Abstract

Background

The purpose of the current study was to examine the factorial dimensions underlying Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) in a large ethnically and economically diverse sample of postpartum women and to assess their relative contribution in differentiating clinical diagnoses in a subsample of depressed women.

Methods

We administered the BDI-II to 953 women between 4 and 20 weeks postpartum. Women who had low (1–7) and high (> 12) BDI-II total scores were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).

Results

Exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) revealed three factors, Cognitive, Somatic, and Affective, that accounted for 49.09% of the overall variance of items. Logistic regression analyses showed that somatic and affective factors contributed to diagnosis of major depression, while the somatic factor alone contributed to the diagnosis of depression with comorbid anxiety. The cognitive factor differentiated women with major depression from women who were never depressed.

Limitations

Our definition of clinical depression included episodes of depression during the child’s lifetime, and depressive symptoms were not necessarily current at the time of the assessment, which may impact the relative contribution of BDI-II factors to clinical diagnosis.

Conclusion

Conceptualizing the structure of the BDI-II using these three factors could contribute to refining the measurement and scoring of depressive symptomatology and severity in postpartum women. Although somatic symptoms of depression may be difficult to differentiate from the physiological changes of normative postpartum adjustment, our results support the inclusion of somatic symptoms of depression in the calculation of a BDI-II total score.

Keywords: Depression, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Postpartum Depression, Clinical diagnoses, Factor analysis, Structural Equation Modeling

Introduction

Depressive symptoms in women after parturition constitute a significant clinical issue. The disability and morbidity associated with postpartum depression make its identification and treatment a public health priority. Identification of depression often relies on self-report inventories that are easily administered and rapidly scored as compared to lengthy clinical interviews. Among the popular measures, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961) and its variants have been widely used in clinical as well as community samples.

The BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996) modified the BDI to address concerns with early versions of the scale (Harris et al., 1989) and to better reflect DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders (Boyd et al., 2005). Although the BDI-II is internally consistent (Bos et al., 2009; Mahmud et al., 2004) and comparable in accurately identifying postpartum depression to other self-report measures (Lee et al., 2001; Tandon et al., 2012), its clinical utility in identifying postpartum depression has been questioned because of the inclusion of somatic symptoms. A number of normal physiological changes of parturition are similar to somatic symptoms of depression and so may inflate total BDI scores in postpartum women who do not otherwise meet the diagnostic criteria of depression (Hopkins et al., 1989; O’Hara et al., 1990). Research has not adequately addressed the relative contributions of somatic and other dimensions underlying BDI-II items to the total score or to the clinical diagnosis of depression in postpartum women. In light of increasing use of BDI-II with postpartum samples and the importance of early depression screening and intervention, there is need to investigate these issues using statistically appropriate and rigorous testing in large samples.

Here we first examine the factor structure of the BDI-II in a large ethnically and economically diverse sample of postpartum women to identify constellations of symptoms that represent dimensions or underlying constructs in this population. We then use these factors to examine their relative contribution in differentiating clinical diagnoses of depression among high scorers.

Factor Structure of BDI-II

Although factor analytic procedures have been reported for the BDI-II in medical, psychiatric, and ethnic groups, no study has examined the factor structure of the English version of BDI-II in a postpartum sample. Table 1 reviews empirical studies with factor analytic procedures on the BDI-II. The review includes studies that generated first-order factor structures as final solutions using standard methods of factor analysis in non-medical samples for full-item versions of BDI-II. We have categorized the studies according to the type of sample (psychiatric, non-clinical, and postpartum), and listed by year of publication within each category. To facilitate interpretation across studies, the order of factors has been interchanged for some studies.

Table 1.

Review of previous BDI-II factor structures

| Clinical Samples

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Beck, Steer, & Brown (1996) | Steer, Kumar, Ranieri, & Beck (1998) | Steer, Ball, Ranieri, & Beck (1999) | Bedi, Koopman, & Thompson (2001) | Osman, Kopper, Barrios, Gutierrez, & Bagge (2004) | Buckley, Parker, & Heggie (2001) |

|

| ||||||

| Sample | Psychiatric Outpatients (N=500) | Adoles Psychiatric Outpatients (N=210) | Depressed Outpatients (N=210) | Women with MDD (N=390) | Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients (N=408) | Substance Abusers (N=416) |

|

| ||||||

| BDI-II Sample Means | 22.45 | 18.23 (Girls=20.63, Boys=15.83) | 28.64 (Men=26.7, Women=30.6) | 29.60 | 17.75 (Girls=20.49, Boys=15.02) | (Afr-Amer=22.1, Caucasian =24.5 |

|

| ||||||

| 1. Sadness | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Pessimism | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Past failure | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Loss of pleasure | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 5. Guilty feelings | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Punishment feelings | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Self-dislike | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Self-criticalness | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Suicidal thoughts or wishes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Crying | 2 | 3&2 | 2 | 2 | none | 2 |

| 11. Agitation | 2 | 2&1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 12. Loss of interest | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 13. Indecisiveness | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 14. Worthlessness | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 15. Loss of energy | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 16. Changes in sleeping pattern | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Irritability | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2&1 | 3 |

| 18. Changes in appetite | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 19. Concentration difficulty | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. Tiredness or fatigue | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 21. Loss of interest in sex | 2 | none | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

|

| ||||||

| Factors (% variance explained) | 1: Cognitive | 1: Cognitive | 1: Cognitive | 1: NegativTheory | 1: Cog-Aff (29.29%) | 1: Cognitive |

|

| ||||||

| 2: Som-Aff | 2: Som-Aff | 2: Non-Cognitive | 2: Loss & Impairment | 2: Som (12.80%) | 2: Affective | |

|

| ||||||

| 3: Guilt/Punishm | 3: Somatic | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Total % Variance Explained | 44% | 42.09% | ||||

| Community Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Study | Beck, Steer, & Brown (1996)1 | Osman, Downs, Barrios, Kopper, Gutierrez, & Chiros (1997)2 | Steer, & Clark (1997) | Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, (1998) | Whisman, Perez, & Ramel, (2000) | Arnau, Meag her, Norris (2001) | Byrne, Stewart, & Lee (2004) |

