INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death among women in Canada, with an estimated 1750 deaths and 2600 new cases occurring in 20121. Identifying opportunities for preventing ovarian cancer is particularly important given the high case fatality ratio in this disease and the absence of effective screening. Often, by the time ovarian cancer is detected, it is at an advanced stage of iii or iv.

Recent research has shown that some ovarian cancers (the high-grade serous type) may originate in the fallopian tube mucosa rather than the ovaries2,3. These ovarian cancers represent the most common subtype and have the highest mortality3,4. Other subtypes originating in the ovary may also use the fallopian tube as a conduit for development3. An emerging hypothesis suggests that removal of the fallopian tubes may represent an opportunity to prevent certain types of ovarian cancer from developing, particularly in women already undergoing a hysterectomy for benign indications2–6.

The present analysis examines the use of salpingectomy (surgical removal of the fallopian tubes) with hysterectomy in Canada. Identifying recent use of salpingectomy with hysterectomy across various jurisdictions will help to assess the impact over time of pursuing this emerging hypothesis and whether practice patterns are changing.

METHODOLOGY

The study population included Canadian women 15 years of age and older who were hospitalized during 2006–2011 for a hysterectomy performed in an acute care hospital or day surgery settinga. The objective was to capture hospitalizations that might involve a bilateral salpingectomy performed for prophylactic purposes. Because removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes during a hysterectomy is part of the recommended surgical treatment for certain gynecological cancers, hospitalizations with a recorded diagnosis of ovarian, uterine, cervical, or fallopian tube (and surrounding structures) cancer were excluded. Only hospitalizations with a hysterectomy and a bilateral salpingectomy were included, provided there was no accompanying removal of one or both ovariesb.

