Abstract

The recognition of pathogenic DNA is important to the initiation of antiviral responses. Here we report the identification of DDX41, a member of the DEXDc family of helicases, as an intracellular DNA sensor in myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs). Knockdown of DDX41 expression by short hairpin RNA blocked the ability of mDCs to mount type I interferon and cytokine responses to DNA and DNA viruses. Overexpression of both DDX41 and the membrane-associated adaptor STING together had a synergistic effect in promoting Ifnb promoter activity. DDX41 bound both DNA and STING and localized together with STING in the cytosol. Knockdown of DDX41 expression blocked activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase TBK1 and the transcription factors NF-κB and IRF3 by B-form DNA. Our results suggest that DDX41 is an additional DNA sensor that depends on STING to sense pathogenic DNA.

Cells of the innate immune response detect viral infection mainly by sensing viral nucleic acids either in the endosomes during the entry of the virus or in the cytosol during viral replication. Thus far, it has been established that the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 sense viral DNA or RNA in the endosome1–3 and the RNA helicases RIG-I, LGP2 and Mda5 sense double-stranded RNA in the cytosol4–7. Many sensors of cytosolic viral DNA have been identified. RIG-I senses cytosolic DNA (B-form DNA) via RNA polymerase III to trigger responses by transcription factor IRF3–dependent type I interferon8,9. AIM2 senses cytosolic DNA (B-form DNA) by activating inflammasome responses via the adaptor ASC10–16. Although the adaptor STING (also called TMEM173, ERIS, MPYS or MITA) has an essential role in sensing cytosolic DNA17–19, the upstream sensors that directly bind the cytosolic DNA remain unknown. IFI16, an AIM2-like molecule, uses STING for sensing cytosolic DNA20. Notably, knockdown of IFI16 expression leads to slightly lower interferon-β (IFN-β) responses to cytosolic DNA, whereas knockdown of STING expression leads to much lower IFN-β responses to cytosolic DNA, which suggests the presence of additional DNA sensors in the innate immune system.

Direct biochemical approaches with immunoprecipitation assays and mass spectrometry have identified nucleic acid sensors in the DExD/H-box helicase superfamily in both plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs)21 and myeloid DCs (mDCs)22. In plasmacytoid DCs, DHX36 and DHX9 have been identified as cytosolic CpG-DNA sensors that pair with the adaptor MyD88 to trigger type I interferon responses21. In mDCs, a three-helicase DDX1-DDX21-DHX36 complex has been identified as a sensor of the synthetic RNA duplex poly(I:C) in the cytosol that pairs with the adaptor TRIF to trigger type I interferon responses22. Those data prompted us to undertake a bioinformatics analysis in which we identified 59 members of the DExD/H-box helicase superfamily, including the RIG-I-like receptor subfamily (RIG-I, Mda5 and LGP-2). We therefore hypothesized that the DExD/H-box helicase superfamily may be more important in sensing microbial nucleic acids than previously thought.

RESULTS

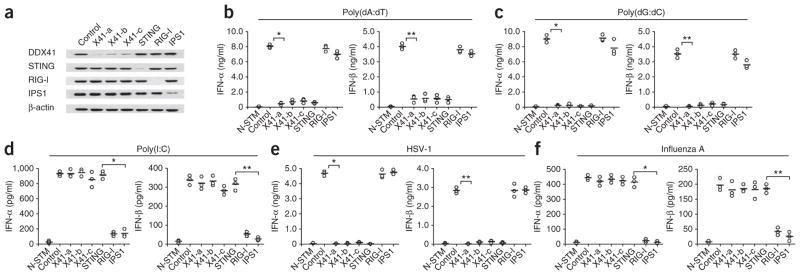

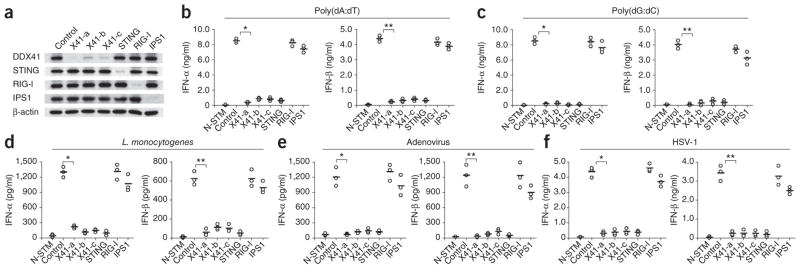

The helicase DDX41 senses B-form in mDCs

By screening all 59 members of the DExD/H family of helicases through the use of small interfering RNA (siRNA), we found that knocking down expression of the helicase DDX41 in the mouse splenic mDC line D2SC led to over 90% lower IFN-β responses to poly(dA:dT) delivered via lipofection (data not shown). We confirmed those data by stable knockdown of DDX41 expression through the use of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in this mDC line. Three distinct DDX41-targeting shRNA constructs efficiently knocked down expression of DDX41 protein without affecting the expression of STING, RIG-I or IPS-1 (Fig. 1a). Likewise, targeting STING, RIG-I or IPS-1 with shRNA specifically knocked down expression of the targeted protein without altering the expression of untargeted proteins. When stimulated with B-form DNA delivered via lipofection, D2SC mDCs in which RIG-I or IPS-1 was knocked down produced abundant IFN-α and IFN-β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), whereas these cytokine responses were considerably attenuated in D2SC cells in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). In contrast, the production of IL-1β in response to B-form DNA, which is dependent on AIM2 (refs. 10–15), was not affected by knockdown of DDX41 or STING in D2SC mDCs (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We next investigated whether DDX41 also has a role in sensing poly(dG:dC) in D2SC mDCs. We found that knocking down DDX41 or STING resulted in over 98% less production of IFN-α, IFN-β and IL-6 and over 80% less production of TNF by mDCs in response to poly(dG:dC) delivered via lipofection (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1b). In contrast, knocking down RIG-I or IPS-1 had no effect on the production of these cytokines. Although knockdown of DDX41 or STING had little effect on the production of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-6 or TNF by D2SC mDCs in response to poly(I:C), knockdown of RIG-I or IPS-1 led to attenuated cytokine responses to poly(I:C) by D2SC mDCs (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1c). These data suggest specificity for DDX41 and STING in the response to cytosolic DNA.

