Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRs) regulate cellular processes by modulating gene expression. Although transcriptomic studies have identified numerous miRs differentially expressed in diseased versus normal cells, expression analysis alone cannot distinguish miRs driving a disease phenotype from those merely associated with the disease. To address this limitation, we developed a method (“miR-HTS”) for unbiased high-throughput screening of the miRNome to identify functionally relevant miRs. Herein, we applied miR-HTS to simultaneously analyze the effects of 578 lentivirally transduced human miRs or miR clusters on growth of the IMR90 human lung fibroblast cell line. Growth regulatory miRs were identified by quantitating the representation (i.e. relative abundance) of cells overexpressing each miR over a one month culture of IMR90, using a panel of custom-designed quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assays specific for each transduced miR expression cassette. The miR-HTS identified 4 miRs previously reported to inhibit the growth of human lung-derived cell lines and 55 novel growth-inhibitory miR candidates. 9 of 12 (75%) selected candidate miRs were validated and shown to inhibit IMR90 cell growth. Thus, this novel lentiviral library- and qPCR-based miR-HTS technology provides a sensitive platform for functional screening that is straightforward and relatively inexpensive.

Keywords: microRNA, functional genomics, high-throughput screen, qPCR, tumor suppressors

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression at multiple levels (1-3). MiRs appear to regulate most coding genes and thereby participate in essentially all biological processes including cell survival, proliferation and differentiation (4-6). Consequently, alterations in miR expression and function play pathophysiological roles in cancers and other human diseases (6-8). For example, expression of the miR-34 family is downregulated in various cancers, and has been shown to be directly transactivated by p53, serving as a potent mediator of p53-dependent tumor suppressive mechanisms, including apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and senescence (reviewed in (9)). Delivery of miR-34a mimics inhibited growth of lung cancers with low miR-34a expression in mouse models (10,11). A striking observation in this and other preclinical and clinical studies is the lack of toxicity of miR-based therapeutics to normal cells and tissues, suggesting a large therapeutic window for miR-based therapies (8,12).

Substantial transcriptomic studies have identified many miRs differentially expressed between diseased and normal cells, as well as between different cell lineages and differentiation stages throughout developmental processes (e.g. during hematopoiesis) (6,7,13). However, differential expression of a particular miR does not guarantee a physiological or pathophysiologic role for that miR. Changes in miR expression may be the result of the diseased state rather than the cause, and the function of a miR can be altered without changes in its expression level (e.g. due to context-dependent availability of auxiliary factors required for miR function (14,15)) – such miRs might be excellent biomarkers, but would not be operative therapeutic targets. High-throughput functional screens could distinguish “driver” miRs from “passenger” miRs and thus speed the identification of therapeutically relevant miRs (16).

Unfortunately, current approaches for genome-wide functional/phenotypic screening of the human miRNome require equipment or expertise not readily available in many laboratories and are often prohibitively expensive. Approaches and examples of miR functional screens have been comprehensively reviewed in (16). One approach utilizes transfection of synthetic miR mimic/inhibitor libraries, in which synthetic miRs are arrayed individually in multiple 96- or 384-well plates. Such a miR mimic library approach was used successfully to identify miRs involved in G1 arrest of DGCR8 knockout ES cells (17). Nevertheless, in this approach, screening is limited by (i) the need for cells that can be transfected efficiently and (ii) the use of transient assays, which is disadvantageous since synthetic miRs are diluted with every cell division. These limitations can be overcome by infection of cells with miR overexpression lentivirus (lenti-miR) libraries, with the individual lenti-miRs virus arrayed in 96-well plates. This approach has been used successfully to identify miRs suppressing growth (18) or metastasis (19) of cancer cell lines. The advantage of this format with one miR (mimic, inhibitor, or virus) per well is that the candidate miRs can be attributed very simply to enhance or decrease a specific function. However, arrayed format screens require assays adaptable to microplates and often require robotics to minimize well-to-well variation and other error-prone screening problems. These requirements and associated costs prevent broad application of arrayed miR functional screens.

An alternative screening strategy is to employ pooled lenti-miR or retroviral miR libraries, in which each virus encodes a unique miR or miR cluster (20-25). This screening strategy requires an assay for a phenotype that results from over- or under-representation of cells overexpressing particular miRs. Because these screens simultaneously assay all the miRs in a pool, they depend on downstream methods to distinguish the candidate miRs. Taking advantage of viral integration into the host genomic DNA, the unique miR transgene sequence of each miR virus can serve as the “barcode” for quantitating the number of cells overexpressing a particular miR. Thus, the under- or over-represented barcode allows identification of each miR whose overexpression results in a decrease or increase in the numbers of of cells infected with that particular miR in the functional screen. For example, the barcode of a miR whose overexpression inhibits cell growth would decrease over time; Izumiya et al identified candidate pancreatic cancer suppressive miRs on this basis (22). Conversely, by determining barcodes enriched in migrated cells vs. the starting cell population, candidate miRs that promoted invasiveness of cancer cell lines were identified (23,26). Although these studies successfully employed pooled viral miR libraries in functional screens, their viral miR barcode quantification methods required custom-made microarrays (22,24), bead-based detection systems (20,21) or high-throughput sequencing (23,26). Those approaches require access to costly high-throughput infrastructure and sophisticated informatics analyses, thus restricting the accessibility of these assays.

We report here a simple barcode quantification strategy based on real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) as an effective alternative to the aforementioned identification methods, allowing any laboratory with access to a real-time PCR machine to conduct functional screening of pooled miR libraries. Using a pooled human lenti-miR library and custom-designed qPCR assays to quantify lenti-miR barcodes, we established a novel method (“miR-HTS”) that enables depletion- and enrichment-based functional screening of the human miRNome. As proof-of-principle, we used miR-HTS to screen the IMR90 human lung fibroblast cell line for miRs capable of regulating cell growth. We identified 4 known growth-inhibitory miRs, plus 55 miRs not previously known to regulate growth of IMR90 cells. 9 of 12 (75%) selected candidate miRs were independently validated and confirmed to inhibit IMR90 cell growth, demonstrating the miR-HTS as a straightforward and sensitive alternative to reported approaches.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell culture

The IMR90 cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), and cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, Sacramento, CA, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA), 1x GlutaMAX (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1x penicillin-streptomycin solution (Mediatech).