RESULTS

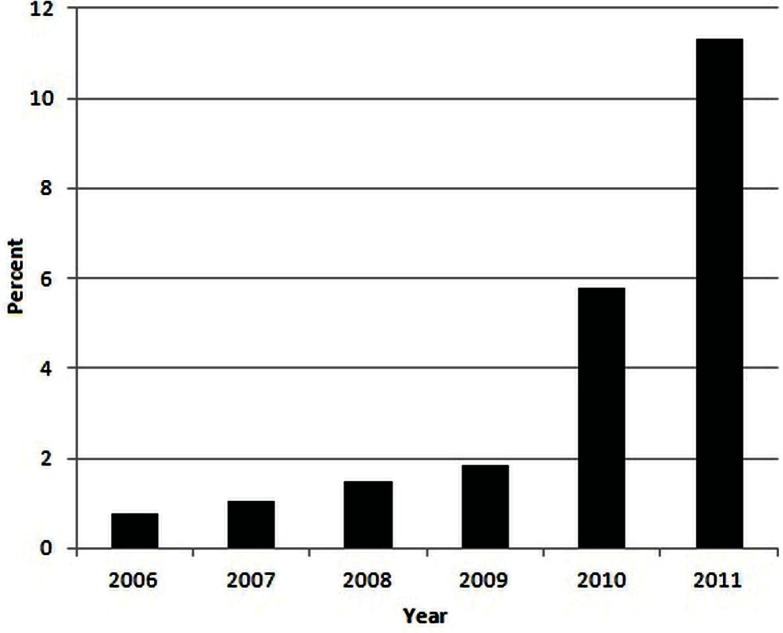

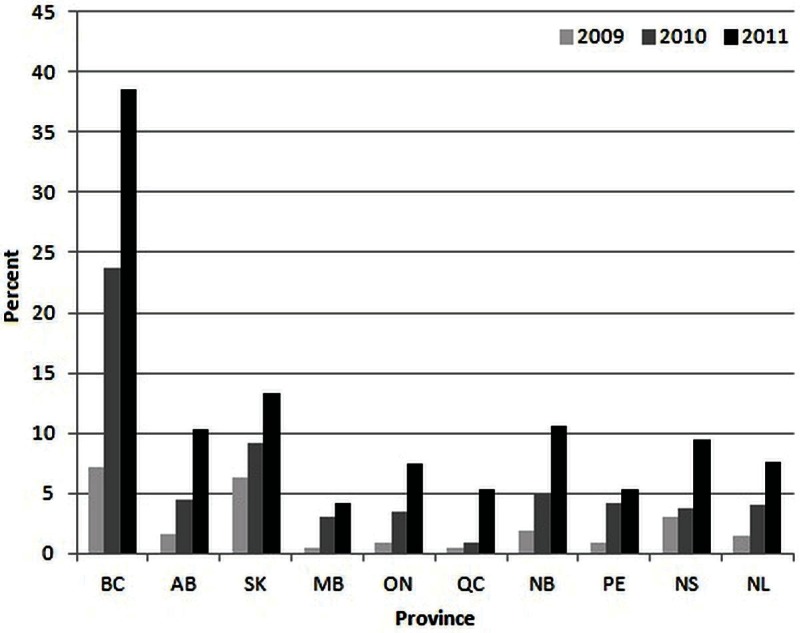

In Canada, the percentage of hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy performed during the same hospitalization has increased in recent years to more than 11% in 2011 from less than 1% in 2006 (Figure 1), with that 11% representing a near-doubling of the rate from the preceding year. In 2011, the percentage of salpingectomies performed varied widely across the province, with all provinces showing an increase since 2009 (Figure 2). In 2011, the percentages ranged from 4.1% in Manitoba to 38.5% in British Columbia.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy, Canada, 2006–2011. Excludes hospitalizations with a recorded diagnosis of ovarian, uterine, cervical, or fallopian tube (and surrounding structures) cancer.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy, by province, 2009–2011. Excludes hospitalizations with a recorded diagnosis of ovarian, uterine, cervical, or fallopian tube (and surrounding structures) cancer.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis shows an increase in the percentage of hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy performed during the same hospitalization (and with no accompanying removal of the ovaries), which suggests a potential change in practice patterns after the publication of recent research that supports a potential ovarian cancer risk reduction with “prophylactic” salpingectomy.

Recent Canadian initiatives arising in British Columbia likely explain the increases recently seen. In 2010, the Ovarian Cancer Research Program (ovcare) in British Columbia directed an educational campaign to all gynecologists in the province about the recent research supporting the hypothesis that ovarian cancers may arise in the fallopian tube. That campaign encouraged consideration of opportunistic salpingectomy as an ovarian cancer risk–reduction strategy in all women undergoing hysterectomy for benign indications3. All gynecologists in Canada were also sent a survey about baseline knowledge and interest in a national strategy for preventing ovarian or fallopian tube cancers with salpingectomy. In 2011, the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists of Canada formally acknowledged the “prevention potential” of salpingectomy in a statement recommending that physicians discuss its risks and benefits with patients undergoing a hysterectomy4. The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists of Canada also highlighted the need for a national study focused on the effectiveness and safety of prophylactic salpingectomy completed under those circumstances.

It is recommended that female BRCA mutation carriers, all of whom are at elevated risk for developing ovarian cancer, undergo prophylactic removal of both their ovaries and their fallopian tubes (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) well before menopause7. Although many carriers choose this option, a significant proportion do not. Increases in cardiovascular, psychosexual, and cognitive dysfunction are reported in women experiencing premature menopause because of such a procedure5. Recently, removal of the fallopian tubes with preservation of the ovaries has been proposed as an intermediate step for high-risk women who have completed child-bearing but who are not prepared to undergo premature menopause because of oophorectomy. A recent modelling study showed that though bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is projected to achieve greater ovarian cancer risk reduct ion for BRCA mutation car r iers, bilateral salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy is a cost-effective alternative8. However, by performing salpingectomy alone, with conservation of the ovaries, a residual risk of developing ovarian cancer remains. Subsequent surgery to remove the ovaries brings with it renewed potential for surgical complications, and the opportunity for breast cancer risk reduction associated with premature menopause may be lost6.

Further investigation into the use of salpingectomy as a prophylactic procedure for ovarian cancer is required. The present analysis provides a first look at the extent that salpingectomy with hysterectomy is being used in Canada, and if forms the background for future research studies. Other analyses, including looking at differences by income, urban or rural status, and hospital type, and examining complications in women undergoing the procedure, are underway. Continued monitoring of rates of salpingectomy with hysterectomy, together with ovarian cancer incidence and mortality over time, can also help to assess the effect of this intervention and whether its propagation is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data were provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Information. The methodology notes were reviewed by Yana Gurevich and Opeyemi Fadahunsi. Public-use slides of figures in this communication can be downloaded at http://www.cancerview.ca/downloadableslides.

Footnotes

Health administrative data from fiscal years 2006–2007 and 2010–2011 were used. Data sources: Discharge Abstract Database, National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, Canadian Institutes for Health Information; Fichier des hospitalisations med-écho, Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec; Alberta Ambulatory Care Reporting System, Alberta Health and Wellness.

It is not known whether the selected women undergoing hysterectomy had any ovaries before the surgery.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee on Cancer Statistics . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2012. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvador S, Gilks B, Köbel M, Huntsman D, Rosen B, Miller D. The fallopian tube: primary site of most pelvic high-grade serous carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:58–64. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e318199009c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tone AA, Salvador S, Finlayson SJ, et al. The role of the fallopian tube in ovarian cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10:296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists of Canada (goc) GOC Statement Regarding Salpingectomy and Ovarian Cancer Prevention. Ottawa, ON: GOC; 2011. [Available online at: http://www.g-o-c.org/uploads/11sept15_gocevidentiarystatement_final_en.pdf; cited February 11, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietl J, Wischhusen J, Häusler SF. The post-reproductive Fallopian tube: better removed? Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2918–24. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene MH, Mai PL, Schwartz PE. Does bilateral salpingectomy with ovarian retention warrant consideration as a temporary bridge to risk-reducing bilateral oophorectomy in BRCA1/2mutation carriers? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:19.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebbeck TR, Kauff ND, Domchek SM. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingooophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:80–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon JS, Tinker A, Pansegrau G, et al. Prophylactic salpingectomy and delayed oophorectomy as an alternative for BRCA mutation carriers. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:14–24. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e3182783c2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]