Abstract

Study Objectives:

Although difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS) is the most common nighttime insomnia symptom among US adults, many FDA-approved hypnotics have indications only for sleep onset, stipulating bedtime administration to offset residual sedation. Given the well-known self-medication tendencies of insomniacs, concern arises that maintenance insomniacs might be prone to self-administer their prescribed hypnotics middle-of-the-night (MOTN) after nocturnal awakenings, despite little efficacy-safety data supporting such use. However, no US data characterize the actual population prevalence or correlates of MOTN hypnotic use.

Methods:

Telephone interviews assessed patterns of prescription hypnotic use in a national sample of 1,927 commercial health plan members (ages 18-64) receiving prescription hypnotics within 12 months of study. The Brief Insomnia Questionnaire assessed insomnia symptoms.

Results:

20.2% of respondents reported MOTN hypnotic use, including 9.0% who sometimes used twice-per-night (once at bedtime plus once MOTN) and another 11.2% who sometimes used MOTN, but never twice-per-night. The remaining 79.8% used exclusively at bedtime. Among exclusive MOTN users, only 14.0% used MOTN on the advice of their physician (52.6% of those seen by sleep medicine specialists and 42.6% by psychiatrists vs. 5.2% to 13.6% seen by other physicians). MOTN use predictors included DMS being the most bothersome sleep problem, long duration of hypnotic use, and low frequency of DMS.

Conclusions:

One-fifth of patients with prescription hypnotics used MOTN, only a minority on advice from their physicians. Since significant next-day cognitive and psychomotor impairment is documented with off-label MOTN hypnotic use, prescribing physicians should question patients about unsupervised MOTN dosing.

Citation:

Roth T; Berglund P; Shahly V; Shillington AC; Stephenson JJ; Kessler RC. Middle-of-the-night hypnotic use in a large national health plan. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9(7):661-668.

Keywords: Insomnia, sleep maintenance, hypnotics, middle-of-the-night, dosing, medication adherence, prevalence

Insomnia is the most common nighttime sleep problem, and sleep maintenance insomnia the most common insomnia symptom both in the general population1 and among adults with clinical insomnia.2 An estimated one-fourth of all non-institutionalized US civilians and two-thirds of US insomniacs report frequent sleep maintenance problems involving nocturnal awakenings and/or prolonged wake time after nocturnal awakenings.2 Although insomnia symptoms are highly variable from night to night and frequently co-occur, DMS presents alone in roughly 20% of transiently or moderately symptomatic adults and 17% of insomniacs.2 DMS persists in more than 90% of population-based cases for at least 6 months3 and upwards of 70% for at least one year.4 Sleep maintenance insomnia is associated with a variety of impairments, including: daytime sleepiness3; disruptions in cognition, motor coordination, and mood3; decrements in perceived health2; and increased health-care utilization.5 Sleep maintenance insomnia accounts for more daytime sleepiness6 and poor perceived health2 than any other nighttime insomnia symptom.

Despite the high prevalence of sleep maintenance insomnia, the indications of many widely used hypnotics currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specify efficacy only for sleep onset.7,8 Furthermore, among those hypnotics that are approved for nocturnal awakenings and/or prolonged wake time after nocturnal awakenings, all but one stipulate bedtime administration with middle-of-the-night use being explicitly disapproved to minimize risk of residual sedation. In other words, such bedtime hypnotics are designed to be preventative treatments for possible nocturnal awakenings rather than active treatments administered after nocturnal awakenings occur. The single hypnotic accepted by the FDA for as-needed MOTN use after nocturnal awakenings to date was approved only very recently (http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm281013.htm. Published November 23, 2011. Accessed November 23, 2011).

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Although difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS) is the most common nighttime insomnia symptom among US adults, many FDA-approved hypnotics have indications only for sleep onset and specify bedtime administration to offset next-day sedation. Given the well-known self-medication tendencies of insomniacs and adverse cognitive and psychomotor impacts of hypnotic-related residual sedation, it is important to assess possible off-label MOTN use among maintenance insomniacs in the community.

Study Impact: The current study offers a preliminary view of real-world MOTN hypnotic use in a national sample of insured Americans. Information is also provided on the distribution of insomnia symptoms of once-a-night MOTN users and recommendations for MOTN use by prescribing physicians.

Given that 40% to 80% of insomniacs with prominent sleep maintenance problems do not experience symptoms every night,9 and many are only symptomatic 3-4 nights a week,3 one potentially important difference between nightly bedtime hypnotic use to prevent nocturnal awakening and as-needed MOTN use only after nocturnal awakenings occur is a dramatic reduction in the frequency of hypnotic use with MOTN dosing. Although it is difficult to know if this reduced frequency of hypnotic use would have beneficial health effects, as documenting adverse effects of prolonged hypnotic use is problematic given the well-known physical and psychological vulnerabilities of long-term hypnotic users. It is noteworthy, though, within the context of that limitation that prolonged hypnotic use has been linked with multiple subsequent adverse health outcomes.10

Hypnotics approved for bedtime use to prevent nocturnal awakenings have demonstrated inconsistent effects on sleep maintenance parameters during controlled treatment trials.8 In light of these inconsistent efficacy profiles, experimental studies have begun exploring efficacy-safety of MOTN dosing of FDA-approved (for bedtime use) hypnotics9,11–13 and investigational agents.14,15 Although these studies have found MOTN dosing of these medications associated with improvements in sleep maintenance, trials involving off-label use of approved hypnotics have also found next-day compromises in psycho-motor and cognitive functioning,13,16–18 especially at higher dosages. Concerns have been raised that the tight controls in these studies may underestimate real-life adverse effects of MOTN use owing to patient non-compliance regarding hypnotic dosages and timing of doses.17,18 For instance, studies of blood levels among drivers stopped for driving under the influence (DUI) in the United States,19 Norway,20 and Sweden21 have found higher-than-expected blood levels of various hypnotic drugs, suggesting that hypnotic misuse involving escalated dosages and/ or improper timing of doses may be associated with impaired driving.22 This is consistent with other evidence that high proportions of insomniacs self-medicate.23

