Abstract

Interferon-beta (IFN-β) is a critical antiviral cytokine and is essential for innate and acquired immune responses to pathogens. Treatment with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) induces transient accumulation of IFN-β mRNA, which involves an increase and a decrease of IFN-β mRNA. This phenomenon has been extensively analyzed as a model for understanding the mechanisms of gene induction in response to external stimuli. Using a new RNA metabolic labeling method with ethynyluridine to directly measure de novo RNA synthesis and RNA stability, we reassessed both de novo synthesis and degradation of IFN-β mRNA. We found that transcriptional activity is maintained after the maximum accumulation of IFN-β mRNA following poly(I:C) treatment on immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells. We also observed an unexpected change in the stability of IFN-β mRNA before and after the maximum accumulation. The results indicate that this method of RNA metabolic labeling provides a general approach for the simultaneous analysis of transcriptional activity and mRNA stability coupled with transcriptional timing.

Keywords: Interferon-beta, poly(I:C), mRNA transcription, mRNA stability, ethynyluridine, metabolic labeling

Introduction

Changes in the dynamic levels of mRNA play a critical role in the physiology and pathology of our bodies. A typical example is interferon-beta (IFN-β), a cytokine that is involved in cellular responses and confers resistance to viral infections, enhances innate and acquired immunity and modulates cell survival and death [1]. The mechanisms of IFN-β gene expression have been extensively analyzed as a model for understanding the mechanisms of gene induction in response to external stimuli. Treatment of epithelial cells with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)) induces a transient increase and a rapid decrease of IFN-β mRNA. Poly(I:C) is recognized by toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5). Once recognized, the downstream transcription factor, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), is activated and induces the initial transcription of IFN-β. Induced IFN-β protein creates a positive feedback loop after IFN-β is recognized by IFN-β receptors on cell surfaces. IFN-β recognizing receptors activate a complex containing IRF9 to induce IRF7 expression, which in turn strongly induces IFN-β expression [1,2,3]. The transcriptional repressor of IFN-β, PRDI-BF1, which is induced by virus infection, probably represses transcription of IFN-β in response to poly(I:C) stimulation [4]. Shutoff of IFN-β gene expression involves not only transcriptional repression, but also a rapid degradation of IFN-β mRNA [5,6]. IFN-β mRNA has two major mRNA destabilizing elements, an AU-rich element (ARE) and a coding region instability determinant (CRID) [6,7]. ARE post-transcriptionally regulates the fate of various cytokine mRNAs, including IFN-β [8,9]. These previous studies have revealed both positive and negative feedback mechanisms of IFN-β gene transcription and mechanisms of IFN-β mRNA degradation; however, lack of methodologies for evaluating the rates of synthesis and degradation of RNA in vivo have hindered our understanding of the relationship between transcription and degradation.

In previous studies, nuclear run-on assays on isolated nuclei have been used to evaluate the rate of transcription; and study of the IFN-β gene has reported that its transcriptional activity parallels IFN-β mRNA accumulation [5]. Whether such a method can evaluate the transcription rate in vivo remains unclear. Analyses of RNA degradation have used transcriptional inhibitors such as actinomycin D and 5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB). However, these inhibitors cause global transcriptional arrest, disrupt cellular physiology [10,11] and interfere in the IFN-β mRNA degradation rate [5]. Therefore, transcriptional inhibitors cannot address dynamic settings in response to extracellular stimulation and cannot be combined with a nuclear run-on assay.

Recent methodological advancements in RNA metabolic labeling using various uridine analogs have provided an accurate measurement of transcriptional activity in physiological conditions in vivo [12,13,14]. RNA metabolic labeling also provides a method for analyzing the RNA degradation rate without interfering with transcription [11,15,16].

In this study we reassess the relationship between mRNA accumulation, transcriptional activity and mRNA stability of IFN-β after poly(I:C) treatment as a model system using a new RNA metabolic labeling method with ethynyluridine (EU) in physiological conditions.

Materials and methods

Cells, reagents and antibodies

Immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B TetOff) were generated as described previously [10]. BEAS-2B TetOff cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin. Poly(I:C) was purchased from InvivoGen. An anti-IFN-β ELISA Kit was purchased from PBL (#41410). Antibodies to IRF3 (#sc-9082, Santacruz), IRF7 (#3384-1, EPITOMICS) and IRF9 (#3467-1, EPITOMICS) were obtained commercially.

