Abstract

Purpose

The optimal time between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and surgery for rectal cancer has been debated. This study evaluated the influence of this interval on oncological outcomes.

Methods

We compared postoperative complications, pathological downstaging, disease recurrence, and survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent surgical resection <8 weeks (group A, n = 105) to those who had surgery ≥8 weeks (group B, n = 48) after neoadjuvant CRT.

Results

Of 153 patients, 117 (76.5%) were male and 36 (23.5%) were female. Mean age was 57.8 years (range, 28 to 79 years). There was no difference in the rate of sphincter preserving surgery between the two groups (group A, 82.7% vs. group B, 77.6%; P = 0.509). The longer interval group had decreased postoperative complications, although statistical significance was not reached (group A, 28.8% vs. group B, 14.3%; P = 0.068). A total of 111 (group A, 75 [71.4%] and group B, 36 [75%]) patients were downstaged and 26 (group A, 17 [16.2%] and group B, 9 [18%]) achieved pathological complete response (pCR). There was no significant difference in the pCR rate (P = 0.817). The longer interval group experienced significant improvement in the nodal (N) downstaging rate (group A, 46.7% vs. group B, 66.7%; P = 0.024). The local recurrence (P = 0.279), distant recurrence (P = 0.427), disease-free survival (P = 0.967), and overall survival (P = 0.825) rates were not significantly different.

Conclusion

It is worth delaying surgical resection for 8 weeks or more after completion of CRT as it is safe and is associated with higher nodal downstaging rates.

Keywords: Rectal neoplasm, Neoadjuvant therapy, Chemoradiotherapy, Preoperative period, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Multimodality treatment, with preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and optimal surgery including total mesorectal excision (TME) has recently been considered the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer [1-3]. This approach is associated with reduced local recurrence, increased downstaging and greater rates of sphincter preservation [3-10].

However, the optimal time between neoadjuvant CRT and surgery remains debatable. In the 1999 Lyon R90-01 trial, the only trial to randomize patients to different interval lengths, Francois et al. [11] compared short (within 2 weeks) and long (6 to 8 weeks) interval groups following preoperative radiotherapy (RT) and showed that the longer interval was associated with better clinical tumor response, pathological downstaging, and a nonsignificant trend towards increased sphincter preservation. They suggested that a long interval may increase the chance of successful sphincter-saving surgery through improved tumor response. As a consequence, this 6- to 8-week interval has become part of the standard protocol for the treatment of mid and low rectal cancer [1,12]. However, some investigators recently suggested that increased intervals could potentially increase the tumor downstaging effect because radiation-induced necrosis appears to be a time-dependent phenomenon [4]. Nevertheless, many surgeons have hesitated to delay surgery beyond 6 to 8 weeks due to concerns that radiation-induced pelvic fibrosis may increase the technical difficulty of the operation, and increase the risk of surgical complications and loco-regional recurrence [4,13]. For these reasons, we retrospectively reviewed our data, comparing the outcomes of patients who were operated on greater than or equal to 8 weeks after completion of CRT to that of patients who were operated on less than 8 weeks after CRT.

The aim of this study was to analyze the influence of the time interval from completion of neoadjuvant CRT to surgery on oncologic outcomes including tumor downstaging, complications, local and systemic recurrence, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS).

METHODS

Patient characteristics

We performed a retrospective review of a prospectively entered database on 163 consecutive patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent preoperative CRT followed by radical resection for curative intent between November 2005 and July 2009 at our department.

Of these, 10 patients were excluded; six because of prior cancer operation (three had stomach cancer, one had maxillary cancer, one had cervical cancer, and one patient had lung cancer), two patients underwent emergency operation, and two patients did not complete CRT. The remaining 153 patients were analyzed.

Staging workup was performed before preoperative CRT in all patients using a combination of physical examination including digital rectal examination, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, colonoscopy with or without rigid proctoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scanning of abdomen and pelvis, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without transrectal ultrasonography. Staging workup was repeated before surgery.

