Abstract

Extrusion-cooked instant rice was prepared by optimizing the formulation with emulsifiers, glycerol monostearate (GMS), soybean lecithin (LC), and sodiumstearoyl lactylate (SSL), and thickeners, gum Arabic (GA), sodium alginate (SA), and sticky rice (SR). The emulsifiers addition caused increase of degree of gelatinization (DG), and decrease of water soluble carbohydrate (WSC), α-amylase sensitivity, water soluble index (WAI) and adhesive for extrudates, while the thickeners addition increased extrudates DG, bulk density (BD), WSC, α-amylase sensitivity, WAI, hydration rate (HR) and adhesiveness. Based on the data generated by a single additive at various levels, optimum formulation was obtained employing orthogonal matrix system with combination of the selected additives for extrusion cooking. Extrudates were evaluated for optimum hydration time followed by drying to prepare the finished product. Texture profile analysis and sensory evaluation indicate that quality of the finished product is equivalent to that of the round shaped rice and superior to a commercial instant rice product. This study also demonstrates possibility of value-added and versatile instant rice product development using broken rice.

Keywords: Extrusion cooking, Instant rice, Emulsifier, Thickener, Broken rice, Orthogonal matrix

Introduction

Rice is widely consumed as a staple food in Asia (Juliano 1996). Some unique functional properties of rice such as flavor carrying capability, hypoallergenicity, and bland flavor make it a desirable grain to be used in value-added products. Some examples of these products include gluten-free rice bread (Deis 1997), tortilla, beverages, processed meats, and low-fat sauces, puddings, or salad dressings (McCue 1997). Modifying the rice flour can change its functional properties in such a way that it may also be used as a substitute in other value-added products.

The accelerated pace of modern life has promoted new applications of staple rice to the preparation of instant (quick-cook) rice, which is fully or partially cooked and dehydrated, and it takes only 3–5 min to prepare for consumption after rehydration. Various forms of instant rice products, such as expanded, frozen, and dried were produced to meet consumer’s demand (Kang et al. 2007). While convenient, eating quality of instant rice is not as good as that of regular rice because of organoleptic and nutritional loss during preparation (Champagne and Lyon 1998; Juliano and Hicks 1996; Semwal et al. 1996).

With the advantages of versatility, high productivity, low cost, energy efficiency, and no effluents causing waste problems, extrusion cooking is an attractive process to modify the functional and digestible characteristic of cereal grains. Although it has been extensively used to produce such products as cereals, snacks, bread substitutes, precooked flours, animal feeds, and dietetic foods (Camire et al. 1990), only in recent years as it has been used for rice products (Pan et al. 1992; Panlasigui et al. 1991, 1992; Bryant et al. 2001; Hagenimana and Ding 2005). Process involving high pressure/temperature and shear during extrusion cause starch gelatinization, protein denaturation, enzyme inactivation, and Maillard reactions, and thus nutritional loss (Cheftel 1986; Eggum et al. 1986). Additives have been widely used to improve extrudate quality (Kaur et al. 2000). Addition of lipid (oleic acid, dimodan, soya lecithin and copra) caused less degradation of macromolecules (Colonna and Mercier 1983). Rice-green gram blend showed marked changes of lightness (L*) and yellowness (b*) of the extrudate (Bhattacharya et al. 1997). Glyceryl monostearate, glyceride and soybean lecithin were added into extruded rice to improve texture, to reduce adhesiveness, and to retain extrudate final shape after hydration (Smith et al. 1985). Xanthan gum, β-cyclodextrin, guar gum and carrageenan were added as a binder for extruded rice product and shown advantages for rehydration and shape maintenance (Wang et al. 2001). Sodium hydroxide, phosphate, and citric acid were added to improve degree of gelatinization, water absorption index and rehydration ratio (Bhaskar et al. 1989). From previous reports, it is clear that there are three essential indexes difficult to control in the preparation of extrusion-cooked instant rice product: 1) rehydration time, 2) shape, and 3) textural properties. All these three indexes have been affected by extrusion parameters and components. Excellent studies have been reported for optimum extrusion parameters (El-Dash et al. 1983; Shankar and Bandyopadhyay 2005; Chakraborty and Banerjee 2009). However, few studies have reported on the use of emulsifier in combination with thickener in an effort to improve product quality of extruded instant rice.

Therefore, the objective of this research was to investigate the effects of added emulsifier, thickener, or combination of them on physical, chemical, and textural properties of instant rice extruded by a single screw extruder using broken rice.

Materials and methods

Broken rice and sticky rice (SR) were obtained from Xinghua Rice Industry Co., Ltd. in Jiangsu Province, China. Emulsifiers, glycerol monostearate (GMS), soy lecithin (LC), and sodium stearoyl lactate (SSL) and thickeners, gum Arabic (GA) and sodium alginate (SA) were purchased from Shanghai United Food Additives Co., Ltd. α-amylase (100 000 U/ml) from Bacillus Licheniformis was obtained from Sigma Aldrich Trading Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), soluble starch was from Sinopharm (Beijing, China).

Preparation of rice flour (RF)

Broken rice was ground by hammer mill (model No., manufacturer, city, country) and sifted through 60-mesh screen. Appropriate amount of water was added to adjust the rice flour to three different moisture levels (28%, 32%, and 36%, W/W). Prepared rice flour cum dough type material was sealed in polyethylene bags and equilibrated for 24 h at 4 °C to avoid microbial growth before extrusion.

Extrusion of RF

Extrusion was performed in a single-screw extruder (PSPH 55, Cereal Machinery, Wuxi, Jiangsu, China), consisting of three independent zones of controlled temperature in the barrel (feeding, compression, and metering). Diameter of the screw was 80 mm. The length to diameter ratio of the extruder barrel was 10.5:1. Diameter of the hole in the die was 1.5 mm with a die length of 4.2 mm. The extruder was fed with the prepared RF manually through a conical hopper, keeping the flights of the screw fully filled and avoiding accumulation of the feeding material in the hopper. After stable conditions were established, extrudates were collected and cool dried under mild air flow conditions at room temperature overnight and then finish dried to moisture content of 9–10% (wet basis) by an air convection oven at 45 °C and wind flow at 0.1 m/s.

To optimum the extrusion conditions, three screw speeds (150, 250, and 300 rpm) and three temperatures (30°, 50°, and 70 °C) of the third barrel section (metering section) were selected following An’s report (An et al. 2006), the other temperatures were maintained at 25 °C. Therefore, a total of 27 extrusions (three moisture levels, screw speeds, and barrel temperatures, respectively) were conducted, and three replications of each extrusion run were performed. Dried samples were stored in air tight plastic containers at room temperature until used for analysis.

Pasting properties

Extruded RF was studied for pasting properties using Brabender Micro Visco-amylograph (Model No., City, Germany). Extrudate was ground using a hammer mill (6F-1830 rice miller. Tiantai miller Co.Ltd., Henan, China), sifted through 60 mesh screen (diameter of 20 cm), and the sample powder was dispersed in water (8%, W/W). Prepared slurry (100 ml) was then placed in the Visco-amylograph. The amylograph was set to equilibrate the slurry at 30 °C for 2 min, heated to 92 °C with the heating speed of 7.5 °C per min, held at 92 °C for 5 min, and cooled to 30 °C at the cooling speed of 7.5 °C per min. Pasting behavior was recorded through resistance of the paste against a rotating spindle during sample heating and cooling periods. The detecting range was 700 cmg with rotating spindle speed at 250 rpm, and pasting property was expressed by Brabender Unit (BU).

