Abstract

Disclosure of the HIV status to infected children is often delayed due to psychosocial problems in their families. We aimed at improving the quality of life in families of HIV-infected children, thus promoting disclosure of the HIV status to children by parents. Parents of 17 HIV-infected children (4.2–18 years) followed at our Center for pediatric HIV, unaware of their HIV status, were randomly assigned to the intervention group (8 monthly sessions of family group psychotherapy, FGP) or to the control group not receiving psychotherapy. Changes in the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB-I) and in the Short-Form State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Sf-STAI), as well as the HIV status disclosure to children by parents, were measured. Ten parents were assigned to the FGP group, while 7 parents to the controls. Psychological well-being increased in 70% of the FGP parents and none of the control group (p=0.017), while anxiety decreased in the FGP group but not in controls (60% vs. 0%, p=0.03). HIV disclosure took place for 6/10 children of the intervention group and for 1/7 of controls. Family group psychotherapy had a positive impact on the environment of HIV-infected children, promoting psychological well-being and the disclosure of the HIV status to children.

Introduction

Positive mental health encompasses diverse aspects related to quality of life and general well-being, and can be considered as the achievement of emotional resilience.1 Resilience is the psychological process developed in response to intense life stressors that facilitates healthy functioning, playing a major role in response to illness and other life adversities.2 The needs of children living with HIV infection are progressively shifting from those strictly clinical to those related to psychosocial issues.3 However, this is in contrast to the established model of care of HIV-infected children, which is characterized by a close physician–patient relationship. Such a model is largely the consequence of the social stigma with the need of hiding the disease. However, this often results in delayed disclosure to children and adolescents.4,5

Our Unit has been providing care to children, adolescents, and young adults with HIV infection since the onset of AIDS epidemics, in agreement with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.6 In parallel with the evolving aspects of HIV epidemics, we progressively developed a comprehensive approach integrating psychological, social, and biomedical support for the management of HIV. This model provides in- and outpatient care by the medical staff of the reference center, and it also includes home care provided by physicians and nurses working in the hospital.

Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), a specific instrument to evaluate the disabilities and dysfunctions in children, we showed that environmental factors and psychosocial issues had a major negative impact on the quality of life of HIV infected children and their families.7 Interestingly, the greatest impairment reported by parents was related to the need of hiding the HIV infection status to their children because of social stigma. This was associated with delayed disclosure,7 which in turn generated a vicious cycle of increased anxiety, ultimately leading to further functional disabilities in HIV-infected children. Therefore, disclosure has a key role in coping with HIV infection. Current recommendations regarding the disclosure of HIV infection to children are based on lessons learned from pediatric oncology.8 Similar to trends observed in oncology, many parents and care providers of HIV-infected children thought they need to protect children from emotional burdens and social prejudices associated with their disease. With the advent of new therapies in the mid 1990s, and the dramatic improvements in the mortality and morbidity of HIV-infected children, changes in disclosure practices began to take place, and the disclosure of HIV infection is now a step of care.5 Disclosure is not only related to psychosocial aspects and eventually resilience, rather it also affects therapy and its outcome.

In a recent qualitative study, caregivers reported that their children became more adherent to antiretroviral medications following disclosure.9 In an interview involving 120 families in a resource-limited setting, disclosure was perceived as a step towards self-sufficiency, but also with potential negative social effects.10 On the contrary, other studies have indicated that children aware of their HIV status may be less likely to adhere.11 The conflicting relationship between disclosure and adherence may be explained by the age-related patterns of relationship between the child's age, the type of communication, and the support to it. Children and adolescents frequently perceive limited communication before, during, and after disclosure, which is a discrete event rather than a process.12 Once children are made aware of their HIV status, their caregivers expect them to become able to self-manage treatment, without supervision and reminding.13 However, we previously showed that adherence was strongly related to caregivers more than any other factor, such as child's age or disease status.12 Disclosure is therefore an important step that has a broad effect on the HIV infection course and needs to be accompanied by psychological support.