Figure 1.

DDX41 senses cytosolic DNA in mDCs. (a) Immunoblot analysis of the knockdown efficiency of nontargeting scrambled shRNA (Control) or shRNA targeting mRNA encoding DDX41 (three shRNAs: X41-a, X41-b and X41-c), STING, RIG-I or IPS1 (above lanes) in D2SC mDCs; β-actin (bottom) serves as a loading control throughout. (b–f) ELISA of IFN-α and IFN-β in D2SC cells either treated with scrambled shRNA and left unstimulated (N-STM) or treated with scrambled shRNA (Control) or shRNA targeting mRNA encoding DDX41, STING, RIG-I or IPS1 (as in a; horizontal axis), then stimulated for 16 h with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml; b), poly(dG:dC) (1 μg/ml; c), poly(I:C) (2.5 μg/ml; d), HSV-1 (multiplicity of infection (MOI), 10; e) or influenza A virus (MOI, 10; f). Each symbol represents the result of one experiment; small horizontal lines indicate the average. (b) *P < 1.5 × 10−6 and **P < 3.5 × 10−5; (c) *P < 8.3 × 10−6 and **P < 2.8 × 10−5; (d) *P < 5.2 × 10−5 and **P < 9.5 × 10−5; (e) *P < 8.10 × 10−7 and **P < 6.0 × 10−6; and (f) *P < 3.2 × 10−5 and **P < 2.0 × 10−4 (Student’s t-test). Data are from at least three independent experiments.

DDX41 senses DNA virus in mDCs

To determine whether DDX41 has a role in sensing viral infection, we knocked down DDX41, STING, RIG-I or IPS-1 in D2SC mDCs and cultured the cells with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1; Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1d) or influenza A virus (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1e). The results of quantitative PCR analysis of HSV-1 DNA indicated that the cells were cultured with equivalent amounts of virus (Supplementary Fig. 1f). D2SC mDCs in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down lost the ability to produce large amounts of type I interferon, IL-6 or TNF in response to HSV-1 (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1d) but had normal cytokine responses to influenza A virus (Fig. 1e and Supplementary 1e). D2SC mDCs in which RIG-I or IPS-1 was knocked down had normal cytokine responses to HSV-1 (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1d) but had much lower responses to influenza A virus (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1e). Control D2SC mDCs treated with scrambled shRNA had normal cytokine responses to both HSV-1 and influenza A virus (Fig. 1e,f and Supplementary Fig. 1d,e). To determine whether DDX41 has an important role in antiviral defense, we measured the replication of HSV-1 DNA in the cells by quantitative PCR. The replication of HSV-1 was much greater in D2SC mDCs in which DDX41 was knocked down (Supplementary Fig. 1g), which indicated an important role for DDX41 in suppressing infection with DNA viruses. Although DHX9 and DHX36 sense cytosolic CpG DNA in plasmacytoid DCs21, D2SC mDCs in which DHX9 or DHX36 was knocked down had normal cytokine responses to B-form DNA (Supplementary Fig. 1h,i), which indicated that these two helicases have no role in sensing B-form DNA in mDCs.

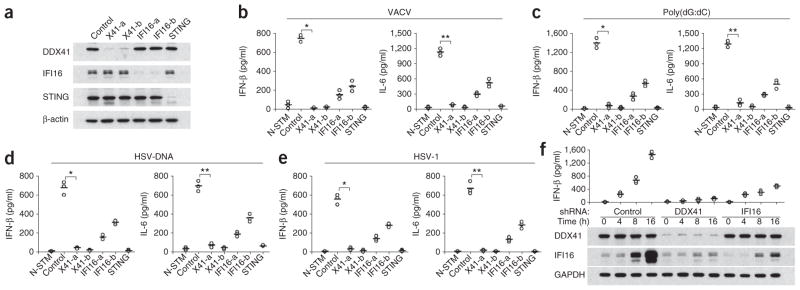

DDX41 senses cytosolic DNA in bone marrow–derived DCs

To determine whether the DDX41 senses cytosolic DNA in primary cells, we prepared mDCs derived from bone marrow with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and treated these bone marrow–derived DCs (BMDCs) with shRNA targeting DDX41, STING, RIG-I or IPS-1. We then assessed the specificity and efficiency with which the expression of DDX41, STING, RIG-I or IPS-1 protein was knocked down through the use of shRNA in the BMDCs (Fig. 2a). We stimulated those BMDCs with poly(dA:dT), poly(dG:dC), Listeria monocytogenes, adenovirus, HSV-1, poly(I:C) or influenza A virus and measured IFN-α and IFN-β in the culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). BMDCs in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down had lower IFN-α and IFN-β responses to poly(dA:dT), poly(dG: dC), L. monocytogenes, adenovirus and HSV-1 than did BMDCs treated with scrambled shRNA (Fig. 2b–f). BMDCs in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down produced normal amounts of IFN-α and IFN-β in response to poly(I:C) or influenza A virus (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, BMDCs in which RIG-I or IPS-1 was knocked down produced normal amounts of IFN-α and IFN-β in response to DNA itself or DNA virus and produced much less IFN-α and IFN-β in response to poly(I:C) or influenza A virus. These results confirmed published studies showing that RIG-I and IPS-1 have important roles in sensing poly(I:C) and influenza A virus but they are not involved in sensing DNA itself or DNA virus in mDCs8,9. To determine whether DDX41 regulates the expression of interferon-inducible genes, we compared the mRNA expression profiles of BMDCs in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down or BMDCs treated with scrambled shRNA after activation with poly(dA:dT). Knockdown of DDX41 or STING prevented the induction of type I interferon–induced gene expression activated by the poly(dA:dT) (Supplementary Table 1). These data indicate that DDX41 has a critical role in sensing DNA in BMDCs and that STING functions downstream of DDX41 as a key adaptor molecule for signaling.

Figure 2.