Design of genomic DNA representation qPCR (GRE-qPCR) assays and the GFP loading control assays

To design GRE-qPCR assays, the miR (plus flanking) insert sequences of each lenti-miR precursor construct were obtained from System Biosciences (SBI, Mountain View, CA, USA) under a mutual non-disclosure agreement between SBI and the University of Maryland Baltimore. GRE-qPCR assays were designed using Primer Express software from Applied Biosystems (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA) or were custom-designed by ABI and purchased. The internal miR-specific forward primers for each GRE-qPCR assay were custom-plated at 0.018 nmole per well in 384-well plates by ABI. The internal common reverse primer, GFP primers, and external common forward and reverse primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The GFP probe and internal common probe were synthesized by ABI. Sequences of all primers and TaqMan probes used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. During the design of GRE-qPCR assays, care was taken to minimize potential non-specific binding of internal miR-specific forward primers to unintended targets (due to sequence similarities between lenti-miRs, e.g. paralogous miRs), by designing primers within the more variable miR flanking sequences. Nevertheless, 6 of the 578 internal miR-specific primers may fail to distinguish paralogous miRs (see “comments” in Supplementary Table 1).

miR-HTS procedure and data analysis

In each miR-HTS, 2.7 million IMR90 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2 with the human Lenti-miR pooled virus library (SBI, Cat# PMIRHPLVA-1) to achieve ~20% transduced cells. 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the infection vehicle (27). On days 3 (t0), 11 (t1), 19 (t2) and 27 (t3) after infection, a fraction of the infected culture (>2 million cells) was harvested and genomic DNA isolated using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The external common forward and reverse primers (Figure 1A) were used to amplify lentiviral integrants; these amplifications used 1.5 μg genomic DNA (per 100 μl PCR reaction) from each time point, 3% DMSO, 0.4 μM external common forward and reverse primers, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1X Phusion HF buffer and 2 units Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). PCR was performed with the following program: 98°C for 2 min, 25 cycles of 98°C for 10 sec, 56.4°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 90 sec, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). 0.2 ng purified PCR products were used as templates for all GRE-qPCR assays; 0.002 ng template was used for the GFP loading control qPCR assay. In addition to the templates, each 20 ul qPCR reaction contained 1X TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (ABI), 900 nM forward and 900 nM reverse qPCR primers, and 250 nM TaqMan probes. qPCR was performed on the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System with the following program: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min. The qPCR results were analyzed using Sequence Detection System software (ABI); see Supplementary Methods for detailed miR-HTS data analysis protocol.

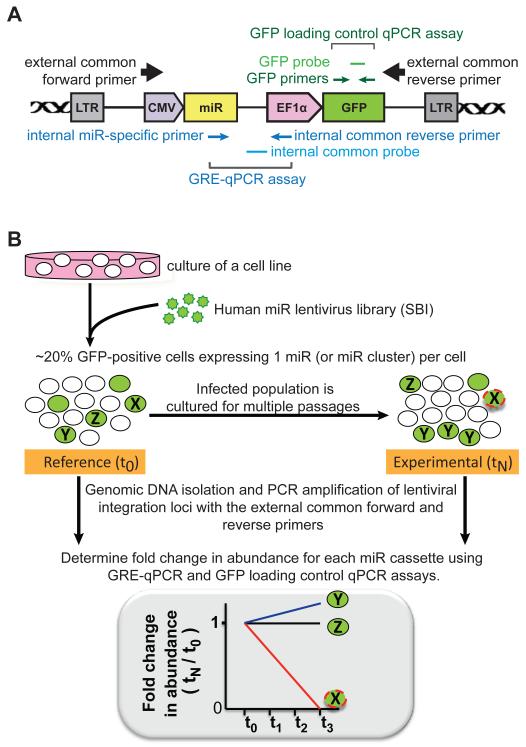

Figure 1.

Design of nested PCR strategy and miR-HTS. (A) Illustration of SBI’s miR lentiviral integrants in the host genome (double helices) between the two viral long terminal repeats (LTRs). Positions of the primers and probes used in this study are depicted relative to the features of lentiviral integrant. CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter; miR, miR cassette; EF1α, human elongation factor 1α promoter; GFP, green fluorescence protein. (B) Experimental design of the miR-HTS conducted in this study. Each green circle is a cell transduced with 1 miR lentivirus. The letter in a green circle denotes the miR being overexpressed in the transduced cell. Open circles represent untransduced cells. Green circle with dashed outline depicts a transduced cell disappearing from the culture (e.g. miR-X). The abundance of miR-infected cells at each time point is determined by GRE-qPCR assays, normalized by GFP loading control qPCR assay, and compared to its starting representation at t0 to calculate fold change in abundance.

Cell growth assay

One day prior to transfection, IMR90 cells were seeded into 96-well plates (3000 cells per well). MiR mimics (5 or 10 nM, Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA) were transfected using 0.15 ul of DharmaFECT2 (Dharmacon) per well in triplicates. On day 5 post-transfection, 10 ul of alamarBlue (Life Technologies) was added to each well and incubated for 4 hours. The alamarBlue fluorescence signal was read on a VictorX3 plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) using 530/578 nm excitation/emission filters.