Preparation of reformed rice (RR)

A single additive, either an emulsifier or a thickener, was blended with RF using a Hobart mixer (Hobart Food Equipment Group, Troy, OH, USA). Moisture content of the mix was adjusted to 32%. Prepared mixture was extruded at a metering zone barrel temperature, 70 °C and a screw speed, 250 rpm. Table 1 shows formulation with a single ingredient added at different levels. A portion of RR was subjected to physical and chemical analyses. Rest of the RR was shaped into cooked rice by cutting the extrudates using a mould prepared at a local machine shop as described by Jin (Jin et al. 2010), and used for texture profile analysis.

Table 1.

Various properties of reform extruded rice on addition of emulsifiers and thickeners

| Sample | Added ingredient (%) | DG (%) | BD (g/ml) | WSC (%) | WSP (%) | α-Amylase Sensibility (g reducing sugar/g) | WAI (g/g) | HR (%) | Hardness (g) | Adhesive (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broken rice | 32 | 63.6 | 0.71 | 11.98 | 2.52 | 380.4 | 4.61 | 250 | 159.05 | −0.93 |

| Added ingredient | ||||||||||

| GMS | 0.25 | 74.8 | 0.72 | 11.52 | 2.46 | 336.6 | 4.36 | 249 | 159.16 | −0.91 |

| 0.5 | 73.8 | 0.75 | 9.6 | 2.06 | 238.4 | 4.15 | 243 | 161.18 | −0.85 | |

| 1.0 | 73.2 | 0.78 | 6.14 | 1.91 | 187.1 | 3.59 | 221 | 169.94 | −0.78 | |

| 1.5 | 72.1 | 0.80 | 4.5 | 1.83 | 157.3 | 3.57 | 206 | 172.55 | −0.71 | |

| 2.0 | 69.2 | 0.82 | 3.5 | 1.69 | 156.5 | 3.51 | 203 | 175.33 | −0.59 | |

| SSL | 0.25 | 75.9 | 0.70 | 10.02 | 2.55 | 337.1 | 4.59 | 258 | 156.32 | −0.90 |

| 0.5 | 74.6 | 0.68 | 9.23 | 2.61 | 331.5 | 4.51 | 260 | 152.52 | −0.85 | |

| 1.0 | 72.5 | 0.63 | 9.13 | 2.63 | 294.2 | 4.47 | 265 | 144.87 | −0.81 | |

| 1.5 | 71.4 | 0.59 | 9.0 | 2.69 | 287.2 | 4.41 | 271 | 132.66 | −0.76 | |

| 2.0 | 70.8 | 0.51 | 8.9 | 2.73 | 274.1 | 4.33 | 275 | 131.22 | −0.71 | |

| LC | 0.25 | 76.1 | 0.71 | 11.28 | 2.56 | 331.3 | 4.51 | 253 | 153.66 | −0.92 |

| 0.5 | 74.8 | 0.70 | 10.02 | 2.63 | 288.5 | 4.32 | 261 | 150.48 | −0.86 | |

| 1.0 | 73.4 | 0.68 | 9.52 | 2.67 | 285.7 | 4.25 | 272 | 145.66 | −0.80 | |

| 1.5 | 72.7 | 0.67 | 9.02 | 2.72 | 280.5 | 4.11 | 279 | 139.68 | −0.76 | |

| 2.0 | 71.5 | 0.63 | 6.65 | 2.77 | 277.1 | 4.08 | 281 | 138.16 | −0.69 | |

| SA | 0.2 | 72.5 | 0.72 | 12.05 | 2.55 | 388.3 | 4.81 | 261 | 144.62 | −1.05 |

| 0.5 | 73.1 | 0.73 | 13.71 | 2.61 | 390.1 | 4.85 | 277 | 135.29 | −1.12 | |

| 0.8 | 73.5 | 0.75 | 14.77 | 2.64 | 394.4 | 4.87 | 283 | 129.79 | −1.28 | |

| 1.1 | 74.2 | 0.78 | 15.3 | 2.68 | 402.3 | 5.07 | 295 | 127.35 | −1.37 | |

| GA | 0.2 | 70.6 | 0.73 | 12.23 | 2.50 | 381.1 | 4.65 | 253 | 139.12 | −1.01 |

| 0.5 | 71.3 | 0.75 | 13.09 | 2.44 | 388.3 | 4.72 | 255 | 135.4 | −1.08 | |

| 0.8 | 72.1 | 0.78 | 13.12 | 2.38 | 394.8 | 4.81 | 269 | 131.07 | −1.15 | |

| 1.1 | 73.2 | 0.80 | 13.27 | 2.29 | 403.1 | 4.96 | 283 | 123.39 | −1.25 | |

| SR | 5 | 72.1 | 0.79 | 12.2 | 2.55 | 383.4 | 4.73 | 253 | 149.28 | −0.94 |

| 10 | 73.3 | 0.93 | 14.2 | 2.68 | 390.2 | 4.92 | 268 | 142.53 | −1.03 | |

| 15 | 73.5 | 0.73 | 15.8 | 2.77 | 405.3 | 5.16 | 272 | 139.59 | −1.09 | |

| 20 | 74.3 | 0.72 | 16.1 | 2.86 | 416.5 | 5.35 | 284 | 133.72 | −1.19 | |

Each observation is a mean of three replicate experiments. Moisture content of feeding material, extrusion temperature and screwing speed was 32%, 60 °C and 250 rpm, respectively

GMS glycerol monostearate, SSL sodium stearoyl lactate, LC soy lecithin, SA sodium alginate, GA gum Arabic, SR sticky rice

Determination of physical and chemical properties

Physical and chemical analyses, except for the determination of hydration rate were ground in a mill (6F-1830 rice miller. Tiantai miller Co.Ltd., Henan, China) and sifted through 60-mesh screen. The powder was sealed in polyethylene bags and stored at room temperature until used for analysis.

α-Amylase susceptibility (AS)

α-Amylase Susceptibility (AS) was measured following the modified procedure described in previous report (Zavareze et al. 2010). Ten grams of sample flour was dispersed in 47 ml phosphate buffer (0.2M, pH 6.0). One millilitres of α-amylase solution (537.5 U/ml) was added to the slurry and the mixture was incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 20 min. Then, 1 ml of 0.1 N HCl was added to inactive the enzyme, and neutralized with 1 ml of 0.1 N NaOH, followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The reducing sugars present in the supernatant were determined by Nelson-Somogyi method (Somogyi 1945). One unit of α-amylase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme which liberated reducing sugar equivalent to 1 μg of D-glucose per minute from soluble starch at 25 °C.

Bulk density (BD)

BD was determined using a modification of a reported method (Bryant et al. 2001). Each sample (10 g) was weighed into a 25-ml graduated cylinder. The cylinder was tapped on the bench top until no more settling was observed. A reading was taken both before and after packing. BD was expressed as grams per cubic centimeter.