RT-PCR analysis

BEAS-2B Tet-Off cells (4.9 × 106/plate) were seeded on 10cm plates in DMEM medium. The cells were treated with 12μg of polyI:C and 30μl of polyethylenimine mixture in 1ml of PBS that was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. Two hours after polyI:C treatment, cells were washed twice with 10ml of PBS. Cells were harvested at the time-points indicated in the figures, and total RNA was purified using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized using a SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed by incubating the reverse transcribed product using a TaqMan Gene Expression Assays Probe (ABI) and qPCR Mastermix (Nippongene) with a iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Values were normalized to the 18S ribosomal RNA. Mean values ± standard error represent more than 3 independent experiments. The following probes were used: IFN-β (#Hs01077958_s1); MDA5 (#Hs00223420_m1); TLR3 (#Hs01551078_m1); IRF3 (#Hs01547283_m1); IRF7 (#Hs01014809_g1); IRF9 (#Hs00196051_m1); GAPDH (#Hs02758991_g1); and 18S rRNA (#4319413E).

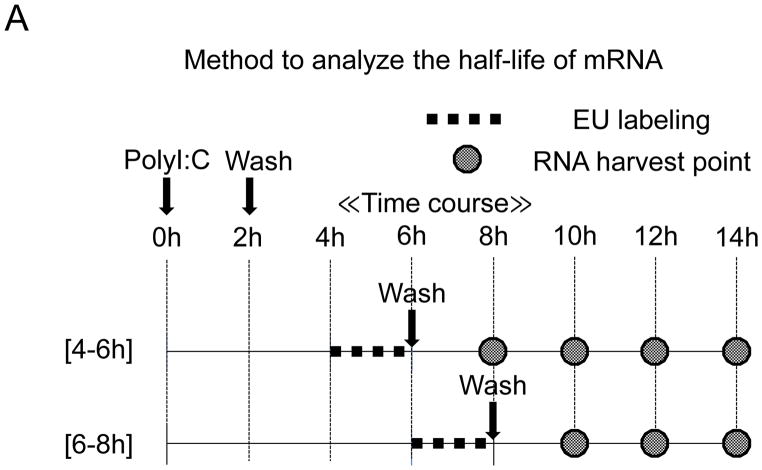

Metabolic labeling of RNA by 5-ethynyluridine

Metabolic labeling of RNA by EU for the analysis of de novo mRNA synthesis and mRNA half-lives was performed according to the Click-iT Nascent RNA Capture Kit (Life Technologies) manual. 200 μM of EU was added 2 hours before RNA extraction for the analysis of de novo mRNA synthesis. For mRNA half-lives, 100 μM of EU was added at 2 intervals, 4–6 hours or 6–8 hours, after poly(I:C) treatment. EU was washed out with PBS and fresh medium was added after 2 hours of RNA pulse metabolic labeling. qRT-PCR analysis was performed as described above. To avoid the effect of remaining in vivo EU, mRNA was analyzed 2 hours after EU removal. Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 (Life Technologies) was used for biotinated-RNA purification.

Results

Analysis of IFN-β gene expression induced by poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B cells