Caspase activity

Cells were transfected using the same protocol as for the cell growth assay. Caspase activity was measured 4 days post-transfection using the Apo-ONE homogenous caspase 3/7 assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To interrogate the roles of the human miRNome in regulating cellular processes, we developed a functional high-throughput screening (HTS) method that combines a pooled miR overexpression lentiviral (lenti-miR) library with a novel panel of qPCR assays to quantitate each lenti-miR in the library. Lentiviral vectors allow screening in either dividing or quiescent cell types (e.g. stem cells). Infections with the lenti-miR library as a pool make it a scalable screening procedure. In addition, qPCR is widely practiced with standard data analysis protocols, in contrast to more complex data analyses necessary for custom microarray or high-throughput sequencing. The lenti-miR library used in this study contains 578 lentiviruses encoding 539 individual miRs and 39 miR clusters. Each lentivector contains a miR cassette consisting of the native human miR hairpin, plus a stretch of 200-400 bp of genomic flanking sequences to allow for endogenous miR processing. The expression of each miR cassette is controlled by a CMV promoter; an EF1α promoter-driven GFP is located downstream of the miR cassette (Figure 1A). Transduced cells co-express the miR and GFP, allowing flow cytometric quantification of transduced cells.

As a proof-of-concept evaluation of the miR-HTS strategy, we screened for miRs capable of regulating cell “growth” (i.e. proliferation and/or survival) of the IMR90 primary human lung fibroblast cell line (Figure 1B). We chose IMR90 for this proof-of-principle study for 3 reasons. First, miR-34a was already known to potently inhibit IMR90 growth (28), providing a positive control. Second, performing the functional screen in this non-immortalized cell line might generate a more comprehensive set of the human miRs involved in growth than would be obtained using a transformed cell line with deregulated growth control. Third, defective miR processing has been observed in many cancer cell lines (29-31). ~3 million IMR90 cells were transduced with the pooled lenti-miR library at ~20% efficiency (i.e. MOI=0.2) and then cultured for 1 month. This MOI should result in <5% of infected cells containing >1 lentiviral insertion (32), thus avoiding combinatorial effects due to multiple transduced miRs in a single cell (33,34). Infecting 20% of ~3 million cells predicts that each miR lentivirus will integrate into ~1000 cells. Each cell transduced should have an independent genomic integration site (35), reducing the chance of detecting a lentiviral insertion site-specific effect (e.g. host gene disruption). In addition, the many different integration sites for each miR lentivirus should average positional effects on miR expression (e.g. clonal silencing of miR expression) (36).

Identifying the subset of miRs whose overexpression enhanced or reduced cell growth via the miR-HTS requires reliable detection of the changes in representation (i.e. number, abundance or relative frequency) of the cells containing each lenti-miR transgene within the entire transduced population over time in culture. Therefore, we developed a genomic DNA representation qPCR assay (“GRE-qPCR”) to quantify the abundance of cells infected with each lenti-miR by using the unique miR cassette sequence as a barcode. Each GRE-qPCR assay has 3 components (Figure 1A): (i) an internal miR-specific forward primer to identify each miR cassette, (ii) an internal common reverse primer, and (iii) an internal common probe. The internal common reverse primer and probe detect every lenti-miR transgene in the library, but not the endogenous miR locus of the host genome. For high-throughput analysis, each of the 578 different internal miR-specific forward primers for the GRE-qPCR assays was plated in a well of a 384-well plate.

Before conducting the actual miR-HTS, we determined the dynamic range and sensitivity of GRE-qPCR assays, and the amount of genomic DNA required for the GRE-qPCR assay to quantitate cell number accurately. First, 3 cultures of IMR90 cells were separately infected with miR-155, miR-222, or vector-only lentivirus at an MOI=0.2, to mimic the miR-HTS conditions. Specific numbers of miR-155- and miR-222-infected cells were mixed at desired ratios to provide a 4-log range of different cell numbers infected with either of these lenti-miRs (i.e. 10-105 infected cells). As there were 578 different miR cassettes in the library, the expected relative frequency of each specific miR cassette was 1 per 578 transduced cells. To mimic this expected frequency of each miR cassette/barcode in the library and the potential changes in frequency (under- or over-representation) during the 1 month miR-HTS culture, we added vector only-transduced cells at numbers ~20-1800-fold higher than that of lenti-miR virus infected cells (see Table S2 for details of the different cell mixtures prepared). Genomic DNA was extracted from each mixture and subjected to GRE-qPCR assays for miR-155 and miR-222, as well as qPCR assay for GFP (loading control present in every lentiviral integrant). The corrected cycle of threshold (Ct, corrected for template amounts) values of qPCR assays were plotted against the numbers of cells infected with each lenti-miR, in mixtures containing 10-105 cells transduced with the given miR cassette (Figure 2A, B). As expected, we saw a log-linear inverse correlation between the number of infected cells and the correct Ct values. The fitted regression line of the GRE-qPCR assay for miR-155 lost linearity below 50 cells, indicating a detection limit of 50 cells (Figure 2A; regression lines fitted to values with 50-105 cells or 10-105 cells had r2 = 0.94 or 0.84, respectively). The fitted regression line of miR-222 maintained linearity to as low as 10 cells (Figure 2B; regression line fitted to values with 10-105 cells had r2 = 0.98). We determined that 1 or 1.5 μg genomic DNA template per GRE-qPCR assay was required to accurately quantify the numbers of lenti-miR infected cells over a dynamic range of 50-105 infected cells, when 20% of the cell population was transduced in these model experiments.

Figure 2.

Dynamic range of GRE-qPCR assays. (A, B) IMR90 cells separately infected with either miR-155 or miR-222 lentivirus at 20% transduction efficiency were mixed at different ratios as described in the text. Genomic DNA samples were harvested from each mixture and used as templates for each GRE-qPCR assay for either miR-155 (A) or miR-222 (B), to measure the abundance of each lenti-miR barcode. Number of cells infected with either virus (X-axis) was plotted against corrected Ct values (Y-axis; Ct corrected for template amounts). The numbers of cells infected with each virus are labeled above or below each symbol through panels A-D. Regression lines were fitted for cell numbers ≥50 for miR-155 virus infected cells, but for all cell numbers for miR-222 virus infected cells. (C, D) Using the same genomic DNA samples as in panels A and B, the external common forward and reverse primers (illustrated in Figure 1) were used to amplify the miR cassettes from infected cells. Then, purified PCR amplicons were used as templates for each GRE-qPCR assay for either miR-155 (C) or miR-222 (D), to measure the abundance of each lenti-miR barcode. Similar to panels A and B, the number of cells infected with each virus (X-axis, 25-104 cells) was plotted against corrected Ct values (Y-axis). Regression lines were fitted to all cell numbers in panels C and D. (A-D) The r2 value of the fitted regression line is provided at the lower right corner of each panel.

