Abstract

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PcP) is a serious fungal infection among immunocompromised patients. In developed countries, the epidemiology and clinical spectrum of PcP have been clearly defined and well documented. However, in most developing countries, relatively little is known about the prevalence of pneumocystosis. Several articles covering African, Asian and American countries were reviewed in the present study. PcP was identified as a frequent opportunistic infection in AIDS patients from different geographic regions. A trend to an increasing rate of PcP was apparent in developing countries from 2002 to 2010.

Keywords: Pneumocystis, HIV, opportunistic infection, developing countries

Abstract

La pneumonie due à Pneumocystis jirovecii (PcP) est une infection mycosique sévère chez les patients immunodéprimés. Dans les pays développés, les données épidémiologiques et cliniques de la PcP sont bien documentées. En revanche, dans les pays en voie de développement, on dispose de peu d’informations concernant la prévalence de la pneumocystose. De nombreux articles qui concernent des pays d’Afrique, d’Asie et d’Amérique sont passés en revue dans ce travail. La PcP est une infection opportuniste fréquente chez les patients atteints de sida dans différentes régions géographiques. Une tendance à l’augmentation de l’incidence de la PcP a été observée dans les pays en développement entre 2002 et 2010.

Keywords: Pneumocystis, VIH, infection opportuniste, pays en développement

Introduction

Pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii (PcP) (previously known as P. carinii) has long been recognized in patients with impaired immunity. It was initially described as a cause of epidemic interstitial pneumonia in premature and malnourished infants. Until 1980, PcP was uncommon and recognized in patients who were immunocompromised because of malignancies, immunosuppressive therapy, or congenital immunodeficiencies. However, the rate of infection by P. jirovecii increased with the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Calderón et al., 2002).

Despite a decline in the incidence of PcP in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), it remains a common and serious opportunistic disease in HIV-infected individuals. In developed countries, the epidemiology and clinical spectrum of PcP have been clearly defined and well documented. In contrast, a limited number of epidemiological studies have evaluated PcP prevalence in developing countries (Morris et al., 2004).

Fisk and colleagues previously reviewed changes in PcP rates among HIV patients in Africa, Asia, India, the Philippines, and in Central and South America. They found a greater percentage of PcP was described compared to the results of earlier studies, indicating that PcP is a significant AIDS-related opportunistic infection (OI) in many developing countries (Fisk et al., 2003).

Recent reports have described an increased rate of PcP in Africa, Asia and South America (Worodria et al., 2003; Aderaye et al., 2007; Le Minor et al., 2008; Panizo et al., 2008; Vray et al., 2008). In this study, we review published studies that have reported the frequency of PcP in developing countries, focusing mainly on more recent data.

PcP in Africa

PcP was initially thought to be a rare manifestation of AIDS in Africa (Elvin et al., 1989). In Uganda, pneumocystosis was not detected among AIDS patients (Serwadda et al., 1989). Also, while a study of HIVinfected black adults in South Africa found that only one (0.6%) out of 181 patients had PcP (Karstaedt, 1992). On the other hand, rates of 3.6 to 11% were reported for Tanzania, Congo and Ivory Coast in the first decade of the AIDS epidemic (Carme et al., 1991; Lucas et al., 1991; Abouya et al., 1992; Atzori et al., 1993).

Other studies, however, have demonstrated higher rates of PcP in populations on the African continent. In Zimbabwe, PcP was identified by methenamine silver staining in bronchoalveolar lavage samples in 33% of 64 patients with respiratory symptoms who were sputum smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) (Malin et al., 1995). In Kenya, P. jirovecii was detected by immunofluorescence and toluidine blue staining in respectively 37.2 and 27.4% of 51 HIV/AIDS patients with bilateral pulmonary shadows who were sputum smear-negative for AFB (Chakaya et al., 2003). In a study of African miners in South Africa, PcP incidence at the time of autopsy increased progressively from 9/1,000 in 1996 to 66/1,000 in 2000 (Wong et al., 2006). Also, in an Ethiopian population, PcP was detected by polymerase chain reaction in 42.7% of 131 HIV-infected patients with atypical chest X-ray findings and whose sputum was smear-negative for AFB (Aderaye et al., 2008).

P. jirovecii is a common cause of pneumonia in HIVinfected children ages 3-6 months but is less common and less severe in children over age 12 months (Chintu et al., 2002, Jeena et al., 2005). In African children, PcP is an opportunistic pneumonia that is frequently related to HIV infection, and several reports have revealed high rates of PcP in this population. In Zimbabwe, lung biopsies from 24 HIV-seropositive children who died of pneumonia in 1995 were examined in an autopsy study using histology, culture, microscopy and polymerase chain reaction, and Pneumocystis was detected in 16 (67%) children (Nathoo et al., 2001). In another study of autopsies carried out in Ivory Coast, PcP was the cause of death in 31% of children under 15 months of age infected with HIV (Lucas et al., 1996). In addition, 31% of all deaths and 48% of infant deaths ≤ one year, according to an autopsy study of HIV-positive children in Botswana, were caused by pneumocystosis (Ansari et al., 2003).

Detection of P. jirovecii has been reported in clinical specimens collected by noninvasive methods in Africa. Cysts were identified in the induced sputum and nasopharyngeal aspirates in 51 of 105 (48.6%) children using immunofluorescence staining (Ruffini et al, 2002) and P. jirovecii DNA was detected by PCR amplification in 15 of 22 (68%) oropharyngeal mouth washes from children who died from AIDS-related PcP (Lishimpi et al., 2002).

