Abstract

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) remains a major cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality in the United States and is actually increasing in certain areas of Europe. Thus, there is a pressing need for new therapies/approaches. Major barriers for reducing morbidity, mortality, and costs of care include: lack of translational animal and human studies of new therapies for AH; limited trials of combination therapies in AH targeted at specific disease mechanisms (e.g., gut permeability, cytokines, oxidative stress); limited studies on non-invasive, non-mortality end points; few studies on mechanisms of steroid non-responsiveness; and inadequate prognostic indicators, to name only a few. In spite of these gaps, we have made major advances in understanding mechanisms for AH and appropriate therapies for AH. This article reviews mechanisms and rationale for use of steroids and pentoxifylline in AH and future directions in therapy.

Keywords: Alcoholic Hepatitis, Steroids, Pentoxifylline, Steroid Resistance

Introduction

Alcoholic Hepatitis (AH) is an important cause of morbidity, mortality, and health care costs in the United States (U.S.) and worldwide. In 2007, 56,809 patients (0.71% of the total) were hospitalized (U.S.) with the ICD-9 diagnosis of AH [1]. Average length of stay (LOS) was 6.5 days, and average hospital costs were $37,769, which is more than twice the cost of myocardial infarction and approximately 4 times the cost of acute pancreatitis.

A nationwide study on AH in Denmark from 1999–2008 was performed [2]. Over that time period the 28-day mortality rose from 12 to 15%, and the 84-day mortality from 14 to 24%. The overall 5-year mortality was 56%; 47% in those without cirrhosis, and 69% in those with cirrhosis. These data from Denmark are quite similar to VA Cooperative Studies data on 4-year mortality: 42% mortality with AH alone, and 65% with AH plus cirrhosis [3]. Thus, in spite of increases in knowledge of mechanisms for AH, mortality is not improving.

Glucocorticoid (prednisone/prednisolone) therapy for AH has been recommended in AASLD and ACG guidelines, but some patients do not respond to steroids and have been termed “steroid resistant”. Research suggests that steroid non-responding AH patients have a 6-month mortality of approximately 60% [7,8]. Pentoxyfilline (weak non-specific PDE inhibitor) has been used in 2 trials in AH with promising results, but further studies on its efficacy/mechanisms of action are needed, as well as studies on more specific PDE inhibitors [4–6].

This article reviews data supporting the use of steroids and pentoxifylline in AH, limitations of both of these drugs, and potential roles for these drugs in selected situations in AH (e.g., response-directed therapy, hepatorenal syndrome).

Steroid Therapy: Mechanisms of action and steroid resistance

Corticosteroids have been successfully used to treat a wide variety of chronic inflammatory diseases and are the current standard of care in the treatment of severe AH. However, glucocorticoid resistance poses a challenging clinical problem. Glucocorticoids (GC) act by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the cytoplasm, which are subsequently activated and translocate to the nucleus. There, the GR can bind to the glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the promoter region of the glucocorticoid responsive genes to switch on the expression of anti-inflammatory genes. Glucocorticoids can also act indirectly to repress the activity of a number of relevant transcription factors, such nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein-1, resulting in the down-regulation of inflammatory genes. Repression of inflammatory genes by GR requires recruitment of co-repressor molecules, particularly histone deacetylases (HDAC-6,-2) [7, 8]. Resistance to the anti-inflammatory effects of GC can be induced by several mechanisms which may differ between patients [9].

Early identification of the subset of patients who are glucocorticoid resistant (usually about 30%) is important to determine treatment strategies. Maddrey, et al. first described factors associated with poor prognosis in AH and devised the original Maddrey Discriminant Function (DF) [10]. Later revised and validated, several trials and meta analyses have consistently shown that patients with a Maddrey’s DF score ≥32 or spontaneous hepatic encephalopathy who are treated with steroids have a statistically significant reduction in mortality compared to placebo [11, 12].