Given that IMR90 yields ~0.002 ng genomic DNA per cell, >250 million IMR90 cells would be needed to produce the 578 μg of genomic DNA needed to perform 578 GRE-qPCR assays (250 million IMR90 cells would require ~62 confluent T175 flasks). To reduce cell number requirements for the miR-HTS, we utilized a nested PCR strategy to produce sufficient DNA from fewer cells. Integrated lentiviral DNA segments containing the miR cassette and GFP transgene were first amplified from genomic DNA samples, using external common forward and reverse primers designed to minimize PCR amplification bias favoring shorter amplicons (Figure 1A). ~70% of the miR cassettes were between 500-600 bp, with the global size range between 182-951 bp (Figure S1A). The external common primers included a total of 1850 bp flanking each miR cassette, which reduced the relative length ratio of the longest to the shortest amplicon from 5.2-fold to 1.4-fold, as compared to the miR cassette alone (Figure S1B). GRE-qPCR assays and GFP loading control qPCR assays were all nested within the amplicon defined by the external common forward and reverse primers (Figure 1A).

After removal of the external common primers to prevent their unwanted further amplification, purified PCR amplicons were used as templates for GRE-qPCR assays to determine the relative abundance of each miR cassette (Figure 1B). Using PCR amplicons (obtained by 25 cycles of amplification of the same initial genomic DNA samples used in Figures 2A, B), GRE-qPCR assays accurately quantified the number of cells infected with either lenti-miR virus, ranging from 25 to 104 cells (Figure 2C, D). The fitted regression line showed a strong log-linear inverse relationship between corrected Ct values and numbers of cells (r2 = 0.99 for either miR-155 or miR-222, with only 0.2 ng PCR amplicon used per GRE-qPCR assay; Figure 2C, D). We could not reproducibly detect a signal when the infected cell number was 10. Similar detection sensitivity and accuracy was observed when either 1.5 or 1 μg genomic DNA was used to generate PCR amplicons, whereas the accuracy and sensitivity in cell number quantification became unreliable when only 0.5 μg genomic DNA sample was used (not shown). We found that 10-30 cycles of PCR amplification generated similar sensitivity and accuracy in cell number quantification (not shown). We opted to use 25 cycles in the miR-HTS to minimize cost; this required only 0.2 ng purified PCR amplicon per GRE-qPCR assay, instead of the 20 ng purified PCR amplicons which would be required using 20 cycles of amplification. The yield of PCR amplicons was ~300ng per 1.5 μg genomic DNA at 25 cycles of amplification, generating more than sufficient templates for all 578 different GRE-qPCR assays. While 1 or 1.5 μg genomic DNA was optimal to maintain accuracy and sensitivity using this nested PCR strategy for IMR90 cells, optimization should be performed as in Figure 2 if the genomic DNA yield per cell of a given cell line is significantly different from that of IMR90.

Once the GRE-qPCR assays were shown to accurately quantify the abundance of lenti-miR-infected cells, we performed the miR-HTS twice in IMR90 cells, as illustrated in Figure 1B. Genomic DNA was harvested from the lenti-miR library-infected cultures at the reference time point (t0, 3 days post-infection, to allow virus integration and GFP expression) and at 3 experimental time points (t1, t2, t3; days 11, 19 and 27 post-infection, respectively, corresponding to every 2 passages; 4-5 population doublings of IMR90 cells per passage). To determine fold changes in abundance of each lenti-miR over time, the abundance of each lenti-miR at each experimental time point was quantified and normalized to its abundance at the reference time point (i.e. tN/t0). Cells overexpressing a miR with no effect on growth would be expected to maintain their starting representation over time (tN/t0=1; e.g. miR-Z). In contrast, cells overexpressing a miR promoting growth should become over-represented (tN/t0>1; e.g. miR-Y), and cells overexpressing a miR inhibiting growth should become under-represented (tN/t0<1; e.g. miR-X).