Preoperative chemoradiation therapy

All patients received neoadjuvant CRT. Preoperative radiation therapy of 45 Gy/25 fractions was delivered to the pelvis, followed by a 5.4 Gy boost to the primary tumor over a period of 5 weeks using linear accelerators with energy of 10 MV. The median radiation dose received was 5,040 cGy (96.1%). The radiation field was as follows: the upper margin was 1.5 cm above the sacral promontory (L5 level), and the lateral margin was 1.5 cm lateral to the bony pelvis to include the pelvic lymph nodes. During radiation therapy, all patients were examined on a weekly basis to evaluate toxicity. All patients received their planned radiation prescription.

Chemotherapy was administered concurrently with radiotherapy and the regimen was 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based and delivered as intravenous bolus injection of two cycles of 5-FU (425 mg/m2/day) and leucovorin (20 mg/m2/day) for 5 days during the first and fifth weeks of radiation therapy. The other chemotherapy regimens were CPT-11/S-1 (16%), TS-1/irinotecan (12%), or Xeloda (6%).

Surgical resection

Surgery was scheduled 6 to 8 weeks after the completion of CRT, but because of logistic, scheduling, and other clinical factors, the practical interval varied from 4 to 14 weeks. Surgery was performed by expert colorectal surgeons who adhered to the oncologic principals of TME with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation. Tumor mesorectal excision (TME) was introduced by Heald [14] in 1979. It advocates for sharp pelvic dissection based on pelvic anatomy under direct vision along the plane of the proper rectal fascia, resulting in en bloc removal of rectal cancer and surrounding mesorectum containing lymph nodes. All specimens were assessed grossly for the quality of TME by an expert pathologist. All specimens were identified as complete or nearly complete.

Postoperative follow-up

All patients were closely followed up by the surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists in the Colorectal Cancer Clinic at our institution. Postoperative follow-up on all patients was conducted every three months for two years. Clinical examination, measurement of serum CEA levels, and chest X-rays were performed during each follow-up. After two years, patients underwent follow-up examinations every six months. Abdominopelvic CT was first done at the sixth postoperative month and then yearly thereafter. An additional pelvic MRI was done when routine CT scan failed to discriminate suspicious lesions in the pelvic cavity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for group comparisons was performed using Pearson's χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, or Student's t-test, depending on the nature of the data. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. OS was defined as the time between surgery and death or last follow-up, and local DFS as the time to local recurrence or last follow-up. Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan-Meier estimates and the survival of the groups was compared using log-rank tests. All statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

