Abstract

The present studies examined viability and DNA damage levels in mammary carcinoma cells following PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitor drug combination exposure. PARP1 inhibitors [AZD2281 ; ABT888 ; NU1025 ; AG014699] interacted with CHK1 inhibitors [UCN-01 ; AZD7762 ; LY2603618] to kill mammary carcinoma cells. PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors interacted to increase both single strand and double strand DNA breaks that correlated with increased γH2AX phosphorylation. Treatment of cells with CHK1 inhibitors increased the phosphorylation of CHK1 and ERK1/2. Knock down of ATM suppressed the drug-induced increases in CHK1 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation and enhanced tumor cell killing by PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors. Expression of dominant negative MEK1 enhanced drug-induced DNA damage whereas expression of activated MEK1 suppressed both the DNA damage response and tumor cell killing. Collectively our data demonstrate that PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors interact to kill mammary carcinoma cells and that increased DNA damage is a surrogate marker for the response of cells to this drug combination.

Keywords: PARP1, CHK1, DNA damage, ATM, kinase, apoptosis, comet

Introduction

Damage to DNA prompts signaling pathway activations that result in growth arrest / checkpoint responses. By preventing cell cycle transitions after DNA damage cells have time to repair their DNA prior to any cell division process. Cell cycle checkpoints are regulated primarily through the ataxia telangiectasia (ATM) and Rad3-related and ataxia telangiectasia-related (ATR) proteins.1-3 Phosphorylation of CHK1, downstream of ATR, regulates its activity and subsequently the functions of CDC25 protein phosphatases. Phosphorylation of CDC25A and CDC25C by CHK1 leads to their inactivation / degradation and blocks them from dephosphorylating and activating cyclin dependent kinases.4

There are several CHK1 inhibitors being examined as anti-tumor agents, alone and in combination with modalities that induce DNA damage. Simplistically these CHK1 inhibitory drugs have been argued to promote the lethal effects of chemotherapies by causing inappropriate cell cycle progression in the presence of damaged DNA.5-7 We have previously demonstrated that the CHK1 inhibitor UCN-01 and, more recently, the CHK1 inhibitor AZD7762 activates the ERK1/2 pathway and that inhibition of the ERK1/2 pathway promotes apoptosis and suppresses the growth of tumors.8-13 We have repeated our assays using molecular tools to inhibit CHK1 or maintain activation of the ERK1/2 pathway. UCN-01 is an ATP site dependent CHK1 inhibitor, but not a CHK2 inhibitor, and also has inhibitory effects on other protein kinases including PKC isoforms and PDK-1. AZD7762 is also an ATP site dependent and an equi-potent inhibitor of CHK1 and CHK2, with a much higher level of specificity for checkpoint kinases over other kinases. LY2603618 is also an ATP site dependent potent CHK1 inhibitor. This approach of simultaneously inhibiting two linked survival signaling pathways has also been shown for the ERK1/2 and PI3K pathways in some systems.14

One key protein in the regulation of DNA repair is poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is essential for repairing DNA damage through the base excision repair pathway.15 PARP1 binds to damaged DNA where its catalytic activity is stimulated, which leads to the synthesis of branched, protein-conjugated poly (ADP-ribose) to itself and other proteins that regulate base excision repair.16,17 Multiple PARP1 inhibitors have been developed including GPI15427, AG014699, ABT-888, NU1025 and AZD2281.18 Inhibitors that inhibit PARP1 can synergize with conventional genotoxic chemotherapies, including topoisomerase I inhibitors, ionizing radiation and DNA alkylating agents.19-26

The present studies were designed to determine whether PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors interacted to cause DNA damage and whether signaling by the ERK1/2 pathway regulated this process. PARP1 inhibitors interacted with CHK1 inhibitors to kill mammary carcinoma cells. PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors interacted to increase both single strand and double strand DNA breaks that correlated with increased γH2AX phosphorylation. Expression of dominant negative MEK1 enhanced drug-induced DNA damage whereas expression of activated MEK1 suppressed both the DNA damage response and tumor cell killing.

