Abstract

Although recent studies have established that osteocytes function as secretory cells that regulate phosphate metabolism, the biomolecular mechanism(s) underlying these effects remain incompletely defined. However, investigations focusing on the pathogenesis of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR), and autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR), heritable disorders characterized by abnormal renal phosphate wasting and bone mineralization, have clearly implicated FGF23 as a central factor in osteocytes underlying renal phosphate wasting, documented new molecular pathways regulating FGF23 production, and revealed complementary abnormalities in osteocytes that regulate bone mineralization. The seminal observations leading to these discoveries were the following: 1) mutations in FGF23 cause ADHR by limiting cleavage of the bioactive intact molecule, at a subtilisin-like protein convertase (SPC) site, resulting in increased circulating FGF23 levels and hypophosphatemia; 2) mutations in DMP1 cause ARHR, not only by increasing serum FGF23, albeit by enhanced production and not limited cleavage, but also by limiting production of the active DMP1 component, the C-terminal fragment, resulting in dysregulated production of DKK1 and β-catenin, which contributes to impaired bone mineralization; and 3) mutations in PHEX cause XLH both by altering FGF23 proteolysis and production and causing dysregulated production of DKK1 and β-catenin, similar to abnormalities in ADHR and ARHR, but secondary to different central pathophysiological events. These discoveries indicate that ADHR, XLH, and ARHR represent three related heritable hypophosphatemic diseases that arise from mutations in, or dysregulation of, a single common gene product, FGF23 and, in ARHR and XLH, complimentary DMP1 and PHEX directed events that contribute to abnormal bone mineralization.

Introduction

Osteocytes are cells embedded in the mineralized bone matrix, connected to each other and cells outside the bone through a bone fluid-filled lacunocanalicular system. Recently, a variety of studies have established that osteocytes function as secretory cells, which regulate phosphate and calcium metabolism, and as endocrine cells that send signals to distant organs, most notably the kidneys [1]. Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23), an important hormone regulating serum phosphate levels, is most highly expressed in bone, predominantly the osteocytes. While phosphate, calcium, and αKlotho protein are among the principal factors modulating FGF23 production and secretion by osteocytes, the biomolecular mechanism(s) underlying these effects remain incompletely defined.

The heritable disorders of renal phosphate transport, including X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR), and autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR), are the most common disturbances of phosphate homeostasis, characterized by renal phosphate wasting, hypophosphatemia, and abnormal bone mineralization. Until recently, the pathophysiological basis of these heritable disorders remained elusive, because the hormonal/metabolic control of renal phosphate reabsorption and bone mineralization was not completely understood. However, the observation that FGF23 dramatically increases in the osteocytes of animal models with ARHR, and XLH [2] suggests that an elevated serum FGF23 concentration is a common pathogenetic abnormality, underlying aberrant phosphate homeostasis and biomineralization in these diseases. Indeed, a significant series of investigations in affected patients with, and murine homologs of, these diseases have provided clear evidence that an increased circulating level of FGF23 is responsible for increased renal phosphate loss and hypophosphatemia, and contributes to impaired bone mineralization in these heritable disorders.

Over the past several years, the gene abnormalities underlying XLH (PHEX), ADHR (FGF23) and ARHR (DMP1) have been identified, and the colocalization of PHEX and DMP1 with FGF23 in osteocytes has been documented. Moreover, the integrated biomolecular mechanisms underlying the enhanced osteocyte FGF23 production/secretion in XLH, ADHR, and ARHR have become increasingly better defined (Table 1). These observations suggest that osteocyte regulation of phosphate homeostasis and bone mineralization results from the integrated effects of FGF23, PHEX, and DMP1. Studies supporting such integrated activities documented that FGF23 is not the sole regulator of bone mineralization in the hypophosphatemic rachitic/osteomalacic diseases. Thus, blocking the actions of FGF23, and correcting the hypophosphatemia, while healing the rachitic abnormalities of these diseases, only marginally reduces the severity of the characteristic osteomalacia. These data indicate that PHEX activity in XLH and DMP1 activity in ARHR contribute to regulation of bone mineralization. The fascination resulting from these observations is recognition of the regulatory role that osteocytes play in the management of not only bone mineralization, but also a primary renal function, phosphate reabsorption. Thus, the remainder of this paper focuses on the interrelated events that underlie the phenotype of these heritable hypophosphatemic disorders. As will become evident, the osteocytes manage a chain of secretory, hormonal and molecular mechanisms that, when deranged, results in a cascade of events that leads to the pathophysiological expression of XLH, ADHR, and ARHR.

Table 1.

Osteocyte regulation of FGF23.

| Disease | ADH | ARHR | XLH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal gene | FGF23 | DMP1 | PHEX |

| Transmission | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal recessive | X-linked dominant |

|

| |||

| FGF23 | |||

|

| |||

| Serum FGF23 | N* or ⇑ | N or ⇑ | N* or ⇑ |

|

| |||

| Production | N* or ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ |

|

| |||

| Degradation | ⇓ | N | ⇓ |

|

| |||

| Bioactivity | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ |

N*: Inappropriately normal for the prevailing serum P level.

Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets

Clinical presentation

Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR), initially described in 1971 by Bianchine et al. [3], is a rare disorder, characterized in full expression by: 1) hypophosphatemia, secondary to renal phosphate wasting; 2) an inappropriately low or normal serum calcitriol level, relative to the serum phosphorus concentration; and 3) rickets/osteomalacia. Unlike other hereditable forms of hypophosphatemic rickets, ADHR displays incomplete penetrance and variable age of onset [4]. Approximately 50% of affected patients have early onset of disease, presenting with renal phosphate wasting, lower extremity deformities, and dental abnormalities in childhood. In some of these subjects, hypophosphatemia and renal phosphate wasting persist into adulthood, while in others these abnormalities disappear. The remaining affected patients have late onset of clinically evident disease, presenting from puberty to over 50 years of age. Symptoms accompanying the late onset disease include classic biochemical abnormal lities, bone pain, weakness, and pseudofractures, a clinical profile similar to patients with tumor-induced osteomalacia, an acquired disorder often presenting late in life.