One simple and clinically utilized definition of glucocorticoid resistance in AH patients is the lack of an early change in bilirubin levels (ECBL) at 7 days [13]. The subsequently developed Lille Model also allows patients to receive a seven-day course of corticosteroids and then assesses the responsiveness based on an algorithm combining age, renal insufficiency, albumin, prothrombin time, bilirubin, and evolution of bilirubin at day 7. Patients with a score > 0.45 had a six month survival of 25% and could be discontinued from corticosteroids. However, those patients with scores < 0.45 had an 85% survival and would benefit from continued corticosteroid treatment. The model was based on 295 patients with severe AH with a discriminant function ≥32 or encephalopathy and was subsequently validated prospectively in 118 more patients [14].

Glucocorticoid resistance can be due to multiple molecular mechanisms, not all of which are fully understood. Lowered GR expression and ligand binding are associated with steroid resistance [9]. In alveolar macrophages, a decrease in HDAC2 expression and activity leads to inflammation and the development of steroid resistance [15, 16]. Oxidative and nitrosative stress (seen in AH) can inhibit HDAC2 activity. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a broad-spectrum proinflammatory cytokine that can increase the expression of a number of inflammatory molecules and has been shown to exhibit GC-antagonistic effects in vitro and in vivo. One study in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus found that MIF may play a role in the formation of steroid resistance [17]. Interleukin 2 (IL-2), a key growth factor secreted by T cells, has been found to antagonize the anti-inflammatory response to steroids, and inhibition of IL-2 has been shown to enhance steroid sensitivity in vitro [18]. IL-2 receptor blockade is postulated as a possible therapy to reduce steroid resistance. Lastly, levels of GR-B, an alternatively-spliced form of GR that essentially acts as a dominant negative inhibitor of GC action, is increased in some steroid-resistant disease states [19–21]. Our knowledge of mechanisms of GC action and resistance has been markedly expanded, but further information is still needed to potentially enhance steroid effectiveness in patients who demonstrate early failure to respond.

Impaired steroid responsiveness has also been characterized in inflammatory skin diseases and ulcerative colitis, where it is shown by a reduced maximum inhibitory effect (Imax) of dexamethasone on ex vivo phytohemagglutinin-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation [22]. One study compared 12 patients with severe AH with 12 age- and sex- matched controls. Lymphocyte steroid sensitivity was found to be significantly reduced in the AH group compared with controls (Imax 67[±4.5]% versus 95[±2.3]%, P = 0.0002). In AH survivors, Imax increased in recovery. Steroid responsive patients with an ECBL had a higher mean Imax compared to patients without an ECBL. In the same study, ex vivo treatment of AH lymphocytes with theophylline, which enhances HDAC recruitment, improved steroid responsiveness [23].

Treatment data including infection, HRS

Current class I, level A guidelines from both the American College of Gastroenterologoy and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases advise that patients with severe AH with a Discriminant Function ≥32 without a contraindication to steroids should be considered for a four week course of prednisolone 40mg daily followed by discontinuation or a two week taper. This recommendation is based on the many controlled trials and meta-analyses that have reported the effects of corticosteroids on the treatment of alcoholic liver disease over the past 40 years. The first meta-analysis of corticosteroids as therapy for AH was conducted in 1990. It suggested that corticosteroids reduce short-term mortality in patients with acute AH who have hepatic encephalopathy but do not have active gastrointestinal bleeding. No protective effect was found in patients without hepatic encephalopathy [24].

The most recent Cochrane meta-analysis reviewed 15 trials including 721 patients. Corticosteroids were found to significantly reduce mortality in patients with a DF ≥ 32 or hepatic encephalopathy. No mortality benefit was found in all other patients comparing corticosteroids to placebo or no intervention. Trials were found to be heterogeneous with high risk of bias [12]. To reduce heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was done on individual patient data from five randomized controlled trials. This meta-analysis found that steroids have survival advantage for severe AH with 28 day survival of 79.97% among treated patients compared to 65.7% in patients receiving placebo (P = 0.0005). Patients were divided into groups according to the Lille model: complete responders (Lille score ≤0.16), partial responders (Lille score 0.16–0.56), and null responders (Lille score ≥0.56). Twenty-eight day survival was strongly associated with these groupings (91.1%±2.7% vs 79.4%±3.8% (p=0.02); vs 53.3%±5.1% (p<0.0001)). There was no significant difference in 28-day survival between corticosteroid-treated patients and non-corticosteroid treated patients in the null responder group [11].