Degree of gelatinization (DG)

DG was determined following the procedures in the report by Chiang et al. (Chiang and Johnson 1977). A sample of flour (20 mg) was dispersed in 5 ml distilled water to prepare partially gelatinized starch in the sample slurry. Another 20 mg of sample flour was added into a solution containing 3 ml of distilled water and 1 ml of 1N NaOH to prepare totally gelatinized starch in the sample slurry. 1 ml of 1 N HCl was added to this solution 5 min later. Both prepared sample solutions were reacted with 25 ml glucoamylase solution and digested at 40 °C for 30 min. Glucoamylase solution was prepared by 1) dispersing 2 g of Rhizopus glucoamylase (Sigma Chemical Co.) in 250 ml of acetate buffer, and 2) rapidly filtering through glass filter paper (Whatman No. GF/A). Prepared solution was used within 2 h. Specific activity of the glucose amylase was 28.4 μmol glucose formed/min/mg protein at pH 4.5 and 40 °C. Glucoamylase was inactivated by adding 2 ml 25% trichloroacetic acid solution. The reaction dispersion was 1) centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, 2) 0.5 ml of the supernatant was reacted with 4.5 ml of ο-toluidine and boiled for 10 min, 3) 5 ml of glacial acetic acid was added after cooling, and 4) the color was measured with a spectrophotometer at 630 nm. Glucose was used for the preparation of standard curve. DG was calculated by the ratio of glucose released from partially gelatinized starch to that released from totally gelatinized starch in the samples, following the equation shown in the report (Chiang and Johnson 1977).

Hydration ratio (HR)

HR was measured following the procedures described in the report (Yu et al. 2009). The extrudate was cut into 35-mm long strands, and around 20 g strands were weighed (M1) and placed in 500 ml of water at 30 °C for 15 min. The water was drained, and the hydrated samples were weighed (M2). HR was defined as:

|

Water absorption index (WAI)

WAI was determined based on the procedures of previous report (Anderson et al. 1969). 2.5 g of sample powder was suspended in 30 ml of distilled water in a 50-ml tared centrifuge tube, and stirred at 30 °C for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 3000× g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and gel was weighed. WAI was the ratio of gel weight to sample weight.

Water soluble carbohydrate (WSC)

Sample preparation was carried out according to report (Margalli and Lopenz 2006). 100 mg of sample powder was dispersed into 10 ml hot water by stirring at 80 °C for 10 min. Suspensions were filtered and diluted to 100 ml. WSC were determined by the phenol/sulfuric acid method (Dubois et al. 1956) using glucose as a standard. 2 ml of sample solution was pipetted into a colorimetric tube, and 0.05 ml of 80% phenol was added. Then, 5 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid was added rapidly, the tubes were allowed to stand 10 min, and they were shaken and placed for 15 min in a water bath at 25 °C. The absorbance was determined at 490 nm.

Water soluble protein (WSP)

Sample preparation was followed the procedures in the report by Camire (1991). 200 mg of sample powder was dispersed into 10 ml of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 1% beta-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) in an ampoule. The ampoule was sealed and rocked overnight at room temperature. The next morning the amploule was carefully broken open the ampoule at the neck and the content was diluted with distilled water for four folds. WSP was analyzed according to a modified Lowry protein assay (Hartree 1972) using Bovine Serum Albumin as standard. When detecting, 1 ml of the diluted samples was mixed with 0.9 ml of potassium sodium tartrate (2 mg/ml)-Na2CO3 (100 mg/ml) solution in tubes. The tubes were placed in a water bath at 50 °C for 10 min, cooled to room temperature, and treated with 0.1 ml of potassium sodium tartrate (20 mg/ml)-CuSO4·5H2O (10 mg/ml)-NaOH (0.1 mol/l) solution for 10 min. Then 3 ml of new prepared Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (0.15 mol/l) was pipetted into the tube and heated to 50 °C for 10 min and cooled to room temperature. Absorbencies were read at 650 nm.

Preparation of complex reformed rice (CRR) employing orthogonal matrix system

Based on the data of physical and chemical properties of RR, L9 (34) orthogonal and range analyses were conducted in order to optimize the formulation using emulsifiers and thickeners in the preparation of complex reformed rice (CRR). Table 2 shows factors and levels selected for orthogonal and range analyses. Prepared CRR was cut into rice shape, and soaked in two fold of hot water (80 °C) for 5 min and cooked for 10 min at 100 °C. Extra-water was drained and the cooked CRR was dried in an oven at 70 °C for 2 h. This was designated as instant CRR (ICRR).

Table 2.

Factors and levels selected for orthogonal experiments

| Factor level | A GMS(%) | B SA(%) | C SSL(%) | D SR(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 5 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 10 |

| 3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 15 |

Texture profile analysis

A compression test was performed using XTi2 Texture Measuring Machine (Stable Microsystems, UK) on RR, CRR, and ICRR. A sample of rice-shaped RR, CRR, or ICRR was compressed to 50% deformation. The plunger was withdrawn to the original height, and the sample was rested for 5 s, followed by compression-withdraw cycle at 50% deformation. Speed of compression head was adjusted to 2 min/s. The hardness value is a maximum peak force during the first compression. Adhesive force is a maximum negative peak force after the first compression. Springiness was defined as the degree or rate at which the sample returns to its original size/shape after partial compression between the tongue and palate. The definition of chewiness was the total amount of work necessary to chew a sample to a state ready for swallowing (Meullenet 1998).

Sensory analysis

Eight evaluation personnel were selected for sensory analysis. They were trained for colour, mouth feel, elasticity, viscosity, ripeness of rice evaluation. Maximum score was set as 5, each personnel gave their grade, final total scores were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the means of triplicate determinations. Statistical significance was assessed with one-way analysis of variance using SPSS 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Window program. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Result and discussion

Extrusion parameters and pasting properties

Starch as the main component of rice goes through expansion and degradation during extrusion. Pasting behavior of rice could reflect the integrity of starch granule, and hydration property is essential to gelatinization of starch (Prasert and Suwannaporn 2009). The two indexes, pasting behavior and hydration property were selected to evaluate quality values of extruded rice product in this study.