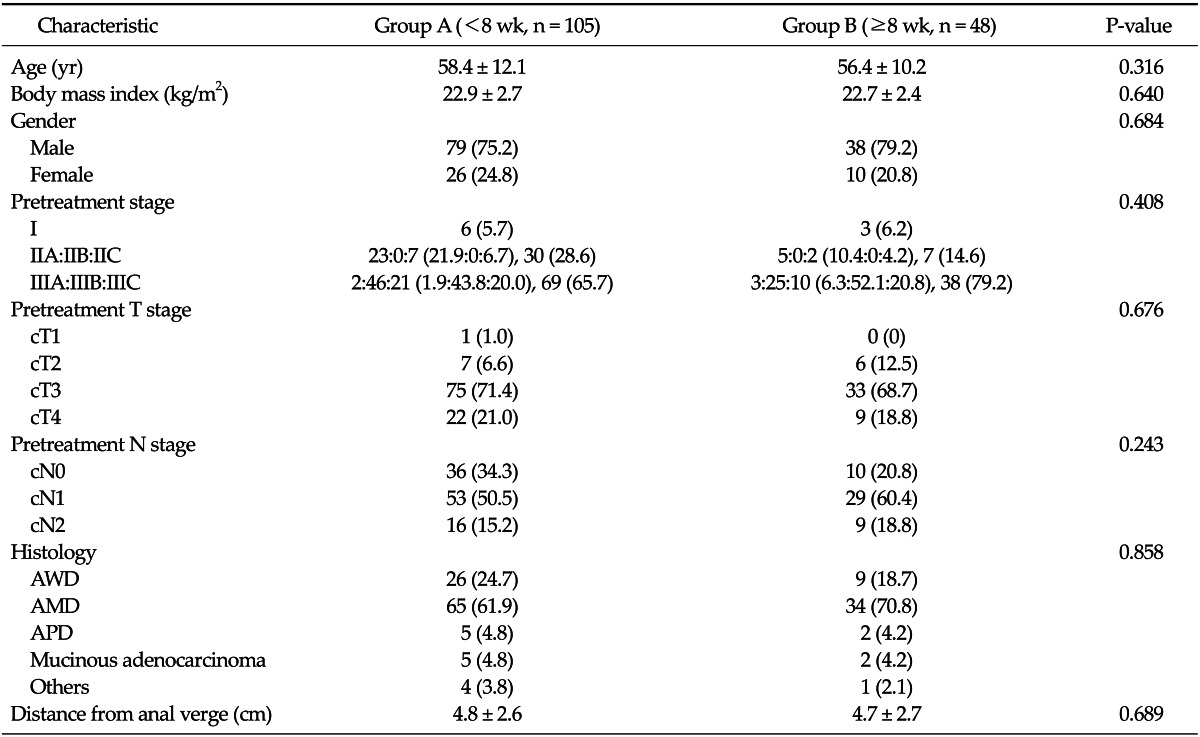

Patient and tumor characteristics

Overall, 153 patients were eligible for the study. The patient population consisted of 117 males (76.5%) and 36 females (23.5%) with mean age of 57.8 years (range, 28 to 79 years). The median body mass index was 22.83 kg/m2 (range, 16.36 to 28.96 kg/m2) and median tumor distance from the anal verge was 4.8 cm (range, 1 to 15 cm).

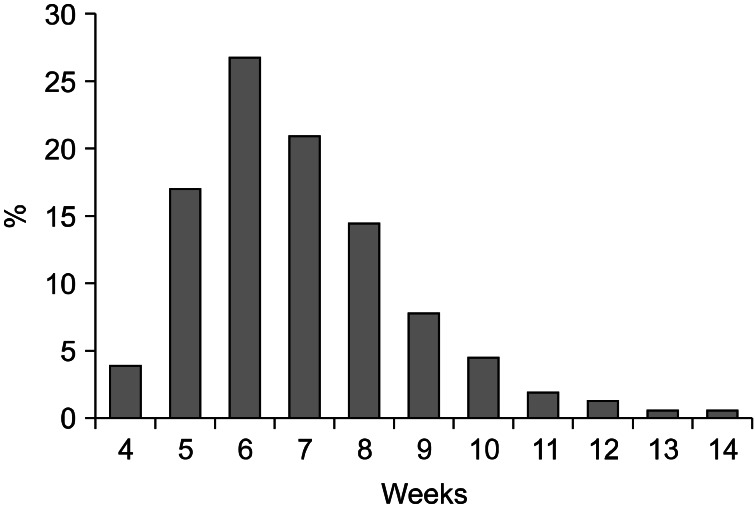

The interval from completion of chemoradiotherapy to surgery ranged from 28 to 99 days (median, 52 days) (Fig. 1). Of the 153 patients, 105 (68.6%) underwent surgery less than 8 weeks after CRT completion (group A), whereas 48 patients (31.4%) underwent surgery greater than or equal to 8 weeks after CRT (group B). The two groups did not differ in age, gender ratio, location of tumor from anal verge, or distribution of clinical T-stage and N-stage. Patient demographics and tumor characteristic are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of interval lengths.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

AWD, adenocarcinoma well differentiated; AMD, adenocarcinoma moderately differentiated; APD, adenocarcinoma poorly differentiated.

