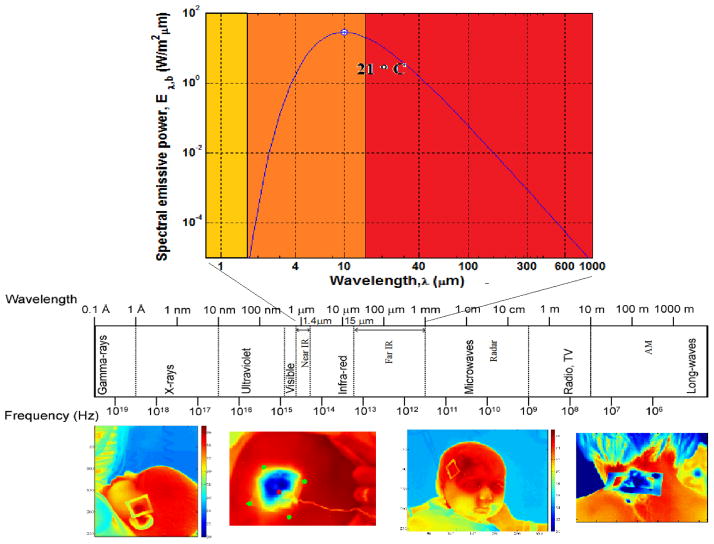

Infrared (IR) thermography (IR imaging) is an imaging technique that allows the detection of electromagnetic radiation emitted by an object (the human body in medical applications) in the infrared domain of the electromagnetic spectrum, the wavelength ranging from 3 to 14 μm (Figure 1). The emissive power, the amount of radiation emitted by a surface, depends on its temperature and increases with increasing temperature as shown in the blackbody radiation spectrum in Figure 1. Changes of emitted radiation in the IR domain can therefore be associated with temperature changes. Since IR images of warmer objects stand out against a colder background, humans or warmer objects become visible against a colder environment, even in total darkness. This property of the infrared imaging system led to a range of military, surveillance (night-vision systems) and industrial applications, which were predominantly qualitative up to date. Military applications have driven a dramatic development of infrared technology over the past decades – a trend accompanied by continuous decrease in cost of the imaging hardware. The decreasing cost led to the development of consumer products as well, and this trend is expected to continue.

Figure 1.

Thermoregulation is the complex biophysical mechanism that maintains the temperature of the human body within desired boundaries and responds to changes in the ambient and other external and internal variations by controlling the rates of heat generation and heat loss. Variations in the temperature of the human body can be caused by disease, physical activity, mechanical or chemical stress and other factors. A large body of evidence exists demonstrating that disease or deviation from normal functioning are accompanied by changes in temperature of the body, which affects the temperature of the skin [2,3]. The behavior of diseased tissue and tumors differs from that of healthy tissue in terms of heat generation and blood supply, because of processes such as increase in metabolic rate, angiogenesis, inflammation, changes in blood vessel morphology, interstitial hypertension and impaired response to homeostatic signals [4,5]. Therefore, accurate data about the temperature of the human body and skin, combined with a high-fidelity thermal model of the body could provide a wealth of information on the processes responsible for heat generation and thermoregulation, in particular about the deviation from normal conditions, often caused by disease. These physiological changes can be imaged by means of infrared thermography in clinical diagnostic applications, and such imaging attempts commenced in the late 1950s. The advantage of IR imaging in medical diagnostics is that the tool is non-invasive, it does not require the irradiation of the body by an external source of radiation (such as visible, X-ray, ultrasound) or the administration of contrast substances.

In the sixties IR imaging was initially embraced by the medical community, and numerous attempts of diagnostic applications were reported in the literature [6–14]. IR imaging was introduced as a clinical tool in dermatology in 1964 and allowed the observation of hyperthermic findings for cutaneous melanoma [6]. However, it was soon discovered that information captured by the detector is influenced by a host of external factors, such as surface emissivity, surface shape (curvature), ambient conditions, and other factors, which made accurate quantitative measurements and rigorous interpretation of data, which are necessary for accurate quantitative diagnosis, challenging or impossible without sophisticated computational and image processing tools. During the past decades infrared imaging was typically used qualitatively, the visual information captured by the detector was converted into a grayscale image or color-coded, and the visual patterns were interpreted by the naked eye, without quantification of temperature or temperature differences, or measuring the temperature evolution of the skin surface as a function of time. The qualitative nature of the infrared information earned the method a reputation of being an inaccurate technique which is not suitable for precision quantitative measurements and diagnostic applications. This is far from the truth today.

