Abstract

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) accounts for a small fraction but aggressive form of epithelial breast cancer. Although the role of thrombin in cancer is beginning to be unfolded, its impact on the biology of IBC remains unknown. The purpose of this study was to establish the role of thrombin on the invasiveness of IBC cells. The IBC SUM149 cell line was treated with thrombin in the absence or presence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor Erlotinib and protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1)-inhibitor. The effects of pharmacological inhibitors on the ability of thrombin to stimulate the growth-rate and invasiveness were examined. We found that inhibiting putative cellular targets of thrombin action suppress both the growth and invasive of the SUM149 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, thrombin-mediated increased migration of SUM149 cells was routed through EGFR phosphorylation, and in-turn, stimulation of the p21-activated kinase (Pak1) activity in EGFR-sensitive manner. Interestingly, thrombin-mediated activation of the Pak1 pathway stimulation was blocked by Erlotinib and PAR1-inhibitor. For proof-of-principle studies, we found immunohistochemical evidence of Pak1 activation as well as expression of PAR1 in IBC. Thrombin utilizes EGFR to relay signals promoting SUM149 cell growth and invasion via Pak1 pathway. The study provides the rationale for future therapeutic approach in mitigating the invasiveness nature of IBC by targeting Pak1 and/or EGFR.

Keywords: Thrombin, EGFR, Pak1, Invasiveness, Inflammatory breast cancer

Introduction

Serine protease-thrombin is a pivotal element of the coagulation cascade converting fibrinogen into insoluble fibrins upon endothelial cell damage and thrombosis. Zymogen pro-thrombin is converted to an active thrombin by products of the coagulation cascade including Factor-Xa with the assistance of the cofactor Va. In addition to playing a role in blood coagulation, platelet adhesion and platelet aggregation, in recent years, thrombin has been associated with occult cancer because of its ability to promote the adhesion of tumor cell to platelets and endothelial cells, the main component of angiogenesis and thus, contributing to tumor growth and metastasis (1, 2). While it is known that thrombin generated during thrombosis including idiopathic venous thrombosis promotes malignancy in a variety of cancer, the role of thrombin on cancer cell biology remains poorly understood (2, 3).

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), the most lethal form of primary breast cancer, accounts for approximately 1 to 5% of all diagnosed breast cancer (4). The management of IBC has been improved in the past 4 decades; however, the therapeutic outcome remained a disappointment (5). The survival rate of 2.9 year for women with IBC is significantly shorter than that of non-T4-stage breast cancer (>10 years) (6). The stagnant improvement in therapeutic outcome can be attributed to the lack of understanding in the biology and the molecular mechanisms of IBC. Nevertheless, a closer examination of the IBC case studies will suggest that up to 30% of IBC patients have distant metastases as compared to a 5% in non-IBC patients (7), high-lighting the contribution of invasiveness in the noted mortality associated with IBC.

The metastatic nature of IBC, which does affect the survival rate, appears to utilize the components of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway (8,9). The overexpression of EGFR is associated with poor prognosis and reduced overall survival in cancer patients in general (9). The stimulation of EGFR promotes cell proliferation, tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis (8). In addition, stimulated EGFR activates MEK1 and 2, leading to cell migration and proliferation (8). Not only the morphologic switch and cellular motility have been shown to be regulated by EGFR but also by Pak1 (10–12). Furthermore, EGFR activation also leads to Pak1 stimulation via Nck1, an adopter protein which directly interacts with EGFR and Pak1 (13). Increased Pak1 expression and activity in human cancer, including breast cancer, is well documented (14–16). Higher tumor grade is associated with higher levels of Pak1 protein as well as activity (14). In addition to Pak1 overexpression, the kinase activity of Pak1 which is one of the targets of the activated Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 are also considered as markers of mammary gland tumor (16). Pak1 targets cytoskeletal organization by regulating the formation of motile structures modulated by small GTPases cdc42 and Rac1 (17). Pak1 also regulates cell metabolism, survival, differentiation, mitotic regulation, and anchorage-independent growth (18). It is believed that breast tumor cells use various mechanisms to upregulate Pak1-mediated signaling pathways to improve survival advantage, a needed phenotypic change for acquired metastatic potential.