Knockdown of DDX41 or STING in BMDCs abolishes their cytokine responses to DNA alone and DNA viruses. (a) Immunoblot analysis of the knockdown efficiency of shRNA (as in Fig. 1a) in BMDCs. (b–f) ELISA (as in Fig. 1a) of IFN-α and IFN-β in DCs either treated with scrambled shRNA and left unstimulated or treated with scrambled shRNA or shRNA (as in a), then stimulated for 16 h with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml; b), poly(dG:dC) (1 μg/ml; c), L. monocytogenes (20 colony-forming units; d), adenovirus (MOI, 10; e) or HSV-1 (MOI, 10; f). (b) *P < 8.3 × 10−7 and **P < 4.0 × 10−6; (c) *P < 6.0 × 10−6 and **P < 1.8 × 10−5; (d) *P < 5.7 × 10−5 and **P < 2.5 × 10−4; (e) *P < 4.4 × 10−4 and **P < 6.4 × 10−4; and (f) *P < 3.4 × 10−5 and **P < 1.9 × 10−4 (Student’s t-test). Data are from at least three independent experiments.

DDX41 senses DNA viruses and DNA in human monocytes

A published study has identified IFI16 as a sensor of DNA in human monocytes through the use of a biotin-labeled vaccinia virus DNA-precipitation method20. To determine whether the human DDX41 senses viral DNA in human monocytes, we treated THP-1 cells, a human monocyte cell line, with shRNA targeting DDX41, IFI16 or STING and confirmed that expression of the targeted protein was knocked down (Fig. 3a). After knockdown of DDX41, IFI16 or STING in THP-1 cells, we stimulated the cells with vaccinia virus DNA, HSV-1 DNA, poly(dG:dC) or HSV-1 and measured IFN-β and IL-6 in the culture supernatants by ELISA. Knockdown of DDX41 or STING in THP-1 cells eliminated the ability to produce large amounts of IFN-β and IL-6 in response to DNA or HSV-1 (Fig. 3b–e). However, knockdown of IFI16 in THP-1 cells led to slightly lower responses of IFN-β and IL-6 to DNA or HSV-1, which confirmed the results of a published study showing that IFI16 has a moderate role in viral DNA sensing20.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of DDX41 or STING in THP-1 cells abolishes their cytokine responses to DNA or HSV-1. (a) Immunoblot analysis of the knockdown efficiency of scrambled shRNA or shRNA targeting mRNA encoding DDX41 (two shRNAs: X41-a and X41-b), IFI16 (two shRNAs: IFI16-a and IFI16-b) or STING (above lanes ) in THP-1 cells. (b–e) ELISA (as in Fig. 1a) of IFN-β and IL-6 in THP-1 cells either treated with nontargeting scrambled shRNA and left unstimulated or treated with shRNA (as in a), then stimulated for 16 h with vaccinia virus (VACV) DNA (1 μg/ml; b), poly(dG:dC) (1 μg/ml; c), HSV DNA (1 μg/ml; d) or HSV-1 (MOI, 10; e). (b) *P < 4.0 × 10−6 and **P < 2.0 × 10−5; (c) *P < 3.6 × 10−5 and **P < 2.2 × 10−5; (d) *P < 9.3 × 10−5 and **P < 5.10 × 10−5; (e) *P < 7.0 × 10−5 and **P < 7.8 × 10−5 (Student’s t-test). (f) ELISA of IFN-β (as in Fig. 1a; top) and immunoblot analysis of the expression of DDX41 and IFI16 (below) in THP-1 cells treated with nontargeting shRNA or shRNA targeting DDX41 or IFI16 and stimulated for 0–16 h with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml). GAPDH (glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase) serves as a loading control (bottom). Data are from at least three independent experiments.

To clarify the overlapping functions of DDX41 and IFI16, we assessed the expression profiles of DDX41, IFI16 and IFN-β in THP-1 cells. Although DDX41 was constitutively expressed in THP-1 cells, IFI16 was induced mainly after activation with poly(dA:dT) (Fig. 3f). We detected substantial induction of IFN-β after 4 h of stimulation, whereas we detected induction of IFI16 after 8 h of stimulation. Although knockdown of DDX41 blocked the induction of IFI16 after stimulation with poly(dA:dT), knockdown of IFI16 had no effect on DDX41 expression. These data indicate that DDX41 is more important than IFI16 in the initial sensing of B-form DNA and in triggering the early burst of the type I interferon response.

