Abstract

Study objective

To describe and explore provider- and patient-level perspectives regarding long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for teens and young adults (ages 16-24).

Methods

Data collection occurred between June – December 2011. We first conducted telephone interviews with administrative directors at 20 publicly funded facilities that provide family planning services. At six of these sites, we conducted a total of six focus group discussions (FGDs) with facility staff and forty-eight in-depth interviews (IDIs) with facility clients ages 16-24.

Results

Staff in the FGDs did not generally equate being a teen with ineligibility for IUDs. In contrast to staff, one quarter of the young women did perceive young age as rendering them ineligible. Clients and staff agreed that the “forgettable” nature of the methods and their duration were some of LARC’s most significant advantages. They also agreed that fear of pain associated with both insertion and removal and negative side effects were disadvantages. Some aspects of IUDs and implants were perceived as advantages by some clients but disadvantages by others. Common challenges to providing LARC-specific services to younger patients included extra time required to counsel young patients about LARC methods, outdated clinic policies requiring multiple visits to obtain IUDs, and a perceived higher removal rate among young women. The most commonly cited strategy for addressing many of these challenges was securing supplementary funding to support the provision of these services to young patients.

Conclusion

Incorporating young women’s perspectives on LARC methods into publicly funded family planning facilities’ efforts to provide these methods to a younger population may increase their use among young women.

Keywords: long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), young adults, adolescents, unplanned pregnancy, teen pregnancy, contraception

Introduction

Approximately half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended,1 which are associated with adverse health outcomes for both mothers and children.2 This public health challenge is greatest among teens and young adults, as 18-19 year-olds and 20-24 year-olds have the highest rates of unintended pregnancy among sexually active individuals.3 Given that 43% of unintended pregnancies result from incorrect or inconsistent use of contraception,4 increasing the use of more effective, long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARCs), such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants, could reduce rates of unintended pregnancy.5,6 Because LARCs require only a single act of insertion for long-term use and are independent from user motivation and adherence, their typical use failure rates (<1%) are significantly lower than those of more commonly used methods such as oral contraceptives (8%) and condoms (15%).7,8 However, while the proportion of women of reproductive age using LARC methods has more than tripled in recent years, overall use remains low (9%).9 Moreover, despite the fact that these methods may be particularly ideal for younger women, most of whom report desires to delay initial childbearing for several years,10,11 teens have the lowest LARC usage rates (4%) of any age group.12

Although practice guidelines are changing to reflect the demonstrated safety and efficacy of LARC methods for teens and young adults, including those with no children,13-15 approximately one-third to one-half of providers, including obstetrician gynecologists, family medicine physicians, physician assistants and nurses, believe that IUDs are not an appropriate method for nulliparous women, and nearly two-thirds do not view teens as suitable IUD candidates.16-18 Other clinician misconceptions about IUDs that may influence the provision of these methods to young women include beliefs that they increase the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and that they are inappropriate for patients in non-monogamous relationships or who have a history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).16-19

Young women’s knowledge and attitudes about LARC methods also serve as barriers to their use.20-24 Studies have shown that between 50% and 60% of young women have never heard of the IUD,20,22-24 while over 90% have no knowledge about implants.22 Moreover, research suggests that the accuracy of knowledge among young women who have heard of these methods is low. In one study, 71% of young women reported being unsure of the safety of IUDs, while 58% were unclear about their efficacy.23 Another study found that many young women felt that LARCs were not appropriate methods for teens and erroneously believed that they were associated with infection and infertility.22

Our research builds on a recent nationally representative survey of over 1,200 publicly funded facilities providing family planning services, which serve a disproportionately high number of younger-age clients in the United States.25 Findings from the survey indicated that certain types of facilities, particularly Planned Parenthood affiliates, were much more likely than other types of facilities to report increases in LARC use among teens and young adults over the past two years and to make IUDs and implants more accessible to interested patients by more frequently having the devices available onsite for insertion.26 The most common challenges to providing LARCs to young clients identified in the survey included cost and reimbursement issues (60% of sites) and staff attitudes about IUD use in teens (47%), non-monogamous women (44%), and nulliparous women (40%).26

The objectives of our research were (1) to explore and compare provider and patient perspectives about LARC methods for young women and (2) to examine and identify strategies for addressing challenges experienced by facility staff in providing LARC methods to young women. The current study uses qualitative methods—which are especially suited for exploring attitudes, examining how beliefs affect behaviors, and providing more detailed understandings of people’s experiences27-29—in order to delve deeper into patterns of, and challenges to, LARC provision identified in the survey. In addition, this study incorporates the unique voices of young women receiving contraceptive services to complement provider perspectives. The results of the study will help to identify ways in which publicly funded facilities that provide family planning can improve their LARC services to better meet the contraceptive needs of sexually active teens and young adults in the United States.

