Abstract

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is disproportionately impacting young African Americans. Efforts to understand and address risk factors for unprotected sex in this population are critical in improving prevention efforts. Situational risk factors, such as relationship type and substance use before sex, are in need of further study. This study explored how established cognitive predictors of risky sexual behavior moderated the association between situational factors and unprotected sex among low-income, African American adolescents. The largest main effect on the number of unprotected sex acts was classifying the relationship as serious (event rate ratio=10.18); other significant main effects were alcohol use before sex, participant age, behavioral skills, and level of motivation. HIV information moderated the effect of partner age difference, motivation moderated the effects of partner age difference and drug use before sex, and behavioral skills moderated the effects of alcohol and drug use before sex. This novel, partnership-level approach provides insight into the complex interactions of situational and cognitive factors in sexual risk taking.

Introduction

In the United States the HIV/AIDS epidemic disproportionately impacts youth and African Americans. Although they made up only about 20% of the population, young people between the ages of 13–29 years represented nearly 40% of new HIV infections in 2009; among all persons between the ages of 13–24 who were infected, 65% were African American.1 Given that the primary mode of infection among African American youth is sexual transmission,2 continued efforts to delineate predictors of unprotected sex in this population are critical in improving and targeting prevention efforts.

Prior research on predictors of HIV risk behaviors among adolescents can roughly be divided into two literatures. First are studies that attempt to identify individual traits and situational factors that, while not specific in their association with HIV, do predict engagement in HIV risk behaviors. Individual traits include factors such as developmental effects, personality characteristics, poverty, and mental health. Situational and ecological factors include the context in which the sexual behavior occurs (e.g., the type of relationship, substance use prior to sex), as well as the larger ecological context (e.g., levels of parental monitoring). The primary goal of this approach is to identify individuals who are at risk, and situations that potentiate risk in order to develop interventions that specifically target these factors without necessarily specifying the causal chain linking the risk factors with the outcomes. Within this collection of literature, three of the most widely studied predictors of sexual risk are relationship type (i.e., serious versus casual),3–7 substance use prior to sex,8–12 and partner age difference.13,14 The second major collection of literature focuses on cognitive factors directly related to sexual risk behavior, such as HIV knowledge, attitudes towards risk and prevention behaviors, expectations, motivations, and abilities related to risky or safer sex.15,16 Here, the goal is to identify cognitive factors related to HIV that can be changed through intervention so as to facilitate the individual's engagement in protective behaviors.

In general, these literatures have developed in relative isolation from one another, one predominately from epidemiology, and the other from health behavior theory, but there is great value in integrating these approaches. As an example of the potential of integrating these two approaches, consider the association between substance use and unprotected sex. If substance use prior to sex is found to be predicted by certain cognitive factors, one could intervene to reduce substance use and thereby reduce risky sexual behavior. Alternatively, one could develop interventions that do not reduce substance use, but rather change cognitions or skills in such a way to reduce the effects of substance use on condom use, and thereby reduce unprotected sex during intoxication. For example, a harm reduction strategy may teach substance users techniques for preparing for condom use prior to intoxication. Identifying moderated relations such as this increases the number of avenues for prevention.

Unprotected sex in adolescent relationships

Evidence suggests that the most frequent adolescent relationship or partnering pattern is best described as “serial monogamy” (i.e., having multiple sequential non-overlapping sexual relationships).17,18 This pattern places adolescents at particular risk for acquisition of HIV and other STIs for several reasons. First, when an STI occurs in the context of a relationship, the duration of the infectious period of the disease is often longer than the gap between adolescents' sequential relationships, thus placing the new partner at risk for STIs since an adolescent may infect a new partner before knowing that he or she is infected.19 Second, condom use is most likely to occur early in adolescents' romantic relationships, and condom use declines quickly over time once the relationship is considered “serious”.20,21 Third, the average required duration before a relationship is considered “serious” is short; one study found the average time-frame for young women's relationships to progress from being treated as new to being considered serious enough for unprotected sex was 21 days.21 Fourth, these relationship factors are nested within the developmental context where the norm is for a maturational process where heterosexual individuals switch from condom use to other means of birth control or the desire to have children.22,23 If adolescents are indeed experiencing rapid sexual partner turnover and ceasing condom use with their partners because they are quick to define their relationships as serious, then HIV and other STIs have the opportunity to be transmitted more efficiently across these multiple partnerships.

Substance use and unprotected sex

A relatively large body of literature has examined the relationship between alcohol use and sexual risk, and these various studies have produced inconsistent findings. These inconsistencies may be partially due to differing methodologies that have been used to examine this relationship. Research using a global association methodology (i.e., average rates of alcohol use and risky sex during a discrete retrospective window) has generally found positive associations between risky sex and alcohol use in general populations.24–26 Importantly, evidence suggests that teens tend to overestimate the association between drinking and sexual risk in retrospective assessments.27 Event-level analyses of multiple occasions of alcohol use and sex in the same person over time improve upon this approach by specifically mapping alcohol and condom use onto a sexual encounter or partner, and this type of analysis has been conducted using either retrospective accounts of behavior or prospective daily diaries. Both of these approaches have yielded mixed results, with some reporting positive associations between alcohol use and sexual risk,26,28 and others finding no association.27,29,30

Drug use has also been found to be associated with risky sexual behavior in adolescent populations using both global association and event-level studies, including marijuana use,31–33 amphetamine use,34 polysubstance use,35 and studies that measure drug use more generally.36–39 However, some event-level studies have failed to find an association between drug use and risky sex, particularly when measuring marijuana use,34,40 indicating that the association between drug use and sexual risk may not be consistent across all of adolescents. Furthermore, African American adolescents and adults have been found to drink and use drugs significantly less frequently compared to White individuals,35,41–47 and the association between substance use and sexual risk may not be consistent across racial groups.

Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills (IMB)

The Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model is a widely-used framework for studying HIV risk behavior and developing prevention interventions,48 and this model has been applied to HIV risk and behavior change specifically in African American youth.15 The IMB Model draws on the tenets of Social Cognitive Theory49 and Theory of Reasoned Action,50 and it asserts that the fundamental determinants of engaging in behaviors that prevent HIV acquisition are the combined effects of having: (a) HIV-related information and prevention knowledge, (b) motivation to become/stay safer, and (c) necessary skills to engage in prevention behaviors, including self-efficacy to use condoms.51 The literature on heterosexual youth and adults generally supports the association between the components of the IMB model and sexual risk behavior in both observational studies16,51–56 and tests of interventions.57,58 However, evidence suggests that motivation and behavioral skills may play a more proximal role in influencing sexual risk than HIV-related information.16,53

Most studies examining the influence of IMB variables on sexual risk behavior have examined either individual associations between the components of the IMB model on a variety of sexual risk behaviors or have focused on evaluating the overall fit of the IMB model in accounting for the variance in sexual risk. To our knowledge, very little research has examined whether these variables (i.e., HIV knowledge, motivation, and behavior skills) interact with situational variables (e.g., substance use prior to sex, partner type) in predicting sexual risk behavior. It may be that individuals with varying degrees of endorsement of IMB constructs experience differential associations between situational variables and sexual risk. For example, it is possible that individuals who are highly motivated to avoid unprotected sex are less likely to abandon condom use once a relationship becomes “serious” compared to youth who are lower in such motivation.

While these moderating effects have not previously been well explored in the literature, evidence from the substance use literature suggests that the association between situational variables and sexual risk are not consistent across all youth and adolescents, and HIV knowledge, motivation, and behavioral skills may help to further explain these inconsistencies. For example, a study of college males found that alcohol use was linked to decreased condom use with casual partners but not with new or serious partners.28 Additionally, a recent study of young men who have sex with men found that sensation seeking moderated the association between drinking and sexual risk, such that there was only a positive association between these variables in high sensation seekers.59 Finally, a study of college students found that those who were higher in self-efficacy were more likely to use condoms while drunk than those lower on this domain.52

The purpose of the current manuscript is to explore how established cognitive predictors of risky sexual behavior may moderate the association between situational factors and unprotected sex using a cross-sectional Partner-Level Model (PLM); if moderation is found, it suggests that approaches to positively influence cognitions may help sever the association between situational factors and unhealthy outcomes. In our sample of very low-income, African American adolescents, we used the sexual partnership, rather than the individual, as the unit of analysis. We hypothesized that being in a serious relationship, having older partners, and using alcohol or drugs before sex would all increase the risk of unprotected sex, but greater behavioral skills, motivation, and information would diminish these influences.

Methods

This study, known as the Gene, Environment, Neighborhood Initiative (GENI), included a community sample of 592 adolescents aged 13 through 18 years, and their primary caregivers. Their average age was 15.9 years and 48.8% of GENI participants were male. Nine participants did not provide information about sexual behavior, leaving an analytic sample of 583 participants (98.5% of the GENI sample). The adolescents and caregivers were from predominantly African American, very low-income neighborhoods in the southern U.S. Participants were recruited from a community-based, multiple cohort longitudinal study with annual data collection, the Mobile Youth Study (MYS); the MYS has been described in detail elsewhere.60,61 Participation in GENI involved an approximately 2½ h interview for both the adolescent and his/her caregiver. Interviews were conducted between March 2009 and October 2011. All measures were collected using an audio computerized self-administered interview (ACASI) approach, which removes the need for interviewers to ask sensitive questions and may provide a more accurate assessment of youth risk behaviors.62,63 Written parental consent and youth assent were obtained. Caregivers and adolescents were compensated for their participation. Procedures for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Northwestern University, Virginia Commonwealth University, and the University of Alabama.

Measures

General demographics

Caregivers reported on the sex and age of the adolescent.

Sexual risk behaviors

The HIV-Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships (H-RASP)64 is a computerized self-administered interview designed to assess sexual behavior and associated situational and contextual variables at the level of the sexual partnership. The H-RASP was based on AIDS-Risk Behavior Assessment (ARBA)65 but adapted to collect information within sexual partnerships. Both the H-RASP and the ARBA have been used repeatedly with youth populations, including ethnically diverse adolescents, adolescents with psychiatric disorders, and young MSM.65–67 The H-RASP included information on characteristics of and behaviors with up to three sexual partners during the 12 months prior to the interview. The sexual risk outcome was an estimate of the number of unprotected vaginal and anal sex acts within each partnership; only male–female and male–male partnerships (reported by seven participants) were included in the analysis. The participant was asked the number of sex acts and the frequency of condom use with each partner. In order to calculate the number of unprotected sex acts, we recoded the frequency of condom use to reflect the percentage of time that the participant did NOT use a condom; therefore, frequency of no condom use was coded as: never=100%; less than half the time=75%; about half the time=50%; more than half the time=25%; and always=0%. This proportion was then multiplied by the number of sex acts. For example, if a participant reported 10 sex acts with a partner and condom use about half the time, then the estimated number of unprotected sex acts was estimated at 5 (10 X .5).