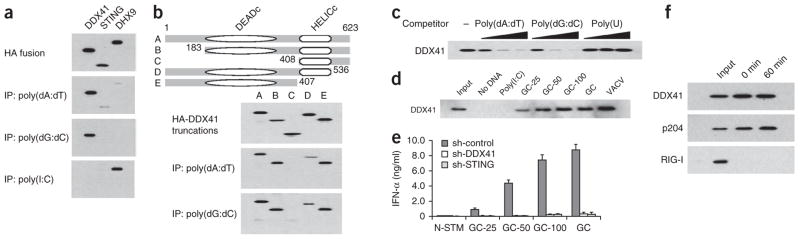

DDX41 binds DNA through a DEADc domain

To determine whether DDX41 directly binds DNA, we transfected HEK293T human embryonic kidney cells with plasmid encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged DDX41, STING or DHX9 recombinant protein, followed by purification with beads linked to antibody to HA (anti-HA). We incubated each purified helicase with biotin-labeled poly(dA:dT), poly(dG:dC) or poly(I:C), followed by the addition of avidin beads. Only recombinant DDX41 was immunoprecipitated by avidin beads plus poly(dA:dT) or poly(dG:dC) (Fig. 4a), which indicated that DDX41 bound DNA directly. To further determine whether DDX41 bound bacterial DNA in the infected cells, we analyzed L. monocytogenes–infected BMDCs by chromatin immunoprecipitation. These data showed that DDX41 directly bound the L. monocytogenes gene encoding phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (Supplementary Fig. 3a). To map the DNA-binding site of DDX41, we prepared truncated versions of DDX41 that we then tested in immunoprecipitation experiments with biotin-labeled DNA. The results of these experiments indicated that the DEADc (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) domain of DDX41 bound poly(dA:dT) and poly(dG:dC) (Fig. 4b). To determine the binding specificity of DDX41, we did immunoprecipitation competition experiments with increasing amounts of unlabeled poly(dA:dT), poly(dG:dC) or poly(U). We found that only unlabeled DNA blocked the binding of biotin-labeled DNA to DDX41 (Fig. 4c). To exclude the possibility that DDX41-containing samples purified from HEK293T cells contained other DNA-binding proteins that mediated the interaction between DDX41 and DNA, we expressed histidine-tagged full-length DDX41 or DDX41 with deletion of the DNA-binding domain in Escherichia coli, purified the tagged proteins and assessed them in immunoprecipitation experiments with biotin-labeled poly(dA:dT) (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Only histidine-tagged full-length DDX41 bound poly(dA:dT) (Supplementary Fig. 3c), which indicated that DDX41 binds DNA through the DEADc domain. To determine whether the binding of DDX41 to DNA substrates was dependent on nucleotide composition or length, we used biotin-labeled vaccinia virus DNA or poly(dG:dC) of various lengths to immunoprecipitate purified HA-tagged DDX41 protein. Vaccinia virus DNA and poly(dG:dC) of various lengths precipitated DDX41 (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, poly(dG:dC) 25, 50 or 100 nucleotides in length was able to activate an interferon response in D2SC cells (Fig. 4d). This response was substantially attenuated by knockdown of DDX41 or STING (Fig. 4e). To determine whether stimulation with DNA modified the binding activity of endogenous DDX41, we incubated D2SC cells for 0 or 60 min with biotin-labeled poly(dA:dT). We prepared whole-cell lysates from the treated D2SC cells and subjected the lysates to precipitation with avidin-conjugated beads. We detected proteins bound to biotin-labeled poly(dA:dT) with antibody to DDX41, p204 (the mouse ortholog of IFI16) or RIG-I. We constitutively detected the DDX41-DNA complex in mDCs (Fig. 4f). Unlike the gene encoding p204, the gene encoding DDX41 was not interferon inducible (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

DDX41 interacts with DNA but not with RNA. (a) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation (IP) assays of purified HA-tagged DDX41, STING or DHX9 incubated with biotinylated poly(dA:dT), poly(dG:dC) or poly(I:C), probed with anti-HA. (b) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation assays of purified HA-tagged full-length DDX41 (A) and serial truncations of DDX41 (B–E) incubated individually with biotinylated DNA, probed with anti-HA. Top, full-length and serial truncations of DDX41. DEADc, Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp motif; HELICc, helicase C-terminal domain; numbers indicate positions of amino acids. (c) Immunoblot analysis of nucleic acid–immunoprecipitation competition assays of increasing concentrations of DNA or poly(U) (0.5, 5 or 50 μg/ml; wedges) or no nucleic acid (−) added to a mixture of HA-tagged DDX41 plus biotinylated poly(dA:dT), probed with anti-HA. (d) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation assays of purified HA-tagged DDX41 incubated with avidin beads alone (No DNA) or with various biotinylated RNA or DNA substrates plus avidin beads, probed with anti-HA. Input, 10% of the purified HA-tagged DDX41; GC-25, GC-50 or GC-100, poly(dG:dC) 25, 50 or 100 nucleotides in length; GC, full-length poly(dG:dC); VACV, vaccinia virus. (e) ELISA of IFN-α in D2SC cells treated with control shRNA (sh-control) or shRNA targeting DDX41 (sh-DDX41) or STING (sh-STING) and left unstimulated (N-STM) or stimulated with poly(dG:dC) of various lengths (as in d). (f) Immunoblot analysis of endogenous DDX41, p204 and RIG-I in D2SC cells incubated for 0 or 60 min with biotinylated poly(dA:dT). Input, 10% of the D2SC lysate. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d. in e).

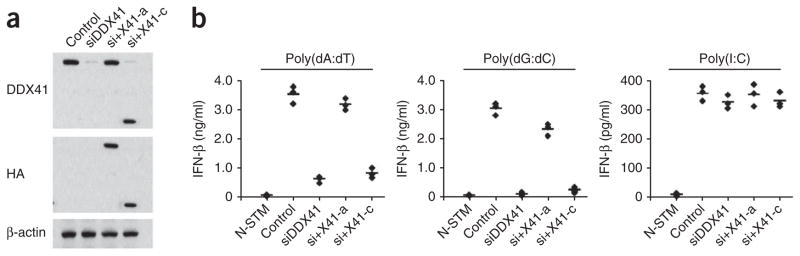

‘Rescue’ of the defect induced by DDX41-specific siRNA

To determine whether recombinant DDX41 was able to ‘rescue’ the defect in DNA-activated cytokine production caused by siRNA-mediated knockdown of DDX41, we individually expressed HA-tagged full-length or truncated DDX41 protein (lacking the DNA-binding domain) in D2SC cells in which DDX41 was knocked down through the use of siRNA (Fig. 5a). This siRNA selectively targeted the 3′ untranslated region of DDX41 mRNA. Therefore, only the expression of endogenous DDX41 was knocked down. Only full-length DDX41 was able to restore the IFN-β responses to both poly(dA:dT) and poly(dG:dC) (Fig. 5b). DDX41 with deletion of the DNA-binding domain failed to restore these responses. These data indicate that the DNA-binding activity of DDX41 is necessary for eliciting the interferon response to cytosolic DNA.

Figure 5.

Recombinant DDX41 can ‘rescue’ the defect in DNA-activated production of interferon caused by knockdown of DDX41 via siRNA. (a) Immunoblot analysis of endogenous DDX41 in D2SC mDCs (Control) or of recombinant HA-tagged full-length or truncated DDX41 in D2SC mDCs with selective knockdown of endogenous DDX41 alone (siDDX41) or along with expression of full-length DDX41 (si+X41-a) or DDX41 with deletion of the DNA-binding domain (si+X41-c). (b) ELISA (as in Fig. 1a) of IFN-β in D2SC mDCs either left untreated and unstimulated (N-STM) or treated as in a and stimulated for 16 h with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml), poly(dG:dC) (1 μg/ml) or poly(I:C) (2.5 μg/ml). Data are from at least three independent experiments.

