Abstract

In endemic areas, Plasmodium vivax relapses are difficult to distinguish from new infections. Genotyping of patients who experience relapse after returning to a malaria-free area can be used to explore the nature of hypnozoite activation and relapse. This paper describes a person who developed P. vivax malaria for the first time after travelling to Boriziny in the malaria endemic coastal area of Madagascar, then suffered two P. vivax relapses 11 weeks and 21 weeks later despite remaining in Antananarivo in the malaria-free central highlands area. He was treated with the combination artesunate + amodiaquine according to the national malaria policy in Madagascar. Genotyping by PCR-RFLP at pvmsp-3α as well as pvmsp1 heteroduplex tracking assay (HTA) showed the same dominant genotype at each relapse. Multiple recurring minority variants were also detected at each relapse, highlighting the propensity for multiple hypnozoite clones to activate simultaneously to cause relapse.

Background

In Madagascar, the combination of artesunate + amodiaquine (ASAQ) is recommended since December 2005 as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated and non-severe malaria, regardless of the parasite species involved. One of the important differences between Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax is the formation of hypnozoites that can cause relapses after a course of treatment [1]. Such relapses have been described as clonal in origin in individuals returning to non endemic areas [2], but more recent evidence suggests that multiple low-frequency variants commonly arise during relapse [3,4]. In this report is described a case where sequential P. vivax malaria relapses in a patient living in Antananarivo, a malaria-free urban area, following ASAQ treatment comprised multiple minority-variant parasites, suggesting simultaneous reactivation of multiple hypnozoite clones.

