Abstract

Many different viruses are excreted by humans and animals and are frequently detected in fecal contaminated waters causing public health concerns. Classical bacterial indicator such as E. coli and enterococci could fail to predict the risk for waterborne pathogens such as viruses. Moreover, the presence and levels of bacterial indicators do not always correlate with the presence and concentration of viruses, especially when these indicators are present in low concentrations. Our research group has proposed new viral indicators and methodologies for determining the presence of fecal pollution in environmental samples as well as for tracing the origin of this fecal contamination (microbial source tracking). In this paper, we examine to what extent have these indicators been applied by the scientific community. Recently, quantitative assays for quantification of poultry and ovine viruses have also been described. Overall, quantification by qPCR of human adenoviruses and human polyomavirus JC, porcine adenoviruses, bovine polyomaviruses, chicken/turkey parvoviruses, and ovine polyomaviruses is suggested as a toolbox for the identification of human, porcine, bovine, poultry, and ovine fecal pollution in environmental samples.

1. Fecal Contamination of the Environment

Significant numbers of human microbial pathogens are present in urban sewage and may be considered environmental contaminants. Viruses, along with bacteria and protozoa in the intestine or in urine, are shed and transported through the sewer system. Although most pathogens can be removed by sewage treatment, many are discharged in the effluent and enter receiving waters. Point-source pollution enters the environment at distinct locations, through a direct route of discharge of treated or untreated sewage. Nonpoint sources of contamination are of significant concern with respect to the dissemination of pathogens and their indicators in the water systems. They are generally diffuse and intermittent and may be attributable to the run-off from urban and agricultural areas, leakage from sewers and septic systems, storm water, and sewer overflows [1–3].

Even in highly industrialized countries, viruses that infect humans prevail throughout the environment, causing public health concerns and leading to substantial economic losses. Many orally transmitted viruses produce subclinical infection and symptoms in only a small proportion of the population. However, some viruses may give rise to life-threatening conditions, such as acute hepatitis in adults, as well as severe gastroenteritis in small children and the elderly. The development of disease is related to the infective dose of the viral agent, the age, health, immunological and nutritional status of the infected individual (pregnancy, presence of other infections or diseases), and the availability of health care. Human pathogenic viruses in urban wastewater may potentially include human adenoviruses (HAdVs) and human polyomaviruses (HPyVs), which are detected in all geographical areas and throughout the year, and enteroviruses, noroviruses, rotaviruses, astroviruses, hepatitis A, and hepatitis E viruses, with variable prevalence in different geographical areas and/or periods of the year.

Moreover, with the venue of novel metagenomic techniques, new viruses are being discovered in the recent years that may be present in sewage and potentially contaminate the environment being transmitted to humans [4, 5].

Failures in controlling the quality of water used for drinking, irrigation, aquaculture, food processing, or recreational purposes have been associated to gastroenteritis and other diseases outbreaks in the population [6, 7]. Detailed knowledge about the contamination sources is needed for efficient and cost-effective management strategies to minimize fecal contamination in watersheds and foods, evaluation of the effectiveness of best management practices, and system and risk assessment as part of the water and food safety plans recommended by the World Health Organization [8, 9].

Microbial source tracking (MST) plays a very important role in enabling effective management and remediation strategies. MST includes a group of methodologies that aim to identify, and in some cases quantify, the dominant sources of fecal contamination in the environment and, more specifically, in water resources [10, 11]. Molecular techniques, specifically nucleic acid amplification procedures, provide sensitive, rapid, and quantitative analytical tools for studying specific pathogens, including new emergent strains and indicators. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is used to evaluate the microbiological quality of water [12] and the efficiency of virus removal in drinking and wastewater treatment plants [13, 14] and as a quantitative MST tool [15].

Between a wide range of MST candidate tools (reviewed in [16–18]), the use of human and animal viruses analyzed by qPCR as fecal indicators and MST tools will be the focus of this review.

2. Indicators of Fecal Contamination

Fecal pollution is a primary health concern in the environment, in water, and in food. The use of index microorganisms (whose presence points to the possible occurrence of a similar pathogenic organism) and indicator microorganisms (whose presence represents a failure affecting the final product) to assess the microbiological quality of waters or food is well established and has been practiced for almost a century [19].

Classic microbiological indicators such as fecal coliforms, Escherichia coli, and enterococci are the indicators most commonly analyzed to evaluate the level of fecal contamination. However, whether these bacteria are suitable indicators of the occurrence and concentration of pathogens such as viruses and protozoa cysts has been questioned for the following reasons: (i) indicator bacteria are more sensitive to inactivation through treatment processes and by sunlight than viral or protozoan pathogens; (ii) nonexclusive fecal source; (iii) ability to multiply in some environments; (iv) inability to identify the source of fecal contamination; (v) and low correlation with the presence of pathogens.

Various authors concluded that these indicators could fail to predict the risk for waterborne pathogens including viruses [20, 21]. Moreover, the levels of bacterial indicators do not always correlate with the concentration of viruses, especially when these indicators are present in low concentrations [22, 23].

Those viruses that are transmitted via contaminated food or water are typically stable because they lack the lipid envelopes that render other viruses vulnerable to environmental agents. Moreover since viruses usually respond to a host specific behavior, their detection may provide data for MST.

The fact that rapid methods are required and that, moreover, many pathogens cannot be cultivated in the laboratory has led to the development of new methodologies for the study of pathogens and new proposed indicators of fecal contamination in water and food. These are based on the implementation of molecular techniques that are rapid and sensitive but may pick up both infectious and noninfectious (dead) types. Quantitative PCR assays are being considered by US-EPA as a rapid analytical tool [24]. A review focused on the application of qPCR in the detection of microorganisms in water has been recently published by Botes and coworkers [25].

3. Quantification of Human and Animal Viruses as a Tool-Box for Determining Presence and Origin of Fecal Contamination in Waters

The high stability of viruses in the environment, their host specificity, persistent infections, and high prevalence of some viral infections throughout the year strongly support the use of rapid cost-effective sensitive molecular techniques for the identification and quantification of DNA viruses which can be used as complementary indicators of fecal and urine (hereinafter “fecal”) contamination and as MST tools. Detection of excreted DNA viruses may allow the development of cost-effective protocols with more accurate quantification of contaminating sources compared to RNA viruses. This is due to the greater accuracy of qPCR and its/their lower sensitivity to inhibitors, as reverse transcriptase is not used when amplifying DNA viruses.