Interaction of DDX41 with STING

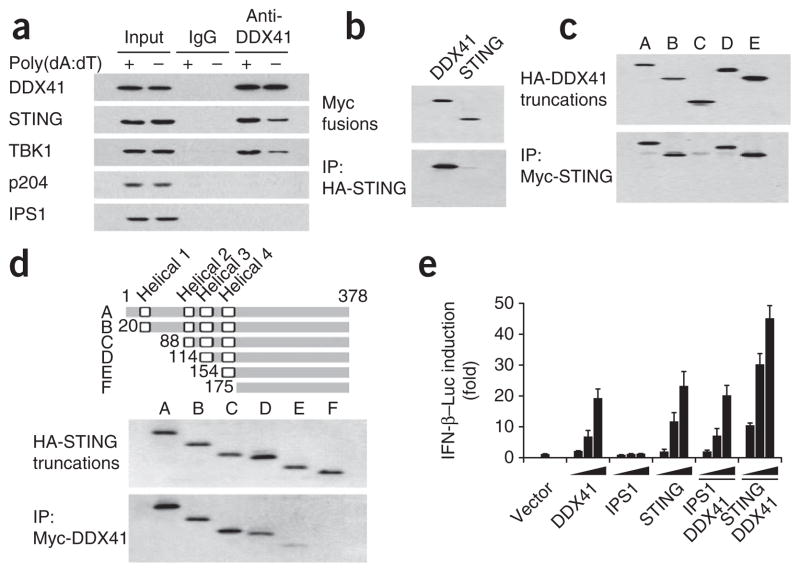

Because DDX41 and STING seemed to have a similar role in sensing DNA, we next investigated the potential interaction between DDX41 and STING in mDCs. We immunoprecipitated proteins from resting D2SC mDCs or poly(dA:dT)–activated D2SC mDCs with anti-DDX41. DDX41 precipitated endogenous amounts of STING and TBK1 in both resting D2SC mDCs and poly(dA:dT)–stimulated D2SC mDCs (Fig. 6a). In contrast, anti-DDX41 did not precipitate p204 or IPS-1. Notably, more STING and TBK1 were precipitated by anti-DDX41 in mDCs after stimulation with DNA (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Interaction of DDX41 with STING. (a) Immunoblot analysis of proteins (left margin) precipitated with anti-DDX41 or immunoglobulin G (IgG; control) from whole-cell lysates of D2SC cells left unstimulated (−) or stimulated with poly(dA:dT) (+). Input, 10% of the D2SC cells lysate. (b) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation assays of purified HA-tagged STING incubated with Myc-tagged DDX41 or STING, probed with anti-Myc. (c) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation assays of purified HA-tagged full-length or truncated DDX41 (as in Fig. 4b) incubated with Myc-tagged STING, probed with anti-HA. (d) Immunoblot analysis of purified HA-tagged full-length STING (A) or truncated STING (B–F), probed with anti-HA (middle), and immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation assays of HA-tagged STING (as above) incubated with Myc-tagged DDX41, probed with anti-HA (bottom). Top, full-length STING (A) and serial truncations of STING (B–F); numbers indicate positions of amino acids. (e) Activation of the Ifnb promoter in mouse L929 cells transfected with an IFN-β luciferase reporter (IFN-β–Luc; 100 ng) plus increasing concentrations (20, 100 or 200 ng; wedges) of expression vectors for DDX41, IPS1 or STING individually; or expression vector for DDX41 (20 ng; solid bar) together with increasing concentrations (20, 100 or 200 ng; wedges) of expression vectors for IPS1 or STING. Results are presented relative to those of cells transfected with empty vector alone (Vector). Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d. in e).

To map the STING-binding sites of DDX41, we incubated recombinant HA-tagged STING with purified recombinant Myc-tagged DDX41 or STING, followed by precipitation with anti-HA beads. We found that recombinant DDX41 bound to recombinant STING (Fig. 6b). Immunoprecipitation of Myc-tagged STING showed that the DEADc domain of DDX41 bound STING (Fig. 6c). Likewise, we prepared truncated versions of STING and assayed them by immunoprecipitation to identify the DDX41-binding site of STING. We found that the region spanning the second to fourth transmembrane domains of STING interacted with DDX41 (Fig. 6d).

DDX41 and STING facilitate interferon induction

To further confirm the role of DDX41 in sensing cytosolic DNA, we overexpressed DDX41 or STING in the mouse fibroblast cell line L929 containing a luciferase reporter linked to the Ifnb promoter. We found that overexpression of DDX41 or STING led to more activation of the Ifnb promoter in L929 cells. Transfection of L929 cells with 20 ng of expression vector for DDX41 or STING led to twofold more activation of the Ifnb promoter (Fig. 6e). In contrast, overexpression of IPS-1 did not result in more activation of the Ifnb promoter in L929 cells, although overexpression of IPS-1 led to such activation in HEK293T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). Notably, overexpression of both DDX41 and STING together had a synergistic effect in promoting activity of the Ifnb promoter (Fig. 6e).

