Abstract

Williams syndrome (WS) is a genetic condition characterized by atypical brain structure, cognitive deficits, and a life-long fascination with faces. Face recognition is relatively spared in WS, despite abnormalities in aspects of face processing and structural alterations in the fusiform gyrus, part of the ventral visual stream. Thus, face recognition in WS may be subserved by abnormal neural substrates in the ventral stream. To test this hypothesis, we used functional magnetic resonance imaging and examined the fusiform face area (FFA), which is implicated in face recognition in typically developed (TD) individuals, but its role in WS is not well understood. We found that the FFA was approximately two times larger among WS than TD participants (both absolutely and relative to the fusiform gyrus), despite apparently normal levels of face recognition performance on a Benton face recognition test. Thus, a larger FFA may play a role in face recognition proficiency among WS.

Introduction

Williams syndrome (WS) is a genetic condition associated with micro deletions on chromosome 7q11.23 (Hillier et al., 2003). This condition is associated with a specific combination of neuroanatomical, sensory, and cognitive characteristics (Bellugi et al., 2000), providing a rare opportunity to study the relations among genes, cognition, and brain structure and function. WS often involves intellectual deficits, substantial deficits in visual-spatial construction, heightened emotionality, and eagerness for face-to-face interactions, known as hypersociability (Järvinen-Pasley et al., 2008). Hypersociability includes an exaggerated tendency to view human faces during infancy (Mervis et al., 1998) and adulthood (Riby et al., 2008, 2009; Riby and Hancock, 2009a,b). Interestingly, proficiency in face-identity recognition is reportedly similar among WS and typically developed (TD) healthy participants, despite the latter's intellectual deficits, and better among WS than IQ-matched, developmentally delayed participants (Bellugi et al., 2000). This apparent sparing of face-recognition proficiency in WS is intriguing, given abnormalities in other aspects of face processing (Mills et al., 2000; Karmiloff-Smith et al., 2004), significant reductions in total brain-volume (Reiss et al., 2004), and abnormalities in cortical thickness along parts of the ventral visual processing stream, namely the fusiform gyrus (Thompson et al., 2005). Thus, one hypothesis suggests that face-identity recognition in WS relies on an altered functional organization of face-selective cortex in the ventral stream. However, the neural substrates underlying face-identity recognition in WS are not well characterized.

Face recognition in TD adults involves the fusiform gyrus, where functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed regions, such as the fusiform face area (FFA), responding more strongly to faces than to objects or to places (Kanwisher et al., 1997). The FFA is implicated in face perception (Tong et al., 1998; Grill-Spector et al., 2004) and identity recognition (Druzgal and D'Esposito, 2001; Golby et al., 2001; Ranganath et al., 2004; Nichols et al., 2006). Larger FFA volumes are associated with improvements in face recognition proficiency during development (Golarai et al., 2007). Only a few fMRI studies have examined fusiform gyrus responses in WS, reporting either subtle (Paul et al., 2009) or no between-group differences in activations to faces (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2004; Mobbs et al., 2004; Sarpal et al., 2008) or to nonface stimuli (Mobbs et al., 2007). However, none of these studies of WS defined the face- or object-selective regions according to standard methods used in TD participants (Kanwisher et al., 1997; Grill-Spector et al., 2001; Golarai et al., 2007) or examined these regions' sizes, response profiles, or associations with proficiency in face recognition.

Here, we used fMRI to examine face- and object-selective responses among adults with WS, compared with TD adults, relating brain measures to behavioral measures of face-identity matching and IQ. We examined between-group differences in absolute FFA size and also relative to the anatomical size of the fusiform gyrus, as well as response amplitudes to faces and objects. To examine the specificity of our findings to face stimuli and the FFA, we repeated these measurements for object-selective activations in the fusiform gyrus and face-selective activations in the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) and the amygdala.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review boards of The Salk Institute, University of California at San Diego (UCSD), and Stanford University approved the procedures. Participants provided informed written consent for the study. Sixteen individuals diagnosed with WS, ages 19.79 to 48.48 years (mean ± STD, 29.67 ± 9.22 years; 7 females; 2 left-handed) and 15 TD individuals, ages 17.07 to 45.74 years (31.69 ± 9.73 years; 7 females) participated in this study. Mean age of the 13 participants in each group whose fMRI data were included in the study is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance of WS and TD participants as raw scores on standardized tests of general intelligence and Benton face recognition

| Age | Intelligence test (WAIS-III or WAIS-R) |

BUP scale 0–27 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ_FS | IQ_P | IQ_V | |||

| WS, N = 13 | 29.9 ± 2.6 | 66.3 ± 2.5* | 71.08 ± 2.3* | 64.92 ± 2.5* | 20.8 ± 0.7 |

| n = 13 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | |

| Subset of WS %Res matched to TD, N = 8 | 27.7 ± 3.7 | 63.6 ± 3.7* | 68.9 ± 3.2* | 62.9 ± 3.9* | 19.8 ± 0.9 |

| n = 8 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 8 | |

| TD, N = 13 | 30.0 ± 2.3 | 119.0 ± 4.2 | 117.9 ± 3.5 | 115.6 ± 4.6 | 22.63 ± 1.05 |

| n = 13 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 8 | |

IQ_FS, Overall IQ scores, IQ_P, performance IQ; IQ_V, verbal IQ; BUP scale, scale of raw score on the short form Benton recognition score on upright faces. All scores are reported as mean ± SD.

*p < 0.0001 compared to TDs.

WS and TD participants were recruited nationally and from the local community around University of California, San Diego (The Salk Institute and UCSD) and Stanford University as part of a multisite project. The genetic diagnosis of WS was based on fluorescent in situ hybridization probes for elastin, a gene consistently found to be deleted in WS (Ewart et al., 1993). All participants with WS had typical deletions and exhibited the clinical phenotype associated with this condition (Korenberg et al., 2000). Participants with a history of complicating neurological conditions were excluded from the study. TD participants had no history of medical, psychiatric, neurological or cognitive impairment.

fMRI Experiment

Stimuli.

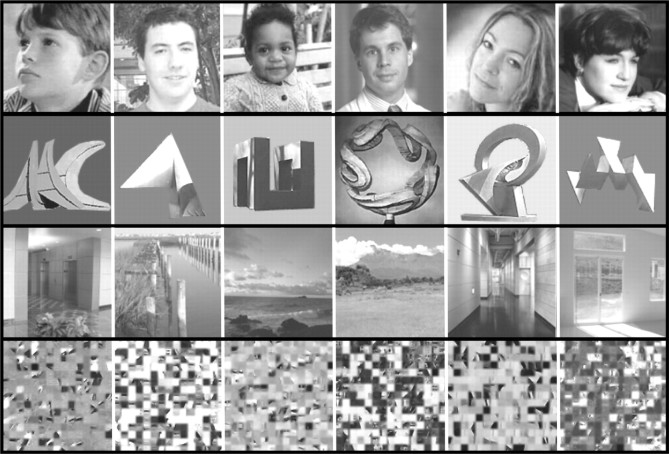

Participants viewed a total of 768 grayscale photographic images from the following four categories: faces (male and female of various ages, races, facial expressions, and views), objects (abstract sculptures), places (indoor and outdoor), and textures (created by randomly scrambling object pictures into 225, 8 × 8, pixel squares) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Visual stimuli during fMRI. Participants viewed unique instances of 768 gray-scale photographic images in six blocks for each of the categories of faces (males and females of various ages, races, facial expressions, and views), objects (abstract sculptures), places (indoor and outdoor), and textures (created by randomly scrambling object pictures into 225, 8 × 8, pixel squares).

Each stimulus category was presented in six blocks. Block duration was 8 s, during which 32 exemplars from a given category were sequentially displayed, each for ∼500 ms. None of the images were repeated during the experiment. A 16 s block of blank screen preceded the beginning and another followed the end of the run. Images were projected onto a mirror mounted on the MRI coil (visual angle ∼15°) via a Macintosh G3 computer using Matlab 5.0 (Mathworks) and Psychtoolbox extensions (http://www.psychtoolbox.org). Images from the various categories were similar in their mean luminance when projected on the screen at the scanner as measured by a Minolta photometer (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We found no significant difference between category differences in mean luminance (p < 0.2) and within-category variations (438−525 C/m2) far exceeded the subtle between-category variations in mean luminance (∼5 C/m2).

Task.

Participants were instructed to view each image passively. No behavioral responses were collected during the scan.

Scanning.