Adverse events have been reported in several trials of corticosteroids and can be a limiting factor in therapy. In one meta-analysis, eight trials reporting adverse events were evaluated. The corticosteroid groups had a higher incidence of complications compared to the control groups (16.7% vs 3.8%). The adverse events reported included diabetes mellitus, Cushing’s syndrome, infection, and possible gastric ulcer. However, combining the results of four trials providing data showed that corticosteroids had no significant effect on ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, or development of hepatocellular carcinoma [12]. When pentoxifylline was compared to prenisolone, patients receiving pentoxifylline complained of nausea and vomiting more frequently, but patients receiving prenisolone had more dyspepsia. Recurrent hepatic encephalopathy was the only unique complication in the pentoxifylline group while oral thrush, worsening of ascites, impaired glucose tolerance, delayed wound healing, deep vein thrombosis, and pancreatitis were seen in the prednisolone group. The most important complication in the prednisolone group was the development of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) which occurred in six of 34 patients, all of whom died. None of the patients in the pentoxifylline group developed HRS, which largely accounts for the improved mortality in the pentoxifylline group seen in the study [5].

Infection has classically been viewed as a contraindication to corticosteroids. One prospective study of 246 evaluated using corticosteroid therapy in AH patients with infection. Patients were screened for infection and treated appropriately with antibiotics if infection was found. On admission, 25.6% of patients were found to have an infection and 23.7% developed an infection after treatment with corticosteroids. All patients were treated with prednisolone initially and only responders (identified by the ECBL and Lille model) were continued on it after 7 days. Being a responder to corticosteroids was independently associated with survival (p=0.000001). Infection occurred more frequently in corticosteroid non-responders (P < .000001), but was not independently associated with survival (p=0.52). The authors recommended that screening for infection should occur, but infection should not be a contraindication to corticosteroids. Non-response to steroids was felt to be the key mechanism in development of infection and prediction of survival [25].

If steroid non-responders can be identified, alternative therapy (such as pentoxifylline) could be given. Changing therapy to pentoxifylline in non-responders has been evaluated. All patients were treated with corticosteroids and non-responders were identified using ECBL. Treatment was then changed to pentoxyifylline in non-responders. There was no survival improvement at two months between the group changed to pentoxifylline and non-responders continued on corticosteroids. Therefore, it was concluded that there is no benefit for change to pentoxifylline in non-responders [26].

Combination therapy involving corticosteroids has also been attempted. Since oxidative stress is a strong component of AH, antioxidants such as Vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) have been tried as adjuvant therapy [27]. An open label RCT by Phillips, et al. randomized 101 patients with severe AH to receive prednisone or an antioxidant cocktail over a 4 week treatment period. Mortality at 1 month was lower in the group treated with steroids compared to those given antioxidants (30% vs 46%, P = 0.05). However, mortality was similar at 1 year [28]. A recent study evaluated corticosteroids with NAC in 174 patients. Patients received prednisolone or prednisolone plus NAC. Mortality was improved at one month in the prednisolone-NAC group (p=0.006) but not at three or six months. Deaths due to HRS and infections were less frequent in the prednisolone-NAC group [29].

Combining corticosteroids with pentoxifylline has also been considered. Patients were treated with prednisolone plus pentoxifylline or prednisolone alone. Four week and six month survival was not significantly different between the two groups. Steroid responders, identified by the Lille model, had significantly higher survival rates than non-responders. Thus, combination therapy of corticosteroids plus pentoxifylline had no survival benefit over corticosteroids alone, but steroid non-responders in both groups had lower survival rates, consistent with previous findings [30].