|

| |||||||

| Sample | Undergraduate College Students (N=120) | Undergraduate College Students (N=230) | Undergraduate College Students (N=160) | Undergraduate College Women (N=328) | Undergraduate College Students (N=576) | Primary Care Medical Patients (N=340) | Hong Kong Community Adolescents (N=486) |

|

| |||||||

| BDI-II Sample Means | 11.09 (Men=9.41, Women=11.88) | 11.86 | 9.11 | 8.36 | 8.74 | 13.12 | |

|

| |||||||

| 1. Sadness | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2&1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 2. Pessimism | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Past failure | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Loss of pleasure | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 5. Guilty feelings | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Punishment feelings | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Self-dislike | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Self-criticalness | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | none | 1 |

| 9. Suicidal thoughts or wishes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Crying | 1 | 1&3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 11. Agitation | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 12. Loss of interest | 1 | 2 | 1&2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 13. Indecisiveness | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 14. Worthlessness | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 15. Loss of energy | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 16. Changes in sleeping pattern | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Irritability | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 18. Changes in appetite | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 19. Concentration difficulty | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1&2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 20. Tiredness or fatigue | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 21. Loss of interest in sex | none | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | not included |

|

| |||||||

| Factors (% variance explained) | 1: Cog-Aff | 1: Negative Attitude | 1: Cog-Aff | 1: Cog-Aff (35%) | 1: Cog-Aff | 1: Cognitive | 1: Negative Attitude |

|

| |||||||

| 2: Somatic | 2: Perf Difficulty | 2: Som (17%) | 2: Som-Veg (6%) | 2: Somatic | 2: Som-Aff | 2: Perf Difficulty | |

|

| |||||||

| 3: Somatic | 3: Somatic | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total % Variance Explained | 45% | 53.50 % | |||||

| Postpartum Samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Study | Mahmud, Awang, Herman, & Mohamed (2004) | Bos, et al. (2009) | Bos, et al. (2009) | Present study |

|

| ||||

| Sample | Postpartum women (N=354) | Postpartum Women (N=354) | Postpartum Women (N=354) | Postpartum Women (N=475) |

|

| ||||

| BDI-II Sample Means | 4.43 | Sample means not provided | Sample means not provided | 10.87 |

|

| ||||

| 1. Sadness | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 2. Pessimism | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Past failure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 4. Loss of pleasure | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 5. Guilty feelings | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 6. Punishment feelings | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 7. Self-dislike | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Self-criticalness | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Suicidal thoughts or wishes | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Crying | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 11. Agitation | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 12. Loss of interest | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 13. Indecisiveness | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 14. Worthlessness | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 15. Loss of energy | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 16. Changes in sleeping pattern | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Irritability | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 18. Changes in appetite | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 19. Concentration difficulty | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. Tiredness or fatigue | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 21. Loss of interest in sex | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|

| ||||

| Factors (% variance explained) | 1: Cognitiv (12.2%) | 1: Som-Anx (21.4%) | 1: Cog-Aff (20.6%) | 1: Cognitive (36.8%) |

|

| ||||

| 2: Affective (16.7%) | 2: Cog-Aff (21.3%) | 2: Som-Anx (19.8%) | 2: Affective (5.0%) | |

|

| ||||

| 3: Somatic (14.6%) | 3: Guilt (9.0%) | 3: Somatic (7.3%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Total % Variance Explained | 43.56% | 42.7% | 49.40% | |

Note: There is sample overlap between Steer, Ball, Ranieri, and Beck’s (1999) study and Bedi, Koopman, and Thompson’s (2001).

Their factor solution is the same as the 2-factor solution obtained by Storch, Roberti, & Roth (2004).

Their factor solution is the same as the 3-factor solution obtained by Carmody (2005).

In psychiatric samples (except Osman et al., 2004), two factors typically represent cognitive and somatic-affective symptoms (Beck et al., 1996; Steer et al., 1999). A similar factor structure is found in nonclinical samples, but affective items load more consistently on the cognitive than the somatic factor (Beck et al., 1996; Dozois et al., 1998; Steer & Clark, 1997; Storch et al., 2004; Whisman et al., 2000). Studies have also found a 3-factor model in psychiatric and non-clinical samples, with the factors variously labeled as cognitive/negative attitude, affective/performance difficulty, and somatic (Byrne et al., 2004; Carmody, 2005; Osman et al., 1997). In studies conducted with medical patients (not included in Table 1), a group that might be considered similar to postpartum samples due to the presence of prominent somatic symptoms, a somatic factor consistently emerges as a factor in 2-or 3-factor solutions (Buckley, et al., 2001; Harris & D’Eon, 2008; Patterson et al., 2011; Poole et al., 2006; Seignourel et al., 2008).

As Table 1 shows, the factor structure differs across studies, and items representing the factors also differ. Other than the few items that always make up the cognitive factor (pessimism, self-criticalness) and the somatic factor (sleep and appetite changes), there is no consistency across studies on the item composition of the factors. In addition, the amount of variance explained by different factors has been inconsistent across studies. In community and clinical samples, the somatic factor (when present) often does not explain as much variance as the cognitive and/or affective factors. However, in postpartum samples (Bos et al., 2009; Mahmud et al., 2004), the somatic factor explains a large portion of the variance.

Only two studies have explored the factor structure of BDI-II in postpartum women. Mahmud et al. (2004) used a Malay-version of the BDI-II and generated a 3-factor structure: somatic, cognitive, and affective. Bos et al. (2009) used a Portuguese version of the BDI-II and identified 2-and 3-factor solutions. Although a somatic factor emerged as one factor in both studies, there was very little overlap, with the somatic factor containing cognitive items such as sadness and pessimism in Mahmud’s study and affective items such as crying, agitation, and indecisiveness in Bos’ study. Neither study used CFA procedures to examine the validity of these factor solutions among postpartum women or examined the relative contributions of these factors to total BDI-II scores.

