Abstract

Accumulating evidence indicates that activation of spinal cord microglia plays an important role in the genesis of neuropathic pain. Resolvin E1 (E1) is derived from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid and exhibits potent anti-inflammatory, pro-resolution, and anti-nociceptive effects. We further examined whether RvE1 could reduce neuropathic pain and modulate spinal cord microglial activation. Intrathecal pre-treatment of RvE1 (100 ng) daily for 3 days partially prevented the development of nerve injury-induced mechanical allodynia and up-regulation of IBA-1 (microglial marker) and TNF-α in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Furthermore, intrathecal post-treatment of RvE1 (100 ng), 3 weeks after nerve injury, transiently reduced mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia. Finally, RvE1 blocked lipopolisaccharide-induced microgliosis and TNF-α release in primary micoglial cultures. Our data suggest that RvE1 may attenuate neuropathic pain via inhibiting microglial signaling. Targeting the anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators may offer new options for preventing and treating neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), Tumor necrosis factor-alpha TNF-α, lipopolisacride (LPS), nerve injury, omega-3 poly unsaturated fatty acids, spinal cord

Introduction

Nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain, as results of diabetic neuropathy, viral infection, major surgeries, and chemotherapy, is becoming a major health problem worldwide (Costigan et al., 2009). Recent studies indicate a critical role of spinal cord microglia in the genesis of neuropathic pain (Tsuda et al., 2005;Suter et al., 2007). It is generally believed that microglial activation drives neuropathic pain via activation of microglial p38 MAP kinase and subsequent synthesis and release of the proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and growth factor (BDNF) to modulate spinal cord synaptic transmission and central sensitization (Ji and Suter, 2007;Coull et al., 2005;Kawasaki et al., 2008).

Accumulating evidence suggests that omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids-derived lipid mediators, such as resolvins, lipoxins, and neuroprotectins produce potent anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution actions in various animal models of inflammation (Serhan et al., 2008). Resolvin E1 (RvE1) is derived from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). We have recently shown that peripheral, spinal, or systemic administration of RvE1, at very low doses, reduced inflammatory pain, via inhibiting inflammation and transient receptor potential ion channel (TRPV1) (Xu et al., 2010). RvE1 elicits its antinociceptive effects via activation of the G-protein-coupled receptor ChemR23, which is widely expressed in immune cells (macrophages), neurons (primary sensory neurons and spinal cord neurons, and microglia (Ji et al., 2011). In the present study, we examined whether RvE1 would inhibit neuropathic pain by modulating microglial signaling.

Materials and methods

Animals and surgery

Adult CD1 mice (male, 25–35 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. All the animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Harvard Medical School. To produce chronic constriction injury, the left sciatic nerve was exposed at mid-thigh level under isoflurane anesthesia, and 3 loose silk ligatures (number 6 suture) were tied around the sciatic nerve and the incision was closed with sutures. To produce a spinal nerve ligation, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and the L6 transverse process was removed to expose the L4 and L5 spinal nerves. The L5 spinal nerve was then isolated and tightly ligated with 6-0 silk thread.

Drugs and administration

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was obtained from Sigma. RvE1 was kindly provided by Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals Inc. and prepared in PBS. For intrathecal injection, spinal cord puncture was made with a 30G needle between the L5 and L6 level to deliver reagents (10 μl) to the cerebral spinal fluid.

Primary cultures of microglia

Microglia cultures were prepared from cerebral cortexes of neonatal mice (P1-3). The cerebral hemispheres were isolated and transferred to ice-cold Hank’s buffer and the meninges were carefully removed. Tissues were then minced, triturated, filtered through a 100 μm nylon screen, and collected by centrifugation (3000g for 5 min). The cell pellets were broken with a pipette and resuspended in a medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in high glucose DMEM. After trituration, the cells were filtered through a 10 μm screen and grown on T75 flasks for three weeks. The medium was replaced twice a week. Twenty-four hours prior to the use, microglia were isolated by shaking and cultured in 12-well plates, at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/cm2.