Since many of the most widely used hypnotics approved by the FDA have indications that specify efficacy only for sleep onset symptoms, concern arises that maintenance insomniacs might be prone to self-administer their prescribed hypnotics after nocturnal awakenings despite little efficacy-safety data supporting off-label MOTN use. Given possible adverse short-term impacts of off-label MOTN dosing on cognitive and psychomotor functioning, possible long-term impacts of prolonged hypnotic use on health, and the very high prevalence of DMS, it is important to establish the extent of unsupervised MOTN hypnotic use in the population. However, we are aware of no community-based epidemiological data regarding the actual magnitude or correlates of MOTN dosing. We conducted a survey to provide basic data of this sort in a sample of insured employees of a large national health plan receiving hypnotic prescriptions during the 12 months before study. As restrictive conditions on recruitment imposed by the Health Plan resulted in a low survey response rate, caution must be used interpreting results. Nonetheless, the findings are useful given absence of other data on this issue.

METHODS

The Sample

The sample consisted of adult (ages 18-64 years) members of a large (over 34 million members) national US commercial health plan who received prescriptions for one or more FDA-approved hypnotics at some time in the 12 months before the survey. The sample was restricted to fully insured members enrolled in the Health Plan for at least 12 months in order to allow claims data to be used in substantive analyses. Sample eligibility was also limited to members who provided the Plan with a telephone number, spoke English, and had no impairment that precluded their ability to be interviewed by telephone. The sample was selected with stratification to match the health plan distribution on the cross-classification of age (18-34, 35-49, 50-64) and sex. In an effort to limit sample burden, attempts to contact respondent households were limited by the Health Plan to 2 contacts, except for a 25% subsample of households, in which up to 9 calls were permitted in order to obtain at least some information about hard-to-reach respondents. The data were weighted to adjust for this under-sampling of hard-to-reach respondents.

Recruitment and Consent

Survey recruitment began with an advance letter sent to a probability sample of Plan members meeting eligibility requirements explaining that the survey was designed “to better understand how sleep problems affect the daily lives of people,” that respondents were randomly selected, that responses were confidential, that participation was voluntary and would not affect health care benefits, and that a $20 incentive was offered for participation among eligible respondents. A toll-free number was included for respondents who wanted to ask questions or opt out. Following initial phone contact, verbal informed consent was obtained before beginning interviews. The Human Subjects Committee of the New England IRB (www.neirb.com) approved these recruitment, consent, and field procedures.

Measures

The survey consisted of two parts. All respondents were administered Part I, which asked them to specify when during the course of the evening or night they used their sleep medication(s) in the past 12 months. Part II of the survey was then administered only to (i) all Part I respondents who acknowledged using FDA-approved hypnotics after nighttime waking in order to resume sleep, but who never used hypnotics twice in one night (i.e., both at bedtime to get to sleep and also after waking at night to resume sleep), whom we refer to throughout this paper as once-per-night MOTN users, and (ii) a random 20% subsample of Part I respondents who reported using sleep medications exclusively at bedtime, whom we refer to as exclusive bed-time users. We excluded from Part II all those who ever used both at bedtime to get to sleep and also after waking at night to resume sleep, whom we refer to as twice-per-night MOTN users. The Part II data were weighted so that the exclusive bedtime users received a weight of 5 (i.e., the reciprocal of 20%) to adjust for their under-sampling into Part II, making the weighted Part II sample representative of all once-per-night MOTN users or exclusive bedtime users.

In addition to assessing patterns of hypnotic use, the Part II survey examined insomnia symptoms using the Brief Insomnia Questionnaire (BIQ),24 a self-report measure of insomnia symptoms without diagnostic hierarchy rules or organic exclusion rules that has been validated for use in telephone surveys. As respondents were by definition treated insomniacs, BIQ questions asked how frequently they would have each of 4 nighttime sleep problems if they were unable to use sleep medications: difficulty initiating sleep (DIS), difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS), early morning awakening (EMA), and non-restorative sleep (NRS). This was done by prefacing the questions with the following instruction: Imagine that you were unable to take your sleep medicine at all. We then asked respondents to estimate about how many nights out of 7 in a typical week they would have problems falling asleep, have problems remaining asleep throughout the night, wake up before you wanted to, and wake up still feeling tired or unrested if they were unable to take sleep medicine. Follow-up questions to positive responses then probed for information about typical duration (e.g., how many minutes or hours it would typically take them to fall asleep). Respondents reporting more than one of these sleep problems were asked which one was most bothersome. Respondents were also asked about the duration and frequency of their hypnotic use. MOTN users were additionally asked about frequency of this use. Finally, all Part II respondents were administered a battery of standard sociodemographic questions. The complete text of the interview is posted at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/AIS_Study.php.

Analysis Methods

Given the low response rate, analysis began by comparing respondents to non-respondents on key characteristics available from health plan records. This was done with simple cross-tabulations. A post-stratification weight using the regression-based propensity score method25 was then used to correct for significant differences between respondents and non-respondents on these variables prior to carrying out substantive analyses. Cross-tabulations with these weighted data were then used to estimate the prevalence of MOTN use in the Part I sample (all of whom, as noted above, received prescriptions for ≥ 1 FDA-approved hypnotic(s) in the past 12 months), while means were calculated to estimate the proportion of all instances of hypnotic use that occurred at bedtime versus MOTN. Cross-tabulations and multiple logistic regression analysis were then used in the weighted Part II sample (which, as noted above, included once-per-night MOTN users and exclusive bedtime users, but excluded twice-per-night MOTN users) to study the correlates of once-per-night MOTN use versus exclusive bedtime use. Logistic regression coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated for ease of interpretation and are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals. As survey data are weighted, the design-based Taylor series linearization method26 implemented in the SAS 9.2 software system27 was used to estimate standard errors of coefficients and to calculate F tests and Wald χ2 tests. Standard errors of prevalence estimates are reported in parentheses in the text to the right of the prevalence estimates. Statistical significance was consistently evaluated using 0.05-level two-sided tests.