Results

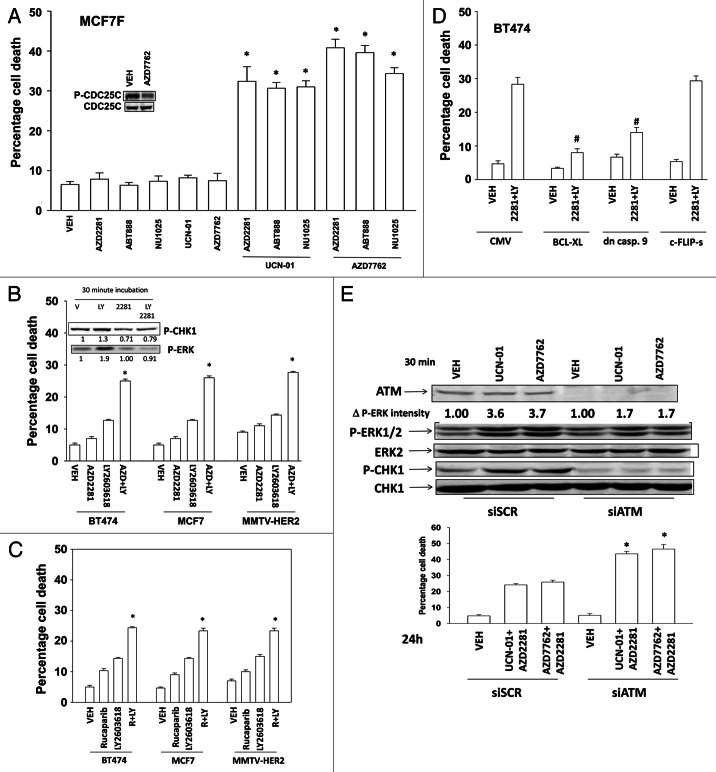

Exposure of fulvestrant resistant MCF7 cells to CHK1 inhibitors [UCN-01, AZD7762] and PARP1 inhibitors [AZD2281, ABT888, NU1025] resulted in a greater than additive increase in tumor cell death (Fig. 1A).28 Similar data were obtained in other breast cancer cell lines exposed to the CHK1 inhibitor LY2603618 and to the PARP inhibitors AZD2281 and AG014699 (Figs. 1B and C).29 Inhibition of the intrinsic, but not the extrinsic, apoptosis pathway blocked drug lethality (Fig. 1D). Treatment of cells with UCN-01 or AZD7762 increased ERK1/2 and CHK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1E). Knock down of ATM abolished drug-induced CHK1 phosphorylation and significantly reduced ERK1/2 activation. Knock down of ATM enhanced the lethality of the PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitor combination.

Figure 1. PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors interact to kill breast cancer cells. (A) Fulvestrant resistant MCF7F cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM), ABT888 (1 μM), NU1025 (10 μM), UCN-01 (50 nM) and AZD7762 (25 nM), and these agents in combination as presented in the panel. Cells were isolated 48h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 ± SEM) * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control. Inset blot: Cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or AZD7762 (25 nM); cells were isolated after 60 min and the phosphorylation of CDC25C determined. (B) BT474, MCF7 and MMTV-HER2 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM), LY2603618 (1 μM) or the drugs in combination. Cells were isolated 24h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 ± SEM) * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control. Inset blot: BT474 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM), LY2603618 (1 μM) or the drugs in combination. Cells were isolated 30 min after exposure and blotting performed to determine P-ERK and P-CHK1 levels. The fold change in P-ERK to total ERK and P-CHK1 to total CHK1 levels is presented. (C) BT474, MCF7 and MMTV-HER2 cells were treated with Rucaparib (1 μM), LY2603618 (1 μM) or the drugs in combination. Cells were isolated 24h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control. (D) BT474 cells were infected with an empty vector virus (CMV) or viruses to express BCL-XL, dominant negative caspase 9 or c-FLIP-s. Twenty four h after infection cells are treated with vehicle (DMSO) or AZD2281 (1 μM) and LY2603618 (1 μM). Cells were isolated 24h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 ± SEM). # p < 0.05 value less than corresponding virus control. (E) BT474 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (siSCR, 20 nM) or an siRNA to knock down ATM expression. Lower Graph: 24h after transfection cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or with [UCN-01, 50 nM + AZD2281, 1 μM] or [AZD7762, 25 nM + AZD2281 1 μM]. Cells were isolated 48h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 +/− SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding siSCR control. Upper blots: 24h after transfection cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or with [UCN-01, 50 nM] or [AZD7762, 25 nM]. Cells were isolated 30 min after exposure and blotting performed to determine P-ERK and P-CHK1 levels.

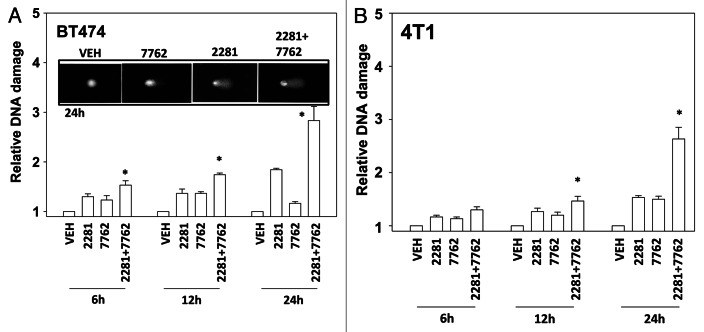

As CHK1 inhibitors were causing an apparent ATM/ATR activation in breast cancer cells and activation of these proteins is regulated by DNA damage, we next determined whether CHK1 and PARP inhibitors as single agents or in combination caused single strand and double strand DNA damage. Both CHK1 inhibitors and PARP1 inhibitors caused measurable single strand breaks (Figs. 2A and B). DNA damage caused by the drug combination appeared to be at least additive over the 24h time course.