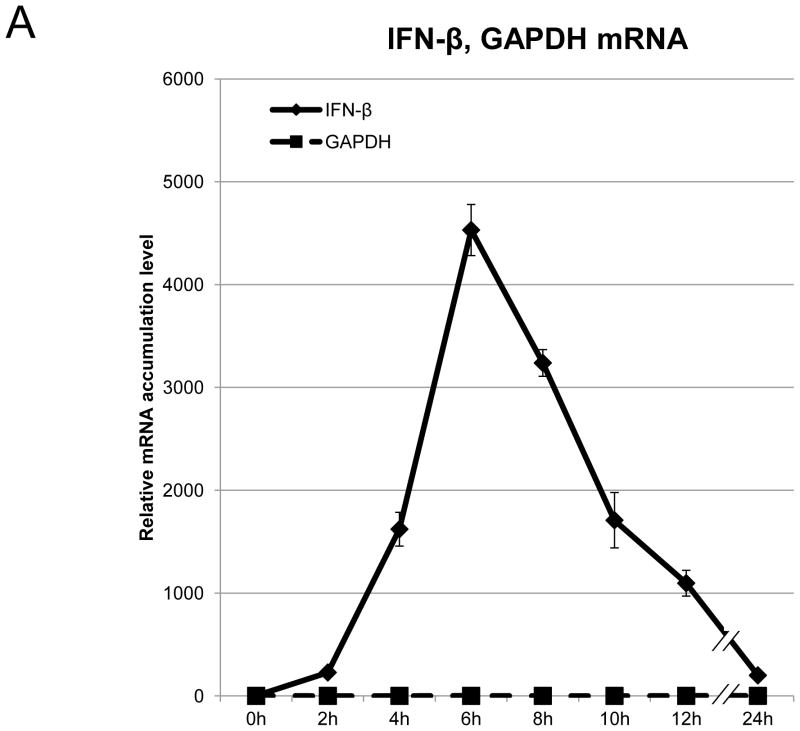

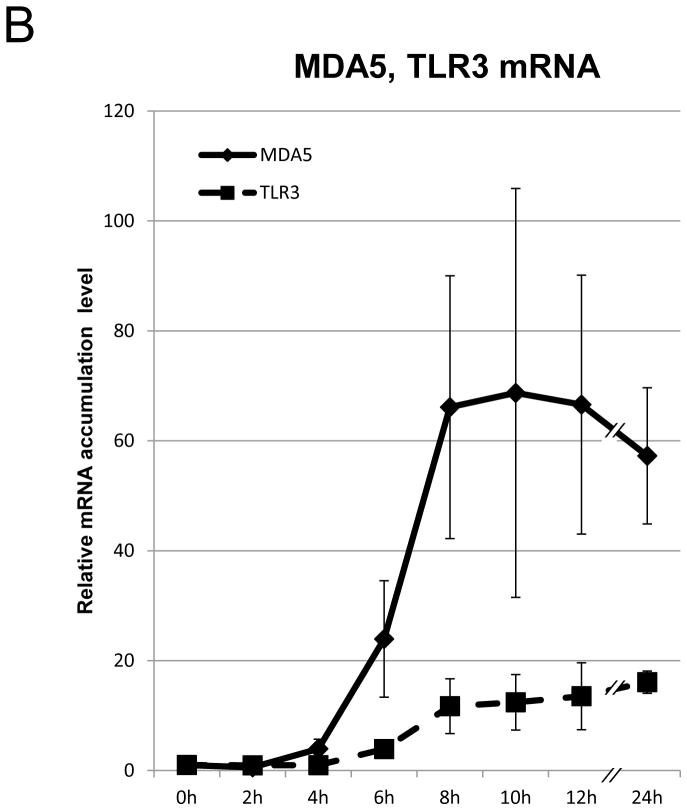

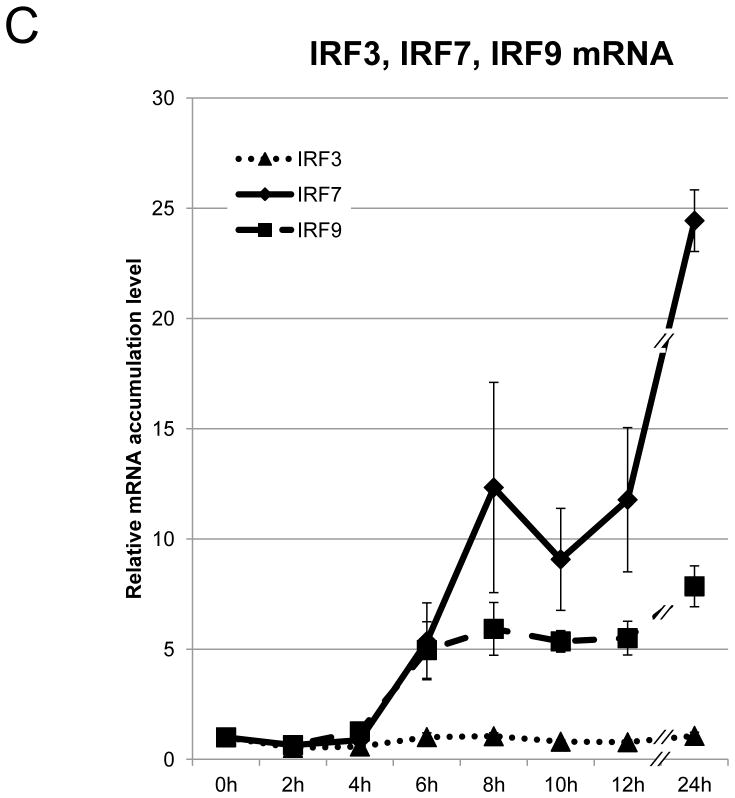

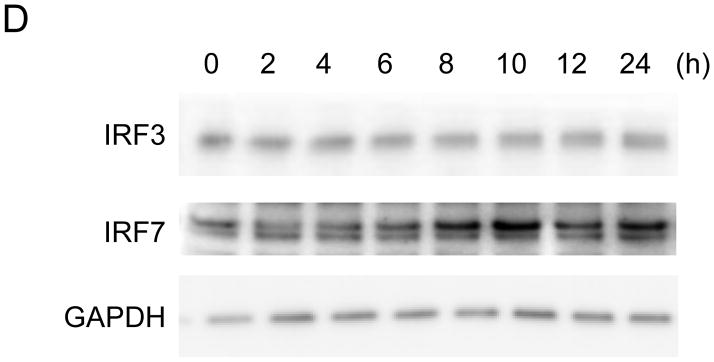

BEAS-2B cells are derived from normal human bronchial epithelial cells. They have frequently been used as a cellular model to study the role of bronchial epithelial cells in airway inflammation [17], and can induce IFN-β in response to poly(I:C) [18]. To reassess the kinetics of well-characterized IFN-β gene expression, we first performed a time course analysis of IFN-β mRNA accumulation in BEAS-2B cells following 2 hours of treatment with poly(I:C). Total RNA was collected at the indicated time-points after poly(I:C) treatment, and IFN-β mRNA accumulation was measured by qRT-PCR. IFN-β mRNA, normalized to18S rRNA, and showed an increase within 2 hours after poly(I:C) treatment. It reached a peak after 6 hours, after which, levels gradually decreased (Fig. 1A). The transcription of IFN-β mRNA is under positive feedback regulation [1]. As expected, the major cellular receptors of poly(I:C), TLR3 and MDA5 [2,3], the major downstream transcription factor of IFN-β, IRF9 [1,2,3], and the inducible IFN-β trans-activator, IRF7, were induced presumably in responses to secreted IFN-β as a positive feedback mechanism (Fig. 1B and 1C). To ensure that protein production of IRF7 responded to poly(I:C) treatment, we analyzed the protein expression of IRF7 on BASE-2B cells. IRF7 protein was induced 8 hours after poly(I:C) treatment, reached a peak after 10 hours, and subsequently decreased up to 24 hours (Fig. 1D). No apparent