Our research group has proposed new viral parameters and methodologies for the detection and quantification of human and animal DNA viruses as fecal indicators as well as MST tools. The first viral markers proposed were DNA viruses such as human and animal adenoviruses and polyomaviruses, and the assays developed for their detection were based on qualitative PCR [22, 81–84], and more recently qPCR techniques have been developed for not only detecting but also quantifying these viruses in environmental samples [28–31, 37].

Several research groups are currently using these parameters for analysis of viral contamination in water and as MST tools. One of the objectives of this review is to examine available data, so far, on the application of specific DNA viral indicators proposed many years ago (human adenoviruses, JC polyomavirus, porcine adenovirus, and bovine polyomavirus) and to evaluate its usefulness as quantitative tools for determining the origin of the fecal contamination in different countries.

Our group recently developed quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays for the quantification of chicken/turkey parvoviruses and ovine polyomaviruses which, together with those previously proposed for human, bovine and porcine fecal contamination, might constitute a tool box for studying the presence and origin of fecal contamination in environmental samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes used for the detection and quantification of viral indicators.

| Primers and probes | Virus | Positiona | Reference | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADF | Human adenovirus (HAdV) | 18869–18887 | CWTACATGCACATCKCSGG | |

| ADR | 18919–18937 | [26] | CRCGGGCRAAYTGCACCAG | |

| ADP1 | 18889–18916 | FAM-CCGGGCTCAGGTACTCCGAGGCGTCCT-BHQ1 | ||

|

| ||||

| JE3F | JC polyomavirus (JCPyV) | 4317–4339 | ATGTTTGCCAGTGATGATGAAAA | |

| JE3R | 4251–4277 | [27] | GGAAAGTCTTTAGGGTCTTCTACCTTT | |

| JE3P | 4313–4482 | FAM-AGGATCCCAACACTCTACCCCACCTAAAAAGA-BHQ1 | ||

|

| ||||

| QB-F1-1 | Bovine polyomavirus (BPyV) | 2122–2144 | CTAGATCCTACCCTCAAGGGAAT | |

| QB-R1-1 | 2177–2198 | [28] | TTACTTGGATCTGGACACCAAC | |

| QB-P1-2 | 2149–2174 | FAM-GACAAAGATGGTGTGTATCCTGTTGA-BHQ1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Q-PAdV-F | Porcine adenovirus (PAdV) | 20701–20718 | AACGGCCGCTACTGCAAG | |

| Q-PAdV-R | 20751–20768 | [29] | CACATCCAGGTGCCGC | |

| Q-PAdV-P | 20722–20737 | FAM-AGCAGCAGGCTCTTGAGG-BHQ1 | ||

|

| ||||

| qOv_F | Ovine polyomavirus (OPyV) | VP1b region | CAGCTGYAGACATTGTGG | |

| qOv_R | [30] | TCCAATCTGGGCATAAGATT | ||

| qOv_P | FAM-ATGATTACCAAGCCAGACAGTGGG-BHQ1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Q-PaV-F | Chicken/turkey parvovirus (ChPV/TuPV) | 3326–3345 | AGTCCACGAGATTGGCAACA | |

| Q-PaV-R | 3388–3407 | [31] | GCAGGTTAAAGATTTTCACG | |

| Q-PaV-Pr | 3356–3378 | 6FAM-AATTATTCGAGATGGCGCCCACG-BHQ1 | ||

aThe sequence positions are referred to strains J01917.1 (HAdV), NC_001699.1 (JCPyV), D13942 (BPyV), AJ237815 (PAdV), and GU214706 (ChPV/TuPV) from Genbank. bVP1: virion protein 1.

4. Treatment of Water Samples for Quantification of Viruses

A wide range of concentration methods have been described to recover viruses from water samples. These methods seek to concentrate viruses from large volumes (up to 1000 L) to smaller volumes ranging from 10 mL to 100 μL. Most of the methods used are based on adsorption-elution processes using membranes, filters, or matrixes like glass wool [58, 62, 85]. However, they are two-step methods that can be cumbersome and could hamper the simultaneous processing of a large number of samples. In order to eliminate the bottleneck associated with two-step methods, and when volumes of 1–10 L are analyzed, a one-step concentration is used in our laboratory. The method was initially designed to concentrate viruses from seawater samples [38]. Briefly, the method is based on the addition of a preflocculated skimmed-milk solution to the volume of sample to be concentrated. The pH is then adjusted to 3.5 with HCl 1 N and the sample is then stirred for 8 h to allow the viruses to be adsorbed into the skimmed-milk flocs at room temperature (RT). Then flocs are recovered by centrifugation at 8,000 ×g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatants are carefully removed without disturbing the sediment and the pellet is dissolved in phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). Preconditioning of the conductivity of the samples may be needed when applying the method to the concentration of viruses from freshwater samples [86] and a variation of the method has also been reported for sewage samples [87]. The method has proven to be efficient and reproducible, and by applying this method we have been able to concentrate virus from different water matrices [4, 52, 53, 77, 88, 89].

Enzymatic inhibition of the PCR is also a matter to have into consideration when testing environmental samples. Specific qPCR kits designed for working with environmental samples are available commercially. Analyzing neat but also diluted nucleic acids extraction is also recommended as well as introducing controls of inhibition in the assays performed [28].

Although some of these viruses, such as some types of human adenoviruses, may grow in cell culture, other viruses may not and/or cell culture assays take too long to produce rapid results. Some authors use nucleases treatment to destroy free genomes or genomes contained into damaged viral particles before nucleic acid extraction and qPCR in order to quantify only potentially infective viral particles [90–92].

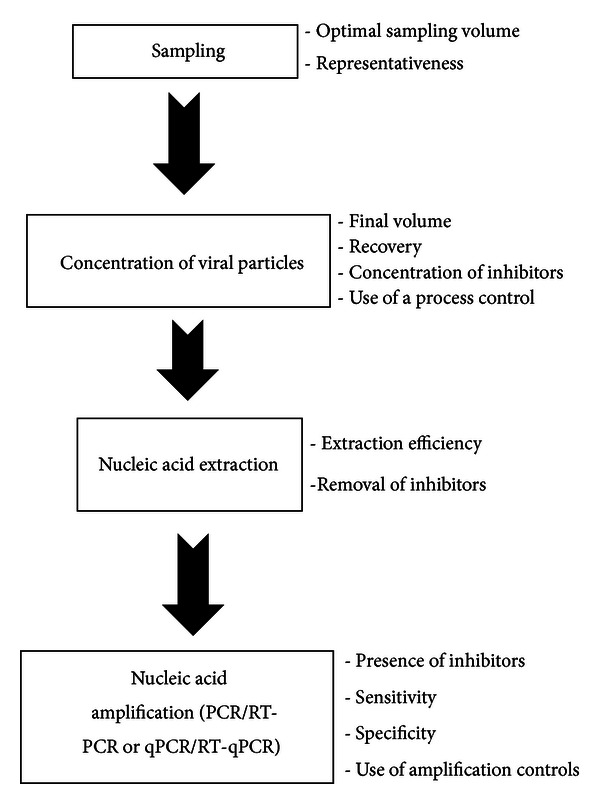

A flowchart summarizing the steps to follow to test an environmental sample for the presence of viral indicators is represented in Figure 1. Critical points to which attention should be paid are also summarized in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the method to detect and quantify viral indicators in the environment by PCR-based methods.