Brain imaging was performed on a 3 tesla whole-body Signa MRI scanner (General Electric) at the Lucas Imaging Center, Stanford University, equipped with a quadrature birdcage head coil. Participants were instructed to relax and stay still. We placed padding around each participant's head to stabilize the head position and reduce motion-related artifacts during scanning. First, a high-resolution three-dimensional fast spoiled gradient-recalled acquisition in a steady state (SPGR) anatomical scan (124 sagittal slices, 0.938 × 0.938 mm, 1.5 mm slice thickness, 256 × 256 image matrix) of the whole brain was obtained. Next, functional images were obtained using a T2*-sensitive gradient echo spiral pulse sequence (Glover and Law, 2001). Full brain volumes were imaged using 32 slices (4 mm thick plus 1 mm skip), oriented parallel to the line connecting the anterior and posterior commissures. Brain volume images were acquired continuously with repetition time = 2000 ms, echo time = 30 ms, flip angle = 80°, field of view = 240 mm, 3.75 mm × 3.75 mm in-plane resolution and 64 × 64 image matrix. A total of 205 time frames were acquired during a ∼6.8 min scan.

Preprocessing.

The first seven functional volumes during the initial blank stimuli were discarded to allow for T1 equilibration. Functional images were median-filtered to reduce transient blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) artifacts using an in-house algorithm, realigned to correct for motion, and temporally filtered (high-pass, 56 s cutoff) using a statistical parametric map software package (SPM2; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology). Data were not spatially smoothed except for one analysis to test the effect of smoothing on our results using a 6 mm full-width at half-maximum (see Fig. 2). Data were not spatially normalized to a template and all analyses were conducted in each participant's native space. Data from three WS participants and two TD participants were not used for further analysis due to excessive motion (>2 mm) or signal drop out.

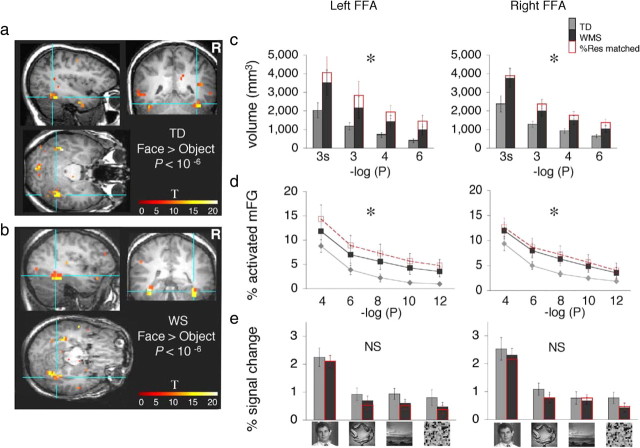

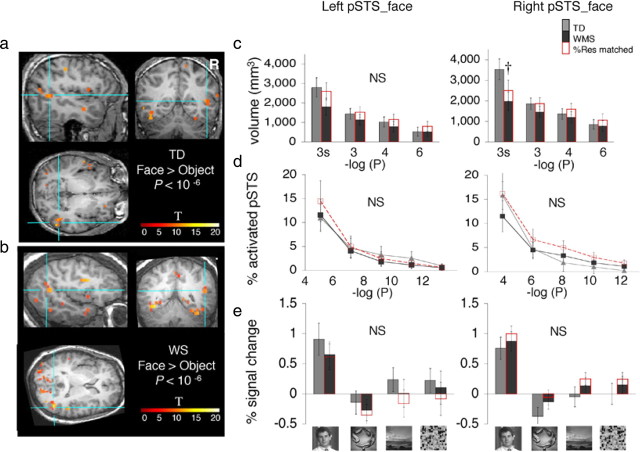

Figure 2.

Face-selective activations in the fusiform gyrus in WS and TD patients. a, The FFA was defined in each participant as a cluster of contiguous face-selective voxels with activation peaking in the mid-fusiform gyrus (faces > objects, p < 10−6, uncorrected). Blue lines point to the right FFA in coronal, sagittal, and horizontal views from a representative TD participant. Color bar indicates t values. b, Same as a but from a representative WS participant. c, Bars show the volume of the FFA, defined as a contiguous cluster of activation peaking in the mid-fusiform gyrus (mFG) plotted against the minus logarithm (base 10) at three different thresholds (faces > objects, p < 10−3, p < 10−4, p < 10−6), using nonspatially smoothed data, or at p < 10−3, using spatially smoothed data (3s). At each threshold, FFA volume was averaged across 13 TD participants (light gray), and 13 WS participants (black). Error bars show group SEM. Red bars, WS participants matched to the TD group for %Res in FUS. The volume of the rFFA was significantly larger among WS than TD participants across all four comparisons (WS > TD, *p < 0.05, two-tailed F test, repeated-measures ANOVA). d, For each participant, the percentage of mid-fusiform activation was calculated as the total volume of face-selective voxels (faces > objects), regardless of contiguity, within the anatomically defined left or right mid-fusiform gyrus, divided by the volume of that anatomical ROI. The percentage of mid-fusiform activation is plotted against the minus logarithm (base 10) at six statistical thresholds between 10−4 and 10−12 (uncorrected) for all participants [TD in gray and WS (WMS) in black], and for a subset of WS participants who were matched to TD for %Res in FUS (in red). Diamonds, TD, n = 13; black squares, WS (n = 13); red squares, WS matched to TD participants for %Res in FUS (n = 8). Error bars show group SEM. The proportional volume of face-selective activations relative to the volume of the FUS was significantly higher in WS than in TD across the various thresholds tested in both (WS > TD, *p < 0.05, two-tailed F test, repeated-measures ANOVA). e, FFA's (faces > objects, p < 10−4, uncorrected) responses to faces, objects, places, and textures based on β coefficients derived from the GLM for each image category relative to baseline. Bars represent each group's data as in c. Amplitude of responses to visual stimuli were not significantly different among groups and there were no significant (NS) group-by-category interactions. Note that the response magnitudes are not independent of the data used to select the FFA. Error bars show group SEM.

General linear model.

For each participant and using a general linear model (GLM) in SPM2, statistical modeling was performed on preprocessed functional images, excluding images with an average BOLD signal exceeding 2 SD from the mean. In any given participant, the number of excluded images did not exceed 5% of the time series.

The resulting t-maps corresponding to the contrast and threshold of interest (uncorrected for multiple comparisons) were overlaid on the individual's high-resolution T1 image, which was coregistered to the mean motion-corrected and nonsmoothed functional image.

Region of interest creation.

Four types of regions of interest (ROIs), anatomical, functional-cluster, functional-noncluster, and constant sized, were created for each participant.

Anatomical ROIs were manually delineated with BrainImage software (cibsr.stanford.edu/tools) for each participant, based on their non-normalized high-resolution anatomical image (SPGR). All of the anatomical ROIs were drawn by an experienced researcher who was blind to the identity of the participants.

The anatomical ROIs of the fusiform (FUS) in all participants included gray and white matter of the fusiform gyrus between the lateral occipitotemporal sulcus and the lateral bank of the collateral sulcus (see Fig. 3). The anterior-to-posterior extent of the fusiform gyrus was limited to a region between the posterior edge of the amygdala and a coronal slice at the level of the most anterior point of the parietal-occipital sulcus (Duvernoy, 1999).

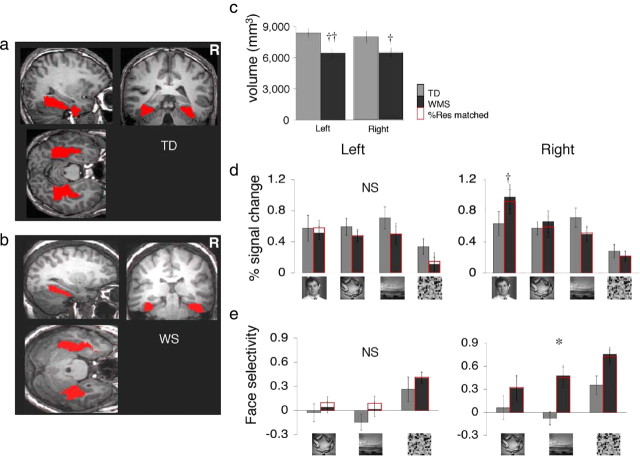

Figure 3.