In this paper we use the term quantitative diagnosis for a diagnostic process that associates a certain numerical criterion (it can be a maximum temperature difference, average temperature difference, a certain magnitude of heat generation derived from the temperature measurement etc. –caused by increased metabolic activity or blood supply of the melanoma lesion - or a combination of these factors) to a diagnosis. Similar to the criterion which states that a certain body temperature increase measured by a thermometer can be associated with fever caused by disease, a change of a quantitative measure, using a criterion developed based on infrared measurement of temperature distribution on the skin surface and its evolution as a function of time, can serve as an indication of cancer. The criteria are developed based on clinical data gathered in patient studies. QUIRI can be used for quantitative diagnosis of a range of medical conditions, the decision criteria will be unique for each condition. Compared to past qualitative applications of infrared imaging in medicine, QUIRI is a new paradigm in infrared diagnostics offering novel opportunities in screening, diagnostics and monitoring for a variety of medical conditions.

Advances in IR detectors and camera technology, computers, imaging and image processing techniques led to the resurgence of interest in infrared thermography in medical diagnostics and other biomedical and engineering applications [7–11] over the past two decades. Key advances in IR technology involve increased temperature measurement resolution, increased spatial resolution of the infrared sensor array and the ability to record infrared movie sequences with high temporal resolution. The advances in camera hardware led to the decrease in complexity of infrared cameras (for example cooling with liquid Nitrogen was eliminated, replaced by cooling with a miniature Stirling refrigerator), the camera size and power requirements decreased considerably, which led to many portable devices reaching the market. Newest developments involve high temperature resolution sensor arrays that no longer require cooling (uncooled infrared focal plane arrays). Data storage is possible on solid state memory cards inside of the camera housing (which allows portable applications) or on computers interfacing the camera. In addition to the improvements in IR technology, improvements of computer software (automated image acquisition, processing and analysis) and hardware resulted in dramatic progress in the interpretation and quantification of data delivered by IR cameras. Novel, quantitative applications that deliver high-accuracy measurement data are being developed, and they offer new opportunities in quantitative diagnostics and integration through the internet, thereby enabling telemedicine applications. With the current rate of decrease in the cost and size of the devices, infrared cameras and applications similar to smartphones are expected to become available in the near future. In light of these advances infrared diagnostic applications need to be revisited: one of these applications is melanoma screening and diagnosis.

2. QUANTITATIVE DYNAMIC INFRARED IMAGING FOR EARLY DIAGNOSIS OF MELANOMA

Over the past decades several studies evaluated infrared imaging for diagnosis of melanoma [12–14]. The publications describing results of these studies often lacked technical detail necessary to understand measurement approach, measurement sensitivity and error, since the focus of the reports was on the clinical aspect of the study. The approach was prevalently static, with point and shoot imaging and subjective evaluation of the infrared images. In spite of the qualitative approach to imaging, the results of these studies were promising, with sensitivities and specificities similar to those of the standard of care. In recent years quantitative dynamic infrared imaging (relying or induction/thermostimulation in the form of heating and cooling) was introduced to monitor the success of treatment and detect recurrence of advanced melanoma [15]. Our results from recent studies using QUAINT (Quantification Analysis of Induced Thermography) imaging system [16–22], suggest that the static method without sophisticated image processing and motion tracking can possibly detect larger lesions with significant temperature rise [12–14]. However, smaller lesions generating smaller temperature differences require more advanced, enhanced detection techniques, which we highlight in this section. With improvements in measurement technology as well as image and data analysis, better outcomes than those reported in the early studies have become a reality.

