Abstract

Since 1986 medical students at the University Children’s Hospital Essen are trained as peers in a two week intensive course in order to teach basic paediatric examination techniques to younger students. Student peers are employed by the University for one year. Emphasis of the peer teaching program is laid on the mediation of affective and sensomotorical skills e.g. get into contact with parents and children, as well as manual paediatric examination techniques. The aim of this study is to analyse whether student peers are able to impart specific paediatric examination skills as good as an experienced senior paediatric lecturer. 123 students were randomly assigned to a group with either a senior lecturer or a student peer teacher. Following one-hour teaching-sessions in small groups students had to demonstrate the learned skills in a 10 minute modified OSCE. In comparison to a control group consisting of 23 students who never examined a child before, both groups achieved a significantly better result. Medical students taught by student peers almost reached the same examination result as the group taught by paediatric teachers (21,7±4,1 vs. 22,6±3,6 of 36 points, p=0,203). Especially the part of the OSCE where exclusively practical skills where examined revealed no difference between the two groups (7,44±2,15 vs. 7,97±1,87 of a maximum of 16 points, p=0,154). The majority of students (77%) evaluated peer teaching as stimulating and helpful. The results of this quantitative teaching study reveal that peer teaching of selected skills can be a useful addition to classical paediatric teaching classes.

Keywords: Peer teaching, Pediatrics, tutor, basic skills, evaluation

Abstract

An der Universitäts-Kinderklinik Essen werden seit 1986 studentische Tutoren in einem vierzehntägigen Intensivkurs ausgebildet, um im Blockpraktikum Pädiatrie Studierende des 3. und 4. Klinischen Semesters am Krankenbett in basalen pädiatrischen Untersuchungstechniken zu unterrichten („peer-to-peer-teaching“). Die Tutoren werden für ein Jahr als studentische Hilfskräfte in der Klinik eingestellt. Der Schwerpunkt der Tutorenausbildung liegt auf der Vermittlung affektiver und sensomotorischer Fertigkeiten, wie zum Beispiel Kontaktaufnahme zu Eltern und Kindern, sowie auditive und manuelle Fertigkeiten. In dieser prospektiven Studie sollte untersucht werden, ob die Tutoren ausgewählte pädiatrische Untersuchungstechniken ähnlich gut vermitteln können, wie ein erfahrener pädiatrischer Dozent. Einhundertdreiundzwanzig Studierende wurden auf zwei Gruppen verteilt, die entweder einem pädiatrischen Dozenten oder einem studentischen Tutor zugeteilt wurden. Nach einer einstündigen Unterrichtseinheit mussten die erlernten manuellen und verbalen Fertigkeiten im Rahmen einer 10minütigen OSCE-Prüfung demonstriert werden. Gegenüber einer

Kontrollgruppe von 23 Studierenden, die bisher an keinem Unterricht teilgenommen hatte, erzielten beide Untersuchungsgruppen ein signifikant besseres Prüfungsergebnis. Die Studierenden, die von einem Tutor unterrichtet wurden erreichten dabei im direkten Vergleich eine ähnliche Gesamtpunktzahl, wie die Gruppen, die von einem pädiatrischen Dozenten ausgebildet wurden (21,7±4,1 vs. 22,6±3,6 von 38 Punkten, p=0,203). Insbesondere in der Teilaufgabe, in der ausschließlich praktische Fertigkeiten geprüft wurden, zeigte die Gruppe der von einem Dozenten unterrichteten Studierenden keinen punktwerten Vorteil (7,44±2,15 vs. 7,97±1,87 von maximal 16 Punkten, p=0,154). Die Mehrzahl der Studierenden (77%) gab an, dass sie den Unterricht mit den Tutoren als lernförderlich angesehen haben. Die Ergebnisse der quantitativen Untersuchung können belegen, dass der Einsatz von studentischen Tutoren im klinischen Unterricht sinnvoll und lernförderlich ist, wenn diese ausgewählte Lernziele vermitteln sollen.