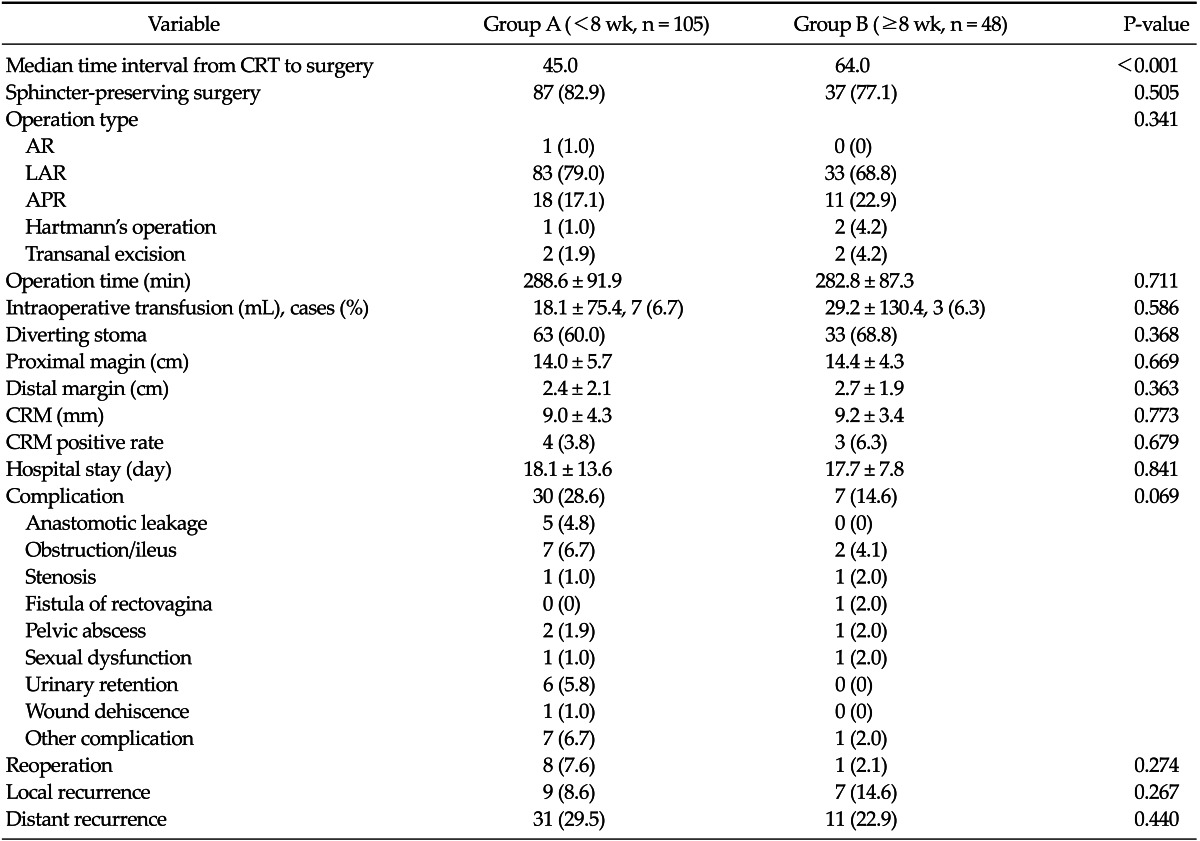

Surgical characteristics and perioperative complications

In group A, patients underwent surgery a mean of 45 days (interval range, 38.8 to 51.2 days) after CRT compared to 66 days (interval range, 55.9 to 76.8 days) in group B. Sphincter preservation was unaffected by the time interval between completion of chemoradiation and surgery (group A, 87 [82.9%] vs. group B, 37 [77.1%]; P = 0.505). The type of surgery (low anterior resection, 75.8%), operative time (median, 286 minutes), resection margin, number of blood transfusions given during surgery (10 cases, 6.5%), length of hospital stay (median, 18 days), and the use of diverting stoma in patients undergoing sphincter-preserving procedures were not influenced by the time interval (Table 2).

Table 2.

Surgical results and complications

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

CRT, chemoradiotherapy; AR, anterior resection; LAR, low anterior resection; APR, abdominoperineal resection; CRM, circumferential resection margin.

A longer interval between chemoradiation and surgery had the effect of decreasing postoperative complications, although statistical significance was not reached (group A, 28.6% vs. group B, 14.6%; P = 0.069). In group A, five anastomotic leakages occurred in contrast to none in group B. There was no significant difference in the rate of local or distant recurrence between the groups.