Case description

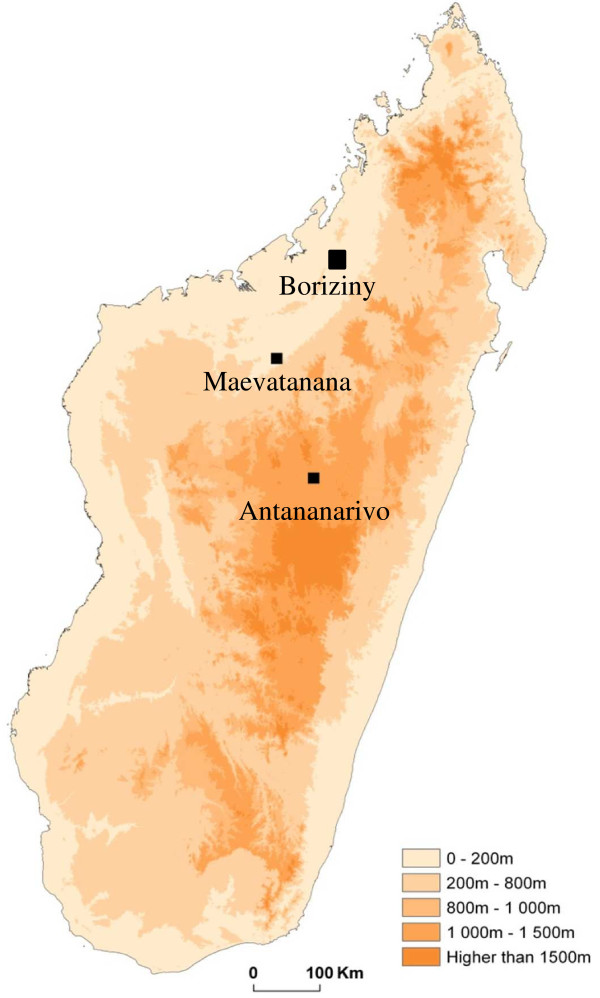

From May to November 2010, a 23 year old Malagasy man residing in Antananarivo travelled regularly to Boriziny (north-western Madagascar) as a ground transporter. He spent one to six nights there every one to two weeks without taking precautions to prevent mosquito bites. Antananarivo is the capital of Madagascar, situated in the central highlands at 1,200 m above sea level, and there is no malaria transmission throughout the city [5]. Boriziny (previously named Port Berger) is in a zone of tropical malaria transmission in north-western Madagascar, situated at less than 40 m above sea level (Figure 1). The subject returned from Boriziny on November 19, 2010 and reported having fever and chills on the evening of November 22, 2010. These symptoms were accompanied by sweating and fatigue. On the morning of November 23 (D0), he came to the malaria unit at the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar (IPM). Thick and thin peripheral blood smear were prepared, stained with Giemsa and microscopically examined as previously described [6]. Microscopy revealed P. vivax monoinfection with a parasitaemia of 6,687 parasites/μl. According to the malaria treatment policy in Madagascar, the patient was treated with a combination of artesunate + amodiaquine over three days (ASAQ Winthrop® for adults, artesunate 100 mg + amodiaquine 270 mg per tablet and 2 tablets per day). The first dose of ASAQ for D0 was administered under direct medical observation, with monitoring to insure that the patient did not vomit. He was given the ASAQ doses for D1 and D2 and was advised to return to the laboratory if malaria symptoms recurred. The subject spoke to staff from IPM on D1, D2 and D7 and reported that all symptoms were completely resolved. Prior to drug administration, as part of the national network for drug resistance surveillance established in Madagascar since 1999 (authorization no. 517-SAN/SG/DLMT/SLP and ethical clearance no. 013/04/SANPF/CAB), blood samples were collected on filter paper and kept at −20°C until use.

Figure 1.

Map of Madagascar showing the geographical location of Boriziny and Antananarivo.

Following the first malaria episode on November 23, 2010, the patient remained in Antananarivo and did not travel back to Boriziny. However, on February 9, 2011 (D78), he developed fever and chills again and returned to the malaria unit at IPM. Plasmodium vivax monoinfection was confirmed by microscopy with a parasitaemia of 3,208 parasites/μl. Blood sample was collected on filter paper. The patient was again treated with ASAQ as described. The medical staff at IPM wanted to add primaquine to the treatment but none was available in Madagascar. After one week, the patient reported that symptoms had completely resolved.

Again, the patient remained in Antananarivo, but on April 22, 2011 (D150 with reference to the first attack in November 2010), he experienced similar symptoms as previously reported and returned to the the malaria unit at IPM. Microscopy was performed and P. vivax monoinfection was confirmed again with a parasitaemia of 63 parasites/μl. A blood sample was collected on filter paper, and the patient was treated with ASAQ for a third time. After a week, the patient reported that symptoms had completely resolved. Since November 2011, the subject has been living in France and has reported no further symptoms. Last contact was made with the subject on January 16, 2013.

Plasmodium vivax genotyping

Parasite DNA extracted from filter paper blood samples was analysed to compare the genotypic profile of the P. vivax isolates collected from the patient during each of the three malaria episodes. Using an Instagen kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories Headquarters, France), DNA was extracted from the blood spots. Nested-PCR was used to confirm P. vivax monoinfection in the three samples from D0, D78 and D150 [7]. DNA from P. vivax collected from Maevatanana – a study site distant from Boriziny, was used as positive control. Human DNA from a blood donor from the HJRA University Hospital in Antananarivo was used as negative control. The lack of DNA contamination was checked using a blank (without DNA) in each run.