Anatomical ROIs of the mid-fusiform gyrus (FUS). a, Anatomical boundaries of the FUS were drawn for each participant in the right and left hemisphere to include gray and white matter. In red are the anatomical FUS ROIs in coronal, sagittal, and horizontal views from a representative TD participant. b, Same as a but from a representative WS participant. c, The volume of the gray matter within the anatomically defined FUS. Gray, TD adults, n = 13; black, WS (WMS) adults, n = 13. Error bars show SEM for each group (TD > WS; †p < 0.001, ††p < 0.0001, t test). d, From the anatomically defined FUS ROIs, we calculated response amplitudes to faces, objects, places, and textures based on β coefficients derived from the GLM for each image category relative to baseline. Gray and black bars represent each group's data as in c. Red bars show data from a subset of eight WS participants matched to the TD group for %Res (which reflects BOLD-related noise and goodness of GLM fit) in FUS. The overall response amplitudes in the WS and TD groups were not statistically different. However, in the right FUS there was a significant group-by-category interaction (p < 0.002, F test, ANOVA), as response to faces was higher in WS than in TD participants (†p < 0.05, one-tailed t test). The response magnitudes are independent of the anatomical data used for delineating the ROI. e, Face selectivity was calculated based on the differential responses to faces versus one of the other stimulus categories (object, place, or texture) as indicated along the x-axis [e.g., (face − object)/%Res] (see Materials and Methods). Positive values along the y-axis indicate preference for faces, and negative values indicate preference for objects or places or textures, as indicated by pictures. Bars represent TD and WS groups as in d. Error bars show SEM. Face selectivity was significantly higher among WS compared with TD participants in the right hemisphere (*p < 0.015, F test, repeated-measures ANOVA). NS, Not significant.

The anatomical ROIs of the entire STS were defined and designated into sections (anterior, posterior and ascending limb) (see supplemental Fig. 3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) by using anatomical landmarks derived from a standardized human brain atlas of cerebral sulci (Ono et al., 1990). The ascending limb of the pSTS was defined as the sulcal gray matter directly adjacent to the angular gyrus (Allison et al., 2000). Tracing was initiated at the first posterior bisection point along the STS and terminated at the point where the STS either bisected again or ended.

The anatomical ROIs of the amygdala in all participants were drawn at the amygdala gray matter boundary with the surrounding white matter along the medial, inferior, and lateral surfaces of amygdala (see supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The superior boundary of the amygdala excluded any gray matter above a horizontal line through the endorhinal sulcus.

Functional (cluster) ROIs for FFA, pSTS_face, and AMG_face were defined in each participant as activations that peaked in the anatomically defined FUS, pSTS, and amygdala, respectively, based on the conventional definitions as the contiguous suprathreshold voxels that responded more to faces than abstract objects at p < 10−3, 10−4, and 10−6. Functional ROIs for FUS_obj were similarly defined in each participant as the contiguous suprathreshold voxels that responded more to abstract objects than to textures at p < 10−3, 10−4, and 10−6, peaking in the FUS. Thresholds were based on whole brain analysis, uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Functional (noncluster) ROIs included all suprathreshold voxels (regardless of clustering) within the relevant anatomical boundaries of the FUS, pSTS, or amygdala (i.e., anatomical ROI) for the contrast of interest (that is, faces > abstract objects for FFA, pSTS_face, and AMG_face or abstract objects > text for FUS_obj) at five different statistical thresholds (10−4 < p < 10−12). Thresholds were based on whole brain analysis, uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Constant-sized spherical ROIs (see supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) included all voxels (regardless of activations) within a sphere that was centered at the peak of the individually defined FFA. Four concentric spheres were created with the following volumes: (1) 6 voxels, which was the minimum volume of the FFA across all participants, (2) the group average volume of the FFA in TD participants, (3) 1.5 times the volume of TD, and (4) the group average volume of the FFA in WS participants.

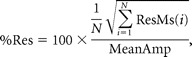

Estimation of residual error of GLM.

This reflects the discrepancy between the GLM estimates and the time course BOLD data, and thus is an inclusive measure of BOLD-related noise (e.g., due to motion during scan) and goodness of GLM fit. The residual variance of the GLM was estimated per voxel using ResMS.img generated by SPM2. We then measured the mean residual error across anatomical ROIs:

|

where N is the number of voxels in the anatomical ROI and MeanAmp is the mean amplitude of the BOLD response across the ROI,

The estimation of residual error of GLM (%Res) was calculated separately across the anatomical ROIs of the FUS, pSTS, and amygdala. We then reanalyzed our data for participants matched for BOLD-related confounds by removing the WS participants with the highest %Res within each anatomical ROI.

Extraction of ROI responses.

We calculated average responses across ROIs based on the GLM estimates of the β coefficients (βx) for each experimental condition (faces, objects, places, and textures) relative to baseline (β0) per voxel as percentage signal change = 100 × (βx/β0).

Measure of face selectivity.

We calculated a measure of face selectivity for the anatomical ROIs of the right or left FUS (see Fig. 3e), based on the differential response to faces compared with one other stimulus category, relative to the residual error of the GLM: , where within a given ROI, βface is the average β estimate for faces, βx is the average β estimate for a nonface category (i.e., object, place, or texture), and %Res is the mean residual error of the GLM within the ROI (see above).

Behavioral measures.

Outside the scanner, we administered standardized intelligence tests, including WAIS-R or WAIS-III, to measure performance IQ (P_IQ), verbal IQ, and overall IQ (see Table 1).

We also examined face recognition proficiency among WS (n = 13 of 13) and TD (n = 9 of 13) participants by measuring performance on a Benton recognition test on upright faces (Benton et al., 1978, 1983). This test consists of recognition of facial identity with simultaneous presentation of the study and test faces, the latter involving changes in lighting or viewpoint of the target face, among a number of distracters. Each participant viewed a target upright face and several upright test faces presented in a multiple choice format and was asked to find one or more instances of the target face identity among the test faces. In more difficult items, test faces included transformations of the target faces involving changes in lighting or viewing angle. If more than one Benton test was conducted on a participant, we used that participant's best Benton score (three WS participants). Performance is reported as raw scores in Table 1 on a scale of 0 to 27 (using the short form, 1 pt for each correctly chosen face) and as percentage of correct choices in Figure 7. We chose this task for two reasons. First, it has been previously used in reports of preservation of face recognition proficiency in WS (Bellugi et al., 2000). Second, it predominantly involves perceptual processes while excluding the potential contribution of memory processes, which are also affected in WS (Vicari and Carlesimo, 2006; Sampaio et al., 2008; Yam et al., 2008).

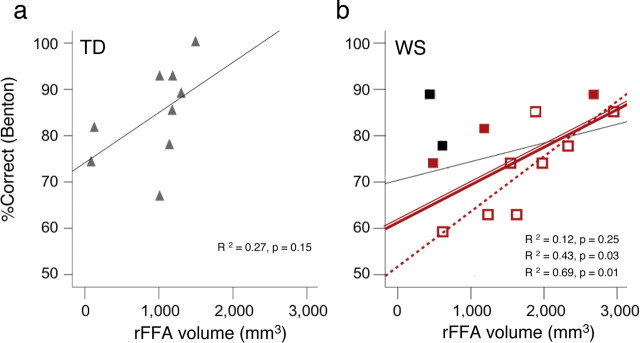

Figure 7.

Performance of TD and WS groups on an independent Benton face recognition task on upright faces. a, Performance on the Benton recognition of upright faces is plotted as percentage of correct responses against the FFA volume (faces > objects, p < 10−4, uncorrected) for the subset of TD participants who took the test (n = 9). The correlation between performance on the Benton test and FFA volume did not reach statistical significance. b, Performance of WS on the Benton test is plotted against rFFA volume (faces > objects, p < 10−4, uncorrected) for all participants with Benton scores (solid red squares, double solid red line), the subset of WS that were statistically not different from TDs on %Res [after removing the participants with the highest %Res in the right FUS (black squares, black line) and the subset of WS who were matched on %Res in right FUS with TD (open red squares, dashed red line)]. There was a significant correlation between performance on the Benton test and FFA volume among the later two subsets of WS participants.

Statistical methods for between-group comparisons.

For between-group comparisons of the volume of the anatomical and functional ROIs (for a specific threshold for activation maps), participants' data were averaged for each of the WS and TD groups. After testing for equality of variances between groups (Levine's test), we conducted between-group t tests for equality of means. Where there is a significant between-group difference in variance, we report the adjusted t and p values and indicate nonequal variance. For between-group comparison of activation volumes across repeated measures at various activation thresholds we used an ANOVA and a GLM with volume (absolute or normalized) at various thresholds as within participant repeated measure, and report the relevant F and p values (see Fig. 2c,d). In testing between-group differences in the volume of control ROIs (FUS_obj, pSTS_face, and AMG_face) where the repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant between-group differences, we also used t tests and report any significant findings without correction for multiple comparisons (see Fig. 5c), biasing our results against the specificity of our findings in FFA.