Introduction

Today’s medical students are tomorrow’s medical teachers [1]. However, faculties‘ medical curricula do no prepare medical students for their later teaching responsibilities which are immediately required in most teaching hospitals. A possible solution could be the implementation of teaching classes where medical students learn to teach [2], [3]. In order to reach that goal medical faculties have to establish new teaching and learning methods [1]. Teaching more practically relevant skills is already required by the new medical approbation order [4], however its implementation is limited by personal resources and, e.g. in paedicatrics, special needs of little children and their parents. Especially teaching in paedicatrics requires a more extensive, patient and committed supervision of the medical students as it may be required for other disciplines [5], [6], [7]. Considering increasing shortage of resources and further responsibilities of lecturers and physicians, new innovative and cheaper solutions are needed [5]. A possible solution might be the implementation of a well-structured, practical workshop in general paediatric examination techniques by student peer teachers (SPT). Data from prospective studies is missing so far showing the effectiveness of such a peer-assisted learning concept. In the University Children’s Hospital of Essen SPT’s are trained for almost twenty years in a 14-days intensive course to teach medical students in the following year in basic paediatric examination techniques [8], [9]. Prof. Olbing has successfully established the peer-teacher training concept in Essen which has been evaluated in 1996 [10]. However, a standard quantitative evaluation of the affective and sensomotorical skills is missing since it was considered to be methodocially too extensive. Instead of that, simply a student questionnaire asking the medical students for their overall satisfaction has been performed. A quantitative analysis was indirectly carried out by reviewing the results of the paper-test in paediatrics [10]. The external evaluation revealed that SPT’s are considered stimulating and helpful. There are only few studies demonstrating that SPT’s are equally capable of mediating selected paediatric skills when compared to senior paediatric lecturers (SL, [11]). Therefore, a quantitative analysis of peer teaching in paediatrics is urgently required, not only because teaching the peers and its’ organization is time consuming and expensive. However, this expense is justified if such a study could demonstrate that SPT’s are equally qualified to mediate selected basic paediatric skills. In this respect SPT’s should not replace teaching responsibilities of SL’s but should make teaching easier for them because of their intermediate position in a hospital’s hierarchy.

The aim of this prospective study is the clarification of two questions:

Is a SPT after a 14-days intensive course able to equally mediate selected paediatric skills like a SL?

Do medical students consider the use of SPT stimulating and helpful?

The last question should be answered by using a questionnaire at the end of the paediatric teaching course.

Methods

Study design

This study is a randomized, two-armed comparison study with 123 medical students of the same semester performed in a pre-/post-design. Medical students (52 male, 71 female) were randomly assigned to arm A or B with 60 and 63 students per group. In addition, 23 students (9 male, 14 female) of the same semester were not randomized and served as control group. A pre-test was performed solely in this group to check for preexisting experiences in paediatric examinations. The unequal group sizes resulted from organizational needs and were accepted. A student peer teacher (SPT) was assigned to 63 students (group A) and a senior lecturer (SL) to 60 students (group B). In a one hour paediatric class students had to examine a newborn. No more than two students were instructed in either SPT or SL groups and no further examintations of newborns were performed. After 1-4 days students had to demonstrate the learned skills in a modified 10-minute OSCE.

Since standard examination sheets were not available a non-validated checklist was designed in our hospital by a paediatric expert committee. Same criteria for the control group and the examination groups were used. The demonstration was performed in front of an independent examiner who was not informed about the study goal. To avoid a bias, video recording of the OSCE was perfomed in 30 cases (15 students from each group) and evaluated by an external observer. Students gave their written consent that they were willing to participate in the study and video recording.

Peer teaching

Peer teaching took place from February 9th to February 20th at the University Children’s Hospital of Essen. At that time all tutors finished the 4th or 5th medical semester and all applied for a position in this program in summer 2008. Eleven students were selected. An elective period in paediatrics over one month and the successful participation of the paediatric course was assumed. Peer teaching followed a fixed time table and lasted 80 hours. During the curriculum examination of 10 children, demonstration of the examination results and short lectures on specific diseases as well as special teaching lessons of examination techniques were performed. A script was handed out to each tutor. Lectures were performed by seven senior physicians and one junior physician assisted the tutors with the examinations. Tutors performed the same OSCE at the end of the curriculum which was later on used in the study. All paediatric lecturers were experienced and did not perform the OSCE.