Figure 2. CHK1 and PARP1 inhibitors interact to cause DNA damage. (A) BT474, (B) 4T1 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM), AZD7762 (25 nM) or the drug combination for the indicated times. Cells were isolated and subjected to alkaline comet assay. The length of the tail being scored 1–5 (n = 3 ± SEM) * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control.

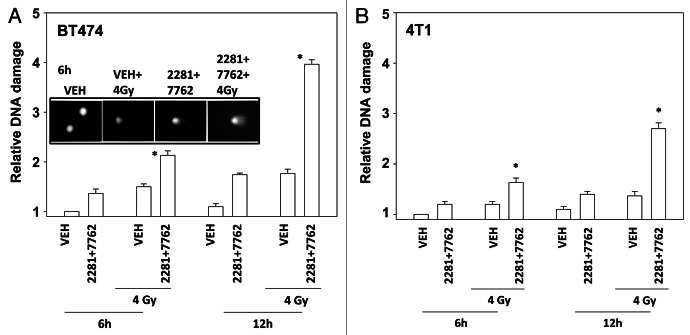

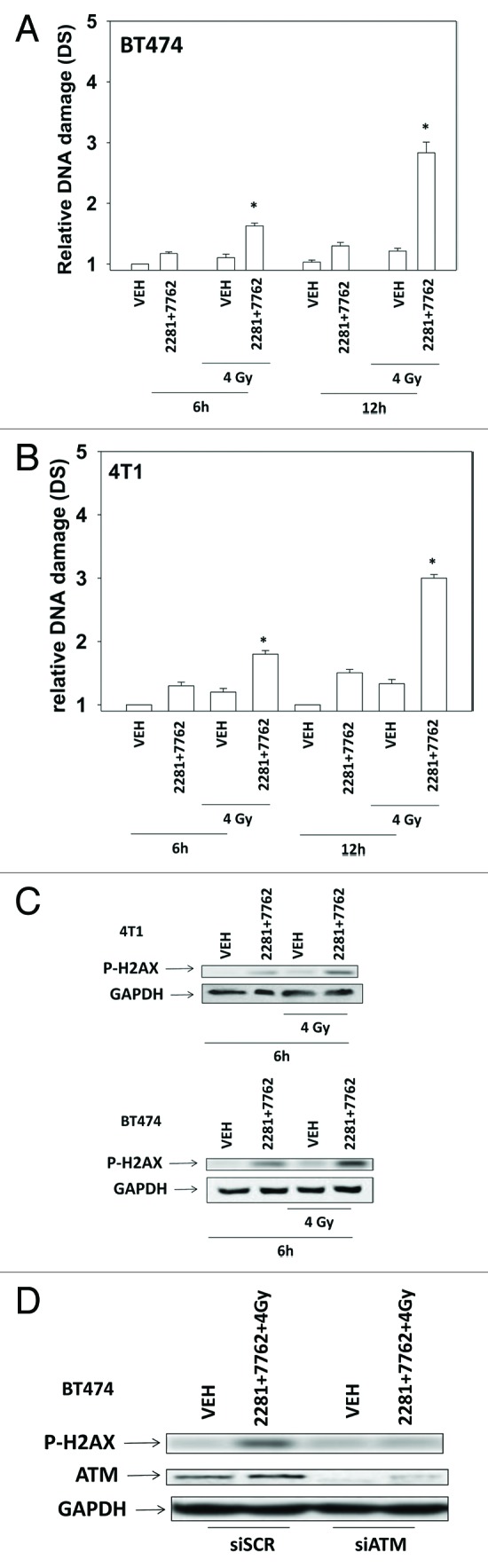

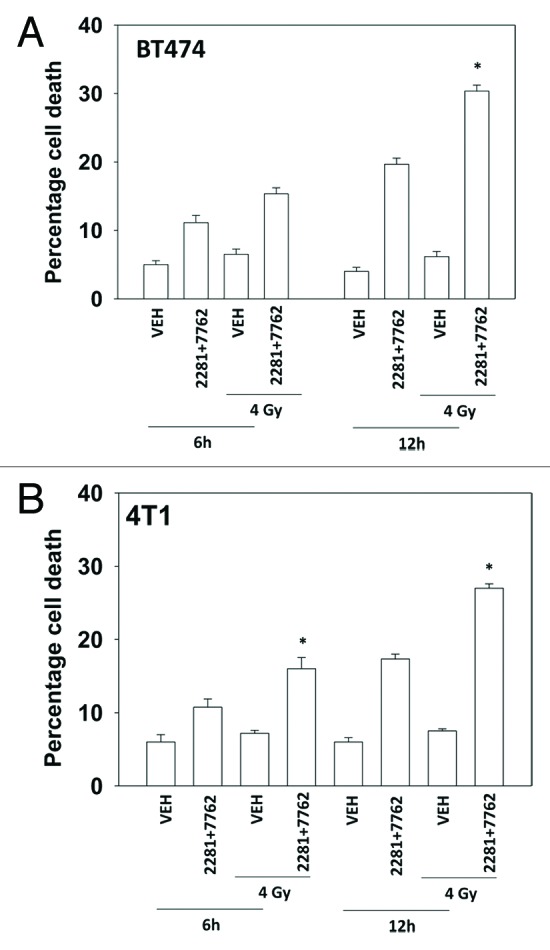

Treatment of cells with [PARP and CHK1 inhibitor] significantly enhanced the induction of single strand DNA damage after exposure to ionizing radiation (Figs. 3A and B). Similar data were obtained examining double strand DNA breaks (Figs. 4A and B). Treatment of cells with either PARP and CHK1 inhibitor or with radiation increased the phosphorylation of γH2AX (Fig. 4C). Knock down of ATM abolished the increase in γH2AX levels (Fig. 4D). Radiation and [PARP and CHK1 inhibitor] exposure interacted to radiosensitize breast cancer cells (Figs. 5A and B).

Figure 3. CHK1 and PARP1 inhibitors and ionizing radiation interact to cause DNA damage. (A) BT474, (B) 4T1 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for the indicated times. Cells were irradiated (4 Gy) 30 min after drug exposure. Cells were isolated and subjected to alkaline comet assay. The length of the tail being scored 1–5 (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control.

Figure 4. CHK1 and PARP1 inhibitors interact to cause double stranded DNA damage. (A) BT474, (B) 4T1 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for the indicated times. Cells were irradiated (4 Gy) 30 min after drug exposure. Cells were isolated and subjected to neutral comet assay. The length of the tail being scored 1–5 (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control. (C) BT474 and 4T1 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for 6h. As indicated cells were irradiated (4 Gy) 30 min after drug exposure. Blotting was performed to determine P-H2AX levels. (D) BT474 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (siSCR, 20 nM) or an siRNA to knock down ATM expression. Twenty four h after transfection cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for 6h. As indicated cells were irradiated (4 Gy) 30 min after drug exposure. Blotting was performed to determine P-H2AX levels.

Figure 5. PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors radiosensitize mammary carcinoma cells. (A) BT474, (B) 4T1 cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for 6h. As indicated cells were irradiated (4 Gy) 30 min after drug exposure. Cells were isolated 6h and 12h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control.