ELISA

Mouse TNF-α ELISA kit was purchased from R&D. For in vitro experiments, microglial culture medium was collected after treatment. For in vivo experiments, mice were transcardially perfused with PBS after terminal anesthesia with isoflurane. Cells or spinal cord dorsal horn tissues were homogenized and protein concentrations were determined by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce). For each reaction in a 96-well plate, 100 μg of proteins were used, and ELISA was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol. The standard curve was included in each experiment.

Immunocytochemistry

Microglia cultures grown on glass coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and processed for immunofluorescence. The cultures were first blocked with 2% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with the IBA-1primary antibody (rabbit, 1:500, Wako) overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 h at room temperature with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:400, Jackson Immunoresearch). The stained cultures were examined with a Nikon fluorescence microscope, and images were captured with a CCD Spot camera. We determined different morphological activation states of microglia (microgliosis) as follows: control microglia were characterized as having thin stained cell bodies and few processes (often with two), whereas activated microglia cells were defined as having enlarged cell bodies with several projecting processes (Fig. 2A). Intermediate morphologies were excluded from the analysis when encountered.

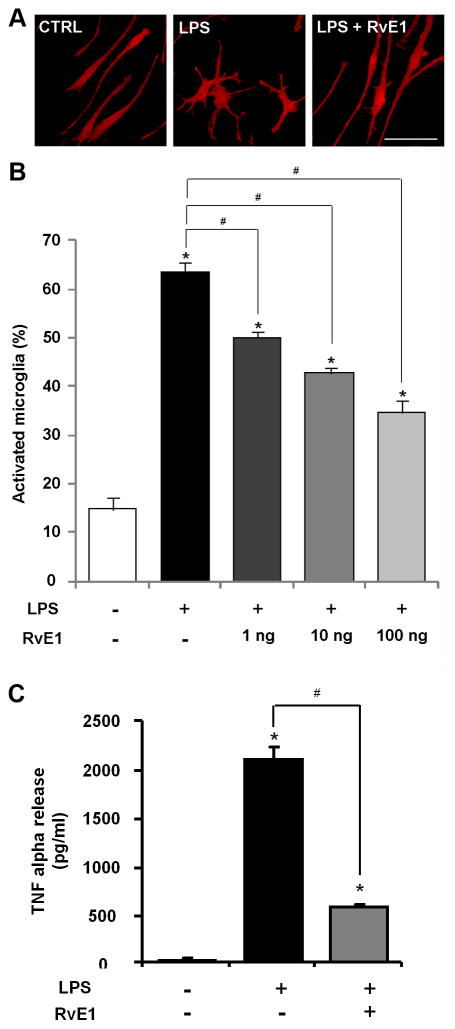

Figure 2. RvE1 inhibits LPS-induced microgliosis and TNF-α release in microglial cultures.

(A) IBA-1 immunostaining in control microglial cultures and cultures treated with LPS and RvE1/LPS. Scale, 10 μm. (B) Percentage of microglia with morphological changes (amoeboid). * P<0.05, compared to control, #P<0.05, compared to LPS. n=3 independent cover slips from 10 mice. LPS treatment (0.1 μg/ml) for 24 h induces marked microgliosis, which dose-dependently inhibited by RvE1 (100 ng/ml). (C) ELISA analysis shows that pre-treatment of microglial cultures with RvE1 (100 ng/ml), starting 15 min before LPS stimulation, inhibits LPS (0.1 μg/ml)-elicited TNF-α release. * P<0.05, compared to control, #P<0.05, compared to LPS. n=4 independent cultures from 10 mice.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Three days after CCI, spinal cord dorsal horn samples were collected from vehicle and RvE1-treated mice. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen). A total of 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using Omniscript reverse transcriptase. Sequences of the forward (F) and reverse (R) primers are:

IBA-1: GGACAGACTGCCAGCCTAAG (F), GACGGCAGATCCTCATCATT (R)

GFAP: GAATCGCTGGAGGAGGAGAT (F), GCCACTGCCTCGTATTGAGT (R)

GAPDH: TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG (F), CAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGA (R)

Quantitative PCR amplification reactions contained the same amount of reverse transcription (RT) product, 7.5 μl of 2× iQSYBR-green mix (BioRad) and 300 nM of primers in a final volume of 15 μl. The thermal cycling comprised of 3 min of polymerase activation at 95 °C, 45 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 95 °C, and 30 s annealing and extension at 60 °C, followed by a DNA melting curve for the determination of amplicon specificity. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Behavioral analysis

Animals were habituated to the testing environment daily for at least two days before baseline testing. For testing mechanical sensitivity, animals were put in boxes on an elevated metal mesh floor and allowed 30 min for habituation before examination. The plantar surface of each hindpaw was stimulated with a series of von Frey hairs with logarithmically incrementing stiffness (0.02–2.56 grams, Stoelting), presented perpendicular to the plantar surface. The 50% paw withdrawal threshold was determined using Dixon’s up-down method. For testing heat sensitivity, animals were put in plastic boxes and allowed 30 min for habituation before examination. Heat sensitivity was tested by radiant heat using Hargreaves apparatus (IITC Life Science Inc.).

Statistics

All data were expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between groups were compared using student t-test or ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test. The criterion for statistical significance was P<0.05.

Results

Spinal RvE1 treatment reduces nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain and spinal cord microglial activation

We first examined whether spinal (intrathecal) pretreatment of RvE1 (100 ng, daily for 3 days) would reduce nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve (CCI) elicited robust neuropathic pain behaviors in mice on day 3, including mechanical allodynia, a reduction of paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimulation (Fig. 1A), and heat hyperalgesia, a reduction in paw withdrawal latency in response to heat stimulation (Fig. 1B). Intrathecal pre-treatment of RvE1 reduced CCI-induced mechanical allodynia but not heat hyperalgesia, assessed 24 h after the last RvE1 injection (Fig. 1A, B).

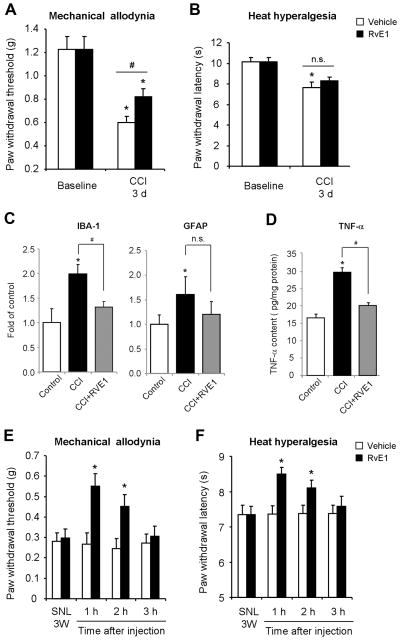

Figure 1. Spinal RvE1 treatment inhibits nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain symptoms and spinal microglial activation.

(A, B) Chronic nerve constriction (CCI)-induced mechanical allodynia (A) but not heat hyperalgesia (B) is reduced by RvE1 pre-treatment. RvE1 (100 ng, daily for 3 days) was given via intrathecal route, with the first injection starting 10 min before the nerve injury. Neuropathic pain behavior was tested 24 h after the last RvE1 injection. *P<0.05, compared to baseline, #P<0.05, compared to vehicle, n=5 mice from a single experiment. n.s., not significant. (C) Real-time RT-PCR analysis showing IBA-1 and GFAP mRNA levels in dorsal horn on post-CCI day 3. *P<0.05, compared to control (contralateral side), #P<0.05, compared to CCI. n.s., no significance. n=4 mice from a single experiment. (D) ELISA analysis showing TNF-α expression in the dorsal horn on post-CCI day 3. *P<0.05, compared to control, #P<0.05, compared to CCI. n=4 mice from a single experiment. (E, F) Spinal nerve ligation (SNL)-induced mechanical allodynia (E) and heat hyperalgesia (F) are reduced by intrathecal RvE1 post-treatment (100 ng, single injection), given 3 weeks after nerve injury. *P<0.05, compared to corresponding vehicle (PBS). n=5–6 mice from a single experiment.