Until now, although the roles of thrombin on the biology of breast cancer cells including MDA-MB-231 were investigated, there is no study on that of IBC cells. Therefore, in the present study, the effects of thrombin on the IBC cell biology were explored. We found that not only thrombin induces morphological change in SUM149 cell line but also promotes the invasiveness nature of these cells by activating EGFR and promoting Pak1 kinase activity. We found that inhibiting either downstream target of thrombin such as EGFR or hinder activity of the convergent point of all pathways can inhibit SUM149 cell growth and invasion. Our study provides a rationale for developing novel strategy to inhibit both the SUM149 cell growth and invasion, and attenuate the deleterious effects of thrombin derived from thromboembolism.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

The cell line SUM149 was obtained from Asterand (Detroit, MI). SUM149 cells were grown in Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech, Inc. Manassas, VA), 5 μg/mL insulin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)-F12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human thrombin was from Sigma. Erlotinib was obtained from LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA. SCH 79797 dihydrochloride was from Tocris Biosciences (Ellisville, MO). Anti-phosphotyrosine p-Tyr (PY99) and anti-EGFR antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). p-Pak1 and vinculin monoclonal antibodies were from Sigma. Anti-Pak1 antibody was from Bethyl Laboratories, Inc (Montgomery, TX). Anti-PAR1 antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Western blot (WB) analysis and immunoprecipitation (IP) were conducted as previously described (19). Briefly, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN], and phosphatase inhibitors). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes. The cell lysates were then resolved on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred (SDS-PAGE) to a nitrocellulose membrane, probed with the appropriate antibodies, and developed with the ECL reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For IP, lysates obtained from cells were subjected to IP with anti-phosphotyrosine p-Tyr antibody, followed by incubation with protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz). After washing, the eluates from the beads were subjected to WB.

Confocal microscopy

Cells were grown on glass cover slips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed with PBS three times, and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. Cells were incubated with phalloidin conjugated with 488-Alexa from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) for 30 min and washed with PBS three times. The DNA dye DAPI (Molecular Probes) was used as nuclear stain.

Cell viability assay

Cells were plated at a density of 4.0 × 103 cells/well (0.1 ml) in a 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were deprived of growth media for 12 hours prior of treatment. Cell viability was determined by XTT assay (Sigma) as per the instruction of the manufacturer. The percentage of cell viability of treated cells was determined by the ratio between absorbance of treated well and control well.

Invasion assay

BD biocoat matrigel invasion chamber 24-well plate 8.0 micron (BD Biosciences; 8 μm pore size) was used. Treated or non-treated cells (1 × 105 cells) were layered in the top chambers in the presence or absence of inhibitors for 12 hours. Non-migrated cells (top chamber) were removed post-incubation period. Migrated cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI for quantification. Images of random fields were captured by DP2-BSW software version 2.2 using Olympus Inverted microscope IX71 at 10× magnification (Uplan N 10X/0.30 Ph1 UIS2) (Center Valley, PA).

Pak1 kinase assay

Treated and control cell lysate (200 μg) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Pak1 antibody. Kinase assay was performed in kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM DTT) containing 20 μg myelin basic protein (MBP), 10 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP, and 20 μM cold ATP. The reaction was carried out in a volume of 30 μl for 30 min at 30°C and then stopped by the addition of 10 μl of 4×SDS buffer. We resolved the reaction products by SDS-PAGE and analyzed the results by autoradiography.

Immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinized sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by boiling the sections in 10 mM citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min. Sections were then incubated with anti-p-Pak1 antibody (1: 500 dilution) or anti-PAR1 antibody (1:100 dilution) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with EnVision (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature and visualization with liquid DAB+ substrate chromogen system (Dako). Immunostained sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with the use of the peramount mounting medium.