In the dynamic IR imaging method the thermal response to an excitation, such as a step change in the thermal boundary conditions, the application or removal of heating or cooling, is measured. Dynamic infrared imaging with thermostimulation (induction) is often used to improve the detection of breast cancer. This is a faster and more robust approach than the passive method, which requires rigorous control of ambient conditions and sufficient time (sometimes hours) for the patient to acclimate to the conditions of the exam room. The dynamic method offers advantages in clinical applications, for which the duration of the measurement and the ease of use are critical, as it is much less dependent on ambient temperatures and conditions. It allows the detection of abnormal features by self-referencing, ie. comparing the responses of healthy and diseased tissue of the same subject, rather than comparing responses of different subjects. While the application of the external forcing slightly increases the complexity of the measurement, the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. The required heating or cooling has to induce small changes in skin temperature, therefore the duration of cooling is short (10–60s) and the temperature levels applied do not cause significant discomfort to the patient (temperature change in the range of 10–15°C) since they are of the level that skin is normally exposed to in everyday life (immersion into water at tap water temperature, wind blowing over the skin on a fall day). Also, typically a small surface area of the skin is cooled (4cm × 4cm in our QUAINT experiment) when a melanoma lesion is evaluated. More details about the possible cooling methods, cooling temperatures and durations are discussed in [20]. Computational modeling was used to better understand the influence of lesions of different sizes, geometries and properties on the surface temperature distribution, to aid the analysis and interpretation of the infrared images. Key results from the computational modeling efforts are summarized in [16].

When the skin surface is cooled in active IR imaging, the difference in the thermophysical properties of the lesion (located near or underneath the surface), compared to healthy tissue, results in identifiable temperature patterns and temperature differences between the lesion and the surrounding healthy tissue during the thermal recovery phase. These differences are caused by the increased metabolism of cancerous lesions as well as by increased blood perfusion that provides the necessary nutrition for the accelerated growth. These surface temperature patterns will differ from those present in the steady state situation observed during passive IR imaging. Therefore the measurement process consists of three phases: (i) the initial phase when the skin is exposed to nominal ambient conditions, (ii) the cooling phase which is followed by (iii) the thermal recovery phase.

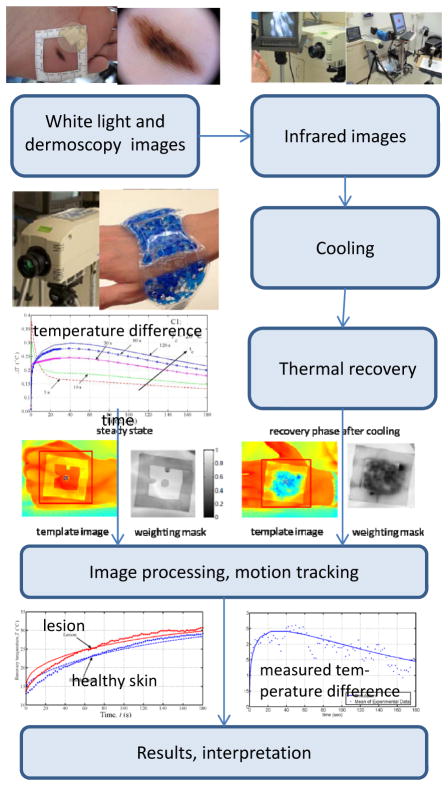

The steps in the QUAINT imaging process [16,18,19,20], obtained with a laboratory prototype imaging system, are illustrated in Figure 2. The imaging starts with the application a rectangular template to the region of interest, centered around the lesion. A white light photograph of the domain is taken first, followed by an infrared image of the reference steady state situation under ambient conditions (Figure 2). The lesion is not visible in the reference steady state infrared image, implying that the heat generation is too small to me measured at the skin surface under static conditions. The skin is then cooled by blowing cold air or applying a cooling patch at 15–25°C for the duration of up to 1 minute. After removing the cooling load, the dynamic thermal response of the structure is acquired using IR imaging. Infrared images recorded during the thermal recovery are shown in Figures 2 and 3. The results suggest that thermal contrast between the lesion and the healthy surrounding tissue is enhanced by the cooling. After the postprocessing steps, the temperature of the lesion and healthy tissue are plotted as function of time during the thermal recovery, as shown in Figure 3e. The results demonstrate that there is a significant difference in temperature (of the order of 0.3 °C for a 2mm diameter 0.4mm deep lesion) between the melanoma lesion and healthy tissue during thermal recovery, whereas benign pigmented lesions have the same thermal recovery as the healthy tissue. This temperature difference can be easily and accurately measured using modern IR cameras. More details about the method and sample analyses of lesions with corresponding measurement data of interest are available in the references [16,18,19,20]. This imaging technique also holds the promise of allowing the staging melanoma based on the magnitude of temperature differences and other thermal characteristics of the lesion during the recovery process. The problem of non-invasive, quantitative staging is a subject of current research efforts.