Selection of students

Out of summer semester 2009 and winter semester 2009/2010, 60 and 63 medical students respectively have been randomly assigned to a study group. At that time all students participated in the 14-day paediactric class. All participants had the chance to listen to the paediatric lectures in the two semesters before and all passed the final written exam. The study group size of 60 students each arm resulted from a statistical calculation. A pre-test was performed in the control group only on the first day of the paediatric class in order to compare the student’s knowledge before and following the intervention. We assumed that the preexisting knowledge was different among the groups because of prior elective periods in paediatrics. The control group underwent the same teaching classes as the study groups; however, the OSCE was not repeated again at the end of the intervention in this group. Unequal group sizes resulted from organizing reasons. The students have been informed about the study goals prior to the intervention. Nobody underwent the OSCE before.

This study has been approved by the ethical committee of the University of Duisburg Essen (No.09-3967). All participants gave their written consent for the OSCE after being informed that the results of the examination do not count for the final exam results. A written consent for video documentation was given separately by the participants.

„Standard mothers“

It seemed to be important that students had to perform the OSCE under conditions close to reality. Therefore, the examination took place in a standard examination room of our clinic supported by two nurses. The nurses have been trained to act as a mother with mirgration background.

Rater

OSCE-raters were specialized paediatricians as well as junior paediatricians. The raters did not take part in the student’s teaching classes before and they did not know whether the student has been taught by a SPT or SL. Due to the heterogeneity among the groups and to avoid a subjectivity bias (rater knew the student before and gave him/her a better score) a video documentation of the examination was performed in 30 cases. Those videos were observed by an external paediatrician later on who was not involved in the medical education of the University and did not know the students.

OSCE

A regular OSCE was not suitable to answer the study question since a parcours consisting of different exercises was not possible to perform for 146 single examinations. Therefore we designed a single parcours and tested several skills in one examination (Attachment 1). In five exercises, several skills were tested:

Exercise 1: address the parents; begin the examination = communication skills

Exercise 2: measurement of head circumference/demonstrate palpation of the pulses = practical skills

Exercise 3: demonstrate neurological examination = practical skills

Exercise 4a: summarize results as medical report = communication skills, abstraction

Exercise 4b: prepare checklist = communication skills, abstraction

Considering the multiplicity of items, an examination time of 10 minutes was allowed for the modified OSCE. The number of points that could be reached per item was not equally distributed. Out of 38 total points, a maximum of 6 points could be reached in exercise 2 and 16 points in exercise 3 (neurological examination of a newborn). The OSCE took place on the last day of the week of the four clinical examinations. Therefore, the distance between the SPT and SL mediated intervention and the examination was 4 days maximum (Monday – Friday) or 1 day minimum (Thursday - Friday). Same distances were not possible because of the multiplicity of exams. The exercises and the checklist could not be validated prior to the study in a larger cohort. However, parts of this OSCE have been used for the first paediatric OSCE in summer 2009 and a sharp separation could be achieved in 115 students.

Calculation of group size and statistical analysis

To calculate the number of subjects needed one had to assume that a single question needs to be answered in this study: Is a SPT after a 14-days intensive course able to equally mediate selected paediatric skills like a SL (yes/no)? The assumed α-mistake is <0.05 (5%). To reach a sufficient statistical power (> 0.80, power d≥0.5) a group size of at least 60 students per arm has to be selected. This has been considered for the calculations. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and the „range“ has also be given for all results. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided t-test for independent groups using the statistical program GraphPad Prism version 4.0 (San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Acceptance of examination

Although participation in this study did not account for the final exams and students had to spend extra time we received a positive feedback from most of the students and a less enthusiastic participation was rarely observed. Most students found the study useful and only one student declined participation. Three students did not agree into a video documentation during the OSCE. All 146 examinations could be finished. Examination of the tutors took place in February 2009 and their results are also given as comparison.