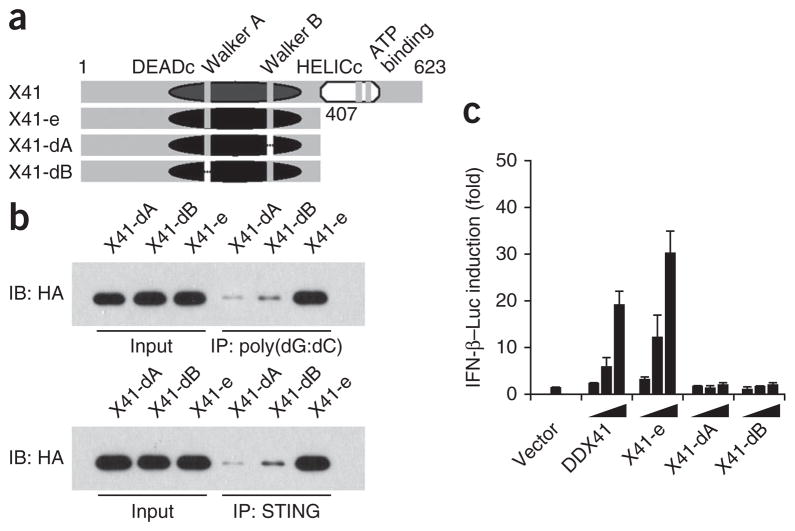

The Walker motifs in DDX41 are essential to sense DNA

To determine whether the Walker A or Walker B motif in DDX41 was required for binding DNA, we prepared HA-tagged DDX41 mutants with deletion of the Walker A or Walker B motif and analyzed these in immunoprecipitation experiments with biotin-labeled poly(dG:dC) or Myc-tagged STING (Fig. 7a). The results of these assays indicated that the DEADc domain of DDX41 without the Walker A motif or without the Walker B motif did not bind DNA or STING (Fig. 7b). To further confirm the role of these motifs in the sensing of DNA by DDX41, we overexpressed full-length or mutant DDX41 in the L929 Ifnb luciferase reporter cell line described above. We found that overexpression of mutant DDX41 without the Walker A motif or without the Walker B motif was not able to activate the Ifnb promoter. Notably, overexpression of DDX41 lacking the HELICc domain led to more activation of the Ifnb promoter than did expression of full-length DDX41 (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

The Walker motifs in DDX41 are essential for sensing DNA. (a) Full-length DDX41 (X41) and serial deletion mutants of DDX41 lacking the HELICc domain (X41-e), both the Walker A motif and the HELICc domain (X41-dA) or both the Walker B motif and the HELICc domain (X41-dM). (b) Immunoblot analysis of immunoprecipitation assays of purified HA-tagged DDX41 (as in a) incubated with biotinylated poly(dG:dC) followed by addition of avidin beads (top), or with Myc-tagged STING, followed by the addition of anti-Myc beads (bottom), probed with anti-HA. Input, 10% of the purified HA-tagged DDX41. (c) Activation of the Ifnb promoter in L929 cells transfected with the IFN-β luciferase reporter (100 ng) plus increasing concentrations (20, 100 or 200 ng; wedges) of expression vectors for DDX41 (as in a); a renilla luciferase reporter (2 ng) was transfected simultaneously as an internal control. Results are presented relative to those of cells transfected with empty vector alone (Vector). Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean and s.d. in c).

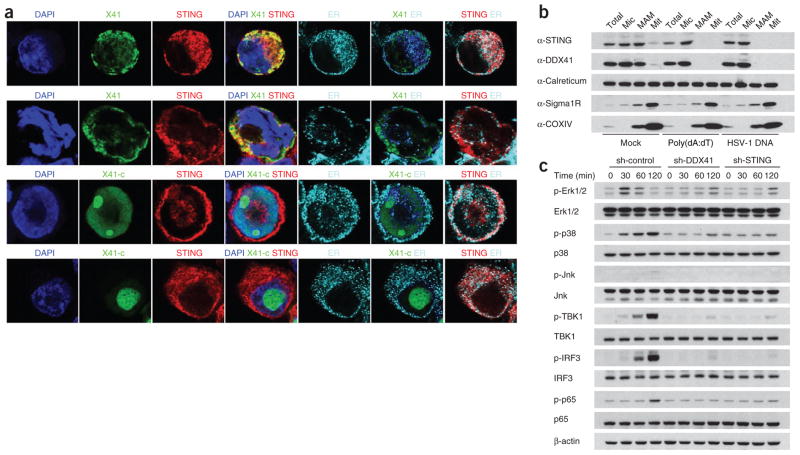

DDX41 localizes together with STING in the cytosol

Because anti-DDX41 and anti-STING for cell staining are not available, we expressed HA-tagged DDX41 together with Myc-tagged STING in HEK293T cells to visualize their subcellular localization. DDX41 and STING did not localize together with nuclear staining; instead, DDX41 localized together with STING and the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 8a, top row), which suggested that the DDX41-STING complex was located in the cytosol. Furthermore, after stimulation with poly(dA:dT), there was lower expression of DDX41 and STING in the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria and higher expression of DDX41 and STING in endosomes identified by staining for the early endosome marker TfR and late endosome marker LAMP-1 (Fig. 8a, second row, and Supplementary Fig. 6a,b), which confirmed a similar published observation18,19. In contrast, the DDX41 mutant lacking the STING-binding site did not localize together with STING (Fig. 8a, third and bottom rows). Fractionation analysis subsequently demonstrated that DDX41 and STING fractionated together with microsome fractions, mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane fractions and mitochondria fractions in D2SC cells under unstimulated conditions (Fig. 8b). After stimulation with DNA, DDX41 and STING associated mostly with microsome fractions.

Figure 8.

STING is the key adaptor for DDX41 signaling. (a) Confocal microscopy of HEK293T cells transfected with expression plasmid for HA-tagged STING, Myc-tagged DDX41 (X41) and/or Myc-tagged DDX41 with truncation of the C terminus (X41-c), then left unstimulated (top and third rows) or stimulated for 4 h with poly(dA:dT) (second and bottom rows). Nuclei are stained with the DNA-intercalating dye DAPI; staining of calreticulin serves as a marker of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Original magnification, ×100. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (b) Immunoblot analysis of the fractionation of unstimulated D2SC cells (Mock) or D2SC cells stimulated with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml) or HSV-1 DNA (1 μg/ml), probed with anti- STING, anti-DDX41, anti-calreticulin (to detect the endoplasmic reticulum), anti-Sigma1R (to detect the mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM)) or anti-COXIV (to detect mitochondria (Mit)). Total, 15% of the D2SC lysate; Mic, microsome. Data are representative of three experiments. (c) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated (p-) and total Erk1/2, p38, Jnk, TBK1, IRF3 and p65 in lysates of BMDCs treated with shRNA (as in Fig. 4e) and stimulated for 0–120 min with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml). Data are representative of three experiments.