Results

Thrombin induces the growth, invasion, and cytoskeletal organization in SUM149 cells

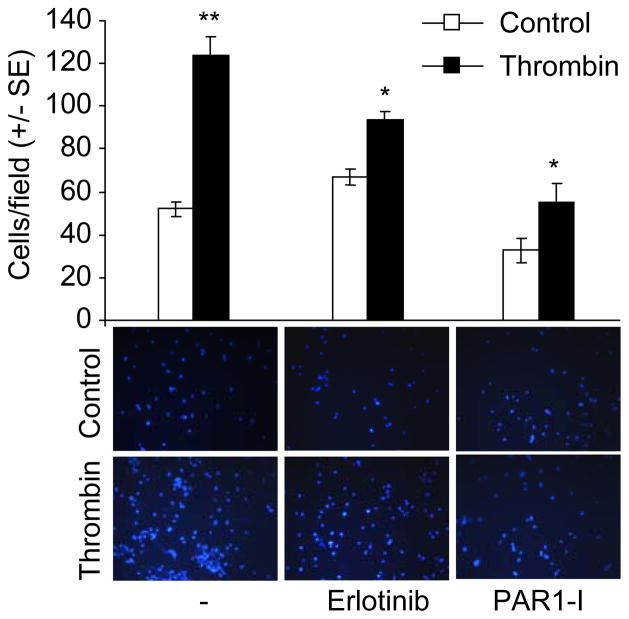

Previous studies have documented both inhibitory and inducible effects of thrombin on tumor cell growth, migration and invasion (1, 20). To understand the impact of thrombin on the biology of IBC cells, we first examined the effects of thrombin on IBC derived cell line SUM149 and non-IBC cell line MDA-MB-231 as a reference. We showed thrombin induces the growth of the SUM149 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, ranging from 0.125 to 0.5 U/mL (Fig. 1A). However, the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells was not changed by thrombin treatment. Interestingly, we found that the treatment with thrombin for 24 hours resulted in a distinct change in the morphology and cytoskeletal organization such as membrane ruffling in SUM149 cells, but not MDA-MB-231 cells, suggesting a dynamic effect of thrombin on the motility and invasiveness of the SUM149 cells (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Thrombin stimulation of SUM149 cell growth and membrane ruffling. (A) Effect of thrombin treatment (0–0.5 U/mL) on the SUM149 and MDA-MB-231 cell growth. (B) SUM149 and MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained for 24 hours in serum-free medium and then treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL) for 24 hours. The cells were fixed and immunofluorescent labeled with fluorescently conjugated phalloidin (for F-actin) and DAPI (for DNA). Arrows show the membrane ruffling induced by thrombin treatment. The number of SUM149 cells with the membrane ruffling were counted after taking pictures by confocal microscopy and represented as percentage of total cell number in the pictures. *P = 2.09 × 10−10. Scale bar = 10μm.

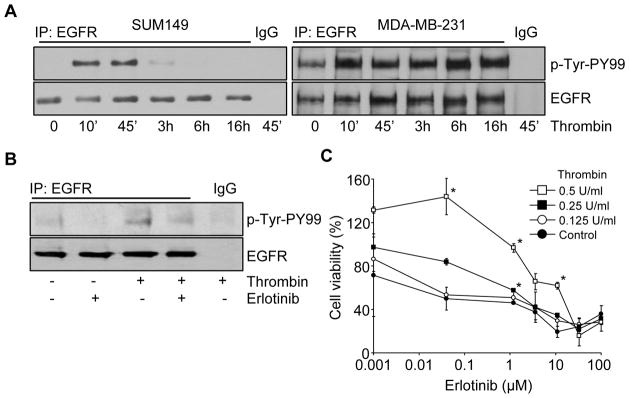

Thrombin induces EGFR phosphorylation in SUM149 cells

Since thrombin was reported to activate EGFR via protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) in breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells (21), we next investigated whether thrombin could also activate EGFR in SUM149 and MDA-MB-231 cells. In Figure 2A, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with p-Tyr-PY99 antibody, followed by probing with anti-EGFR antibody. The results showed that thrombin efficiently induced the activation of EGFR within 10 min in SUM149 cells as well as the quick activation of EGFR in MDA-MD-231 cells as expected from previous study (21). The thrombin-induced EGFR phosphorylation was effectively compromised by the treatment of the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor Erlotinib in SUM149 cells (Fig. 2B). Previous study has shown that the blockage of EGFR activation by Erlotinib inhibits effectively the proliferation, migration, invasion and anchorage-independent growth of the IBC SUM149 cells (8). Therefore, we decided to use Erlotinib to determine whether it could inhibit the thrombin-induced proliferation in SUM149 cells. Like-wise, we found that the inclusion of Erlotinib also inhibits thrombin-induced SUM149 cell growth in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 2C). Increasing thrombin concentrations from 0.125 U/mL to 0.5 U/mL shifted the IC50 of Erlotinib in SUM149 from 1.4 to 15 μM, respectively, suggesting the effect of thrombin in the biology of the cells may be mediated via the EGFR pathway.