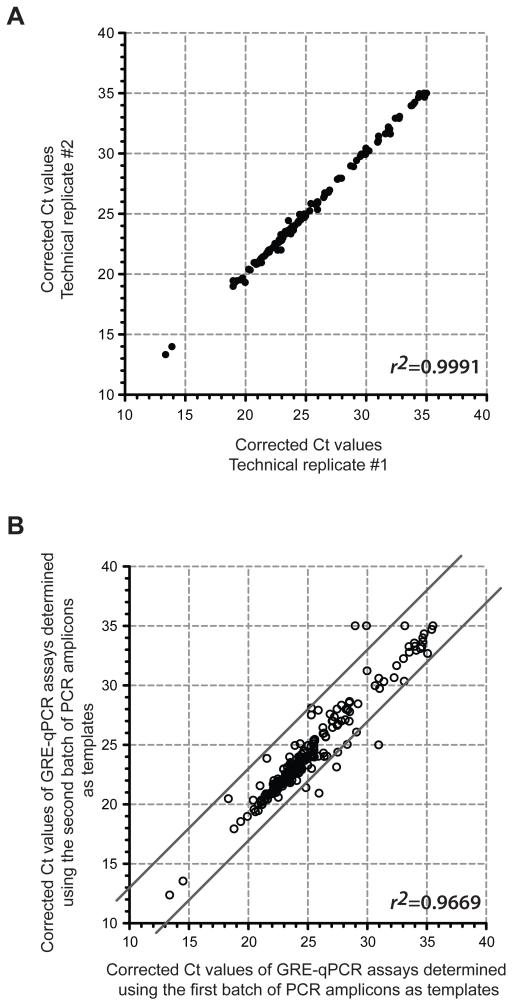

Technical replicates of GRE-qPCR assays were highly reproducible – 2 independent GRE-qPCR assays performed using the same templates (i.e. assaying a single batch of PCR amplicons) were nearly identical (r2~1; Figure 3A). Furthermore, when 2 batches of purified PCR amplicons were generated independently and then each used separately as templates for GRE-qPCR assays, only 4% of the GRE-qPCR assays had differences of ≥3 cycles in corrected Ct (Figure 3B). A 3 cycle difference in corrected Ct (i.e. ΔΔCt=3) is equivalent to a 8-fold change in abundance (37). The 4% frequency of unexpected, ≥8-fold differences observed between the replicates might be explained by the Monte Carlo effect occurring during independent PCR amplifications (38); this further suggested that any observed changes less than 8-fold might due to variations in PCR amplification instead of a true difference in abundance. Therefore, we set our candidate selection threshold at ≥8-fold change from t0; i.e. only miRs that showed a ≥8-fold change in abundance in miR-HTS were considered as growth-inhibitory or growth-promoting candidates (i.e. an 8-fold increase would be tN/t0=8, and an 8-fold decrease would be tN/t0=0.125 in Figure 4, Supplementary Table S4 and Table S3). As we gain additional experience with this assay, we should be able to estimate the variance of the method more precisely, and we may be able to reduce the 8-fold threshold by reducing the Monte Carlo effect, e.g. by pooling multiple independent PCR amplifications prior to the GRE-qPCR.

Figure 3.

Reproducibility of GRE-qPCR assays. (A) The same batch of PCR amplicons (generated using external common primers) was subjected to 304 miR-specific GRE-qPCR assays, in duplicate. The resulting corrected Ct values from each replicate were plotted against each other to examine technical reproducibility of the GRE-qPCR step. Each circle is a different lenti-miR. (B) Two batches of PCR amplicons generated separately were each subjected to 304 GRE-qPCR assays (same assays used in panel A). The resulting corrected Ct values from each batch were plotted against each other to examine the reproducibility of the amplification step using the external common primers. The circles outside of or on the solid lines are GRE-qPCR assays with ≥3 cycles of difference between the 2 batches of templates. The r2 value of fitted regression line (not shown) on the lower right corner of each panel.

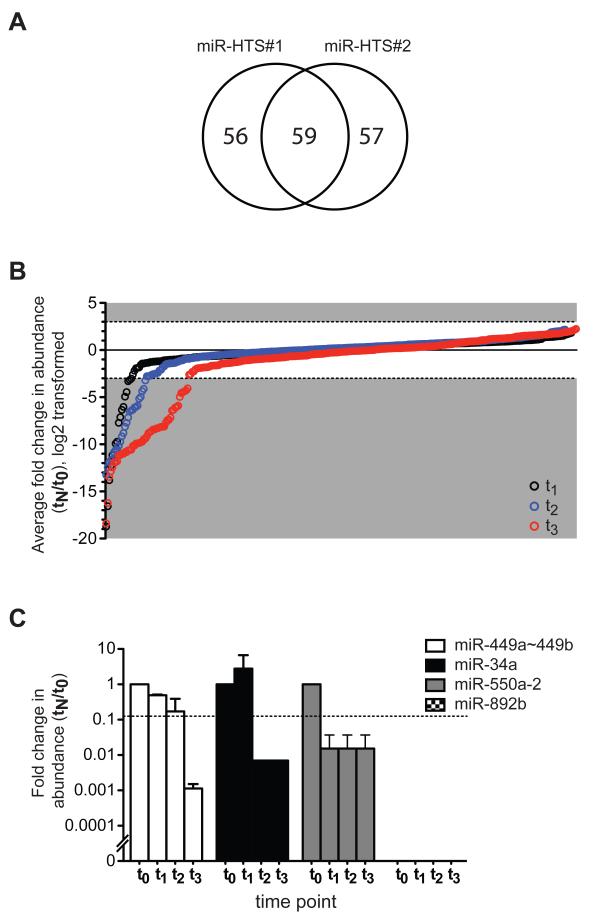

Figure 4.

Results of miR-HTS conducted in IMR90. (A) Venn diagram of all growth-regulatory miR candidates identified from 2 independent miR-HTS replicates, including both growth-inhibitory and growth-promoting candidates. Numbers of candidates identified in the first replicate only (left), the second replicate only (right), and both replicates (middle) were indicated. (B) The average fold changes in abundance of the 2 miR-HTS replicates were log2-transformed, sorted from low to high for each experimental time point. Growth-regulatory miR candidates are located in the shaded area above or below the dashed lines at log2=3 (i.e. tN/t0=8) or log2= -3 (i.e. tN/t0=0.125). For legibility, data are only shown for miR-HTS replicates whose fold changes are consistent in direction. t1, t2, and t3 were days 11, 19 and 27 post-infection, respectively, corresponding to every 2 passages. (C) Example miR candidates of different growth-inhibitory kinetics were summarized from 2 miR-HTS replicates (mean ± SD). The dashed horizontal line marks Y=0.125; equivalent to 8-fold decrease in abundance. MiR-892b illustrated the candidates that were never detected at any time points examined during the miR-HTS in IMR90.

For the two independent miR-HTS experiments, 115 and 116 candidates fulfilled this criterion in the first and second replicate screens, respectively (Figure 4A, 4B). 59 candidates were identified in both miR-HTS replicates – 58 candidate growth-inhibitory individual miRs, and 1 candidate growth-inhibitory miR cluster (see Supplementary Table S4 for the average fold changes of the 2 replicate screens and Supplementary Table S3 for fold changes of each miR-HTS). No growth-promoting miR candidates were reproducibly identified in both miR-HTS replicate screens (Figure 4B). This observation suggested that none of the miRs in the library strongly stimulated IMR90 cell growth under the screening conditions employed, since we detected both under- and over-represented lenti-miRs during initial evaluation of GRE-qPCR assay performance (Figure 2). As expected, miR-34a was among the growth-inhibitory miRs identified. Cells containing the lenti-miR-34a cassette had a ≥8-fold decrease in abundance at both of the last two time points (t2 and t3). At t2, the representation of miR-34a-virus infected cells was 0.7% of that at t0, a >140-fold decrease in abundance (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 4C). We did not observe a further decrease in barcode abundance of miR-34a from t2 to t3, because the GRE-qPCR assay specific for miR-34a did not detect any miR-34a-infected cells at t2 (or at t3). Because the detection limit of a 20 ul qPCR reaction is Ct=35 for detecting a single molecule, qPCR results of Ct>35 were unreliable (39,40). Thus, we assigned Ct=35 when the raw Ct measurements were >35; this allowed us to calculate a minimal fold change when input templates were below our detection limit (as commonly practiced in the literature (41,42)).