The disparate solutions produced by studies on postpartum and non-postpartum samples make it clear that factorial structure of BDI-II may be population-specific and that we need to further understand the factor structure of the BDI-II in the postpartum period. Here we use a large sample and a 2-step factor analytic procedure to generate factors to better understand dimensions of depressive symptoms among postpartum women. We first conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in half the sample and validate it on the other half by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We also examine the adequacy of our factor structure in comparison to existing factor structures of BDI-II.

Clinical utility of BDI-II factors for clinically depressed women

The clinical utility of BDI-II in postpartum women has been questioned, given the possible confounding of somatic symptoms of depression with normative physiological changes of parturition. Raising the cut-off scores based on this premise has not proven to be a useful solution for optimizing sensitivity and specificity of the measure (Chaudron et al., 2010). No studies have compared symptom endorsement and factor scores of BDI-II in postpartum depressed and nondepressed samples. Use of the BDI presents mixed results. O’Hara et al. (1990) showed that depressed childbearing women had higher somatic scores at 3 weeks postpartum compared to a matched group of depressed nonchildbearing women. Contrary to this, Whiffen and Gotlib (1993) showed that depressed women at 1 month postpartum had lower anxiety, insomnia, psychomotor agitation and somatic concerns compared to depressed nonpostpartum, after controlling for demographic characteristics. The only study to compare clinically depressed and nondepressed postpartum women on BDI items or factors (Hopkins et al., 1989) reported no differences between depressed and nondepressed women on any BDI items at 6 weeks postpartum.

Given equivocal findings regarding the relative contribution of BDI or BDI-II factors in differentiating clinically depressed and nondepressed postpartum women, we undertook an extensive investigation of the BDI-II factor structure and its relation to clinical diagnoses in postpartum. We select a sample of high-scorers, women who scored > 12, a cut-off that has shown to yield a high sensitivity and specificity rate across samples (Dozois et al., 1998) and assess whether factor scores can differentiate between depressed and nondepressed mothers as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First et al., 2001). We also examine whether factor scores can differentiate groups defined by other aspects of depression, such as presence/absence of past depression, type of depression (minor or major), and comorbidity with anxiety. Examining the relative contribution of factor scores in differentiating these groups begins to address the heterogeneity within the group of postpartum depressed women and, more broadly, advances our understanding of the clinical diagnosis of depression.

Method

Participants

Mothers who were ≥20 years of age and could read and speak English were recruited through mass mailings, women’s groups, and newspaper advertisements from a large East coast metropolitan area. The sample consisted of 953 mothers (with 543 boys and 410 girls) who filled out the BDI-II by 20 weeks postpartum and had no missing data, mothers’ M age = 31.82 (SD=5.09). All infants were full-term, healthy, singleton, M age=14.08 weeks (SD=3.31).

The psychiatric interview was conducted on a subsample of 516 mothers. Based on their zip codes, we estimated: median family income at $58,043 and ethnic distribution of 62.5% non-Hispanic White, 26.7% non-Hispanic Black, 5.7% Asian, and 5.1% Hispanic. For the subsample that was interviewed, the median family income was $95,000; 21% had partial college or less, 31% had completed college, and 48% had completed university graduate programs; 93% were married or living with someone as if married; 62% were primiparous.

Measures

The BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996) is a revised 21-item test with four response options per item that range from absence of that symptom (0) to severe or persistent expression of that symptom (3) in past 2 weeks. Each item is representative of a particular symptom of depression and corresponds to diagnostic criteria listed in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Total score is categorized as minimal depression (0–13), mild depression (14–19), moderate depression (20–28), or severe depression (29–63). Estimates of internal consistency reliability (coefficient α) have ranged from 0.88 to 0.94 for clinical and nonclinical adults (Arnau, et al., 2001; Beck et al., 1996; Seignourel, et al., 2008). In our data, the internal consistency reliability was estimated to be 0.91 for the general sample (N=953).

The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First et al., 2001) is a semi structured interview used to assign major DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses. In our study, the definition of ‘current’ episode of major or minor depression in the interview was changed from 2 months to ‘within the lifetime of the child’, as that was the question of interest.

Procedure

The BDI-II was mailed to 1131 mothers between 4 and 16 weeks postpartum, and 986 mothers (87.18%) returned the questionnaire. Of these, 33 (3.35%) were excluded because of incomplete BDI-II, mothers’ age > 45 years, and infants’ age > 20 weeks, resulting in a sample size of 953. Informed consent was obtained according to IRB procedures.

To maximize the probability of being selected into depressed and nondepressed groups, mothers who had low (1–7) and high (> 12) BDI-II scores were invited to be interviewed with the SCID-I. Of the 389 women with low scores, 269 (69.15%) were contacted and consented to the SCID interview. Of the 299 women with high scores, 236 (78.92%) were contacted and consented to the SCID interview. Participants were interviewed between 3 and 5 months postpartum by trained mental health professionals proficient with the DSM-IV classification and diagnostic criteria. Mothers who had a clinically significant depressive episode (major depression (MDD) or minor depression (mDD)) in the 5-month lifetime of their infants were classified as Depressed. Mothers without any major psychiatric diagnoses were classified as Nondepressed. Women who were diagnosed with other Axis I disorders or presented psychotic or manic symptoms were excluded. Of the low scorers on the BDI-II who underwent the SCID interview (n=269), 263 (97.77%) were classified as Nondepressed, 2 (0.74%) were diagnosed with MDD, 2 (0.74%) were diagnosed with mDD, and 2 (0.74%) with Other Axis I disorders. Of the high scorers on the BDI-II who underwent the SCID interview (n=236), 124 (52.54%) were classified as Nondepressed, 73 (30.93%) were diagnosed with MDD, 30 (12.71%) were diagnosed with mDD, and 9 (3.8%) with Other Axis I disorders.

Data Analytic Plan

Data were analyzed in five stages: 1) We conducted EFA with half of the sample using maximum likelihood (ML) extraction with oblique rotation using structural equation modeling statistics package AMOS 6.0 (Arbuckle, 2005). 2) We confirmed the fit of the generated factor structure in the second half of the sample by conducting CFA. 3) We compared our factor structure to existing factor structures of BDI-II by conducting a series of model comparisons using maximum likelihood solution and nested chi-square tests. 4) To examine the relative contribution of the factors to BDI-II total scores, we conducted GLM repeated-measures analyses. 5) To assess whether the factors differentiate clinical diagnosis and other aspects of depression (past depression, minor or major depression, and comorbidity with anxiety), we selected women who scored above the BDI-II cut-off (> 12) and conducted logistic regression analyses with the Depressed group (those diagnosed with MDD, n=73) and the Nondepressed group (n=124).