Methods

Sample and data collection

Data come from three sources: 20 semi-structured telephone interviews with administrative directors at publicly funded sites that provide family planning services, 6 focus group discussions (FGDs) with a total of 37 facility staff, and 48 semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDIs) with clients 16-24 years of age. We used the 2009 Family Planning Annual Report, which provides national-level data on the Title X Family Planning Program, to help us identify Title X grantees that documented high (>6%) and low (<2%) percentages of LARC (IUD and implant) provision among young women. From the 44 grantees that met these criteria, out of the total universe of 89 grantees, we contacted the administrative directors at ten grantees (5 in each grantee group) that represented diversity in geographic location and grantee type (Planned Parenthoods, health departments and family planning councils). We asked each grantee to identify two to three health facilities among their funded sites that represented the same trends in LARC provision among women ages 16-24 that were documented at the grantee level.

Director interviews

We conducted approximately hour-long telephone interviews with administrative directors at 20 facilities, split evenly between facilities with higher and lower levels of LARC provision to young women. We asked directors about levels of LARC provision to teens and young adults at their sites to confirm whether their provision trends matched those at the grantee level. The semi-structured director interview guide asked respondents about LARC-related practices, including facility policies and protocols regarding provision of IUDs and implants to teens and young adults, workforce and training issues and needs, trends in LARC use among young patients, counseling/education practices, and perceived barriers to providing LARCs to young women.

Staff focus group discussions

From the 20 sites at which director interviews were conducted, we selected six (three with higher and three with lower levels of LARC use among young women) across the country that had different service delivery models (e.g. health department clinics, stand-alone family planning centers and adolescent-specific clinics) at which to conduct staff FGDs and client IDIs. We coordinated with a staff liaison at each site to recruit staff participants who were not in supervisory or subordinate positions to one another for each focus group; participants included clinicians, educators, medical assistants, and receptionists. All groups had between five and eight participants, were held either before or after work hours to minimize disruption of the clinic flow, and were approximately 90 minutes long. Each focus group was facilitated by a member of the research team while another team member took notes. Facilitators used a guide that queried participants about LARC trends among young patients, their attitudes about young women using IUDs and implants, and perceived barriers to providing LARC services to these younger patients.

Client in-depth interviews

Across the six sites at which staff focus groups were held, we conducted a total of 48 in-depth interviews with 22 adolescents (ages 16-19) and 26 young adult (ages 20-24) clients, evenly split between high and low sites. Eligible respondents were female, English-speaking clients between ages 16 and 24 who were visiting the site for family planning services during a second or supplemental visit. Research staff coordinated with clinic staff to recruit and interview interested and eligible respondents. All interviews were conducted by a member of the research team, took place after the respondents’ appointments in a private location within the clinic settings, and lasted approximately one hour. The IDI guide, pretested with four clients aged 16-24 at a local family planning clinic, included questions about respondents’ knowledge of, experiences with, and attitudes about IUDs and implants and their needs with regards to receiving these methods. At the conclusion of the interview, respondents were asked to fill out a short questionnaire on their socio-demographic characteristics.

Director interviews took place between June and August of 2011 and the FGDs and IDIs were conducted between September and December 2011. All participants received a component-specific study description, gave informed consent (minors 16 and 17 provided assent for the IDIs) and were paid for their participation ($75 for the director interviews, $50 for the FGDs and $40 for the IDIs). Participation in each component of the study was conditional on the interview or FGD being audio-recorded. This study and all associated procedures and study instruments were approved by the federally registered Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the PI’s organization. The director interviews were considered to be exempt from review because questions focused on facility services and policies, not personal opinions or attitudes.

Data management and analysis

Recordings from each of the three components were transcribed verbatim and identifying information was stripped during the cleaning phase. For the FGDs, we organized participant responses according to themes directly related to questions from the FGD guide. For the director interviews and client IDIs, we developed initial coding schemes prior to data collection based on the interview guides and existing literature and subsequently adapted and updated the schemes throughout the interview and coding processes. Three members of the research team independently double-coded three director interview transcripts and three client interview transcripts and then examined inter-coder reliability, which initially ranged from 76-100% agreement. We resolved code divergence through discussion and the development of new codes. After further double-coding, subsequent examination of inter-coder reliability ranged from 95-100%, and all remaining transcripts were coded by at least one member of the research team. We used NVivo 8 to organize the data, code transcripts, and generate code reports.

Following Miles & Huberman30, as a preliminary step to identify the most prevalent ideas, we counted the number of transcripts in which common codes or themes appeared. This pointed us to areas that potentially deserved additional attention. We then further analyzed the data by summarizing emerging themes and concepts and exploring patterns of similarity and difference, with a particular eye toward differences between high and low utilization sites and teens and young adults. Key topics that emerged are summarized via a textured description and illustrated using direct quotes from participants.31 Due to the substantive differences between the group dynamic present in FGDs and the one-on-one format of an IDI, we used the FGD as the unit of analysis to compare to individual respondents to the IDIs.32 We used LARC provision at the facility level in our analyses. Where contrasts emerged between sites with higher and lower levels of LARC use, teens and young adults, or patients and providers, we note them; otherwise, we weave the responses together.

We first present knowledge of, and experiences with, LARC methods among clients to orient readers to the subsequent sections on attitudes. Next, we use data from the FGDs and client IDIs to compare staff attitudes about young women using LARC methods to clients’ own perspectives. We then present opinions about the pros and cons of LARC methods for young women from the perspectives of staff and clients. Finally, we use the director interviews and FGDs to present providers’ perspectives on, and strategies for addressing, challenges they face in providing LARC methods to young women.