Pathologic response

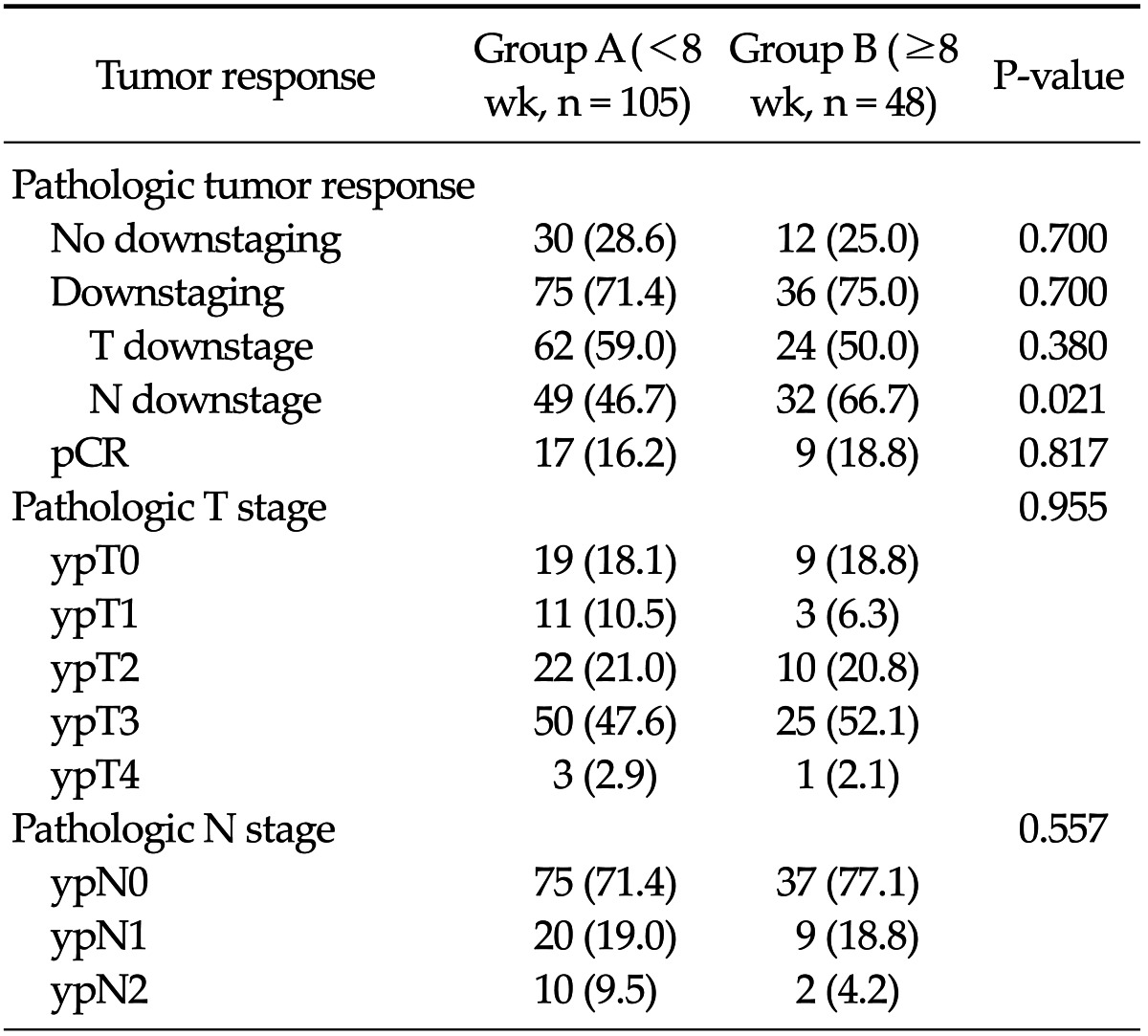

A total of 111 patients (72.5%) experienced overall downstaging (i.e., clinical stage > pathologic stage), and 26 patients (17%) achieved pathologic complete response (pCR). However, 42 patients (27%) did not achieve downstaging (i.e., clinical stage ≤ pathologic stage). No difference in T downstaging was observed (group A, 59.0% vs. group B, 50.0%; P = 0.380). Patients operated after an interval to surgery greater than or equal to 8 weeks (group B) had significantly higher rate of nodal (N) downstaging than those operated less than 8 weeks (group A) after chemoradiation (group A, 46.7% vs. group B, 66.7%; P = 0.021). There was no significant difference in the pCR rate (group A, 16.2% vs. group B, 18.8%; P = 0.817) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathologic response rate after surgery

Values are presented as number (%).