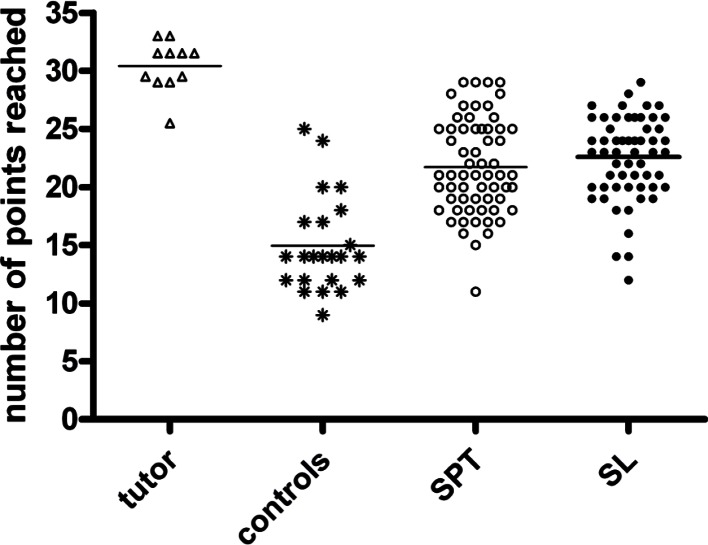

Overall results of the OSCE

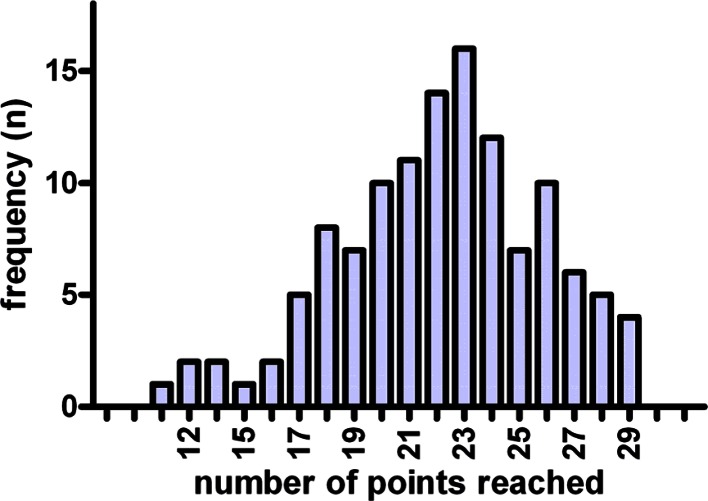

A maximum of 38 points could be reached in the OSCE. The 11 tutors reached a high average result of 30.4±22 points (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). The control group reached 14.9±4.1 points, SPT 21.7±4.1 points and the SL group reached 22.6±3.6 points (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). Tutors performed significantly better when compared to all other groups (p<0.001); SPT and SL achieved a significantly better result when compared to controls (p<0.001), however, no significant difference was observed between SPT and SL (p=0.203, see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). The distribution of points reached by all 123 students in the OSCE is given in Figure 2 (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Overall results of the OSCE for all groups. A maximum of 38 points could be reached. Students taught by a SPT achieved a similar amount of points when compared to the group taught by a SL.

Figure 2. Frequency of the OSCE-results of all students (n=123) in the randomized study.