Results

Demographics of clinic and client samples

Of the twenty sites at which director interviews were conducted, six were Planned Parenthood affiliates, three were federally qualified health centers, three were health departments, two were hospitals, and six were some other type of facility. The six sites at which FGDs and IDIs were conducted included two health departments, one hospital, one Planned Parenthood affiliate, and two other types of sites.

Among the 48 client respondents, just over half were young adults aged 20-24 (54%), and 46% were teens aged 16-19. Nearly half (46%) of the clients were below 100% of the poverty level, and most of the rest (35%) were low-income (100-199% of the poverty level). Forty percent of clients in the sample were white non-Hispanic, 19% were black non-Hispanic, 35% were Hispanic (of various races), 8% were of mixed or other races, and 2% did not identify a race or ethnicity. One teen had previously given birth compared to ten young adults who reported one or more past births.

Clients Knowledge of IUDs and implants among young women

Eight of the 48 clients reported having used the IUD, while three had used the implant. Most women interviewed had at least some knowledge about IUDs and/or implants, though this varied by age group and whether they were interviewed at a site with higher or lower levels of LARC provision. About one quarter of teens stated that they had no knowledge of the IUD or the implant, compared to only one young adult who knew nothing about the IUD and seven who knew nothing about the implant. Among clients with some knowledge about LARC methods, the most commonly known topics included potential side effects, insertion site/location within the body, method duration, and effectiveness. Young adults more frequently described accurate, detailed information about insertion site/location and side effects than teens. In the context of relaying others’ experiences with LARC methods, clients often mentioned menstruation-related side effects, such as how the method would change or stop one’s period.

Staff and clients: Attitudes about candidacy for IUDs and implants

Staff conversations concerning LARC candidacy included discussion of certain subgroups of women who have traditionally been considered ineligible for IUDs, including teens, non-monogamous women, and women who have never given birth. Staff did not generally equate being a teen in and of itself with ineligibility; instead, characteristics associated with teenage behavior, such as having multiple partners, concerned them. In two of the focus groups at sites with higher levels of LARC provision, some staff considered young women who had never given birth to be ineligible for IUDs due to their smaller reproductive anatomy. Staff did, however, identify other subgroups of young women, such as college-aged women and women in the military, as ones who would especially benefit from the long-acting nature of IUDs and implants.

In contrast to staff, one quarter of the young women did perceive young age as rendering them ineligible for IUDs, describing this method as “more serious” and often citing media portrayals of “typical” users as older women seeking to limit their family size. Nine young women at sites with lower levels of LARC provision talked about age-related candidacy criteria compared to three young women at higher sites.

I think [the IUD is] more for women who’ve already had children and don’t really want to have more kids, and are just waiting for menopause. I think it’s more for, like, women in their 30’s and 40’s [client IDI43, teen, higher LARC provision site].

A few young women specifically identified having given birth as a perceived necessary criterion for IUD candidacy, but none brought up monogamy. Neither staff nor young women expressed concrete ideas about candidacy for implants or characteristics that would make a person ineligible for them that were distinct from IUDs.

When asked what they thought about young women their age using IUDs and implants, three quarters of clients mentioned a positive, lifestyle-related aspect of at least one of the methods. Nine young adult clients and six teens indicated that young women’s busy, hectic lives made them ideal candidates for IUDs and/or implants because these methods were long-acting and easy to forget about post-insertion.

I think [IUDs and implants] are good for women my age because I think we all have 5000 things on our plate. Women my age are going to grad school and working full time and thinking about starting commitments … that the day to day can slip right by. And so things like pills or…any other form of birth control that requires you to have any sort of planning in advance, that’s always inconvenient, so I think we’re just…young and probably stupid most of the time and making decisions on the fly and something like that, where it’s just done taken care of, check that off the list and move on with life, that’s probably good [client IDI35, young adult, lower LARC provision site].

Another popular client sentiment was that their strong desire to avoid pregnancy rendered them ideal candidates for IUDs and implants due to their high efficacy. This was more commonly mentioned by clients at higher-provision than lower-provision sites (nine vs. five) and among young adults (nine vs. five teens).

Staff and clients: Pros and cons of IUDs and implants

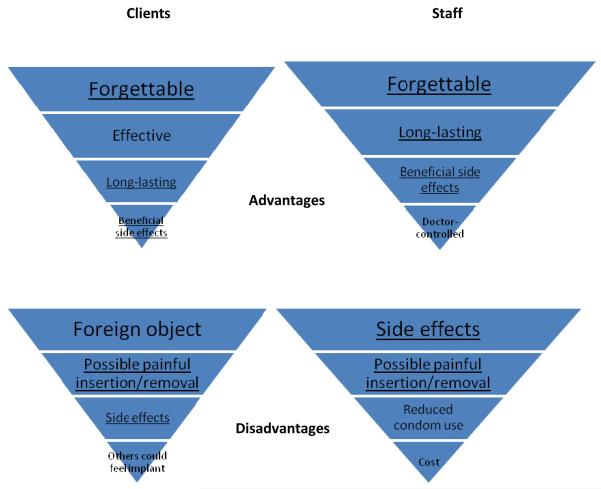

Staff and clients alike identified several common advantages and disadvantages to young women using IUDs and implants (Figure 1). Most of these were applicable to both types of longer-acting methods; as such, the figure represents advantages and disadvantages grouped for IUDs and implants.