5. Quantitative PCR of Human Adenoviruses and Human Polyomavirus JC: A Tool to Determine Human Fecal Pollution in Water Matrices

Some viruses, such as human polyomaviruses (HPyVs) and adenoviruses (HAdVs), infect humans during childhood, thereby establishing, some of them, persistent infections. They are excreted in high quantities in the feces or urine of a high percentage of individuals.

The Adenoviridae family has a double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 35 000 base pairs (bp) surrounded by a 90–100 nm nonenveloped icosahedral shell with fiber-like projections from each vertex. Adenovirus infection may be caused by consumption of contaminated water or food, or by inhalation of aerosols from contaminated waters such as those used for recreational purposes. HAdV comprises 7 species with 52 types, which are responsible for both enteric illnesses and respiratory and eye infections [93].

Quantitative-based qPCR techniques used for the quantification of HAdV have been mainly designed to target the hexon protein and through degeneration of some nucleotides been able to amplify all HAdV types. In some cases and since HAdV types 40 and 41 are the ones etiologically associated to gastroenteritis as well as to a high prevalence in environmental samples, assays based on the sole detection of this two types have also been developed (Table 2).

Table 2.

HAdV quantification studies in environmental water matrices.

| Authors [Reference] | qPCR detection method [Reference] | Matrices analyzed | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| He and Jiang, 2005 [32] | He and Jiang, 2005 [32] | Sewage and coastal waters | Mean values in sewage 8.1E + 05 GC/L. Serotypes 1–5, 9, 16, 17, 19, 21, 28, 37, 40, 41 |

| Choi and Jiang, 2005 [33] | He and Jiang, 2005 [32] | River | 2–4 logs GC/L, 16% positive samples |

| Haramoto et al., 2005 [34] | Heim et al., 2003 [35] | River | 45% positive samples (29/64) |

| Albinana-Gimenez et al., 2006 [36] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | River and sewage | River used as a source of water presented 4E + 02 GC/L |

| Bofill-Mas et al., 2006 [37] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Sewage, effluent, and biosolids | High HAdV quantities in sewage, effluent, and biosolids. t90 and t99 of 60.9 and 132.3 days |

| Calgua et al., 2008 [38] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Seawater | New skimmed-milk flocculation method to concentrate, mean values of 1.26E + 03 GC/L |

| Albinana-Gimenez et al., 2009 [39] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | River and drinking-water treatment plants | 90% positive for river water, mean values 1E + 01–1E + 04 GC/L |

| Dong et al., 2010 [40] | Heim et al., 2003 [35], and by Ko et al., 2005 [41] | Sewage, drinking water, and river and recreational waters | Adenovirus detected from all water types. 10/10 positives in sewage (1.87E + 03–4.6E + 06 GC/L), 5/6 positives in recreational waters (1.70E + 01–1.19E + 03 GC/L) |

| Hamza et al., 2009 [42] | Heim et al., 2003 [35] | River and sewage | 97.5% positive river water samples (1.0E + 07–1.7E + 08 GC/L) |

| Ogorzaly et al., 2009 [43] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | River | 100% positive samples (1.0E + 04/l) |

| Bofill-Mas et al., 2010 [44] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Seawater | 3.2E + 03 GC/L, HAdV41 the most prevalent |

| Haramoto et al., 2010 [45] | Ko et al., 2005 [41] | River water | HAdV more prevalent (61.1%) than JCPyV (11.1%) |

| Jurzik et al., 2010 [46] | Heim et al., 2003 [35] | Surface waters | 96.3% positive samples (mean 2.9E + 03 GC/L and maximum of 7.3E + 05 GC/L) |

| Ogorzaly et al., 2010 [47] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Groundwater | HAdV was the most stable between MS2 and GA phages analyzed in groundwater |

| Rigotto et al., 2010 [48] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Seawater, lagoon brackish water, sewage, and drinking water | 64.2% positive values (54/84) |

| Schlindwein et al., 2010 [49] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Sewage, effluent, and sludge | 4.6E + 07–1.2E + 09 GC/L in sludge, 5E + 04–1.3E + 07 GC/L in sewage, and 3.1E + 05–5.4E + 05 GC/L in effluent |

| Aslan et al., 2011 [50] | Xagoraraki et al., 2007 [51] | Surface waters | 2–4 logs GC/L, 36% positives (HAdV 40/41) |

| Calgua et al., 2011 [52] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Seawater | Mean values 1–3 logs GC/L |

| Guerrero-Latorre et al., 2011 [53] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | River and groundwater | Low levels of HAdV in 4/16 groundwater samples |

| Hamza et al., 2011 [54] | Heim et al., 2003 [35] | River and sewage | 3E + 03 GC/L in river and 1.0E + 07–1.7E + 08 GC/L in sewage |

| Kokkinos et al., 2011 [55] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Sewage | 45.8% positive samples (22/48) in sewage. Main serotypes 8, 40, and 41 |

| Souza et al., 2011 [56] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Seawater | HAdV as the most prevalent in seawater |

| Wong and Xagoraraki, 2011 [57] | Heim et al., 2003 [35] | Manure and sewage sludge | Concentrations of E. coli and Enterococcus correlate to HAdV (P ≥ 0.05) in sludge samples |

| Wyn-Jones et al., 2011 [58] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Recreational water | 36.4% positive samples, more prevalent than noroviruses (9.4%) |

| Garcia et al., 2012 [59] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | River (source water) | 100% prevalence (1E + 07 GC/L) |

| Fongaro et al., 2012 [60] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Lagoon | 96% positive samples (46/48) |

| Rodriguez-Manzano et al., 2012 [13] | Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Raw sewage, secondary and terciary effluents | 100% positive samples for HAdV in all steps of the treatment. Removal of HAdV within primary and secondary treatments 1.03 log 10 (89%) and UV disinfection process 0.13 log 10 (11%) |

| Ye et al., 2012 [61] | Heim et al., 2003 [35] | River and drinking water | 100% positive samples (24/24). Mean values in river 2.28E + 04 GC/L |

Some of the more commonly used qPCR assays have been described by Hernroth et al. [26] with modifications [37] and Heim et al. [35]. We have previously compared both methods obtaining higher quantification in wastewater samples when applying the first one [37].