alternations were observed for IRF3, the control, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript (Fig. 1A) and protein (Fig. 1D). The expression of IRF7 protein, trans-activator of IFN-β, continued increasing (Fig. 1D), while expression of IFN-β mRNA decreased 8 hours after poly(I:C) treatment (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Poly(I:C) treatment induces IFN-β gene expression pathway.

(A–C) mRNA expression on BEAS-2B after poly(I:C) treatment. Poly(I:C) was washed out after 2 hours of treatment. Total RNA from BEAS-2B was purified at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 24 hours after poly(I:C) treatment. The relative mRNA levels of IFN-β [diamond, solid line] and GAPDH [square, dot line] (A), MDA5 [diamond, solid line] and TLR3 [square, dot line] (B), IRF7 [diamond, solid line], IRF9 [square, dot line] and IRF3 [triangle, dot line] (C) on BEAS-2B were determined by qRT-PCR, normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA. mRNA levels at time 0 were set to 1. Data was obtained through triplication of 3 experiments. Results are shown as the means ± standard error. (D) Poly(I:C) treatment induces IRF7 protein expression. Cell lysate was collected at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 24 hours after poly(I:C) treatment. Poly(I:C) was washed out after 2 hours of treatment. Lysates were analyzed using the antibodies indicated.

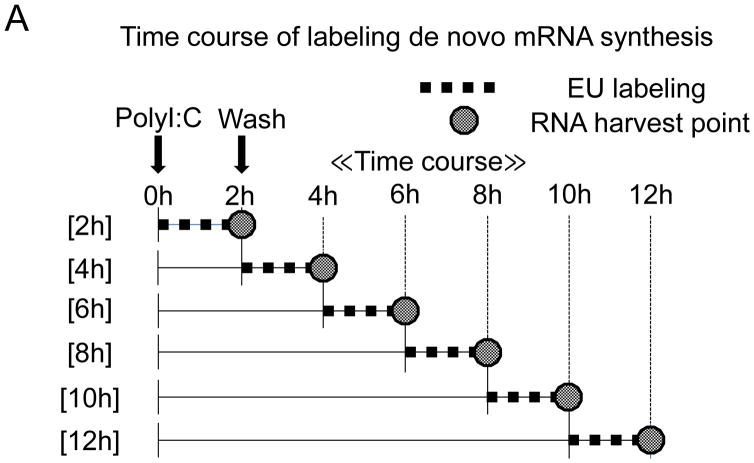

Analysis of de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA induced by poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B cells