Pentoxifylline: Mechanisms of Action

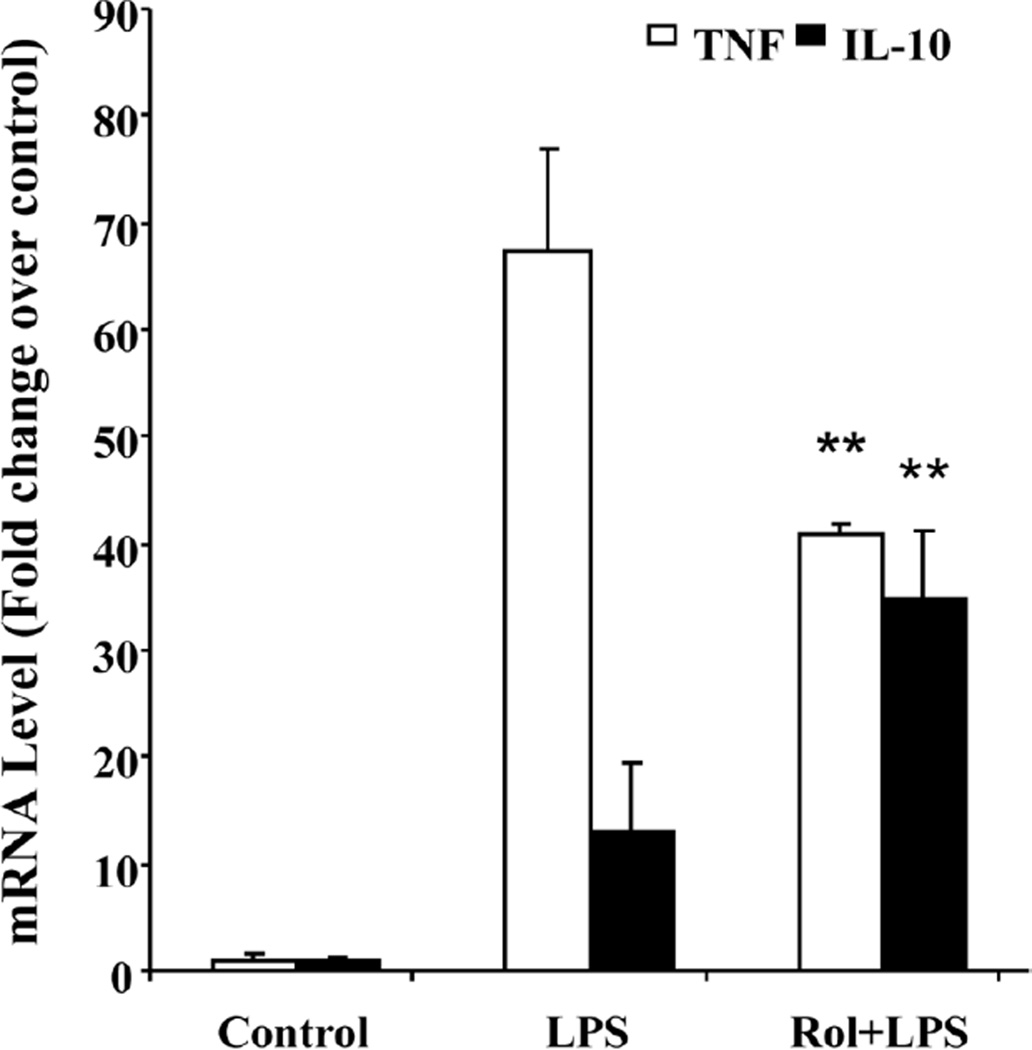

Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (particularly TNF-α and IL-10) play an important role in the pathogenesis of liver injury and the clinical/biochemical abnormalities of AH [31]. Pentoxifylline (PTX) is a nonselective phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor that has been shown to have survival benefit in 2 AH studies [4, 5] and is used by many hepatologists as an alternative to glucocorticoids. PTX treatment increases intracellular concentrations of cAMP and cGMP. Increased cAMP has been shown to positively modulate the cytokine inflammatory response, with a decrease in the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF, and an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of PDE4 inhibition on LPS-stimulated hepatic TNF and IL-10 expression.

PDE4 specific inhibitor, rolipram was administered 4 hours before intraperitoneal LPS injection to Wistar rats. Liver TNF and IL-10 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR. Rolipram significantly decreased LPS-inducible TNF and increased IL-10 expression.

**P<0.01 compared to LPS alone.

Although the critical role of TNF in the progression of ALD is well established, the mechanism(s) by which ethanol enhances TNF expression, particularly in monocytes/macrophages, is still being defined. We have previously shown that chronic ethanol exposure of macrophages resulted in a decline in basal and stimulated cAMP levels, while increasing cellular cAMP levels led to the inhibition of the synergistic enhancement in TNF expression caused by ethanol and LPS. Consistent with our in vitro findings, Kupffer cells obtained from a clinically relevant enteral alcohol feeding model of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) also showed decreased intracellular cAMP levels and increased expression of TNF compared to Kupffer cells from pair-fed rats [32].