To correlate neuropathic pain symptoms with microglia responses, we also examined whether the same RvE1 pre-treatment would suppress the CCI-induced expression of the microglial marker (IBA-1) and astrocytic marker (GFAP) in the spinal cord dorsal horn. RT-PCR analysis revealed that RvE1 pre-treatment prevented CCI-induced up-regulation of IBA-1 but not GFAP (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, ELISA analysis showed that the RvE1 pre-treatment prevented CCI-induced TNF-α expression in the dorsal horn (Fig. 1D).

We further examined whether RvE1 post-treatment could inhibit established neuropathic pain in the late-phase. To generate more persistent neuropathic pain, we produced another neuropathic pain model by spinal nerve ligation (SNL). SNL elicited marked mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia 3 weeks after nerve injury (Fig. 1E, F). Intrathecal administration of RvE1 (100 ng), 3 weeks after SNL, significantly reduced SNL-induced mechanical allodynia (Fig. 1E) and heat hyperalgesia (Fig. 1F). These anti-allodynic and anti-hyperalgesic effects were evident at 1 h, maintained at 2 h, but declined at 3 h following the RvE1 injection (Fig. 1E, F).

RvE1 inhibits LPS-induced microgliosis and TNF-α release in microglial cultures

Non-stimulated microglial cells in primary cultures exhibited thin cell bodies with long processes (often with two, Fig. 2A). Since TLR4 has been strongly implicated in spinal cord microglial activation and neuropathic pain (Tanga et al., 2005), we activated microglial cultures with the TLR4 agonist lipopolisaccharide (LPS). LPS treatment (0.1 μg/ml, 24 h) elicited marked microgliosis, and the activated microglia displayed enlarged cell bodies with short processes. The cell bodies of activated microglia become amoeboid (Fig. 2A). Notably, LPS-induced microgliosis was suppressed by RvE1, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). LPS (0.1 μg/ml, 3 h) also elicited a dramatic increase ( 100 fold) in TNF-α release, but this increase was largely prevented by RvE1 pre-treatment (100 ng/ml), starting 15 min before LPS stimulation (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that daily pre-treatment of RvE1 (100 ng, i.t.) for 3 days was effective in partially preventing CCI-induced mechanical allodynia (Fig. 1A). Given the fact that mechanical allodynia was tested 24 h after the last RvE1 treatment, RvE1 elicited enduring inhibition of mechanical allodynia (Fig. 1A). Of note the same pre-treatment also prevented CCI-induced up-regulation of the microglial marker IBA-1 (Fig. 1C) in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Furthermore, our in vitro study in primary cultures of microglia demonstrated a direct action of RvE1 on microglia, by inhibiting LPS-induced microgliosis (Fig. 2A,B). LPS is a ligand of TLR4, which is required for the nerve injury-induced spinal cord microglial activation and the development of neuropathic pain (Tanga et al., 2005). Since RvE1 pre-treatment inhibited microglial activation and mechanical allodynia but not heat hyperalgesia (Fig. 1A,B), spinal cord microglial activation after nerve injury should be associated with mechanical allodynia but not heat hyperalgesia.