Results

The mean BDI-II score in the sample of postpartum women was 10.87 (SD = 8.37), indicating minimal depressive symptomatology. The mean BDI-II score in Depressed women (n=73) was 25.64 (SD = 8.58), indicating moderate symptoms.

Table 2 shows that somatic items were more frequently rated than cognitive and affective items, although the item-total correlations varied from low (“loss of interest in sex”, “changes in sleeping pattern”) to high (“irritability”, “concentration difficulty”). “Changes in sleeping pattern” was the most frequently endorsed symptom (90.3%), and “suicidality” was the least endorsed item (7.0%). Affective items showed high item-total correlations, whereas cognitive items varied from low (“guilty feelings” and “suicidality”) to high (“self-dislike”, “worthlessness”).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and Corrected Item-Total Correlation for each BDI-II item for the entire sample (N=953).

| Item # | Symptom | M | SD | % symptomatic | rtot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sadness | 0.19 | 0.45 | 17.30 | 0.65 |

| 2 | Pessimism | 0.27 | 0.53 | 23.90 | 0.62 |

| 3 | Past Failure | 0.34 | 0.64 | 25.00 | 0.58 |

| 4 | Loss of pleasure | 0.38 | 0.61 | 32.10 | 0.68 |

| 5 | Guilty feelings | 0.46 | 0.75 | 34.20 | 0.37 |

| 6 | Punishment feelings | 0.19 | 0.64 | 10.40 | 0.50 |

| 7 | Self-dislike | 0.43 | 0.73 | 30.20 | 0.65 |

| 8 | Self-criticalness | 0.47 | 0.72 | 36.10 | 0.61 |

| 9 | Suicidal thoughts or wishes | 0.08 | 0.29 | 7.00 | 0.39 |

| 10 | Crying | 0.47 | 0.74 | 36.40 | 0.56 |

| 11 | Agitation | 0.45 | 0.67 | 37.10 | 0.55 |

| 12 | Loss of interest | 0.40 | 0.66 | 33.10 | 0.64 |

| 13 | Indecisiveness | 0.42 | 0.67 | 32.90 | 0.65 |

| 14 | Worthlessness | 0.19 | 0.51 | 14.50 | 0.61 |

| 15 | Loss of energy | 0.79 | 0.72 | 64.40 | 0.43 |

| 16 | Changes in sleeping pattern | 1.28 | 0.67 | 90.30 | 0.40 |

| 17 | Irritability | 0.63 | 0.71 | 51.30 | 0.65 |

| 18 | Changes in appetite | 0.84 | 0.81 | 63.40 | 0.47 |

| 19 | Concentration difficulty | 0.71 | 0.72 | 56.50 | 0.62 |

| 20 | Tiredness or fatigue | 0.83 | 0.70 | 67.10 | 0.60 |

| 21 | Loss of interest in sex | 1.05 | 0.93 | 67.50 | 0.38 |

Exploratory Factor Analysis: Sample 1

The initial sample of 953 participants was randomly divided into two groups. Sample 1 (N=478) was used to generate the factor structures, and Sample 2 (N=475) was used to cross-validate the results. No statistically significant differences were found between Samples 1 and 2 on mother’s age, infant’s age, or BDI-II total scores, ts (951) < 1.64, ns.

Using the data from Sample 1, we factor analyzed the 21 items of the BDI-II using maximum likelihood extraction methods with a varimax rotation (Byrne et al. 1995, 2004). Taking into account the range of factor structures reported in the literature, we conducted EFA for potential 2-through 4-factor solutions. Only the first three eigenvalues were > 1. We used a value of .35 as a viable cutoff point for judging the saliency of factor loadings (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor Loadings for the BDI-II for Sample 1 (n=478)

| Loading | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |

| 1 | Sadness | .21 | −.19 | .71 |

| 2 | Pessimism | .46 | −.06 | .27 |

| 3 | Past failure | .77 | −.02 | −.06 |

| 4 | Loss of pleasure | .12 | .04 | .61 |

| 5 | Guilty feelings | .35 | .18 | −.10 |

| 6 | Punishment feelings | .65 | −.12 | .04 |

| 7 | Self-dislike | .60 | .12 | .08 |

| 8 | Self-criticalness | .48 | .18 | .14 |

| 9 | Suicidal thoughts or wishes | .35 | −.22 | .34 |

| 10 | Crying | .19 | .19 | .31 |

| 11 | Agitation | −.20 | .20 | .58 |

| 12 | Loss of interest | .07 | .18 | .49 |

| 13 | Indecisiveness | .10 | .28 | .40 |

| 14 | Worthlessness | .57 | .14 | −.01 |

| 15 | Loss of energy | .03 | .58 | −.13 |

| 16 | Changes in sleeping pattern | −.14 | .47 | .17 |

| 17 | Irritability | .14 | .39 | .27 |

| 18 | Changes in appetite | .22 | .44 | −.10 |

| 19 | Concentration difficulty | .03 | .48 | .23 |

| 20 | Tiredness or fatigue | −.13 | .77 | .06 |

| 21 | Loss of interest in sex | .10 | .42 | −.09 |

Note. Items loading greater than or equal to .35 are in bold.

F1=Cognitive, F2=Somatic, F3=Affective factor.

Factor 1 (eigenvalue = 7.72; % variance = 36.77) contained items such as past failures, suicidal thoughts, punishment feelings, worthlessness, self-dislike, and self-criticalness, and was labeled Cognitive. Factor 2 (eigenvalue = 1.53; % variance = 7.29) contained Somatic items such as tiredness or fatigue, concentration difficulty, loss of energy, irritability, changes in sleeping patterns, changes in appetite, and loss of interest in sex. Factor 3 (eigenvalue = 1.06, % variance = 5.03) contained Affective items such as sadness, loss of pleasure, agitation, loss of interest, pessimism, and indecisiveness. One item, crying, did not load adequately onto any of the factors and was correlated similarly with all three factors. The cumulative variance explained by the three factors was 49.09%. The correlation between Factors 1 and 2 was .58, the correlation between Factors 1 and 3 was .73, and the correlation between Factors 2 and 3 was .72.