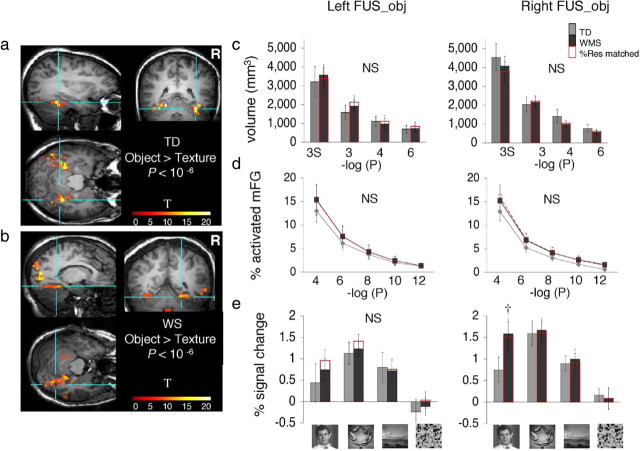

Figure 5.

Face-selective activations in the pSTS (pSTS_face). a, The pSTS_face was defined in each participant as a cluster of contiguous face-selective voxels with activation peaking in the pSTS (faces > objects, p < 10−6, uncorrected). Blue lines point to the right pSTS_face in coronal, sagittal and horizontal views from a representative TD participant. Color bar shows t values. b, Same as a but from a representative WS participant. c, Bars show the volume of the pSTS_face defined as a contiguous cluster of activation (faces > objects) peaking in the pSTS plotted as in Figure 2c. Error bars show group SEM. The volume of pSTS_face was significantly smaller in WS than in TD controls only for the spatially smoothed data defined at the threshold of p < 10−3 noted as 3s (†p < 0.05, one-tailed t test, not corrected for repeated comparisons). d, For each participant, the percentage of face-selective activation (faces > objects) for the anatomically defined left or right pSTS was calculated and plotted as in Figure 2d. There were no significant (NS) between-group differences. e, Responses from the pSTS_face (faces > objects, p < 10−4, uncorrected) to visual stimuli are plotted as in Figure 2e. Red bars, WS matched to TD participants for %Res in pSTS. Response amplitudes to visual stimuli were not significantly different among groups and there were no significant group-by-category interactions. Note that the response magnitudes are not independent of the data used to select the pSTS_face. Error bars show group SEM.

For between-group comparisons of BOLD responses to the various image categories within ROIs we used a GLM, with responses across categories as the within participant repeated measure and report the relevant F and p values (see Figs. 2e, 3d,e). Where we found a significant interaction between the factors of group and stimulus type, we used subsequent t tests to determine which stimulus types were significantly different between-groups (see Figs. 3d, 4e, 6e).

Figure 4.

Object-selective activations in the mid-fusiform gyrus (FUS_obj). a, The FUS_obj was defined in each participant as a cluster of contiguous object-selective voxels with activation peaking in the mid-fusiform gyrus (objects > textures, p < 10−6, uncorrected). Blue lines point to the right FUS_obj in coronal, sagittal, and horizontal views from a representative TD participant. Color bar indicates t values. b, Same as a but from a representative WS participant. c, Bars show the volume of the FUS_obj, defined as a contiguous cluster of object-selective activation (objects > textures) peaking in the mid-fusiform gyrus (mFG) plotted as in Figure 2c. Error bars show group SEM. There were no significant (NS) between-group differences. d, For each participant, the percentage of object-selective activation (objects > textures) in the mid-fusiform was calculated and plotted as in Figure 2d. Error bars show group SEM. e, Responses from the FUS_obj (objects > textures, p < 10−4, uncorrected) to visual stimuli are plotted as in Figure 2e. In the right hemisphere, there was a significant group-by-category interaction (p < 0.04, F test, ANOVA) due to significantly higher response magnitudes to faces in WS than in TD participants (†p < 0.04, one-tailed t test). Note that the response magnitudes are not independent of the data used to select FUS_obj. Error bars show group SEM.

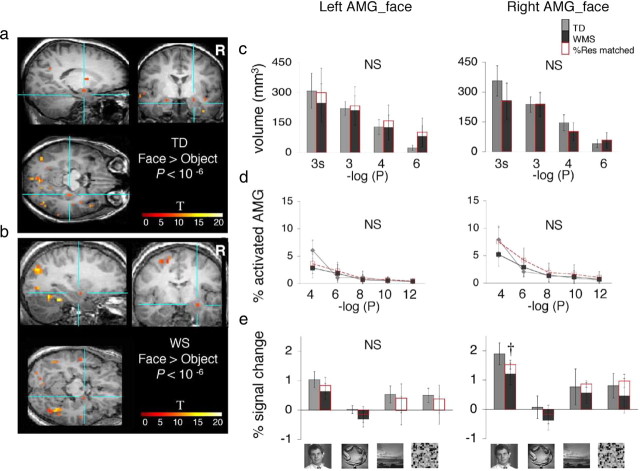

Figure 6.

Face-selective activations in the amygdala. a, The AMG_face was defined in each participant as a cluster of contiguous face-selective voxels within the anatomical boundaries of the amygdala (faces > objects, p < 10−6, uncorrected). Blue lines point to the right AMG_face in coronal, sagittal, and horizontal views from a representative TD participant. Color bar shows t values. b, Same as a but from a representative WS participant. c, Bars show the volume of the AMG_face defined as a contiguous cluster of activation (faces > objects) peaking in the amygdala plotted as in Figure 2c. There were no significant (NS) between-group differences. Error bars show group SEM. d, For each participant, the percentage of face-selective activation (faces > objects) for the anatomically defined left or right amygdala was calculated and plotted as in Figure 2d. e, Responses from the AMG_face (faces > objects, p < 10−4, uncorrected) to visual stimuli are plotted as in Figure 2e. Red bars, WS matched to TD participants for %Res in amygdala. Error bars show group SEM. In the right hemisphere, response amplitudes to faces were significantly lower among WS than TD controls (†p < 0.03, one-tailed t test). Note that the response magnitudes are not independent of the data used to select the AMG_face.

All t and F tests are based on two-tailed comparisons and equal variance across groups unless otherwise noted. For between-group comparisons of the volume of the functional ROIs, participants who showed no activations fulfilling the definition of the particular functional ROI were assigned zero for the volume of the ROI and included in the analysis. However, for between-group comparison of the responses within functionally defined ROIs, only participants who showed activations fulfilling the definition of the functional ROI were included in the analysis.

Results

Larger FFA in WS than TD

We compared the volume of the FFA in WS and TD participants, given the role of the FFA in face recognition among TD participants (Druzgal and D'Esposito, 2001; Golby et al., 2001; Ranganath et al., 2004; Nichols et al., 2006) and the growth of FFA volume during typical development of face-recognition among children (Golarai et al., 2007). Thus, we defined the FFA in each participant as a contiguous cluster of voxels that responded more to faces than to objects (p < 10−4, uncorrected) with the activation peaking in the fusiform gyrus (Fig. 2a,b). The FFA was detected in all WS and TD participants in both hemispheres. The volume of the FFA was larger in absolute terms in WS than in TD participants in both hemispheres [right FFA (rFFA), t(24) = 2.18, p = 0.04; left FFA (lFFA), t(24) = 2.10, p = 0.05] (Fig. 2c). The average rFFA volume was approximately two times larger in WS than in TD participants, whereas the average lFFA volume was 2.5 times larger among the WS participants than in TD participants.

In contrast to the larger FFA volume in WS, the anatomical volume of FUS was smaller in WS than in TD participants (Fig. 3a–c), consistent with previous reports (Reiss et al., 2004). Thus, the proportional volume of the FFA relative to the anatomical volume of the FUS gray matter was also significantly higher in WS than in TD participants (right, t(24) = 2.45, p = 0.04; left, t(24) = 2.72, p = 0.01; data not shown).

We considered whether the between-group differences in FFA volume might be influenced by any between-group differences in the level of %Res (Golarai et al., 2007; Grill-Spector et al., 2008). Therefore, we compared the FFA volumes across the subset of participants who were group-matched for their average %Res within the FUS (see Materials and Methods). In this subset of %Res-matched participants, FFA volumes were also significantly larger in WS than in TD (rFFA, t(21) = 3.18, p < 0.005; lFFA, t(21) = 2.94, p < 0.02; nonequal variance t test) (Fig. 3c). Thus, the larger FFA volume in the WS participants was independent of BOLD-related noise and goodness of GLM fit.

Next, we asked whether the variation in the absolute volume of the FFA within each group was correlated with the anatomical volume of the FUS, its gray matter content, or the subject's IQ or age. Among WS participants (or the %Res-matched subgroup), the absolute volume of the right or left FFA was not significantly correlated with the total tissue (gray and white) or gray matter volumes of the FUS anatomical ROIs. Similarly, among the TD participants there was no significant correlation between FFA volumes and FUS volumes (p > 0.40). Thus, the volume of the anatomical ROI of FUS did not explain the size of the FFA among the WS or TD groups. Likewise, variations in age (p > 0.4) or IQ measures (p > 0.3) did not predict the size of the FFA among the WS or TD participants (p > 0.40).