Although a previous study has demonstrated identical kinetics of IFN-β mRNA accumulation and nuclear transcription measured by an in vitro nuclear run-on assay [5], it could not explain the observed expression discrepancy of IFN-β mRNA and its transcriptional activator, IRF7 protein. To clarify the mechanism of this discrepancy we re-examined the de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA induced after poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B cells. To achieve this, we adapted a chemical method to detect RNA synthesis in cells, based on the biosynthetic incorporation of the uridine analog 5-ethynyluridine (EU) into newly transcribed RNA [13]. Metabolic labeling methods can precisely monitor the de novo synthesis of newly transcribed RNA during labeling in vivo [12,13,14].

BEAS-2B cells were labeled with EU for 2 hours prior to harvest at the indicated time points after poly(I:C) treatment (Fig. 2A). After RNA purification, EU-labeled de novo synthesized RNA was biotinylated using a copper (I)-catalyzed cycloaddition reaction with PEG4 carboxamide-6-azidohexanyl biotin. Biotinylated de novo synthesized RNA was then collected by streptavidin dynabeads and analyzed by qRT-PCR. No noticeable cell toxicity was observed by EU pulse-labeling for 2 hours on BEAS-2B cells. Also, compared with non-EU labeling (Fig. 1A), no significant alternations in IFN-β expression patterns were observed by RNA metabolic labeling using EU (Supplementary Fig. S1). This indicates that EU labeling did not have a major influence on IFN-β mRNA expression.

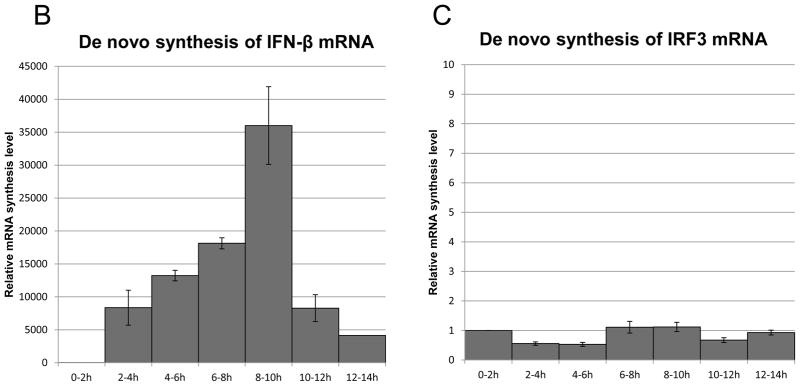

Figure 2. De novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA after poly(I:C) treatment.

(A) Flowchart illustrating the analysis of de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA using EU on BEAS-2B after poly(I:C) treatment. (B and C) Total RNA was extracted at the time-points indicated after 2 hours of mRNA metabolic labeling. EU-labeled RNA was collected using streptavidin dynabeads after biotination. The relative mRNA abundance, normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA, was then analyzed by qRT-PCR for IFN-β (B) or IRF3 (C). IFN-β and IRF3 mRNA levels at time 0 were set to 1. Data was obtained through triplication of 3 experiments. Results are shown as the means ± standard error.

As shown in Figure 2B, de novo synthesis or transcription of IFN-β mRNAs appeared 2–4 hours after poly(I:C) treatment, reached a peak after 8–10 hours, and subsequently dropped after 10–12 hours. No significant differences were observed for the de novo synthesis or transcription of control IRF3 mRNA (Fig. 2C). The results indicate that transcription of IFN-β mRNA continues even after the peak of mRNA accumulation, and is similar to IRF7 protein accumulation. The results also show that EU can be an effective method for analyzing transcriptional activity.

Analysis of the stability of IFN-β mRNA induced by poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B cells

We hypothesized that IFN-β mRNA became unstable 6 hours after poly(I:C) treatment, while its transcription remained unchanged. Previous studies analyzing IFN-β mRNA stability were performed by blocking cellular transcription with the inhibitor actinomycin D [10,11]. This method suffers from the disadvantage that actinomycin D has a profound impact on cellular physiology and has been shown to alter the stability of IFN-β mRNA [5], and cannot be combined with the analysis of transcriptional activity. RNA metabolic labeling using EU provided not only a method for the accurate measurement of mRNA de novo synthesis, but also for the analysis of mRNA stability without affecting transcription using the same method.