These issues led us to plan a family group psychotherapy (FGP) with the families of children with HIV infection, with the aim of removing barriers that prevent disclosure, and ultimately to increase resilience in the caregivers. The basic concept was to work with small groups of caregivers and to discuss common problems and feelings in order to build competence and self-reliance in families and patients, so that parents and their children could effectively manage their own health.

The intervention was incorporated in our HIV care planning. Specific objectives of the intervention were the following: to provide information for sound management of the disease; to offer an empathetic understanding of the problems and to discuss problems and solutions; and to focus on HIV disclosure in a timely and appropriate manner, acknowledging the need for a close interaction between parents of children, the medical staff and the team of psychologists.

Methods

Children and adolescents with HIV and their families, seen at our HIV reference center for the management of pediatric HIV infection, were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were the following: age 1–18 years; diagnosis of vertical HIV infection obtained>1 year before enrollment; unawareness of HIV infection status; therapy according to the criteria reported in the NIH guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection.6 To estimate adherence quantitatively, each caregiver was asked how many doses of the total prescribed antiretroviral therapy had been omitted in the previous 4 days, and children were defined as non-adherent if they had taken <95% of all prescribed doses of antiretroviral therapy in this period. This method provides a reliable estimate of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in children.14 Patients and caregivers were randomly assigned to either FGP intervention or control group. Parents decided whether the mother, the father, or the caregiver would participate in the support group. Written informed consent was obtained for every participant.

The intervention was structured through meetings between parents of children and the team of psychologists of the reference center. Eight 2-h group sessions took place once a month. The first and last meetings were longer to allow test administration. The content of the meetings is described in the Appendix. Families in the control group received complete health assistance but no psychological support and they were not aware of the intervention.

The following tests were administered before and after the support group meetings:

The Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB-I)15 that assesses the psychological and mental health status of an individual through 22 items. The scale consists of six domains: anxiety, depression, sense of positive and well-being, self-control, general health, and vitality. The overall score ranges from 0 to 110 (worst–best states possible). Scores 91–110 are consistent with high level of well-being; scores 71–90 with good level of well-being; scores 51–70 with medium level of well-being; scores 31–50 with low level of well-being; scores 0–30 with very low level of well-being.16 Changes in psychological well-being index were defined according to these ranges.

The Short-Form State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Sf- STAI)17 is a six-item version of the Spielberger STAI for the assessment of anxiety state.18 It is a validated instrument for measuring anxiety in adults. It clearly distinguishes between a temporary condition of anxiety in a specific situation and anxiety as a general trait. The results of the scale range from 20 to 80. A score≥60 indicates an elevated level of anxiety; a score between 50–59 indicates a moderate level of anxiety; a score≤49 indicates absence of anxiety.17 Changes in anxiety were defined according to these ranges. A final self-assessment through rating was obtained after the last meeting.

Both PGWB-I and Sf-STAI have proven reliable in chronic conditions, with a high test/retest coefficient.19,20

Results were expressed as number/percent or as mean±SD. The Student t-test, the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, and the χ2 method, or exact Fisher's test when appropriate, were performed to compare the variables and p<0.05 was the cut-off for significance. Data were analyzed with the SPSS package version 20.

Results

A total of 17 parents of as many children (mean age, 11.7±3.7 years; range, 4.2–18.0; 7 boys) were enrolled, 13 of them being biological and 4 foster parents. Ten children were single orphans, 1 was a double orphan and entrusted to a caregiver; 10 children were of Italian origin and 7 were of non-EU origin. Ten caregivers were randomly assigned to support group intervention and the other 7 to controls. The corresponding children populations were age-matched (Table 1). The intervention group had a higher viral load, due to the presence of 3 patients with>100 copies/ml. However, all patients had<1000 viral copies/ml. Of note, viral load was reduced in 2 children following the intervention (in 1 patient the viral load was associated with poor compliance, and in another with viral resistance).

Table 1.