Does the larger FFA in WS depend on statistical threshold, clustering, or spatial smoothing?

The size of a functional ROI depends on the choice of statistical threshold that is applied to the activation map. Therefore, we asked whether the larger FFA volume in WS might depend on the statistical threshold used in defining the FFA. In each participant we defined the FFA as a contiguous cluster of voxels that responded more to faces than to objects at two additional thresholds (p < 10−3 and p < 10−6, uncorrected) with the activation peaking in the fusiform gyrus. As expected, there was a significant effect of threshold on the ROI volumes (rFFA, F(2,24) = 57.45, p < 0.0001; lFFA, F(2,24) = 18.50, p = 0.0001; repeated-measures ANOVA). Nonetheless, FFA volume was significantly larger in WS than in TD bilaterally (main effect of group across the three thresholds tested, rFFA, F(1,24) = 3.77, p = 0.032, one-tailed; %Res matched, F(1,20) = 10.16, p < 0.005; lFFA, F(1,24) = 3.76, p < 0.032, one-tailed; %Res matched, F(1,19) = 9.16, p < 0.007; repeated-measures ANOVA) (Fig. 2c), and there was no group-by-threshold interactions for the FFA volume (rFFA, F(1,40) = 0.60, p = 0.45; lFFA, F(1,50) = 1.20, p = 0.29; repeated-measures ANOVA). Thus, FFA volume was consistently larger in WS compared with TD, regardless of threshold.

Spatial smoothing of activation maps also influences the detectability of functionally defined ROIs as it is thought to reduce uncorrelated noise and enhance identification of activations. To test such effects on our results, we spatially smoothed each subject's data with a 6 mm kernel and then individually defined the FFA (see Materials and Methods) (faces > objects, 10−3). As expected, FFA volumes were larger for both groups after spatial smoothing (Fig. 2c). Nonetheless, the volume of the FFA after smoothing was also significantly greater in WS than in TD participants (rFFA, t(24) = 1.81, p = 0.04, one-tailed t test; %Res matched, t(20) = 1.83, p = 0.04, one-tailed t test; lFFA, t(24) = 1.89, p < 0.03, one-tailed t test; %Res matched, t(21) = 1.94, p < 0.04, one-tailed t test; nonequal variance) (Fig. 2c). Thus, the larger FFA in WS was insensitive to spatial smoothing.

To examine the spatial extent of face selectivity in the FUS, independent of spatial clustering and taking into consideration the anatomical volume of the fusiform gyrus in each participant, we examined the proportional extent of face-selective activations. Thus, we measured the total number of face-selective voxels in the FUS, regardless of contiguity, at five different thresholds (10−4 ≥ p ≥ 10−12, uncorrected), and divided in each individual the total activation volume by the volume of the anatomical ROI of FUS (see Materials and Methods). Consistent with the larger size of the FFA in WS, the proportional volume of face-selective activations relative to the volume of the FUS was significantly higher in WS than in TD across the various thresholds tested in both hemispheres (right, F(1,24) = 3.75, p < 0.03, one-tailed; left, F(1,24) = 3.22, p < 0.04, repeated-measures ANOVA) (Fig. 2d). Results were similar for the subset of WS participants, who were matched with TD participants by %Res in the FUS (right, F(1,20) = 4.83, p < 0.04; left, F(1,21) = 7.60, p < 0.013, repeated-measures ANOVA) (Fig. 2d). Thus, regardless of spatial contiguity, a larger proportional volume of the FUS was face-selective in WS than in TD.

FFA response amplitudes

We asked whether the larger FFA in WS participants differed from the FFA in TD participants in terms of its response amplitudes to visual stimulus categories (faces, objects, places, and textures). However, there were no significant between-group differences in response amplitudes (rFFA, F(1,24) = 0.94, p = 0.34; lFFA, F(1,24) = 1.28, p = 0.27) or group-by-stimulus-category interactions (rFFA, F(1,75) = 0.02, p = 0.89; lFFA, F(1,75) = 0.39, p = 0.53) when all participants were included. Results were similar for the subset of %Res-matched participants (p > 0.2) (Fig. 2e). Similarly, there were no between-group differences in the face-selectivity index within the FFA (p > 0.3, data not shown). This similarity in FFA responses among WS and TD participants is consistent with the uniform functional definition of the FFA across the two groups, and further confirms that the larger FFA in WS participants is not merely reflecting noisy activations. We found similar results across a series of concentric constant-size ROIs that were centered on the peak of the rFFA in each subject (supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

We also measured BOLD responses to visual stimuli across the entire anatomical ROI of FUS. This allowed an independent measurement of BOLD signals where all voxels within the anatomical ROI were included regardless of their response or selectivity (Baker et al., 2007; Vul et al., 2009). Overall response amplitudes to visual stimuli showed no between-group differences in the right or left FUS (p > 0.7, repeated-measures ANOVA). However, in the right FUS there was a significant group-by-stimulus category interaction (F(3,24) = 5.66, p = 0.002), as the response to faces were significantly higher in WS than in TD participants (p = 0.05, one-tailed t test) (Fig. 3d). Importantly, the average selectivity for faces relative to nonface stimuli (objects, places, or scrambled images) was significantly higher in the right FUS (rFUS) of WS participants compared with TD participants (F(1,24) = 6.89, p = 0.015, repeated-measures ANOVA) (Fig. 3e). This higher face selectivity in rFUS is consistent with the larger rFFA and higher proportional face-selective activations in the rFUS of WS participants that we report above (Fig. 2b,c). In contrast, average face selectivity in the left FUS was not significantly different across groups, suggesting that enlargement of the lFFA was not sufficient to dominate the FUS responses that were averaged across face and nonface selective voxels outside the FFA.

No between-group differences in the volume of FUS_obj

We tested the possibility that the larger FFA volume among WS participants might reflect a general property of the mid-fusiform gyrus in WS, independent of the type of visual stimulus. Thus, we asked whether object-selective activations in the FUS were also more extensive in WS than in TD participants. In each participant we defined an object-selective ROI as a contiguous cluster of voxels that responded more to objects than to textures at several statistical thresholds (FUS_obj, p < 10−3, 10−4, 10−6, uncorrected), with the activation peaking in the fusiform gyrus (Fig. 4a,b). At the threshold of 10−4, the FUS_obj was detected in all WS participants in both hemispheres (n = 13 of 13 participants) and in most TD participants [right FUS_obj (rFUS_obj), 13 of 13 participants; left FUS_obj (lFUS_obj), 12 of 13 participants]. There were no between-group differences in the volume of the FUS_obj at any of the three thresholds tested or after spatial smoothing of the data (rFUS_obj, F(1,24) = 0.02, p = 0.9; %Res matched, F(1,20) = 0.08, p = 0.8; lFUS_obj, F(1,24) = 0.06, p = 0.82; %Res matched, F(1,21) = 0.008, p = 0.93) (Fig. 4c). Thus, in contrast to the larger FFA in WS, the spatial extent of an object-selective region in the fusiform gyrus was not different between groups.

We also examined the relative spatial extent of FUS object-selective activations regardless of spatial contiguity by counting the number of object-selective voxels (regardless of contiguity) relative to the volume of the FUS at five different thresholds (object > textures, 10−4 ≥ p ≥ 10−12, uncorrected) (see Materials and Methods). The proportional volume of object-selective activations relative to the volume of FUS was not statistically different among WS and TD participants (rFUS_obj, F(1,24) = 0.03, p = 0.9; %Res matched, F(1,20) = 0.08, p = 0.8; lFUS_obj, F(1,24) = 0.38, p = 0.54; %Res matched, F(1,21) = 0.35, p = 0.56) (Fig. 4d). In sum, there were no between-group differences in the absolute or relative volume of object-selective activations in the FUS, regardless of how we defined the functional ROIs. Thus, the larger volume of face-selective activations in the FUS cannot be explained by a general property of the FUS that would be uniformly evident for faces and objects.

Response amplitudes across object-selective ROIs

Next, we measured the response amplitudes within the object-selective ROI in the fusiform gyrus (FUS_obj). In the right FUS_obj (objects > textures, p = 10−4, uncorrected), the overall responses to visual stimuli were not significantly different across groups (F(1,24) = 0.62, p = 0.40; %Res matched, F(1,20) = 0.83, p = 0.37). However, there was a significant group-by-stimulus-type interaction (F(1,75) = 8.09, p < 0.01; %Res matched, F(1,60) = 5.45, p < 0.03), due to significantly higher response amplitudes to faces in WS than in TD participants (t(24) = 1.91, p < 0.03, one-tailed t test; %Res matched, t(20) = 1.83, p < 0.04, one-tailed t test) (Fig. 4e). Given that the FUS_obj and FFA often overlap (Grill-Spector et al., 2001), this result is consistent with our finding of larger FFAs and higher face selectivity in the right anatomical ROI of FUS in WS.