RESULTS

The Survey Cooperation Rate

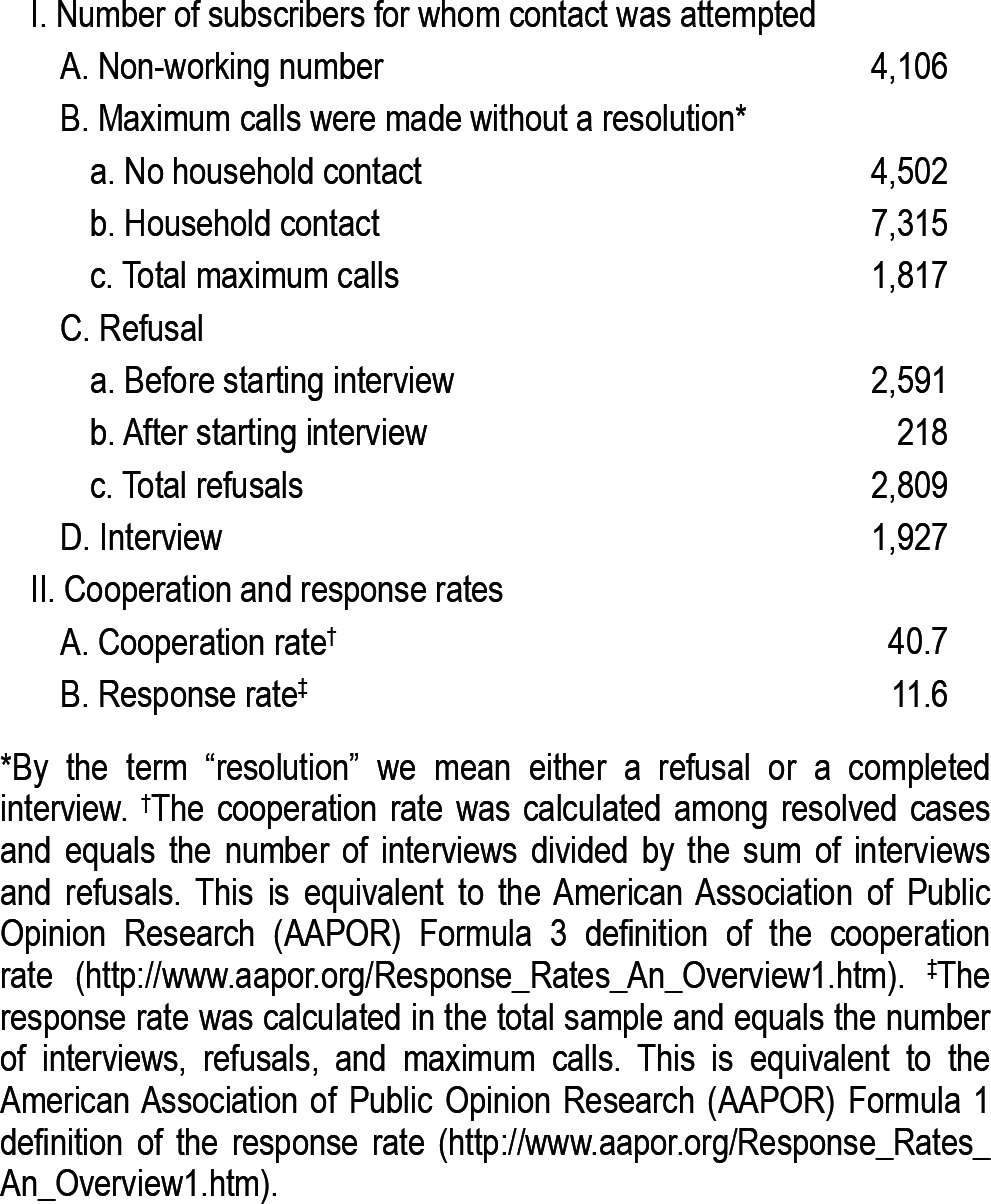

The survey cooperation rate among resolved cases (i.e., the rate of survey completion among target respondents with known working telephone numbers who were reached and whose status was resolved as either completers or refusers, excluding respondents who were never reached and those who were reached but remained unresolved when data collection ended) was 40.7% (Table 1). This is comparable to the cooperation rates found in major government telephone surveys. For example, the 2009 CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey28 had a cooperation rate, calculated in the same way as here, of 43.1% (ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Data/Brfss/2009_Summary_Data_Quality_Report.pdf; Accessed September 28, 2011).

Table 1.

The distribution of survey response dispositions

It should be noted, though, that the Health Plan imposed rather restrictive conditions on the recruitment process, as any potential respondent household that was reached twice without obtaining a resolution (an interview, a refusal, or a confirmation of ineligibility) could not be contacted a third time. Unresolved cases included those in which the target respondent was not at home or said it was an inconvenient time to be interviewed. Since Plan restrictions on number of phone contacts prevented follow-up with many unresolved cases, the survey response rate (i.e., the proportion of all households we attempted to contact that yielded an interview exclusive of those known not to be eligible) was only 11.6%. This is much lower than response rates obtained in surveys in which no such limitations on number of contact attempts are imposed.