Confirmatory Factor analysis: Sample 2

We used the maximum-likelihood estimation procedure in AMOS 6.0 to perform CFA on the covariance structures between the 21 BDI-II items. In all the models, 1) the factors were allowed to be correlated, 2) each observed variable loaded on only one factor, 3) the latent factor was scaled by using one of the observed variables as the reference indicator (i.e., by assigning a value of 1 to the regression path), and 4) all measurement errors were uncorrelated. In order not to overfit the model to the present sample, we did not do any post hoc model fitting by correlating error terms or cross-loading on the factors.

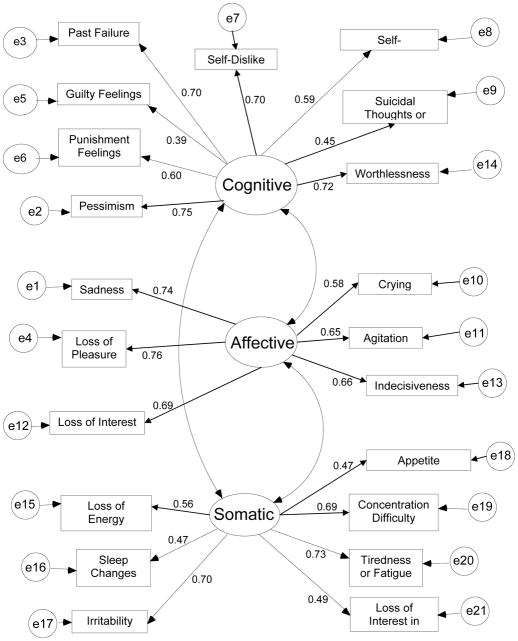

Maximum-likelihood CFA was used to confirm the adequacy of the 3-factor solution identified in the exploratory factor analysis. The final model had an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (186) = 426.80, CFI = .937, RMR = .019, RMSEA = .052 [90% CI= .046-.059], and is presented in Figure 1. All loadings were > .35. The Cognitive factor contained 8 items, Somatic factor 7 items, and Affective factor 6 items. The internal consistency reliability estimate (Cronbach’s α) was .81 for Cognitive, .77 for Somatic, and .82 for Affective factor. The factor scores for the sample were 2.40, 6.09, and 2.34 for Cognitive, Somatic, and Affective, respectively. The factor score for the Depressed group was 7.41, 11.37, and 6.87 for Cognitive, Somatic, and Affective, respectively. Compared to Bedi et al.’s (2001) study on women with MDD, the Depressed women in our study had lower scores on the Cognitive factor (7.41 vs. 9.47) [t(461)=3.20, p<.05] but similar somatic and affective scores combined (18.24 vs. 20.14) [t (461)=1.09, p>.05].

Figure 1.

Final 3-factor model of the BDI-II with standardized path coefficients.

Comparisons of Factor Structures

To assess the adequacy of the factor structure in comparison to the existing factor structures of BDI-II, we evaluated the fit of previously defined first-order 1-,2-, and 3-factor structures in our CFA sample. We chose models that had included all 21 items of the BDI-II and had N > 200. Because the χ2 statistic is sensitive to sample size, we assessed the overall fit of each model using multiple fit indices, t values, modification index, and substantive meaningfulness of the model (Bollen, 1989). As shown by the consistency across all fit indices (see Table 4), the present 3-factor model (Figure 1) provided the best fit to the observed data compared to other factor structures. Each item loaded significantly on its designated factor, providing evidence for convergent validity.

Table 4.

Fit indices for model comparisons of factor structures

| Factor Models | Study | Chisq | df | CFI | RMR | RMSEA | (90% CI) | AGFI | TLI | PCFI | BIC | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Factor | 593.36 | 189 | 0.894 | 0.024 | 0.067 | .061–.073 | 0.852 | 0.882 | 0.805 | 852.216 | 677.357 | |

| Clinical Samples | ||||||||||||

| F1:Cognitive, F2:Somatic-Affective | Becket al., 1996 | 513.35 | 188 | 0.915 | 0.022 | 0.060 | .054–.067 | 0.879 | 0.905 | 0.819 | 778.370 | 599.347 |

| F1:Cognitive, F2:Noncognitive | Steer et al., 1999 | 549.72 | 188 | 0.905 | 0.022 | 0.064 | .058–.070 | 0.867 | 0.894 | 0.810 | 814.746 | 635.724 |

| F1:Cognitive, F2:Affective, F3:Somatic | Buckley et al., 2001 | 444.42 | 186 | 0.932 | 0.020 | 0.054 | .048–.061 | 0.898 | 0.923 | 0.826 | 721.767 | 534.417 |

| Community Samples | ||||||||||||

| F1:Negative Attitude, F2:Perform, F3:Somatic | Osman et al., 1997 | 510.12 | 186 | 0.915 | 0.022 | 0.061 | .054–.067 | 0.879 | 0.904 | 0.810 | 787.473 | 600.123 |

| F1:Cognitive-Affective, F2:Somatic | Dozois et al., 1998 | 533.84 | 188 | 0.909 | 0.022 | 0.062 | .056–.069 | 0.872 | 0.899 | 0.814 | 798.860 | 619.838 |

| F1:Cognitive, F2:Somatic | Whisman et al., 2000 | 514.05 | 188 | 0.914 | 0.023 | 0.060 | .054–.067 | 0.877 | 0.904 | 0.819 | 779.074 | 600.052 |

| F1:Cognitive-Affective, F2:Somatic | Arnau et al., 2001 | 458.69 | 188 | 0.929 | 0.020 | 0.055 | .049–.062 | 0.897 | 0.921 | 0.832 | 723.717 | 544.694 |

| Postpartum Samples | ||||||||||||

| F1:Cognitive, F2:Somatic, F3:Affective | Mahmud et al., 2004 | 572.99 | 186 | 0.898 | 0.023 | 0.066 | .050–.072 | 0.857 | 0.885 | 0.796 | 850.339 | 662.990 |

| F1:Cognitive-Affective, F2:Somatic-Anxiety, F3:Guilt | Bos et al., 2009 | 477.02 | 186 | 0.924 | 0.021 | 0.057 | .051–.064 | 0.887 | 0.914 | 0.818 | 754.367 | 567.018 |

| F1:Cognitive, F2:Somatic, F3:Affective | Present Study | 426.80 | 186 | 0.937 | 0.019 | 0.052 | .046–.059 | 0.905 | 0.929 | 0.830 | 704.149 | 516.800 |