DNA triggers downstream signaling through DDX41

It has been shown that overexpression of STING in HEK293T cells results in robust activation of the promoters of Ifnb, Irf3 (which encodes the transcription factor IRF3) and Nfkb1 (which encodes the p50 subunit of transcription factor NF-κB)18. We investigated whether downstream signaling by DDX41 and STING in BMDCs induced by cytosolic poly(dA:dT) or poly(dG:dC) DNA involves mitogen-activated protein kinases and activation of NF-κB and IRF3. Using control BMDCs and BMDCs in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down, we stimulated cells with poly(dA:dT), prepared total cell extracts and analyzed them by immunoblot (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Fig. 7). In control BMDCs, we detected phosphorylation of the kinases Erk1/2, p38 and TBK1 and the p65 subunit of NF-κB and IRF3 at 60–120 min after DNA stimulation. In contrast, phosphorylation of Erk1/2, p38, TBK1, p65 and IRF3 was barely detectable in BMDCs in which DDX41 or STING was knocked down. Furthermore, we observed that stimulation with cytosolic DNA did not activate phosphorylation of the kinase Jnk. These data suggest that DDX41 and STING are required for activation of intracellular mitogen-activated protein kinases, NF-κB and interferon-response signal-transduction pathways after stimulation with cytosolic DNA.

DISCUSSION

Published studies have identified three molecular sensors for cytosolic DNA: DAI23, RNA polymerase III8,9 and IFI16 (ref. 20). However, cells derived from DAI-deficient mice respond normally to B-form DNA and infection with DNA viruses24,25. In addition, the ability of RNA polymerase III to sense cytosolic DNA is dependent on RIG-I and IPS-1 in HEK293T cells8,9, and IPS-1- deficient mice have normal cytokine production in response to DNA26,27. A human hepatoma cell line (Huh-7.5.1) that does not express functional RIG-I still has cytokine responses to HSV-1 (ref. 28). Although IFI16 has been shown to use STING for sensing cytosolic DNA, knockdown of IFI16 only led to slightly lower IFN-β responses to cytosolic DNA, whereas knockdown of STING led to a more complete blockade of such responses. Collectively, these results suggest the presence of additional DNA sensors in the innate immune system.

Two additional sensors for DNA and/or RNA in the DExD/H-box helicase superfamily have been identified by immunoprecipitation of DNA or RNA and mass spectrometry. That, together with the fact that RIG-I, Mda5 and LGP2 belong to a subfamily of the DExD/H-box helicase superfamily, suggests that helicases may have a much broader role in sensing nucleic acids than previously appreciated. By siRNA screening of all 59 helicases, we have now identified DDX41 as an additional sensor of cytosolic DNA in mDCs with an important role in sensing DNA viruses, such as HSV-1 and adenovirus, but not RNA viruses, such as influenza A virus. DDX41 directly bound DNA and STING via its DEADc domain and triggered signaling by mitogen-activated protein kinases, TBK1, NF-κB and IRF3 in mDCs.

Our study has also suggested that DDX41 and IFI16 may have complementary roles in sensing cytosolic DNA. Although DDX41 was constitutively expressed in THP-1 cells, IFI16 was induced by stimulation with DNA. Furthermore, DDX41 formed a complex with STING in the steady state, and IFN-β was induced earlier than IFI16 in THP-1 cells, which suggests that DDX41 has a more important role than IFI16 in the initial sensing of microbial DNA and in triggering the early burst of the type I interferon response. This initial type I interferon response upregulated IFI16, which has a more important role in the amplification phase of the type I interferon response to cytosolic DNA. In eukaryotes, there is a total of 59 DExD/H helicases. The evolutionary pressure for survival after viral infection has led to a highly redundant antiviral system in the innate immune system that uses multiple sensors for the same nucleic acids, with different helicases to sense different forms of nucleic acids, and other different helicases as antiviral sensors in different cell types.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

Primary bone marrow was collected from C57BL/6 mice for the generation of BMDCs. Animals were housed in specific pathogen–free barrier facilities. All experiments were according to institutional guidelines of UT MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Reagents

Vaccinia virus DNA and HSV-1 DNA (sequences as published20), poly(dA:dT) and poly(dG:dC) DNA were from Sigma. Poly(I:C) (low molecular weight; 0.2–1 kilobases) was from Invivogen. Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen. The following antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis and/or immunoprecipitation: anti-DDX41 (H00051428; Novus Biologicals); anti-STING (LS-C108557; Life Span); antibody to phosphorylated p65 (3033), p38 (4631), IRF3 (4947), Jnk (9251), Erk (4377) or TBK1 (5483), anti-p65 (4764), anti-p38 (9212), anti-Jnk (9252), anti-Erk (4695), anti-TBK1 (3504), Alexa Fluor 555–Myc (2279) and Alexa Fluor 488–HA (2350; all from Cell Signaling); horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-HA (ab1265) and anti-Myc (ab62928), and anti-histidine (ab1187; all from Abcam); and anti-IRF3 (FL-425; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

D2SC cell culture and lentiviral infection

D2SC cells were maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FCS and 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen-Gibco). D2SC cells were infected with the pLKO.1 lentivirus vector carrying a target gene sequence or scrambled shRNA (Open Biosystems). Cells were selected by the addition of puromycin (2 ng/ml) to the medium 24 h after infection, then were stimulated for 16 h with DNA (1 μg/ml) or poly(I:C) (2.5 μg/ml) delivered via Lipofectamine 2000, or with HSV-1 or influenza A virus, each at an MOI of 10.

In vitro culture of BMDCs

Single-cell suspensions of bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, HEPES, pH 7.3, penicillin, streptomycin and β-mercaptoethanol, supplemented with mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 20 ng/ml; R&D Systems). Fresh GM-CSF was provided on days 3 and 5 of culture. Cells recovered on day 6 were used for shRNA-mediated knockdown and were stimulated with DNA 36 h after treatment with shRNA. Knockdown efficiency was detected by immunoblot analysis. GM-CSF-derived BMDCs recovered on day 7 of culture were left unstimulated or stimulated for 16 h with DNA, L. monocytogenes, HSV-1 or adenovirus. For analysis of interferon-inducible gene expression, GM-CSF-derived BMDCs were recovered on day 7, mRNA was isolated from cells without stimulation or after stimulation for 8 h with poly(dA:dT), and the abundance of mRNA was detected by real-time RT-PCR.