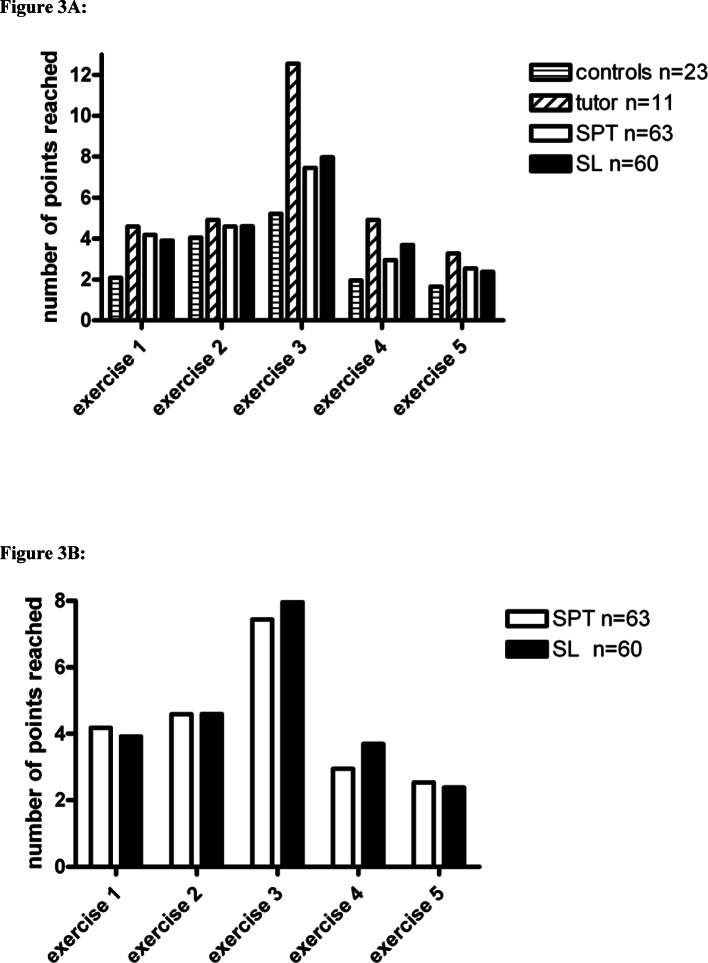

Results of single exercises

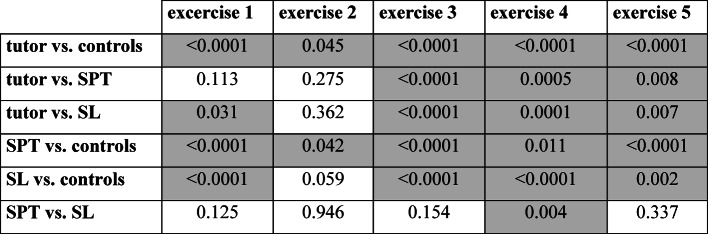

The modified OSCE consisted of 5 different exercises examining different skills. The results of all exercises are presented in Figure 3 (Fig. 3). Results reached by students in the SPT and SL teacher are also given separately for a better understanding (see Figure 4 (Fig. 4)). It is remarkable that many significant differences were observed among the groups (see Figure 4 (Fig. 4) and Table 1 (Tab. 1)), e.g. students in the SPT and SL groups always reached significantly better results in all exercises when compared to controls (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). However, only few differences became obvious when SPT and SL groups were compared directly (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). Especially exercise 3 where only practical skills were tested no differences were observed among SPT and SL (7.44±2.15 vs. 7.97±1.87, p=0.154). In this important exercise 12 of 16 points maximum were reached in both groups with a similar range. Only in exercise 4 where students were asked to summarize their examination results into a medical report, SL groups performed better than SPT groups (p=0.004). However, this difference seems to be significant but not relevant when considering the total amount of points reached in this exercise (3.7±0.94 vs. 2.95±1.76 out of 6 points maximum). Tutors performed significantly better in all single exercises when compared to controls, SPT and SL groups (see Figure 3 (Fig. 3)). This demonstrates that the 11 tutors after taking part in a 14-days intensive course were capable to perform as teachers.

Figure 3. Means of results reached in all different exercises of the OSCE.

Results of controls, tutors, SPT- and SL-groups are presented (Fig. 3). In addition, SPT- and SL-groups are separately displayed (Fig. 4). In this randomized trial significant differences were only observed in exercise 4 (medical report; SL vs. SPT p=0.04). More statistical analyses are given in table 1.

Figure 4. Typical examination situation as shown in the video.

In 30 cases the OSCE was filmed and evaluated by an external examiner.

Table 1. Statistical differences between groups in the OSCE.

P-values for independent groups were analyzed using a two-sided t-test. Significant differences are highlighted in gray fields (p<0.05).

Results of the video analysis

In 30 OSCEs‘ video recording was performed. Those 10 minute video films were evaluated by an external paediatrician using the same checklist. A maximum of 1 point difference was observed in exercise 4 and 5 among two students and also a maximum of 1 point difference in exercise 3 within 6 students. We used the video documentation to exclude that scoring depended on sympathy for a single student.

Questioning of the medical students

In summer 2009 we asked 112 students after they have finished their paediatric training whether they found teaching classes performed by tutors helpful and stimulating („Did you find the use of student peer teachers helpful? yes - no“). In 86 cases (77%) students answered that they consider the work with a student peer teacher helpful, howerver, 23% did not see an advantage using this form of medical education. Few interviews revealed that some students do not believe in general that a student teacher should be involved in medical education classes.