Contribution of Factor Scores to BDI-II Total

To assess the relative contribution of factor scores to high BDI-II scores, we tridivided the sample into low scorers (total score = 1–7, n=407), middle (total score = 8–12, n=247), and high scorers (total score > 12, n=299) and conducted a GLM repeated-measures analysis with the standardized factor scores as the within-subject factor and BDI-II group as the between-subject factor. The within-subject effect was significant, F (4, 1900) = 18.82, p < .001. A series of within-subject contrasts indicated that the low and middle scorers had higher somatic scores relative to cognitive and affective, whereas the high scorers had greater affective scores relative to cognitive and somatic. Thus, the relative contribution of somatic scores was in the low and middle range of BDI-II total scores.

Contribution of Factor Scores to SCID Diagnosis

To examine whether BDI-II factors predict SCID-I diagnoses in the sample of high scorers, we conducted a series of binomial logistic regressions in the subsample of participants with BDI-II totals > 12. For each analysis, SCID-I group membership was dichotomized, with the first group as the reference, and regressed on the three factors using Wald’s backward elimination. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of logistic regression for SCID diagnoses on the BDI-II factors

| SCID diagnoses | B | SE | Wald | Sig | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | Nondepressed (n=124) vs Depressed (n=73) | ||||||

| F1: Cognitive | 0.76 | 0.45 | 2.90 | p=.089 | 2.14 | 0.89, 5.13 | |

| F2: Somatic | 1.62 | 0.51 | 10.10 | p=.001 | 5.05 | 1.86, 13.72 | |

| F3: Affective | 1.70 | 0.51 | 11.24 | p<.001 | 5.45 | 2.02, 14.70 | |

|

| |||||||

| 2 | Never Depressed (N=63) vs. Depressed (N=73) | ||||||

| F1: Cognitive | 1.22 | 0.57 | 4.66 | p=.031 | 3.40 | 1.12, 10.32 | |

| F2: Somatic | 1.46 | 0.60 | 5.88 | p=.015 | 4.32 | 1.32, 14.11 | |

| F3: Affective | 1.11 | 0.57 | 3.80 | p=.050 | 3.02 | 1.10, 9.20 | |

|

| |||||||

| 3 | mDD (n=30) vs. MDD (n=73) | ||||||

| F1: Cognitive | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.98 | p=.323 | 1.81 | 0.56, 5.87 | |

| F2: Somatic | 2.71 | 0.96 | 9.48 | p<.001 | 14.99 | 3.89, 57.81 | |

| F3: Affective | −0.11 | 0.69 | 0.03 | p=.330 | 1.89 | 0.23, 3.47 | |

|

| |||||||

| 4 | Depressed only (n=51) vs. Depressed + Anxiety (n=22) | ||||||

| F1: Cognitive | 0.57 | 0.52 | 1.21 | p=.270 | 1.77 | 0.64, 4.86 | |

| F2: Somatic | 1.18 | 0.54 | 4.69 | p=.033 | 3.24 | 1.12, 9.42 | |

| F3: Affective | −0.89 | 0.61 | 2.24 | p=.134 | 0.41 | 0.13, 1.32 | |

For the first analysis, the dichotomous dependent variable was the diagnosis of current Depression, with the two groups of Not Depressed (n=124) vs. Depressed (MDD, n=73). The Not Depressed group consisted of women who were not currently depressed, but contained a subset of 61 women who had been previously depressed. Results showed that only somatic and affective factors differentiated these two groups (Wald χ2 = 10.10, p = .001, and 11.34, p < .001, respectively) with odds-ratios (OR) of 5.05 and 5.45, respectively. The Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic was 5.39 (df = 8, p = .71), indicating that the logistic model fit the data adequately; the percentage correct classification was 70%.

For the next analysis, we selected the subset of women who were not currently depressed and did not have any previous episodes of depression (Never Depressed, n=63) and compared them to the group of Depressed women (n=73). All three factors differentiated these two groups significantly with ORs of 3.40, 4.32, and 3.02 for Cognitive, Somatic, and Affective factors, respectively. For the next logistic regression with type of diagnosis (MDD vs. mDD) as the dependent variable, only the Somatic factor was significant (Wald χ2 = 9.48, p < .001). Increase in Somatic factor scores was associated with a 14.99 times increase in the odds of diagnosing MDD as opposed to mDD. Last, we examined whether the factors could differentiate between Depressed women with and without a comorbid Anxiety disorder (excluding Phobia). Only the somatic factor differentiated these two groups significantly (Wald χ2 = 4.69, p = .033). Somatic scores uniquely contributed to increased odds of having a comorbid Anxiety diagnosis by a factor of 3.24 as opposed to Depression alone.

Discussion

Results of the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of 21 BDI-II items in a large sample of postpartum women revealed that a 3-factor solution comprised of cognitive, affective, and somatic domains best represented the underlying dimensions of depressive symptoms. When depressive symptoms are measured with the BDI-II in postpartum women, cognitive and affective symptoms form distinct clusters separate from somatic symptoms of depression. Based on rigorous model comparisons using multiple fit indices, our 3-factor model provided the most parsimonious fit to the data compared to previously defined first-order 1-, 2-, and 3-factor structures. The three correlated domains showed high internal consistency, supporting the reliability of derived factor scores, and accounted for 50% of the variance, which was comparable to other studies (see Table 1).