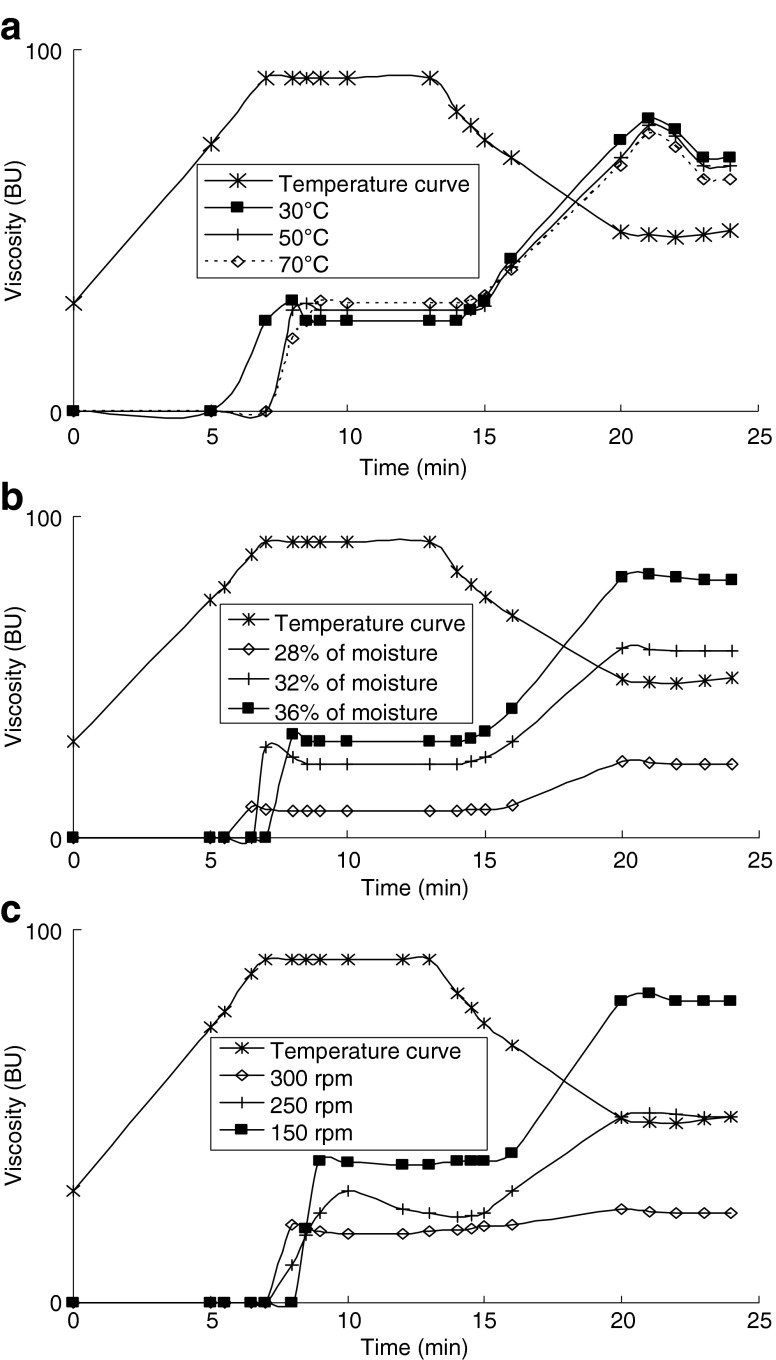

The viscosity of a paste depends on a large extent on the degree of gelatinization of the starch granules and the extent of their molecular breakdown (El-Dash et al. 1983). In fact, the values for peak of viscosity (PV) of extrudates were associated with ungelatinized starch. The pattern in Fig. 1a–c shows a shift in PV to the left (increase in cold viscosity) with barrel temperature, moisture and screw speed decrease. Although PV shift pattern were the same, except a decrease in viscosity of the new peak (increase in degradation) with moisture and speed decrease, which decreased the degree of cooking indicates breakdown of polymers. From Fig. 1b and c, we could observe that the gelatinization temperatures varied with extrusion temperature and screwing speed variation. The cold paste viscosity (CPV) indicates the extent of starch retrogradation that occurs during the cooling process. The CPV decreased with increasing of barrel temperature, as well as increased with increasing of moisture content and screwing speed (Fig. 1a–c). All of the CPV was much higher than Peak Viscosity, indicating rearrangement of starch molecules during cooling.

Fig. 1.

a Amylograms of sample extruded at different temperature, 34% of moisture and 250 rpm of speed. b Amylograms of sample extruded at different moisture, at temperature of 70 °C and speed of 250 rpm. c Amylograms of sample extruded at different screwing speed, at moisture of 32% and temperature of 70 °C

The holding strength of pastes in all Amylogams during heating and subsequent cooling indicates partial pasting of starch occurred in the barrel during extrusion. This observation on pasting behavior is supported by a previous report (Hagenimana and Ding 2005).

There were no significant differences in viscosities among three rice extrudates prepared by different barrel temperatures throughout heating and cooling cycle (Fig. 1a). However, viscosities were higher throughout the heating-cooling cycle as moisture content (Fig. 1b) of the extrudates and screw speed (Fig. 1c) increased.

Moisture in the feed plays a significant role in keeping possession of integrity of starch molecular structure during extrusion. In case of 28% moisture in the feed as can be seen in Fig. 1b, rice starch granules severely damaged and fragmented during extrusion absorbed water faster than those in other two extrudates with 32% and 36% moisture, and started to increase viscosity earlier, showing lower pasting temperature compared to higher moisture feeds. Significantly damaged starch granules, however, showed much lower CPV. In Fig. 1c, high screw speed (300 rpm) bring about shorter residence time of rice in the barrel, resulting in less damage to rice starch granules compared to the screw speed at 250 or 150 rpm during extrusion.

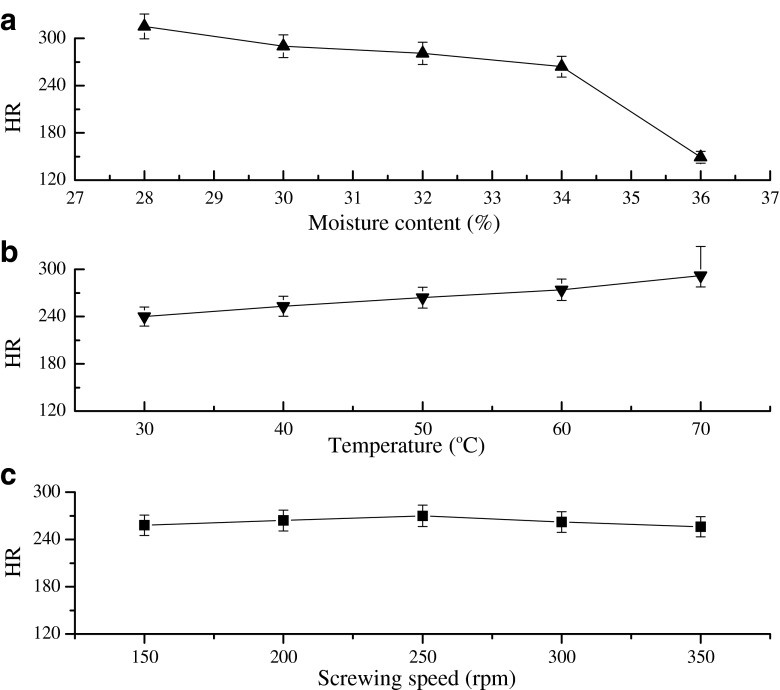

As mentioned earlier, increased amount of moisture in the feed enhanced lubrication action, resulting that less number of starch granules are damaged as well as gelatinized during extrusion cooking. There are more rice starch granules with orderly arranged internal structure than those with disrupted structure after extrusion, causing less absorption of water under the conditions for hydration employed in this study (88 °C for 7 min) as shown in Fig. 2a. A drastic decrease in HR was observed at above 34% moisture content in the feed. As is expected, HR increased with increasing extrusion temperature (Fig. 2b). This indicates increasing barrel temperature for extrusion generated increasing number of starch granules with disrupted rigid starch during extrusion, facilitating hydration of rice starch. A positive relationship between temperature and HR of instant rice has also been reported (Puspitowati and Driscoll 2007). Changes in screw speed did not show significant effect on HR (Fig. 2c). HR seemed to slightly increase as screw speed increased up to 250 rpm, but to decrease without significance as screw speed further increased.