PcP in Asia

In Thailand, fewer than 100 cases of PcP per year were described before 1992. However, there was a marked increase in the incidence of cases reported to the Thai Ministry of Public Health, which peaked at 6,255 cases per year in 2000 (Sritangratanakul et al., 2004). In a retrospective study, PcP was diagnosed in 18.7% of 286 HIV/AIDS patients (Anekthananon et al., 2004). In a prospective study, tuberculosis (TB) was the most common diagnosis (44%), followed by PcP (25.4%) and bacterial pneumonia (20.3%) in 59 HIV/AIDS patients with interstitial infiltrates on chest radiographs (Tansuphasawadikul et al., 2005). Further diagnosis of PcP using a noninvasive method (e.g. induced sputum) was documented by polymerase chain reaction in 21% of 52 HIV/AIDS patients suspected of PcP (Jaijakul et al., 2005). In addition, there was a high mortality among patients with acute respiratory failure caused by PcP in Thailand (Boonsarngsuk et al., 2009).

In Cambodia, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has become a major issue in recent years (Bendick et al., 2002). In one study, a total of 381 cases of HIV-infected patients admitted to a public hospital in Phnom Penh between 1999 and 2000 were reviewed, and chronic diarrhea was the most frequent (41.2%) HIV-related problem, whereas PcP was identified in only 8.4% of the patients (Senya et al., 2003). Also, studies have documented low rates of PcP in Vietnam (Louie et al., 2004; Klotz et al., 2007). More recently, PcP was detected in 52-55% of HIV-infected patients with smear-negative sputum for AFB in Cambodia and Vietnam, suggesting that this pneumonia might be a major concern in this region (Le Minor et al., 2008).

Several studies conducted in India have shown a low number of PcP cases, with rates of 5-6.1% described in some reports (Lanjewar et al., 2001; Kumarasamy et al., 2003; Rajagopalan et al., 2009). On the other hand, PcP was found to be an AIDS-defining illness with significant mortality among HIV-infected patients in the HAART era in another report (Kumarasamy et al., 2010). Improved detection of P. jirovecii using PCR in several respiratory specimens from HIV-infected and non-infected Indian patients with lung infiltrates and clinical features of PcP has been described, with sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 99% for PCR, and 30.7% and 100% for microscopy by Gomori methenamine silver staining (Gupta et al., 2007). Nested- PCR for the gene encoding the large-subunit rRNA (mtLSUrRNA) also has proved to be a very sensitive tool for P. jirovecii detection (Gupta et al., 2009).

PcP in the Americas

• Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean islands

Little is known about Pneumocystis infection in Central America. To date, few studies on PcP have been reported for this region. In Mexico, one of the first studies was conducted at four hospitals between March 1984 and January 1989, and Pneumocystis infection was diagnosed in 24% of 177 AIDS patients. Cytomegalovirus (69%) and TB (25%) were the most common infections (Mohar et al., 1992). Similar rates of PcP were found in an autopsy study of 58 AIDS patients (Jessurun et al., 1990).

The first case of AIDS in Panama was confirmed in 1985. Ten years later, pulmonary pneumocystosis was diagnosed by bronchoalveolar analysis in 46% of HIV-infected patients with respiratory symptoms (Rodríguez et al., 1996).

Research evaluating PcP in Guatemala found that 52 HIV-infected patients admitted to the Adult Outpatient Clinic of the San Juan de Dios General Hospital had opportunistic infections (OIs), and 14 (27%) of them were diagnosed with PcP. The results of this clinical study, performed between January 1991 and June 1992, suggest that limitations in the diagnostic and laboratory facilities of the hospital hindered the identification of some OIs (Estrada et al., 1992).

The first cases of PcP in Cuba were reported in 1969 (Rodriguez-Vigil et al., 1969). Pneumocystis infection was described in malnourished children, indicating that professionals must be aware of PcP while treating this population in health services in developing countries (Razón et al., 1977). A PcP rate of 45% was described in 40 HIV-infected Cuban patients based on clinical signs, symptoms and chest radiographs (Menéndez Capote et al, 1992). An autopsy study carried out in the same country showed pneumocystosis in 32% of 211 HIV patients with severe immunosuppression (Arteaga et al., 1998).

In Barbados, PcP was diagnosed in 37.8% of 47 children also diagnosed with HIV between 1981 and 1995. This OI was the most common (65.2%) cause of death in this population with a mortality rate that was higher among those patients diagnosed in infancy compared to those diagnosed in post-infancy (Kumar et al, 2000; St John et al., 2003).

In a study of a Haitian population, Pitchenik and colleagues found pneumocystosis in 35% of AIDS patients (Pitchenik et al., 1983). On the other hand, only two patients with PcP among 29 AIDS patients were reported from another study in Haiti (Malebranche et al., 1983).