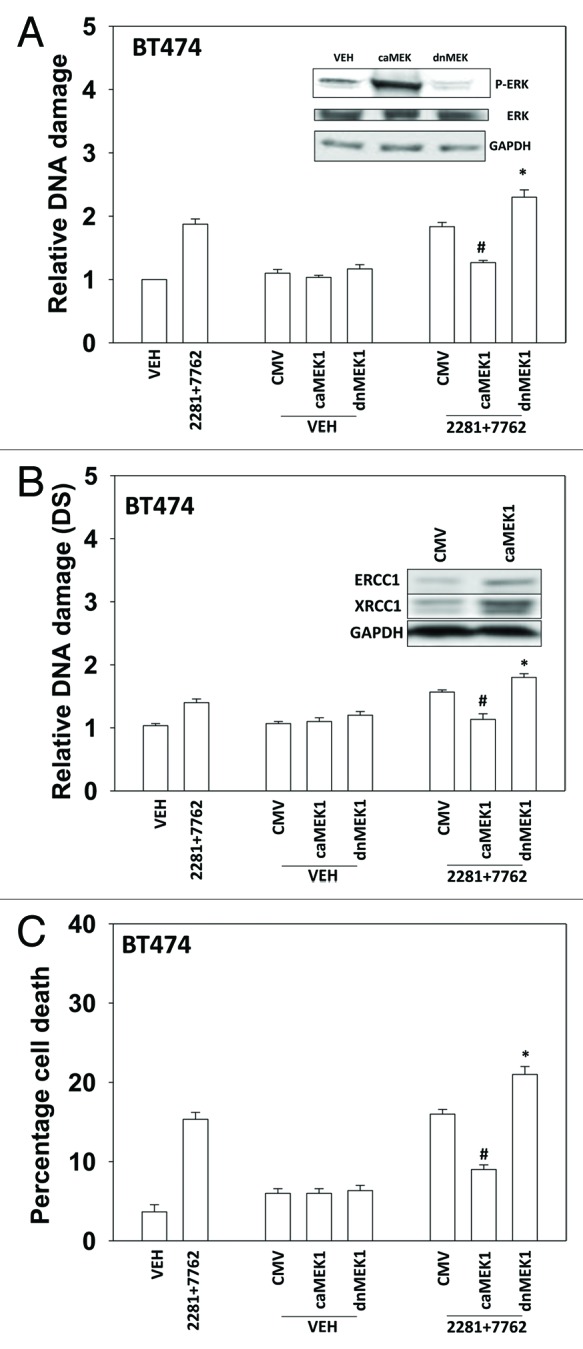

Based on the data in Figure 1, as well as our prior findings, were next examined whether alterations in ERK1/2 signaling regulated drug-induced DNA damage and cell viability. Expression of dominant negative MEK1 reduced basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation and enhanced drug-induced DNA damage (Figs. 6A and B). Expression of activated MEK1 enhanced basal ERK1/2 phosphorylation and suppressed drug-induced DNA damage. Expression of dominant negative MEK1 enhanced drug-induced cell killing and expression of activated MEK1 suppressed drug lethality (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. MER-ERK signaling regulates the DNA damage response following PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitor treatment. (A) BT474 cells were infected with empty vector adenovirus (CMV) or viruses to express dominant negative MEK1 (dnMEK1) or activated MEK1 (caMEK1). Twenty four h after infection cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for 24h. Cells were isolated and subjected to alkaline comet assay. The length of the tail being scored 1–5 (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control; # p < 0.05 value less than corresponding vehicle control. Inset blot: the levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in cells expressing caMEK1 and dnMEK1. (B) BT474 cells were infected with empty vector adenovirus (CMV) or viruses to express dominant negative MEK1 (dnMEK1) or activated MEK1 (caMEK1). Twenty four h after infection cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination for 24h. Cells were isolated and subjected to neutral comet assay. The length of the tail being scored 1–5 (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control; # p < 0.05 value less than corresponding vehicle control. Inset blot: the levels of ERCC1 and XRCC1 in cells expressing caMEK1. (C) BT474 cells were infected with empty vector adenovirus (CMV) or viruses to express dominant negative MEK1 (dnMEK1) or activated MEK1 (caMEK1). Twenty four h after infection cells were treated with AZD2281 (1 μM) and AZD7762 (25 nM) in combination. Cells were isolated 24h after exposure, and viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. (n = 3 ± SEM). * p < 0.05 value greater than corresponding vehicle control; # p < 0.05 value less than corresponding vehicle control.

Discussion

Prior studies have shown that inhibitors of MEK1/2 as well as inhibitors of PARP1 interact with CHK1 inhibitors to kill tumor cells.12,13,30 The present studies were performed to determine in further detail the biology by which PARP1 inhibitors interact with CHK1 inhibitors to promote breast cancer cell killing. Multiple PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors interacted in a greater than additive fashion to kill mammary tumor cells. Inhibition of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, but not the extrinsic pathway, blocked tumor cell killing.

The present studies used three CHK1 inhibitors and four PARP1 inhibitors. All three of the CHK1 inhibitors have undergone Phase I clinical testing with LY2603618 about to move into Phase III trials. The development of UCN-01 has been hampered by poor PK/PD issues and AZD7762 in Phase I trials was shown to have cardiac toxicity.30-32 PARP1 inhibitors have undergone Phase III trials however in breast cancer patients they unexpectedly did not show a significant clinical benefit to patients.33,34 PARP1 inhibitor trials in other malignancies are still on-going.35,36

CHK and PARP inhibitors interacted to cause single strand and double strand DNA breaks. PARP is known to regulate base excision repair whereas CHK signaling plays a role in regulating the G1 and G2 checkpoints as well as homologous recombination repair.37-39 Prior studies have shown that the interaction of CHK1 inhibitors with MEK1/2 inhibitors does not require cells to be proliferating but does require cell transformation. Thus our data with CHK and PARP inhibitors argues that the DNA damage responses we are observing are likely not due to proliferation effects.