Figure 2.

Imaging and image processing steps for quantitative detection of melanoma using QUAINT.

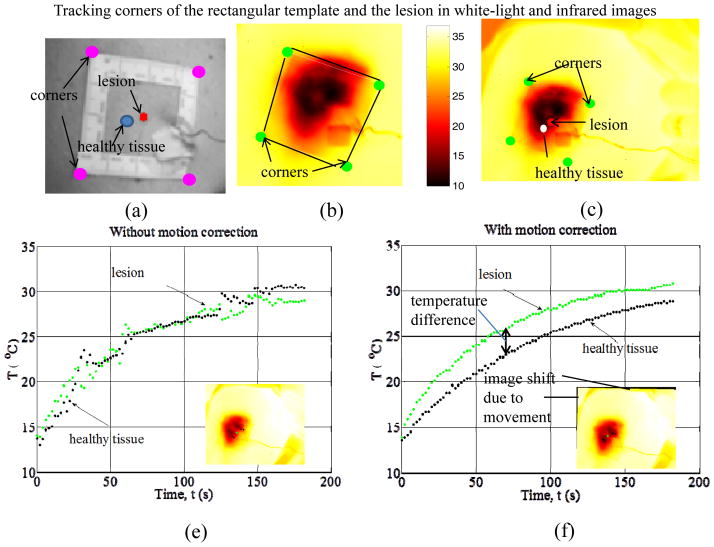

Figure 3.

Image analysis steps and thermal recovery temperature profiles in melanoma detection using QUAINT: a) white light image with characteristic points for image analysis (rectangular marker and lesion center), b) edge and corner detection in the IR image, c) lesion contour registration in the IR images, d) temperature profiles without motion correction (information loss) and e) after motion correction, demonstrating the presence of temperature difference – to be used in quantitative diagnostic applications - between a cancerous lesion and the surrounding healthy skin.

IR imaging is a non-contact method, and this feature offers advantages in terms of ease of application and the ability to image larger surface areas and multiple lesions. However, during the 30–60s thermal recovery phase, involuntary movements of patient unavoidable in a clinical environment (for example breathing) can cause small spatial displacement of lesions that can lead to deterioration of the measurement data, as illustrated in Figure 3d. Such effects can render the measurements useless. Accurate measurements therefore require accurate tracing of the transient temperature response at any specific point on the skin. To accomplish this, it is necessary to apply motion tracking/compensation processing on the IR video sequence. Data after incorporating motion tracking corrections are shown in Figure 3e. The results indicate significant differences in thermal recovery between the cancerous lesion and healthy skin and demonstrate the ability to detect melanoma early.

The QUAINT imaging was initially tested in a patient study with 37 patients, as reported in [18,19]. A larger clinical study is currently underway. Lesions were scanned prior to biopsy. Three of the 37 lesions were cancerous (determined by biopsy) and all three were successfully detected using QUAINT. There were no false positives or false negatives detected using our dynamic IR imaging tool. The measured temperature difference for a 2mm diameter, 0.44mm deep melanoma lesion was around 0.3°C. We also measured a temperature difference for a melanoma in situ lesion, however, the ability of the imaging system to detect melanoma in situ requires further study. Therefore, our imaging systems holds the promise to reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies (current statistics show that one melanoma is found in 20–40 biopsies) as well as improve the early detection of melanoma, which can reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease.