We observed different growth-inhibitory kinetics among the 59 growth-inhibitory candidates (Figure 4C, Supplementary Table S4). 26 of the 59 candidates caused ≥8-fold decreased in abundance at that final time point (i.e. candidates with t3/t0 ≤0.125 in Supplementary Table S4), illustrated by miR-449a~449b cluster. 15 of the 59 candidates caused ≥8-fold decreased abundance at both of the last 2 time points (i.e. candidates with t2/t0 and t3/t0 both ≤0.125 in Supplementary Table S4), illustrated by miR-34a. 8 of the 59 candidates caused ≥8-fold decreased abundance at all 3 experimental time points (i.e. candidates with t1,2,3/t0 all ≤0.125 in Supplementary Table S4), illustrated by miR-550a-2. We also identified 10 growth-inhibitory candidates that were undetected at all 4 time points (i.e. candidates with t0,1,2,3/t0=0 in Supplementary Table S4), illustrated by miR-892b. The presence of these 10 lenti-miR viruses in the initial library was verified by infecting REH, a human acute leukemia cell line, using the same lot of lenti-miR library (not shown). Therefore, failure to detect these 10 lenti-miRs in IMR90 cells during miR-HTS was not due to a technical problem with this lentivector or GRE-qPCR assay, because REH cells infected with these 10 lenti-miRs were easily detected at t0 when a miR-HTS was conducted in the REH.

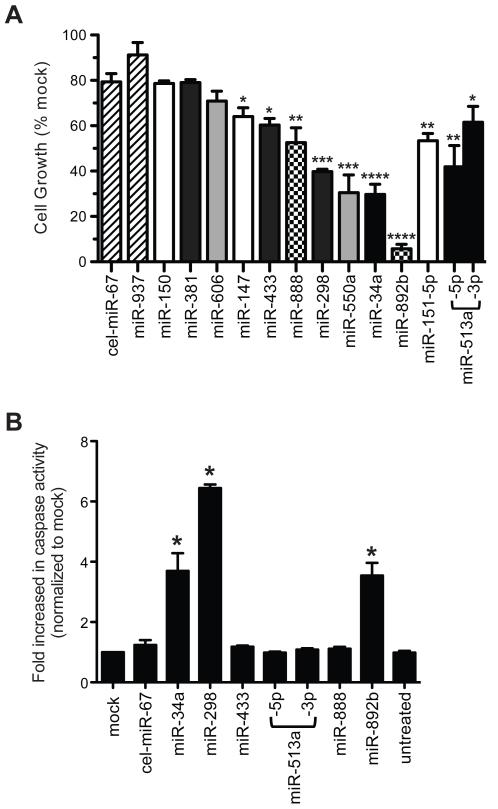

We selected 12 candidate miRs with different growth inhibitory kinetics to test individually for validation. For each selected miR, IMR90 cells were transfected with mature miR mimic, and cell growth was monitored (Figure 5A). C. elegans miR-67 (cel-miR-67), which has minimal sequence homology to any human miR, was used as a negative control. miR-937, which was found not to inhibit IMR90 growth in the miR-HTS assays, provided an additional predicted negative control. 9 of 12 (75%) growth-inhibitory miR candidates tested suppressed IMR90 growth as compared to cel-miR-67 mimic, whereas miR-937 mimic did not affect IMR90 growth (Figure 5A, Supplementary Figure S2). Transient overexpression of candidate miR mimics demonstrated their direct growth-inhibitory capacity, and ruled out the possibility that the effects observed in the miR-HTS were due either to serendipitous mutations that may have arisen during the month-long miR-HTS culture period or due to lentiviral insertional disruption of the host genome. Except for miR-513a, for which we assayed both mature miR strands that could be expressed from a single miR hairpin precursor, we assayed only the mature strand which is currently thought to be expressed predominantly (most mimics used only had one strand commercially available; strand expression data was obtained from miRBase;http://www.mirbase.org/ (43,44)). Interestingly, both miR-513a-5p and miR-513a-3p mimics suppressed IMR90 growth (Figure 5A), suggesting that both strands contributed to the miR-513a-mediated growth inhibition observed in the miR-HTS. Since both mature miR strands are expected to have been overexpressed during the miR-HTS, it remains to be determined whether the mature strand mimics not assayed in this study could suppress IMR90 growth, especially for the 3 tested miRs (i.e. miR-150, -381 and -606) that appeared to be false-positive candidates. Thus, at least 75% (i.e. 9 of 12) of the candidate miRs examined were verified to inhibit IMR90 growth (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 5.

Validation and characterization of selected growth-inhibitory miR candidates. (A) IMR90 cells were transfected with 10 nM miR mimics as indicated. On day 5 post-transfection, cell growth was assessed by the alamarBlue proliferation assay and normalized to the mock (no miR mimic)-transfected sample (i.e. mock as 100%). The cel-miR-67 mimic and miR-937 were negative controls (hatched bars). MiR candidates were plotted using 4 different bar patterns (black, white, gray, checker board) matching respective growth-inhibitory kinetics illustrated in Figure 4C. Mean ± SE are presented for 3 independent experiments. *, p< 0.05; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0005; ****, p<0.0001, each miR mimic versus cel-miR-67. Some of these candidates showed significant growth-inhibition as early as day 3 post-transfection; some showed significant growth-inhibition with 5 nM miR mimics (see Supplementary Figure S2). (B) IMR90 cells were transfected with 10 nM miR mimics. On day 4 post-transfection, caspase-3/7 activity was measured and fold increase in caspase activity was normalized to mock-transfected sample (i.e. mock as 1). Mean ± SE are presented for 3 independent experiments. *, p<0.05, each miR mimic versus cel-miR-67.