The clinical spectrum of the AIDS epidemic was described for Puerto Rico, and the three main diagnoses for AIDS, as reported by the local AIDS Surveillance Program from 1981 to 1999, were wasting syndrome (30.7%), esophageal, bronchial and pulmonary candidiasis (29.4%) and PcP (26.8%) (Gomez et al., 2000). Of the 377 pediatric AIDS cases reported between 1981 and 1998 on the island, PcP accounted for 23% and was the most common AIDS-defining condition in the referred population (Perez-Perdomo et al., 1999). Moreover, PcP affected 49 out of 100 HIV adult patients who died from AIDS in this region between 1982 and 1991 (Climent et al., 1994). In addition, a high prevalence of PcP was observed in 1,308 HIVpositive injection-drug users in Puerto Rico from 1992 to 2005 (Baez Feliciano et al., 2008).

• South America

Several reports have been published in Venezuela, Brazil and Chile (Panizo et al., 2008; Soeiro et al., 2008). Also, investigations have been conducted in Argentina and Peru (Bava et al., 2002; Eza et al., 2006).

The epidemiology of pneumocystosis was reviewed in Venezuela, and PcP was found in 36.6% of HIVinfected patients with respiratory symptoms treated between 2001 and 2006, also suggesting that PcP must be suspected in other populations (e.g. cancer patients) with signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection (Panizo et al., 2008).

In 2002, Argentina had the sixth largest number of cumulative pediatric cases of AIDS in the Americas. Therefore, unsurprisingly, PcP had a significant influence on their health services. A study of 389 children at risk for or infected with HIV-1 conducted from February 1990 to June 1997 found that severe bacterial infection and PcP were the most common AIDS-defining conditions and death-related diseases among AIDS patients (Fallo et al., 2002). Another study demonstrated a high rate of PcP (35%) among AIDS patients in intensive care units (Bava et al., 2002). Although the comparison of the pre and post-HAART era in Argentine AIDS patients revealed an increased PcP rates from 5.9% to 9.4%, TB was the main cause of hospital admission for HIV patients in both study periods (Pérez et al., 2005).

The first cases of infection by Pneumocystis in Chile were described in 1960 in patients with interstitial plasma cell pneumonias (Bustamante et al., 1960). Later, PcP was the most common lung disease in HIV-infected patients, causing 37.7% of respiratory episodes in 236 assessed patients (Chernilo et al., 2005).

AIDS is a significant public health problem in Brazil, with 362,364 cases reported as of June 2004 and an estimated total of over 600,000 HIV-infected adults at that time (Wissmann et al., 2006). In one study, among 35 HIV-positive patients with respiratory symptoms, PcP was the most frequently identified AIDS-related disease (55%) followed by TB (41%) (Weinberg et al., 1993). Another study detected pneumocystosis in 27% of 250 HIV/AIDS patients who died from respiratory acute failure in São Paulo between 1990 and 2000 (Soeiro et al., 2008). The introduction of HAART in Brazil led to a significant change in the AIDS scenario. A total of 2,821 cases were assessed in 18 Brazilian cities, with TB (26%) being more frequent than PcP (14%) as AIDS-defining condition, possibly in part because of the anti-PcP prophylaxis used (Marins et al., 2003).

The use of newer and more potent immunosuppressive agents has been associated with PcP unrelated to AIDS in developed countries (Sepkowitz et al., 2002). Radisic and colleagues observed 17 cases of PcP in kidney transplant recipients in Argentina between July 1994 and July 2000 (Radisic et al., 2003) and more studies focusing on this point are necessary in developing areas.

Discussion

In the present study, we reviewed several articles that described Pneumocystis infection in developing countries (Table I). Significant rates of PcP have been reported that show P. jirovecii as a pathogen that causes a common OI in AIDS patients in many countries.

Table I.

Pneumocystis pneumonia in developing countries.

| Country (Years) | Patient population | PcP patients/total (%) | PcP diagnosis | HAART coverage rate * | PcP chemoprophylaxis | PcP mortality rates | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||||||

| Uganda (1999-2000) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 32/83 (39) | DFA on BAL | 33% | 25% | NA | Worodria et al., 2003 |

| Kenya (1999-2000) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 19/51 (37) | TBS and DFA on BAL | 38% | All patients within five days prior or after the bronchoscopy procedure | 26.3% | Chakaya et al., 2003 |

| Ethiopia (2004-2005) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 39/131 (30) | DFA on sputum and BAL | 29% | NA | NA | Aderaye et al., 2007 |

| Ethiopia (2004-2005) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory disease | 56/131 (43) | PCR on sputum and BAL | 29% | NA | NA | Aderaye et al., 2008 |

| Botswana (1997-1998) | AIDS | 11/35 (31) | Histopath, H & E and GS stains | 79% | NA | 28.6% | Ansari et al., 2003 |

| Zambia (1997-2000) | HIV dying with respiratory disease | 52/180 (29) | Histopath, H & E and MS stains | 46% | NA | 29% | Chintu et al., 2002 |

| Zambia (NA) | AIDS dying with respiratory disease | 15/22 (68) | PCR on OMW | 46% | NA | 68% | Lishimpi et al., 2002 |

| Senegal (2002-2005) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 135/317 (43) | DFA on IS and BAL | 56% | 19% | 19% | Vray et al., 2008 |

| Central African Republic (2002-2005) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 135/317 (43) | DFA on IS and BAL | 21% | 40% | 16% | Vray et al., 2008 |

| Malawi (2002-2004) | HIV with respiratory symptoms | 6/660 (1) | DFA and real time PCR on IS | 35% | NA | NA | van Oosterhout et al., 2007 |