Radiotherapy is frequently used to treat breast cancer patients. Our data demonstrated that [CHK and PARP] inhibitor treatment radiosensitized breast cancer cells. This correlated with a large enhancement in the levels of single strand and double strand breaks in drug treated cells exposed to radiation (and to PARP1 and CHK1 inhibitors). Of note was the fact that the levels of radiation-induced single and double strand breaks were much lower than that induced by the drug combination plus irradiation at the time points examined.

Expression of activated MEK1 suppressed DNA damage caused by the drug combination whereas expression of dominant negative MEK1 enhanced damage. Prior studies from our group have linked ERK1/2 pathway signaling to increased expression of ERCC1 and XRCC1.40 PARP and XRCC1 cooperate in base excision repair.17,39 Studies have also linked ATM activation to activation of the ERK1/2 pathway.41 Activated MEK1 increased the levels of both ERCC1 and XRCC1 in breast cancer cells arguing that a portion of the mechanism by which activated MEK1 could suppress DNA damage is through upregulation of these proteins.

Materials and Methods

Materials

BT474 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and were not further validated. Parental and fulvestrant-resistant MCF7 cells were a kind gift from Dr K. Nephew (University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from HyClone. Antibiotics-antimycotics (100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 250 μg/ml amphotericin B) and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All the primary antibodies used in the present study were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The validated siRNA molecules used to knock down ATM were from Qiagen: reference number GS472. siPORT NeoFX transfection agent was purchased from Ambion. Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent was purchased Invitrogen. The CHK1 inhibitor AZD7762 and the PARP1 inhibitors AZD2281 and ABT-888 were purchased from Axon Medchem.27 UCN-01 and NU-1025 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The CHK1 inhibitor LY2603618 was purchased from Selleckchem.12,13

Culture and in vitro exposure of cells to drugs

All breast cancer cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic in a humidified incubator under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. In vitro drug treatments were from 10 mM stock solutions of each drug, and the maximal concentration of vehicle (DMSO) in media was 0.02% (v/v).

Cell treatments, SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis

For in vitro analyses of short-term apoptosis effects, cells were treated with vehicle/drugs or their combination for the indicated times. Cells were isolated at the times indicated in the figures by trypsinization. Cell viability, which is based on the traditional cell viability method of trypan blue exclusion, was measured with Vi-CELL Series cell viability analyzers (Beckman Coulter).

For SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, cells were plated at 5 × 105 cells/cm and treated with therapeutic drugs at the indicated concentrations and after the indicated time of treatment and lysed with whole-cell lysis buffer (0.5 M TRIS-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol and 0.02% bromphenol blue) in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), and the samples were sonicated and boiled for 5 min. The boiled samples were loaded onto 10 to 14% SDS-PAGE and were fractionated by SDS-PAGE gels in a Protean II system (Bio-Rad). After proteins were transferred to the Immobilon-FL polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the membrane was blocked with Odyssey Blocking buffer from LI-COR Biosciences for 60 min at room temperature and incubated with the primary antibody at appropriate dilutions in Odyssey Blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. After overnight incubation with appropriate primary antibodies, the membrane was washed (three times) with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 for a total of 15 min, probed with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (1:5000) for 80 min at room temperature and washed (three times) with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 for a total of 15 min. The immunoblots were visualized by an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

siRNA and plasmid transfection in vitro

siRNA transfection was performed with siPORT NeoFX transfection agent following the manufacturer's procedures. In brief, 20 nM prevalidated siRNA was diluted into 50 μl of serum-free media. On the basis of the manufacturer's instructions, an appropriate amount of siPORT NeoFX transfection agent was diluted into a separate vial containing serum-free media. The two solutions were incubated separately at room temperature for 15 min and mixed together by pipetting up and down several times, and the mixture was added drop-wise to the target cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the transfection medium was replaced with complete medium, and 12 h later the cells were subjected to treatments. Procedures used for plasmid transfection were similar to those for siRNA, but instead Lipofectamine 2000 was used as the transfection reagent.