Baseline Psychological Outcomes and Socioeconomic Features of Patients and Families of Family Group Psychotherapy Group (Intervention) and Control Group

| Intervention (n=10) | Controls (n=7) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| F | 5 (50) | 5 (71) | 0.622 |

| M | 5 (50) | 2 (29) | |

| Family, n (%) | |||

| Natural | 7 (70) | 6 (86) | 0.603 |

| Adoptive | 3 (30) | 1 (14) | |

| Age mean±SD | 12±4 | 11±2 | 0.114 |

| Orphanity, n (%) | |||

| One | 5 (50) | 5 (71) | 0.784 |

| Both | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| None | 4 (40) | 2 (29) | |

| Origin, n (%) | |||

| Italian | 5 (50) | 5 (71) | 0.622 |

| Extra EU | 5 (50) | 2 (29) | |

| CG education, n (%) | |||

| Middle school or less | 4 (40) | 6 (86) | 0.134 |

| High school | 5 (50) | 1 (14) | |

| Graduation | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Income, n (%) | |||

| One | 6 (60) | 4 (57) | 0.59 |

| Both | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| None | 4 (40) | 2 (29) | |

| Mother transmission, n (%) | |||

| Sex | 3 (30) | 5 (72) | 0.486 |

| Blood transfusion | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Drug | 2 (20) | 1 (14) | |

| Adoptive | 3 (30) | 1 (14) | |

| Adherence to HAART, n (%) | |||

| Adherent | 6 (60) | 5 (71) | 0.627 |

| Non-adherent | 4 (40) | 2 (29) | |

| CD4 lymphocytes/μL mean±SD | 795±415 | 604±233 | 0.124 |

| HIV RNA copies/mL mean±SD | 92±117 | 20±0.7 | 0.001 |

HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Psychological well-being

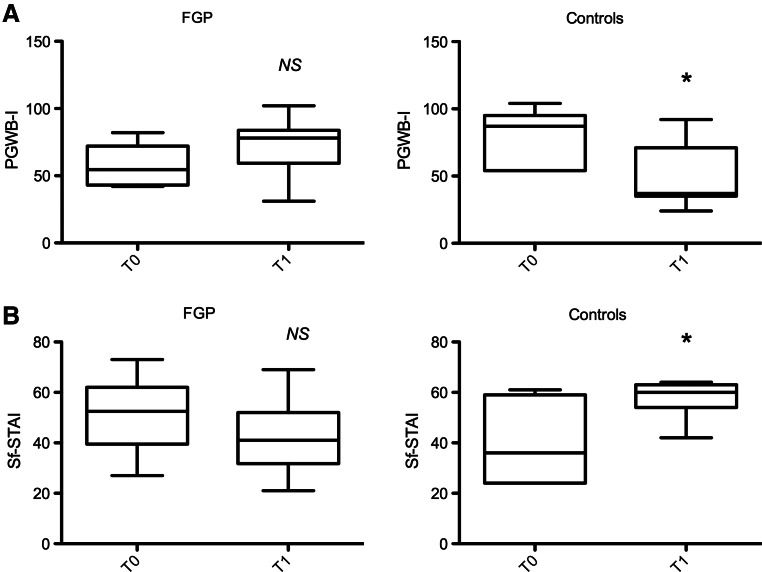

Baseline PGWB-I scores differed between FGP and controls (57.4±15 vs. 79.7±7.3, p=0.04). The average PGWB-I increased in the intervention group (T0: 57.4±15; T1: 72.5±21, p=0.22), and decreased in controls (T0: 79.7±7.3; T1: 48.1±9, p=0.01) (Fig 1A). Psychological well-being improved in 70% of the caregivers in the FGP group versus none of the control group; it decreased in 20% of FGP parents versus 71% of the controls (p=0.01), and finally remained stable in 10% and 29% of the FGP and controls, respectively (Table 2). An association was observed between parental schooling and changes in parental well-being (p=0.02) but not with other social and economic factors (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Psychological general well-being (A) and anxiety (B) scores before and after family group psychotherapy. FGP, family group psychotherapy; PGWB-I, Psychological General Well-Being Index; Sf-STAI, Short form of State-Trait Anxiety Index; *p<0.05.