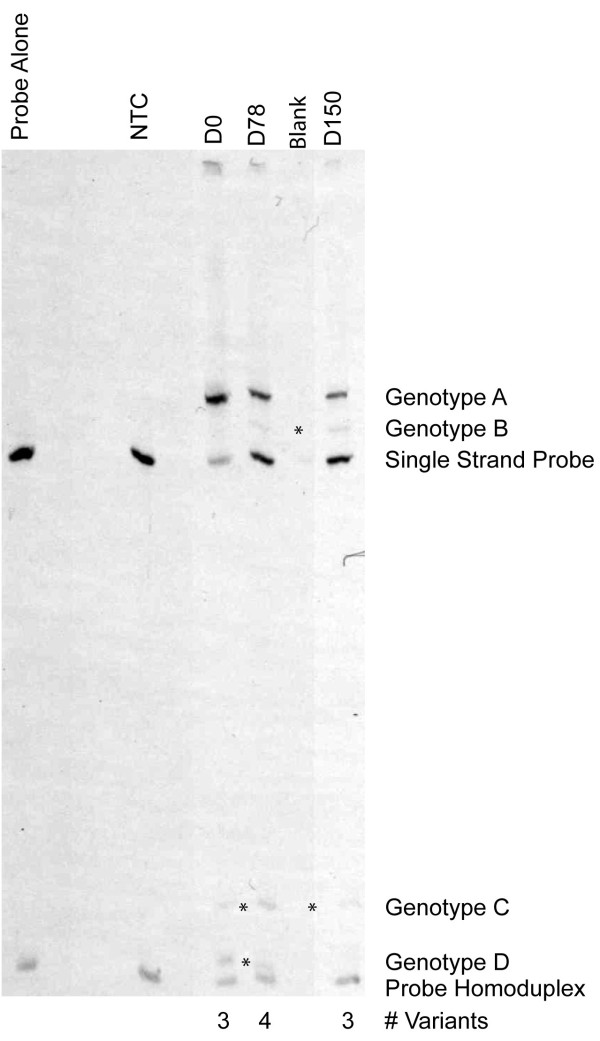

Next, P. vivax isolates were typed at pvmsp-3α as described elsewhere [8] to compare the D0, D78 and D150 genotypes. Using PCR-RFLP with AluI and HhaI restriction enzymes for pvmsp-3α, it was shown that the dominant strain of P. vivax causing the malaria attacks at D0, D78 and D150 was the same (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-3α (pvmsp-3α) restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns after digestion with the restriction enzymes Alu I (2A) and Hha I (2B). Lanes PC positive control, NTC negative control, Blank without DNA and D0, D78, D150 P. vivax samples from the patient. DNA size markers are shown in lanes labelled MW with sizes shown in basepairs (bp). MW: molecular weight (base pairs); PC: positive control; NTC: negative control; Blank: without DNA.

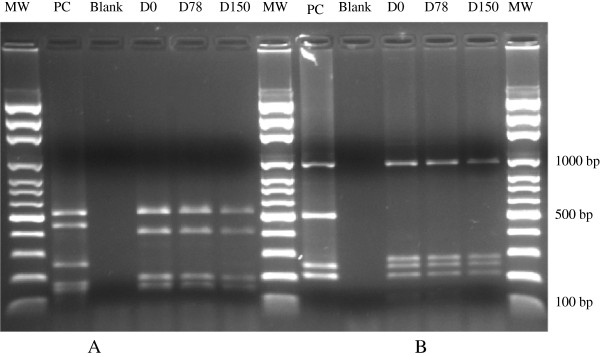

Plasmodium vivax infections are often polyclonal in nature, harbouring more than one genetic strain or variant at once [9,10]. The number of genetic variants found simultaneously within a host is referred to as the multiplicity of infection. To get a more nuanced understanding of the multiplicity of infection within the initial and relapsing isolates, a heteroduplex tracking assay (HTA) targeting the highly variable P. vivax merozoite surface protein 1 gene (pvmsp-1) as previously described was used [3]. It was demonstrated that the initial as well as two subsequent malaria episodes each harboured multiple pvsmp1 variants by HTA, labelled Genotype A-D in Figure 3, yielding multiplicity of infections (MOIs) of 3–4. With each episode, genotype A remained the dominant genotype, as implied by the darkness of the band, while 2–3 other genotypes were detected as minority variants. On D0, genotype C represents a minority variant that recurred both 11 and 21 weeks later on D78 and D150. Genotype D, also found at D0, recurred at D78, but was not detected at D150. Finally, genotype B was not appreciated in the initial isolate, but appeared at D78 and recurred at D150 (Figure 3). Taken together, this pattern of multiple relapsing variants suggests that polyclonal P. vivax infections reactivate hypnozoites in a multiclonal fashion. While genotype B appeared as a novel variant at D78, possibly suggesting a new infection from a mosquito inoculation, the clinical history of the patient combined with the recurrence of genotype B at D150 strongly suggest that genotype B was present, but not appreciated in the initial D0 infection and achieved greater patency in the relapsing infections. Because it is not certain that this is the subject’s first bout of malaria, another possibility is that genotype B represents a reactivated latent hypnozoite from a prior P. vivax infection, preceding November 2010.