Figure 1.

Client and staff perspectives on advantages and disadvantages of LARC methods, listed in descending order from most to least common within groups. Top four characteristics mentioned in client IDIs and staff FGDs are presented. Underlined characteristics represent agreement between clients and staff.

Clients and staff agreed that the “off one’s mind” or “forgettable” nature of the methods and their duration were among the most significant advantages to young women using LARCs. Clients emphasized the effectiveness of LARC methods to a greater extent than did staff, while staff placed more emphasis on their beneficial side effects and discreet nature. Clients and staff agreed that fear of pain associated with both insertion and removal and negative side effects were disadvantages of LARC methods for young women. Clients placed greater emphasis on the disadvantage of having a foreign object in one’s body and the possibility that they or others could either see or feel the implant, while staff were more concerned about cost issues and the possibility that LARCs might reduce condom use among younger users. Staff from four sites also indicated a concern that they would lose opportunities to intervene in other health issues, especially STIs, with their young patients who chose the longer-acting methods because they might not return to the clinic for the duration of the method’s coverage. Examining differences by clients’ age, young adult clients cited more advantages to using LARC methods than did teens, particularly beneficial side effects, reversibility, and cost effectiveness. Teens more frequently mentioned the discreet nature of LARC methods as an advantage.

Some aspects of IUDs and implants were perceived as advantages by some clients but disadvantages by others. For example, the long-acting nature of IUDs and implants was seen as a positive by young women who wanted to delay childbearing for several years, while others felt that 5-10 years for the IUD, and even three years for the implant, was too long for them to consider.

I mean if you’re getting something inserted, the one that lasts longer would be more appealing to me [client IDI43, teen, higher LARC provision site]

Three years does not sound as bad as 5, I would probably be willing to try that. […] Again I don’t know why it’s so shockingly different when it’s essentially the same idea but for whatever reason, 3 more years seems way more reasonable than 5 to me, again because I’m anti committal, shorter time [client IDI35, young adult, lower LARC provision site]

Similarly, some young women looked favorably upon the menstrual suppression associated with the hormonal IUD, but this was perceived as a downside by others, including some Latina clients who cited cultural beliefs about the harmful effects of not getting a regular period. In addition, some respondents identified LARC methods as being cost effective over the duration of their use, while others indicated that the high upfront costs associated with obtaining them was prohibitive. Finally, the necessity of having LARC methods inserted and removed by a doctor appealed to some respondents because it took control out of their hands, yet others disliked this lack of control and inability to discontinue the method without visiting a clinic.

Select concerns led respondents to favor one LARC method over another. Staff and directors expressed both more concerns about IUD use and a stronger preference for implants for younger women. Many felt that IUDs posed more clinical and logistical challenges, including difficulty dilating the cervices of nulliparous women and/or placing the device in a small uterus, managing clinic flow around the lengthy IUD insertion visit, and maintaining adequate staffing in the face of possible complications from insertion. FGD participants from five sites felt that IUDs are not good methods for young women because they are not comfortable reaching into their vaginas to regularly check the strings. In contrast, staff in five of the FGDs felt that the location and ease of insertion associated with the implant rendered it a particularly appropriate method for young women.

I think a lot of teenagers in that age group, like the 15 [year olds] or so, I think they mention that they want the Implanon more so than an IUD. So I’m not too sure they are feeling more comfortable or if they know a teen that had it or because it’s in the arm and not in the vagina [staff FGD 6, higher LARC provision site].

Despite the many disadvantages cited regarding the IUD for young women, clinicians were not unified in their preference for implants. The side effect profile of the hormonal IUD was cited as an advantage by staff in all six FGDs, who mentioned a patient’s tolerance for irregular bleeding as the main criterion for whether to recommend the implant. They revealed differing opinions on whether this criterion was met by teenaged patients, however, as some participants in each FGD indicated that teens’ propensity to be less tolerant of side effects led them to discontinue the use of LARC methods, especially implants, at a higher rate than older women.

I just wish they were a little bit more open minded and a little bit more patient with possible side effects. I mean you have these young women that will go and chop off their hair and if they don’t like it they’ll think to themselves oh, it will grow back, but with birth control if like two days later they are having bleeding they call right away and they are like I want this taken out right now [staff FGD 6, higher LARC provision site].

Clinicians also perceived greater fear among their younger patients regarding the insertion of the implant versus an IUD.

Overall, 21 clients expressed a preference for one of the LARC methods over the other; of these, 13 favored the implant while eight favored the IUD. In terms of the insertion of each method, 11 felt that the IUD process sounded better compared to eight who felt they would prefer that of the implant. Fourteen young women preferred the implant’s location, mostly because of concerns that the IUD’s location would harm fertility, while seven young adults were more comfortable with the location of the IUD, mostly due to concerns that the implant’s location would reduce efficacy.