Fig. 2.

a Various moisture content on hydration ratio, at temperature of 60 °C and speed of 250 rpm. b Various temperature on hydration ratio, at 34% of moisture and 250 rpm of speed. c Various screwing speed on hydration ratio, at moisture of 34% and temperature of 60 °C

Results presented in Figs. 1 and 2 show pasting and hydration properties are dependent on the combined effects of moisture, extrusion temperature, and screw speed. In consideration of those properties, 32% for moisture content of feed, 60 °C for barrel temperature, and 250 rpm for screw speed were employed for the preparation of RR, CRR, and ICRR.

Emulsifier and thickener addition on characteristics of RR

Extrudate characteristics depend on physicochemical changes occurring during extrusion. Under stationary extrusion condition determined above, emulsifiers GMS, SSL and LC with different contents (0.25%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, w/w) and thickeners SA and GA (with content of 0.2%, 0.5%, 0.8% and 1.1%), and SR (at content of 5%, 10%, 15% and 20%) were blended with RF, the characteristics of extrudates were investigated as shown in Table 1.

DG, BD, WAI and HR

The process of gelatinization is unique to starches and important in many products and is responsible for their desired characteristics (Puspitowati and Driscoll 2007). From Table 1, we observed that DG decreased with more emulsifier addition, and increased with thickener increasing. Interestingly, DG of RR with both emulsifier and thickener added were much higher than that of control (63.6%). Decrease trends for emulsifier was probably due to the presence of hydrophobic group and hydrophilic group result in complexes formed with rice component during extrusion, which would help avoid of starch degradation. But overmuch emulsifier addition would lubricate the barrel, and decrease friction between barrel and feeds, which results in low thermal energy, so did the high DG. With high adhesive of thickeners, the friction between barrel and feed would strength, so the thermal energy, which result in increase of DG for all thickener added reform rice.

The BD of extrudates is important in relation to their ability to float or sink when poured into water and their packing requirement. As gelatinization increased, the volume of extruded products increases and bulk density decreases (Case et al. 1992; Mercier and Feillet 1975). In the present study, for emulsifier added extrudates, the BD of extruded products increased with increasing GMS (varies from 0.72 to 0.82 g/ml) and decreased with increasing of SSL (from 0.70 to 0.51 g/ml) and LC (from 0.71 to 0.63 g/ml). Different trends were found for thickeners added extrudates. BD of reform rice increased with more SA and GA addition, but for SR added reform rice, BD increase first and reached to the maximum (0.93 g/ml) at 10% content addition, and then decrease.

WAI of the GMS extrudates decreased from 4.36 to 3.51 g/g, which was less than control (4.61 g/g), while for SSL and LC added extrudates, no significant (p > 0.05) decrease of WAI were found (4.33 g/g for 2.0% SSL, 4.08 g/g for 2.0% LC) though slight decrease existed. The reason cause differences between GMS added extrudates and LC, SSL added extrudates probably was that GMS is lipophilic emulsifier with nonpolar group, which might form complexes with amylose hydrophobic helix during extrusion, while SSL and LC were hydrophilic emulsifier with polar charge, which would form cross-linking with protein and starch. The complex of GMS with amylose, would prevent of leaching of amylose during gelatinization, inhibits swelling of starch granules heated in water, and reduces the water binding capacity of starch when added in starch (Eliasson and Krog 1985; Charutigon et al. 2008). And SSL (LC)-starch (protein) cross-linking may lower the swelling capacity and WAI of the starch granules (Rutenberg and Solarek 1984; Wang et al. 1999). Further, lubrication effects would play a role for WAI decrease, because previous report pointed out that the lubrication effect of mono and tri-glycerides does not depend on their complexation (Conde-Petit and Escher 1995). Three thickeners increased the WAI with additive content increasing, but WAI values for GA added extrudate was less (3.94–4.26 g/g) than control. The highest WAI (5.35 g/g) was found for SR extrudates with 20% addition, which was significantly higher than control (p < 0.05). Thickeners containing hydrophilic groups (such as hydroxy, carboxyl and amino) can strength not only the consistency but also the water retaining capacity of food system(Casas and Carcia 1999). The differences in the results of these studies may be attributed to varying degrees of depolymerization or resistant starch formation resulting from extrusion cooking, in addition to the above-mentioned complex formation.

HR of GMS added extrudates decreased with more additive content (249–203%), and significantly difference were found when content reached 1.0% compared with control (250%). However, for SSL and LC added system, increase of HR with increasing content was observed (258–275% for SSL and 253–281% for LC). Thickener SA, GA and SR added extrudates all increased HR with additive increasing. Among which, the addition of SA significantly increased (p < 0.05) the HR when added content be equal or greater than 0.5%. It was speculated that SA has abilities of high water affinity and thermostability (Miura et al. 1999), and resulted in the same properties for extrusion reform rice. In order to improve the HR of reform rice, SR and SA were selected for complex reform rice preparation.

WSC, WSP and α-amylase susceptibility

WSC and α-amylase susceptibility of RR were all decreased with three emulsifier content increasing, the values were significantly lower (p < 0.02) than that of control (11.98%) when added content greater than 0.5%. Different observations reported that tristearin did not change WSC in extruded corn starch at a level of substitution (Collier and O’Dea 1983). In reverse, thickener added system give much higher WSC and α-amylase susceptibility than control, and also increased the WSC values with added content increasing. Similar report showed that amount of WSC of extruded corn starch was previously reported decrease with increasing amylose content. Extrusion cooking is responsible for gelatinization and degradation of starch and also for changing the extent of molecular associations between components, e.g. the amylose-lipid complex. The increased levels of crystalline in the samples extruded with MG and fatty acids were reported due to the crystallization of amylose lipid complexes and the reduction in starch degradation due to the lubricating effect of the additives (Mercier and Feillet 1975). Kirby et al. (1988) confirmed the breakdown of maize structure necessary for high solubility and high expansion, on this basis, fatty acids and MG added to starch be expected to lead to low solubility and low expansion, as observed in previous studies on starches (Faubion and Hoseney 1982; Bhatnagar and Hanna 1994) and cereal flours (Malkki et al. 1984; Schweizer et al. 1986; Galloway et al. 1989; Hu et al. 1993; Ryu et al. 1994). These changes provide a plausible explanation for the differences in starch α-amylase susceptibility (Hagenimana and Ding 2005). Later report mentioned that extrusion cooking causes macromolecular degradation of starch leading to different α-amylase susceptibility profiles (Colonna et al. 1989).