Genetic abnormality

Using large well-characterized ADHR kindreds, Econs et al. [5] employed positional cloning to map the ADHR disease locus, and a linkage region was identified on chromosome 12p13.3. FGF23 was tested as a candidate gene, and missense mutations within the full length molecule were identified in the ADHR families. To date, four different mutations have been documented, each affecting the arginines within R176XXR179/S180, a subtilisin-like proprotein (SPC) consensus cleavage site (R176Q, R176W, R179Q, and R179W) [6] and [7]. The cleavage site separates the N-terminal FGF-like domain from the C-terminal tail (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

FGF23 protein domains and the ADHR mutations. FGF23 has a 24-amino acid signal peptide, followed by amino acids 25–179 that comprise the N-terminal FGF-like domain. The ADHR mutations at R176 and R179 (R176Q/W; R179Q/W) occur within the FGF23 subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (SPC) site, separating the conserved FGF-like domain from the more variable C-terminal tail (amino acids 180–251). FGF23 is glycosylated within two larger regions (denoted as ‘{GLY}’). T178 is a key glycosylated residue that may protect the mature, intact hormone from SPC degradation.

The SPCs, including the protease furin, are a family of serine proteases expressed in the trans-Golgi network that possess similar, but not exact, substrate specificities and cleave polypeptides into N- and C-terminal fragments with the basic motif K/R-Xn-KR [8] and [9]. In ADHR, the FGF23 mutations cause partial resistance to proteolytic cleavage of intact FGF23, which is highly expressed in bone, predominantly in the osteocytes. The resultant limited FGF23 degradation increases the serum FGF23 (see below).

Molecular genetics and animal models

The seminal discovery that mutations in FGF23 cause ADHR provided the first link to understanding the interwoven pathogenesis of the genetic hypophosphatemic diseases and the pivotal role of the osteocytes in the genesis of these diseases. Central to this understanding was the documentation that FGF23 cleavage occurs at the RXXR motif, the site of the missense mutations in patients with ADHR (Fig. 1). Using immunoblot analysis with antibodies to the C-terminal portion of FGF23, Benet-Pages et al. [10] documented that two different species of FGF23, 32 kDa and 12 kDa, were secreted from cells expressing the wild type (WT) FGF23 cDNA. Peptide sequencing confirmed that the 32 kDa isoform corresponded to full length FGF23 (residues 25–251), after cleavage of the signal peptide, and that the 12 kDa isoform was the C-terminal portion of FGF23, immediately downstream from the SPC consensus cleavage site (residues 180–251). Additional evidence for the SPC dependent cleavage of FGF23 was obtained in experiments documenting that the intracellular cleavage of wild-type FGF23 is inhibited by a non-specific inhibitor, Dec-RVKR-CMK. Moreover, Yuan et al. [11] reported that FGF23 proteolysis in bone cells is achieved by SPC2 and its co-factor, 7B2. These observations confirmed that proteolytic cleavage of FGF23, in fact, occurs at the RXXR motif.

Subsequent studies documented that the ADHR mutations indeed limit cleavage of the intact protein. Site directed mutagenesis was employed to introduce the ADHR mutations into the FGF23 cleavage site at either R176 or R179. Secreted FGF23, containing the mutations, was primarily the full length 32 kDa form, indicating that the mutated FGF23, is clearly resistant to cleavage and undergoes only limited proteolytic processing [12] and [13]. These data, in concert with those documenting that FGF23 bioactivity is limited to the intact protein, are consistent with the supposition that ADHR mutations protect FGF23 from proteolysis, thereby elevating circulating concentrations of intact FGF23 and leading to renal phosphate wasting in affected patients. Thus, the pathophysiological basis for ADHR is seemingly a gain-of-function mutation that retains and increases the biological potency of the FGF23 protein.

Although these studies predict that the ADHR phenotype is caused by an elevated circulating concentration of cleavage-resistant FGF23, they provide no explanation for the variable penetrance of the disease. Interestingly, however, recent studies show that the serum FGF23 concentration is not consistently elevated in patients with the FGF23 mutations characteristic of ADHR. Rather the FGF23 concentration is elevated only when active disease is present [14]. Even patients in disease remission, despite having a prior history of clinical manifestations, have serum FGF23 levels within the normal range [14]. While the cause of the variably modulated serum FGF23 concentration in patients with ADHR is not immediately apparent, the delayed onset of the disease phenotype occurs primarily in females during puberty and following pregnancy. During active disease, reduced serum phosphate levels are correlated with elevated plasma FGF23, but with disease waning, reductions of circulating FGF23 coincide with normalization of serum phosphate and resolution of metabolic bone disease.

Both puberty and pregnancy are physiological situations prone to iron deficiency and recent studies indicate that C-terminal FGF23 is negatively correlated with ferritin concentrations [15]. With these findings in mind, the hypothesis was tested that an ADHR disease phenotype could be induced by decreasing the iron load. Mice carrying a knock-in ADHR mutation (R176Q) and WT mice were placed on control and low iron diets. This treatment regimen resulted in similar iron deficient anemia in the WT and ADHR mice. However, while the ADHR mice demonstrated significant hypophosphatemia, normocalcemia and elevated alkaline phosphatase, the iron deficient WT mice maintained normal phosphate metabolism [16].

Molecular analyses of the skeleton showed that iron deficiency in the ADHR and WT mice resulted in elevated bone Fgf23 mRNA expression. Analysis of the circulating forms of FGF23, using an assay that detects the bioactive intact FGF23, revealed that WT and ADHR mice, receiving the control diet, and WT mice, receiving the low iron diet, had a similar, normal intact FGF23 concentration. In contrast, a significant proportion of the iron deficient ADHR mice had elevated intact FGF23, and many had concentrations that were inappropriately normal, relative to the hypophosphatemia that strongly suppresses FGF23. In contrast, measurement of the serum FGF23, using a C-terminal assay that detects the intact and C-terminal fragments of FGF23, documented that both the iron deficient ADHR and WT mice had similarly elevated ‘total’ FGF23 [16]. These data are consistent with the concept that the WT mice maintain normal phosphate metabolism, despite increased FGF23 production, through the proteolytic cleavage of the intact FGF23 protein, a regulatory step aberrant in the ADHR mice due to the R176Q mutation. Consistent with the hypophosphatemia and elevated intact FGF23 level, the iron deficient ADHR mice had significant osteomalacia in cortical and cancellous bone, whereas WT mice, with normal phosphate metabolism and intact FGF23, had normal bone mineralization [16]. Further, the mice showed osteocytic lesions, similar to those observed in XLH. These observations indicate that iron deficiency can enhance FGF23 production in the osteocytes, and may underlie penetrance of ADHR in females during puberty and following pregnancy, when a decreased iron load is often manifest. Data from recent studies in patients with ADHR, which show that circulating levels of C-terminal and intact FGF23 negatively correlate with serum iron concentrations, confirm that iron deficiency regulates FGF23 production.