Partner and relationship characteristics

The H-RASP included questions about each partner and relationship. Participants were asked about the age difference when sex was initiated (He/She was…−1=younger than you; 0=same age; 1=1–2 years older than you; 2=3–4 years older than you; 3=5 or more years older than you) and whether the partner was considered casual (0) or serious (1); a serious partner was defined as “someone you've had sex with and someone with whom you've had an ongoing relationship with, like a lover, boyfriend or girlfriend, or someone you dated for a while and feel very close to” while a casual partner was defined as “someone you have sex with occasionally or even just one time.”

Alcohol and drug use

For each partner reported in the H-RASP, participants were asked: “How frequently did you drink alcohol before having sex with this partner?” and “How frequently did you use drugs before having sex with this partner?” with a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Responses were recoded to 0=never, 1=sometimes, 2=always.

Information

AIDS knowledge was measured with a 25-question true–false self-report instrument adapted from material created by the Channing Bete Company and used by the Alabama Department of Public Health.68 Examples of the items include “You can tell if a person has HIV by looking at him or her” and “It's important to use only a water-based lubricant with latex condoms.” The number of correct answers for each participant was calculated and then the total scores were divided into quartiles in order to increase the interpretability of the effect sizes. A quartile was then assigned to each participant for use in the analyses.

Motivation

AIDS attitudes and behavioral intentions were assessed using a self-report measure based on IMB model constructs69 and social cognitive theory.70 We computed four scales and performed a Principal Components factor analysis to construct a single motivation factor score. The factor analysis produced one factor with an eigenvalue over one, which explained 48% of the variance. The four scales included in the motivation factor were: (1) Adolescent perception of peer norms, which consisted of two items (e.g., “My friends think that people should use condoms during sexual intercourse”) with four response options ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” and then reverse scored; (2) Adolescent attitudes toward HIV preventive acts, which consisted of three items (e.g., “If I have sex during the next two months, using condoms every time would be:”) with five response options ranging from “very bad” to “very good.” (3) Adolescent intention to prevent AIDS, which consisted of three items (e.g., “I'm planning not to have sexual intercourse at all during the next two months”) with five response options ranging from “very true” to “very untrue.” (4) Adolescent beliefs about condom use, which consisted of five items (e.g., “Condoms take all the fun out of sex”) with five response options ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” For all scales, items were summed to compute a composite score with higher scores representing greater motivation.

Behavioral skills

Behavioral skills were measured as perceived ability to prevent HIV infection by avoiding unprotected sex (i.e. self-efficacy for HIV prevention behaviors).69 Three questions from the self-report AIDS attitudes and behavioral intentions measure were used to create a perceived self-efficacy scale: (1) “I can do things to make sure I don't get AIDS.” (2) “I can refuse to have sexual intercourse if my partner won't use a condom.” (3) “I can tell my partner I want to use a condom during sexual intercourse.” All items had four response options ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy to practice prevention. The mean response from the three items was calculated to represent the perceived self-efficacy score, which ranged from zero to three. Given the interpretable zero value, this variable was entered in the analysis uncentered.

Analyses

We used Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) statistical software and procedures outlined by Raudenbush and Bryk (2002)71 to examine the moderating effects of cognitive domains on the relationship between situational variables and sexual risk behavior using a cross-sectional Partner-Level Model; note that only adolescents who were sexually active in the past year were included in this analysis. HLM is well suited to this design because it can account for dependency in observations in data that contain a nested or multilevel structure. In this case, sexual partnerships (Level 1) are nested within participants (Level 2). Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used to model frequency of unprotected sex acts as the dependent variable; to account for outliers the data were Winsorized at two standard deviations from the mean. A Poisson distribution was used in estimating the proportion of unprotected sex acts and the model also accounted for overdispersion in the outcome variable. Estimates were made from the population-average model using robust standard errors.

Results

Of the 583 participants who completed the H-RASP, 224 (38.4%) were sexually active in the past year and reported a total of 306 sexual partnerships during that time. The majority (72.8%) of participants reporting any sexual relationships in the previous year only had one such relationship, while 17.9% had two sexual relationships, and 9.4% reported three. Of participants who reported a sexual relationship, the average age was 16.4 years, and 62% were males; significantly fewer nonsexually active participants were male (41%, χ2=23.6, df=1, p<0.001) and they were younger (mean age=15.6, p<0.001).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participant and relationship factors across all sexual partnerships. There was an average of 3.70 episodes of unprotected sex in each partnership; the intraclass correlation (ICC) indicated 43% of the variance in unprotected sex was across participants and 57% across partnerships (i.e., change within participants). Partners were close to the same age as the participant on average (partner age difference mean=0.30), and 68.6% of partnerships were described as serious. Alcohol and drug use before sex was infrequent; 90.5% and 87.3% reported never using alcohol or drugs before sex, respectively. Sexually active adolescents scored higher than nonsexually active adolescents on information (mean number correct=18.6 vs. 17.7, p<0.001) and behavioral skills (mean=2.6 vs. 2.4, p<0.001).

Table 1.