Table 2.

Changes in Psychological and Clinical Features After the Family Group Psychotherapy

| Intervention (n=10) | Controls (n=7) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CG PGWB-I n (%) | |||

| Improved | 7 (70) | 0 (0) | 0.017 |

| Stable | 1 (10) | 2 (29) | |

| Worsened | 2 (20) | 5 (71) | |

| CG Sf-STAI n (%) | |||

| Improved | 6 (60) | 0 (0) | 0.037 |

| Stable | 2 (20) | 2 (29) | |

| Worsened | 2 (20) | 5 (71) | |

| HIV disclosure n (%) | |||

| Yes | 6 (60) | 1 (14) | 0.134 |

| No | 4 (40) | 6 (86) | |

| Change in adherence to HAART n (%) | |||

| Improved | 3 (30) | 2 (29) | 0.784 |

| Stable | 5 (50) | 5 (71) | |

| Worsened | 2 (20) | 0 | |

| Adherence to HAART T1 n (%) | |||

| Adherent | 7 (60) | 7 (71) | 0.228 |

| Non-adherent | 3 (40) | 0 (29) | |

| CD4 lymphocytes/uL T1 mean±SD | 863±379 | 665±271 | 0.677 |

| HIV RNA copies/ml T1 mean±SD | 92±150 | 20±1 | 0.06 |

CG, caregiver; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; PGWB-I, Psychological General Well-Being Index; Sf-STAI, Short form of State-Trait Anxiety Index; T1, after the intervention.

Table 3.

Change in Psychological General Well-Being and Anxiety of Caregivers After the Intervention According to Parental Schooling

| CG education (n) | Middle or less (10) | High (6) | Grad (1) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGWB-I n (%) | ||||

| Improved | 2 (20) | 4 (67) | 1 (100) | 0.021 |

| Stable | 1 (10) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| Worsened | 7 (70) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Sf-STAI n (%) | ||||

| Improved | 2 (20) | 4 (67) | 0 (0) | 0.013 |

| Stable | 1 (10) | 2 (33) | 1 (100) | |

| Worsened | 7 (70) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

CG, caregiver; PGWB-I, Psychological General Well-Being Index; Sf-STAI, Short form of State-Trait Anxiety Index.

Anxiety

The baseline Sf-STAI scores were not different between FGP and controls. The average Sf-STAI decreased in the intervention group (T0: 51.7±4; T1: 43±4, p=0.22), while it increased in controls (T0: 40.6±6; T1: 57.±3, p=0.01) (Fig 1B). Anxiety was significantly diminished in 60% of caregivers in the intervention group versus none of the controls (p=0.03) (Table 2). Similarly to PGWB-I, changes in anxiety were also associated with parents' education (p=0.01) (Table 3).

Disclosure of HIV infection to children and adherence to antiretroviral therapy

Disclosure took place in six of 10 (60%) of the group support caregivers within 12 months following the intervention. Comparatively only 1 of 7 (14%) of controls achieved this step (p=0.59). However, disclosure was correlated neither with PGWB-I (p=0.15) nor with Sf-STAI (p=0.45), nor with any other social, cultural, or economic features (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rate of Disclosure of HIV Status to Children by Families According to Psychological Outcomes of the Intervention

| HIV disclosure (n) | Yes (7) | No (10) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGWB-I n (%) | |||

| Improved | 5 (71) | 2 (20) | 0.156 |

| Stable | 0 (0) | 3 (30) | |

| Worsened | 2 (29) | 5 (50) | |

| Sf-STAI n (%) | |||

| Improved | 4 (57) | 2 (20) | 0.456 |

| Stable | 1 (14) | 3 (30) | |

| Worsened | 2 (29) | 5 (50) | |

PGWB-I, Psychological General Well-Being Index; Sf-STAI, Short form of State-Trait Anxiety Index.