Agents that enhance cAMP (such as dbcAMP, adenylcyclase (AC) agonists and PDE4 inhibitors) have been used in vivo studies to protect against LPS- and alcohol-induced hepatitis [33, 34]. cAMP is generated from ATP by AC and is inactivated by cAMP-specific PDEs. Several clinical studies have suggested that AC activity is compromised in alcoholic patients [35, 36]. It was also shown that of 6 different macrophage-specific ACs, AC4, 7 and 9 are suppressed by endotoxin [37]. The critical role of PDE4B in LPS induced TNF expression has been extensively studied by Conti’s laboratory. Using PDE4B-deficient mice, they demonstrated that PDE4B gene activation by LPS is essential for LPS-activated TNF responses and ablation of PDE4B gene protected mice from LPS-induced shock [38]. Importantly, we have shown that chronic ethanol exposure increases LPS-inducible expression of PDE4B in monocytes/macrophages of both human and murine origin, and this is associated with enhanced NFκB activation and transcriptional activity and subsequent priming of monocytes/macrophages leading to enhanced LPS-inducible TNF-α production [39]. We postulate that altered PDE4B and cAMP metabolism cause abnormal TNF and IL-10 production/activity which play a critical role in the development and perpetuation of AH.

Pentoxifylline: Clinical Trials

Clinical trials of patients with AH taking pentoxifylline have shown an improvement in short-term survival and a decrease in complications. In 2000, Akrividis, et al. randomized 101 severe AH patients to receive either pentoxifylline (400 mg orally three times daily) or placebo for 28 days [4]. Twelve of the 49 pentoxifylline patients (24%) died during the study period compared to 24 of 52 control patients (46.1%, p= 0.037). Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) developed in 6 of the pentoxifylline patients and 22 of the control patients who died (50% vs. 91.7%, p=0.009). Two of the 6 pentoxifylline/HRS patients who died had renal impairment at the time of randomization, while the other 4 developed renal failure during the study (8.2%). In contrast, 4 of the control patients who died had renal failure at randomization, and 18 others developed hepatorenal syndrome after randomization (34.6%, p=0.0015).

A 2009 Cochrane review looking at pentoxifylline for AH reviewed the Akrividis 2000 study along with data from 4 smaller studies (reported as abstracts) [40]. While the meta-analysis from the five trials showed that pentoxifylline reduced mortality compared with placebo (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.46–0.89), these results were not supported by trial sequential analysis due to small sample size. This subsequent analysis, as well as concern that the 4 smaller studies had a high risk of bias, led to the conclusion that there was not enough evidence to support the use of pentoxifylline in patients with AH.

Since the Cochrane review, a study by De and colleges randomized 68 severe AH patients to receive either pentoxifylline (400 mg orally three times daily) or prednisolone (40 mg once daily) for the first 4 weeks [5]. After the first 4 weeks, the study was opened. Pentoxifylline patients were continued on the medication for another 8 weeks as tolerated, while prednisolone patients were tapered off their medication by 5 mg per week over a 7 week period.

Mortality significantly improved in the pentoxifylline group, with 5 deaths in 34 patients (14.71%), as compared to the prednisolone group, where 12 of 34 patients died (35.29%, p=0.04). None of the pentoxifylline patients died of hepatorenal syndrome, while 6 of the prednisolone patients died of hepatorenal syndrome (17.6%). Other causes of death included sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and encephalopathy, the frequencies of which were similar between the two groups. The mean MELD score improved more in patients taking pentoxifylline after 4 weeks than in patients taking prednisolone (p=0.04).

A study by Louvet attempted to switch steroid-resistant patients to pentoxifylline after one week of prednisolone. However, no survival benefit was noted after two months [26].