No downstaging, clinical stage ≤ pathologic stage; downstaging, clinical stage > pathologic stage; pathologic complete response (pCR) absence of viable adenocarcinoma cells in the surgical specimen, including primary tumor and lymph nodes (Mandard grade 1).

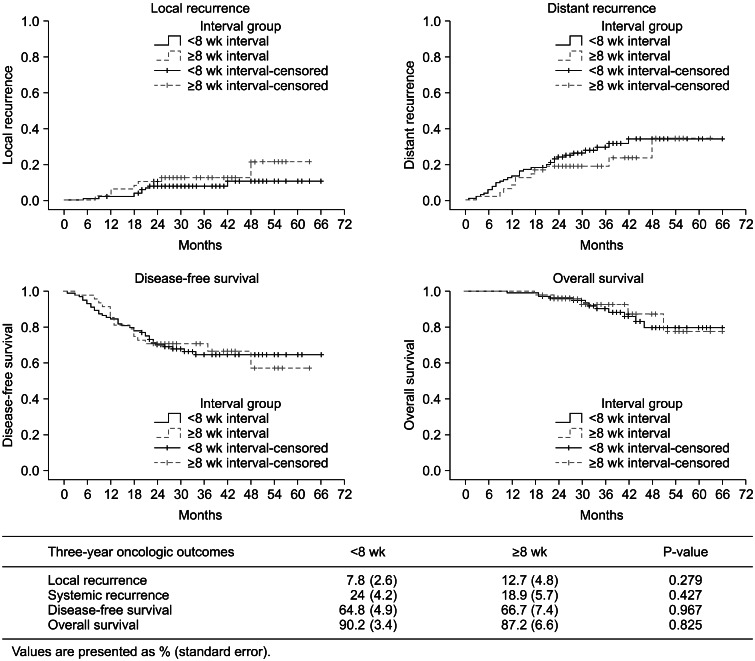

Oncological outcomes

The median follow-up time from surgery was 38 months (range, 19 to 63 months). At 3 years, overall local recurrence was 9.3% (group A, 7.8% vs. group B, 12.7%; P = 0.279), distant metastasis was noted in 26.3% (group A, 24% vs. group B, 18.9%; P = 0.427), DFS was 66.8% (group A, 64.8% vs. group B, 66.7%; P = 0.967), and OS was 91.1% (group A: 90.2% vs. group B: 87.2%, P = 0.825). The local recurrence, distant metastasis, DFS, and OS rates were not significantly different between the groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for oncologic outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by TME is now considered the gold standard for initial treatment of locally advanced rectal cancers [1]. This strategy has been shown to achieve pathologic downstaging and sphincter-preserving surgery as well as improve local control [15,16]. The Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group recently showed that preoperative radiotherapy reduced 10-year local recurrence by more than 50% relative to surgery alone without an OS benefit [7].

After completion of CRT, surgery was usually performed after 4 to 6 weeks, but there were various debates about this period [1,12]. Recently, some investigators suggested that an increased interval was associated with higher rates of pCR and downstaging, decreased recurrence, and improved DFS [4,12,15,17]. Nevertheless, many surgeons were concerned that further delays would increase difficulty with the operation, including fibrosis and may result in increased surgical morbidity [1,4,12,18,19]. For these reasons, some surgeons suggest operation as early as possible, if there is no oncological benefit derived by the difference in time interval between completion of CRT and surgery [2,20-22]. Moore et al. [23] observed more frequent anastomotic complications (0% vs. 7%, P = 0.05) among patients undergoing surgery more than 44 days after chemoradiation. Withers and Haustermans [24] reported that a longer interval after RT may increase the risk of emergence of subclinical tumors, which can grow more rapidly than the primary tumor, and change the risk of developing distant metastases.