IMB and Relationship Variables

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Range | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMB Variables (n=224) | |||

| Motivation factor | 0 (1) | −2.66–1.83 | |

| Behavioral skills | 2.63 (.73) | 0–3 | |

| Information | |||

| Number correct (out of 25) | 18.58 (2.66) | 11–24 | |

| Number correct - quartiles | 1.33 (1.15) | 0–3 | |

| Relationship Variables (n=306) | |||

| Number of unprotected sex acts (count)a | 3.70 (9.90) | 0–62 | |

| Serious relationship (dichotomous, 0-1) | 68.6% | ||

| Partner age difference (ordinal, −1 to 3) | 0.30 | 1.07 | |

| Younger | 29.1% | ||

| Same age | 27.1% | ||

| 1-2 years older | 31.0% | ||

| 3-4 years older | 10.1% | ||

| 5+years older | 2.6% | ||

| Alcohol use before sex with partner (ordinal) | 0.12 (.39) | 0–2 | |

| Never | 90.5% | ||

| Sometimes | 7.2% | ||

| Always | 2.3% | ||

| Drug use before sex with partner (ordinal) | 0.16 (.45) | 0–2 | |

| Never | 87.3% | ||

| Sometimes | 9.5% | ||

| Always | 3.3% | ||

Winsorized to 2 standards deviations

The results of the main effects HLM model predicting the rate of unprotected sex in any given sexual relationship are shown in Table 2. Results for all effects are presented using the event-rate ratio (ERR), which provides an estimate of the change in the event-rate of the outcome variable for each one unit increase in the independent variable. Identifying the relationship as “serious” resulted in over 10 times the rate of unprotected sex compared to casual relationships. Alcohol use before sex was also associated with higher likelihood of unprotected sex (ERR=2.06, p<0.05, 95% CI [1.12, 3.80]). In terms of between-subjects effects, older age of participant (ERR=1.36, p<0.05, 95% CI [1.06, 1.74]) and having more behavioral skills (ERR=2.33, p<0.001, 95% CI [1.56, 3.48]) were both associated with a higher rate of unprotected sex, while greater motivation decreased the rate of unprotected sex acts (ERR=0.39, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.32, 0.49]).

Table 2.

Effects of Partner and Relationship Characteristics and IMB Factors on the Number of Unprotected Sex Acts

| Fixed effect | Event rate ratio | 95% C.I. | Coefficient | Standard error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | |||||

| Child gender, male | 0.90 | 0.47, 1.75 | −0.10 | 0.35 | NS |

| Child age | 1.36 | 1.06, 1.74 | 0.31 | 0.14 | <.05 |

| Partner age difference | 1.12 | 0.80, 1.57 | 0.11 | 0.61 | NS |

| Serious relationship | 10.18 | 3.09, 33.59 | 2.32 | 0.17 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use before sex with partner | 2.06 | 1.12, 3.80 | 0.72 | 0.32 | <0.05 |

| Drug use before sex with partner | 1.45 | 0.82, 2.54 | 0.37 | 0.29 | NS |

| Information (HIV quiz – quartiles) | 1.07 | 0.85, 1.35 | 0.07 | 0.19 | NS |

| Motivation factor | 0.39 | 0.32, 0.49 | −0.94 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Behavioral skills (self-efficacy) | 2.33 | 1.56, 3.48 | 0.85 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

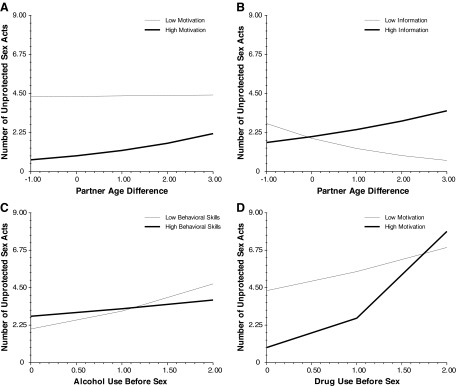

To further understand how information, motivation, and behavioral skills may affect the rate of unprotected sex, we tested the interaction of these variables with partner-specific variables (Table 3). While being in a serious relationship had the largest independent effect on the rate of unprotected sex, it did not have any interaction effects with the IMB variables. The age difference between participants and their sexual partners did not have a significant main effect on unprotected sex, but the interactions of age difference with motivation (ERR=1.20, p<0.05, 95% CI [1.01, 1.43]; Fig. 1A) and information (ERR=1.32, p<0.01, 95% CI [1.10, 1.58]; Fig. 1B) were significant. Individuals with lower motivation had more unprotected sex than individuals with higher motivation overall. Although sexual partner age did not appear to affect likelihood of sexual risk for those low in motivation, having older partners degraded the protective effect of motivation on sexual risk for those higher in motivation (see Fig. 1A). Also, as the partner age difference increased, participants with greater HIV information had more unprotected sex, but participants with a lower level of information reduced the number of unprotected sex acts (Fig. 1B).

Table 3.