Changes in adherence to HAART of children were not correlated to intervention (Table 2) nor to the disclosure of the HIV status to children by parents.

Assessment of the perceived benefit and efficacy of the intervention

A final self-assessment of the benefits perceived from the intervention was obtained after completing all sessions at the last group meeting: caregivers answered the question ‘To what extent did the group help you understanding issues concerning HIV?’, and the level was 7.1±2 on a score 0–9 (not helpful–very helpful). A final self-assessment of the empathetic support received was provided by caregivers answering the questions ‘How helpful was it to meet other parents of children with HIV?’ and ‘To what extent did attending the group help you in feeling less isolated with regard to your child's HIV infection?’. On a score 0–9 (not helpful–very helpful), the perceived helpfulness by empathetic support was 9±0 and 9±0, respectively. Only one meeting was missed by two participants.

Discussion

Our results show that an intervention based on group psychotherapy delivered to families of HIV-infected children improves the quality of life, increases their general well-being, and reduces their anxiety state, thereby increasing their resilience. Our observations, even with the limitation of a wide age range of the patients and of the heterogeneity of the type of families, show that the support group effectively breaks the isolation and creates opportunities for carers, by sharing psychological resources and experiences. These results also depend on parents' education, as suggested by the significant association between carers' schooling and their psychological improvement in terms of both general well-being and anxiety. It is well known that the education strongly affects the capacity of living with chronic diseases and that supportive interventions are more effective in high culture settings. This is demonstrated for diseases such as diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: positive effects on depression, health-related quality of life, feelings of mastery, and self-efficacy are confined to patients with high education, while those with only a primary education do not benefit from supportive interventions.21 Our data obtained in a small population of families of low educational level indicate that interventions tailored to those specific conditions, with simple peer communication are effective and contribute to resilience.

Although there are limited data on psychological support groups in pediatric settings, interventions involving families of children with HIV are generally delivered with the aim of improving patients' care beyond strictly clinical aspects. However, the effects of interventions are rarely measured. We did that and also applied disclosure as a secondary outcome parameter of the intervention. The latter promoted the disclosure of HIV status from carers to children. However, the relationship between psychological support and disclosure process by the caregivers is complex, and this effect could be related to cognitive gain rather than to psychological effect. Moreover, not all the studies clearly showed an impact of the disclosure on quality of life, as well as the acceptance of disclosure appears to be higher in foster parents.22,23 We did not find any association between disclosure and type of parents (biological vs. foster), but this might be due to the heterogeneity of our populations. The group therapy fostered the information about HIV infection in carers, enabling them to disclose to their children a troublesome truth. Awareness is a prerequisite to self care and it is a fundamental leading force in the construction of personal future.24 Current recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics support disclosure to children as young as 8 years of age and to all adolescents.25 From this perspective, the support by the group provided important motivations to self-management and resilience.

Looking at clinical features, our population was largely made of children and adolescents with virologically and immunologically well-controlled disease, reflecting the high standards of clinical care in pediatric HIV. No association was found between either HIV viral load or number of CD4+ lymphocytes and primary or secondary outcomes of our intervention, and only three patients had detectable viral load at baseline.