Discussion

In this quantitative teaching/learning study the peer-to-peer teaching concept of the University Children’s Hospital of Essen was evaluated using a paediatric neurological standard examination situation. Although some paediatric studies addressing peer teaching in paediatrics were performed over the past years only few publications evaluated the role of student peer teachers in clinical classes [8], [9], [10]. Most studies referred to problem-based learning [12], virtual patient cases [13], [14] or taking a medical history in paediatrics [15] but only few data referring to paediatric peer-teaching using practical skills exist [16]. The aim of this study was to provide this data using a time and personal intensive, but simple design. We have demonstrated in this randomized study using an OSCE of a newborn examination that mediation of selected skills can be equally achieved by SPT and SL. Therefore it is feasible to use student peer teachers for clinical paediatric courses if they are well educated and mediation is limited to selected basic skills. Furthermore, the majority of students consider the tutorial support as helpful. In this respect we clearly answered to our primary research question.

To our knowledge this is the first study investigating in parallel the mediation of basic paediatric skills by SPT and SL. This is one major advantage of this study. The results confirm our recent teaching strategy and are highly motivating for all participants to carry on and improve the concept. There are also advantages for the paediatric departments since motivated tutors are the pool for recruiting future paediatricians. A further strength is the control of OSCE results by a blinded external observer since a subjectivity bias could be avoided and similar results were reached. The use of ‘standardized mothers’ with migration background was a further special feature of this study. This is a regional peculiarity and important to know. Adequate communication with parents is undoubtedly one of the major challenges in paediatrics. Upon study conception we could not look back on previous experiences although the learning benefit of standardized patients is well documented in the literature [12], [13]. So far, only few studies described the effectiveness of ‘standardized parents’ [14]. Therefore, there is only empiric experience in the communication with parents with migration background and we tried to train our nurses realistic using our own experiences.

However, caution should be used when interpreting the results. The study goal was not to define the better teacher. Such a question could not be answered using this simple design. It is also not permissible to relieve senior lecturers from their tasks and replace them by cheaper peer-teachers. Clearly the peer-to-peer-teaching concept in a paediatric course could be confirmed quantitatively in a prospective, randomized study. The student tutor is able to mediate selected clinical teaching responsibilities and is therefore a useful addition based on its intermediate position in a hospitals’ hierarchy. A tutor does not replace a lecturer because he does not secure the interpretation in an entire context. Such study limitations have to be considered when peer-teaching programs are established. Especially the quality of mediating complex skills has to be guaranteed by a senior lecturer and not a student peer [17]. You can’t assume that every student peer is also a good teacher. However, the good OSCE results of our 11 tutors demonstrated that the necessary tools and the specific background were given.

The success of peer-supported classes in medical schools can subjectively be demonstrated in several studies [11], [18], [19], [20], [21]. But only few studies, mostly presented as meeting abstracts, investigated quantitatively the effectiveness of peer-teacher mediated skills in direct comparison with postgraduated lectureres, e.g. using an OSCE [17], [18]. At least there are no major paediatric studies known beside meeting reports. In general, several educational goals can be reached by the establishment of tutor-programs [20]:

Today’s medical students take over prime teaching positions in their hospitals later on.

By taking part in tutorial programs future physicians are trained in communicative skills that might be extremely useful in their future careers.

A better understanding of teaching and learning might also stimulate a students‘learning behavior.

At short notice implementation of classes like ‚learn how to teach for students‘might be more laborious for medical faculties. On a long-term basis the improvement of the existing teach/learn-culture might be useful for a University’s reputation [20]. There are two explanations from teaching psychologists why tutor-based education is successful. Allen’s roll theory [22] assumes that teacher and scholar accept different stereotypic rolls with different expectations, responsibilities and hierarchic positions, which are separated from each other by psychological and physical barriers. In this model the congruent roll of the tutor with the students strengthens one motivation to learn („self-directed learning“) while the fear to fail seems to be the learning trigger when educated by an experienced teacher. A further theory by Schmidt [23] postulates the existence of a cognitive incongruence between faculty members and students and congruence between student peer teachers and students. Therefore it is easier for SPT‘s to include preexisting knowledge or existing lacks, especially the usage of language and thinking in one’s teaching classes [23]. This might explain why the acceptance of a student tutor is higher than assumed [23], [24].