However, our findings refute this argument. Although statistical significance was not reached, our findings showed a trend towards decreased postoperative complication rate in patients operated on ≥8 weeks after CRT (group A, 28.6% vs. group B, 14.6%, P = 0.069). No anastomotic leaks occurred in the delayed surgery group (group B). These complication rates compare favorably with previous studies [12,25]. Stein et al. [16] were reported that three patients in the 4- to 8-week interval group had anastomotic leaks and two underwent reoperation, but none of the patients in the 10- to 14-week interval group had leaks. Kerr et al. [25] reported that shorter intervals independently predicted anastomotic leakage and perineal wound complications. Various investigators have confirmed that longer intervals between neoadjuvant CRT and surgery are associated with favorable pathological findings and lower recurrence rates [1,11,13,15,16,23,25].

De Campos-Lobato et al. [1] showed that a more than 8-week interval between completion of CRT and surgery was associated with significant improvement in the pCR rate (30.8% vs. 16.5%, P = 0.03) and decreased the 3-year local recurrence rate (1.2% vs. 10.5%, P = 0.04).

Tulchinsky et al. [15] found that a neoadjuvant CRT-surgery interval >7 weeks was associated with higher rates of pCR and near pCR (17% vs. 35%, P = 0.03), decreased recurrence, and improved DFS (P = 0.05). However, this was not replicated in the present study. We observed a pCR rate of 17%, and there was no difference in the pCR rate between the groups (16.2% vs. 18.8%, P = 0.817). In addition, there were no differences in T downstaging (59.0% vs. 50.0%, P = 0.380). However, our results showed a significantly increased rate of nodal downstaging in patients operated on after an interval ≥8 weeks compared to those operated on after an interval <8 weeks (46.7% vs. 66.7%, P = 0.021).

In many investigations, lower pathological nodal stage was associated with improved recurrence and DFS rates, and is considered a consistent and strong predictor of survival rates [17,26-29]. Kim et al. [29] observed that histopathological N downstaging was the most important prognostic factor. Our study failed to show any significant improvement in oncological outcomes including local recurrence, systemic recurrence, DFS, and OS when surgery was delayed beyond 8 weeks; but we ascertained that there was no higher recurrence rate or lower survival rate associated with delaying surgery. We are confident that such a delay in surgery is not detrimental to patients.

Some investigators attempted to show that an interval longer than 10 weeks between completion of CRT and surgery is more effective. Tran et al. [12] observed that patients had more tumor shrinkage when surgery was deferred for a few more weeks and suggested the adaptation of a delayed interval between chemoradiation and surgery of 10 to 14 weeks. Garcia-Aguilar et al. [13] indicated that increasing the time interval between completion of CRT and TME (to an average of 11 weeks) may increase the pCR rate without significantly increasing CRT- or chemotherapy-related adverse events, operative difficulty, or postoperative complications compared to traditional neoadjuvant CRT and an average delay of 6 weeks.

This study is subject to potential bias and certain limitations due to its retrospective nature. When analyzed this cohort stratified into >10 weeks and >12 weeks, we could not find any statistical significances due to the type and amount of data available. Although our general approach has been to wait 6 to 8 weeks after completion of CRT, the time interval was decided according to individual surgeon preference.