A recent similar trial by Sidhu attempted to analyze the effect of pentoxifylline when added to corticosteroids in an unblinded randomized trial [30]. Thirty-six patients with severe AH were randomized to receive pentoxifylline (400 mg orally 3 times daily) along with prednisolone (40 mg orally once daily) for 28 days, while 34 patients were randomized to receive prednisolone alone. After 28 days, pentoxifylline was stopped and prednisolone was tapered over a two week period. Survival was not significantly different, with 72.2% in the combination group and 73.5% in the corticosteroid group still alive at 28 days. Morbidity between the two groups was also similar including the frequency of septicemia and hepatorenal syndrome. While not statistically significant, the patients who had received pentoxifylline as part of their treatment had less frequent development of hepatorenal syndrome at 6 months (13.9%) compared to those who received prednisolone alone (26.5%, p=0.2385).

A large placebo controlled study of pentoxifylline by Lebrec that enrolled 335 patients with biopsy proven cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class C) [41] evaluated survival. A subset of 133 of these patients also had acute AH: 71 patients in the pentoxifylline arm (400 mg 3 times daily), and 62 patients in the placebo arm. AH patient survival was not statistically significant, with 87.3% and 77.5% of patients in the pentoxifylline group and 85.4% and 71% of patients in the placebo group still alive at 2 and 6 months, respectively (p=0.75 and 0.59). Complication rates for the acute AH subgroup were not presented.

In the analysis of all patients in Lebrec’s study, the percentage of patients without liver-related complications was higher in the pentoxifylline group than in the placebo group at 2 and 6 months (78.6% vs. 63.4% p=0.006 and 66.8% vs. 49.7%, p=0.002, respectively). Bacterial infection was statistically lower at 2 months in the pentoxifylline patients (p=0.03), and the incidence of renal failure was also less in the pentoxifylline group at 6 months (p=0.02). Hepatic encephalopathy was less common in the pentoxifylline group at both 2 and 6 months (p=0.0003 and p=0.001). There was no statistical difference in the rates of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Univariate analysis showed that the only factors predictive of fewer complications in patients were treatment with pentoxifylline and low baseline serum TNF levels.

Since pentoxifylline was observed to reduce the occurrence of hepatorenal syndrome, it was hypothesized that pentoxifylline may prevent hepatorenal syndrome. A recent pilot study by Tyagi’s group in India tested this hypothesis with a randomized, unblinded, placebo controlled trial in patients with cirrhosis and ascites who had normal renal function [42]. The treatment group (pentoxifylline 400 mg orally 3 times daily) consisted of 30 patients, 2 of whom went on to develop hepatorenal syndrome (6.6%) and 1 who died. In the placebo group of 31 patients, 10 developed hepatorenal syndrome (32%, p=0.01) and 3 died. TNF was also found to be significantly higher in patients who developed hepatorenal syndrome compared to those who did not (15.3 vs. 10.9 p=0.01). In contrast to prior studies, this trial had stricter inclusion criteria and excluded patients who reported alcohol intake in the prior six weeks, making it less applicable to AH patients. Nevertheless, the results of this study were encouraging.

Overall, the clinical data suggest that patients with AH who take pentoxifylline have fewer complications and reduced mortality. It appears that a major benefit of pentoxifylline is the prevention of hepatorenal syndrome.

Conclusions

Alcoholic hepatitis is a major cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality in the US and is increasing in parts of Europe. We have made major advances in our understanding of both mechanisms and therapy for this disease process. Specific criteria to determine how severe AH must be to benefit from steroid therapy and predictive scores to evaluate who will respond to steroid therapy have been developed. Thus, we now stop steroids after one week of therapy if the bilirubin is not decreasing. However, we need a much better understanding of mechanisms of steroid responsiveness. Is this due to inherent genetic defects (probably 20% of the normal population is thought to be steroid-non-responsive), changes induced by the inflammatory process in AH, or epigenetic alterations or other causes? We also need to determine whether steroid-non-responsive patients can be converted to steroid responders. Many investigators, including ourselves, believe that patients with severe AH act very similarly to those patients with multi-system organ failure who die of organ failure. Thus, if pentoxifylline or more potent/specific PDE inhibitors attenuate injury to other organs, (e.g., kidney, intestine, lung, etc.), this may improve outcome. We need to better determine mechanisms of action of pentoxifylline and its beneficial effects on other organs, such as kidney, lung, intestine, etc. . We also need to evaluate whether long-term therapy with pentoxifylline, which is a relatively innocuous therapeutic agent, provides benefit including improvement in fibrosis and whether more specific PDE inhibitors are of greater benefit. We are in the fortunate situation of having much better understanding of both of these drugs and appropriate settings in which to utilize these agents. The National Institutes of Health have recently funded three large clinical trials on AH to help us “fine tune” current therapies, as well as develop new therapies, and we eagerly await the results of these important trials..