Factor Structure of BDI-II

The cognitive cluster was characterized by items such as self-dislike and worthlessness that reflect negative views of self, as well as the items such as past-failure and pessimism that reflect global negative views. The finding that the Cognitive factor accounted for most of the common variance (36%) among women’s responses indicates that depression severity is characterized more by the cognitive symptoms than by affective or somatic symptoms. This result is similar to studies of non-postpartum samples (Dozois et al., 1998; Kneipp, et al., 2009; Osman et al., 2004) but contrasts with other studies of postpartum women using the BDI-II (Bos et al., 2009; Mahmud et al., 2004) wherein the variance was similar across cognitive, somatic, and affective factors. One possible explanation may be cross-cultural differences in depressive symptoms, given that the previous studies were conducted with Portuguese and Malaysian samples.

Somatic items clustered into a separate factor, the item composition of which was similar to other studies of psychiatric as well as nonclinical samples. With the exception of two items (“loss of interest in sex” and “changes in sleep”) that had low item-total correlation, somatic items correlated as highly with the total BDI-II score as any other BDI-II items. The somatic factor accounted for less variance in our study than in other studies with postpartum samples (Bos et al., 2009; Mahmud et al., 2004) but had the highest factor mean, signifying that women in our sample reported more somatic symptoms relative to cognitive or affective symptoms, a pattern that is suggestive of the normative postpartum adjustment. Results of GLM repeated-measures analysis showed that the relative contribution of somatic scores was in the low and middle range of BDI-II total scores, a finding similar to the results of Salamero et al., (1994) on pregnant women that used the older version of BDI. Women with high BDI-II total scores tended to endorse somatic items only if they endorsed cognitive and affective items as well, suggesting that somatic items covary with the cognitive and affective items in the higher range. Somatic items are thus required to provide an optimal explanation of the overall depression construct and severity of depression symptomatology.

The emergence of an affective cluster as a separate factor in our study was unique, given that only two other studies had an affective factor in their solution (Buckley et al., 2001; Mahmud et al., 2004). Affective items are known to load on different dimensions depending on the type of sample being studied (Beck et al., 1996). Although the affective factor accounted for only 5% of the variance in our study, it was comprised of items central to depressed mood – items related to dysphoria, such as sadness, loss of pleasure, and loss of interest, as well as items related to distress, such as crying, agitation, and indecisiveness.

The severity of depressive symptomatology endorsed by postpartum Depressed women in our study was significantly less than that of depressed women in Bedi et al. (2001) and Steer et al. (1999). In addition, when comparing factor scores, Depressed women in our study scored lower on cognitive factor, but did not differ on somatic and affective factor scores compared to depressed women in Bedi et al.’s study (2001). These results provide tentative empirical support for the notion that depression in postpartum women might be less severe and not characterized by a depreciating view of self, key symptoms among psychiatric patients. This is similar to the findings from studies of medically ill patients that show that depressed patients with chronic pain do not exhibit the cognitive biases shown by depressed patients without chronic pain (Morley et al., 2002).

Factor Scores and Clinical Diagnosis

We investigated the specificity of BDI-II factor scores by conducting binomial logistic regressions on groups based on SCID diagnoses in a subsample of women whose total BDI-II scores were > 12. When we compared women with a diagnosis of major depression and women who were not currently depressed, the Depressed women had higher somatic and affective factor scores, but similar cognitive factor scores compared to Nondepressed women. For women who scored high on the BDI-II, those who endorsed more affective and somatic items were more likely to be clinically depressed.

Because prior depressive episodes predict postpartum depression (Viguera et al., 2011), and influence symptom clustering (Huffman et al., 1990), we selected a subgroup of women who were not currently depressed and were not previously depressed (Never Depressed) to compare to Depressed women on the factor scores. For this comparison, all three factor scores distinguished the groups – Depressed women endorsed higher cognitive, affective, and somatic symptoms than women who were never depressed. Taken together with the first group comparison, these results show that women who were previously depressed endorsed more cognitive symptoms on the BDI-II, or, conversely, that the cognitive dimension of the BDI-II is sensitive to prior episodes of depression. This finding clarifies and lends support to Huffman et al. (1990) who reported that the cognitive factor discriminated women with and without past depressive episodes.

Women with major depression endorsed more somatic symptoms compared to women with minor depression, but there were no differences in relative endorsement of cognitive or affective symptoms. It is possible that women who endorse somatic items in addition to cognitive and affective items on the BDI-II experience a more severe form of depression that impacts their daily functioning in several areas, leading to a diagnosis of MDD rather than mDD. This interpretation suggests that women with subclinical, or minor, depression experience similar levels of cognitive impairment, dysphoria, and subjective distress to women with major depression, a finding that has been observed in studies with postpartum women (Weinberg et al., 2001).

Given the overlap between depression and anxiety (Sloan et al., 2002) and their frequent co-occurrence in postpartum women (Stuart et al., 1998), we compared Depressed women with a diagnosis of anxiety to Depressed women without comorbid anxiety. Only the somatic factor differentiated these two groups; Depressed women with comorbid anxiety endorsed more somatic symptoms than Depressed women without an anxiety diagnosis. These results suggest that impairment in physical functioning and performance difficulties due to fatigue, changes in sleep and appetite, concentration difficulties, irritability, and loss of interest in sex are indicative of anxiety in women who are already depressed. Our finding lends support to the somatic-anxiety factor found in Bos et al. (2009), wherein most of their constituent items overlapped with our somatic factor. Although anxiety has been shown to be a prominent feature of depression during postpartum (Stuart et al., 1998), to our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the expression of anxiety as somatic symptoms in postpartum depressed women.

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted with the caution in that our definition of clinical depression included episodes of depression during the child’s lifetime, and depressive symptoms were not necessarily current at the time of the assessment. Although we think this would not impact the factor structure, it is conceivable that a change in definition might affect the relative contributions of the three factors in distinguishing depressed and nondepressed women. Another limitation of this study is that we only examined the specificity of factor scores for women who scored high on the BDI-II. We did not examine clinical utility in the low scorers, as to whether the somatic, affective, and cognitive dimensions in low scorers suggest absence of depression. While this was not possible in the current study, given the low incidence of depression among the low scorers and the limited variability in factor scores at the low end, it is important for future research to investigate this question by using other methodology.