Table 2 summarizes quantitative HAdV data obtained by testing by qPCR different types of environmental samples.

Polyomaviruses are small and icosahedral viruses, with a circular double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 5000 bp that infect several species of vertebrates. JCPyV is ubiquitously distributed worldwide and antibodies against it are detected in over 80% of humans [94]. Kidney and bone marrow are sites of latent infection with JCPyV, which is excreted in the urine by healthy individuals [95, 96]. The pathogenicity of the virus is commonly associated with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in immunocompromised states, and it has attracted new attention due to JCPyV reactivation and pathogenesis in some patients of autoimmune diseases under treatment with immunomodulators [97, 98]. JCPyV is ubiquitously distributed and antibodies against JC virus are detected in over 80% of human population worldwide. BKPyV, the other classical human polyomavirus, causes nephropathy in renal transplant recipients and other immunosuppressed individuals. It is also excreted in urine and thus is present in wastewater, although its prevalence is lower than that of JCPyV [82], JCPyV is more frequently excreted than BKPyV. Is for these reasons that the specific polyomaviral marker in use in our laboratory is based on the quantification of JCPyV [37]. The assay developed by McQuaig et al. [63] that targets JC and BK human polyomaviruses (HPyVs) has also been extensively used (Table 3). We have tested both assays in diverse types of environmental samples obtaining equivalent results (data not shown). Results obtained when applying these assays to environmental samples support the applicability of the proposed indicators as molecular markers of the microbiological quality of water and they would fulfill the conditions defined for a human fecal/urine indicator. Harwood et al. [65], in a study using PCR, suggest that human polyomaviruses were the most specific human marker for MST among many other tools analyzed.

Table 3.

JCPyV (or HPyV) quantification studies in environmental water matrices.

| Authors [Reference] | qPCR detection method [Reference] | Matrices analyzed | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albinana-Gimenez et al., 2006 [36] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | Sewage and river | 100% positive samples in sewage (5/5) and river (9/9). Mean values 2.6E + 06 and 2.7E + 01 GC/L, respectively |

| Bofill-Mas et al., 2006 [37] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | Sewage, effluent, and sludge | 99% positive samples. T99 of 127.3 days |

| Albinana-Gimenez et al., 2009 [62] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | River | 48% positive samples in river water |

| Albinana-Gimenez et al., 2009 [39] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | River and drinking-water treatment plant (DWTP) | 48% positive samples (different steps of the DWTP ) with mean values 1E + 01 to 1E + 03 GC/L |

| McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Sewage, fresh to marine water, animal waste | Mean values in sewage 3.0E + 07 GC/L |

| Hamza et al., 2009 [42] | Biel et al., 2000 [64] | River | Detected (as JC and BK) in 97.5% of the samples |

| Harwood et al., 2009 [65] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | River, animal feces, and seawater | No detection of HPyV in animal feces No correlation with Enterococcus 100% host specificity |

| Ahmed et al., 2009 [66] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Sewage | |

| Abdelzaher et al., 2010 [67] |

McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Seawater | The FIB levels exceeded regulatory guidelines during one event, and this was accompanied by detection of HPyVs and pathogens |

| Ahmed et al., 2010 [68] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Sewage and seawater | JC and BK are highly host-specific viruses and high titers are found in sewage |

| Bofill-Mas et al., 2010 [44] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | River and sewage | Sewage ranges from 8.3E + 04 to 8.5E + 06 GC/L (7/7) River ranges from 4.4E + 03 to 1.4E + 04 GC/L (7/7) |

| Fumian et al., 2010 [69] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | Sewage and effluent | JCPyV detected in 96% and 43% of raw and treated sewage, respectively |

| Haramoto et al., 2010 [45] | Pal et al., 2006 [27] | River | JCPyV prevalence 11.1%, BKPyV not detected |

| Jurzik et al., 2010 [46] | Biel et al., 2000 [64], and modified by Hamza et al., 2009 [42] | River | 68.8% were positive for HPyV |

| Gibson et al., 2011 [70] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | River and drinking water | HPyV were detected in one groundwater, three-surface water, and one drinking-water sample. No correlation with FIB |

| Hamza et al., 2011 [54] | Biel et al., 2000 [64] | River and sewage | River 5.0E + 01–3.8E + 04 GC/L, sewage 5.7E + 07–5.7E + 08 GC/L |

| Hellein et al., 2011 [71] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Seawater, sewage, and animal feces | Presence of HPyV in all sewage samples and in one freshwater sample |

| Kokkinos et al., 2011 [55] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Sewage | 68.8% positive values (33/48) for JC and BK |

| Wong and Xagoraraki, 2011 [72] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Manure sewage and sludge | HPyV concentrations were slightly lower than Escherichia coli and Enterococcus (P < 0.05) |

| Chase et al., 2012 [73] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Recreational waters | HPyV detection near septic systems |

| Fongaro et al., 2012 [60] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Lagoon | 21% positive samples |

| Gordon et al., 2013 [74] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Estuarine to marine waters and sewage spills | HPyV demonstrated the ability to detect domestic sewage contamination in water |

| Rodriguez-Manzano et al., 2012 [13] |

Hernroth et al., 2002 [26] | Raw sewage, secondary and tertiary effluent | JCPyV in raw sewage (6/6) with an average concentration of 5.44E + 05 GC/L. Not detected in the tertiary effluent. |

| McQuaig et al., 2012 [75] | McQuaig et al., 2009 [63] | Seawater | Mean values 5E + 02 to 3.55E + 05 GC/L |

| Staley et al., 2012 [76] | Staley et al., 2012 [76] | Sewage, river | 100% and 64% positive samples of sewage and river samples, respectively |

Overall, studies show that HAdV has the highest prevalence in environmental samples while JC polyomavirus (or HPyV) qPCR assays have the best specificity. For this reason we propose the analysis of both viruses, HAdV and JCPyV, to determine human fecal pollution of environmental samples (Table 1). It is important to point out that the proposed markers are selected for its stable excretion all over the year in all geographical areas. However, in some cases the numbers of specific pathogens in high excretion periods, such as rotaviruses or noroviruses, may exceed the numbers of HAdV [99].