I don’t know if it’s a biased observation of me because I just feel like putting something in your vagina is just weird. I felt like that would just affect children but then maybe under the skin wouldn’t be as damaging maybe [client IDI39, teen, lower LARC provision site]

I think I would rather go for the IUD if I had to choose between the two. […] But it sounds kind of weird being under the skin of your arm [...] Just, you think, your uterus, that’s going to prevent pregnancy because it’s close to down there. The arm is far away [client IDI41, young adult, lower LARC provision site].

Directors and staff: Identifying and addressing challenges to providing LARCs to young women

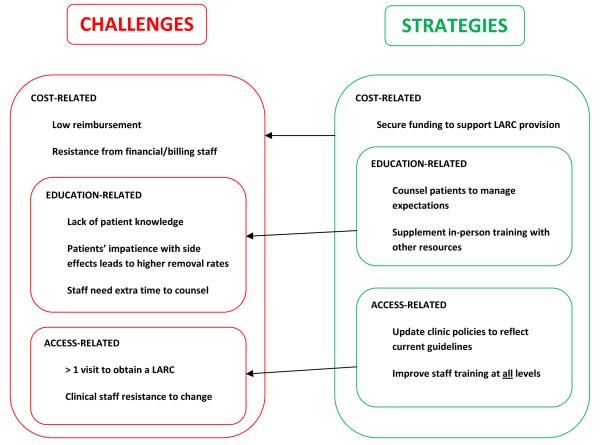

The director interviews and focus group discussions asked providers to identify challenges to providing LARCs to young women and to describe strategies their clinics use to address these challenges (Figure 2). All directors from sites with lower levels of LARC provision and most from higher-provision sites identified challenges to providing LARC methods to younger patients, and almost all of the identified challenges related to cost issues. Only directors from higher LARC provision sites named successful strategies. Several of the strategies outlined by providers addressed multiple challenges, sometimes at both the provider and patient levels.

Figure 2.

Challenges to providing LARCs to young women and strategies to combat these challenges, as identified by administrators and staff at lower rates of LARC provision facilities (challenges) and higher rates of LARC provision facilities (both challenges and strategies).

Addressing cost-related challenges

Several of the challenges, including time pressures and financial/billing staff resistance, directly relate to the higher costs incurred in time and money in providing LARC methods to young women. Cost-related challenges were mentioned more frequently by directors from sites with lower levels of LARC provision than from higher-provision sites. The low reimbursement from both public and private insurers for these methods was seen as a challenge, as clinics had to absorb some of the costs associated with providing them to patients. Some staff felt that money and time were “wasted” when providing LARC methods to young women, whom they perceived to be more likely to give up and have the methods removed when they became impatient with side effects.

So, when I, in this critical time of budget slashing and grants not being funded, if you ask me running this program, I love Depo. We were paying a quarter, a quarter, a vial two years ago for Depo. Now it is up to $2.10. It is still a deal...So that’s my argument on the other side: the IUD costs me a lot more money. If she takes it out in three months, I’m crying. Even if the insurance company is paying for it that is a waste of a lot of money and provider time [director interview 4, higher LARC provision site].

One director from a lower LARC provision site indicated that she felt that patients who paid for methods were more invested in them and were more willing to work through their side effects: “So I would say I see […] higher removal rates around people who don’t pay.” Staff in three FGDs described how frustrating it can be for providers when they feel that their resources are not being used properly.

…there is a lot of paperwork and follow up [for IUDs], not to mention we are tying up a clinician’s appointment time with people that I am not sure whether they are going to even follow up and do it and then are they going to keep it [staff FGD 5, lower LARC provision site].

Outside funding, including Title X and other grants as well as state Medicaid funds, helped sites to address the high costs directly associated with providing LARC methods. This funding also helped providers to incorporate some of the aforementioned strategies that were less directly related to cost issues, such as improved counseling and updated clinic policies. Several directors and staff at higher LARC provision sites described how the funds enabled them to offer the methods to clients for free or at a discount, and two directors indicated that, in the absence of these funding sources, costs would definitely pose a challenge to provision.

R: “…with the grant that we have got and being able to offer [LARC] completely free, I mean that is just a God-send. I mean otherwise I would say honestly, I mean if we didn’t have that, yeah, the challenge would be the cost, the cost of the actual device.”

I: “The cost of the device on the clinic side not on the patient side?”

R: “Well, both; it would be both, because we would have to pass the cost on to the patient, I mean we wouldn’t be able to give it to them free, if we didn’t have the grant funding that we have available. So, yeah, those long-term methods probably would not be as much of an option if the patients had to actually pay for themselves.” [director interview 13, higher LARC provision site]

Improving and supplementing counseling to reduce time constraints

Four directors indicated that, compared to pills, providing IUDs and implants to younger clients necessitated additional clinic time, as younger women typically had less knowledge about both their bodies and contraception than older women. Five directors described site-specific policies that required more extensive counseling for teens and young adults around LARCs than was required for older patients. These time constraints presented difficulties for clinic flow:

P1: The problem is going to be when we don’t have the time and they want us to see more patients per hour.

P2: That’s actually an incredibly important point that nobody has brought up before… counseling a young person takes longer than counseling an older person [staff FGD 6, higher LARC provision site].