Although the mechanism by which iron deficiency regulates FGF23 production remains unknown, several studies have identified that the hypoxia induced factor (HIF) family of transcription factors is critical for cellular responses to iron deficiency in bone, and consequent normal growth and development [17] and [18]. Using UMR-106 cells, Farrow et al. [16] found that stabilization of the HIF1α protein with the HIF activator, l-mimosine, increased FGF23 mRNA, with similar results on FGF23 mRNA occurring in the presence of chelation-mediated iron deficiency [16]. The enhanced FGF23 mRNA production was blocked by MEK inhibitors and actinomycin D, consistent with activation of the FGF23 gene during iron deficiency [16]. Despite these observations, however, the molecular pathway(s) that controls FGF23 during iron deficiency in osteocytes (osteoblasts) remains unknown.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing for ADHR focuses upon investigating the FGF23 residues R176 and R179, since alteration of the amino acids at these positions by missense mutations causes this disease. It is important to test for such mutations in youths with hypophosphatemia, since such testing may distinguish early-onset ADHR patients from those with XLH. These results could affect treatment as iron may now be more carefully monitored in ADHR, and waxing and waning of the ADHR disease symptoms could have implications for adjusting phosphate and calcitriol treatment doses. If FGF23 mutations are not identified, ADHR is excluded. However, the absence of mutations in PHEX, and DMP1 exons, does not exclude XLH or ARHR, since mutations and deletions in non-coding regions could result in loss of gene function in these diseases. Such negative results, however, are also consistent with the possible presence of tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO), requiring in some cases the pursuit of imaging studies to identify the presence of the underlying tumor causing this disease.

Autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets

Clinical presentation

Recently, several families have been identified in which affected individuals manifest clinical, biochemical, and bone histomorphometic parameters similar to those observed in XLH and ADHR. However, inspection of the pedigrees of origin suggested an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance in known or suspected consanguineous kindreds [17] and [18]. Further studies revealed that homozygous mutations in the gene encoding DMP1 (dentin matrix protein 1), a non-collagenous phosphoprotein, were associated with this autosomal recessive disease, which has become known as autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR). In comparison to other forms of hereditable hypophosphatemic rachitic diseases, ARHR is extremely rare and has been described in fewer than 10 kindreds worldwide [19], [20], [21] and [22].

Like other forms of hereditable hypophosphatemic diseases, the primary symptoms include lower limb deformities (bowed legs or knock-knees), waddling gait, short stature or stunted growth, tooth abscesses, and bone and muscle pain. However, unlike in XLH, these symptoms appear to depend largely upon the severity and chronicity of the associated phosphate depletion and hypophosphatemia [22].

The biochemical abnormalities of ARHR include hypophosphatemia, due to abundant renal phosphate excretion, and inappropriately low or normal levels of 1,25(OH)2D, relative to the prevailing serum phosphate level. Generally, the serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels and the urinary calcium excretion are within the normal range, but the circulating level of alkaline phosphatase is increased. Like in ADHR, an elevated serum FGF23 is the primary causal factor for the renal phosphate wasting and the attendant hypophosphatemia [17]. However, a wide range of serum FGF23 levels (high, normal, or low) have been reported [17], [18], [19], [20] and [21]. The cause for such variability remains unknown, albeit it is possible that in some patients a normal or low level of circulating FGF23 results from suppression of hormone production by severe hypophosphatemia.

Radiographs of the lower extremities in affected patients generally exhibit cupping, metaphyseal fraying, and bowing of the femurs. Additional X-ray findings are occasionally encountered and include osteosclerosis at the base of the skull, rib and long bone hyperostosis, complete spinal ankylosis and degenerative arthritis [22].

Genetic abnormality

ARHR is due to the inactivating mutations of DMP1, which is located on the long (q) arm of human chromosome 4 at position 21 (4q21). In all reported cases, a point mutation or deletion in the coding region, or splice-site mutations in the 5′ portion of the gene resulted in a loss of function in the DMP1 gene, due to a homozygous frameshift or a premature stop codon (Fig. 2). All of these mutations occurred in the 57-kDa C-terminal fragment of the DMP1 protein, suggesting the functional domain of the molecule (see below).

Fig. 2.

Schematic structure of the human DMP1 gene and its mutations. The DMP1 gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 4 at position 21 (4q21). All seven different mutations showed loss-of-function mutations in the DMP1 gene.