Increasing GMS addition contents caused decrease of WSP of extrudates, while increasing LC and SSL addition contents caused increase of extrudates WSP. WSP of reform rice showed decrease for SR and GA added system but increase trend were found for SA added reform rice. Native proteins are denatured during extrusion. The forces which stabilize the tertiary and quaternary structures of the proteins are weakened by a combination of temperature and shear within the extruder. Previously hidden amino acid residues become exposed and are free to react with reducing sugars and other food components. The exposure of hydrophobic residues, such as phenylalanine and tyrosine, reduce the solubility of extruded protein in aqueous systems. The extrusion of starchy foods results in gelatinization partial or complete destruction of the crystalline structure and molecular fragmentation of starch polymers, as well as protein denaturation, and formation of complexes between starch and lipids and between protein and lipids (Colonna and Mercier 1983; Collier and O’Dea 1983; Mercier et al. 1980).

Hardness and adhesive properties

Increasing GMS contents caused increase of hardness for reform rice compared with control (159.05), but adhesive (absolute value) increased first and then decrease when GMS content went beyond 0.5%. While for LC and SSL, decreasing hardness and adhesive with more content addition were found. But for three thickener added system, extrudates become soft, as hardness decreased with these three thickeners content increasing. While for adhesive, it increased with thickeners increasing. The hardness of cooked instant rice was reported have positive correlation with density, which was related to the porosity of the structure of processed rice (Prasert and Suwannaporn 2009). It was said that hardness was depend on the structure characteristics (González et al. 2000; Robutti et al. 2002), and have a high correlation between hardness and sensory attributes of cooked rice (Park et al. 2001). Three thickeners addition resulting in a softer texture rehydrated rice.

Orthogonal optimum for complex reform rice (CRR)

From above results, added either emulsifier or thickener would cause different effects for the properties. Considering three indexes of instant rice mentioned above, we hold that combination of emulsifier and thickener with broken rice could optimize properties of rice extrude. In order to simplify the experiments, HR was selected as response value and orthogonal experiments for optimizing component were carried out as shown in Table 3. From the range analysis (k) results (Table 3) of orthogonal experiment, optimum conditions for extruding of CRR were: A1 (GMS 0.2%), B2(SA 0.5%), C2(SSL 0.8%), D2(SR 10%). GMS was the maximum influencing factor on the HR and SSL was the minimum effect factor.

Table 3.

Orthogonal experiments for HR

| Number | A(GMS) (%) | B (SA) (%) | C (SSL) (%) | D (SR) (%) | Hydration ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1(0.2) | 1(0.2) | 1(0.5) | 1(5) | 272 |

| 2 | 1(0.2) | 2(0.5) | 2(0.8) | 2(10) | 279 |

| 3 | 1(0.2) | 3(0.8) | 3(1.1) | 3(15) | 260 |

| 4 | 2(0.5) | 1(0.2) | 2(0.8) | 3(15) | 259 |

| 5 | 2(0.5) | 2(0.5) | 3(1.1) | 1(5) | 262 |

| 6 | 2(0.5) | 3(0.8) | 1(0.5) | 2(10) | 260 |

| 7 | 3(0.8) | 1(0.2) | 3(1.1) | 2(10) | 258 |

| 8 | 3(0.8) | 2(0.5) | 1(0.5) | 3(15) | 249 |

| 9 | 3(0.8) | 3(0.8) | 2(0.8) | 1(5) | 246 |

| K1 | 810 | 787 | 782 | 761 | |

| K2 | 781 | 799 | 781 | 797 | |

| K3 | 753 | 766 | 780 | 768 | |

| k1 | 270 | 262 | 260 | 254 | |

| k2 | 260 | 266 | 261 | 266 | |

| k3 | 251 | 255 | 260 | 256 | |

| R | 19.33 | 8.00 | 1.33 | 9.67 |

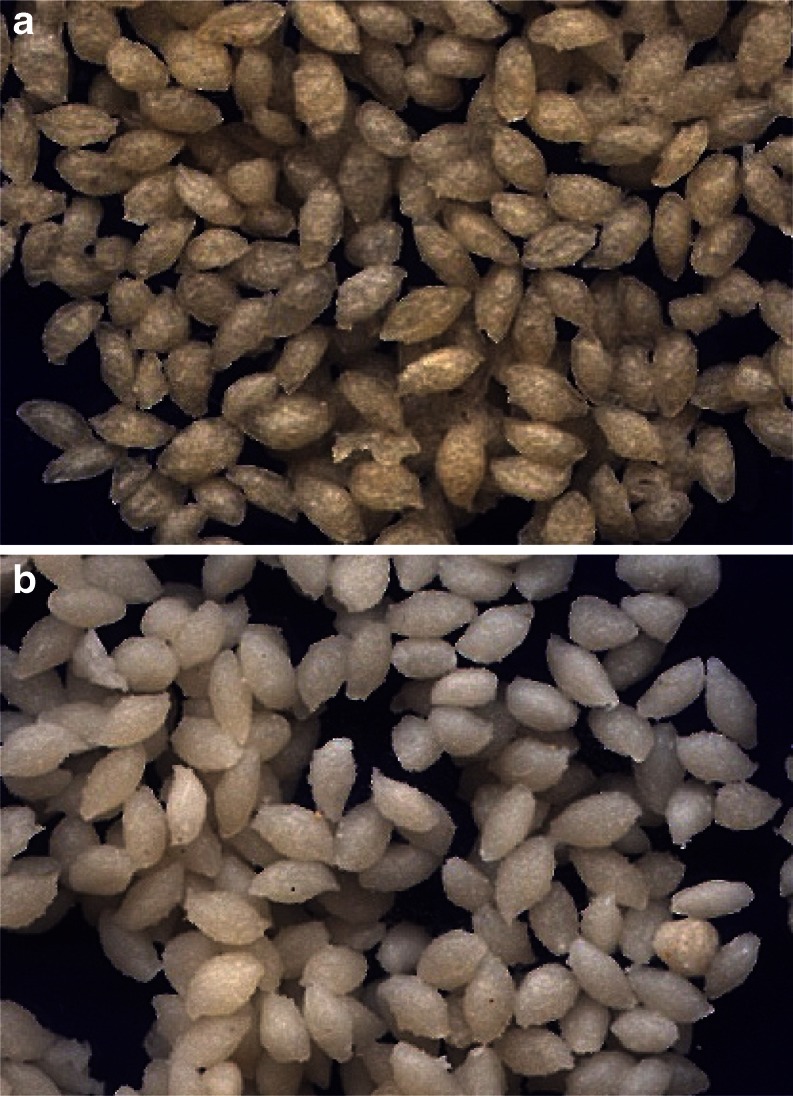

Properties of CRR and ICRR

CRR made from the orthogonal experiment prescription was shaped very well as shown in Fig. 3 (a), and physical–chemical properties of CRR were tested as shown in Table 4. Almost all of the properties were significantly improved compared with extrusion broken rice (control). But the DG was still not good enough for eating (71.9%). So, post cooking and drying were carried to make final instant complex reform rice (ICRR). For determining a proper rehydration time, ICRR was rehydrated for different time, and the textures were detected as shown in Table 5. We found that the hardness, viscosity, and chewiness decrease, as well as HR increase with rehydration time continually prolonging, while the springiness increase first and then decrease. So the suitable rehydration time was 5 min for ICRR.

Fig. 3.