Alkaline and neutral single cell gel ectrophoresis assay

The comet assay was performed following Rojas et al. Essentially, 85 μl molten agarose in PBS was dropped on to a microscope slide pre-coated with 1% agarose, covered with a 18 × 18 mm No.1 glass coverslip and placed on ice to allow the agarose to set. The coverslip was then removed. Following appropriate treatment, 5 µl of the sample of cells (5 × 104 cells) was mixed with 85 μl of 1% low melting agarose and immediately pipetted onto the layer of 1% agarose on the microscope slide. The coverslip was replaced and the slide placed on ice to allow the agarose to set. The coverslip was then removed and the slide immersed in 150 ml of ice cold lysis buffer (2.5 M sodium chloride, 85 mM EDTA, 10 mM Trizma base and adjusted to pH 10 with sodium hydroxide pellets), containing 1% Triton-X 100 (v/v) and 10% DMSO (v/v). The cells were incubated in the lysis buffer at 4°C for 60 min. All steps following the lysis procedure were performed under dim light conditions. On removal from the lysis buffer, slides were incubated in the electrophoresis buffer (containing 0.3 M sodium hydroxide and 1 mM EDTA, for 20 min prior to electrophoresis at 20 V/32 mA for 24 min. The 20 min pre-incubation period prior to electrophoresis allows the alkaline pH of the electrophoresis buffer to destroy the remains of the chromatin structure and allow the DNA to “uncoil.” The neutral assay was performed essential as the alkakine assay except TRIS-acetate-EDTA buffer was used as the electrophoresis buffer. Subsequent electrophoresis then facilitates the migration of fragmented DNA. Following electrophoresis the slides were transferred to an absorbent surface and washed three times with neutralizing buffer, (100 mM Trizma base, pH 7.5). Remaining nucleoids and any extra-cellular DNA were stained using 10 μl of a 50 μg/ml stock solution of the fluorescent stain, ethidium bromide. A coverslip was immediately replaced and the slides were analyzed immediately or stored overnight in humidified atmosphere at 4°C.

The nucleiods were analyzed microscopically using a manual scoring system ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 representing undamaged cells and 5 representing severe damage as demonstrated by Collins AR. The comet assay for DNA damage and repair. Mol. Biotech. 26: 249–261. 100 cell/slide or experimental point was analyzed, with damage detection varying from 100 to 500. Experimental results were divided by vehicle control values in each experiment to produce relative values for comparison between individual experiments. Results plus the standard error of the mean are displayed here.

Data analysis

The effects of various in vitro drug treatments were compared by analysis of variance using Student's t-test. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Experiments shown are the means of multiple individual points from multiple studies (± S.E.M.). For statistical examination of in vivo animal survival data, log-rank statistical analyses between the different treatment groups were used. Experiments shown are the means of multiple individual points from multiple experiments (± S.E.M.).

Acknowledgments

Support for the present study was funded from PHS grants from the National Institutes of Health [R01-CA141704, R01-CA150214, R01-DK52825] and the Department of Defense [W81XWH-10–1-0009]. P.D. is the holder of the Universal Inc. Professorship in Signal Transduction Research.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- MEK

mitogen activated extracellular regulated kinase

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- PI3K

phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase

- −/−

null / gene deleted

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen activated extracellular regulated kinase