The biochemistries and bone histomorphology in affected subjects with several of these mutations (1484–1490del; 362delC; and 55-IG→C) were typical of the characteristic abnormalities of the ARHR syndrome related above. However, several reports indicate that phenotypic variation occurs, dependent on the site and size of the mutation and the duration of time that affected subjects are without treatment. For example, Farrow et al. [19] reported that subjects, harboring a large biallelic deletion of DMP1 (c.1 A>G, p.M1V), had more severe disease. They displayed not only characteristic hypophosphatemia, rickets, osteomalacia, and stunted growth, but also nerve deafness, facial and dental abnormalities, and learning disabilities as well. In concert, Turan et al. [20] described a family with ARHR, caused by a novel homozygous frameshift mutation (c.485del; p. Glu 163ArgfsX53) in exon 6, resulting in a premature stop codon. Affected children had a unique phenotype including biochemical and radiographic findings typical for ARHR, as well as additional bone and tooth abnormalities comprised of: 1) shortening and broadening of the metacarpals and the proximal and distal phalangial bones; 2) wide pulp chambers and thin dentin in unerupted normally sized and shaped teeth and roots; and 3) diminished enamel thickness in erupted teeth, indicating rapid post-eruption attrition. More recently, Mäkitie et al. [22] described a family with a novel mutation of the splice acceptor junction of DMP1, exon 6 (IVS5-1G>A), which, in association with several downstream cryptic splice acceptor sites, likely alters pre-mRNA splicing and shifts the open-reading frame, if the resulting message is stable, thereby severely compromising DMP1 production. Affected subjects with this mutation, who were > 60 years of age and without treatment, had skeletal abnormalities similar, but more severe, to those reported by Turan et al. [20]. The severe skeletal abnormalities included not only osteomalacia, but also a progressive skeletal dysplasia, characterized clinically by short stature, joint pain, contractures, and immobilization of the spine, and radiographically by short and deformed long bones, significant cranial hyperostosis, enthesopathies, and calcifications of the paraspinal ligaments. Similar to patients with the large biallelic deletion of the DMP1 gene (c.1 A>G, p.M1V), these subjects also had hearing impairment, and dental anomalies resulting in abscess formation. Interestingly, subjects, heterozygous for the gene mutation, had mild hypophosphatemia and focal osteomalacia without clinical evidence of skeletal dysplasia, representing the first expression of the ARHR phenotype in individuals harboring only a heterozygous mutation. This finding is in accord with mouse studies, in which Dmp1 heterozygous null mice display minor mineralization abnormalities of bone [23].

A recent report indicates that autosomal recessive inheritance of rickets is not always associated with DMP1 mutations, but may occur due to a homozygous mutation of ENPP1, a key gene that regulates extracellular phyrophosphate production. In this kindred, with characteristic biochemical and radiographic abnormalities, ENPP1 contained an inactivating mutation arising from a phenylalanine substitution for the strictly conserved tyrosine in position 901, within the nuclease-like domain [24]. Disease due to the ENPP1 mutation has been named ARHR2.

Molecular genetics and animal models

Studies of ARHR in humans and animal models have provided the opportunity to perform mechanistic studies and determine the physiological basis for the pathological abnormalities in affected subjects. Dmp1 null mice essentially capture most, if not all, of the clinical, biochemical, radiological and bone pathological abnormalities evident in ARHR patients [17], [23] and [25]. However, subtle differences do exist between the mouse model and affected humans [17], [18], [19], [20] and [22].

Studies on the genesis of the ARHR disease in the Dmp1 null mice have sorted the effects of: 1) FGF23 dependent hypophosphatemia; and 2) the direct effects of DMP1, providing an important basis for the interlinking of the hereditable hypophosphatemic diseases. In this regard, restoring serum Pi to control levels in the Dmp1-null mouse corrects the mineralization defect at the growth plate, with marked improvement in the bone formation rate, consistent with healing of the rickets [17], [26] and [27]. However, normalization of serum Pi only improves the osteomalacia, and the bone phenotype is not completely rescued. Taken together, these data suggest that rickets in ARHR is due to FGF23-mediated hypophosphatemia, whereas the principal cause of the osteomalacia is defective mineralization, resulting from a lack of functional DMP1.

Studies in the Dmp1 null mouse provided evidence for such a direct effect. Lu et al. [28] separately re-expressed full length DMP1 and the 57-kDa C-terminal fragment, the likely functional domain of the protein, in the Dmp1 null mouse osteoblasts/osteocytes. Not only did the full length DMP1 successfully rescue the phenotype, including growth plate defects, osteomalacia, abnormal osteocyte maturation, and serum biochemistries (e.g. FGF23 and phosphate), but the 57-kDa C-terminal fragment had a similar rescue efficiency. In contrast, re-expression of mutated full-length DMP1, resistant to cleavage, failed to rescue the biochemical and bone abnormalities characteristic of ARHR [29] and [30]. These observations confirm that full-length DMP1 is an inactive precursor and the DMP1 57-kDa fragment is the key functional domain of the protein. Moreover, the data indicate that DMP1 not only regulates the production of FGF23, but also, independent of FGF23 mediated hypophosphatemia, promotes bone mineralization as well.

Recent studies indicate that the effects of DMP1 on bone mineralization are mediated by Wnt/β-catenin expression, which is elevated in the Dmp1 null mouse, secondary to suppressed production of DKK1. Indeed, normalization of β-catenin expression in the Dmp1 null mouse by overexpression of DKK1 improves the bone formation rate and bone mineralization, significantly healing the osteomalacia [31]. In concert, over-expression of the 57-kDa C-terminal DMP1 fragment normalizes DKK1 production [28].

The abnormal bone mineralization in ARHR may also relate to other notable effects of DMP1. Indeed, one of the most striking changes in Dmp1 null mice is defective osteocyte morphology and function. Recent studies indicate that these abnormalities are due to the loss of DMP1 function, which disrupts normal osteoblast to osteocyte maturation, a potential contributing factor to the abnormal bone mineralization [27].

Despite the strong evidence that the Dmp1 null mouse is a murine model of ARHR, subtle differences, including only mild hypophosphatemia and moderately elevated levels of FGF23, have been observed in affected patients. To determine whether this difference is due to mutant DMP1 retaining partial function, a transgenic mouse model with the same human Dmp1 C-terminal deletion mutation (1484–1490del mutation) was created, and crossed to the Dmp1 null background. Consistent with the retention of partial function in the human mutant DMP1, this mouse line displays only mild hypophosphatemic rickets, confirming that the Dmp1 null mouse is indeed a murine model of ARHR [32].

Collectively, these observations indicate that osteocyte regulation of phosphate homeostasis is FGF23 dependent, while that of bone mineralization is due to FGF23 mediated hypophosphatemia and the independent effects of DMP1, mediated by abnormalities in Wnt/β-catenin expression and perhaps abnormal osteoblast maturation. In XLH, regulation of phosphate homeostasis and bone mineralization occurs through a remarkably similar mechanism (see below).

Genetic testing

Diagnosis of ARHR requires DNA sequencing of leukocytes present in a small blood sample of patients. The coding sequences of DMP1 are amplified through PCR reactions, and all products are fully sequenced. The results are analyzed and interpreted based on recent publications.