Diagram of CRR (a) and ICRR (b)

Table 4.

Properties of CRR and ICRR

| Sample | DG (%) | BD (g/ml) | WSC (%) | WSP (%) | α-Amylase Sensibility(g reducing sugar/g) | WAI (g/g) | HR (%) | Hardness (g) | Adhesive (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 63.6 ± 1.12 | 0.71 ± 0.021 | 11.98 ± 0.146 | 2.52 ± 0.055 | 380.4 ± 2.63 | 4.61 ± 0.063 | 250 ± 1.25 | 159.05 ± 0.84 | −0.93 ± 0.011 |

| CRR | 71.9 ± 1.25 | 0.63 ± 0.019a | 12.64 ± 0.153a | 2.16 ± 0.053a | 391.6 ± 2..91a | 4.89 ± 0.071 | 268 ± 1.61a | 138.43 ± 0.58a | −0.99 ± 0.013a |

| ICRR | 93.3 ± 1.21a | 0.51 ± 0.018a | 12.83 ± 0.156a | 2.18 ± 0.049a | 400.3 ± 2.73a | 5.32 ± 0.072a | 296 ± 1.36a | 131.69 ± 0.73a | −0.94 ± 0.012 |

aMeans significant differences compared with control (p ≤ 0.05)

Table 5.

Texture properties of ICRR when hydration

| Hydration time (min) | HR (%) | Hardness (g) | Adhesive (g) | Springness | Chewing (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 172 | 330.47 | −1.63 | 0.68 | 169.78 |

| 5 | 245 | 213.64 | −1.72 | 0.76 | 133.37 |

| 7 | 269 | 166.07 | −0.92 | 0.79 | 68.31 |

| 10 | 348 | 120.76 | −0.52 | 0.64 | 38.31 |

The final ICRR was then mixed with equal volumes of hot water (80°) and product allowing same to rehydrate for 5 min, there was no excess water, and the rice particles were fully rehydrated having texture and eating qualities similar to that of cooked parboiled rice. Further soaking and drying were carried out to make ICRR. The produced ICRR were shaped very well as shown in Fig. 3(b). Sensory evaluation showed similar mouth feel and ripeness of ICRR as round shaped rice, and the elasticity was similar as long shaped rice (Table 6). The total score of ICRR was higher than commercial instant rice.

Table 6.

Sensory evaluation of ICRR

| Cooked long shaped rice | Cooked round shaped rice | Commercial instant rice | ICRR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.2 |

| Mouth feel | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.8 |

| Elasticity | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.7 |

| Viscosity | 4.5 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 4.2 |

| Ripeness | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.9 |

| Total score | 23.4 | 24.6 | 21.7 | 22.8 |

Conclusion

Emulsifiers and thickeners with different physical–chemical properties could provide different modifications for extrudates. Combined emulsifier and thickener together with broken rice could provide unique physical–chemical properties and acceptable texture and rehydration properties. Instant rice made from combination of emulsifier and thickener and broken rice, provide acceptable appearance, great texture quality, fine cooking rehydration and sensory acceptance. This effective make use of broken rice to enhance its economic value may be a potential method for development of ICRR. Extrusion parameters on properties of ICRR are under further studies to optimize quality.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation (grant no. BK2009069) and Jiangsu climing plan (BK2008003), we thank the projected supported by State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China (grant no. SKLF-MB-200804), we thank the subject of National Natural Science Foundation (20976070).

Contributor Information

Zheng Yu Jin, Email: jinlab2008@yahoo.com.

Jin Moon Kim, Email: jin.kim@fsis.usda.gov.

References

- An HZ, Jin ZY, Zhao XW, Lu JA. Effect of barrel temperature on physicochemical properties and texture of reformed rice. Food Sci Technol (Chinese) 2006;3:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Conway HF, Pfeifer VF, Griffin EL. Gelatinization of corn grits by roll- and extrusion-cooking. Cereal Sci Today. 1969;14:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar G, Srivastav PP, Das H. Effect of phosphate and citrate on quick-cooking rice. J Food Sci Technol India. 1989;26:286–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S, Hanna MA. Amylose-lipid complex formation during single-screw extrusion of various corn starches. Cereal Chem. 1994;71:587–593. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Sivakumar V, Chakraborty D. Changes in CIELab colour parameters due to extrusion of rice-greengram blend: a response surface approach. J Food Eng. 1997;32:125–131. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(97)00008-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RJ, Kadan RS, Champagne TE, Vinyard BT, Boykin D. Functional and digestive characteristics of extruded rice flour. Cereal Chem. 2001;78:131–137. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2001.78.2.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camire ME. Protein functionality modification by extrusion cooking. JAOCS. 1991;68:200–205. doi: 10.1007/BF02657770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camire ME, Camire A, Krumhar K. Chemical and nutritional changes in foods during extrusion. Food Sci Nutr. 1990;29:35–57. doi: 10.1080/10408399009527513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas JA, Carcia OF. Viscosity of solutions of xanthan/locust bean gum mixtures. J Sci Food Agri. 1999;79(25):31. [Google Scholar]

- Case SE, Hamann DD, Schwartz SJ. Effect of starch gelatinization on physical properties of extruded wheat- and corn based products. Cereal Chem. 1992;69:401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty P, Banerjee S. Optimization of extrusion process for production of expanded product from green gram and rice by response surface methodology. J Sci Indust Res. 2009;68:140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne T, Lyon G. Effects of post harvest processing on texture profile analysis of cooked rice. Cereal Chem. 1998;75:181–186. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.1998.75.2.181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charutigon C, Jitpupakdree J, Namsree P, Rungsardthong V. Effects of processing conditions and the use of modified starch and monoglyceride on some properties of extruded rice vermicelli. LWT. 2008;41:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheftel JC. Nutritional effects of extrusion-cooking. Food Chem. 1986;20:263–283. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(86)90096-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang BY, Johnson JA. Measurement of total and gelatinized starch by glucoamylase and o-toluidine reagent. Cereal Chem. 1977;54:429–435. [Google Scholar]

- Collier G, O’Dea K. The effect of coingestion of fat on the glucose, insulin, and gastric inhibitory polypeptide responses to carbohydrate and protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;37:94l–944l. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/37.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna P, Mercier C. Macromolecular modifications of manioc starch components by extrusion-cooking with and without lipids. Carbohyd Polym. 1983;3:87–108. doi: 10.1016/0144-8617(83)90001-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna P, Tayeb J, Mercier C (1989) Extrusion cooking of starch and starchy products. Extrusion Cooking Mercier C, Linko P, Harper JM (eds) Am Assoc Cereal Chem: St. Paul, MN. pp 247–319