The methodological study limitations are obvious. Most of them were known when the study was designed but were accepted for practicability reasons. One problem is that the modified OSCE consists of several items but only a single rater. The design of a complete OSCE parcours with various exercises and different raters would be more adequate but too time-and observer-consuming and therefore not practicable [25]. It was our goal to design only one OSCE parcours and to test various clinically relevant skills in a single examination. Furthermore, the OSCE was meant to take part soon after the intervention since only a single hour was used for it. This requires an examination every week and not one major OSCE parcours at the end of each semester. The use of an external observer could at least demonstrate that the use of only one rater did not negatively influence the results.

The exam did reveal poorer results than normally expected in an OSCE, at least when considering the test-centered level for passing an exam according to Ebel or Angoff [26], [27]. Only 60% of all participants would have passed with an arbitrary limit of 60%. Therefore one has to ask whether the chosen form of examination is a valid tool to discriminate between competent and incompetent students or whether the level was too high for an OSCE in general. Again, the discrimination level would have been better in a parcours consisting of 5-10 items. It is also obvious that the difficulty of the 5 items varied, e.g. exercise 1, 2 and 5 were equally handled by all participants whereas solution of exercise 3 reveals a much greater heterogeneity, leaving exercise 3 with the highest difficulty and separation power. To further reveal the validity of our exam we also included the tutors’ and controls’ results in the analysis. When looking at the tutors’ results one can see that all exercises where solvable after some training since this group reached 30.4?2.2 of 38 points. The control group reached significantly fewer points when compared to all other groups. Therefore, one can conclude that the chosen form of exam was adequate to answer the study question since all participants reached better results following the intervention when compared to controls showing that they all profited from teaching classes. However, the chosen exam is not an adequate measure to discriminate between competent and incompetent students, but that was out of a question.

A majority of 77% found tutor’s teaching classes stimulating and helpful. In order to avoid an evaluation tiredness we deliberately asked only a single question which had to be answered by ‘yes’ or ‘no’. This does not reveal the individuals‘ intrinsic motivation. An entire questionaire would have been necessary to assess the quality of tutors‘ teaching classes in comparison to SL. Therefore, a possible Hawthorne-effect („but some students had a real lecturer…“) that might have changed one’s behavior in the exam cannot entirely be excluded by our results [28]. However, the quality of medical training has previously been evaluated in detail and was not the focus of this study [10].

Conclusion

The results of this quantitative teaching study reveal that student peer teaching can be a useful addition to classical paediatric teaching classes. Student peer teachers are as effective as senior lectures when mediating selective skills. A two week intensive training seems to be adequate to prepare the peers for their future tasks.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by a generous grant of the dean of studies of the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