X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets

Clinical presentation

XLH, a disease with an incidence of 1:20,000 live births, is the prototypic heritable renal phosphate wasting disorder, characterized by skeletal abnormalities of variable severity and growth retardation. The syndrome is an X-linked dominant disorder with complete penetrance of a renal tubular abnormality, resulting in reduced renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate and consequent hypophosphatemia. The phenotypic spectrum of XLH ranges from isolated hypophosphatemia to severe lower extremity bowing [33]. Generally, in children clinically evident manifestations include short stature and bowing of the lower extremities. In addition, enlargement of the wrists and/or knees secondary to rickets commonly occurs. These features are often not apparent until 6–12 months of age or older [34]. In adults, enthesopathy (calcification of the tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules) may be the initial presenting complaint [35]. Affected youths and adults have a normal serum 25(OH)D level and a 1,25(OH)2D concentration inappropriately normal relative to the prevailing hypophosphatemia, indicative of abnormally regulated renal 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase activity in the renal proximal convoluted tubule. Bone biopsies in both affected children and adults reveal low turnover osteomalacia, the severity of which has no relationship to gender, the severity of the biochemical abnormalities or the degree of the clinical disability.

Genetic abnormality

Extensive studies of multigenerational pedigrees led to identification of the genetic defect underlying XLH in the Xp22.1-p21 region of the X chromosome. Subsequent investigations resulted in cloning and identification of the disease gene as PHEX, a PHosphate regulating gene with homologies to Endopeptidases located on the X-chromosome [36], [37], [38], [39], [40] and [41]. The gene encodes a 749-amino acid protein, consisting of a small aminoterminal intracellular tail, a single, short transmembrane peptide, and a large carboxyterminal extracellular peptide with a motif typical of zinc metalloproteases. The similarity of PHEX with metalloproteases resulted in inclusion of this protein in the M13 family of membrane-bound metalloproteases, which are membrane bound glycoproteins.

Cloning of PHEX was followed quickly by cloning of the homologous Phex gene in the murine homologs of XLH, hyp- and gy-mice, and identification of the gene mutations in these animal models [42] and [43]. Investigation of the murine tissues from these models revealed that PHEX is predominantly expressed in bones and teeth, although mRNA, protein, or both, have also been reported in the lung, brain, muscle, gonads, skin and parathyroid glands. The cellular localizations of the PHEX in bone and teeth are in the osteoblast/osteocytes and the odontoblast/ameloblast, respectively, with subcellular locations at the cell surface membrane, the endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi compartment.

To date > 280 different PHEX mutations have been documented in patients with XLH [44]. These mutations are scattered throughout exons 2–22 and consist of deletions, frameshifts, insertions, and duplications, as well as splice site, frameshift, nonsense and missense abnormalities [45]. The PHEX mutations are present in > 90% of probands from selected kindreds, in which an evident X-linked dominant pattern of inheritance is present. Although all of these mutations invariably cause loss of function, the mechanism(s) by which such loss of activity occurs remains unknown, albeit interference with protein trafficking, resulting in protein sequestration in the endoplasmic reticulum, has been suggested. In select probands without demonstrable mutations in the PHEX coding region, intron mutations, resulting in mRNA splicing abnormalities, have been identified.

Although efforts to rescue the HYP phenotype by transgenic PHEX overexpression have been unsuccessful, recent studies have not only unambiguously confirmed the role of inadequate Phex expression in the genesis of XLH, but established the physiologically relevant gene mutation site in this disease. Using mice with conditional osteocalcin-promoted (OC-promoted) Phex inactivation in osteoblasts, Yuan et al. [46] showed that Oc-Cre-PhexΔflox/y mice exhibit biochemical and bone histological abnormalities indistinguishable from those in hyp-mice, providing compelling evidence that aberrant PHEX function in osteoblasts alone is sufficient to underlie the HYP phenotype.

Molecular genetics and animal models

While the PHEX gene defect clearly underlies XLH, only recently have investigators gained insight into the complex mechanism by which PHEX regulates expression of the HYP phenotype. Currently, investigators generally agree that the primary inborn error in XLH results in an expressed abnormality in the renal proximal tubule, which impairs Pi absorption. Nevertheless, controversy has existed on whether this renal abnormality is primary or secondary to the elaboration of a hormonal factor. However, recent studies have provided compelling evidence that the defect is secondary to the effects of a circulating hormone or metabolic factor. Most notably, the humoral basis of XLH was supported by experiments in which cross-transplantation of kidneys in normal and hyp-mice resulted in neither transfer of the mutant phenotype nor its correction, unequivocally establishing the hormone dependence of phosphate wasting in this disorder [47].

Subsequent investigations into the pathogenesis of XLH have focused on identifying the metabolic factor(s) underlying the disease, as well as the source and regulation of its secretion. These studies argue that a circulating factor(s), phosphatonin(s), plays an important role in the pathophysiological cascade responsible for XLH. Elucidating the role of FGF23 in the pathogenesis of ADHR provided the first link to integrating the pathogenesis of the heritable hypophosphatemic diseases. The search for the circulating phosphatonin underlying XLH clarified this inter-linkage. Initial studies in patients with XLH and the hyp-mouse identified abnormal production or circulating levels of several phosphatonin(s), including FGF23, sFRP4, MEPE, and FGF7. However, further investigations established that, as in ADHR and ARHR, FGF23 plays a singular role in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis in XLH. The data supporting this conclusion include the following: 1) transgenic mice overexpressing FGF23, under the control of the α1(I) collagen promoter, exhibit growth retardation, osteomalacia, and disturbed phosphate homeostasis, consistent with the abnormalities in patients with XLH and in hyp-mice [48]; 2) affected patients and mutant mice exhibit increased circulating levels of FGF23 [49] and [50]; 3) the increased circulating levels of FGF23 in hyp-mice result both from inhibited degradation of full-length FGF23 to biologically inactive products (as in ADHR) and enhanced production of FGF (as in ARHR [see below]) [46]; 4) deletion of Fgf23 from hyp-mice reverses the HYP phenotype [50]; and 5) selective deletion of Phex in the osteoblast results in increased circulating levels of FGF23 (and not other phosphatonins) and creates an animal model with renal and bone phenotype abnormalities characteristic of XLH [46]. These observations establish that increased bone production and serum levels of MEPE, sFRP4, and FGF7 are not critical for development of the classical HYP phenotype, whereas increased bone production and decreased proteolysis of FGF23, and consequent elevation of serum FGF23 concentration appear requisite for this biological function. Collectively, these data suggest that FGF23 is the phosphatonin pivotal to the pathogenesis of XLH, as well as ADHR and ARHR (see below).