Comparisons between Respondents and Non-Respondents

The 1,927 respondents who completed the Part I survey (including both the subsample administered the Part II survey and the subsample administered only the Part I survey) were compared to non-respondents on key characteristics available from Health Plan records, including sociodemographics (age, sex), geographic information obtained by matching the zip code of household residence with Census data (region of the country, urbanicity, and median household income in the Block Group of residence), and global illness severity in the 12 months before interview as assessed by the Deyo-Charlson score.29 Respondents were somewhat older than non-respondents, somewhat more likely to be female and to live either in the Midwest or South, and less likely to live in the West or in major metropolitan areas. Respondents also lived in zip code areas with lower incomes than non-respondents. (Detailed results are available on request.) Finally, respondents had higher global illness severity than non-respondents. As noted in the section on analysis methods, a weight was imposed on the respondent data to adjust for these differences between respondents and non-respondents.

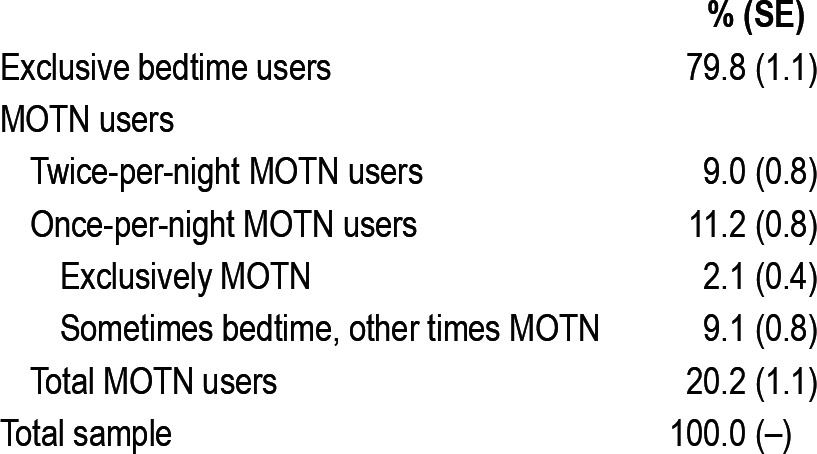

Prevalence of MOTN Hypnotic Use

While 79.8% (1.1) of Part I respondents, representing all hypnotic users, reported that they were exclusive bedtime users, the other 20.2% (1.1) reported being MOTN users (Table 2). The latter include 11.2% (0.8) once-per-night MOTN users (2.1% [0.4] exclusively MOTN and 9.1% [0.8] sometimes at bedtime and other times MOTN) and 9.0% (0.8) twice-per-night MOTN users. As noted above in the section on analysis methods, the parenthetical entries to the right of the prevalence estimates are the standard errors of these estimates.

Table 2.

Distribution of exclusive bedtime and MOTN hypnotic use in the Part I sample (n = 1,927)

The health plan from which we selected the survey sample reported that 2.6% of members in the 18- to 64-year age range had a prescription sleep medication at some time in the 12 months before the survey. If we assume provisionally that this rate applies to the total US population in the age range of the sample and that the sample estimate that 20.2% of prescription hypnotic users use MOTN applies equally to other hypnotic users in the US population, then the total of such MOTN users in the population ages 18-64 would be approximately 1 million Americans (95% CI: 800,000-1,200,000), with once-per-night MOTN users representing approximately 550,000 (95% CI: 450,000-650,000) Americans in the same age range.