Cross-Level Interactions Between Level 1 and Level 2 Effects in Predicting Sexual Risk

| Fixed effect | Event rate ratio | 95% C.I. | Coefficient | Standard error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious relationship | |||||

| X Motivation factor | 0.47 | 0.20, 1.12 | −0.76 | 0.44 | NS |

| X Behavioral skills | 2.06 | 0.86, 4.91 | 0.72 | 0.44 | NS |

| X Information | 2.04 | 0.99, 4.20 | 0.71 | 0.36 | NS |

| Age difference | |||||

| X Motivation factor | 1.20 | 1.01, 1.43 | 0.18 | 0.09 | <0.05 |

| X Behavioral skills | 0.83 | 0.64, 1.07 | −0.19 | 0.13 | NS |

| X Information | 1.32 | 1.10, 1.58 | 0.28 | 0.09 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use before sex | |||||

| X Motivation factor | 0.84 | 0.53, 1.35 | −0.17 | 0.24 | NS |

| X Behavioral skills | 0.44 | 0.29, 0.67 | −0.83 | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| X Information | 1.07 | 0.72, 1.59 | 0.07 | 0.20 | NS |

| Drug use before sex | |||||

| X Motivation factor | 1.72 | 1.19, 2.48 | 0.54 | 0.18 | <0.01 |

| X Behavioral skills | 0.40 | 0.25, 0.64 | −0.92 | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| X Information | 0.75 | 0.52, 1.06 | −0.29 | 0.18 | NS |

FIG. 1.

IMB and partner characteristic interactions. (A) The effect of partner age difference X motivation on unprotected sex. (B) The effect of partner age difference X information on unprotected sex. (C) The effect of alcohol use before sex X behavioral skills on unprotected sex. (D) The effect of drug use before sex X motivation on unprotected sex.

There was also a significant interaction between behavioral skills and both alcohol use (ERR=0.44, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.67]) and drug use (ERR=0.40, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.25, 0.64]) in predicting the rate of unprotected sex. Adolescents higher in behavioral skills were less influenced by the effects of alcohol or drug use on unprotected sex. Participants with lower behavioral skills had a stronger positive association between unprotected sex and both alcohol and drug use before sex (Fig. 1C; note that the interaction between motivation and drug use in predicting unprotected sex is not illustrated in this figure, but the pattern of findings is comparable). There was also a significant interaction between motivation and drug use before sex (ERR=1.72, p<0.01, 95% CI [1.19, 2.48]; Fig. 1D) in predicting unprotected sex. Adolescents with low motivation had a consistently high level of unprotected sex, while adolescents with high motivation were more affected by using drugs before sex (i.e., drug use eliminated the protective effects of motivation).

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to understand how cognitive factors related to HIV (i.e., information, motivation, and behavioral skills) interact with situational factors to affect HIV risk behaviors. To achieve this aim, we examined the moderating effects of cognitive domains on the relationship between situational variables and sexual risk behavior using a cross-sectional Partner-Level Model (PLM).64 These findings can be used to inform interventions that aim to increase levels of certain cognitive factors that protect against sexual risk or to help break the association between certain situational variables (e.g., alcohol and drug use) and unprotected sex.

The strongest situational predictor of unprotected sex in these analyses was whether the adolescent classified the relationship as serious. In fact, unprotected sex was 10 times more likely in serious relationships compared to casual relationships. Additionally, none of the IMB variables moderated this relationship, indicating that the influence of serious partnerships on risk does not differ across these cognitive domains. Given that adolescents are quick to classify their relationships as serious,21 and they often have multiple nonoverlapping serious relationships in relatively short periods of time,17,18 they may have unprotected sex with multiple partners over time, thereby increasing long-term risk of acquiring HIV, other STIs and unintended pregnancy. When planning interventions to reduce unprotected sex, it is important to understand the differences between casual and serious relationships and the concept of “serial monogamy” or sequential serious relationships. Researchers and practitioners who design interventions should consider including information about what it means to be in a serious relationship in adolescence, how long these relationships generally last, and highlight the increased probability over time of having unprotected sex in several serious relationships. It may be useful to point out to adolescents that, at least among young men who have sex with men, the majority of HIV transmissions are from a serious partner;72 one study of HIV-positive YMSM found decreasing but still high rates of unprotected sex with both steady and casual partners in the previous 3 months.73

Previous research has linked both alcohol and drug use to risky sexual behavior, but these findings have been inconsistent in adolescents and young adults.9,74 Our results are consistent with some previous findings of a positive main effect of alcohol use prior to sex on sexual risk, but we did not find evidence of a main effect of drug use prior to sex and sexual risk. Importantly, the effect of alcohol use on the number of unprotected sex acts is small compared to the effect of being in a serious partnership. Drug use before sex was not significantly associated with unprotected sex, although we did not distinguish between different types of substances used; evidence suggests that some drugs, such as stimulants, are more associated with unprotected sex than others, such as marijuana.75 These analyses, though, did find evidence for moderating effects of some IMB variables on the association between sexual risk and alcohol and drug use prior to sex. Among adolescents with strong behavioral skills, using alcohol or drugs before sex was not strongly related to frequency of unprotected sex. However, adolescents with low behavioral skills demonstrated sharp increases in unprotected sex as alcohol and drug use prior to sex increased. Interestingly, the results of our linear model suggest that when there was no alcohol or drug use before sex, adolescents with stronger behavioral skills had more unprotected sex than adolescents with lower behavioral skills. An important consideration when interpreting this result is that overall the sample had a very high level of behavioral skills so the effect is for variation from moderately high to high behavioral skills.