3. CONCLUSIONS

This brief review discusses promising developments in infrared imaging and supportive technologies that meet the needs and challenges for developing sensitive, reliable, robust and inexpensive quantitative diagnostic tools for early detection of melanoma and potentially staging of the disease in vivo. The goal is to introduce automated diagnostic instruments for screening of individual lesions, discrimination of cancerous lesions on a larger portion of the body and full body screening. Screening scanners used by patients would alert them to changes in a lesion and a potential problem, similar to blood pressure cuffs or diabetes testing equipment. These scanners would also suitable for use in primary care facilities, which are the first point of contact for many patients. More sophisticated detectors can be using in specialized centers and these would potentially allow the staging of the lesion. One challenge in wider implementation of quantitative diagnostics is the fact that diagnostic instruments are expected to compete in price and ease of use with visual inspection, the current standard of care. Funding for large scale studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of imaging systems along with the complex and lengthy governmental approval process are additional challenges quantitative diagnostic tools face. The rapid development of advanced detectors and decrease in cost are very promising, and integration of complex diagnostic features into a smartphone-type device is becoming a reality.

KEY ISSUES.

Melanoma incidence is increasing at an alarming rate in the US and worldwide. For melanoma detected at an early stage of the disease, the 5-year survival rate is about 99% and drops dramatically, to 15%, for patients with advanced disease [1,101, 102].

Accurate, sensitive, and objective quantitative diagnostic instruments for the detection and diagnosis of melanoma at an early stage of the disease would allow avoiding unnecessary biopsies, and ultimately reduce the cost of care, as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease.

Advances in sensors and instrumentation, image processing tools and computational modeling led to developments in quantitative infrared imaging QUIRI in medical systems to allow accurate measurement of very small temperature differences (of the order of 30mK). These devices measure the infrared radiation emitted by the skin: the measurement is non-invasive and does not require exposing the body to external radiation or the administration of a tracer.

Cancerous skin lesions, such as melanoma, generate more heat and have increased blood supply compared to the surrounding healthy skin, and these differences can be measured by QUIRI [15,18,19].

Recent studies using the QUAINT imager [16,18,19] suggest that cancerous lesions reheat faster after the removal of a cooling stress than the surrounding healthy skin or benign pigmented lesions, and this temperature difference can be accurately measured using modern quantitative infrared imaging techniques.

The magnitude of this temperature difference, along with other characteristics of the reheating, can be used to quantitatively detect, diagnose and potentially even stage melanoma [16,17,18,19].

Acknowledgments

Images and photographs for this review were taken or contributed by Rajeev Hatwar, Tze-Yuan Cheng and Muge Pirtini Cetingul. The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health NCI Grant No. 5R01CA161265-02, the National Science Foundation Grant No. 0651981 and the Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust through the Cancer Center of the Johns Hopkins University.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

*of interest

**of considerable interest

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones BF. A reappraisal of the use of infrared thermal image analysis in medicine. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17 (6):1019–1027. doi: 10.1109/42.746635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anbar M. Clinical thermal imaging today—shifting from phenomenological thermography to pathophysiologically based thermal imaging. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 1998;17 (4):25–33. doi: 10.1109/51.687960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anbar M. Assessment of physiologic and pathologic radiative heat dissipation using dynamic infrared imaging. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;972:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ring EFJ. Progress in the measurement of human body temperature. IEEE Eng Med Bio Mag. 1998;17:19–24. doi: 10.1109/51.687959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasfield RD, Laughlia JS, Sherman RS. Thermography in the management of cancer: a preliminary report. Ann NY Aca Sci. 1964;121:235–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb13699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulyaev YV, Markov AG, Koreneva LG, Zakharov PV. Dynamical infrared thermography in humans. IEEE Eng Med Bio. 1995;14:766–771. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diakides NA. Infrared imaging: an emerging technology in medicine. IEEE Eng Med Bio. 1998;17:17–18. doi: 10.1109/memb.1998.687958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaviov VP, Vaviova EV, Popov DN. Statistical analysis of the human body temperature asymmetry as the basis for detecting pathologies by means of IR thermography. Thermosense XXIII, Proceedings of SPIE. 2001;4360:482–491. [Google Scholar]