| Asia (1) | |||||||

| Thailand (2000-2006) | HIV with respiratory symptoms | 8/14 (57) | DFA and Giemsa stain on BAL and TBBx | 61% | 7% | 64% | Boonsarngsuk et al., 2009 |

| Thailand (2002) | HIV/AIDS without respiratory symptoms | 53/286 (19) | Clinical diagnosis | 61% | 28.2% | NA | Anekthananon et al., 2004 |

| Thailand (2002-2003) | HIV/AIDS with respiratory symptoms | 15/59 (25) | Clinical diagnosis | 61% | NA | NA | Tansuphasawadikul et al., 2005 |

| Thailand (NA) | HIV/AIDS with respiratory symptoms | 11/52 (21) | Giemsa stain and PCR on IS | 61% | NA | NA | Jaijakul et al., 2005 |

| Cambodia (1999-2000) | AIDS without respiratory symptoms | 32/381 (8) | CXR finding and exclusion of other common causes of pneumonia | 67% | 100%** | NA | Senya et al., 2003 |

| Cambodia (2002-2004) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 84/160 (53) | DFA on BAL | 67% | 39% | 23% | Le Minor et al., 2008 |

| Cambodia (NA) | HIV/AIDS without respiratory symptoms | 20/101 (20) | Clinical diagnosis | 67% | NA | NA | Bendick et al., 2002 |

| Vietnam (2000) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 5/100 (5) | DFA on IS | 26% | 4% | 20% | Louie et al., 2004 |

| Vietnam (2002-2004) | HIV/AFB smear negative with respiratory symptoms | 38/69 (55) | DFA on BAL. | 26% | 7% | 4% | Le Minor et al., 2008 |

| Asia (2) | |||||||

| India (1996-2000) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 36/594 (6) | Standard clinical definitions and by laboratory procedures | NA | NA | 28.8% | Kumarasamy et al., 2003 |

| India (1996-2008) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 11/51 (22) | Assess clinical | NA | NA | 22% | Kumarasamy et al., 2010 |

| India (2004-2006) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 5/100 (5) | Assess clinical and laboratory findings | NA | 100% | 2% Rajagopalan et al., 2009 | |

| North America | |||||||

| Mexico (1984-1989) | HIV without respiratory symptoms AIDS | 43/177 (24) | Histopath, H & E and GS stains | 57% | NA | 24% | Mohar et al., 1992 |

| Central America | |||||||

| Panama (1995) | HIV with respiratory symptoms | 25/55 (46) | MS | 56% | NA | NA | Rodriguez et al., 1996 |

| Guatemala (1991-1992) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 14/52 (27) | Clinically | 37% | NA | NA | Estrada et al., 1992 |

| Caribbean Islands | |||||||

| Cuba (1986-1995) | AIDS | 30/93 (32) | Histopath, H & E and GS stains | > 95%. | NA | 4.5% | Arteaga et al., 1998 |

| Cuba (1988-1989) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 18/40 (45) | Clinically and radiologically | > 95%. | NA | NA | Menendez-Capote et al., 1992 |

| Barbados (1981-1995) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 18/47 (38) | Clinically | NA | NA | 65.2% | Kumar et al, 2000 |

| Haiti (1980-1982) | AIDS without respiratory symptoms | 7/20 (35) | Histopath or by TBBx | 41% | NA | 28% | Pitchenik et al., 1983 |

| Puerto Rico (1992-2005) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 20/143 (14) | Clinically | NA | NA | NA | Báez-Feliciano et al., 2008 |

| South America | |||||||

| Venezuela (2001-2006) | AIDS with respiratory symptoms | 15/41 (37) | DFA on sputum, induced sputum and BAL | NA | NA | NA | Panizo et al., 2008 |

| Peru (1999-2004) | HIV/AIDS without respiratory symptoms | 2/16 (13) | Histopath, H & E and GS stains | 48% | NA | 12.5% | Eza et al., 2006 |

| Argentina (1990-1997) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 79/226 (35) | Clinical status | 73% | NA | 21.6% | Fallo et al., 2002 |

| Argentina (1995-1996) and (2000-2001) | HIV without respiratory symptoms | 22/233 (9) | Clinical status | 73% | NA | NA | Pérez et al., 2005 |

| Chile (1999-2003) | HIV with respiratory disease | 89/236 (38) | Histopath, stains and PCR | 82% | 18% | 22% | Chernilo et al., 2005 |

| Brazil (1990-2000) | HIV/AIDS dying respiratory disease | 68/250 (27) | Histopath, H & E and GS stains | 80%. | NA | 27% | Soeiro et al., 2008 |

Notes: AFB, acid fast bacilli; DFA, direct fluorescent antibody test; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; NA, not available; IS, induced sputum; TBS, Toluidine Blue Stain; H & E, hematoxylin and eosin stain; MS, methenamine silver stains; GS, Grocott silver stain; OMW, oropharyngeal mouth wash; CXR, chest X-rays; TBBx, transbronchial biopsy.

Global total available at WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF, Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report, September 2009: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2009progressreport/en/. Country totals available at WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF, Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report, June 2008: http://www.who. int/hiv/pub/2008progressreport/en/index.html.

Information available after hospital admission, no data previously.

Notes: DFA, direct fluorescent antibody test; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; NA, not available; H & E, hematoxylin and eosin stain; MS, methenamine silver stains; GS, Grocott silver stain; TBBx, transbronchial biopsy.