Similarly, motivation also moderated the effect of drug use prior to sex on sexual risk. When never or sometimes using drugs before sex, HIV risk reduction motivation was strongly protective against unprotected sex. However, always using drugs prior to sex reduced this effect substantially, such that differences between low and highly motivated adolescents in sexual risk were small in the context of drug use. Motivation is necessary for youth to engage in consistent condom use,15,76,77 but there are a variety of situational variables, such as drug use, that may override motivation in decisions about condom use. Specifically, adolescents may not have the cognitive abilities in place to be able to understand how their behavior and learning are affected by substance use,78 and they may not have the experience with past substance use to know how it will affect them in sexual situations.79 They may also be so impaired by the effects of substance use that their motivations and skills cannot be implemented. This may also be an example of state-dependent learning,80–82 whereas adolescents who learned HIV risk-reduction behavior skills and motivation when they were sober are unable to implement them when they are under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Although there was no significant main effect for partner age on sexual risk, motivation and information were both significant moderators of this effect. Our findings show that even adolescents with higher motivation engaged in more unprotected sex with older partners. The literature indicates that having an older partner has been associated with decreased condom use,13,14 contraceptive use,83 and risky sex and substance use for adolescent girls,84 and that partner age difference may matter more for younger than for older adolescent females.85,86 It was unexpected to find that participants who scored higher on the HIV knowledge quiz had more unprotected sex with older partners than participants with lower scores; a study of African American low-income adolescents also found that greater HIV knowledge was associated with more unprotected sex, although partner age differences were not examined.87 It is also possible that greater HIV knowledge is a result of higher levels of unprotected sex. Future research should explore these unexpected interactions and ascertain whether there are other factors impacting these results.

Across these interactions, a general pattern is one in which the IMB factors are most protective at lower level of situational risks (i.e., no drug or alcohol use, same-age partner), but that their protective effects wane as the situational risks increase. From a prevention standpoint, this pattern is unfortunate because it suggests that interventions that increase HIV protective knowledge and motivations may only increase protective behaviors in low risk situations and contexts. Alternatively, if we found that increased knowledge, motivation, and skills were protective against situational risks, it would be cause for optimism about the impact of existing social-cognitive interventions for reducing the risks associated with situational factors like drug use or older partners. Alternative intervention approaches may be necessary to address situational risks. For example, these alternative interventions could directly address the situational factors (e.g., reducing drug use), provide skills relevant to specific contexts (e.g., how to advocate for and use condoms while intoxicated), or develop novel approaches for addressing state dependent learning, such as reaching youth with education during periods of substance use (e.g., through a mobile app). Of course, the pattern of our results needs to be replicated in other studies with other designs before such a general conclusion that IMB factors are less protective in high risk situations. Little research has been conducted so far on the interplay of multiple levels of influence (i.e., individual, situational, dyadic) on HIV risk behaviors, but such studies have recently been called for to advance the science of HIV prevention88 and would increase understanding of the interplay of situational and social-cognitive factors.

One unanticipated result was the significant main effect of behavioral skills on sexual risk, with greater behavioral skills resulting in more unprotected sex. A literature review of adolescent sexual behavior and intentions found that eleven studies reported on the relationship between self-efficacy and various sexual behaviors; seven studies reported that higher behavioral skills resulted in lower sexual risk and five reported no associations (one study had results in both categories).89 However, a study of adolescents seeking psychiatric care found that youths with higher behavioral skills engaged in more sexual risk taking. It may be due to the cross-sectional nature of the study or there may be unexamined factors that would help to explain this finding. For example, perhaps adolescents with more behavioral skills also have more sex, which provides more opportunities for unprotected sex acts to occur. Further research that examines the complex linkages among the various risk factors as well as the interaction of motivation and behavioral skills would be helpful in understanding how to develop more effective interventions to prevent risky sexual behavior in adolescents.

Limitations

There are several limitations to note regarding this study. The sample may not be generalizable to adolescents from other racial/ethnic groups, other parts of the country, or from higher-income families. The data are cross-sectional, so the extent of the effects of high risk sex on motivation, behavioral skills, and information cannot be known. Also, only sexually active adolescents were included in this analysis, because it is based on sexual partnership characteristics; including adolescents who were not sexually active or who had oral but not vaginal or anal sex may result in different findings. As there are some significant differences between the sexually active and nonsexually active groups, some of the findings, particularly the unexpected ones, may be due to the fact that adolescents who are having sex are already self-selected as a higher risk group. The sexually active group was older and included more males than the nonsexually active group, both of which are risk factors for increased sexual activity. They also scored higher on the HIV information and self-efficacy measures, which we would expect to be protective factors against engaging in risky sexual activity.

Despite these limitations, this study provides insight into the complex interactions between situational and cognitive factors in predicting sexual risk taking among African American adolescents, a population disproportionately affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It adds to the relatively new literature which uses partner-level approaches in examining factors associated with sexual risk taking.64 Additionally, our findings provide insight for designing interventions for individuals or couples that address the complex relationships between situational and cognitive predictors of sexual risk taking.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (RO1DA025039). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.CDC. HIV among Youth. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/youth/pdf/youth.pdf. [Nov 15;2012 ]. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/youth/pdf/youth.pdf