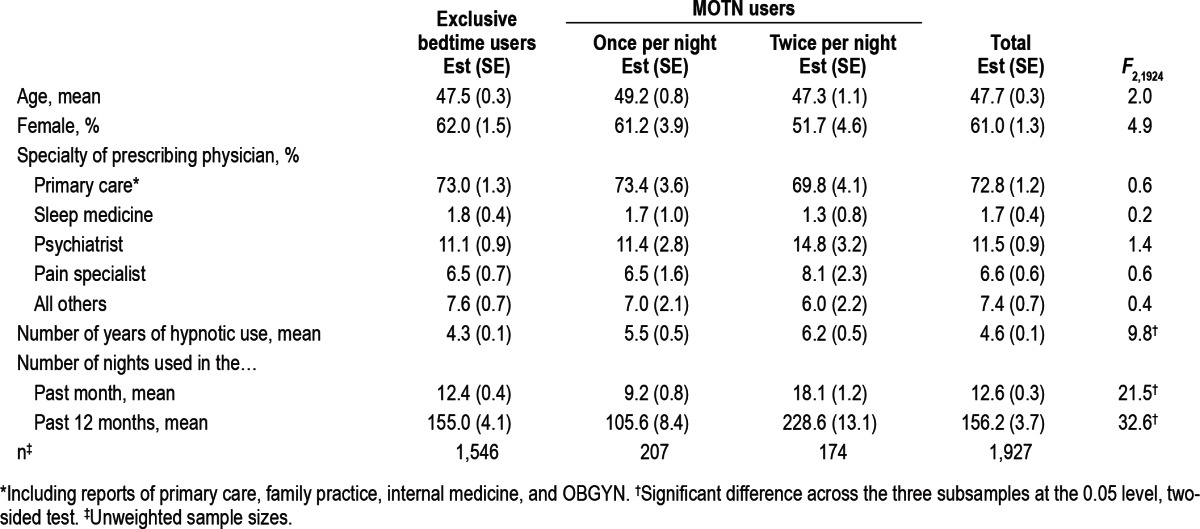

Comparison of Once-per-Night MOTN Users with Exclusive Bedtime Users

MOTN users in the Part I sample did not differ significantly from exclusive bedtime users in average age (F2,1924 = 2.0, p = 0.13), percent females (F2,1924 = 4.9, p = 0.08), or the specialty of the physician who most recently prescribed their sleep medication (F2,1924 = 0.2-1.4, p = 0.49-0.91; Table 3). However, mean number of years of hypnotic use was significantly longer for MOTN users (5.5 years for once-per-night MOTN users and 6.2 years for twice-per-night MOTN users) than for exclusive bedtime users (4.3 years; F2,1924 = 9.8, p < 0.001). MOTN users also differed significantly from exclusive bedtime users in frequency of hypnotic use. Frequency of use was significantly lower among once-per-night MOTN users (means of 9.2 nights in the past month and 105.6 in the past 12 months) than exclusive bedtime users (means of 12.4 nights in the past month, F1,1925 = 14.4, p < 0.001; and 155.0 in the past 12 months, F1,1925 = 28.1, p < 0.001), but significantly higher among twice-per-night MOTN users than exclusive bedtime users (means of 18.1 nights in the past month and 228.6 in the past 12 months, F1,1925 = 22.1-28.1, p < 0.001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and treatment profiles of exclusive bedtime users, once-per-night MOTN users, and twice-per-night MOTN users in the Part I sample (n = 1,927)

In the Part II sample, once-per-night MOTN users were asked how many times they used MOTN in the past month (30 nights). The mean was 2.8 (0.4) compared to the 9.2 mean for overall monthly use. This means that the majority (70%) of use among once-per-night MOTN users is at bedtime rather than MOTN.

Doctor Recommendations and Personal Rules for Once-per-Night MOTN Use

Only a small minority of once-per-night MOTN users (14.0% [2.9]) reported that the doctor who prescribed their sleep medicine advised them to use it in the middle of the night to resume sleep. However, the proportion of patients reporting such directions for use varies significantly by type of provider (χ24 = 20.5, p < 0.001), due to much higher proportions of reported doctor advice to use MOTN among once-per-night MOTN users treated by a sleep medicine specialist (52.6% [35.3]) or psychiatrist (42.6% [13.3]) than by a primary care doctor (9.6% [2.9]), pain specialist (13.6% [7.5]), or other doctor (5.2% [5.2]).

The vast majority of once-per-night MOTN users (86.0% [2.6]) reported having a personal rule for MOTN use. By far the most common rules either involved amount of time left in bed, such as not using MOTN unless expecting to be in bed ≥ 6 h after taking the medication (69.5% [3.5]) and/or involved next-day demands (such as not using MOTN unless it was possible to sleep in the next morning (73.2% [3.5]). Presence vs. absence of a rule for use was not significantly related to whether or not MOTN use was based on doctors' advice (t = 1.8, p = 0.071). Nor was presence vs. absence of a rule significantly related either to frequency of MOTN use (3.4 [0.5]/month with a rule vs. 4.6 [1.6]/month without a rule; t = 0.7, p = 0.48) or to the mean individual-level proportion of overall hypnotic use that was MOTN (44.4% [3.4] with a rule vs. 48.6% [10.3] without a rule; t = 0.4, p = 0.70).

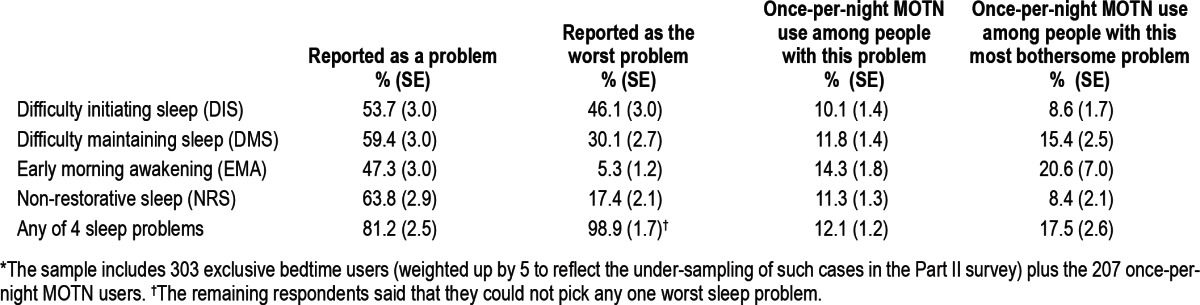

Nighttime Sleep Problems among Exclusive Bedtime versus Once-per-Night MOTN Users

Types of sleep problems were assessed only in the Part II sample. NRS was the most commonly reported nighttime sleep problem (reported by 63.8% of Part II respondents), followed by DMS (59.4%), DIS (53.7%), and EMA (47.3%; Table 4) The sum of these 4 percentages is greater than 100%, which means that the typical respondent with sleep problems had more than one symptom. However, only 81.2% of respondents reported any of these 4 symptoms, the remaining 18.8% reporting that feeling tired during the day was their only sleep problem. DIS was reported as the most bothersome sleep problem by the largest proportion of respondents (46.1%) followed by DMS (30.1%), NRS (17.4%), and EMA (5.3%).

Table 4.

Distribution of sleep problems and proportional once-per-night MOTN medication use by type of sleep problem in the Part II sample* (n = 510)

The proportion of respondents in Part II of the sample who are once-per-night MOTN users is 12.3%. (This is higher than the 11.2% in Table 2 because twice-per-night MOTN users were included in the Table 1 calculation but are excluded in Part II of the sample.) This proportion is higher among respondents in the Part II sample who reported EMA (14.3%) than other nighttime sleep problems (10.1% to 11.8%; Table 4). The situation is somewhat different in the subsamples of respondents who reported specific sleep problems as their most bothersome, where the highest proportions with once-per-night MOTN use are among those whose most bothersome problems are either EMA (20.6%) or DMS (15.4%). The proportions of once-per-night MOTN use are much lower among those whose most bothersome problems are DIS (8.6%) or NRS (8.4%).