Yet providing supportive, clear, and upfront counseling to help manage patients’ expectations of method side effects was seen as a key strategy for providing these methods to young women and reducing early removal rates, especially at higher provision sites.

We are really direct in the beginning in terms of saying, “Hey, we love these methods, they were extremely effective, here’s what you can expect, you are going to have a change of bleeding, you are going to bleed, you could bleed every single day”, just really, not sugarcoating it in any way, so that there is [not] false expectations of what to expect from the device. So a lot of counseling upfront [director interview 11, higher LARC provision site].

To combat some of the time pressures described above, several facilities supplemented their education with other sources of information on IUDs and implants, including educational pamphlets, videos shown to clients in the waiting room, and referrals to reputable websites.

Incorporating revised guidelines into clinic policies

Directors cited several sources of clinical guidance on LARC methods for young women, including ACOG (7), Title X (3), Contraceptive Technology (3), World Health Organization (2), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2). However, staff at three sites described challenges faced by their clients due to outdated facility policies regarding multiple appointments to obtain an IUD or implant, including counseling and insertion appointments at separate sites and requisite consultations for Pap, STI, and/or pregnancy tests before returning to get the methods (mostly IUDs) inserted. Still, some staff were apprehensive about eliminating the pelvic exam requirement for procurement of a contraceptive method with regard to clients who had never experienced a pelvic exam selecting an IUD.

I get a little concerned that the very first contraceptive method [IUD] that they use is something that causes pain and a period of adjustment. Where I get worried that I’ll taint them [against future pelvic exams]…And we do that a lot. First pelvic [exam] is an IUD insertion. [staff FGD 2, higher LARC provision site].

In contrast to patterns described at the lower LARC provision sites, three directors at higher provision sites described clinic policies regarding LARCs for teens and young adults that stressed the importance of avoiding unnecessary delays.

I think there [are] more recent studies saying that you don’t have to have advanced testing for IUDs, so we really try, if at all possible, on that first visit to get the woman, the method that she wants… So the fact, that people used to have to come in for [a] counseling visit, get a gonorrhea and chlamydia test that was negative before you had your IUD, really isn’t necessary anymore in that, if the risk factor is low and you screened out recent PID or known infection -- and obviously pregnancy -- then there is no reason you can’t get that young woman an IUD or an Implanon on that day [director interview 11, higher LARC provision site].

In one of the FGDs at a high-provision site, staff countered the perception of burdensome multiple visits by highlighting some benefits afforded by the additional time, namely the ability to confirm insurance and funding details and more time to decide on a method.

Improving provider buy-in to address staff resistance

Directors from sites with both higher and lower LARC provision depicted staff-related challenges, including resistance to change, lack of experience with the methods, and, as corroborated by some staff in the FGDs, attitudes about young women using IUDs and implants. Two directors identified resistance from administrative staff, who sometimes felt that the costs of providing IUDs and implants to younger clients outweighed their benefits, as a challenge.

We are only breaking even on the IUDs, and so now, well this is not really a primary concern for us in the clinic. It’s a big concern for the finance department and for my boss and her boss…they don’t see it as financially feasible for us to do it…I have providers yelling about how you know we need to do this, we need to do this and have these IUDs, and then my bosses are like don’t push that too much, don’t promote that too much [director interview 6, lower LARC provision site].

Directors from sites with both higher and lower LARC provision described encouraging staff to become personally invested in ensuring young women’s access to LARC methods as one strategy for combating staff resistance. Developing positive staff attitudes towards LARC often occurred within the context of staff trainings on LARC methods, which came from a variety of sources, with more directors from higher-provision than lower-provision sites (four vs. one) identifying external training sources such as conferences and state health department trainings, and more directors from lower-provision than higher-provision sites reporting internal sources of training, such as shadowing and in-house observations (three vs. six). Ensuring that all levels of staff, including clinicians, educators, receptionists, administrators and billing staff, were included in trainings about LARC methods and understood the benefits of LARC methods for young, sexually active women was cited by six directors from higher-provision sites but only one from a lower-provision site as a strategy for combating staff resistance. Directors at sites with lower levels of LARC provision more commonly talked about trainings that primarily focused only on clinical staff.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that, although some similarities in attitudes toward LARC methods for young women exist between clients and staff, these two groups prioritize certain advantages and disadvantages of the IUD and implant differently, which influences their opinions regarding the appropriateness of LARC methods for young women. Clients and staff agreed that the long-acting and easy to forget nature of IUDs and implants is well-suited to young women’s busy lifestyles and heightened desires to avoid pregnancy; however, some clients revealed contradictory attitudes about age as an eligibility criterion for LARC methods, describing IUDs and implants as more “serious” and appropriate for older women who wanted to limit their family size. This finding contrasts with findings from a recent qualitative study of young pill users who perceived friends who used longer-acting, non-daily methods to be more irresponsible for not being able to take a daily pill.33 Staff, on the other hand, did not see age as a limitation in and of itself, citing instead behavioral barriers, such as having multiple partners, and anatomical barriers associated with nulliparity, such as having a smaller cervix, as age-related reasons for young women’s possible LARC ineligibility.