Global total available at WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF, Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report, September 2009: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2009progressreport/en/. Country totals available at WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF, Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report, June 2008: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2008progressreport/en/index.html

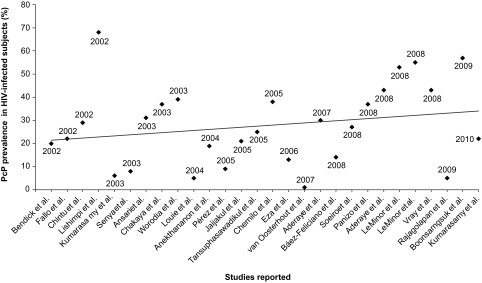

Fisk and colleagues reviewed this topic previously and showed a trend to an increasing rate of PcP in Africa from 1986 to 2000 (Fisk et al., 2003). We obtained similar data from different HIV populations in African, Asian and American countries, with a linear trend of increasing rates apparent from 2002 to 2010 (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PcP) rates among HIV-infected subjects in developing countries from 2002 until 2010.

The percentage of PcP in the HIV/AIDS population has varied among studies, however. Differences in study design, including heterogeneity in the patient population and the diverse laboratory methods used, may explain some of the variability. In this regard, the diagnosis of PcP in low-resource countries is usually clinical (Graham et al., 2001). One study found that the differential diagnosis of pneumocystosis was made by 77% of physicians on the basis of symptoms, chest radiographs and arterial blood gas analyses (Curtis et al., 1995). PcP was commonly unsuspected prior to death because clinicians misdiagnosed it as TB or bacterial pneumonia (Wong et al., 2006).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the major pathogen identified in almost all studies in developing countries. TB is frequently observed in HIV/AIDS patients with > 200 CD4+ cells/mm3 and might lead to death at an earlier stage of HIV infection. PcP rarely occurs with CD4+ cell counts > 100 mm3. Thus, PcP is an important diagnostic consideration among the most immunocompromised patients (van Oosterhout et al., 2007).

A hypothesis regarding reduced exposure to P. jirovecii in developing countries had been previously suggested (Malin et al., 1995), however, antibodies against Pneumocystis have been found in 70% of Gambian children (Wakefield et al., 1990) and DNA was detected in specimens from 45 (51.7%) of 87 infants who died in the Chilean community (Vargas et al., 2005).

Miller and colleagues suggested that different P. jirovecii genotypes may have distinct physical requirements for survival in the environment and/or for transmission (Miller et al., 2007). Moreover, differences in strains may play an important role in the pathogenesis of this infection. In Africa, genotype 3 according to the mtLSUrRNA sequence was the most frequently obtained (Miller et al., 2003). Recently, the association between genetic polymorphisms of several loci and the intensity of infection from HIV-positive patients was investigated in Europe. In that study, genotype 1 at the mtLSUrRNA was associated with less virulent cases of PcP (Esteves et al., 2010). New studies must be conducted to genotype P. jirovecii isolates from HIV patients in developing countries.

In conclusion, significant rates of PcP have been described in HIV-infected patients in the developing world. A trend to increasing rate is also evident from recent African, Asian and American studies. Finally, clinicians must bear in mind that P. jirovecii is very important in the differential diagnosis of OIs in the context of developing countries.

Footnotes

This article is based on a presentation given at the Pneumocystis discovery first centenary Conference, Brussels, 5-6 November 2009.