Footnotes

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1. Liangpunsakul S. Clinical characteristics and mortality of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis patients in the United States. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2011;45(8):714–719. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181fdef1d. * In-hospital mortality rate for AH remains high in the US, especially in those with infectious complications, hepatic encephalopathy, coagulopathy, and acute renal failure. Average length of stay was 6.5 ± 7.y days and average hospital charges were $37,769.

- 2.Sandahl TD, Jepsen P, Thomsen KL, Vilstrup H. Incidence and mortality of alcoholic hepatitis in Denmark 1999–2008: a nation wide population based cohort study. Journal of hepatology. 2011;54(4):760–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chedid A, Mendenhall CL, Gartside P, French SW, Chen T, Rabin L. Prognostic factors in alcoholic liver disease. VA Cooperative Study Group. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1991;86(2):210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1637–1648. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2009;15(13):1613–1619. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gobejishvili L, Crittenden N, McClain C. Controversies in Hepatology: The Experts Analyze Both Sides. Thorofare, NJ.: Slack, Inc.; 2011. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Bosscher K, Haegeman G. Minireview: latest perspectives on antiinflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(3):281–291. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory diseases. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1905–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito K, Chung KF, Adcock IM. Update on glucocorticoid action and resistance. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2006;117(3):522–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL, Jr, Mezey E, White RI., Jr Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75(2):193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mathurin P, O'Grady J, Carithers RL, Phillips M, Louvet A, Mendenhall CL, et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gut. 2011;60(2):255–260. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224097. * Analysis of individual data from five RCTs showed that corticosteroids significantly improve 28-day survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. The survival benefit is mainly observed inpatients classified as responders by the Lille model.

- 12.Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis--a Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2008;27(12):1167–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathurin P, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Carbonell N, Fartoux L, Serfaty L, et al. Early change in bilirubin levels is an important prognostic factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with prednisolone. Hepatology. 2003;38(6):1363–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, Ramond MJ, Diaz E, Fartoux L, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45(6):1348–1354. doi: 10.1002/hep.21607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K, Yamamura S, Essilfie-Quaye S, Cosio B, Ito M, Barnes PJ, et al. Histone deacetylase 2-mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-kappaB suppression. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203(1):7–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito K, Ito M, Elliott WM, Cosio B, Caramori G, Kon OM, et al. Decreased histone deacetylase activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352(19):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang FF, Zhu LA, Zou YQ, Zheng H, Wilson A, Yang CD, et al. New insights into the role and mechanism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in steroid-resistant patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis research & therapy. 2012;14(3):R103. doi: 10.1186/ar3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. di Mambro AJ, Parker R, McCune A, Gordon F, Dayan CM, Collins P. In vitro steroid resistance correlates with outcome in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53(4):1316–1322. doi: 10.1002/hep.24159. *Clinical outcome of steroid therapy in an AH patient cohort correlated with in vitro steroid resistance and IL-2 blockade improved in vitro steroid sensitivity. Thus, intrinsic lack of steroid sensitivity may contribute to poor clinical response to steroids in severe AH and IL-2 receptor blocade may represent a possible intervention.

- 19. Barnes PJ. Mechanisms and resistance in glucocorticoid control of inflammation. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2010;120(2–3):76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.018. *Excellent review of mechanisms and resistance in glucocorticoid control of inflammation. New concepts in resistance including epigenetics are covered.