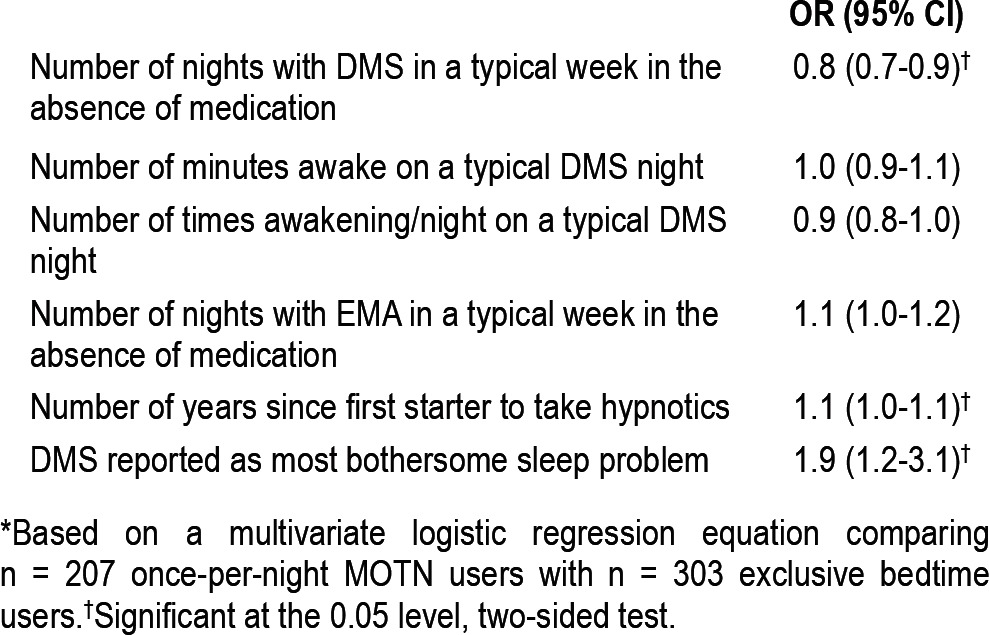

Predictors of MOTN Use

A logistic regression analysis was carried out among Part II respondents to examine significant predictors of once-per-night MOTN use from among the variables considered previously. Respondents who reported that DMS was their most bothersome sleep problem had a significantly elevated OR (95% CI) of once-per-night MOTN use (1.9 [1.2-3.1], p = 0.011), indicating that those for whom DMS was most bothersome were nearly twice as likely as others to use once-per-night MOTN rather than exclusively at bedtime (Table 5). Number of years since starting hypnotic use also had a significantly elevated OR (95% CI) with once-per-night MOTN use (1.1 [1.0-1.1], p = 0.014). Number of nights per week respondents typically experienced nighttime awakenings in the absence of medication, in comparison, was inversely related to once-per-night MOTN use (0.8 [0.7-0.9], p = 0.002). The other predictors considered in the analysis (number of nights per week with early morning waking, number of nighttime awakenings on nights when they occur, mean overall time awake at night) were all insignificant (χ21 = 0.1-2.5, p = 0.11-0.69).

Table 5.

Predictors of once-per-night MOTN medication user versus exclusive bedtime use in the Part II sample* (n = 510)

DISCUSSION

No previous research exists on the epidemiology of MOTN use in the general population. Such research is warranted, though, given the high prevalence and persistence of sleep maintenance insomnia and the suspicion that off-label MOTN use is common. The current results are the first systematic large-scale survey data to estimate the prevalence of MOTN hypnotic use in any detail. Although the external validity of findings is limited by a low response rate and the fact that the sample was restricted to insured people in the age range 18-64, results nonetheless provide a preliminary view of real-world MOTN hypnotic use patterns in the community.

Within the context of these sample constraints, the results suggest that approximately one-fifth of hypnotic users in the age range of 18 to 64 years use hypnotics off-label in the middle of the night to resume sleep. Nearly half of these MOTN users take hypnotics twice in the same night. The data also suggest that once-per-night and twice-per-night MOTN users are quite different, in that the former use hypnotics significantly less frequently than exclusive bedtime users while the latter use hypnotics significantly more frequently than exclusive bedtime users. We were unable to make more detailed comparisons of once-per-night versus twice-per-night MOTN users because the latter were excluded from Part II of the survey, but we were able to compare once-per-night MOTN users with exclusive bedtime users. The fact that once-per-night MOTN users take hypnotics at bedtime less often than exclusive bedtime users (averages of 6.4 nights/month vs. 12.4 nights/month, respectively) is indirectly consistent with the suggestion in the introduction that PRN dosing options could lead to a reduction in nightly hypnotic use among patients with a primary concern about DMS.9 However, the fact that once per month MOTN users have a longer duration of use than exclusive bedtime users might indicate an opposite long-term effect. Causal interpretations of these naturalistic associations are inappropriate, though, and can only be confirmed by controlled studies.

That twice-per-night MOTN users had much higher numbers of uses (an average of 18.1 nights/month compared to 12.4 nights/month among exclusive bedtime users) might be due to them having more complex insomnia (e.g., high rates of both DIS and DMS). Alternatively, one might speculate that twice-per-night MOTN users take hypnotics at bedtime with the intent of being able to sleep through the night, and when they awaken, despite having taken the medication at bedtime, they re-medicate. This possibility is consistent with our finding that twice-per-night MOTN users have been taking hypnotics for a longer duration than exclusive bedtime users. Although laboratory studies suggest that tolerance and dose escalation is not a significant issue with hypnotics,23 it may be that long-term users habituate to the sedative effects of prescription hypnotics and experience “breakthrough” sleep maintenance symptoms, which then need a second medication dosing for adequate coverage. Such speculations, however, extend beyond the data available here.