- 10*.Fauci MA, Breiter R, Cabanski W, et al. Medical Infrared Imaging - differentiating facts from fiction, and the impact of high precision quantum well infrared photodetectors camera systems, and other factors, in its reemergence. Infrared Phys Tech. 2001;42:337–344. A review of advances in infrared technology and its impact on medical imaging. [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Ring EFJ, Ammer K. Infrared thermal imaging in medicine. Physiol Meas. 2012;33:R33–R46. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/3/R33. A review of recent advances in applications of infrared imaging in medicine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Cristofolini M, Piscioli F, Valdagni C, Della Selva A. Correlations between thermography and morphology of primary cutaneous malignant melanomas. Acta Thermogr. 1976;1:3–11. Early study using infrared imaging for detection of melanoma. [Google Scholar]

- 13*.Hartmann M, Kunze J, Friedel S. Telethermography in the diagnostic and management of malignant melanomas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00629.x. Early study using infrared imaging for detection of melanoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Di Carlo A. Thermography and the possibilities for its applications in clinical and experimental dermatology. Clin Dermatology. 1995;13:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00073-o. Early study using infrared imaging for detection of melanoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Santa Cruz GA, Berotti J, Martin J, et al. Dynamic Infrared Imaging of Cutaneous Melanoma and Normal Skin in Patients Treated With BNCT. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67:S54–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.093. Important study discussing the use of quantitative dynamic infrared imaging for monitoring the recurrence of melanoma after radiation treatment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Herman C, Pirtini Cetingul M. Quantitative Visualization and Detection of Skin Cancer Using Dynamic Thermal Imaging. J Vis Exp. 2011;(51):e2679. doi: 10.3791/2679. Important video article visualizing the quantitative dynamic infrared imaging method for the detection of melanoma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Pirtini Cetingul M, Herman C. Heat transfer model of skin tissue for the detection of lesions: sensitivity analysis. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:5933–5951. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/19/020. Important article describing a computational thermal model of melanoma surrounded by healthy tissue, serves as foundation for the interpretation of data obtained by quantitative dynamic infrared imaging. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Pirtini Cetingul M, Herman C. Quantification of the thermal signature of a melanoma lesion. Int J Thermal Sci. 2011;50:421–431. Important paper describing computed and measured thermal responses after the removal of cooling for melanoma, benign pigmented lesions and healthy skin. Demonstrates the temperature differences detected during thermal recovery between melanoma and benign lesions. [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Pirtini Cetingul M, Herman C. The Assessment of Melanoma Risk Using the Dynamic Infrared Imaging Technique. J Thermal Science and Engineering Applications. 2011;3:031006–1–031006–9. Important paper discussing thermal signatures of cancerous (melanoma) and benign pigmented lesions. Demonstrates the feasibility of the dynamic quantitative infrared imaging method for the quantitative detection of melanoma. [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Cheng TY, Herman C. Optimization of skin cooling for thermographic imaging of near-surface lesions. Proc. ASME 2011 International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition IMECE; 2011 November 11–17, 2011; Denver, Colorado, USA, IMECE. 2011. pp. 2011–65221. Paper evaluates cooling methods, temperatures and durations for quantitative dynamic infrared imaging of melanoma. [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Pirtini Cetingul M, Cetingul HE, Herman C. Analysis of transient thermal images to distinguish melanoma from dysplastic nevi. Proceedings of the SPIE Medical Imaging Conference; February 12–17, 2011; Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA. 2011. pp. 7963–130. Paper discussing the image processing and motion tracking steps necessary for high-accuracy measurement of temperature differences as a function of time required for the early detection of melanoma. [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Herman C. Emerging technologies for the detection of melanoma: achieving better outcomes. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 2012;5(1):195–212. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S27902. This paper compares emerging technologies for the detection of melanoma, discusses the requirements for different applications and the phases of instrument development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Melanoma of the Skin. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html.

- 102.Skin Cancer Foundation website. 2010 http://www.skincancer.org/Skin-Cancer-Facts/