In conclusion, our findings suggested that an interval between neoadjuvant CRT and surgery greater than or equal to 8 weeks showed a trend toward decreased postoperative complication rate and was associated with significantly increasing rate of nodal downstaging. For these reasons, prospective randomized studies of appropriate statistical power comparing various time intervals are required to examine the optimal timing.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.de Campos-Lobato LF, Geisler DP, da Luz Moreira A, Stocchi L, Dietz D, Kalady MF. Neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: the impact of longer interval between chemoradiation and surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SB, Choi HS, Jeong SY, Kim DY, Jung KH, Hong YS, et al. Optimal surgery time after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancers. Ann Surg. 2008;248:243–251. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817fc2a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pahlman L. Optimal timing of surgery after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6:128–129. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Proscurshim I, Nunes Dos Santos RM, Kiss D, Gama-Rodrigues J, et al. Interval between surgery and neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for distal rectal cancer: does delayed surgery have an impact on outcome? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group. Adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic overview of 8,507 patients from 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;358:1291–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:980–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EM, Putter H, Wiggers T, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:575–582. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sebag-Montefiore D, Stephens RJ, Steele R, Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG C016): a multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:811–820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60484-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rodel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folkesson J, Birgisson H, Pahlman L, Cedermark B, Glimelius B, Gunnarsson U. Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial: long lasting benefits from radiotherapy on survival and local recurrence rate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5644–5650. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francois Y, Nemoz CJ, Baulieux J, Vignal J, Grandjean JP, Partensky C, et al. Influence of the interval between preoperative radiation therapy and surgery on downstaging and on the rate of sphincter-sparing surgery for rectal cancer: the Lyon R90-01 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran CL, Udani S, Holt A, Arnell T, Kumar R, Stamos MJ. Evaluation of safety of increased time interval between chemoradiation and resection for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2006;192:873–877. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Aguilar J, Smith DD, Avila K, Bergsland EK, Chu P, Krieg RM, et al. Optimal timing of surgery after chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer: preliminary results of a multicenter, nonrandomized phase II prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2011;254:97–102. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182196e1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heald RJ. A new approach to rectal cancer. Br J Hosp Med. 1979;22:277–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tulchinsky H, Shmueli E, Figer A, Klausner JM, Rabau M. An interval >7 weeks between neoadjuvant therapy and surgery improves pathologic complete response and disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2661–2667. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9892-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein DE, Mahmoud NN, Anne PR, Rose DG, Isenberg GA, Goldstein SD, et al. Longer time interval between completion of neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgical resection does not improve downstaging of rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:448–453. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das P, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Hoff PM, et al. Clinical and pathologic predictors of locoregional recurrence, distant metastasis, and overall survival in patients treated with chemoradiation and mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:219–224. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000214930.78200.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marijnen CA, Kapiteijn E, van de Velde CJ, Martijn H, Steup WH, Wiggers T, et al. Acute side effects and complications after short-term preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision in primary rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:817–825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong RK, Tandan V, De Silva S, Figueredo A. Pre-operative radiotherapy and curative surgery for the management of localized rectal carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD002102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002102.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veenhof AA, Kropman RH, Engel AF, Craanen ME, Meijer S, Meijer OW, et al. Preoperative radiation therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: a comparison between two different time intervals to surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:507–513. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marijnen CA, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, van den Brink M, Maas CP, Martijn H, et al. Impact of short-term preoperative radiotherapy on health-related quality of life and sexual functioning in primary rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1847–1858. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartley A, Giridharan S, Gray L, Billingham L, Ismail T, Geh JI. Retrospective study of acute toxicity following short-course preoperative radiotherapy. Br J Surg. 2002;89:889–895. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore HG, Gittleman AE, Minsky BD, Wong D, Paty PB, Weiser M, et al. Rate of pathologic complete response with increased interval between preoperative combined modality therapy and rectal cancer resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Withers HR, Haustermans K. Where next with preoperative radiation therapy for rectal cancer? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr SF, Norton S, Glynne-Jones R. Delaying surgery after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer may reduce postoperative morbidity without compromising prognosis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1534–1540. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guillem JG, Chessin DB, Cohen AM, Shia J, Mazumdar M, Enker W, et al. Long-term oncologic outcome following preoperative combined modality therapy and total mesorectal excision of locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;241:829–836. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161980.46459.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onaitis MW, Noone RB, Hartwig M, Hurwitz H, Morse M, Jowell P, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer: analysis of clinical outcomes from a 13-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2001;233:778–785. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shivnani AT, Small W, Jr, Stryker SJ, Kiel KD, Lim S, Halverson AL, et al. Pre-operative chemoradiation for rectal cancer: results of multimodality management and analysis of prognostic factors. Am J Surg. 2007;193:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim NK, Baik SH, Seong JS, Kim H, Roh JK, Lee KY, et al. Oncologic outcomes after neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by curative resection with tumor-specific mesorectal excision for fixed locally advanced rectal cancer: Impact of postirradiated pathologic downstaging on local recurrence and survival. Ann Surg. 2006;244:1024–1030. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225360.99257.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]