- 2.CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS among adolescents and young adults in the United States and 5 U.S. dependent areas, 2006–2009. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2012:17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misovich SJ. Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: Evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1:72–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Civic D. College students' reasons for nonuse of condoms within dating relationships. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:95–105. doi: 10.1080/009262300278678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noar SM. Zimmerman RS. Atwood KA. Safer sex and sexually transmitted infections from a relationship perspective. In: Harvey JH, editor; Wenzel A, editor; Sprecher S, editor. The Handbook of Sexuality in Close Relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 519–544. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manlove J. Wildsmith E. Ikramullah E. Terry-Humen E. Schelar E. Family environments and the relationship context of first adolescent sex: Correlates of first sex in a casual versus steady relationship. Soc Sci Res. 2012;41:861–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosby RA. DiClemente RJ. Wingood GM. Sionéan C. Cobb BK. Harrington K. Correlates of unprotected vaginal sex among African American female adolescents: Importance of relationship dynamics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:893–899. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.9.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper ML. Orcutt HK. Alcohol use, condom use and partner type among heterosexual adolescents and young adults. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:413–419. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parks KA. Hsieh YP. Collins RL. Levonyan-Radloff K. Daily assessment of alcohol consumption and condom use with known and casual partners among young female bar drinkers. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1332–1341. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott-Sheldon LAJ. Carey MP. Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown JL. Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford K. Sohn W. Lepkowski J. Characteristics of adolescents' sexual partners and their association with use of condoms and other contraceptive methods. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:100–105. 132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiClemente RJ. Wingood GM. Crosby RA, et al. Sexual risk behaviors associated with having older sex partners: A study of black adolescent females. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:20–24. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher WA. Williams SS. Fisher JD. Malloy TE. Understanding AIDS risk behavior among sexually active urban adolescents: An emprical test of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh JL. Senn TE. Scott-Sheldon LA. Vanable PA. Carey MP. Predicting condom use using the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model: A multivariate latent growth curve analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9284-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ott MA. Katschke A. Tu W. Fortenberry JD. Longitudinal associations among relationship factors, partner change, and sexually transmitted infection acquisition in adolescent women. Sexual Transm Dis. 2011;38:153–157. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f2e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris AE. Ford K. Sexual experiences and condom use of heterosexual, low-income African American and Hispanic youth practicing relative monogamy, serial monogamy, and nonmonogamy. Sexual Transm Dis. 1999;26:17–25. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foxman B. Newman M. Percha B. Holmes KK. Aral SO. Measures of sexual partnerships: lengths, gaps, overlaps, and sexually transmitted infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:209–214. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000191318.95873.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustanski B. Newcomb ME. Clerkin EM. Relationship characteristics and sexual risk-taking in young men who have sex with men. Health Psychol. 2011;30:597–605. doi: 10.1037/a0023858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortenberry JD. Tu W. Harezlak J. Katz BP. Orr DP. Condom use as a function of time in new and established adolescent sexual relationships. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:211–213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capaldi DM. Stoolmiller M. Clark S. Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and association with STD contraction. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:394–406. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dogan SJ. Stockdale GD. Widaman KF. Conger RD. Developmental relations and patterns of change between alcohol use and number of sexual partners from adolescence through adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:1747–1759. doi: 10.1037/a0019655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinhardt LS. Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryan A. Ray LA. Cooper ML. Alcohol use and protective sexual behaviors among high-risk adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:327–335. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leigh BC. Morrison DM. Hoppe MJ. Beadnell B. Gillmore MR. Retrospective assessment of the association between drinking and condom use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:773–776. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaBrie J. Earleywine M. Schiffman J. Pedersen E. Marriot C. Effects of alcohol, expectancies, and partner type on condom use in college males: Event-level analyses. J Sex Res. 2005;42:259–266. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tubman JG. Langer LM. “About last night”: The social ecology of sexual behavior relative to alcohol use among adolescents and young adults in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:449–461. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison DM. Gillmore MR. Hoppe MJ. Gaylord J. Leigh BC. Rainey D. Adolescent drinking and sex: Findings from a daily diary study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35:162–168. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.162.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kingree JB. Betz H. Risky sexual behavior in relation to marijuana and alcohol use among African-American, male adolescent detainees and their female partners. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kingree JB. Braithwaite R. Woodring T. Unprotected sex as a function of alcohol and marijuana use among adolescent detainees. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson BJ. Stein MD. A behavioral decision model testing the association of marijuana use and sexual risk in young adult women. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:875–884. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9694-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leigh BC. Ames SL. Stacy AW. Alcohol, drugs, and condom use among drug offenders: An event-based analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connell CM. Gilreath TD. Hansen NB. A multiprocess latent class analysis of the co-occurrence of substance use and sexual risk behavior among adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:943–951. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poulin C. Graham L. The association between substance use, unplanned sexual intercourse and other sexual behaviours among adolescent students. Addiction. 2001;96:607–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9646079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker JS. Ryan GW. Golinelli D, et al. Substance use and other risk factors for unprotected sex: Results from an event-based study of homeless youth. AIDS Behavior. 2012;16:1699–1707. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson C. Sweeting H. Haw S. Clustering of substance use and sexual risk behaviour in adolescence: Analysis of two cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000661. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elkington KS. Bauermeister JA. Zimmerman MA. Do parents and peers matter? A prospective socio-ecological examination of substance use and sexual risk among African American youth. J Adoles. 2011;34:1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hensel DJ. Stupiansky NW. Orr DP. Fortenberry JD. Event-level marijuana use, alcohol use, and condom use among adolescent women. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:239–243. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f422ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newcomb ME. Heinz AJ. Mustanski B. Examining risk and protective factors for alcohol use in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: A longitudinal multilevel analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:783–793. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCabe SE. Morales M. Cranford JA. Delva J. McPherson MD. Boyd CJ. Race/ethnicity and gender differences in drug use and abuse among college students. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2007;6:75–95. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallace JM., Jr. Bachman JG. O'Malley PM. Johnston LD. Schulenberg JE. Cooper SM. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: Racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976–2000. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:S67–S75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace JM., Jr. Bachman JG. O'Malley PM. Schulenberg JE. Cooper SM. Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abuse NIoD. Bethesda, MD: 2009. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Administration SAaMHS. Vol. 1. Summary of National Findings; Rockville, MD: 2010. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen P. Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull May. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fishbein M. Ajzen I. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Williams SS. Malloy TE. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol. 1994;13:238–250. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abbey A. Parkhill MR. Buck PO. Saenz C. Condom use with a casual partner: What distinguishes college students' use when intoxicated? Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:76–83. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher WA. Williams SS. Fisher JD. Malloy TE. Understanding AIDS risk behavior among sexually active urban adolescents: An emprical test of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Amico KR. Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25:462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mustanski B. Donenberg G. Emerson E. I can use a condom, I just don't: The importance of motivation to prevent HIV in adolescent seeking psychiatric care. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:753–762. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalichman SC. Cain D. Weinhardt L, et al. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychol. 2005;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson ES. Wagstaff DA. Heckman TG, et al. Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model: Testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:70–79. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jaworski BC. Carey MP. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newcomb ME. Clerkin EM. Mustanski B. Sensation seeking moderates the effects of alcohol and drug use prior to sex on sexual risk in young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behavior. 2011;15:565–575. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bolland JM. Overview of the Mobile Youth Study: University of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Public Health. 2007.