In the left FUS_Obj, there were no between-group differences in responses to stimulus types (F(1,24) = 0.10, p = 0.75; group × stimulus type, F(1,75) = 0.63, p = 0.44; %Res matched, F(1,21) = 0.40, p = 0.54; group × stimulus type, F(1,69) = 0.94, p = 0.35) (Fig. 4e), consistent with the similar face selectivity in the left FUS ROIs among WS and TD participants (see Fig. 3e).

Face-selective activations in STS and amygdala are not greater in WS compared with TD participants

We asked whether FFA enlargement in WS participants was regionally specific to the fusiform gyrus, or represented a more widespread enhancement in face-specific responses that might be observed across multiple brain regions with face-selective responses. Thus, we repeated our analyses in two other face-selective regions, one along the posterior aspect of the ascending limb of the STS (pSTS_face) and another in the amygdala (AMG_face). We chose to examine these regions, motivated by their key roles in processing socially communicative facial information (McCarthy et al., 1994; Puce et al., 1998; Allison et al., 2000; Puce and Perrett, 2003; Thompson et al., 2007), the characteristic hypersociability in WS (Bellugi et al., 2000, 2007; Jones et al., 2000; Järvinen-Pasley et al., 2008), and reports of structural and functional alterations of the amygdala in WS (Golden et al., 1995; Galaburda et al., 2003; Mobbs et al., 2004; Reiss et al., 2004; Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2005; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2006; Porter et al., 2007; Sarpal et al., 2008; Young et al., 2008; Haas et al., 2009, Paul et al., 2009). However, we found no between-group differences in the volume of face-selective activations in the pSTS (Fig. 5) or amygdala (Fig. 6), despite some trends toward smaller volumes of the right pSTS at a specific threshold (Fig. 5c) and a significantly lower response to faces in the right amygdala (Fig. 6e) among WS participants, contrasting our findings in the FFA and suggesting the specificity of the latter results.

Larger FFA volume is associated with normal levels of face recognition performance in WS

To relate our fMRI measures to previous reports of preserved face-recognition performance (Bellugi et al., 2000), we examined WS and TD participants' performance outside the scanner on a standard Benton recognition test. There were no between-group differences in Benton test performance (Table 1), consistent with previous reports (Bellugi et al., 2000). However, there was a significantly positive correlation between rFFA size and performance scores on the Benton test among a subset of WS participants that were matched to the TD group on %Res (Table 2). This correlation was significant regardless of the statistical threshold used for defining the rFFA (Benton performance vs rFFA volumes defined at various thresholds of p = 10−3, 10−4, and 10−6) (Table 2, Fig. 7b), and also when performing this analysis on a larger subset of WS subjects only excluding the two WS participants with the highest %Res (Benton performance vs rFFA volumes defined at thresholds of p = 10−3 of 10 −4; 0.37 < r < 0.92, 0.0001 < p < 0.26, n = 11) (Fig. 7b). However, this correlation did not reach statistical significance when the two WS participants with the noisiest fMRI data were included, perhaps due to an underestimation of their rFFA volume resulting from BOLD-related noise (Table 2, Fig. 7b).

Table 2.

Correlations between rFFA size (at three thresholds), Benton face recognition, and age

| Age | Intelligence test (WAIS-III or WAIS-R) |

BUP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ_FS | IQ_P | IQ_V | |||

| WS participants | |||||

| rFFA | −0.2 < r < −0.1 | 0.0 < r < 0.2 | −0.10 < r < 0.1 | −0.1 < r < 0.1 | 0.08 < r < 0.4 |

| n = 13 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | |

| BUP | r = 0.05 | r = 0.5 * | r = 0.5 | r = 0.4 | |

| n = 13 | n = 12 | n = 12 | n = 12 | – | |

| WS participants matched on %Res to TD participants | |||||

| rFFA | −0.1 < r < 0.1 | −0.3 < r < −0.0 | −0.1 < r < −0.3 | −0.2 < r < 0.0 | 0.7 < r < 0.9† |

| n = 8 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | N = 8 | |

| BUP | r = 0.01 | r = 0.4* | r = 0.3* | r = 0.5 | |

| n = 8 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | – | |

| TD participants | |||||

| rFFA | −0.1 < r < 0.3 | −0.4 < r < −0.1 | −0.4 < r < 0.1 | −0.4 < r < −0.1 | 0.3 < r < 0.5 |

| n = 8 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 10 | N = 8 | |

| BUP | r = −0.1 | r = 0.0 | r = −0.1 | r = 0.1 | |

| n = 8 | n = 8 | n = 8 | n = 8 | – | |

IQ_FS, Overall IQ scores, IQ_P, performance IQ; IQ_V, verbal IQ; BUP, Benton face recognition. All scores are reported as mean ± SD.

*p < 0.05, one-tailed t test; **p < 0.05, one-tailed t test; †0.007 < p < 0.05, two-tailed t test.

In contrast to the WS participants, the correlation between rFFA volume (defined at any of the thresholds) and Benton scores did not reach statistical significance among TD participants (Table 2, Fig. 7a). This is consistent with a previous report on TD adults using a recognition memory task (Golarai et al., 2007), which found no relationship between rFFA size and face-recognition memory performance among typically matured participants. Alternatively, it might reflect a potentially insufficient sensitivity of the Benton test in capturing subtle variations in face-processing ability among TD adults (Duchaine and Nakayama, 2004).

To test the regional specificity of the correlation between Benton performance and rFFA size, we examined the correlation between Benton performance and the size of other functionally defined ROIs in WS participants. In contrast to the rFFA, the volume of the lFFA in WS (or in a %Res-matched subset of participants) was not correlated with performance on Benton (p > 0.44). Similarly, among WS participants (or a %Res-matched subset of participants), there were no significant correlations between Benton performance and volume of other functionally defined cluster ROIs at any of the thresholds tested (FUS_obj, pSTS_face, or AMG_face volumes defined at thresholds of p = 10−3, 10−4, or10−6 vs Benton performance, p > 0.3) (data not shown), suggesting the specificity of the relationship between rFFA volume and proficiency in the Benton upright face recognition task among %Res-matched WS participants.

WS participants' scores on measures of general intelligence were significantly lower than those of the TD participants (Table 1), consistent with previous reports on moderate intellectual deficits in WS (Bellugi et al., 2000). Thus, we tested whether general cognitive ability predicted Benton performance in WS participants. Benton scores were positively correlated with measures of overall IQ and P_IQ in WS participants (Table 2). Nevertheless, the correlation between rFFA size and Benton performance remained significant among the %Res-matched WS participants (at all three thresholds for cluster ROIs) after controlling for IQ (r > 0.68, p < 0.04, one-tailed test). In contrast, there were no correlations between Benton scores in WS with age (p > 0.6). Thus, Benton performance in WS was independently correlated with measures of IQ and rFFA size but not with participants' age.

Discussion

We found evidence for enhanced responsiveness to faces in the fusiform gyrus of adults diagnosed with WS compared with age-matched TD participants. This enhancement manifested as larger FFAs that were approximately twice the absolute volume of TD participants', despite the smaller size of the anatomical region of fusiform gyrus in WS. Furthermore, the larger FFA volume was associated with apparently normal performance levels on the Benton recognition test outside the scanner and with similar levels of FFA responses to faces among TD and WS. These findings were specific to face-selective responses in the fusiform gyrus, as there were no between-group differences in the activation volumes for objects in the FUS or for faces in the pSTS or amygdala. To our knowledge, this is the first detailed report of larger FFA volume in WS compared with TD participants, suggesting that the apparently normal face-recognition performance in WS is associated with atypically large FFA volume.

We controlled for several methodological factors that might confound comparison of fMRI results among WS and TD participants. First, we based our functional analyses on individually defined ROIs without spatial normalization. WS is associated with smaller overall brain size and gray matter volume compared with TD, with notable variations across brain regions, and between-group differences in regional brain shape and gyrification (Schmitt et al., 2001; Reiss et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2005). Therefore, this ROI approach was essential in avoiding potential confounds associated with conventional group analyses involving spatial normalization of data to a standardized brain template (Eckert et al., 2006). Second, we examined an inclusive measure of BOLD-related noise (i.e., %Res) from every anatomical ROI to control for any spurious activations due to motion or noisier BOLD signals in WS (Golarai et al., 2007; Grill-Spector et al., 2008). Given the higher %Res in WS, we reanalyzed our data and found similar results in subsets of WS participants that were matched to TD on local %Res. Third, we found consistent results across a range of thresholds on statistical maps. These methodological controls confirmed the reliability of our findings.