6. Quantitative PCR of Animal Viruses: Determining Porcine, Bovine, Poultry, or Ovine Pollution Origin in Environmental Samples

Since porcine adenoviruses (PAdVs) and bovine polyomaviruses (BPyVs) were proposed as porcine and bovine fecal indicators [83, 84], several studies have shown that these viruses are widely disseminated in the swine and bovine population, respectively, although they do not produce clinically severe diseases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quantification of PAdV and BPyV in environmental samples.

| Authors [Reference] | qPCR detection method [Reference] | Matrices analyzed | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hundesa et al., 2009 [29] | PAdV, Hundesa et al., 2009 [29] | River, slaughterhouse, and urban sewage | 100% positive samples in slaughterhouse sewage (1.56 + 03 GC/L) and 100% in river (8.38 GC/L) |

| Hundesa et al., 2010 [28] | BPyV, Hundesa et al., 2010 [28] | River, slaughterhouse, and urban sewage | 91% positive samples in slaughterhouse sewage (2.95E + 03 GC/L) and 50% in river (3.06E + 02 GC/L) |

| Bofill-Mas et al., 2011 [77] | BPyV, Hundesa et al., 2010 [28] | Groundwater | 1/4 well water positive for BPyV (7.74 × 102 GC/L) |

| Wolf et al., 2010 [78] | PAdV, Wolf et al., 2010 [78] | River | 50% positive river water samples |

| Wong and Xagoraraki, 2011 [57] | BPyV, Wong and Xagoraraki 2011 [57] | Sewage | 100% positive for manure and wastewater, 5.6% positive for feces samples |

| Viancelli et al., 2012 [79] | PAdV, Hundesa et al., 2009 [29] | Manure | 66% of the samples collected in the SMTS and in 78% of the samples collected in the DU system |

| Viancelli et al., 2013 [80] | PAdV, Hundesa et al., 2009 [29] | Manure | PAdV were more prevalent than other viruses and can possibly be considered as indicators of manure contamination |

In 2009 and 2010, quantitative assays for the quantification of these viruses were described to be applied to environmental samples [28, 29].

The results of these studies showed that BPyV and PAdV were quantified in a high percentage of the samples in which their presence was potentially expected, whereas samples used as negative templates were negative. BPyV and PAdV were found to be distributed in slaughterhouse wastewater and sludge, and in river water from farm-contaminated areas, but not in urban wastewater collected in areas without agricultural activities nor in hospital wastewater [28, 84, 100]. These results support the specificity and applicability of the BPyV and PAdV assays for tracing bovine and porcine fecal contamination in environmental samples, respectively. Quantitative data present in the literature on the presence of these viruses in environmental samples are summarized in Table 4.

Recently, the quantification of chicken/turkey parvoviruses (Ch/TuPVs), highly prevalent in healthy chickens and turkey's from different geographical areas [101–103], has been reported as a candidate MST tool for the identification of poultry originated pollution in environmental samples [31]. A quantitative PCR assay targeting the Ch/TuPV VP1/VP2 region was developed (Table 1) and the viruses detected in 73% of pooled chicken stool samples from the different geographical areas tested (Spain, Greece, and Hungary). Also, chicken slaughterhouse raw wastewater samples and raw urban sewage samples downstream of the slaughterhouse tested positive. The specificity of the designed assays was further studied by testing a wide selection of animal samples (feline, canine, porcine, bovine, ovine, duck, and gull) as well as by testing hospital sewage and urban sewage from areas without poultry industry. These results indicate that Ch/TuPVs may be suitable viral indicators of poultry fecal contamination and that these viruses are being disseminated into the environment.

More recently, the quantification of ovine polyomavirus (OPyV), a newly described virus, has been reported as a candidate tool to identify an ovine fecal/urine origin of fecal pollution [30]. Putative OPyV DNA was amplified from ovine urine and faecal samples using a broad-spectrum nested PCR (nPCR) designed by Johne and coworkers [104]. A specific qPCR assay (Table 1) has been developed and applied to faecal and environmental samples, including sheep slurries, slaughterhouse wastewater effluents, urban sewage, and river water samples. Successful quantification of OPyV was achieved in sheep urine samples, sheep slaughterhouse wastewater, and downstream sewage effluents. The assay was specific and was negative in samples of human, bovine, goat, swine, and chicken origin. Ovine faecal pollution was detected in river water samples by applying the designed methods. These results provide a quantitative tool for the analysis of OPyV as a suitable viral indicator of sheep faecal contamination that may be present in the environment.

7. Conclusions

Specific qPCR assays for the quantification of DNA viruses have been proposed as specific and sensitive assays to quantify human, porcine, bovine polyomavirus, poultry, and ovine fecal contamination in environmental samples.

Quantitative data is being accumulated on the presence and concentration of the proposed viral markers in environmental samples in many different countries. Future efforts should be directed towards developing standard procedures and reference materials for a reproducible application of these tools.

Meanwhile, these assays can be used to evaluate the microbiological quality of water and the efficiency of pathogen removal in drinking and wastewater treatment plants and in MST studies.