- 20.Rajendrasozhan S, Yang SR, Edirisinghe I, Yao H, Adenuga D, Rahman I. Deacetylases and NF-kappaB in redox regulation of cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation: epigenetics in pathogenesis of COPD. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2008;10(4):799–811. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogatsky I, Ivashkiv LB. Glucocorticoid modulation of cytokine signaling. Tissue antigens. 2006;68(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hearing SD, Norman M, Probert CS, Haslam N, Dayan CM. Predicting therapeutic outcome in severe ulcerative colitis by measuring in vitro steroid sensitivity of proliferating peripheral blood lymphocytes. Gut. 1999;45(3):382–388. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendrick SF, Henderson E, Palmer J, Jones DE, Day CP. Theophylline improves steroid sensitivity in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;52(1):126–131. doi: 10.1002/hep.23666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imperiale TF, McCullough AJ. Do corticosteroids reduce mortality from alcoholic hepatitis? A meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Annals of internal medicine. 1990;113(4):299–307. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, Dharancy S, Hollebecque A, Canva-Delcambre V, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):541–548. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, Coevoet H, Texier F, Thevenot T, et al. Early switch to pentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. Journal of hepatology. 2008;48(3):465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.010. [pii] 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loguercio C, Federico A. Oxidative stress in viral and alcoholic hepatitis. Free radical biology & medicine. 2003;34(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips M, Curtis H, Portmann B, Donaldson N, Bomford A, O'Grady J. Antioxidants versus corticosteroids in the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis--a randomised clinical trial. Journal of hepatology. 2006;44(4):784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen-Khac E, Thevenot T, Piquet MA, Benferhat S, Goria O, Chatelain D, et al. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(19):1781–1789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Singla P, Gupta D, Sood A, Chhina RS, et al. Corticosteroid plus pentoxifylline is not better than corticosteroid alone for improving survival in severe alcoholic hepatitis (COPE trial) Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(6):1664–1671. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2097-4. *This relatively small study (70 subjects) compared the efficacy of corticosteroids plus pentoxifylline with that of corticosteroids alone in improving survival of severe AH patients. Somewhat surprisingly, combination therapy showed no significant survival advantage, and results of larger trials are awaited.

- 31.McClain CJ, Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1989;9(3):349–351. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gobejishvili L, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S, Uriarte S, Song Z, McClain C. Chronic ethanol-mediated decrease in cAMP primes macrophages to enhanced LPS-inducible NF-kappaB activity and TNF expression: relevance to alcoholic liver disease. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2006;291(4):G681–G688. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00098.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taguchi I, Oka K, Kitamura K, Sugiura M, Oku A, Matsumoto M. Protection by a cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor, rolipram, and dibutyryl cyclic AMP against Propionibacterium acnes and lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse hepatitis. Inflammation research : official journal of the European Histamine Research Society [et al] 1999;48(7):380–385. doi: 10.1007/s000110050475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gouillon ZQ, Miyamoto K, Donohue TM, Wan YJ, French BA, Nagao Y, et al. Role of CYP2E1 in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease: modifications by cAMP and ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 1999;4:A16–A25. doi: 10.2741/gouillon. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diamond I, Wrubel B, Estrin W, Gordon A. Basal and adenosine receptor-stimulated levels of cAMP are reduced in lymphocytes from alcoholic patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84(5):1413–1416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagy LE, Diamond I, Gordon A. Cultured lymphocytes from alcoholic subjects have altered cAMP signal transduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(18):6973–6976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risoe PK, Wang Y, Stuestol JF, Aasen AO, Wang JE, Dahle MK. Lipopolysaccharide attenuates mRNA levels of several adenylyl cyclase isoforms in vivo. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1772(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin SL, Lan L, Zoudilova M, Conti M. Specific role of phosphodiesterase 4B in lipopolysaccharide-induced signaling in mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1523–1531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gobejishvili L, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S, McClain C. Enhanced PDE4B expression augments LPS-inducible TNF expression in ethanol-primed monocytes: relevance to alcoholic liver disease. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2008;295(4):G718–G724. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90232.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitfield K, Rambaldi A, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007339.pub2. CD007339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lebrec D, Thabut D, Oberti F, Perarnau JM, Condat B, Barraud H, et al. Pentoxifylline does not decrease short-term mortality but does reduce complications in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5):1755–1762. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.040. [pii] 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tyagi P, Sharma P, Sharma BC, Puri AS, Kumar A, Sarin SK. Prevention of hepatorenal syndrome in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: a pilot randomized control trial between pentoxifylline and placebo. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(3):210–217. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283435d76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]