Despite these advances, the mechanism(s) by which loss of PHEX function alters degradation and production of FGF23 was not immediately apparent. Indeed, until recently efforts have failed to definitively identify a substrate for the protein and/or characterize the downstream effects of PHEX, which result in the classical renal and bone phenotype in XLH. In fact, several studies have excluded FGF23 as a PHEX substrate. However, over the past 2 years the downstream PHEX-dependent effects that modulate FGF23 production and degradation have been elucidated. These studies revealed that FGF23 degradation and production, which occur primarily in the osteocyte/osteoblast, are regulated by 7B2 and PC2, and the activity of the heterodimer 7B2·PC2. Yuan et al. [11] documented that a decrease in the 7B2 chaperone protein (Signe) mRNA in hyp-mouse osteocytes/osteoblasts, and consequent diminished 7B2·PC2 enzyme activity, directly limit FGF23 degradation and indirectly enhance Fgf23 mRNA production. Enhanced FGF23 production is mediated by a downstream effect of decreased 7B2·PC2 enzyme activity, impaired DMP1 degradation, and a resultant deficiency of the 57-kDa C-terminal proteolytic DMP1 fragment, which results in increased Fgf23 mRNA. More recently, additional studies have revealed that the decreased osteocyte/osteoblast 7B2·PC2 enzyme activity in hyp-mice also decreases the Dkk1 mRNA and protein in bone, resulting in increased Wnt/β-catenin expression (unpublished observations), an abnormality manifest in the Dmp1 null mouse, the murine homologue of ARHR (see above). Further observations indicate that in the hyp-mouse, like in the Dmp1 null mouse, the mineralization abnormality in the bone growth plates is phosphate dependent, whereas the mineralization abnormalities in cortical and trabecular bone result from the integrated effects of FGF23 mediated hypophosphatemia and increased Wnt/β-catenin expression. These observations remarkably enhance our understanding of the interlinkage between the heritable hypophosphatemic diseases. In ADHR and XLH, impaired degradation of FGF23 increases the circulating concentration of the biologically active intact protein, while in XLH and ARHR, enhanced Fgf23 mRNA production results from a deficiency of the functional 57-kDa C-terminal fragment of DMP1. The resultant FGF23 mediated hypophosphatemia underlies the rickets in each of the heritable hypophosphatemic diseases and contributes to the osteomalacic disorder, which is principally due to the 57-kDa DMP1 dependent increase in Wnt/β-catenin expression.

Genetic testing

Since the clinical presentation of familial hypophosphatemic rachitic/osteomalacic disorders is remarkably similar, establishing the diagnosis of XLH depends, in general, upon ascertaining the pattern of family inheritance. Male-to-male transmission of disease excludes XLH, and presence of the disease in the parent of an affected subject excludes ARHR. Not infrequently, however, knowledge about the pattern of family inheritance is incomplete or misleading because of absent knowledge about the family of an affected subject, a missed diagnosis in the mother of an affected proband, secondary to expression of a mild form of the disease, or the relatively frequent occurrence of a spontaneous mutation. Ascertaining diagnosis in such cases is often related to the need to provide accurate genetic counseling or offer a unique therapeutic intervention. The choice of therapy for XLH is combination treatment with phosphate and calcitriol. Other related diseases, particularly ADHR, may require less aggressive treatment or therapy with alternative drugs, such as iron. In such circumstances, unambiguous diagnosis of XLH may be beneficial. The appropriate genetic testing for the diagnosis of XLH is commercially available at laboratories worldwide, including: 1) GeneDx, Gaitherburg, MD; 2) Athena Diagnostics Inc., Worcester, MA; 3) Center for Human Genetics, Ingelheim, Germany; 4) University Hospital Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium; and 5) Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter, United Kingdom. In addition, numerous research laboratories are equipped to perform mutation analysis of the PHEX gene, which would permit diagnosis of XLH.

Conclusions

ADHR, ARHR, and XLH represent three related heritable hypophosphatemic diseases that arise, in part, from mutations in, or dysregulation of, a common gene product FGF23. A summary of the pathogenetic models for these diseases is provided below.

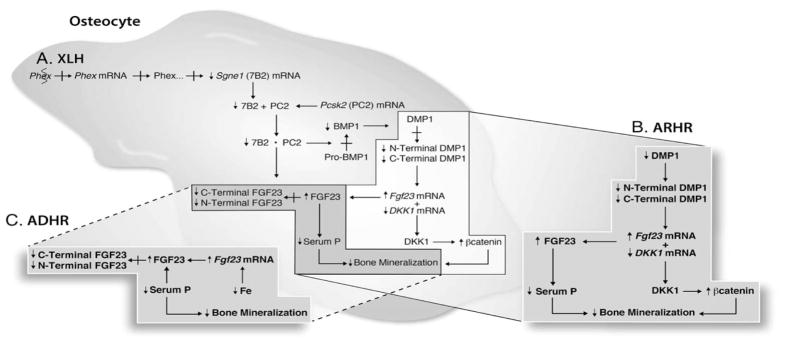

Pathogenetic model for the heritable hypophosphatemic rachitic/osteomalacic diseases (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