References

- Abouya Y.L., Beaumel A., Lucas S., Dago-Akribi A., Coulibaly G., N’Dhatz M., Konan J.B., Yapi A. & De Cock K.M.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. An uncommon cause of death in African patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis, 1992, 145, 617–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderaye G., Bruchfeld J., Aseffa G., Nigussie Y., Melaku K., Woldeamanuel Y., Asrat D., Worku A., Gaegziabher H., Lebaad M. & Lindquist L.Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and other pulmonary infections in TB smear-negative HIV-positive patients with atypical chest X-ray in Ethiopia. Scand J Infect Dis, 2007, 39, 1045–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderaye G., Woldeamanuel Y., Asrat D., Lebbad M., Beser J., Worku A., Fernandez V. & Lindquist L.Evaluation of Toluidine Blue O staining for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis jiroveci in expectorated sputum sample and bronchoalveolar lavage from HIV-infected patients in a tertiary care referral center in Ethiopia. Infection, 2008, 36, 237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anekthananon T., Ratanasuwan W., Techasathit W., Rongrungruang Y. & Suwanagool S.HIV infection/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome at Siriraj Hospital, 2002: time for secondary prevention. J Med Assoc Thai, 2004, 87, 173–179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari N.A., Kombe A.H., Kenyon T.A., Mazhani L., Binkin N., Tappero J.W., Gebrekristos T., Nyirenda S. & Lucas S.B.Pathology and causes of death in a series of human immunodeficiency virus-positive and -negative pediatric referral hospital admissions in Botswana. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2003, 22, 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga Hernández E., Capó de Paz V., Pérez Fernándezterán M.L.Opportunistic invasive mycoses in AIDS. An autopsy study of 211 cases. Rev Iberoam Micol, 1998, 15, 33–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzori C., Bruno A., Chichino G., Gatti S., Scaglia M.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and tuberculosis in Tanzanian patients infected with HIV. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 1993, 87, 55–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Báez Feliciano D.V., Gómez M.A., Fernández-Santos D.M., Quintana R., Rios-Olivares E. & Hunter-Mellado R.F.Profile of Puerto Rican HIV/AIDS patients with early and non-early initiation of injection drug use. Ethn Dis, 2008, 18, 99–104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bava A.J., Cattaneo S. & Bellegarde E.Diagnosis of pulmonary pneumocystosis by microscopy on wet mount preparations. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 2002, 44, 279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendick C., Scheifele C., Reichart P.A.Oral manifestations in 101 Cambodians with HIV and AIDS. J Oral Pathol Med, 2002, 31, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonsarngsuk V., Sirilak S. & Kiatboonsri S.Acute respiratory failure due to Pneumocystis pneumonia: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Infect Dis, 2009, 13, 59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante W., Moreno L. & Diaz M.Interstitial plasma cell pneumonias with demonstration of Pneumocystis carinii in Chile. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd, 1960, 108, 145–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Sandubete E.J., Varela-Aguilar J.M., Medranoortega F.J., Nieto-Guerrer V., Respaldiza-Salas N., de la Horra-Padilla C. & Dei-Cas E.Historical perspective on Pneumocystis carinii infection. Protist, 2002, 153, 303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carme B., Mboussa J., Andzin M., Mbouni E., Mpele P. & Datry A.Pneumocystis carinii is rare in AIDS in Central Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 1991, 85, 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakaya J.M., Bii C., Ng’Ang’A L., Amukoye E., Ouko T., Muita L., Gathua S., Gitau J., Odongo I., Kabanga J.M., Nagai K., Suzumura S. & Sugiura Y.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV/AIDS patients at an urban district hospital in Kenya. East Afr Med J, 2003, 80, 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernilo S., Trujillo S., Kahn M., Paredes M., Echevarría G.Sepúlveda C.Lung diseases among HIV infected patients admitted to the “Instituto Nacional del Torax” in Santiago Chile. Rev Med Chil, 2005, 133, 517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintu C., Mudenda V., Lucas S., Nunn A., Lishimpi K., Maswahu D., Kasolo F., Mwaba P., Bhat G., Terunuma H. & Zumla A.UNZA-UCLMS Project Paediatric Post-mortem Study Group. Lung diseases at necropsy in African children dying from respiratory illnesses: a descriptive necropsy study. Lancet, 2002, 360, 985–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Climent C., de Vinatea M.L., Lasala G., Ie S.O., Vélez R., Colón L. & Mullick F.G.Geographical pathology profile of AIDS in Puerto Rico: the first decade. Mod Pathol, 1994, 8, 248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J.R., Paauw D.S., Wenrich M.D., Carline J.D. & Ramsey P.G.Ability of primary care physicians to diagnose and manage Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med, 1995, 10, 395–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvin K.M., Lumbwe C.M., Luo N.P., Björkman A., Källenius G. & Linder E.Pneumocystis carinii is not a major cause of pneumonia in HIV infected patients in Lusaka, Zambia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 1989, 83, 553–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves F., Gaspar J., Tavares A., Moser I., Antunes F., Mansinho K. & Matos O.Population structure of Pneumocystis jirovecii isolated from immunodeficiency viruspositive patients. Infect Genet Evol, 2010, 10, 192–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada Y., Martin R.M., Molina H., Samayoa B., Carlos R., Velazquez S., Behrens E., Melgar N. & Arathoon E.Characteristics of human immunodeficiency virus infection in the San Juan de Dios General Hospita. Rev Col Med Cir Guatem, 1992, 2, 26–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eza D., Cerrillo G., Moore D.A., Castro C., Ticona E., Morales D., Cabanillas J., Barrantes F., Alfaro A., Benavides A., Rafael A., Valladares G., Arevalo F., Evans C.A. & Gilman R.H.Postmortem findings and opportunistic infections in HIV-positive patients from a public hospital in Peru. Pathol Res Pract, 2006, 202, 767–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallo A.A., Dobrzanski Nisiewicz W., Sordelli N., Cattaneo M.A., Scott G. & López E.L.Clinical and epidemiologic aspects of human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected children in Buenos Aires Argentina. Int J Infect Dis, 2002, 6, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk D.T., Meshnick S. & Kazanjian P.H.