THP-1 cell culture and lentiviral infection

THP-1 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FCS and 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen-Gibco). THP-1 cells were infected with a pLKO.1 lentivirus vector carrying a target gene sequence or scrambled shRNA (Open Biosystems). After 24 h of culture, cells were selected by the addition of puromycin (2 ng/ml) to the medium. Cells were stimulated with DNA (1 μg/ml) delivered by Lipofectamine 2000 or with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10. Knockdown efficiency was detected by immunoblot analysis.

Measurement of cytokine production

Mouse D2SC mDCs or human THP-1 cells infected with shRNA-expressing lentivirus vectors were cultured with DNA (1 μg/ml) or poly(I:C) (2.5 μg/ml) delivered by Lipofectamine 2000 or with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10. The concentration of IFN-α, IFN-β, IL-6 and TNF in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA (IFN-α and IFN-β, PBL InterferonSource; IL-6 and TNF, R&D Systems).

IFN-β luciferase reporter assay

L929 cells were seeded on 48-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well) and then transfected with 100 ng IFN-β–luciferase reporter vector and 2 ng renilla-luciferase reporter vector with increasing amounts (20, 200 or 200 ng) of expression vectors for DDX41, STING or IPS-1 individually or 20 ng DDX41 expression vector plus increasing amounts (20, 100 or 200 ng) of expression vector for IPS-1 or STING. Empty control vector was added so that a total of 500 ng vector DNA was transfected into each well. At 30 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml) delivered by Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were collected after 6 h of stimulation. Luciferase activity in total cell lysates was detected with a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega).

In vitro immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

Lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged proteins were incubated with anti-HA beads (Sigma) and proteins were eluted from beads. For precipitation with NeutrAvidin beads (Pierce), purified proteins were incubated for 2 h with biotin-labeled DNA or RNA. After incubation with NeutrAvidin beads, bound complexes were pelleted by centrifugation and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-HA. For confirmation of DDX41 binding specificity, immunoprecipitation assays were repeated in the presence or absence of increasing amounts (0.5, 5 or 50 μg/ml) of unlabeled DNA or poly(U). For immunoprecipitation with anti-HA or anti-Myc beads, purified HA-tagged proteins were incubated for 1 h with purified Myc-tagged proteins. Beads were then added; after 1 h of incubation, bound complexes were pelleted by centrifugation. Proteins and beads were analyzed by immunoblot with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-HA or anti-Myc.

Confocal microscopy

HEK293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for HA-tagged STING and Myc-tagged DDX41. After 24 h, cells were fixed in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde and made permeable with 0.1% (vol/vol) saponin. Nonspecific receptors on cells were then blocked for 30 min with 10% (vol/vol) goat serum, followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated anti-Myc and Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-HA and confocal microscopy.

Fractionation

Fractionation was done as described19 for mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane, mitochondria and microsomes isolated from mouse D2SC mDCs. Cells were left unstimulated or were stimulated for 4 h with poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/ml) or HSV-1 DNA (1 μg/ml) delivered by Lipofectamine 2000, then were washed with PBS and resuspended in sucrose homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose and 10 mM HEPES, pH7.4). Cell lysates were then centrifuged and fractioned. Pellets of the fractions noted above were resuspended in mannitol buffer B (0.225 M mannitol, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.3 and 1 mM EDTA).

Signal transduction

BMDCs were stimulated for 0, 30, 60 and 120 min with poly(dA:dT) and then lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS). Lysates were resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test.

Additional methods

Information on the expression and purification of full-length and truncated DDX41 proteins, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and primers for mRNA assays and quantitative PCR and RNA-mediated interference is available in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Wentz and S. Watowich for critical reading; T. Zal for technical support with confocal microscopy; G. Cheng and K. Parvatiyar for suggestions on the experiments; and all colleagues in our laboratory.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Immunology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.Z. designed and did most of experiments; B.Y., M.B., N.L. and T.K. helped with experiments; and Y.-J.L. designed the research and supervised the project.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Recognition of viruses by innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasius AL, Beutler B. Intracellular toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2010;32:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato H, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myong S, et al. Cytosolic viral sensor RIG-I is a 5′-triphosphate-dependent translocase on double-stranded RNA. Science. 2009;323:1070–1074. doi: 10.1126/science.1168352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pippig DA, et al. The regulatory domain of the RIG-I family ATPase LGP2 senses double-stranded RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2014–2025. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu YH, Macmillan JB, Chen ZJ. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009;138:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ablasser A, et al. RIG-I-dependent sensing of poly(dA:dT) through the induction of an RNA polymerase III-transcribed RNA intermediate. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1065–1072. doi: 10.1038/ni.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts TL, et al. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science. 2009;323:1057–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hornung V, et al. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Datta JW, Wu PJ, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458:509–513. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bürckstümmer T, et al. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathinam VA, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandes-Alnemri T, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones JW, et al. Absent in melanoma 2 is required for innate immune recognition of Francisella tularensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9771–9776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003738107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong B, et al. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity. 2008;29:538–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 2009;461:788–792. doi: 10.1038/nature08476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unterholzner L, et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:997–1004. doi: 10.1038/ni.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim T, et al. Aspartate-glutamate-alanine-histidine box motif (DEAH)/RNA helicase A helicases sense microbial DNA in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15181–15186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z, et al. DDX1, DDX21 and DHX36 Helicases form a complex with the adaptor molecule TRIF to sense dsRNA in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2011;34:866–878. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takaoka A, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448:501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii KJ, et al. TANK-binding kinase-1 delineates innate and adaptive immune responses to DNA vaccines. Nature. 2008;451:725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature06537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, et al. Regulation of innate immune responses by DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) and other DNA-sensing molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5477–5482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801295105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Q, et al. The specific and essential role of MAVS in antiviral innate immune responses. Immunity. 2006;24:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar H, et al. Essential role of IPS-1 in innate immune responses against RNA viruses. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1795–1803. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng G, Zhong J, Chung J, Chisari FV. Double-stranded DNA and double-stranded RNA induce a common antiviral signaling pathway in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9035–9040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703285104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.