- Conde-Petit B, Escher F. Complexation induced changes of rheological properties of starch systems at different moisture levels. J Rheol. 1995;39:1497–1518. doi: 10.1122/1.550612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deis RC. Functional ingredients from rice. Food Prod Design. 1997;7:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggum BO, Juliano BO, Ibabao MGB, Perez CM. Effect of extrusion cooking on nutritional value of rice flour. Food Chem. 1986;19:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(86)90073-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Dash AA, Gonzales R, Ciol M. Response surface methodology in the control of thermoplastic extrusion of starch. J Food Eng. 1983;2:129–152. doi: 10.1016/0260-8774(83)90023-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson AC, Krog N. Physical properties of amylose-monoglyceride complexes. J Cereal Sci. 1985;3:239–248. doi: 10.1016/S0733-5210(85)80017-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faubion JM, Hoseney RC. High-temperature short-time extrusion cooking of wheat starch and flour. II. Effect of protein and lipid on extrudates properties. Cereal Chem. 1982;59:533–537. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway GI, Biliaderis CG, Stanley DW. Properties and structure of amylose-glyceryl monostearate complexes formed in solution or on extrusion of wheat flour. J Food Sci. 1989;54:950–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1989.tb07920.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González RJ, Torres RL, Añón MC. Comparison of rice and corn cooking characteristics before and after extrusion. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 2000;9:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenimana A, Ding X. A comparative study on pasting and hydration properties of native rice starches and their mixtures. Cereal Chem. 2005;82:72–76. doi: 10.1094/CC-82-0070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartree EF. Determination of Protein: a modification of the Lowry method that gives a linear photometric response. Anal Biochem. 1972;48:422–427. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Hsieh F, Huff HE. Corn meal extrusion with emulsifier and soyabean fiber. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 1993;26:544–551. [Google Scholar]

- Jin ZY, Zhuang HN, Xie ZJ, Xu XM, Yang N, Su Q, Sang SY (2010) A forming die for extrusion instant rice, China patent No. 201020184349.

- Juliano BO (1996) Grain quality problems in Asia. Proceedings of an International Conference on Grain Drying in Asia. FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok, Thailand, 17–20 October 1995. ACIAR Proceedings No. 71. pp 15–22

- Juliano BO, Hicks PA. Rice functional properties and rice food products. Food Rev Int. 1996;12:71–103. doi: 10.1080/87559129609541068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang DF, He JF, Wang XC. The actuality and prospect of instant rice production in China. Cereal Process (in Chinese) 2007;32:40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur L, Singh N, Kaur K, Sungh B. Effect of mustard oil and process variables on extrusion behaviour of rice grits. J Food Sci Technol-Mysore. 2000;37:656–660. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AR, Ollett AL, Parker R, Smith AC. An experimental study of screw configuration effects in the twin-screw extrusion cooking of maize grits. J Food Eng. 1988;8:247–272. doi: 10.1016/0260-8774(88)90016-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malkki Y, Kervinen R, Olkku J, Linko P (1984) Effect of monoglycerides during cooking extrusion of wheat flour. Fats (Lipids) in baking and extrusion. Lipid forum Symp. Marcuse R (ed) SIK: Ghoteborg, Sweden. pp 130–137

- Margalli NAM, Lopenz MG. Water soluble carbohydrates and fructan structure patterns from Agave and Dasylirion species. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:7832–7839. doi: 10.1021/jf060354v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue N. Clean labels with rice. Prepared Foods. 1997;166:57. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier C, Feillet P. Modification of carbohydrate components by extrusion-cooking of cereal products. Cereal Chem. 1975;52:283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier C, Charbonniere R, Grebaut J, De la Gueriviere JF. Formation of amylose-lipid complexes by twin-screw extrusion cooking of manioc starch. Cereal Chem. 1980;57:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Meullenet JF. Relationship between sensory and instrumental textural profile attributes. J Sensory Stud. 1998;13:77–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.1998.tb00076.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Kimura N, Suzuki H, Miyashita Y, Nishio Y. Thermal and viscoelastic properties of alginate/poly(vinyl alcohol) crosslinked with calcium tetraborate. Carbohydr Polym. 1999;39:139–144. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00162-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan BS, Kong MS, Chen HH. Twin-screw extrusion for expanded rice products: processing parameters and formulation of extrudate properties. In: Kokini JL, Ho CT, Karue MV, editors. Food extrusion science and technology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1992. pp. 693–709. [Google Scholar]

- Panlasigui LN, Thompson LU, Juliano BO, Perez CM, Yiu SH, Greenberg GR. Rice varieties with similar amylose content differ in starch digestibility and glycemic response in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:871–877. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlasigui LN, Thompson LU, Juliano BO, Perez CM, Jenkins DJA, Yiu SH. Extruded rice noodles: starch digestibility and glycemic response of healthy and diabetic subjects with different habitual diets. Nutr Res. 1992;12:1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(05)80776-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park JK, Kim SS, Kim KO. Effect of milling ratio on sensory properties of cooked rice and on physicochemical properties of milled and cooked rice. Cereal Chem. 2001;78:151–156. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2001.78.2.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasert W, Suwannaporn P. Optimization of instant jasmine rice process and its physicochemical properties. J Food Eng. 2009;95:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puspitowati S, Driscoll RH. Effect of degree of gelatinisation on the rheology and rehydration kinetics of instant rice produced by freeze drying. Int J Food Prop. 2007;10:445–453. doi: 10.1080/10942910600871289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robutti JL, Borrás FS, González RJ, De Torres RL, Greef DM. Endosperm properties and extrusion cooking behavior of maize cultivars. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2002;35:663–669. doi: 10.1006/fstl.2002.0926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutenberg MW, Solarek D. Starch derivatives: production and uses. In: Whistler RL, BeMiller JN, Paschall EF, editors. Starch chemistry and technology, Chapter 10. New York: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 312–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu GH, Neumann PE, Walker CE. Effects of emulsifiers on physical properties of wheat flour extrudates with and without sucrose and shortening. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 1994;27:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer TF, Reimann S, Solms J, Eliasson AC, Asp NG. Influence of drum-drying and twin-screw extrusion cooking on wheat carbohydrates. II. Effect of lipids on physical properties, degradation and complex formation of starch in wheat flour. J Cereal Sci. 1986;4:249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0733-5210(86)80027-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semwal AD, Harma SGK, Arya SS. Flavor degradation in dehydrated convenience foods, changes in carbonyls in quick cooking rice and Bengal Gram. Food Chem. 1996;57:233–239. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(95)00208-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar TJ, Bandyopadhyay S. Process variables during single-screw extrusion of fish and rice-flour blends. J Food Process Preserv. 2005;29:151–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2005.00020.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DA, Rao RM, Liuzzo JA, Champagne E. Chemical treatment and process modification for producing improved quick-cooking rice. J Food Sci. 1985;50:926–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1985.tb12981.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi M. A new reagent for the determination of sugars by Michael Somogyi. J Biol Chem. 1945;160:61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Bhirud PR, Sosulski FW, Tyler RT. Pasta-like product from pea flour by twin-screw extrusion. J Food Sci. 1999;64:671–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1999.tb15108.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XL, Chen M, Xu H. The effects of food additives on α-instant rice. J ZhengZhou Institute Technol (in Chinese) 2001;22:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Ramaswamy HS, Boye J. Twin-screw extrusion of corn flour and soy protein isolate(SPI) blends: a response surface analysis. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Zavareze ER, Storck CR, Castro LAS, Schirmer MA, Dias ARG. Effect of heat-moisture treatment on rice starch of varying amylose content. Food Chem. 2010;12:36. [Google Scholar]