The inter-related biomolecular abnormalities underlying the abnormal phosphate homeostasis and bone mineralization in XLH, ARHR, and ADHR. A. In XLH, the PHEX mutation results in suppression of Sgne1 (7B2) mRNA, by an as yet unknown mechanism. The resultant decreased 7B2 protein leads to decreased 7B2·PC2 enzyme activity, which directly limits FGF23 degradation, and through effects on BMP1 decreases DMP1 degradation. The restricted production of the C-terminal DMP1 peptide increases Fgf23 mRNA and decreases DKK1 mRNA. Together the limited FGF23 proteolysis and enhanced Fgf23 mRNA increase intact bioactive FGF23, which in turn results in renal phosphate wasting and hypophosphatemia. The decreased DKK1 mRNA and DKK1 protein enhance Wnt/β-catenin protein production, which, along with FGF23 mediated hypophosphatemia, impairs bone mineralization. B. In ARHR, the abnormal renal phosphate wasting and bone mineralization occur as a consequence of a DMP1 mutation that limits the production of the DMP1 protein. These phenotypic characteristics result from the same abnormal biomolecular events, as those that occur in response to the deficiency of the C-terminal DMP1 peptide in XLH. C. In ADHR, the abnormal renal phosphate wasting and bone mineralization occur as a consequence of a FGF23 mutation that limits FGF23 degradation at the subtilisin-like protein convertase enzyme site. In XLH, similar limited FGF23 proteolysis occurs due to decreased 7B2·SPC2 enzyme activity. Iron deficiency in patients with ADHR may increase Fgf23 mRNA, contributing to the increased serum FGF23 levels in this disease.

An activating FGF23 mutation limits proteolysis of the bioactive full length protein → ↑serum FGF23 → ADHR

An inactivating DMP1 mutation decreases the active C-terminal functional domain of the protein → ↑serum FGF23 (↑FGF23 mRNA) and ↑WNT/β-catenin (↓DKK1 mRNA/protein) → ARHR

An inactivating PHEX mutation decreases Sgne1 (7B2) mRNA/protein, and the resultant decreased 7B2·PC2 activity mediates downstream events → ↑serum FGF23 (↓FGF23 proteolysis and ↑FGF23 mRNA/protein) and ↑WNT/β-catenin (↓DKK1 mRNA/protein) → XLH.

This model documents that alterations in FGF23 are common to the universal disease phenotype. However, variations in the disease specific phenotype are predictable, and likely related to either the magnitude of FGF23 dysregulation or the effects of PHEX/DMP1 on Wnt/β-catenin and possibly other factors that regulate bone mineralization.

Understanding the pathogenetic models outlined above, including the entry points capable of regulating FGF23 expression, increases the targets for therapy of these disorders. As a result, in addition to genetic rescue of the phenotype, it is theoretically possible to direct therapy at modulating osteocyte response to the various mutations. For example, in XLH a therapeutic intervention to increase osteocyte (osteoblast) 7B2 production would prevent the diminished 7B2·PC2 activity and preclude genesis of an increased serum FGF23 concentration and increased β-catenin, limiting phenotypic expression of the disease. Indeed, recent studies have indicated that Hexa-d-arginine administration to hyp-mice enhances osteocyte 7B2 production and rescues the HYP phenotype [11]. In ARHR it is plausible that therapy aimed at enhancing DKK1 production and phosphate administration would similarly provide a rescue for the disease phenotype.

These observations provide the first insight to the possibility that management of the endocrine role of osteocytes may play an important role in therapy of human diseases. As further information is developed about osteocyte function, it seems likely that potential treatment strategies for diseases, beyond those related to phosphate metabolism and bone mineralization, will become apparent.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grants to MK Drezner (AR27032, 2UL1TR000427), JQ Feng (DE018486), and KE White (DK063934, AR059278) and a GRIP Award from Sanofi-Genzyme to KE White.