We found that the vast majority of once-per-night MOTN users switch between bedtime use and MOTN use, with MOTN use occurring much less often than bedtime use (on average of 2.8 MOTN uses/month compared to an average of 6.4 bedtime uses/month). Frequency of MOTN use among patients who use twice a night was not determined, as they were not included in Part II of the survey. However, as twice-per-night MOTN dosing occurs much more frequently than once-per-night MOTN dosing (an average of 18.1 in the past 30 days among twice-per-night MOTN users compared to 9.2 among once-per-night MOTN users) and are almost as numerous as once-per-night MOTN users (9.0% vs. 11.2% of all hypnotic users), it is not implausible that the rate of overall MOTN use among twice-per-night MOTN users in the age range of the sample might accumulate to twice that of once-per-night MOTN users. This would put the total annual number of MOTN uses in this age range in the country as a whole at well over 50 million if we assumed that sample estimates apply to the total population and that the proportion of the population using prescription hypnotics is consistent with previous national estimates.30–32

This high estimated rate of off-label MOTN use is perhaps expectable in light of broader evidence that insomniacs frequently use alcohol, over-the-counter medications, and a variety of prescription medications other than hypnotics to self-medicate their sleep problems,33 along with evidence that sleep maintenance insomniacs are particularly prone to self-medication.34 We found that only a small proportion of once-per-night MOTN users (14.0%) reported that their MOTN use was on the advice of a physician, although this physician advice was reported by patients to be much more common among once-per-night MOTN users treated by a sleep medicine specialist or psychiatrist than by other practitioners. Being mindful that this result is based on patient self-report, it is possible that specialists in sleep medicine and psychiatry are more sophisticated than other practitioners regarding sleep psychopharmacology, more familiar with newer short-acting hypnotic agents, and more comfortable prescribing them for MOTN use. However, such speculations are beyond the scope of the current data. One thing is clear, though, regarding the implications of the overall low rate of physician recommendation in light of the potential adverse effects of off-label MOTN hypnotic use: that prescribing physicians should routinely ask patients with hypnotic prescriptions about possible MOTN use and caution them against off-label MOTN use. Although we are aware of no controlled studies on the effects of such an intervention, experimental studies of the basic psychological processes underlying treatment adherence suggest that physician efforts to help patients understand the rationale for discouraging off-label hypnotic use could lead to substantial reductions.35