Figure 2.

Thrombin-induced phosphorylation of EGFR in SUM149 cells. (A) Serum-starved SUM149 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with or without thrombin (0.5 U/mL) for various times before preparing the cell lysates. After immunoprecipitation of the cell lysates with anti-EGFR antibody or IgG, EGFR phosphorylation was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-p-Tyr-PY99 antibody. The level of total EGFR was checked by immunoblotting using anti-EGFR antibody. (B) Serum-starved SUM149 cells were treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL) and with or without Erlotinib pretreatment (50 μM), and EGFR phosphorylation was analyzed as above. (C) Cell viabilities were measured after treatment with thrombin (0–0.5 U/mL) and Erlotinib (0–100 μM). Data represent the mean ± SE. *P < 0.001.

Thrombin stimulates Pak1 activity in SUM149 cells

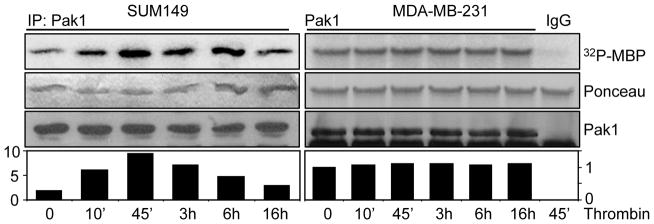

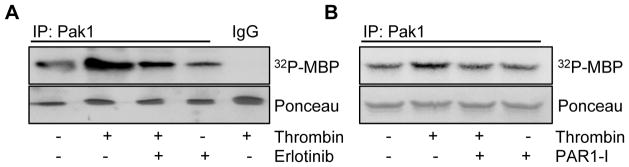

Previous studies have demonstrated that EGFR activation is crucial for the motility and invasiveness of cancer cells by stimulating Pak1 activity (19, 22). Since IBC patients are often at risk of metastasis, we hypothesized that thrombin might modulate the biology of IBC cells by activating EGFR and Pak1 pathways. As illustrated in SUM149 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, we found that thrombin induced the Pak1 activation in the first 6 hours of treatment in SUM149 cells but not MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3). Interestingly, Pak1 protein expression levels were not altered during these periods of thrombin treatments. To independently validate the finding that thrombin promotes Pak1 activity via EGFR pathway, thrombin-stimulated SUM149 cells were exposed to Erlotinib before assaying the Pak1 activity. As shown in Figure 4A, Erlotinib inclusion substantially blocked the Pak1 kinase stimulation by thrombin in SUM149 cells. Since thrombin signaling is mediated by protease-activated receptors family, a small family of G protein-coupled namely PARs. Therefore, we further assessed whether thrombin-induced Pak1 activation could be blocked or reduced by pre-treating the cells with the PAR1-inhibitor SCH 79797. We found that indeed, inclusion of the PAR1-inhibitor suppressed the Pak1 kinase activity (Figure 4B), confirming the ability of thrombin to induce Pak1 kinase activity in IBC cells.

Figure 3.

Thrombin stimulates Pak1 activity in SUM149 cells. Cell lysates were made from SUM149 and MDA-MB-231 cells treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL) for various times. After immunoprecipitation of the cell lysates with anti-Pak1 antibody or IgG, Pak1 kinase activity was analyzed by kinase assay using MBP as a substrate. The middle panels are Ponceau S-stained blots showing MBP. The lower panels are the total Pak1 level determined by immunoblotting using anti-Pak1 antibody.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of thrombin-induced Pak1 activity by EGFR and PAR1 inhibitors in SUM149 cells. (A) Serum started SUM149 cells were treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL) and with or without Erlotinib pretreatment (50 μM). After immunoprecipitation of the cell lysates with anti-Pak1 antibody or IgG, Pak1 kinase activity was analyzed by kinase assay using MBP as a substrate. The lower panels are Ponceau S-stained blots showing MBP. (B) Serum starved SUM149 cells were treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL) and with or without PAR1-I pretreatment (500 nM), followed by cell lysis to measure the Pak1 kinase activity as above. The lower panel is Ponceau S-stained blot showing MBP.