Figure 3.

Plasmodium vivax msp1 heteroduplex tracking assay of the parasite isolates derived from the patient. Each lane contains bands representing the sing-stranded HTA probe and probe homoduplex (seen in the NTC and probe alone lanes). The day of follow-up is indicated at the top of each lane. Unique pvmsp1 genotypes A-D were identified as bands that migrated differently from the single-stranded probe or probe homoduplex bands and are marked as asterisks. These represent heteroduplexes formed between the probe and amplified PCR product from each patient sample. Asterisks are placed between shared minority variants.

Concluding remarks

The case reported herein involves P. vivax malaria imported from the coastal area to the central highland area in Madagascar. Repetitive ASAQ treatment administered according to the national malaria treatment policy was effective in treating the acute illness in the patient but relapses occurred twice. Parasitaemia was lower at each subsequent attack. Pvmsp-3α genotyping indicated that the same major strain was present during the three consecutive attacks. However, such PCR-based genotyping can miss other genotypes also present in low numbers. The HTA analysis suggests that multiple other clones were involved in the relapse.

Plasmodium vivax malaria is characterized by relapses after resolution of the primary infection, derived from activation of dormant hypnozoites in the liver [11]. The efficacy of ASAQ has been proven for treating uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria [6] and P. vivax malaria (Randrianarivelojosia, personal communication) in Madagascar. Regarding the case reported in this paper, P. vivax malaria occurring more than 70 days post-treatment in a patient living in the central highland does not indicate recrudescence due to ASAQ treatment failure; rather, it is indicative of typical relapse. Plasmodium vivax is the second most prevalent species of human malaria parasite behind P. falciparum in Madagascar, but it occurs in less than 5 %; of biologically confirmed malaria cases [12,13]. Thus, it is logical to give ACT universally for all Plasmodium species whether P. falciparum or P. vivax. However, P. vivax-specific treatment of hypnozoites in the form of primaquine for radical cure is not the policy in Madagascar. A subset of patients will suffer relapse as in this gentleman. From a public health perspective, it would be important eventually to take into account the use of primaquine to eradicate dormant P. vivax hypnozites and prevent these relapses.

To some degree, the level of genetic complexity seen in malaria infections is associated with transmission intensity. Even though P. falciparum dominates malaria transmission in Madagascar, the detection of multiple minority-variants of P. vivax in the reported case suggests that genetic diversity of P. vivax parasites exists to the extent that polyclonal P. vivax infections are not rare. None of the minority variants detected evolved into the predominant strain at relapse. However, the detection of these minority variants allowed a more nuanced appreciation of the mechanisms of hypnozoite activation within a polyclonal infection. Simultaneous hypnozoite activation and relapse of multiple clones promotes genetic diversity in the parasite population as whole, and such relapse may be an important mechanism for maintaining high P. vivax genetic diversity even in areas of relatively low transmission. Furthermore, the ability to detect multiple recurring strains of the same type can lend further evidence that a recurrent malaria episode indeed represents relapse rather than new infection.

Consent

In line with any activities part of the national network for malaria drug resistance surveillance (ethical clearance no. 013/04-SANPF/CAB on January, 21, 2004), written informed consent was obtained from the patient for blood and information collection, for follow up, and for publication of this report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to preparing the final version of the manuscript. VA, JL, JJ and MR were in charge of the parasite genotyping and the microscopy. MR and JJ are guarantors of the paper.

Contributor Information

Voahangy Andrianaranjaka, Email: vandrianaranjaka@pasteur.mg.