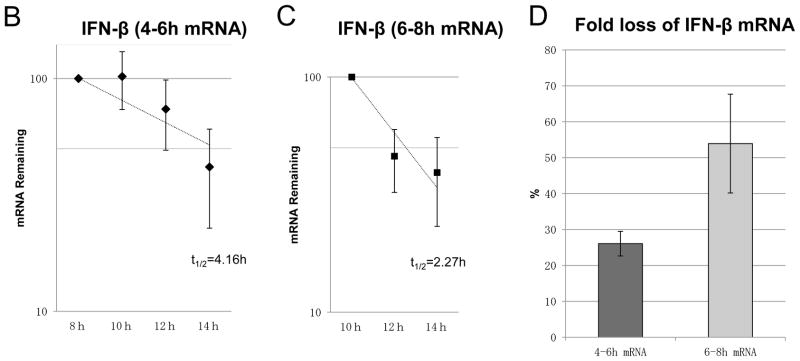

To determine IFN-β mRNA stability, we pulse-labeled RNA with EU for 2 hours at intervals of 4–6 hours after poly(I:C) treatment. Following EU removal, cells were collected at different times. Remaining EU-labeled mRNA was analyzed as a function of time by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3A). The half-life of IFN-β mRNA, pulse-labeled by EU for 2 hours at 4–6 hour interval was t1/2 4.16 hours (Fig. 3B). Such stability of INF-β mRNA cannot explain the rapid disappearance of IFN-β mRNA (Fig. 1A), given that there is continuous de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA (Fig. 2B).

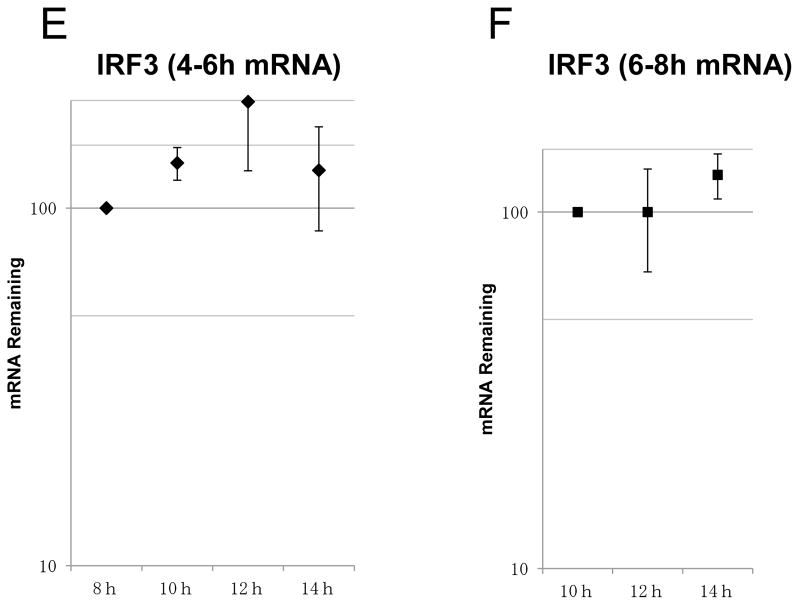

Figure 3. Half-life analysis of EU-labeled IFN-β mRNA after poly(I:C) treatment.

(A) Flowchart illustrating the analysis of the half-life of IFN-β mRNA using EU on BEAS-2B after poly(I:C) treatment. After poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B, EU was added to BEAS-2B at 2 intervals, 4–6 hours (B and E) or 6–8 hours (C and F). EU was washed out with PBS and fresh medium added after 2 hours of RNA pulse metabolic labeling. Total RNA was extracted at the time-points indicated. Remaining EU-labeled RNA was collected using streptavidin dynabeads after biotination. The relative remaining mRNA abundance, normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA, was then analyzed by qRT-PCR for IFN-β (B and C) or IRF3 (E and F). Data was obtained through triplication of 2 experiments. Results are shown as the means ± standard error. (D) Fold loss of labeled IFN-β mRNA at 10–12 hours, synthesized at either 4–6 or 6–8 hour intervals.