References

- 1.Brownell MJ, Harwood VJ, Kurz RC, McQuaig SM, Lukasik J, Scott TM. Confirmation of putative stormwater impact on water quality at a Florida beach by microbial source tracking methods and structure of indicator organism populations. Water Research. 2007;41(16):3747–3757. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart JR, Gast RJ, Fujioka RS, et al. The coastal environment and human health: microbial indicators, pathogens, sentinels and reservoirs. Environmental Health. 2008;7(2, article S3) doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-7-S2-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bercu B, Van De Werfhorst LC, Murray JL, Holden PA. Sewage exfiltration as a source of storm drain contamination during dry weather in urban watersheds. Environmental Science and Technology. 2011;45(17):7151–7157. doi: 10.1021/es200981k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantalupo PG, Calgua B, Zhao G, et al. Raw sewage harbors diverse viral populations. mBio. 2011;2(5):180–192. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00180-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng TF, Marine R, Wang C, et al. High variety of known and new RNA and DNA viruses of diverse origins in untreated sewage. Journal of Virology. 2012;86(22):12161–12175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00869-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinclair RG, Jones EL, Gerba CP. Viruses in recreational water-borne disease outbreaks: a review. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2009;107(6):1769–1780. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mena KD, Gerba CP. Waterborne adenovirus. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2009;198:133–167. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09647-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. 3rd edition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.USEPA. EPA/600/R-05/064. USA, Environmental Protection Agency; 2005. Microbial source tracking guide document. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field KG, Cotruvo JA, Dufour A, et al. Faecal Source Identification in Waterborne Zoonoses: Identification, Causes and Control. London, UK: IWA Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong TT, Lipp EK. Enteric viruses of humans and animals in aquatic environments: health risks, detection, and potential water quality assessment tools. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2005;69(2):357–371. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.357-371.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girones R, Ferrús MA, Alonso JL, et al. Molecular detection of pathogens in water—the pros and cons of molecular techniques. Water Research. 2010;44(15):4325–4339. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Manzano J, Alonso JL, Ferrús MA, et al. Standard and new faecal indicators and pathogens in sewage treatment plants, microbiological parameters for improving the control of reclaimed water. Water Science and Technology. 2012;66(12):2517–2523. doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francy DS, Stelzer EA, Bushon RN, et al. Comparative effectiveness of membrane bioreactors, conventional secondary treatment, and chlorine and UV disinfection to remove microorganisms from municipal wastewaters. Water Research. 2012;46(13):4164–4178. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoeckel DM, Harwood VJ. Performance, design, and analysis in microbial source tracking studies. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(8):2405–2415. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02473-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott TM, Rose JB, Jenkins TM, Farrah SR, Lukasik J. Microbial source tracking: current methodology and future directions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2002;68(12):5796–5803. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5796-5803.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roslev P, Bukh AS. State of the art molecular markers for fecal pollution source tracking in water. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;89(5):1341–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-3080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong K, Fong TT, Bibby K, Molina M. Application of enteric viruses for fecal pollution source tracking in environmental waters. Environmental International. 2012;15(45):151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medema GJ, Hoogenboezem W, Van Der Veer AJ, Ketelaars HAM, Hijnen WAM, Nobel PJ. Quantitative risk assessment of Cryptosporidium in surface water treatment. Water Science and Technology. 2003;47(3):241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerba CP, Goyal SM, LaBelle RL, Cech I, Bodgan GF. Failure of indicator bacteria to reflect the occurrence of enteroviruses in marine waters. American Journal of Public Health. 1979;69(11):1116–1119. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.11.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipp EK, Farrah SA, Rose JB. Assessment and impact of microbial fecal pollution and human enteric pathogens in a coastal community. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2001;42(4):286–293. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(00)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pina S, Puig M, Lucena F, Jofre J, Girones R. Viral pollution in the environment and in shellfish: human adenovirus detection by PCR as an index of human viruses. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64(9):3376–3382. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3376-3382.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contreras-Coll N, Lucena F, Mooijman K, et al. Occurrence and levels of indicator bacteriophages in bathing waters throughout Europe. Water Research. 2002;36(20):4963–4974. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(02)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanks OC, Sivaganesan M, Peed L, et al. Interlaboratory comparison of real-time PCR protocols for quantification of general fecal indicator bacteria. Environmental Science and Technology. 2012;46(2):945–953. doi: 10.1021/es2031455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Botes M, de Kwaadsteniet M, Cloete TE. Application of quantitative PCR for the detection of microorganisms in water. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2013;405(1):91–108. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6399-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernroth BE, Conden-Hansson AC, Rehnstam-Holm AS, Girones R, Allard AK. Environmental factors influencing human viral pathogens and their potential indicator organisms in the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis: the first Scandinavian report. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2002;68(9):4523–4533. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4523-4533.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pal A, Sirota L, Maudru T, Peden K, Lewis AM. Real-time, quantitative PCR assays for the detection of virus-specific DNA in samples with mixed populations of polyomaviruses. Journal of Virological Methods. 2006;135(1):32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hundesa A, Bofill-Mas S, Maluquer de Motes C, et al. Development of a quantitative PCR assay for the quantitation of bovine polyomavirus as a microbial source-tracking tool. Journal of Virological Methods. 2010;163(2):385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hundesa A, Maluquer de Motes C, Albinana-Gimenez N, et al. Development of a qPCR assay for the quantification of porcine adenoviruses as an MST tool for swine fecal contamination in the environment. Journal of Virological Methods. 2009;158(1-2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusiñol M, Carratalà A, Hundesa A, et al. Description of a novel viral tool to identify and quantify ovine faecal polluion in the environment. Science of the Total Environment. 2013;458-460:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carratalà A, Rusinol M, Hundesa A, et al. A novel tool for specific detection and quantification of chicken/turkey parvoviruses to trace poultry fecal contamination in the environment. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(20):7496–7499. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01283-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He JW, Jiang S. Quantification of enterococci and human adenoviruses in environmental samples by real-time PCR. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(5):2250–2255. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2250-2255.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi S, Jiang SC. Real-time PCR quantification of human adenoviruses in urban rivers indicates genome prevalence but low infectivity. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(11):7426–7433. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7426-7433.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haramoto E, Katayama H, Oguma K, Ohgaki S. Application of cation-coated filter method to detection of noroviruses, enteroviruses, adenoviruses, and torque teno viruses in the Tamagawa River in Japan. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71(5):2403–2411. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2403-2411.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heim A, Ebnet C, Harste G, Pring-Åkerblom P. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. Journal of Medical Virology. 2003;70(2):228–239. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albinana-Gimenez N, Clemente-Casares P, Bofill-Mas S, Hundesa A, Ribas F, Girones R. Distribution of human polyomaviruses, adenoviruses, and hepatitis E virus in the environment and in a drinking-water treatment plant. Environmental Science and Technology. 2006;40(23):7416–7422. doi: 10.1021/es060343i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bofill-Mas S, Albinana-Gimenez N, Clemente-Casares P, et al. Quantification and stability of human adenoviruses and polyomavirus JCPyV in wastewater matrices. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(12):7894–7896. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00965-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calgua B, Mengewein A, Grunert A, et al. Development and application of a one-step low cost procedure to concentrate viruses from seawater samples. Journal of Virological Methods. 2008;153(2):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albinana-Gimenez N, Miagostovich MP, Calgua B, Huguet JM, Matia L, Girones R. Analysis of adenoviruses and polyomaviruses quantified by qPCR as indicators of water quality in source and drinking-water treatment plants. Water Research. 2009;43(7):2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong Y, Kim J, Lewis GD. Evaluation of methodology for detection of human adenoviruses in wastewater, drinking water, stream water and recreational waters. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2010;108(3):800–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ko G, Jothikumar N, Hill VR, Sobsey MD. Rapid detection of infectious adenoviruses by mRNA real-time RT-PCR. Journal of Virological Methods. 2005;127(2):148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamza IA, Jurzik L, Stang A, Sure K, Überla K, Wilhelm M. Detection of human viruses in rivers of a densly-populated area in Germany using a virus adsorption elution method optimized for PCR analyses. Water Research. 2009;43(10):2657–2668. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogorzaly L, Tissier A, Bertrand I, Maul A, Gantzer C. Relationship between F-specific RNA phage genogroups, faecal pollution indicators and human adenoviruses in river water. Water Research. 2009;43(5):1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bofill-Mas S, Calgua B, Clemente-Casares P, et al. Quantification of human adenoviruses in European recreational waters. Food and Environmental Virology. 2010;2(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haramoto E, Kitajima M, Katayama H, Ohgaki S. Real-time PCR detection of adenoviruses, polyomaviruses, and torque teno viruses in river water in Japan. Water Research. 2010;44(6):1747–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jurzik L, Hamza IA, Puchert W, Überla K, Wilhelm M. Chemical and microbiological parameters as possible indicators for human enteric viruses in surface water. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2010;213(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogorzaly L, Bertrand I, Paris M, Maul A, Gantzer C. Occurrence, survival, and persistence of human adenoviruses and F-specific RNA phages in raw groundwater. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(24):8019–8025. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00917-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rigotto C, Victoria M, Moresco V, et al. Assessment of adenovirus, hepatitis A virus and rotavirus presence in environmental samples in Florianopolis, South Brazil. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2010;109(6):1979–1987. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlindwein AD, Rigotto C, Simões CMO, Barardi CRM. Detection of enteric viruses in sewage sludge and treated wastewater effluent. Water Science and Technology. 2010;61(2):537–544. doi: 10.2166/wst.2010.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aslan A, Xagoraraki I, Simmons FJ, Rose JB, Dorevitch S. Occurrence of adenovirus and other enteric viruses in limited-contact freshwater recreational areas and bathing waters. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2011;111(5):1250–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xagoraraki I, Kuo DHW, Wong K, Wong M, Rose JB. Occurrence of human adenoviruses at two recreational beaches of the great lakes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2007;73(24):7874–7881. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calgua B, Barardi CRM, Bofill-Mas S, Rodriguez-Manzano J, Girones R. Detection and quantitation of infectious human adenoviruses and JC polyomaviruses in water by immunofluorescence assay. Journal of Virological Methods. 2011;171(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guerrero-Latorre L, Carratala A, Rodriguez-Manzano J, Calgua B, Hundesa A, Girones R. Occurrence of water-borne enteric viruses in two settlements based in Eastern Chad: analysis of hepatitis E virus, hepatitis A virus and human adenovirus in water sources. Journal of Water Health. 2011;9(3):515–524. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamza IA, Jurzik L, Überla K, Wilhelm M. Methods to detect infectious human enteric viruses in environmental water samples. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2011;214(6):424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kokkinos PA, Ziros PG, Mpalasopoulou G, Galanis A, Vantarakis A. Molecular detection of multiple viral targets in untreated urban sewage from Greece. Virology Journal. 2011;8, article 195 doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Souza DS, Ramos AP, Nunes FF, et al. Evaluation of tropical water sources and mollusks in southern Brazil using microbiological, biochemical, and chemical parameters. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2011;76(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong K, Xagoraraki I. Evaluating the prevalence and genetic diversity of adenovirus and polyomavirus in bovine waste for microbial source tracking. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;90(4):1521–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3156-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wyn-Jones AP, Carducci A, Cook N, et al. Surveillance of adenoviruses and noroviruses in European recreational waters. Water Research. 2011;45(3):1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia LA, Viancelli A, Rigotto C, et al. Surveillance of human and swine adenovirus, human norovirus and swine circovirus in water samples in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Journal Water of Health. 2012;10(3):445–452. doi: 10.2166/wh.2012.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fongaro G, Nascimento MA, Viancelli A, Tonetta D, Petrucio MM, Barardi CR. Surveillance of human viral contamination and physicochemical profiles in a surface water lagoon. Water and Science Technology. 2012;66(12):2682–2687. doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ye XY, Ming X, Zhang YL, et al. Real-time PCR detection of enteric viruses in source water and treated drinking water in Wuhan, China. Current Microbiology. 2012;65(3):244–253. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Albinana-Gimenez N, Clemente-Casares P, Calgua B, Huguet JM, Courtois S, Girones R. Comparison of methods for concentrating human adenoviruses, polyomavirus JC and noroviruses in source waters and drinking water using quantitative PCR. Journal of Virological Methods. 2009;158(1-2):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McQuaig SM, Scott TM, Lukasik JO, Paul JH, Harwood VJ. Quantification of human polyomaviruses JC virus and BK Virus by TaqMan quantitative PCR and comparison to other water quality indicators in water and fecal samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(11):3379–3388. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02302-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biel SS, Held TK, Landt O, et al. Rapid quantification and differentiation of human polyomavirus DNA in undiluted urine from patients after bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38(10):3689–3695. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3689-3695.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harwood VJ, Brownell M, Wang S, et al. Validation and field testing of library-independent microbial source tracking methods in the Gulf of Mexico. Water Research. 2009;43(19):4812–4819. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahmed W, Goonetilleke A, Powell D, Chauhan K, Gardner T. Comparison of molecular markers to detect fresh sewage in environmental waters. Water Research. 2009;43(19):4908–4917. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abdelzaher AM, Wright ME, Ortega C, et al. Presence of pathogens and indicator microbes at a non-point source subtropical recreational marine beach. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(3):724–732. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02127-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahmed W, Goonetilleke A, Gardner T. Human and bovine adenoviruses for the detection of source-specific fecal pollution in coastal waters in Australia. Water Research. 2010;44(16):4662–4673. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fumian TM, Guimarães FR, Vaz BJP, et al. Molecular detection, quantification and characterization of human polyomavirus JC from waste water in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Journal of Water and Health. 2010;8(3):438–445. doi: 10.2166/wh.2010.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gibson KE, Opryszko MC, Schissler JT, Guo Y, Schwab KJ. Evaluation of human enteric viruses in surface water and drinking water resources in southern Ghana. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;84(1):20–29. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hellein KN, Battie C, Tauchman E, Lund D, Oyarzabal OA, Lepo JE. Culturebased indicators of fecal contamination and molecular microbial indicators rarely correlate with Campylobacter spp. in recreational waters. Journal of Water Health. 2011;9(4):695–707. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wong K, Xagoraraki I. A perspective on the prevalence of DNA enteric virus genomes in anaerobic-digested biological wastes. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2011;184(8):5009–5016. doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chase E, Hunting J, Staley C, Harwood VJ. Microbial source tracking to identify human and ruminant sources of faecal pollution in an ephemeral Florida river. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2012;113(6):1396–1406. doi: 10.1111/jam.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gordon KV, Brownell M, Wang SY, et al. Relationship of human-associated microbial source tracking markers with Enterococci in Gulf of Mexico waters. Water Research. 2013;47(3):996–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McQuaig SM, Griffith J, Harwood VJ. The association of fecal indicator bacteria with human viruses and microbial source tracking markers at coastal beaches impacted by nonpoint source pollution. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(18):6423–6432. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00024-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Staley C, Gordon KV, Schoen ME, Harwood VJ. Performance of two quantitative PCR methods for microbial source tracking of human sewage and implications for microbial risk assessment in recreational waters. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(20):7317–7326. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01430-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bofill-Mas S, Hundesa A, Calgua B, Rusiñol M, de Motes CM, Girones R. Costeffective method for microbial source tracking using specific human and animal viruses. Journal of Visual Experiments. 2011;(58) doi: 10.3791/2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wolf S, Hewitt J, Greening GE. Viral multiplex quantitative PCR assays for tracking sources of fecal contamination. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(5):1388–1394. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02249-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Viancelli A, Garcia LAT, Kunz A, Steinmetz R, Esteves PA, Barardi CRM. Detection of circoviruses and porcine adenoviruses in water samples collected from swine manure treatment systems. Research in Veterinary Science. 2012;93(1):538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Viancelli A, Kunz A, Steinmetz RLR, et al. Performance of two swine manure treatment systems on chemical composition and on the reduction of pathogens. Chemosphere. 2013;90(4):1539–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Puig M, Jofre J, Lucena F, Allard A, Wadell G, Girones R. Detection of adenoviruses and enteroviruses in polluted waters by nested PCR amplification. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1994;60(8):2963–2970. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2963-2970.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bofill-Mas S, Pina R S. Documenting the epidemiologic patterns of polyomaviruses in human populations by studying their presence in urban sewage. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(1):238–245. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.1.238-245.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Motes CM, Clemente-Casares P, Hundesa A, Martín M, Girones R. Detection of bovine and porcine adenoviruses for tracing the source of fecal contamination. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70(3):1448–1454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1448-1454.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hundesa A, Maluquer De Motes C, Bofill-Mas S, Albinana-Gimenez N, Girones R. Identification of human and animal adenoviruses and polyomaviruses for determination of sources of fecal contamination in the environment. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(12):7886–7893. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01090-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vilaginès P, Sarrette B, Husson G, Vilaginès R. Glass wool for virus concentration at ambient water pH level. Water Sience and Technology. 1993;27(3-4):299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Calgua B, Rodriguez-Manzano J, Hundesa A, et al. New Methods from the concentration of viruses from urban sewage using quantitative PCR. Journal of Virological Methods. 2013;187(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Calgua B, Fumian T, Rusiñol M, et al. Detection and quantification of classic and emerging viruses by skimmed-milk flocculation and PCR in river water from two geographical areas. Water Research. 2013;47(8):2797–2810. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bofill-Mas S, Rodriguez-Manzano J, Calgua B, Carratala A, Girones R. Newly described human polyomaviruses Merkel Cell, KI and WU are present in urban sewage and may represent potential environmental contaminants. Virology Journal. 2010;7, article 141 doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Calgua B, Rodriguez-Manzano J, Hundesa A, et al. New methods for the concentration of viruses from urban sewage using quantitative PCR. Journal of Virological Methods. 2013;187(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nuanualsuwan S, Cliver DO. Pretreatment to avoid positive RT-PCR results with inactivated viruses. Journal of Virological Methods. 2002;104(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pecson BM, Martin LV, Kohn T. Quantitative PCR for determining the infectivity of bacteriophage MS2 upon inactivation by heat, UV-B radiation, and singlet oxygen: advantages and limitations of an enzymatic treatment to reduce false-positive results. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(17):5544–5554. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00425-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Abreu-Correa A, Carratala A, Monte-Baradi CR, Calvo M, Girones R, Bofill-Mas S. Comparative inactivation of Murine Norovirus, Human Adenovirus, and JC Polyomavirus by chlorine in seawater. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012;78(18):6450–6457. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01059-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jiang SC. Human adenoviruses in water: occurrence and health implications: a critical review. Environmental Science and Technology. 2006;40(23):7132–7140. doi: 10.1021/es060892o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weber T, Klapper PE, Cleator GM, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of JC virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid: A Quality Control Study. Journal of Virological Methods. 1997;69(1-2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kitamura T, Aso Y, Kuniyoshi N, Hara K, Yogo Y. High incidence of urinary JC virus excretion in nonimmunosuppressed older patients. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1990;161(6):1128–1133. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koralnik IJ, Boden D, Mai VX, Lord CI, Letvin NL. JC virus DNA load in patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurology. 1999;52(2):253–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Berger JR, Houff SA, Major EO. Monoclonal antibodies and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. mAbs. 2009;1(6):583–589. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.6.9884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yousry TA, Major EO, Ryschkewitsch C, et al. Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(9):924–933. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Miagostovich MP, Ferreira FFM, Guimarães FR, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of gastroenteritis viruses occurring naturally in the stream waters of Manaus, Central Amazônia, Brazil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(2):375–382. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00944-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bofill-Mas S, Calgua B, Rodriguez-Manzano J, et al. Cost-effective Applications of human and animal viruses and microbial source-tracking tools in surface waters and groundwater in Faecal Indicators and pathogens. Proceedings of the Fédération Internationale des Patrouilles de Ski Conference (FIPs '11); 2011; London, UK. Royal Society of Chemistry; [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bidin M, Lojkić I, Bidin Z, Tiljar M, Majnarić D. Identification and phylogenetic diversity of parvovirus circulating in commercial chicken and turkey flocks in Croatia. Avian Diseases. 2011;55(4):693–696. doi: 10.1637/9746-032811-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Palade EA, Kisary J, Benyeda Z, et al. Naturally occurring parvoviral infection in Hungarian broiler flocks. Avian Pathology. 2011;40(2):191–197. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2011.553213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zsak L, Strother KO, Day JM. development of a polymerase chain reaction procedure for detection of chicken and Turkey parvoviruses. Avian Diseases. 2009;53(1):83–88. doi: 10.1637/8464-090308-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Johne R, Enderlein D, Nieper H, Müller H. Novel polyomavirus detected in the feces of a chimpanzee by nested broad-spectrum PCR. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(6):3883–3887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3883-3887.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]