Jessica T Lin, Email: jessica_lin@med.unc.edu.

Christopher Golden, Email: cgolden@fas.harvard.edu.

Jonathan J Juliano, Email: jonathan_juliano@med.unc.edu.

Milijaona Randrianarivelojosia, Email: milijaon@pasteur.mg.

Acknowledgements

The laboratory works were financially supported by the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar mainly through the Project NSA Project MDG-910-G19-M; and by the University of North Carolina, USA from the National Institutes of Health [grant number AI089819 to JJJ]. JTL was supported by a National Institutes of Health Infectious Disease Pathogenesis Research Training Grant [grant number 5T32AI0715132] and the North Carolina Clinical and Translational Science Award [grant number UL1RR025747]. We are grateful to Elisabeth Ravaoarisoa, Seheno Razanatsiorimalala and Rogelin Raherinjafy for their technical support.

References

- Chamchod F, Beier JC. Modeling Plasmodium vivax: Relapses, treatment, seasonality, and G6PD deficiency. J Theor Biol. 2012;316C:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Auliff A, Rieckmann K, Gatton M, Cheng Q. Relapses of Plasmodium vivax infection result from clonal hypnozoites activated at predetermined intervals. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:934–941. doi: 10.1086/512242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Patel J, Kharabora O, Sattabongkot J, Muth S, Ubalee R, Schuster A, Rogers W, Wongsrichanalai C, Juliano J. Plasmodium vivax isolates from Cambodia and Thailand show high genetic complexity and distinct patterns of P. vivax multidrug resistance gene 1 (pvmdr1) polymorphisms. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- de Araujo FC, de Rezende AM, Fontes CJ, Carvalho LH, Alves de Brito CF. Multiple-clone activation of hypnozoites is the leading cause of relapse in Plasmodium vivax infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabarijaona LP, Ariey F, Matra R, Cot S, Raharimalala AL, Ranaivo LH, Le Bras J, Robert V, Randrianarivelojosia M. Low autochtonous urban malaria in Antananarivo (Madagascar) Malar J. 2006;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye JL, Randrianarivelojosia M, Sagara I, Brasseur P, Ndiaye I, Faye B, Randrianasolo L, Ratsimbasoa A, Forlemu D, Moor VA, Traore A, Dicko Y, Dara N, Lameyre V, Diallo M, Djimde A, Same-Ekobo A, Gaye O. Randomized, multicentre assessment of the efficacy and safety of ASAQ–a fixed-dose artesunate-amodiaquine combination therapy in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2009;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MC, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Snounou G, Day KP. Polymorphism at the merozoite surface protein-3alpha locus of Plasmodium vivax: global and local diversity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:518–525. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepfli C, Ross A, Kiniboro B, Smith TA, Zimmerman PA, Siba P, Mueller I, Felger I. Multiplicity and diversity of Plasmodium vivax infections in a highly endemic region in Papua New Guinea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JT, Juliano JJ, Kharabora O, Sem R, Lin FC, Muth S, Menard D, Wongsrichanalai C, Rogers WO, Meshnick SR. Individual Plasmodium vivax msp1 variants within polyclonal P. vivax infections display different propensities for relapse. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1449–1451. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06212-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NJ, Imwong M. Relapse. Adv Parasitol. 2012;80:113–150. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397900-1.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnadas C, Tichit M, Bouchier C, Ratsimbasoa A, Randrianasolo L, Raherinjafy R, Jahevitra M, Picot S, Ménard D. Plasmodium vivax dhfr and dhps mutations in isolates from Madagascar and therapeutic response to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. Malar J. 2008;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razakandrainibe R, Thonier V, Ratsimbasoa A, Rakotomalala E, Ravaoarisoa E, Raherinjafy R, Andrianantenaina H, Voahanginirina O, Rahasana TE, Carod JF, Domarle O, Ménard D. Epidemiological situation of malaria in Madagascar: baseline data for monitoring the impact of malaria control programmes using serological markers. Acta Trop. 2009;111:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]