Because pulse-labeling of RNA by EU at 4–6 hours after poly(I:C) treatment was the time-point at which IFN-β mRNA expression and de novo synthesis increased, we assumed that the stability of de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA was determined at the time of transcription. In other words, IFN-β mRNA transcribed at later times may become much more unstable than at the 4–6 hour interval. To assess this possibility, we analyzed the half-life of IFN-β mRNA, pulse-labeled by EU at the 6–8 hour interval—the time-point when decreasing expression of IFN-β mRNA was observed (Fig. 3A). The results support the notion that the half-life of IFN-β mRNA, pulse-labeled by EU at 6–8 hours, was shorter (Fig. 3C; t1/2 2.27 hours) than that at 4–6 hours. It is worth noting that IFN-β mRNA transcribed at 4–6 hours was more stable than IFN-β mRNAs transcribed at 6–8 hours, even when decay was followed at the 10–12 hour interval after poly(I:C) treatment (Fig. 3D). No significant alternations were observed for the stability of the control, IRF3 mRNA, between the time-points of pulse-labeling (Fig. 3E and 3F). Collectively, these results show that the intrinsic stability of IFN-β mRNA changes during the time course of poly(I:C) treatment, which seems to depend on the time when it is transcribed.

Discussion

In this study we analyzed the de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA by RNA metabolic labeling using EU (Fig. 2). Using RNA metabolic labeling for kinetic analysis of the accumulation and de novo synthesis of IFN-β mRNA, we unexpectedly revealed that decreasing transcriptional activity of IFN-β occurs more than 2 hours after the maximum accumulation of IFN-β mRNA in response to poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 1A and 2B). These results are different from a previous study, which showed virtually identical kinetics of IFN-β mRNA accumulation and nuclear transcription measured by a nuclear run-on assay [5]. Intriguingly, a strong correlation between the transcriptional activity of IFN-β mRNA and the accumulation of IRF7 protein was observed (Fig. 1A and 1D). Such results are consistent with our current understanding. The IRF3 homo-dimer, and possibly the IRF3:IRF7 hetero-dimer, initiate early phase IFN-β transcription. Newly secreting IFN-β then induces IRF7 induction for robust IFN-β transcription in response to poly(I:C) treatment [1,19]. The high transcriptional activity of IFN-β during decreased expression might be mediated by IRF7.

By using RNA pulse-labeling with EU, we observed that IFN-β mRNA transcribed at times when accumulation is increasing is more stable compared with IFN-β mRNA transcribed at later times when accumulation is decreasing (Fig. 3A–3C). The stability of earlier transcripts is more stable than later transcripts, even in the same time frame (Fig. 3D). IFN-β mRNA destabilization factor(s) might newly synthesize and degrade IFN-β mRNA, as is reported in TNFα [20] and IL6 [21]. It is possible that transcriptional timing determines the destiny of IFN-β mRNA stability. Further study is required to clarify the precise mechanisms and regulation of IFN-β in response to poly(I:C) treatment. Our results revealed that decreasing expression levels of IFN-β mRNA were initially caused by the instability of newly transcribed products, but not by the destabilization of IFN-β mRNA transcribed at the time when its expression was still increasing, followed by a decrease in transcriptional activity.

In conclusion, using a new RNA metabolic labeling method with EU, we demonstrate that the robust transcriptional activity of IFN-β continues after the peak of its mRNA accumulation following activation by poly(I:C) treatment on BEAS-2B cells. Additionally, we reveal the possibility that the stability of IFN-β mRNA depends on the time of synthesis. RNA metabolic labeling by EU is a useful tool to investigate the relationship between transcriptional activity, accumulation and stability for individual gene expression in a unified technique.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kazunori Sasaki at our laboratory and Mr. Takayuki Shirakawa at the Department of Histology and Cell Biology, Y.C.U. for their technical assistance with qRT-PCR and ELISA. We also thank Dr. Mitsutoshi Yoneyama and Dr. Koji Onomoto at Chiba University for their reading of this manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research [A] (to S.O.), Young Scientists [A] (to A.Y.), Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “RNA regulation” (to A.Y.) and Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Functional machinery for noncoding RNAs” (to A.Y.), Takeda Science Foundation (to S.O. and to A.Y.), and National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (to A.B.S.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

K.A. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the article; A.Y. conceived and designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the article; A.-B.S. provided the cell line, comments on the study, and preparation of the article; T.I., S.O., and S.U. supervised the project and participated in the preparation of the article.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Kaito Abe, Email: kaitoabe@yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

Tomoaki Ishigami, Email: tommmish@med.yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

Ann-Bin Shyu, Email: Ann-Bin.Shyu@uth.tmc.edu.