RvE1 pre-treatment also prevented CCI-induced TNF-α up-regulation in the dorsal horn (Fig. 1D). In parallel, RvE1 treatment in vitro blocked LPS-induced TNF-α release in primary cultures of microglia (Fig. 2C). Given the facts that (1) microglia are a major source of TNF-α (Hanisch, 2002) and (2) TNF-α plays an important role in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain (Sommer and Kress, 2004) and induction of central sensitization (Park et al., 2011;Zhang et al., 2011), RvE1 is likely to attenuate neuropathic pain via inhibiting TNF-α synthesis and release in microglia. In addition to modulating TNF-α signaling, RvE1 may also inhibit neuropathic pain by down-regulating different proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2) and up-regulating the anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) (Serhan et al., 2008;Ji et al., 2011).

Our data also demonstrated that intrathecal post-treatment of RvE1 (10 ng), 3 weeks after nerve injury, could partially reverse SNL-induced mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia for 2 h (Fig. 1E,F). Thus, RvE1 may also be used to treat established neuropathic pain in the late phase, although RvE1 appears to be more effective in treating neuropathic pain in the early-phase.

In summary, RvE1 can reduce neuropathic pain via multiple mechanisms, by inhibiting (1) microglia signaling (e.g., TNF-α synthesis and release), (2) TRPV1 signaling, (3) downstream signaling of TNF-α, and (4) peripheral inflammation (neutrophil infiltration) (Ji et al., 2011). RvE1 may further promote the resolution of neuropathic pain via enhancing phagocytosis activity of macrophages and microglia (Serhan et al., 2008). Resolution of inflammation, glial activation, and neuropathic pain by endogenous proresolving mediators represent a conceptual change. Given the potent analgesic efficacy and safety profiles of endogenous lipid mediators, resolvins and their metabolically stable analogues such as 19-pf-RvE1 (Arita et al., 2006), as well as small molecule agonists targeting the resolvin’s signaling pathways, may offer new therapeutic tools for the management of destructive neuropathic pain. Noteworthy, it is equally important to prevent the development of chronic neuropathic pain after surgeries (e.g., amputation and thoracotomy) and treatment (chemotherapy) with pro-resolution-derived therapies.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants R01-DE17794, NS54932, and NS67686 to RRJ. TB was supported by a fellowship (PBLAP3-123417 and PA00P3-134165) from Switzerland. We thank the Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals Inc. for providing resolvins and Dr. Philip J. Vickers for helpful discussion

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no financial interest in this study.

References

- Arita M, Oh SF, Chonan T, Hong S, Elangovan S, Sun YP, Uddin J, Petasis NA, Serhan CN. Metabolic inactivation of resolvin E1 and stabilization of its anti-inflammatory actions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22847–22854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, De Koninck Y. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature. 2005;438:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia. 2002;40:140–155. doi: 10.1002/glia.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Suter MR. p38 MAPK, microglial signaling, and neuropathic pain. Mol Pain. 2007;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Xu ZZ, Strichartz G, Serhan CN. Emerging roles of resolvins in the resolution of inflammation and pain. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR. Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5189–5194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CK, Lu N, Xu ZZ, Liu T, Serhan CN, Ji RR. Resolving TRPV1- and TNF-α-mediated spinal cord synaptic plasticity and inflammatory pain with neuroprotectin D1. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15072–15085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2443-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Kress M. Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter MR, Wen YR, Decosterd I, Ji RR. Do glial cells control pain? Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;3:255–268. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanga FY, Nutile-McMenemy N, DeLeo JA. The CNS role of Toll-like receptor 4 in innate neuroimmunity and painful neuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501634102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Inoue K, Salter MW. Neuropathic pain and spinal microglia: a big problem from molecules in “small” glia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZZ, Zhang L, Liu T, Park JY, Berta T, Yang R, Serhan CN, Ji RR. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat Med. 2010;16:592–597. doi: 10.1038/nm.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Berta T, Xu ZZ, Liu T, Park JY, Ji RR. TNF-alpha contributes to spinal cord synaptic plasticity and inflammatory pain: distinct role of TNF receptor subtypes 1 and 2. Pain. 2011;152:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]