Unawareness and psychological discomfort could affect adherence and hamper effective management of the disease, especially in adolescents, in whom the lack of responsibility prevents an effective therapeutic alliance. We previously described a changing pattern of adherence over time in HIV-infected children and adolescents, and demonstrated that psychosocial features of caregivers and children play a major role in adherence. Interestingly, children of foster parents had the highest level of adherence and it may be expected that depressed and debilitated parents have limited ability in sustain optimal adherence in their HIV-infected children.14 However, adherence is the result of a complex interplays of determinants and it is impossible to establish a direct link with psychotherapeutic interventions. In our sample, only 65% of all children showed an optimal adherence to HAART at baseline. We observed that adherence increased over the period of observation. However, this was also the likely consequence of the higher attention paid by physicians and other health care professionals to this outcome during the study. In contrast with the physical well-being, psychological discomfort was high in the families enrolled, and the support group was well accepted and recognized as effective by families. The mutual empathetic support among the participants was perceived as very helpful. These interventions should be integral part of the standard care for HIV-infected children and adolescents. Psychosocial issues in young patients should be carefully considered to ensure clinical success.26 Management of psychological impairment through a biopsychosocial model of care may reduce anxiety, depression, and social isolation by lowering physical tension, increasing a sense of control and self-efficacy, ultimately increasing resilience in the parents of infected children.27 The caregivers experienced a sense of relief and expressed positive feelings for being treated in a nonjudgmental way. As previously described, the possibility to freely talk about their own emotions without being censored is a path of growth for HIV-positive subjects.28

In conclusion, attention needs to be paid to both psychosocial and biomedical aspects of pediatric AIDS. It is important to involve caregivers and family members who are in close contact with the HIV-infected child. With little effort and easy to perform and sustainable interventions, the bio-psychosocial state of HIV-infected children and their families may be substantially improved.

Appendix: Psychotherapy Sessions

First meeting

A psychologist expert in HIV guided the meeting; a younger psychologist and a social worker were also actively involved. All the group members met in a friendly context. Parents were invited to introduce themselves and their families and share their expectations. The aims of the group support were presented, and the participants were asked to fill the standardized cognitive instruments. Parents reported their fears and feelings of isolation in relation to their and/or their children's illness. Some of the parents reported fear for their own disease. A major issue was related to the disclosure of the HIV status.

Second meeting

An overall increased acknowledgment of the pain and the distress related to the issues raised by parents was recorded and openly discussed. Most interventions focused on the sense of guilt for having vertically transmitted the infection, the fear of illness and death, the uncertainty about the future. Reasons supporting early disclosure to children were gently introduced.

Third meeting

The inner resources of the parents/carer and the family resources were explored under the guide of therapists. The barriers to disclosure were often related to the perceived misconception of the HIV infection in the ‘outside world’. The fear of death was strongly rooted in those participants who already had experienced a death for HIV in the family and was contained by an element of life expressed by others. The risk of family break up by a member of the group was counterbalanced by someone else's confidence as well.

Fourth meeting

A conscious sense of guilt arose for the transmission of the infection, in association with the idea of having betrayed their task to be bearers of life rather than death.

Fifth meeting

In this session, the attendees were invited to take advantage from available social services. Particularly, a social worker provided information on local resources, as well as financial resources to support HIV-infected subjects. The physicians of the medical service joined the group, and parents were able to directly and openly ask questions and make comments. The physicians stressed the efficacy of HAART in fostering a full control of the disease, preventing HIV progression, and allowing a full normal life, if optimal adherence to treatment was reached.

Sixth meeting

This session was named 'Not when, rather how' and addressed HIV disclosure, because therapists spoke about the scattered experiences and built a roleplaying to give simple explanations to young children or information about the nature and consequences of illness to older children.

Seventh meeting

In this session, the focus was on consolidation of earlier meetings in order to help the caregiver to find confidence and language competences to talk to the children.

Eighth meeting

In the final session, tests were administered to caregivers in order to obtain a feedback on empathetic support and cognitive advance.

Acknowledgments

All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. The study was supported in part from the nonprofit associations Essere Bambino and ANLAIDS Campania.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Wagnild GM. Collins JA. Assessing resilience. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2009;47:28–33. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20091103-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glossary of CMHA Mental Health Promotion Tool Kit. http://www.cmha.ca/mh_toolkit/intro/pdf/intro.pdf. [Feb 27;2013 ]. http://www.cmha.ca/mh_toolkit/intro/pdf/intro.pdf