Shigeo Ohno, Email: ohnos@med.yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

Satoshi Umemura, Email: umemuras@med.yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

Akio Yamashita, Email: yamasita@yokohama-cu.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Borden EC, Sen GC, Uze G, Silverman RH, Ransohoff RM, Foster GR, Stark GR. Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:975–990. doi: 10.1038/nrd2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor and RIG-I-like receptor signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:1–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoneyama M, Onomoto K, Fujita T. Cytoplasmic recognition of RNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:841–846. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren B, Chee KJ, Kim TH, Maniatis T. PRDI-BF1/Blimp-1 repression is mediated by corepressors of the Groucho family of proteins. Genes Dev. 1999;13:125–137. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittemore LA, Maniatis T. Postinduction turnoff of beta-interferon gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1329–1337. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj NB, Pitha PM. 65-kDa protein binds to destabilizing sequences in the IFN-beta mRNA coding and 3′ UTR. Faseb J. 1993;7:702–710. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.8.8500695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paste M, Huez G, Kruys V. Deadenylation of interferon-beta mRNA is mediated by both the AU-rich element in the 3′-untranslated region and an instability sequence in the coding region. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:1590–1597. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CY, Shyu AB. Mechanisms of deadenylation-dependent decay. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011;2:167–183. doi: 10.1002/wrna.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schott J, Stoecklin G. Networks controlling mRNA decay in the immune system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2010;1:432–456. doi: 10.1002/wrna.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CY, Yamashita Y, Chang TC, Yamashita A, Zhu W, Zhong Z, Shyu AB. Versatile applications of transcriptional pulsing to study mRNA turnover in mammalian cells. Rna. 2007;13:1775–1786. doi: 10.1261/rna.663507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tani H, Mizutani R, Salam KA, Tano K, Ijiri K, Wakamatsu A, Isogai T, Suzuki Y, Akimitsu N. Genome-wide determination of RNA stability reveals hundreds of short-lived noncoding transcripts in mammals. Genome Res. 2012;22:947–956. doi: 10.1101/gr.130559.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westaway EG, Khromykh AA, Mackenzie JM. Nascent flavivirus RNA colocalized in situ with double-stranded RNA in stable replication complexes. Virology. 1999;258:108–117. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jao CY, Salic A. Exploring RNA transcription and turnover in vivo by using click chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15779–15784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabani M, Levin JZ, Fan L, Adiconis X, Raychowdhury R, Garber M, Gnirke A, Nusbaum C, Hacohen N, Friedman N, Amit I, Regev A. Metabolic labeling of RNA uncovers principles of RNA production and degradation dynamics in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:436–442. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolken L, Ruzsics Z, Radle B, Friedel CC, Zimmer R, Mages J, Hoffmann R, Dickinson P, Forster T, Ghazal P, Koszinowski UH. High-resolution gene expression profiling for simultaneous kinetic parameter analysis of RNA synthesis and decay. Rna. 2008;14:1959–1972. doi: 10.1261/rna.1136108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munchel SE, Shultzaberger RK, Takizawa N, Weis K. Dynamic profiling of mRNA turnover reveals gene-specific and system-wide regulation of mRNA decay. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2787–2795. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takizawa H, Ohtoshi T, Kawasaki S, Abe S, Sugawara I, Nakahara K, Matsushima K, Kudoh S. Diesel exhaust particles activate human bronchial epithelial cells to express inflammatory mediators in the airways: a review. Respirology. 2000;5:197–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li YG, Siripanyaphinyo U, Tumkosit U, Noranate N, Pan ANAY, Kameoka M, Takeshi K, Ikuta K, Takeda N, Anantapreecha S. Poly (I:C), an agonist of toll-like receptor-3, inhibits replication of the Chikungunya virus in BEAS-2B cells. Virol J. 2012;9:114. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N, Taniguchi T. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Ikeda K, Maezawa Y, Suto A, Takatori H, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. IL-4-Stat6 signaling induces tristetraprolin expression and inhibits TNF-alpha production in mast cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1717–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsushita K, Takeuchi O, Standley DM, Kumagai Y, Kawagoe T, Miyake T, Satoh T, Kato H, Tsujimura T, Nakamura H, Akira S. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature. 2009;458:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature07924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.