This work is dedicated to Prof. Hermann Olbing [†].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Morrison EH, Hafler JP. Yesterday a learner,today a teacher too: Residents as teachers in 2000. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1 Pt 3):238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspegren K. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine – a review with quality grading of articles. Med Teach. 1999;21(6):563–570. doi: 10.1080/01421599978979. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421599978979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students' perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329(469):770–773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Approbationsordnung für Ärzte, Beschluss des Bundesrates vom 26.4.2002. Bonn: Bundesanzeiger Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallat ME, Glover J American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics. Professionalism in Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1123–e1133. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2230. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pölzelbauer K. Arzt – Kinde – Eltern: Kommunikation in der Pädiatrrie; Schwerpunkt: Gesprächsführung in Krisensituationen, siehe Informationstexte zu den Lehrveranstaltungen der Universität Heidelberg. Heidelberg: Universität Heidelberg; 2005. Available from: http://www.klinikum.uni-heidelberg.de/fileadmin/zpm/medpsych/Kurstexte_WS_06-07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crossley J, Davies H. Doctor's consultations with children and their parents: a model of competencies, outcomes and confounding influences. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):757–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02231.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.lbing H, Gottschalk B, Groes A, Rascher W. Akzeptanz von Tutoren im Praktikum Kinderheilkunde. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1992;140(2):128–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bannister SL, Hilliard RI, Regehr G, Lingard L. Technichal skills in paediatrics: a qualitative study of acquisition, attitudes and assumptions in the neonatal intensive care unit. Med Educ. 2003;37(12):1082–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2003.01711.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2003.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steiger J, Rossi E. Evaluation des Pädiatriestudentenpraktikums in Essen. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1997;145:519–525. doi: 10.1007/s001120050153. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001120050153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasquinelli LM, Greenberg LW. A review of medical school programs that train medical students as teachers (MED-SATS) Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(1):73–81. doi: 10.1080/10401330701798337. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10401330701798337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wendelberger KJ, Simpson DE, Biernat KA. Problem-based learning in a third-year pediatric clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 1996;8:28–32. doi: 10.1080/10401339609539760. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10401339609539760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubal RC, Deterding RR, Frank GA, Schwetzke HF, Kizakevich PN. Lessons learned in modelling virtual pediatric patients. In: Westwood JD, editor. Medicine Meets Virtual Reality 11: NextMed – Health Horizon. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2003. pp. 127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huwendiek S, Reichert F, Bosse HM, de Leng BA, van der Vleuten CP, Haag M, Hoffmann GF, Tönshoff B. Design principles for virtual patients: a focus group study among students. Med Educ. 2009;43(6):580–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03369.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrows HD. An overview of the uses of standardized patients for teaching and evaluating clinical skills. Acad Med. 1993;68(6):443–451. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199306000-00002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lane JL, Ziv A, Boulet JR. A Pediatric Clinical Skills Assessment Using Children as Standardized Patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):637–644. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frobenius W, Ganslandt T, Jünger J, Beckmann MW, Cupisti S. Effekte von Peer Teaching in einem geburtshilflich-gynäkologischen Praktikum. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:848–855. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185748. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1185748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weyrich P, Schrauth M, Nikendei C, Kraus B, Häring HU, Riessen R. Implementierung eines studentischen Tutorsystems im Skills Lab für Innere Medizin – Eine Pilostudie. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2007;24(1):Doc15. Available from: http://www.egms.de/static/de/journals/zma/2007-24/zma000309.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadoodi A, Crosby JR. Twelve Tips for peer-assisted learning: a classic concept revisited. Med Teach. 2002;24(3):241–244. doi: 10.1080/01421590220134060. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590220134060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558–565. doi: 10.1080/01421590701477449. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701477449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cate OT, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591–599. doi: 10.1080/01421590701606799. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701606799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen N, Mondschain B. The medical role in the adolescent crisis intervention centrer. Adolescene. 1976;11(42):157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt HG, Moust JH. What makes a tutor effective? A structural-equations modeling approach to learning in problem-based curricula. Acad Med. 1995;70(8):708–714. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199508000-00015. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199508000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baroffio A, Nendaz MR, Perrier A, Layat C, Vermeulen B, Vu NV. Effect of teaching context and tutor workshop on tutorial skills. Med Teach. 2006;28(4):e112–e119. doi: 10.1080/01421590600726961. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590600726961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosse HM, Wittekindt B, Höffe J. Prüfen in der Kinder- und Jugendmedizin. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2008;156:467–472. doi: 10.1007/s00112-008-1728-5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00112-008-1728-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebel RL. Essentials of educational measurement. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angoff WH. Scales, norms, and equivalent scores. In: Thorndike RL, editor. Educational measurement. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Council of Education; 1971. pp. 508–600. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gnädiger M, Marthy F. Beim Placebo wirkt mehr als die Pille allein. Gedanken zur Studienmethodik anlässlich von zwei Schlafuntersuchungen. Schweiz Med Forum. 2007;7:318–324. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klamen DL, Yudkowsky R. Using standardized patients for formative feedback in an introduction to psychotherapy course. Acad Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):168–172. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.26.3.168. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.26.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Towle A, Hoffmann J. An advanced communication skills course for fourth-year, post clerkship students. Acad Med. 2002;77(11):1165–1166. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200211000-00033. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200211000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosse HM, Nikendei C, Hoffmann K, Kraus B, Huwendiek S, Hoffmann GF, Jünger J, Schultz JH. Communication training using "standardized parents" for paediatricians – structured competence-based training within the scope of continuing medical education. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 2007;101(10):661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.zgesun.2007.11.002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.zgesun.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.