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients in the developing world who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis, 2003, 36, 70–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M.A., Fernandez D.M., Otero J.F., Miranda S. & Hunter R.The shape of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Puerto Rico. Rev Panam Salud Pública, 2000, 7, 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S.M., Coulter J.B. & Gilks C.F.Pulmonary disease in HIV-infected African children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2001, 5, 12–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Mirdha B.R., Guleria R., Mohan A., Agarwal S.K., Kumar L., Kabra S.K. & Samantaray J.C.Improved detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii infection in a tertiary care reference hospital in India. Scand J Infect Dis, 2007, 39, 571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Mirdha B.R., Guleria R., Kumar L., Samantaray J.C., Agarwal S.K., Kabra S.K. & Luthra K.Diagnostic significance of nested polymerase chain reaction for sensitive detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii in respiratory clinical specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2009, 64, 381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaijakul S., Saksirisampant W., Prownebon J., Yenthakam S., Mungthin M., Leelayoova S. & Nuchprayoon S.Pneumocystis jiroveci in HIV/AIDS patients: detection by FTA filter paper together with PCR in noninvasive induced sputum specimens. J Med Assoc Thai, 2005, 88 (Suppl 4), 294–299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeena P.The role of HIV infection in acute respiratory infections among children in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2005, 9, 708–715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessurun J., Angeles-Angeles A., Gasman N.Comparative demographic and autopsy findings in acquired immune deficiency syndrome in two Mexican populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 1990, 3, 579–583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karstaedt A.S.AIDS-the Baragwanath experience. Part III. HIV infection in adults at Baragwanath Hospital. S Afr Med J, 1992, 82, 95–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz S.A., Nguyen H.C., Pham T., Nguyen L.T., Ngo D.T. & Vu S.N.Clinical features of HIV/AIDS patients presenting to an inner city clinic in Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam. Int J STD AIDS, 2007, 18, 482–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A. & St john M.A.HIV infection among children in Barbados. West Indian Med J, 2000, 49, 43–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasamy N., Solomon S., Flanigan T.P., Hemalatha R., Thyagarajan S.P. & Mayer K.H.Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus disease in southern India. Clin Infect Dis, 2003, 36, 79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasamy N., Venkatesh K.K., Devaleenol B., Poongulali S., Yephthomi T., Pradeep A., Saghayam S., Flanigan T., Mayer K.H. & Solomon S.Factors associated with mortality among HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy in southern India. Int J Infect Dis, 2010, 14, 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanjewar D.N. & Duggal R.Pulmonary pathology in patients with AIDS: an autopsy study from Mumbai. HIV Med, 2001, 2, 266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor O., Germani Y., Chartier L., Lan N.H., Lan N.T., Duc N.H., Laureillard D., Fontanet A., Sar B., Saman M., Chan S. & L’HER P.MAYAUD C. & VRAY M. Predictors of pneumocystosis or tuberculosis in HIV-infected Asian patients with AFB smear-negative sputum pneumonia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2008, 48, 620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishimpi K., Kasolo F., Chintu C., Mwaba P., Mudenda V., Maswahu D., Terunuma H., Fletcher H., Nunn A., Lucas S. & Zumla A.Identification of Pneumocystis carinii DNA in oropharyngeal mouth washes from AIDS children dying of respiratory illnesses. AIDS, 2002, 16, 932–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie J.K., Chi N.H., Thao Le T.T., Quang V.M., Campbell J., Chau N.V., Rutherford G.W., Farrar J.J. & Parry C.M.Opportunistic infections in hospitalized HIV-infected adults in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: a cross-sectional study. Int J STD AIDS, 2004, 15, 758–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S.B., Odida M. & Wabinga H.The pathology of severe morbidity and mortality caused by HIV infection in Africa. AIDS, 1991, 5, S143–S148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S.B., Peackock C.S., Hounnou A., Brattegaard K., Koffi K., Hondé M., Andoh J., Bell J. & Cock K.M.Diseases in children infected with HIV in Abidjan Côte d’Ivoire. Br Med J, 1996,312, 335–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche R., Arnoux E., Guérin J.M., Pierre G.D., Laroche A.C., Péan-Guichard C., Elie R., Morisset P.H., Spira T. & Mandeville R.Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome with severe gastrointestinal manifestations in Haiti. Lancet, 1983, 2, 873–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin A.S., Gwanzura L.K.Z., Klein S., Robertson V.J., Musvaire P. & Mason P.R.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in Zimbabwe. Lancet, 1995, 346, 1258–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marins J.R., Jamal L.F., Chen S.Y., Barros M.B., Hudes E.S., Barbosa A.A., Chequer P., Teixeira P.R. & Hearst N.Dramatic improvement in survival among adult Brazilian AIDS patients. AIDS, 2003, 17, 1675–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez Capote R. & Millán Marcelo J.C.Infections and other opportunistic processes in a group of Cuban stage-IV HIV patients. Rev Cubana Med Trop, 1992, 44, 47–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R.F., Lindley A.R., Ambrose H.E., Malin A.S. & Wakefield A.E.Genotypes of Pneumocystis jiroveci isolates obtained in Harare, Zimbabwe, and London United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2003, 47, 3979–3981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R.F., Evans H.E., Copas A.J. & Cassell J.A.Climate and genotypes of Pneumocystis jirovecii. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2007, 13, 445–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohar A., Romo J., Salido F., Jessurun J., Ponce de León S., Reyes E., Volkow P., Larraza O., Peredo M.A. & Cano C.The spectrum of clinical and pathological manifestations of AIDS in a consecutive series of autopsied patients in Mexico. AIDS, 1992, 6, 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A., Lundgren J.D., Masur H., Walzer P.D., Hanson D.L., Frederick T., Huang L., Beard C.B. & Kaplan J.E.Current epidemiology of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis, 2004, 10, 1713–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathoo K.J., Gondo M., Gwanzura L., Mhlanga B.R., Mavetera T. & Mason P.R.Fatal Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV-seropositive infants in Harare, Zimbabwe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2001, 95, 37–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizo M.M., Reviákina V., Navas T., Casanova K., Sáez A., Guevara R.N., Cáceres A.M., Vera R., Sucre C. & Arbona E.Pneumocystosis in Venezuelan patients: epidemiology and diagnosis (2001–2006). Rev Iberoam Micol, 2008, 31 (25), 226–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez E., Toibaro J.J. & Losso M.H.HIV patient hospitalization during the pre and post- HAART era. Medicina (B Aires), 2005, 65, 482–488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Perdomo R., Perez-Cardona C.M. & Suarez-Perez E.L.Epidemiology of pediatric AIDS in Puerto Rico: 1981–1998. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 1999, 13, 651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchenik A.E., Fischl M.A., Dickinson G.M., Becker D.M., Fournier A.M., O’Connell M.T., Colton R.M. & Spira T.J.Opportunistic infections and Kaposi’s sarcoma among Haitians: evidence of a new acquired immunodeficiency state. Ann Intern Med, 1983, 98, 277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisic M., Lattes R., Chapman J.F., Del Carmen Rial M., Guardia O., Seu F., Gutierrez P., Goldberg J. & Casadei D.H.Risk factors for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in kidney transplant recipients: a case-control study. Transpl Infect Dis, 2003, 5, 84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan N., Suchitra J.B., Shet A., Khan Z.K., Martingarcia J., Nonnemacher M.R., Jacobson J.M. & Wigdahl B.Mortality among HIV-Infected patients in resource limited settings: a case controlled analysis of inpatients at a community care center. Am J Infect Dis, 2009, 5, 219–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razón Behar R., Cubero Menéndez O., Vázquez Rios B., Chao Barreiro A., Gala Valiente M. & Cubeñas Chala Y.D.Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Rev Cubana Med Trop, 1977, 29, 103–114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-French A., Suárez M., Cornejo M.X., de-Iglesias M.T. & Roldán T.Pneumocistis carinii pneumonia in patients with AIDS at the Saint Thomas Hospital. Rev Med Panama, 1996, 21, 4–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Vigil E.Neumonía intersticial por Pneumocystis carinii. Rev Cub Ped, 1969, 41, 317 [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini D.D. & Madhi S.A.The high burden of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in African HIV-1-infected children hospitalized for severe pneumonia. AIDS, 2002, 16, 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senya C., Mehta A., Harwell J.I., Pugatch D., Flanigan T. & Mayer K.H.Spectrum of opportunistic infections in hospitalized HIV-infected patients in Phnom Penh Cambodia. Int J STD AIDS, 2003, 14, 411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepkowitz K.A.Opportunistic infections in patients with and patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis, 2002, 34, 1098–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwadda D., Goodgame R., Lucas S. & Kocjan G.Absence of pneumocystosis in Ugandan AIDS patients. AIDS, 1989, 3, 47–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeiro M., Hovnanian A.L., Parra E.R., Canzian M. & Capelozzi V.L.Post-mortem histological pulmonary analysis in patients with HIV/AIDS. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2008, 63, 497–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sritangratanakul S., Nuchprayoon S. & Nuchprayoon I.Pneumocystis pneumonia: un update. J Med Assoc Thai, 2004, 87 (Suppl 2), 309–317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John M.A. & Kumar A.Mortality among HIV-infected paediatric patients in Barbados. West Indian Med J, 2003, 52, 18–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tansuphasawadikul S., Pitisuttithum P., Knauer A.D., Supanaranond W., Kaewkungwal J., Karmacharya B.M. & Chovavanich A.Clinical features, etiology and short term outcomes of interstitial pneumonitis in HIV/AIDS patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, 2005, 36, 1469–1478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhout J.J., Laufer M.K., Perez M.A., Graham S.M., Chimbiya N., Thesing P.C., Alvarez-Martinez M.J., Wilson P.E., Chagomerana M., Zijlstra E.E., Taylor T.E., Plowe C.V. & Meshnick S.R.Pneumocystis pneumonia in HIV-positive adults Malawi. Emerg Infect Dis, 2007, 13, 325–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas S.L., Ponce C.A., Luchsinger V., Silva C., Gallo M., López R., Belletti J., Velozo L., Avila R., Palomino M.A., Benveniste S. & Avendaño L.F.Detection of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis and viruses in presumably immunocompetent infants who died in the hospital or in the community. J Infect Dis, 2005, 191, 122–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vray M., Germani Y., Chan S., Duc N.H., Sar B., Sarr F.D., Bercion R., Rahalison L., Maynard M., L’Her P., Chartier L. & Mayaud C.Clinical features and etiology of pneumonia in acid-fast bacillus sputum smear-negative HIV-infected patients hospitalized in Asia and Africa. AIDS, 2008, 22, 1323–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield A.E., Stewart T.J., Moxon E.R., Marsh K. & Hopkin J.M.Infection with Pneumocystis carinii is prevalent in healthy Gambian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 1990, 84, 800–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A. & Duarte M.I.Respiratory complications in Brazilian patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 1993, 35, 129–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissmann G., Alvarez-Martinez M.J., Meshnick S.R., Dihel A.R. & Prolla J.C.Absence of dihydropteroate synthase mutations in Pneumocystis jirovecii from Brazilian AIDS patients. J Eukaryot Microbiol, 2006, 53, 305–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M.L., Back P., Candy G., Nelson G. & Murray J.Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in African miners at autopsy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2006, 10, 756–760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worodria W., Okot-Nwang M., Yoo S.D. & Aisu T.Causes of lower respiratory infection in HIV-infected Ugandan adults who are sputum AFB smear-negative. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2003, 7, 117–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]