For miR-34a, -298 and -892b, we observed cell phenotypes (such as cell retraction and detachment) suggestive of cell death. Therefore, we directly tested the ability of several candidate miRs to induce apoptotic signaling. Indeed, miR-34a, -298 and -892b overexpression activated caspase 3/7 by ~4-7-fold, as compared to the mock transfected control (Figure 5B). The data suggested that these miRs suppress growth in part by inducing apoptotic cell death. The miRs that did not induce caspase activation may instead repress cell proliferation or promote caspase-independent cell death.

This proof-of-principle use of our miR-HTS identified a set of 59 miR candidates that inhibited growth of the IMR90 human fetal lung fibroblast cell line in our functional screen. ~35% of the growth-inhibitory miR candidates identified herein have been implicated previously in growth suppression in IMR90 and/or other lung cancer cell lines, including reports that directly evaluated cellular mechanism experimentally (i.e. cell cycle, apoptosis, senescence assays), and reports that observed expression changes associated with growth-inhibitory function (i.e. upregulated expression in senescent cells versus young cells, or downregulated expression in lung cancer samples versus normal counterpart cells; summarized and referenced in Supplementary Table S4). 15 of these 59 candidate miRs are known to be upregulated in senescent IMR90 cells, including miR-449a/b (45). 10 of these 59 candidate miRs, including 4 upregulated in senescent IMR90 cells, are known to be downregulated in lung cancers, including miR-7 (46). Finally, 4 of the candidate miRs have been shown to promote apoptosis, promote senescence, or inhibit cell cycling in lung cancer cell lines (Supplementary Table S4). It will be interesting to examine whether any of the 11 novel growth-inhibitory miR candidates identified from IMR90 (i.e. the 11 miRs noted with “D” in the column labeled “Known Expression Pattern” of Supplementary Table S4) have tumor suppressive activity in lung cancers that have downregulated expression of these specific miRs.

Intriguingly, the miR-HTS co-identified 3 pairs of candidates that are paralogs encoding the same miR hairpin sequence. Having exactly the same mature miR sequence, these paralogous miRs recognize the same targets and thus would be predicted to have the same effect on cell growth. These paralogous candidates include the miR-550a-1 and miR-550a-2 paralogs (miR-550a-3 was not included in the library used), miR-513a-1 and -513a-2 paralogs, and the miR-128-1 and miR-128-2 paralogs (Supplementary Table S4). In addition, multiple members of 3 additional miR families (i.e. beyond the above 3 sets of paralogs) were identified in the set of growth-inhibitory candidates; e.g. miR-888, -892a and -892b of the miR-743 family (Supplementary Table S4). As a result of the miR hairpin sequence homology within each of these miR families (47), each miR family member may recognize many of the same targets and have similar functions. Moreover, the 59 growth-inhibitory candidates include miR-34a, -34c and the miR-449a~449b cluster, which belong to 2 different miR families, but share identical seed sequence. We were surprised to find that miR-34b, which is also a member of the miR-34 family, was not among the candidates identified by the miR-HTS. Overexpression of miR-34b caused ≥8-fold decrease in abundance at the last time point in only one of the 2 miR-HTS replicate screens.

In summary, we have established the miR-HTS, a novel methodology to conduct unbiased high-throughput miR functional screens. The 75% validation rate among the 12 selected candidates of a proof-of-principle screen in the IMR90 cell line demonstrated the high fidelity of this approach. It should be possible to apply this miR-HTS technology to assess the roles of miRs in cellular processes other than growth-inhibition, targeting any depletion- or enrichment-based phenotype (e.g. one could identify the set of miRs that enhance differentiation using stage/lineage-specific surface markers to enrich the differentiated fraction from the entire cell population). The estimated costs per sample for miR-HTS is less than half of other miR barcode quantification methods (see comparison in Supplementary Table 5). In addition, as the lenti-miR library expands, we can readily add more GRE-qPCR assays. Thus, this novel lenti-miR library- and qPCR-based miR-HTS strategy provides a flexible and reliable platform for miR functional screening, with lower complexity and costs compared to published methods.