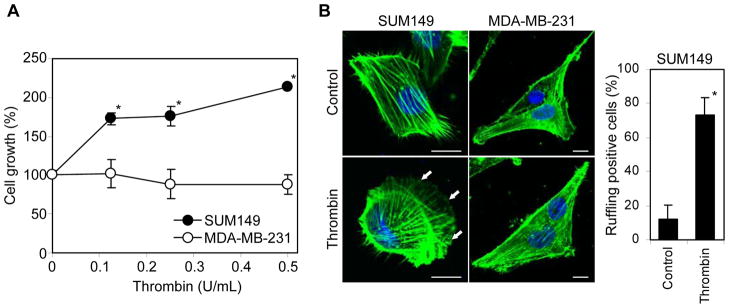

Thrombin induces SUM149 cell’s invasiveness

Since thrombin treatment of SUM149 cells was accompanied by a dramatic cytoskeleton remodeling, we investigated the effect of thrombin on the invasiveness of SUM149 cells. Thrombin, at a concentration of 0.5 U/mL, enhanced the ability of SUM149 cells to invade to the lower chamber of matrigel coated transwell (Fig. 5). The inclusion of PAR1-inhibitor, SCH 79797 also reduced the number of invading SUM149 cells, confirming the intimate role of thrombin to the invasiveness characteristic of the IBC cells. Because of an essential role of EGFR in cancer cell proliferation, tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis, we hypothesized that thrombin may render its effect via the EGFR-Pak1 pathway. Using a concentration of Erlotinib that does not reduce cell viability, we were able to suppress thrombin-induced SUM149 cell invasion by Erlotinib. Altogether, these results establish that thrombin influences the invasive nature of the IBC cells via the EGFR-Pak1 pathway.

Figure 5.

Thrombin-induced invasiveness of the SUM149 cells. SUM149 cells (1 × 105 cells) treated with or without thrombin (0.5 U/mL), Erlotinib (50 μM), or PAR1-I (200 nM) were added on upper side of matrigel invasion chamber and incubated overnight. Subsequently, the invaded cells were fixed, stained with DAPI and counted under microscope. Data represent the mean ± SE. *P < 0.01. **P < 0.001.