We asked whether the larger FFA reflected a general property of the fusiform gyrus in WS and examined an object-selective region in the fusiform gyrus (FUS_obj) that partially overlaps the FFA among TD participants (Grill-Spector et al., 2001; Golarai et al., 2007). We found no between-group differences in FUS_obj volume, confirming the specificity of our findings in the FFA, and ruling out substantial contributions by metabolic, vascular, or anatomical anomalies in the fusiform gyrus of WS. Instead, FUS_obj responses to faces (but not to other visual stimuli) were higher among WS participants compared with TD participants, suggesting a greater spatial overlap between FUS_obj and the FFA in WS, consistent with a larger FFA size in WS. Similarly, face selectivity in the entire right fusiform gyrus (defined anatomically) was higher in WS compared with TD participants, also consistent with a larger right FFA in WS.

Next, we asked whether the larger FFA in WS reflected a general hyper-responsiveness to faces, also evident in other face-selective regions such as the STS and the amygdala. Given the hypersociability in WS, we expected that any general tendency toward altered face responsiveness would likely manifest in these regions, which are involved in processing socially relevant facial information in TD individuals (McCarthy et al., 1994; Puce et al., 1998; Allison et al., 2000; Puce and Perrett, 2003; Thompson et al., 2007). Furthermore, WS is associated with atypical structure and function of the amygdala (Golden et al., 1995; Galaburda et al., 2003; Mobbs et al., 2004; Reiss et al., 2004; Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2005; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2006; Porter et al., 2007; Sarpal et al., 2008; Young et al., 2008; Haas et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2009). However, we found no between-group differences in the pSTS or amygdala, supporting the specificity of the larger FFA volume in WS. These findings do not preclude atypical amygdala or pSTS responses to other stimuli or tasks more specifically tailored to these regions' specialization in processing emotions, intentions, and gaze. Individuals with WS misinterpret facial expressions (Adolphs et al., 2002), despite proficiency at recognizing facial identity (Bellugi et al., 2000). However, our results suggest that any contributions of attentional processes or viewing strategies among WS participants in our experiment would have to be selectively directed to the FFA to explain our findings.

Previous fMRI studies of face processing in WS either did not examine or found no differences between WS and TD participants in the volume of the fusiform gyrus responses to faces (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2004; Mobbs et al., 2004; Sarpal et al., 2008), although one study reported higher amplitude response to faces (compared with textures) in some regions of the fusiform gyrus among participants with WS (Paul et al., 2009), consistent with our findings of higher face selectivity in the fusiform gyrus in this group. However, these studies used group-analysis methods that are less sensitive to between-group differences in the spatial extent of activations than the individually defined ROI methods used here. Furthermore, most of these studies did not specifically examine face- or object-selective regions in the fusiform gyrus and instead contrasted attention to face identity relative to face location (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2004), viewing faces relative to places (Sarpal et al., 2008), or low-level texture stimuli (Mobbs et al., 2004; Paul et al., 2009), which activates a constellation of ventral stream regions. Regions defined from these contrasts are expected to be larger and less face-selective and to include both the FFA and the FUS_obj. Given our finding of similar FUS_obj volumes in WS and TD, inclusion of the FUS_obj could diminish the likelihood of FFA volume differences in these studies. Finally, previous studies did not compare the volume of activations or response profiles to faces or nonfaces across multiple brain regions in WS.

The atypically large FFA volume that we found in WS was positively correlated with apparently normal performance levels on a standardized face-identity recognition task (Benton test) in the same participants. This finding is analogous to electrophysiological reports of atypically large N200 in WS, which is correlated with performance on the Benton test (Mills et al., 2000). However, in our experiments, the correlation between rFFA size and Benton scores reached statistical significance only after excluding two WS participants with the noisiest BOLD signals. The similarity in the mean performance across TD and WS in the Benton test may be due to insufficient sensitivity of the Benton test in detecting subtle variations in face-recognition proficiency (Duchaine and Nakayama, 2004). Nevertheless, the similar performance levels on the Benton test among our WS participants and previous publications suggest that our findings are not due to an atypical sample of WS participants in our study. Instead, our findings reveal substantially larger volume of FFA than was previously undetected, perhaps due to methodological limitations. Thus, full elucidation of the atypical aspects of face processing and the behavioral consequences of the larger FFA in WS will require future application of more sensitive behavioral measures in combination with simultaneous fMRI.

Are there causal connections between rFFA size and face recognition proficiency in WS (or in TD) patients? Although our data do not directly address this question, they raise several intriguing possibilities. One possibility is that heightened attention to faces and atypical patterns of face viewing lead to enhanced instantaneous face responses in the fusiform gyrus as well as face recognition proficiency in WS. Our fMRI findings indicate that the contribution of such viewing and attentional effects in WS would have to be specifically directed to the fusiform gyrus, as the pSTS and amygdala responses to faces were not enhanced. A second possibility is that the larger FFA volume in WS reflects functional reorganization of the fusiform gyrus as a developmental endpoint of atypical visual experience with faces, given that FFA volume undergoes a prolonged growth during normal development (Golarai et al., 2007). Greater cumulative visual experience with faces during development might lead to regional increases in the number and/or selectivity of face-responsive neurons (Grill-Spector et al., 2008), as well as changes at the synaptic level in the fusiform gyrus of WS, manifesting as a larger FFA and supporting face-recognition proficiency. Similar experience-dependent expansions of cortical representations were reported in human models of plasticity (Merzenich et al., 1996; Weisberg et al., 2007). A third possibility is that genetic factors underlie FFA's larger volume in WS. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive and require further investigation with longitudinal studies of young children with WS, which could also substantially contribute to our understanding of mechanisms of cortical specialization during normal and atypical development.

In sum, we found evidence for atypically large FFA volume in adult WS. Our findings form a basis for better understanding the role of the FFA in WS. Future studies are needed to determine the functional consequences of FFA size in face processing, to specify which deleted genes in WS contribute to FFA size and face processing in TDs, and to indicate whether our findings in the FFA are related to additional changes in the visual cortex in WS.

Footnotes

This research was supported by U.S. National Institute of Health Grants NICHD 5P01HD033113 (to A.M.G., D.L.M., U.B., and A.L.R.) and 3R01HD049653 (to A.L.R.), Klingenstein Fellowship Grants NSF BCS-0617688 and NEI1R21EY017741 (to K.G.S.), and National Institute of Mental Health Fellowship 5T32MH019908 (to G.G.). We thank Asya Karchemskiy for conducting fMRI and for help with anatomical measures, Adam Tenforde and Derek Cheuk-Ming Ng for help with fMRI, Yvonne Searcy for behavioral measures, Paul Mazaika and Dara Ghahremani for software support, and Anders Greenwood and Nathan Witthoft for helpful comments on the manuscript. G.G. contributed to study implementation, image processing/data analysis, and manuscript preparation/revision; K.G.S. contributed to study design, image processing/data analysis, and manuscript preparation/revision; A.L.R. contributed to study design, study implementation, image processing/data analysis, and manuscript preparation/revision; S.H. and B.H. contributed to image processing/data analysis; and A.M.G., D.L.M., and U.B. contributed to study design and manuscript preparation/revision.