Several clients were concerned that IUDs and implants were too long-lasting, suggesting a key educational and counseling message is that these methods are reversible and can be removed prior to their full duration, making them less “serious” and more appropriate to delaying initial childbearing. However, this message may not gain support from all staff, many of whom were discouraged by perceived high discontinuation rates among younger women and therefore steered these clients away from LARC methods. Yet many women discontinue other hormonal contraceptive methods for reasons similar to those cited for LARC methods, most commonly side effects,34 and an analysis of discontinuation at the national level indicates that young women are not more likely than older women to discontinue IUDs and implants due to dissatisfaction (M. Kavanaugh, unpublished data, June 2012). Ensuring that younger clients, who may be more “impatient” with side effects than older women, fully understand the potential side effects and benefits associated with IUDs and implants by encouraging staff to adopt a “managing expectations” style of counseling may be one avenue for addressing staff’s frustration with perceived high levels of discontinuation of LARCs among younger women.

Efficacy of LARC methods resonated with clients to a much greater extent than with staff, who were more focused on clinic-related concerns (e.g. cost issues and time constraints). Reorienting clinic-based discussions of contraceptive methods towards a tiered counseling approach based on method efficacy may better reflect clients’ perspectives. Among all clients, teens saw fewer advantages to using LARCs than young adults. Echoing sentiments expressed by young pill users,33 a few clients were also hesitant to trust LARC methods because of their perceived novelty and perceived lack of an established safety profile. Differing perspectives between providers and patients likely reflect differences between the groups in exposure to, and experiences with, young women using IUDs and implants; staff highlighted pros and cons that they had witnessed across their young patients in addition to logistical and financial issues related to providing LARCs at the clinic level, while clients, especially teens, more commonly responded to the idea of using a LARC method based on key information about IUDs and implants that was often newly introduced to them.

Although both groups slightly favored the implant over the IUD for young women, a more resonant finding across both staff and clients was that what one person perceives as a method advantage another might see as a disadvantage, and vice versa. These diverse attitudes represent differing needs among young women and emphasize the importance of the availability of a diverse method mix. In addition, they highlight the need for staff to employ an open-ended counseling style that does not make assumptions about what a client will find desirable, or off-putting, about any given method.

Several staff concerns regarding IUD and implant use among younger women, especially negative side effects and reduced use of condoms, are concerns that are applicable to most other short-term hormonal contraceptive methods.34 In addition, these concerns were not as salient to young women themselves. It isn’t clear why staff seemed more concerned about these potential disadvantages in relation to LARC methods, but it may be that they are more comfortable educating clients about the more familiar methods that are traditionally marketed to younger women. Emphasizing the importance of clients’ beliefs and desires regarding contraceptive methods in trainings on LARCs for staff at all levels would help them to better meet the contraceptive needs of their younger clients.

Strategies for combating facility-level challenges to providing LARC methods to young clients – including improved counseling for clients, broader training for staff, and updated, evidence-based facility guidelines – were all contingent on having financial support for these activities, as all required significant time and effort from staff. Implementation of the Affordable Care Act may enable more facilities to stock and provide IUDs and implants to young clients. The health reform law is expected to greatly expand the number of Americans with health insurance and will require most private insurance plans to cover the full range of women’s contraceptive methods without any co-payments or other out-of-pocket costs. Conferring longer term protection against unintended pregnancy without the need for frequent visits to a health care provider is an especially important strategy, given the changing guidelines regarding less frequent Pap tests35 and declining use of reproductive health services among young women in the US.36

Strengths of our study include the presence of both client and staff perspectives and the ability to draw comparisons between both IUDs and implants and teens and young adults. In addition, we focused our attention on staff and clients at publicly funded sites that provide family planning services because these sites serve clients at highest risk for unintended pregnancy, specifically low income, young, and minority women. However, our study is not without limitations. The qualitative nature of our study design allowed us to develop a deeper understanding of issues and concerns related to young women using LARC methods, yet it prevents us from generalizing our findings to all U.S. publicly funded family planning facilities or clients served at these sites. In addition, because we asked about the IUD before asking about the implant among both staff and clients, we were better able to identify more concrete attitudes and concerns specific to the IUD, while beliefs and feelings about the implant were often expressed as relative to the IUD. Use of IUDs and implants among clients in our sample was more common than use of these methods among teens and young adults nationally.9