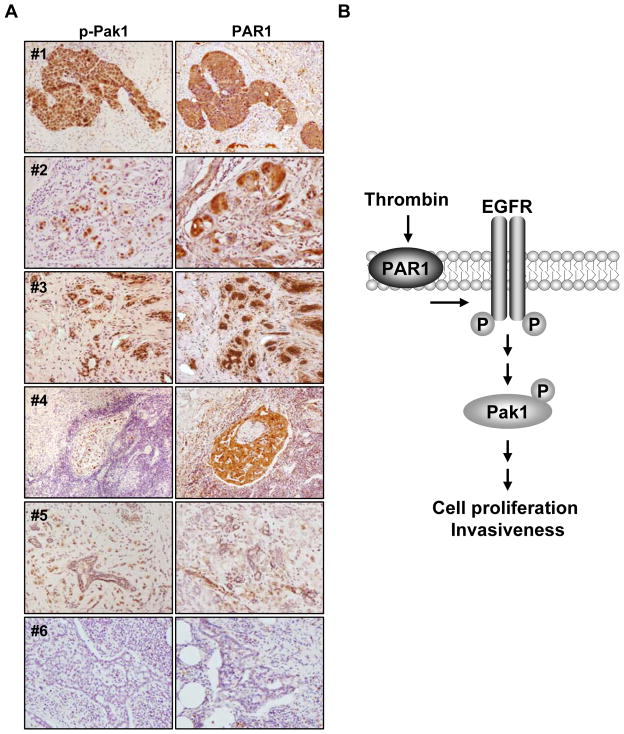

Expression of p-Pak1 and PAR1 in IBC tissues

Although Pak1 expression levels are not altered upon thrombin treatment, high levels of activated phosphorylated Pak1 is readily induced by thrombin in the SUM149 cell line. To validate the relationship of p-Pak1 and PAR1 in IBC, we carried out a proof-of-principle study and examined a total of thirteen tissues (breast: 7, skin: 3, lymph node: 3) from IBC patients using anti-p-Pak1 and anti-PAR1 antibodies (Fig. 6A). The immunostaining intensity matched very well between p-Pak1 and PAR1 in all IBC tissue samples. Ten of thirteen tissues displayed strong nuclear immunostaining of p-Pak1 and PAR1 (the representative five samples, #1–#5 were shown.), and the moderate, weak and negative (#6) reactivities were seen in each one case. In non-neoplastic breast ducts and stroma, p-Pak1 staining was weakly positive or negative. PAR1 staining was strong to weak dependent on the specimens. Since EGFR is known to be activated in IBC (8), these results suggest that in-principle, IBC may contain stimulated Pak1 pathway.

Figure 6.

Status of activated p-Pak1 and PAR1 in IBC tissues (A) The expression level of p-Pak1 and PAR1 were assayed in tumor tissue samples from IBC patients using anti-p-Pak1 and anti-PAR1 antibodies. Histological characteristics of tumors #1 and #4, lymph node; #2, #3 and #5, breast tissues; #6, negative staining in lymph node. (B) Proposed working model for the activation of thrombin-induced signaling pathway via EGFR and Pak1 activation. Thrombin induces EGFR phosphorylation, and subsequently, Pak1 activation, leading to the activation of oncogenic signaling including cell proliferation and invasiveness in inflammatory breast cancer.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence suggest a role of thrombin in extravasculature tissues and in cancer. Many of previous studies have revealed inducible effects of thrombin on growth, migration and invasion of cancer cells including breast (1), lung (23), gastric (24), colon (25), prostate (26), and brain (27), although a few studies reported inhibitory effect of thrombin on those (2, 28). Here, we report for the first time that thrombin induces the proliferation and invasiveness in IBC cells trough EGFR and Pak1 activation by PAR1.

Thrombin is known to transactivate EGFR in several cancer cells (21, 25, 29). Thrombin promotes cell proliferation of colon cancer through EGFR transactivation and Src activation and subsequently, leads to PAR1-mediated ERK1/2 activation (25). Renal carcinoma cell migration is promoted by thrombin through PAR1-mediated EGFR transactivation (29). In breast cancer, proteolytic activation of PAR1 by thrombin promotes cell invasion by stimulating the induction of persistent transactivation of EGFR and ErbB2/HER2 and subsequently, a prolonged ERK1/2 signaling (21). Since Pak1 is a component of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway (30), which have been associated with cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness, the Pak1 activation by thrombin could also mediates SUM149 cell proliferation and invasion via ERK1/2 activation as shown here. Pak1 has been shown to be involved in the regulation of tissue factor expression in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by thrombin through the signaling activation of the kinase including ERK1/2 (31).

Pak1 also regulates dynamic cytoskeletal changes required for a productive cell motility and invasion by cancer cells (10). Since thrombin treatment induces prominent cytoskeletal remodeling including membrane ruffling in SUM149 cells, we have now found that Pak1 activation by thrombin might play a role in the regulation of membrane ruffling. Pak1 regulates actin reorganization through the phosphorylation of substrates including LIM kinase (32). Further, since LIM kinase 1 activity is required for thrombin-induced microtubule destabilization and actin polymerization (17), the activation of LIM kinase by thrombin-activated Pak1 might be involved in the cytoskeletal organization in the SUM149 cells.