Comparison of once-per-night MOTN users with exclusive bedtime users found only three significant correlates: DMS as a most bothersome sleep problem, long duration of hypnotic use, and low weekly frequency of DMS. The first two of these three associations are easily interpreted, as we might expect patients to be more aggressive in self-medicating problems they consider most bothersome and as they become more familiar with medication effects over time. It is somewhat more diffi-cult to understand the finding that frequency of DMS is lower among MOTN users than exclusive bedtime users. This might be a chance finding in the many comparisons made here, or suggest either an especially high rate of habituation among chronic maintenance insomniacs or a lower severity threshold for self-medication among MOTN users than other hypnotic users, perhaps due to the intermittent character of symptoms. Evidence consistent with the possibility of lower symptom tolerance has been reported in a study of predictors of sham self-medication,34 but future research is needed to determine the extent to which this accounts for the association of MOTN use with low DMS frequency. Future research is also needed to examine other predictors of off-label MOTN use, such as the presence and severity of comorbid physical and mental disorders.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The research reported here was funded by Transcept Pharmaceuticals and the work was performed at EPI-Q, Inc. Dr. Roth has served as a consultant for Abbott, Accadia, Acogolix, Acorda, Actelion, Addrenex, Alchemers, Alza, Ancel, Arena, Astra-Zenca, Aventis, AVER, Bayer, BMS, BTG, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, Eisai, Elan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, Glaxo Smith Kline, Hypnion, Impax, Intec, Intra-Cellular, Jazz, Johnson and Johnson, King, Lundbeck, McNeil, MediciNova, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Orexo, Organon, Otsuka, Prestwick, Proctor and Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Resteva, Roche, Sanofi, SchoeringPlough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Yanda, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport. He has served on speakers bureau for Purdue and Sepracor. He has received research support from Apnex, Aventis, Cephalon, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, SchoeringPlough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, Transcept, Wyeth, and Xenoport. Ms. Berglund has participated in research activities supported by Dr. Kessler's grants, which have included research funding from Pfizer, SanofiAventis, Shire, and Janssen. Ms. Berglund has no financial interest in any of these organizations. Dr. Shahly is an employee of the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School. That program has received research funding from Pfizer, SanofiAventis, Shire Development, Inc., and Janssen Pharmceutica, N.V. Dr. Shahly has no financial interest in any of these organizations. Dr. Shillington is an employee and shareholder in the company Epi-Q, Inc. Epi-Q provides project management service and has received grant and consulting support from the following companies: Merck, Cephalon, Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer, Biogen-IDEC, Onconova, AstraZeneca, Glaxo Smith Kline, Novartis, Roche, Ortho McNeil, Takada, Transcept, Lundbeck Genentech, Bayer, Baxter, and Abbott. Dr. Shillington receives no direct compensation as a result of grants or contracts, other than her salary from Epi-Q. Dr. Stephenson is an employee of HealthCore, Inc., a research and consulting organization. All of her research activities are industry-sponsored. However, she receives no direct compensation as a result of grants or contracts, other than her salary from Health Core. Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Analysis Group, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerner-Galt Associates, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline Inc., HealthCore Inc., Health Dialog, Integrated Benefits Institute, John Snow Inc., Kaiser Permanente, Matria Inc., Mensante, Merck & Co, Inc., Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc., Primary Care Network, Research Triangle Institute, Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shire US Inc., SRA International, Inc., Takeda Global Research & Development, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Appliance Computing II, Eli Lilly & Company, Mindsite, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Plus One Health Management and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has had research support for his epidemiological studies from Analysis Group Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, EPI-Q, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs., Pfizer Inc., Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, and Shire US, Inc.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research reported here was funded by Transcept Pharmaceuticals. The study was designed by Kessler and Roth. The survey instrument was developed by Kessler, Roth, Shahly, and Shillington. Shahly and Shillington supervised data collection. All coauthors collaborated in planning data analyses and interpreting results. Kessler supervised data analyses and Berglund carried out the analyses. Roth and Shahly prepared the first draft of the manuscript and all coauthors collaborated in making revisions. All coauthors are fully responsible for content and editorial decisions. Transcept played no role in data collection or management other than in posing the initial research question and providing operational and financial support. Transcept played no role in data analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors thank Marcus Wilson and his staff at HealthCore, Inc. for use of the Health-Core research environment and calculation of population rates of sleep medication use, the staff of EPI-Q, Inc. for study management, and Marielle Weindorf and her staff at DataStat, Inc. for carrying out the survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lichstein KL, Taylor DJ, McCrae CS, Ruiter ME. Insomnia: epidemiology and risk factors. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2011. pp. 827–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JK, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al. Nighttime insomnia symptoms and perceived health in the America Insomnia Survey (AIS) Sleep. 2011;34:997–1011. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM. Nocturnal awakenings and comorbid disorders in the American general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morin CM, Belanger L, LeBlanc M, et al. The natural history of insomnia: a population-based 3-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:447–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolge SC, Joish VN, Balkrishnan R, Kannan H, Drake CL. Burden of chronic sleep maintenance insomnia characterized by nighttime awakenings. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13:15–20. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hara C, Stewart R, Lima-Costa MF, et al. Insomnia subtypes and their relationship to excessive daytime sleepiness in Brazilian community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2011;34:1111–7. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neubauer DN. The evolution and development of insomnia pharmacotherapies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:S11–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg RP. Sleep maintenance insomnia: strengths and weaknesses of current pharmacologic therapies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18:49–56. doi: 10.1080/10401230500464711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth T, Zammit GK, Scharf MB, Farber R. Efficacy and safety of as-needed, post bedtime dosing with indiplon in insomnia patients with chronic difficulty maintaining sleep. Sleep. 2007;30:1731–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips BA. Insomnia, hypnotic drug use, and patient well-being: first, do no harm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:417–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farber RH, Burke PJ. Post-bedtime dosing with indiplon in adults and the elderly: results from two placebo-controlled, active comparator crossover studies in healthy volunteers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:837–46. doi: 10.1185/030079908X273327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zammit G, Wang-Weigand S, Rosenthal M, Peng X. Effect of ramelteon on middle-of-the-night balance in older adults with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:34–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zammit GK, Corser B, Doghramji K, et al. Sleep and residual sedation after administration of zaleplon, zolpidem, and placebo during experimental middle-of-the-night awakening. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:417–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth T, Hull SG, Lankford DA, Rosenberg R, Scharf MB. Low-dose sublingual zolpidem tartrate is associated with dose-related improvement in sleep onset and duration in insomnia characterized by middle-of-the-night (MOTN) awakenings. Sleep. 2008;31:1277–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth T, Mayleben D, Corser BC, Singh NN. Daytime pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic evaluation of low-dose sublingual transmucosal zolpidem hemitartrate. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:13–20. doi: 10.1002/hup.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leufkens TR, Lund JS, Vermeeren A. Highway driving performance and cognitive functioning the morning after bedtime and middle-of-the-night use of gaboxadol, zopiclone and zolpidem. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:387–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verster JC, Veldhuijzen DS, Patat A, Olivier B, Volkerts ER. Hypnotics and driving safety: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials applying the on-the-road driving test. Curr Drug Saf. 2006;1:63–71. doi: 10.2174/157488606775252674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verster JC, Volkerts ER, Olivier B, Johnson W, Liddicoat L. Zolpidem and traffic safety - the importance of treatment compliance. Curr Drug Saf. 2007;2:220–6. doi: 10.2174/157488607781668882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Logan BK, Couper FJ. Zolpidem and driving impairment. J Forensic Sci. 2001;46:105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustavsen I, Al-Sammurraie M, Morland J, Bramness JG. Impairment related to blood drug concentrations of zopiclone and zolpidem compared to alcohol in apprehended drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41:462–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones AW, Holmgren A, Kugelberg FC. Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:248–60. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pressman MR. Sleep driving: sleepwalking variant or misuse of z-drugs? Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:285–92. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendelson WB, Roth T, Cassella J, et al. The treatment of chronic insomnia: drug indications, chronic use and abuse liability. Summary of a 2001 New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting symposium. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:7–17. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al. Reliability and validity of the brief insomnia questionnaire in the America insomnia survey. Sleep. 2010;33:1539–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of propensity scores in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolter KM. Introduction to variance estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2008. SAS/STAT software, version 9.2 for Unix. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. Behavioral risk factor survey surveillance system. BRFSS annual survey data. Summary data quality reports. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. The beneficial and adverse effects of hypnotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(Suppl):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. Insomnia and its treatment. Prevalence and correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:225–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790260019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Kassam A, Sabapathy CD. Pharmacoepidemiology of benzodiazepine and sedative-hypnotic use in a Canadian general population cohort during 12 years of follow-up. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:792–9. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institute of Health NIH state-of-the-science conference statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2005;22:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roehrs T, Bonahoom A, Pedrosi B, Rosenthal L, Roth T. Disturbed sleep predicts hypnotic self-administration. Sleep Med. 2002;3:61–6. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meichenbaum D, Turk DC. Facilitating treatment adherence. New York: Plenum; 1987. [Google Scholar]