References

- 1.Bonewald LF. Osteocytes as dynamic multifunctional cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;6:281–290. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin A, Liu S, David V, Li H, Karydis A, Feng JQ, Quarles LD. Bone proteins PHEX and DMP1 regulate fibroblastic growth factor Fgf23 expression in osteocytes through a common pathway involving FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling. FASEB J. 2011;25:2551–2562. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchine JW, Stambler AA, Harrison HE. Familial hypophosphatemic rickets showing autosomal dominant inheritance. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1971;7:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Econs MJ, McEnery PT. Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia: clinical characterization of a novel renal phosphate-wasting disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:674–681. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Econs MJ, McEnery PT, Lennon F, Speer MC. Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is linked to chromosome 12p13. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2653–2657. doi: 10.1172/JCI119809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ADHR-Consortium. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations in FGF23. Nat Genet. 2000;26:345–348. doi: 10.1038/81664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribaa M, Younes M, Bouyacoub Y, Korbaa W, Ben Charfeddine I, Touzi M, et al. An autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets phenotype in a Tunisian family caused by a new FGF23 missense mutation. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:111–115. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molloy SS, Bresnahan PA, Leppla SH, Klimpel KR, Thomas G. Human furin is a calcium-dependent serine endoprotease that recognizes the sequence Arg-X-X-Arg and efficiently cleaves anthrax toxin protective antigen. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16396–16402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama K. Furin: a mammalian subtilisin/Kex2p-like endoprotease involved in processing of a wide variety of precursor proteins. Biochem J. 1997;327(Pt 3):625–635. doi: 10.1042/bj3270625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benet-Pages A, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Zischka H, White KE, Econs MJ, Strom TM. FGF23 is processed by proprotein convertases but not by PHEX. Bone. 2004;35:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan B, Feng JQ, Bowman S, Liu Y, Blank RD, Lindberg I, et al. Hexa-d-arginine treatment increases 7B2 PC2 activity in hyp-mouse osteoblasts and rescues the HYP phenotype. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:56–72. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White KE, Carn G, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Benet-Pages A, Strom TM, Econs MJ. Autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) mutations stabilize FGF-23. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2079–2086. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimada T, Muto T, Urakawa I, Yoneya T, Yamazaki Y, Okawa K, et al. Mutant FGF-23 responsible for autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is resistant to proteolytic cleavage and causes hypophosphatemia in vivo. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3179–3182. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imel EA, Hui SL, Econs MJ. FGF23 concentrations vary with disease status in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:520–526. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durham BH, Joseph F, Bailey LM, Fraser WD. The association of circulating ferritin with serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor-23 measured by three commercial assays. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44:463–466. doi: 10.1258/000456307781646102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrow EG, Yu X, Summers LJ, Davis SI, Fleet JC, Allen MR, et al. Iron deficiency drives an autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) phenotype in fibroblast growth factor-23 (Fgf23) knock-in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1146–E1155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110905108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B, et al. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pages A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, Muller-Barth U, et al. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/ng1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrow EG, Davis SI, Ward LM, Summers LJ, Bubbear JS, Keen R, et al. Molecular analysis of DMP1 mutants causing autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets. Bone. 2009;44:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turan S, Aydin C, Bereket A, Akcay T, Guran T, Yaralioglu BA, et al. Identification of a novel dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP-1) mutation and dental anomalies in a kindred with autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia. Bone. 2010;46:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koshida R, Yamaguchi H, Yamasaki K, Tsuchimochi W, Yonekawa T, Nakazato M. A novel nonsense mutation in the DMP1 gene in a Japanese family with autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:585–590. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mäkitie O, Pereira RC, Kaitila I, Turan S, Bastepe M, Laine T, et al. Long-term clinical outcome and carrier phenotype in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia caused by a novel DMP1 mutation. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2165–2174. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling Y, Rios HF, Myers ER, Lu Y, Feng JQ, Boskey AL. DMP1 depletion decreases bone mineralization in vivo: an FTIR imaging analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2169–2177. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito T, Shimizu Y, Hori M, Taguchi M, Igarashi T, Fukumoto S, et al. A patient with hypophosphatemic rickets and ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament caused by a novel homozygous mutation in ENPP1 gene. Bone. 2011;49:913–916. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye L, Mishina Y, Chen D, Huang H, Dallas SL, Dallas MR, et al. Dmp1-deficient mice display severe defects in cartilage formation responsible for a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6197–6203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412911200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, Li Z, et al. Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19141–19148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang R, Lu Y, Ye L, Yuan B, Yu S, Qin C, et al. Unique roles of phosphorus in endochondral bone formation and osteocyte maturation. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1047–1056. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Yuan B, Qin C, Cao Z, Xie Y, Dallas SL, et al. The biological function of DMP-1 in osteocyte maturation is mediated by its 57-kDa C-terminal fragment. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:331–340. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Prasad M, Gao T, Wang X, Zhu Q, D’Souza R, et al. Failure to process dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) into fragments leads to its loss of function in osteogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31713–31722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Lu Y, Chen L, Gao T, D’Souza R, Feng JQ, et al. DMP1 processing is essential to dentin and jaw formation. J Dent Res. 2011;90:619–624. doi: 10.1177/0022034510397839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin S, Jiang Y, Zong Z, Liu M, Liu Y, Yuan B, et al. A key pathological role for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang B, Cao Z, Lu Y, Janik C, Lauziere S, Xie Y, et al. DMP1 C-terminal mutant mice recapture the human ARHR tooth phenotype. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruppe MD. X-linked hypophosphatemia. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP, editors. GeneReviews [Internet] University of Washington; Seattle, Seattle (WA): 2012. [1993–2012 Feb 09 updated 2012 Sep 27] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison HE, Harrison HC, Lifshitz F, Johnson AD. Growth disturbance in hereditary hypophosphatemia. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:290–297. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1966.02090130064005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polisson RP, Martinez S, Khoury M, Harrell RM, Lyles KW, Friedman N, et al. Calcification of entheses associated with X-linked hypophosphatemic osteomalacia. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507043130101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The HYP Consortium. A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Nat Genet. 1995;11:130–136. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Econs MJ, Fain PR, Norman M, Speer MC, Pericak-Vance MA, Becker PA, et al. Flanking markers define the X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets gene locus. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1149–1152. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Econs MJ, Rowe PS, Francis F, Barker DF, Speer MC, Norman M, et al. Fine structure mapping of the human X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets gene locus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1351–1354. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.5.7962329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Econs MJ, Francis F, Rowe PS, Speer MC, O’Riordan JL, Lehrach H, et al. Dinucleotide repeat polymorphism at the DXS1683 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:680. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francis F, Rowe PS, Econs MJ, See CG, Benham F, O’Riordan JL, et al. A YAC contig spanning the hypophosphatemic rickets disease gene (HYP) candidate region. Genomics. 1994;21:229–237. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowe PS, Goulding JN, Francis F, Oudet C, Econs MJ, Hanauer A, et al. The gene for X-linked hypophosphataemic rickets maps to a 200–300 kb region in Xp22.1, and is located on a single YAC containing a putative vitamin D response element (VDRE) Hum Genet. 1996;97:345–352. doi: 10.1007/BF02185769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck L, Soumounou Y, Martel J, Krishnamurthy G, Gauthier C, Goodyer CG, et al. Pex/PEX tissue distribution and evidence for a deletion in the 3′ region of the Pex gene in X-linked hypophosphatemic mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1200–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI119276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strom TM, Francis F, Lorenz B, Boddrich A, Econs MJ, Lehrach H, et al. Pex gene deletions in Gy and Hyp mice provide mouse models for X-linked hypophosphatemia. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:165–171. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabbagh Y, Tenenehouse HS. PHEXdb. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200007)16:1<1::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-J. http://www.phexdb.mcgill.ca. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Rowe PS, Oudet CL, Francis F, Sinding C, Pannetier S, Econs MJ, et al. Distribution of mutations in the PEX gene in families with X-linked hypophosphataemic rickets (HYP) Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:539–549. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan B, Takaiwa M, Clemens TL, Feng JQ, Kumar R, Rowe PS, et al. Aberrant Phex function in osteoblasts and osteocytes alone underlies murine X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:722–734. doi: 10.1172/JCI32702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nesbitt T, Coffman TM, Griffiths R, Drezner MK. Crosstransplantation of kidneys in normal and Hyp mice: evidence that the Hyp mouse phenotype is unrelated to an intrinsic renal defect. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1453–1459. doi: 10.1172/JCI115735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimada T, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Hino R, Yoneya T, et al. FGF-23 transgenic mice demonstrate hypophosphatemic rickets with reduced expression of sodium phosphate co-transporter type IIa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamazaki Y, Okazaki R, Shibata M, Hasegawa Y, Satoh K, Tajima T. Increased circulator level of biologically active full-length FGF-23 in patients with hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4957–4960. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu S, Zhou J, Tang W, Jiang X, Rowe DW, Quarles LD. Pathogenic role of Fgf23 in Hyp mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E38–E49. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00008.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]