Since previous study also showed that EGFR expression was positive in 30% of patients with IBC and associated with increased risk of IBC recurrence (33, 9) and in cancer in general (34, 35), EGFR is believed to be a potential therapeutic target in IBC (8). Drugs targeting EGFR have been developed for approximately 30 years. EGFR-targeting drugs including anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been approved and in advanced development for the treatment of cancer including non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and pancreatic cancer (36). However, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor was reported to not have significant clinical activity in breast cancer patients (37, 38) and there were no correlation between the sensitivities to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and the levels of EGFR expression in the breast cancer cell lines (39, 40). Also, toxicities including skin toxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, cardial toxicity and allergic reactions are known to associate with anti-EGFR drug treatment (41). Further, in addition to the primary resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor due to mutation in EGFR gene or KRAS gene, acquired resistance due to a single secondary mutation T790M in EGFR exon 20 limits EGFR-targeted therapy in the case of non-small cell lung cancer (42). Moreover, several molecular-designed studies have identified potential targets in the diagnosis and therapy of IBC (4, 43, 44) which are currently under development. In addition to these studies, the facts that thrombin transactivate EGFR in cancer cells made us selectively aim to influence cellular malignant characteristics of IBC by inhibiting PAR1 and EGFR to impair the invasiveness of the IBC cells. For the first time, we have shown the involvement of Pak1 in cancer biological function including proliferation and invasiveness of SUM149 cells via thrombin-mediated EGFR activation (Fig. 6B). Our present study suggests that in addition to the drugs which specifically inhibit PAR1 and EGFR, Pak1-targeted drugs might prove to be effective in IBC, either as a single agent or in combination of with targeted therapeutics to evolve an effective anti-IBC therapeutic strategy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA98823 (RK).