- JNK

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- dn

dominant negative

- P

phospho-

- ca

constitutively active

- WT

wild type

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/24424

References

- 1.Lukas C, Falck J, Bartkova J, Bartek J, Lukas J. Distinct spatiotemporal dynamics of mammalian checkpoint regulators induced by DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:255–60. doi: 10.1038/ncb945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Capetillo O, Lee A, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:959–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JH, Paull TT. Activation and regulation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Oncogene. 2007;26:7741–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–9. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Zhao L, Parsels JD, Davis MA, Hassan MC, et al. Mechanism of radiosensitization by the Chk1/2 inhibitor AZD7762 involves abrogation of the G2 checkpoint and inhibition of homologous recombinational DNA repair. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4972–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mow BM, Blajeski AL, Chandra J, Kaufmann SH. Apoptosis and the response to anticancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13:453–62. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prudhomme M. Novel checkpoint 1 inhibitors. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2006;1:55–68. doi: 10.2174/157489206775246520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai Y, Yu C, Singh V, Tang L, Wang Z, McInistry R, et al. Pharmacological inhibitors of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase/MAPK cascade interact synergistically with UCN-01 to induce mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5106–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai Y, Landowski TH, Rosen ST, Dent P, Grant S. Combined treatment with the checkpoint abrogator UCN-01 and MEK1/2 inhibitors potently induces apoptosis in drug-sensitive and -resistant myeloma cells through an IL-6-independent mechanism. Blood. 2002;100:3333–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai Y, Chen S, Pei XY, Almenara JA, Kramer LB, Venditti CA, et al. Interruption of the Ras/MEK/ERK signaling cascade enhances Chk1 inhibitor-induced DNA damage in vitro and in vivo in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2008;112:2439–49. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamed H, Hawkins W, Mitchell C, Gilfor D, Zhang G, Pei XY, et al. Transient exposure of carcinoma cells to RAS/MEK inhibitors and UCN-01 causes cell death in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:616–29. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell C, Park M, Eulitt P, Yang C, Yacoub A, Dent P. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 modulates the lethality of CHK1 inhibitors in carcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:909–17. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang Y, Hamed HA, Poklepovic A, Dai Y, Grant S, Dent P. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 modulates the lethality of CHK1 inhibitors in mammary tumors. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:322–32. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, Kaufmann SH, Poirier GG. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amé JC, Rolli V, Schreiber V, Niedergang C, Apiou F, Decker P, et al. PARP-2, A novel mammalian DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17860–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber V, Amé JC, Dollé P, Schultz I, Rinaldi B, Fraulob V, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 (PARP-2) is required for efficient base excision DNA repair in association with PARP-1 and XRCC1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23028–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graziani G, Szabó C. Clinical perspectives of PARP inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arundel-Suto CM, Scavone SV, Turner WR, Suto MJ, Sebolt-Leopold JS. Effect of PD 128763, a new potent inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, on X-ray-induced cellular recovery processes in Chinese hamster V79 cells. Radiat Res. 1991;126:367–71. doi: 10.2307/3577927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Hur E, Chen CC, Elkind MM. Inhibitors of poly(adenosine diphosphoribose) synthetase, examination of metabolic perturbations, and enhancement of radiation response in Chinese hamster cells. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2123–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulton S, Pemberton LC, Porteous JK, Curtin NJ, Griffin RJ, Golding BT, et al. Potentiation of temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity: a comparative study of the biological effects of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:849–56. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman KJ, Newell DR, Calvert AH, Curtin NJ. Differential effects of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor NU1025 on topoisomerase I and II inhibitor cytotoxicity in L1210 cells in vitro. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:106–12. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowman KJ, White A, Golding BT, Griffin RJ, Curtin NJ. Potentiation of anti-cancer agent cytotoxicity by the potent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors NU1025 and NU1064. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1269–77. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaney CA, Wang LZ, Kyle S, White AW, Calvert AH, Curtin NJ, et al. Potentiation of temozolomide and topotecan growth inhibition and cytotoxicity by novel poly(adenosine diphosphoribose) polymerase inhibitors in a panel of human tumor cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2860–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tentori L, Portarena I, Graziani G. Potential clinical applications of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2002;45:73–85. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodon J, Iniesta MD, Papadopoulos K. Development of PARP inhibitors in oncology. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:31–43. doi: 10.1517/13543780802525324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donawho CK, Luo Y, Luo Y, Penning TD, Bauch JL, Bouska JJ, et al. ABT-888, an orally active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that potentiates DNA-damaging agents in preclinical tumor models. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2728–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan M, Yan PS, Hartman-Frey C, Chen L, Paik H, Oyer SL, et al. Diverse gene expression and DNA methylation profiles correlate with differential adaptation of breast cancer cells to the antiestrogens tamoxifen and fulvestrant. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11954–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss GJ, Donehower RC, Iyengar T, Ramanathan RK, Lewandowski K, Westin E, et al. Phase I dose-escalation study to examine the safety and tolerability of LY2603618, a checkpoint 1 kinase inhibitor, administered 1 day after pemetrexed 500 mg/m(2) every 21 days in patients with cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2013;31:136–44. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dent P, Tang Y, Yacoub A, Dai Y, Fisher PB, Grant S. CHK1 inhibitors in combination chemotherapy: thinking beyond the cell cycle. Mol Interv. 2011;11:133–40. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.2.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sausville EA, LoRusso P, Carducci MA, Barker PN, Agbo F, Oakes P, Senderowicz AM. Phase I dose-escalation study of AZD7762 in combination with gemcitabine (gem) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29suppl [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tse AN, Carvajal R, Schwartz GK. Targeting checkpoint kinase 1 in cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1955–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guha M. PARP inhibitors stumble in breast cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:373–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt0511-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan OA, Gore M, Lorigan P, Stone J, Greystoke A, Burke W, et al. A phase I study of the safety and tolerability of olaparib (AZD2281, KU0059436) and dacarbazine in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:750–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riches LC, Lynch AM, Gooderham NJ. Early events in the mammalian response to DNA double-strand breaks. Mutagenesis. 2008;23:331–9. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gen039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Ann. rev. Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ström CE, Johansson F, Uhlén M, Szigyarto CA, Erixon K, Helleday T. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is not involved in base excision repair but PARP inhibition traps a single-strand intermediate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3166–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yacoub A, McKinstry R, Hinman D, Chung T, Dent P, Hagan MP. Epidermal growth factor and ionizing radiation up-regulate the DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC1 in DU145 and LNCaP prostate carcinoma through MAPK signaling. Radiat Res. 2003;159:439–52. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0439:EGFAIR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golding SE, Rosenberg E, Neill S, Dent P, Povirk LF, Valerie K. Extracellular signal-related kinase positively regulates ataxia telangiectasia mutated, homologous recombination repair, and the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1046–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]