Many providers, policy makers, program planners, and researchers focused on family planning have recognized the potential that LARC methods have to help young women avoid undesired pregnancies. Young women themselves are farther behind in widespread recognition of this potential,37 but our findings indicate that many do see IUDs and implants as feasible options for their lifestyle. Furthermore, data on LARC use at the national level indicate that young women are increasingly adopting these long-acting methods.9 However, given the limited knowledge and misconceptions about LARC methods among a substantial number of young women in our study, programs to educate young women about IUDs and implants through youth-friendly approaches are recommended. Since cost factors largely in whether facilities are able to provide LARC methods to young women, efforts to increase funding and support for these services are warranted. Attempts to increase provider-level awareness through updated guidelines and improved provider and staff trainings38 are currently underway but our findings suggest that fine-tuning messages about LARC methods to more accurately reflect clients’ concerns is justified. In addition, educational efforts targeting providers should emphasize available evidence regarding LARC trends and younger women’s needs in order to combat negative attitudes towards young women using IUDs and implants that are based on anecdotal, sometimes inaccurate, data at the facility level. Employing these strategies will help facilities move toward having a more comprehensive package of contraceptive services available to young women, fully integrating IUDs and implants into the arsenal of methods offered, and ultimately helping young women to avoid unintended pregnancy and better meet their reproductive goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amelia Bucek, Carolyn Cox, and Jesse Philbin for research support and Lawrence Finer, Jennifer Frost, Rachel Benson Gold, and Julie Edelson for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding source: The research on which this report was based was funded through a cooperative agreement between the Office of Population Affairs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Guttmacher Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health. 2006;38(2):90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Unintended Pregnancy . The best intentions: Unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Insitutue of Medicine; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finer LB. Unintended pregnancy among U.S. adolescents: Accounting for sexual activity. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010 Sep;47(3):312–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost JJ, Darroch JE, Remez L. Improving contraceptive use in the United States. Guttmacher Institute; New York: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1434–1438. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speidel JJ, Harper CC, Shields WC. The potential of long-acting reversible contraception to decrease unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2008 Sep;78(3):197–200. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Stewart F, et al., editors. Contraceptive Technology. 18th Revised ed Ardent Media, Inc.; New York: 2004. pp. 773–791. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraceptions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(21):1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007-2009. Fertil. Steril. 2012 Jul 13; doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaye K, Suellentrop K, Sloup C. The fog zone: How misperceptions, magical thinking, and ambivalence put young adults at risk for unplanned pregnancy. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster DG, Biggs MA, Ralph LJ, Arons A, Brindis CD. Family planning and life planning reproductive intentions among individuals seeking reproductive health care. Womens Health Issues. 2008 Sep-Oct;18(5):351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. Vital Health Stat. 2010;23(29) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Committee Opinion No. 392: Intrauterine device and adolescents. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1493–1495. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291575.93944.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraceptives: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227f05e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. medical eligbility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2010;59:1–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper CC, Blum M, Theil de Bocanegra H, et al. Challenges in translating evidence to practice: The provision of intrauterine contraception. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1359–1369. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318173fd83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: A survey of obstetrician and gynecologists’ knowledge and attitudes. Contraception. 2010 Feb;81(2):112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyler CP, Whiteman MK, Zapata LB, Curtis KM, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA. Health care provider attitudes and practices related to intrauterine devices for nulliparous women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012 Apr;119(4):762–771. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824aca39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo JA, Creinin MD. Update: Contraception. OBG Management. 2010;22(8):16, 18–20, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming KL, Sokoloff A, Raine TR. Attitudes and beliefs about the intrauterine device among teenagers and young women. Contraception. 2010 Aug;82(2):178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose SB, Cooper AJ, Baker NK, Lawton B. Attitudes toward long-acting reversible contraception among young women seeking abortion. J. Womens Health. 2011 Nov;20(11):1729–1735. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spies EL, Askelson NM, Gelman E, Losch M. Young women’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to long-acting reversible contraceptives. Womens Health Issues. 2010 Nov-Dec;20(6):394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanwood NL, Bradley KA. Young pregnant women’s knowledge of modern intrauterine devices. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;108(6):1417–1422. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245447.56585.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker AK, Johnson LM, Harwood B, Chiappetta L, Creinin MD, Gold MA. Adolescent and young adult women’s knowledge of and attitudes toward the intrauterine device. Contraception. 2008 Sep;78(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.04.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost JJ. Paper presented at: Research Conference on the National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: Oct 19, 2006. Using the NSFG to examine the scope and source of contraceptive and preventive reproductive health services obrained by U.S. women, 1995-2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Zapata LB, Ethier K, Moskosky S. Meeting the contraceptive needs of adolescents and young adults: Youth-friendly and long-acting reversible contraceptive services in U.S. family planning facilities. J. Adolesc. Health. forthcoming. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among the five approaches. 2nd ed Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. 2nd ed Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren CAB, Karner TX. Discovering qualitative methods: Field research, interviews, and analysis. 2nd ed Oxford University Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles M, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moustakas C. Phenomenological research methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carey MA. Comment: Concerns in the analysis of focus group data. Qual. Health Res. 1995;5(4):487–495. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundstrom B. Fifty years on “the pill”: a qualitative analysis of nondaily contraceptive options. Contraception. 2012 Jul;86(1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaughan B, Trussell J, Kost K, Singh S, Jones R. Discontinuation and resumption of contraceptive use: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2008 Oct;78(4):271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG practice bulletin 109: Cervical cytology screening. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1409–1420. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f8a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J. Determinants of and disparities in reproductive health service use among adolescent and young adult women in the United States, 2002-2008. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102(2):359–367. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mestad R, Secura G, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Acceptance of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods by adolescent participants in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception. 2011 Nov;84(5):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical Training Center for Family Planning [Accessed August 4, 2012];CTCFP/Title X Initiative: LARC-Reliable and Reversible Contraception of Choice 2012. http://www.larc.ctcfp.org/