References

- 1.Even-Ram S, Uziely B, Cohen P, Grisaru-Granovsky S, Maoz M, Ginzburg Y, et al. Thrombin receptor overexpression in malignant and physiological invasion processes. Nat Med. 1998;4:909–14. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nierodzik ML, Karpatkin S. Thrombin induces tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis: Evidence for a thrombin-regulated dormant tumor phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snyder KM, Kessler CM. The pivotal role of thrombin in cancer biology and tumorigenesis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34:734–41. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1145255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Merajver SD. Molecular biology of breast cancer metastasis. Inflammatory breast cancer: clinical syndrome and molecular determinants. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:423–9. doi: 10.1186/bcr89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sportès C, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ, Gea-Banacloche J, Danforth DN, Avila DN, et al. Strategies to improve long-term outcome in stage IIIB inflammatory breast cancer: multimodality treatment including dose-intensive induction and high-dose chemotherapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:963–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine PH. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:966–75. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine PH, Steinhorn SC, Ries LG, Aron JL. Inflammatory breast cancer: the experience of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;74:291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D, LaFortune TA, Krishnamurthy S, Esteva FJ, Cristofanilli M, Liu P, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor reverses mesenchymal to epithelial phenotype and inhibits metastasis in inflammatory breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6639–48. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabioglu N, Gong Y, Islam R, Broglio KR, Sneige N, Sahin A, et al. Expression of growth factor and chemokine receptors: new insights in the biology of inflammatory breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1021–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sells MA, Knaus UG, Bagrodia S, Ambrose DM, Bokoch GM, Chernoff J. Human p21-activated kinase (Pak1) regulates actin organization in mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 1997;7:202–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(97)70091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adam L, Vadlamudi R, Kondapaka SB, Chernoff J, Mendelsohn J, Kumar R. Heregulin regulates cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration through the p21-activated kinase-1 via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28238–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sells MA, Boyd JT, Chernoff J. p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1) regulates cell motility in mammalian fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:837–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar R, Gururaj AE, Barnes CJ. p21-activated kinases in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:459–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vadlamudi RK, Adam L, Wang RA, Mandal M, Nguyen D, Sahin A, et al. Regulatable expression of p21-activated kinase-1 promotes anchorage-independent growth and abnormal organization of mitotic spindles in human epithelial breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36238–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balasenthil S, Sahin AA, Barnes CJ, Wang RA, Pestell RG, Vadlamudi RK, et al. p21-activated kinase-1 signaling mediates cyclin D1 expression in mammary epithelial and cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1422–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang RA, Zhang H, Balasenthil S, Medina D, Kumar R. PAK1 hyperactivation is sufficient for mammary gland tumor formation. Oncogene. 2006;25:2931–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:253–9. doi: 10.1038/12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dummler B, Ohshiro K, Kumar R, Field J. Pak protein kinases and their role in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:51–63. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Wang RA, Adam L, Papadimitrakopoulou VV, Clayman GL, et al. The epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 (Iressa) suppresses c-Src and Pak1 pathways and invasiveness of human cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:658–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0382-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamath L, Meydani A, Foss F, Kuliopulos A. Signaling from protease-activated receptor-1 inhibits migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5933–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arora P, Cuevas BD, Russo A, Johnson GL, Trejo J. Persistent transactivation of EGFR and ErbB2/HER2 by protease-activated receptor-1 promotes breast carcinoma cell invasion. Oncogene. 2008;27:4434–45. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes CJ, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Mandal M, Yang Z, Clayman GL, Hong WK, et al. Suppression of epidermal growth factor receptor, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and Pak1 pathways and invasiveness of human cutaneous squamous cancer cells by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 (Iressa) Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:345–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin E, Fujiwara M, Pan X, Ghazizadeh M, Arai S, Ohaki Y, et al. Protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1 and PAR-2 participate in the cell growth of alveolar capillary endothelium in primary lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer. 2003;97:703–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimoto D, Hirono Y, Goi T, Katayama K, Matsukawa S, Yamaguchi A. The activation of Proteinase-Activated Receptor-1 (PAR1) mediates gastric cancer cell proliferation and invasion. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:443–57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darmoul D, Gratio V, Devaud H, Peiretti F, Laburthe M. Activation of proteinase-activated receptor 1 promotes human colon cancer cell proliferation through epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:514–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu L, Ibrahim S, Liu C, Skaar J, Pagano M, Karpatkin S. Thrombin induces tumor cell cycle activation and spontaneous growth by down-regulation of p27Kip1, in association with the up-regulation of Skp2 and MiR-222. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3374–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua Y, Tang L, Keep RF, Schallert T, Fewel ME, Muraszko KM, et al. The role of thrombin in gliomas. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1917–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang YQ, Li JJ, Karpatkin S. Thrombin inhibits tumor cell growth in association with up-regulation of p21(waf/cip1) and caspases via a p53-independent, STAT-1-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6462–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergmann S, Junker K, Henklein P, Hollenberg MD, Settmacher U, Kaufmann R. PAR-type thrombin receptors in renal carcinoma cells: PAR1-mediated EGFR activation promotes cell migration. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:889–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang Y, Chen Z, Ambrose D, Liu J, Gibbs JB, Chernoff J, et al. Kinase-deficient Pak1 mutants inhibit Ras transformation of Rat-1 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4454–64. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Görlach A, BelAiba RS, Hess J, Kietzmann T. Thrombin activates the p21-activated kinase in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Role in tissue factor expression. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:1168–75. doi: 10.1160/TH05-01-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorovoy M, Niu J, Bernard O, Profirovic J, Minshall R, Neamu R, et al. LIM kinase 1 coordinates microtubule stability and actin polymerization in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26533–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502921200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guérin M, Gabillot M, Mathieu MC, Travagli JP, Spielmann M, Andrieu N, et al. Structure and expression of c-erbB-2 and EGF receptor genes in inflammatory and non-inflammatory breast cancer: prognostic significance. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:201–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sporn MB, Todaro GJ. Autocrine secretion and malignant transformation of cells. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:878–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010093031511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1995;19:183–232. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00144-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Minckwitz G, Jonat W, Fasching P, du Bois A, Kleeberg U, Lück HJ, et al. A multicentre phase II study on gefitinib in taxane- and anthracycline-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:165–72. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1720-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baselga J, Albanell J, Ruiz A, Lluch A, Gascón P, Guillém V, et al. Phase II and tumor pharmacodynamic study of gefitinib in patients with advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5323–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campiglio M, Locatelli A, Olgiati C, Normanno N, Somenzi G, Viganò L, et al. Inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in breast cancer cells by the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 (‘Iressa’) is independent of EGFR expression level. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198:259–68. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamasaki F, Zhang D, Bartholomeusz C, Sudo T, Hortobagyi GN, Kurisu K, et al. Sensitivity of breast cancer cells to erlotinib depends on cyclin-dependent kinase 2 activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2168–77. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harandi A, Zaidi AS, Stocker AM, Laber DA. Clinical Efficacy and Toxicity of Anti-EGFR Therapy in Common Cancers. J Oncol. 2009;2009:567486–567500. doi: 10.1155/2009/567486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–81. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parton M, Dowsett M, Ashley S, Hills M, Lowe F, Smith IE. High incidence of HER-2 positivity in inflammatory breast cancer. Breast. 2004;13:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cristofanilli M. Novel targeted therapies in inflammatory breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:2837–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]