References

- Adolphs R, Baron-Cohen S, Tranel D. Impaired recognition of social emotions following amygdala damage. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:1264–1274. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, Puce A, McCarthy G. Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4:267–278. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CI, Hutchison TL, Kanwisher N. Does the fusiform face area contain subregions highly selective for nonfaces? Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:3–4. doi: 10.1038/nn0107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellugi U, Lichtenberger L, Jones W, Lai Z, St George M. I. The neurocognitive profile of Williams syndrome: a complex pattern of strengths and weaknesses. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(Suppl 1):7–29. doi: 10.1162/089892900561959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellugi U, Järvinen-Pasley A, Doyle T, Reilly J, Korenberg JR. Affect, social behavior and brain in Williams syndrome. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Sivan AB, Hamsher Kd, Varney NR, Spreen O. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1978. Benton facial recognition. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher KdeS, Varney N, Spreen O. New York: Oxford UP; 1983. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Druzgal TJ, D'Esposito M. Activity in fusiform face area modulated as a function of working memory load. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2001;10:355–364. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchaine BC, Nakayama K. Developmental prosopagnosia and the Benton facial recognition test. Neurology. 2004;62:1219–1220. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118297.03161.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy H. The human brain. New York: Springer Wien; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert MA, Tenforde A, Galaburda AM, Bellugi U, Korenberg JR, Mills D, Reiss AL. To modulate or not to modulate: differing results in uniquely shaped Williams syndrome brains. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart AK, Morris CA, Atkinson D, Jin W, Sternes K, Spallone P, Stock AD, Leppert M, Keating MT. Hemizygosity at the elastin locus in a developmental disorder, Williams syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;5:11–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, Holinger D, Mills D, Reiss A, Korenberg JR, Bellugi U. Williams syndrome: a summary of cognitive, electrophysiological, anatomofunctional, microanatomical and genetic findings (in Spanish) Rev Neurol. 2003;36(Suppl 1):S132–S137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Law CS. Spiral-in/out BOLD fMRI for increased SNR and reduced susceptibility artifacts. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:515–522. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golarai G, Ghahremani DG, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Reiss A, Eberhardt JL, Gabrieli JD, Grill-Spector K. Differential development of high-level visual cortex correlates with category-specific recognition memory. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:512–522. doi: 10.1038/nn1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golby AJ, Gabrieli JD, Chiao JY, Eberhardt JL. Differential responses in the fusiform region to same-race and other-race faces. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:845–850. doi: 10.1038/90565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden JA, Nielsen GP, Pober BR, Hyman BT. The neuropathology of Williams syndrome: report of a 35-year-old man with presenile beta/A4 amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:209–212. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540260115030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Kourtzi Z, Kanwisher N. The lateral occipital complex and its role in object recognition. Vision Res. 2001;41:1409–1422. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Knouf N, Kanwisher N. The fusiform face area subserves face perception, not generic within-category identification. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:555–562. doi: 10.1038/nn1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Golarai G, Gabrieli J. Developmental neuroimaging of the human ventral visual cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BW, Mills D, Yam A, Hoeft F, Bellugi U, Reiss A. Genetic influences on sociability: heightened amygdala reactivity and event-related responses to positive social stimuli in Williams syndrome. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1132–1139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5324-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier LW, Fulton RS, Fulton LA, Graves TA, Pepin KH, Wagner-McPherson C, Layman D, Maas J, Jaeger S, Walker R, Wylie K, Sekhon M, Becker MC, O'Laughlin MD, Schaller ME, Fewell GA, Delehaunty KD, Miner TL, Nash WE, Cordes M, et al. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 7. Nature. 2003;424:157–164. doi: 10.1038/nature01782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen-Pasley A, Bellugi U, Reilly J, Mills DL, Galaburda A, Reiss AL, Korenberg JR. Defining the social phenotype in Williams syndrome: a model for linking gene, the brain, and behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:1–35. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W, Bellugi U, Lai Z, Chiles M, Reilly J, Lincoln A, Adolphs R. II. Hypersociability in Williams syndrome. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(Suppl 1):30–46. doi: 10.1162/089892900561968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A, Thomas M, Annaz D, Humphreys K, Ewing S, Brace N, Duuren M, Pike G, Grice S, Campbell R. Exploring the Williams syndrome face-processing debate: the importance of building developmental trajectories. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1258–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenberg JR, Chen XN, Hirota H, Lai Z, Bellugi U, Burian D, Roe B, Matsuoka R. VI. Genome structure and cognitive map of Williams syndrome. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(Suppl 1):89–107. doi: 10.1162/089892900562002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy G, Blamire AM, Puce A, Nobre AC, Bloch G, Hyder F, Goldman-Rakic P, Shulman RG. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of human prefrontal cortex activation during a spatial working memory task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8690–8694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Klein BP, Bertrand J, Kwitny S, Appelbaum LG. Attention to faces in infancy: comparison of an infant with Williams syndrome to typically developing infants. Infant Behav Dev. 1998;21(Suppl 1):571. [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich M, Wright B, Jenkins W, Xerri C, Byl N, Miller S, Tallal P. Cortical plasticity underlying perceptual, motor, and cognitive skill development: implications for neurorehabilitation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kohn P, Mervis CB, Kippenhan JS, Olsen RK, Morris CA, Berman KF. Neural basis of genetically determined visuospatial construction deficit in Williams syndrome. Neuron. 2004;43:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Hariri AR, Munoz KE, Mervis CB, Mattay VS, Morris CA, Berman KF. Neural correlates of genetically abnormal social cognition in Williams syndrome. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:991–993. doi: 10.1038/nn1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills DL, Alvarez TD, St George M, Appelbaum LG, Bellugi U, Neville H. III. Electrophysiological studies of face processing in Williams syndrome. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(Suppl 1):47–64. doi: 10.1162/089892900561977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D, Garrett AS, Menon V, Rose FE, Bellugi U, Reiss AL. Anomalous brain activation during face and gaze processing in Williams syndrome. Neurology. 2004;62:2070–2076. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129536.95274.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D, Eckert MA, Menon V, Mills D, Korenberg J, Galaburda AM, Rose FE, Bellugi U, Reiss AL. Reduced parietal and visual cortical activation during global processing in Williams syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols EA, Kao YC, Verfaellie M, Gabrieli JD. Working memory and long-term memory for faces: evidence from fMRI and global amnesia for involvement of the medial temporal lobes. Hippocampus. 2006;16:604–616. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Kubik S, Abernathey CD. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1990. Atlas of the cerebral sulci. [Google Scholar]

- Paul BM, Snyder AZ, Haist F, Raichle ME, Bellugi U, Stiles J. Amygdala response to faces parallels social behavior in Williams syndrome. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;4:278–285. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter MA, Coltheart M, Langdon R. The neuropsychological basis of hypersociability in Williams and Down syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2839–2849. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Perrett D. Electrophysiology and brain imaging of biological motion. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:435–445. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Allison T, Bentin S, Gore JC, McCarthy G. Temporal cortex activation in humans viewing eye and mouth movements. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2188–2199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02188.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, DeGutis J, D'Esposito M. Category-specific modulation of inferior temporal activity during working memory encoding and maintenance. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;20:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss AL, Eckert MA, Rose FE, Karchemskiy A, Kesler S, Chang M, Reynolds MF, Kwon H, Galaburda A. An experiment of nature: brain anatomy parallels cognition and behavior in Williams syndrome. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5009–5015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5272-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riby D, Hancock PJ. Looking at movies and cartoons: eye-tracking evidence from Williams syndrome and autism. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009a;53:169–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riby DM, Hancock PJ. Do faces capture the attention of individuals with Williams syndrome or autism? Evidence from tracking eye movements. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009b;39:421–431. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riby DM, Doherty-Sneddon G, Bruce V. Atypical unfamiliar face processing in Williams syndrome: what can it tell us about typical familiarity effects? Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2008;13:47–58. doi: 10.1080/13546800701779206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riby DM, Doherty-Sneddon G, Bruce V. The eyes or the mouth? Feature salience and unfamiliar face processing in Williams syndrome and autism. Q J Exp Psychol (Colchester) 2009;62:189–203. doi: 10.1080/17470210701855629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio A, Sousa N, Férnandez M, Henriques M, Gonçalves OF. Memory abilities in Williams syndrome: dissociation or developmental delay hypothesis? Brain Cogn. 2008;66:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarpal D, Buchsbaum BR, Kohn PD, Kippenhan JS, Mervis CB, Morris CA, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Berman KF. A genetic model for understanding higher order visual processing: functional interactions of the ventral visual stream in Williams syndrome. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2402–2409. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt JE, Eliez S, Bellugi U, Reiss AL. Analysis of cerebral shape in Williams syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Skwerer DP, Joseph RM. Model syndromes for investigating social cognitive and affective neuroscience: a comparison of autism and Williams syndrome. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2006;1:175–182. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JC, Hardee JE, Panayiotou A, Crewther D, Puce A. Common and distinct brain activation to viewing dynamic sequences of face and hand movements. Neuroimage. 2007;37:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Lee AD, Dutton RA, Geaga JA, Hayashi KM, Eckert MA, Bellugi U, Galaburda AM, Korenberg JR, Mills DL, Toga AW, Reiss AL. Abnormal cortical complexity and thickness profiles mapped in Williams syndrome. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4146–4158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0165-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong F, Nakayama K, Vaughan JT, Kanwisher N. Binocular rivalry and visual awareness in human extrastriate cortex. Neuron. 1998;21:753–759. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari S, Carlesimo GA. Short-term memory deficits are not uniform in Down and Williams syndromes. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006;16:87–94. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vul E, Harris C, Winkielman P, Pashler H. Voodoo correlations in social neuroscience. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2009;4:274–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg J, van Turennout M, Martin A. A neural system for learning about object function. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:513–521. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam A, Searcy YM, Hill KJ, Grichanik M, Bellugi U. Face processing strength in Williams syndrome extends to memory for faces. Presented at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society Annual Meeting; April; San Francisco, CA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Young EJ, Lipina T, Tam E, Mandel A, Clapcote SJ, Bechard AR, Chambers J, Mount HT, Fletcher PJ, Roder JC, Osborne LR. Reduced fear and aggression and altered serotonin metabolism in Gtf2ird1-targeted mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]