- 61.Park N. Lee B. Bolland J. Vazsonyi A. Sun F. Early adolescent pathways of antisocial behaviors in poor, inner-city neighborhoods. J Early Adolesc SAGE. 2008:185–205. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kissinger P. Rice J. Farley T, et al. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:950–954. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turner CF. Ku L. Rogers SM. Lindberg LD. Pleck JH. Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mustanski B. Starks T. Newcomb ME. Methods for the design and analysis of relationship and partner effects on sexual health. Arch Sex Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0215-9. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donenberg GR. Emerson E. Bryant FB. Wilson H. Weber-Shifrin E. Understanding AIDS-risk behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care: Links to psychopathology and peer relationships. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:642–653. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garofalo R. Herrick A. Mustanski B. Donenberg GR. Tip of the iceberg: Young men who have sex with men, the Internet, and HIV risk. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1113–1117. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Newcomb ME. Ryan DT. Garofalo R. Mustanski B. The effects of sexual partnerships and relationship characteristics on three sexual risk variables in young men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0207-9. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Channing Bete Company I. PS45609. South Deerfield, MA: Channing Bete Company, Inc; 2004. 1996. HIV—How Much Do You Know About It? Edition (08-03-D) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;11:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise control of HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, editor; Peterson JL, editor. Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raudenbush SW. Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models. Second. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sullivan PS. Salazar L. Buchbinder S. Sanchez TH. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23:1153–1162. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips G., 2nd Outlaw AY. Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. Sexual behaviors of racial/ethnic minority young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:S47–53. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior?: A complex answer to a simple question. Curr Direct Psychol Sci. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Volkow ND. Wang GJ. Fowler JS. Telang F. Jayne M. Wong C. Stimulant-induced enhanced sexual desire as a potential contributing factor in HIV transmission. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:157–160. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walsh JL. Senn TE. Scott-Sheldon LA. Vanable PA. Carey MP. Predicting condom use using the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model: A multivariate latent growth curve analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9284-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Williams SS. Malloy TE. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol. 1994;13:238–250. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zeigler DW. Wang CC. Yoast RA, et al. The neurocognitive effects of alcohol on adolescents and college students. Prevent Med. 2005;40:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: A meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bustamante JA. Jordán A. Vila M. González A. Insua A. State dependent learning in humans. Physiol Behav. 1970;5:793–796. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(70)90281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reus VI. Weingartner H. Post RM. Clinical implications of state-dependent learning. Am J Psychiat. 1979;136:927–931. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.7.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goodwin DW. Powell B. Bremer D. Hoine H. Stern J. Alcohol and recall: State-dependent effects in man. Science. 1969;163:1358–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3873.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glei DA. Measuring contraceptive use patterns among teenage and adult women. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leitenberg H. Saltzman H. A statewide survey of age at first intercourse for adolescent females and age of their male partners: Relation to other risk behaviors and statutory rape implications. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29:203–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1001920212732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Halpern CT. Kaestle CE. Hallfors DD. Perceived physical maturity, age of romantic partner, and adolescent risk behavior. Prev Sci. 2007;8:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaestle CE. Morisky DE. Wiley DJ. Sexual intercourse and the age difference between adolescent females and their romantic partners. Persp Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Swenson RR. Rizzo CJ. Brown LK, et al. HIV knowledge and its contribution to sexual health behaviors of low-income African American adolescents. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:1173–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Albarracin D. Tannenbaum MB. Glasman LR. Rothman AJ. Modeling structural, dyadic, and individual factors: The inclusion and exclusion model of HIV related behavior. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9801-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buhi ER. Goodson P. Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory-guided systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]