- 3.Benton TD. Ifeagwu JA. HIV in adolescents: What we know and what we need to know. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellins CA. Ehrhardt AA. Families affected by pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: Sources of stress and coping. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15:S54–S60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiener L. Mellins CA. Marhefka S. Battles HB. Disclosure of an HIV diagnosis to children: History, current research, and future directions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:155–166. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267570.87564.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. 2011:1–1268. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannattasio A. Officioso A. Continisio GI, et al. Psychosocial issues in children and adolescents with HIV infection evaluated with a World Health Organization age-specific descriptor system. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32:52–55. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181f51907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler AM. Williams PL. Howland LC, et al. Impact of disclosure of HIV infection on health-related quality of life among children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2009;123:935–943. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammami N. Nöstlinger C. Hoerée T. Lefèvre P. Jonckheer T. Kolsteren P. Integrating adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy into children's daily lives: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e591–597. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vreeman RC. Nyandiko WM. Ayaya SO. Walumbe EG. Marrero DG. Inui TS. The perceived impact of disclosure of pediatric HIV status on pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence, child well-being, and social relationships in a resource-limited setting. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:639–649. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellins CA. Brackis-Cott E. Dolezal C. Abrams EJ. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:1035–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143646.15240.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaz LME. Eng E. Maman S. Tshikandu T. Behets F. Telling children they have HIV: Lessons learned from findings of a qualitative study in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:247–256. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blasini I. Chantry C. Cruz C, et al. Disclosure model for pediatric patients living with HIV in Puerto Rico: Design, implementation, and evaluation. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:181–189. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannattasio A. Albano F. Giacomet V. Guarino A. The changing pattern of adherence to antiretroviral therapy assessed at two time points, 12 months apart, in a cohort of HIV-infected children. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:2773–2778. doi: 10.1517/14656560903376178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupuy H. The psychological general well-being (PGWB) index. In: Wenger N, editor; Mattson M, editor; Furberg C, editor. Assessment of Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies. Washington, DC: Le Jacq Publishing; 1984. pp. 170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowell I. Newell C. The general well-being schedule. In: McDowell I, editor; Newell C, editor. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 2nd. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marteau TM. Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Br J Clin Psychol. 1992;31:301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spielberger C. Gorsuch R. Lushene R. Vagg P. Jacobs G. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI (Form Y) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mystakidou K. Tsilika E. Parpa E. Sakkas P. Vlahos L. The psychometric properties of the Greek version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in cancer patients receiving palliative care. Psychol Health. 2009;24:1215–1228. doi: 10.1080/08870440802340172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wool C. Cerutti R. Marquis P. Cialdella P. Hervié C ISGQL. Italian Study Group on Qulity of Life. Psychometric validation of two Italian quality of life questionnaires in menopausal women. Maturitas. 2000;35:129–142. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosma H. Lamers F. Jonkers CCM. van Eijk JT. Disparities by education level in outcomes of a self-management intervention: The DELTA trial in The Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:793–795. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.7.pss6207_0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaud PA. Suris JC. Thomas LR. Kahlert C. Rudin C. Cheseaux JJ. To say or not to say: A qualitative study on the disclosure of their condition by human immunodeficiency virus-positive adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen I. Bhana A. Myeza N, et al. Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care. 2010;22:970–978. doi: 10.1080/09540121003623693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendias EP. Paar DP. Perceptions of health and self-care learning needs of outpatients with HIV/AIDS. J Community Health Nurs. 2007;24:49–64. doi: 10.1080/07370010709336585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Disclosure of illness status to children and adolescents with HIV infection. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatrics AIDS. Pediatrics. 1999;103:164–166. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding H. Wilson CM. Modjarrad K. McGwin G. Tang J. Vermund SH. Predictors of suboptimal virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents: Analyses of the reaching for excellence in adolescent care and health (REACH) project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1100–1105. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novack DH. Cameron O. Epel E, et al. Psychosomatic medicine: The scientific foundation of the biopsychosocial model. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31:388–401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.5.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zea MC. Reisen CA. Poppen PJ. Bianchi FT. Echeverry JJ. Disclosure of HIV status and psychological well-being among Latino gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]