Supplementary Material

Author Summary: We introduce a novel functional screening method (“miR-HTS”) for the human microRNA-ome (miRNome) that is high-throughput and sensitive. Using the miR-HTS, we identified 4 known and 55 novel growth-inhibitory microRNA candidates. 75% of the selected candidate microRNAs were validated individually to inhibit cell growth. Using a lentiviral miR library and quantitative PCR, this method provides a sensitive platform for functional screening of the miRNome that is straightforward and cost-effective. We believe the miR-HTS technology will be broadly applied to speed the identification of mechanistically and therapeutically relevant microRNAs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Gerald Vandergrift at Applied Biosystems for expert advice on GRE-qPCR assay designs and development, Dr. Fernando Pineda at Johns Hopkins University for expert advice on statistics, and all Civin lab members for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH/ NCI grant #P01CA70970 to C.C. This paper is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pasquinelli AE. MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:271–282. doi: 10.1038/nrg3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitnis NS, Pytel D, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Pant D, Zheng H, Maas NL, Frederick B, Kushner JA, et al. miR-211 Is a Prosurvival MicroRNA that Regulates chop Expression in a PERK-Dependent Manner. Mol Cell. 2012;48:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benhamed M, Herbig U, Ye T, Dejean A, Bischof O. Senescence is an endogenous trigger for microRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:266–275. doi: 10.1038/ncb2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Garcia I, Miska EA. MicroRNA functions in animal development and human disease. Development. 2005;132:4653–4662. doi: 10.1242/dev.02073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayed D, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:827–887. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:861–874. doi: 10.1038/nrg3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendell JT, Olson EN. MicroRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell. 2012;148:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trang P, Wiggins JF, Daige CL, Cho C, Omotola M, Brown D, Weidhaas JB, Bader AG, Slack FJ. Systemic delivery of tumor suppressor microRNA mimics using a neutral lipid emulsion inhibits lung tumors in mice. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiggins JF, Ruffino L, Kelnar K, Omotola M, Patrawala L, Brown D, Bader AG. Development of a lung cancer therapeutic based on the tumor suppressor microRNA-34. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5923–5930. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bader AG, Brown D, Stoudemire J, Lammers P. Developing therapeutic microRNAs for cancer. Gene Ther. 2011;18:1121–1126. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glorian V, Maillot G, Poles S, Iacovoni JS, Favre G, Vagner S. HuR-dependent loading of miRNA RISC to the mRNA encoding the Ras-related small GTPase RhoB controls its translation during UV-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1692–1701. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serva A, Claas C, Starkuviene V. A Potential of microRNAs for High-Content Screening. J Nucleic Acids 2011. 2011:870903. doi: 10.4061/2011/870903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poell JB, van Haastert RJ, de Gunst T, Schultz IJ, Gommans WM, Verheul M, F Cerisoli, van Noort PI, et al. A Functional Screen Identifies Specific MicroRNAs Capable of Inhibiting Human Melanoma Cell Viability. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Zhang M, Chen H, Dong Z, Ganapathy V, Thangaraju M, Huang S. Ratio of miR-196s to HOXC8 messenger RNA correlates with breast cancer cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7894–7904. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams BD, Guo S, Bai H, Guo Y, Megyola CM, Cheng J, Heydari K, Xiao C, et al. An In Vivo Functional Screen Uncovers miR-150-Mediated Regulation of Hematopoietic Injury Response. Cell Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo S, Bai H, Megyola CM, Halene S, Krause DS, Scadden DT, Lu J. Complex oncogene dependence in microRNA-125a-induced myeloproliferative neoplasms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16636–16641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213196109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izumiya M, Okamoto K, Tsuchiya N, Nakagama H. Functional screening using a microRNA virus library and microarrays: a new high-throughput assay to identify tumor-suppressive microRNAs. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1354–1359. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poell JB, van Haastert RJ, Cerisoli F, Bolijn AS, Timmer LM, Diosdado-Calvo B, Meijer GA, van Puijenbroek AA, et al. Functional microRNA screening using a comprehensive lentiviral human microRNA expression library. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:546. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voorhoeve PM, le Sage C, Schrier M, Gillis AJ, Stoop H, Nagel R, Liu YP, van Duijse J, et al. A genetic screen implicates miRNA-372 and miRNA-373 as oncogenes in testicular germ cell tumors. Cell. 2006;124:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mavrakis KJ, Van Der Meulen J, Wolfe AL, Liu X, Mets E, Taghon T, Khan AA, Setty M, et al. A cooperative microRNA-tumor suppressor gene network in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) Nat Genet. 2011;43:673–678. doi: 10.1038/ng.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Q, Gumireddy K, Schrier M, le Sage C, Nagel R, Nair S, Egan DA, Li A, et al. The microRNAs miR-373 and miR-520c promote tumour invasion and metastasis. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:202–210. doi: 10.1038/ncb1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye Z, Yu X, Cheng L. Lentiviral gene transduction of mouse and human stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;430:243–253. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-182-6_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, Xue W, Zender L, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merritt WM, Lin YG, Han LY, Kamat AA, Spannuth WA, Schmandt R, Urbauer D, Pennacchio LA, et al. Dicer, Drosha, and outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2641–2650. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson JM, Newman M, Parker JS, Morin-Kensicki EM, Wright T, Hammond SM. Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2202–2207. doi: 10.1101/gad.1444406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis-Dusenbery BN, Hata A. MicroRNA in Cancer: The Involvement of Aberrant MicroRNA Biogenesis Regulatory Pathways. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:1100–1114. doi: 10.1177/1947601910396213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM. Fields virology. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blakely K, Ketela T, Moffat J. Pooled lentiviral shRNA screening for functional genomics in mammalian cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;781:161–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-276-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva JM, Marran K, Parker JS, Silva J, Golding M, Schlabach MR, Elledge SJ, Hannon GJ, Chang K. Profiling essential genes in human mammary cells by multiplex RNAi screening. Science. 2008;319:617–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis J. Silencing and variegation of gammaretrovirus and lentivirus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1241–1246. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karrer EE, Lincoln JE, Hogenhout S, Bennett AB, Bostock RM, Martineau B, Lucas WJ, Gilchrist DG, Alexander D. In situ isolation of mRNA from individual plant cells: creation of cell-specific cDNA libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3814–3818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guthrie JL, Seah C, Brown S, Tang P, Jamieson F, Drews SJ. Use of Bordetella pertussis BP3385 to establish a cutoff value for an IS481-targeted real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3798–3799. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01551-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Gelfond JA, McManus LM, Shireman PK. Reproducibility of quantitative RT-PCR array in miRNA expression profiling and comparison with microarray analysis. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caraguel CG, Stryhn H, Gagne N, Dohoo IR, Hammell KL. Selection of a cutoff value for real-time polymerase chain reaction results to fit a diagnostic purpose: analytical and epidemiologic approaches. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23:2–15. doi: 10.1177/104063871102300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji X, Takahashi R, Hiura Y, Hirokawa G, Fukushima Y, Iwai N. Plasma miR-208 as a biomarker of myocardial injury. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1944–1949. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.125310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D152–157. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhahbi JM, Atamna H, Boffelli D, Magis W, Spindler SR, Martin DI. Deep sequencing reveals novel microRNAs and regulation of microRNA expression during cell senescence. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong S, Zheng Y, Jiang P, Liu R, Liu X, Chu Y. MicroRNA-7 inhibits the growth of human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells through targeting BCL-2. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:805–814. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR, Bateman A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D121–124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.