Conclusion

Depressive symptomatology during the postpartum period can be delineated into three dimensions of cognitive, somatic, and affective symptoms using the BDI-II. Endorsement of cognitive items contributes most to depression severity, and all three dimensions contribute to clinical diagnosis. Despite the relatively high endorsement of somatic items in this study, results support the inclusion of somatic symptoms of depression in the calculation of a BDI-II total score.

Somatic symptoms contribute to the identification of depression and are associated with a greater probability of being diagnosed with major depression, and depression with comorbid anxiety. Although somatic symptoms of depression may be difficult to differentiate from the physiological changes of normative postpartum adjustment, the findings of the present study suggest that it is too early to abandon the use of somatic items for detecting depression in the postpartum period. Rather, further research is needed to better understand the relation of somatic and other dimensions to depression symptomatology, severity, and functioning.

Conceptualizing the structure of the BDI-II using these three factors could contribute to refining the measurement and scoring of depressive symptomatology and severity in postpartum women. Delineation of dimensions of depressive symptoms may also help to ascertain possible differential responses to treatments (e.g., cognitive therapy, medication) and to monitor changes over the postpartum period. It would also be informative to examine, differential relations between factorial dimensions of depressive symptomatology and maternal functioning.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, NIH.

We thank the parents and children who gave their time and effort to participate in this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributors: Author Nanmathi Manian co-designed the larger study, originated the paper, conducted statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Elizabeth Schmidt conducted literature searchers, helped with data analyses, and revised the manuscript. Marc Bornstein co-designed the larger study and made revisions to the manuscript. Pedro Martinez revised the manuscript and provided clinical expertise. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 6.0 [Computer software] AMOS Development Corporation; Springhouse, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol. 2001;20:112–119. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corp; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi RP, Koopman RF, Thompson JM. The dimensionality of the Beck Depression Inventory-II and its relevance for tailoring the psychological treatment of women with depression. Psychother. 2001;38:306–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 1989;17:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Bos SC, Pereira AT, Marques M, Maia B, Soares MJ, Valente J, Gomes A, Macedo A, Azevedo MH. The BDI-II factor structure in pregnancy and postpartum: Two or three factors? Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RC, Le HN, Somberg R. Review of screening instruments for postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TC, Parker JD, Heggie J. A psychometric evaluation of the BDI-II in treatment–seeking substance abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Baron P, Larsson B, Melin L. The Beck Depression Inventory: Testing and cross-validating a second-order factorial structure for Swedish nonclinical adolescents. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0050-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Stewart SM, Lee PWH. Validating the Beck Depression Inventory-II for Hong Kong community adolescents. Int J Testing. 2004;4:199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody DP. Psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with college students of diverse ethnicity. Int J Psychiatry Clin Prac. 2005;9:22–28. doi: 10.1080/13651500510014800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Tang W, Anson E, Talbot NL, Wadkins HI, Tu X, Wisner KL. Accuracy of depression screening tools for identifying postpartum depression among urban mothers. Pediatrics. 2010;125:609–617. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. SCID-I-TR: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Disorders. Biometrics Research; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harris CA, D’Eon JL. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-(BDI-II) in individuals with chronic pain. Pain. 2008;137:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B, Huckle P, Thomas R, Johns S, Fung H. The use of rating scales to identify post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:813–817. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins J, Campbell SB, Marcus M. Postpartum depression and postpartum adaptation: Overlapping constructs? J Affect Disord. 1989;17:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(89)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman LC, Lamour M, Bryan YE, Pederson FA. Depressive symptomatology during pregnancy and the postpartum period: Is the Beck Depression Inventory applicable? J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp SM, Kairalla JA, Stacciarini J, Pereira D. The Beck Depression Inventory II factor structure among low-income women. Nurs Res. 2009;58:400–409. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181bee5aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DT, Yip AS, Chiu HF, Leung TY, Chung TK. Screening for postnatal depression: Are specific instruments mandatory? J Affect Disord. 2001;63:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud WMRW, Awang A, Herman I, Mohamed MN. Analysis of the psychometric properties of the Malay version of Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) among postpartum women in Kedah, North West of Peninsular Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2004;11:19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley S, Williams AC, de C, Black S. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory in chronic pain. Pain. 2002;99:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Zekowski EM, Philipps LH, Wright EJ. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: Comparison of childbearing and nonchildbearing women. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:3–15. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Downs WR, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, Gutierrez PM, Chiros CE. Factor structure and psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1997;19:359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Kopper BA, Barrios F, Gutierrez PM, Bagge CL. Reliability and validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Psychol Assess. 2004;16:120–132. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson AL, Morasco BJ, Fuller BE, Indest DW, Loftis JM, Hauser P. Screening for depression in patients with hepatitis C using the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Do somatic symptoms compromise validity? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole H, Bramwell R, Murphy P. Factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:790–798. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210930.20322.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamero M, Marcos T, Gutierrez F, Rebull E. Factorial study of the BDI in pregnant women. Psychol Med. 1994;24:1031–1035. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700029111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seignourel PJ, Green C, Schmitz JM. Factor structure and diagnostic efficiency of the BDI-II in treatment-seeking substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP, Bradley MM, Strauss CC, Lang PJ, Cuthbert BC. Examining high-end specificity of the Beck Depression Inventory using an anxiety sample. Cogn Ther Res. 2002;26:719–727. [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Dimensions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in clinically depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55:117–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199901)55:1<117::aid-jclp12>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Clark DA. Psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with college students. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 1997;30:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Kumar G, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with adolescent psychiatric outpatients. J Psychopathol Beh Assess. 1998;20:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Roberti JW, Roth DA. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition in a sample of college students. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19:187–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, O’Hara MW, Gorman L. Postpartum anxiety and depression: Onset and comorbidity in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:420–424. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon SD, Cluxton-Keller F, Leis J, Le H-N, Perry DF. A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low-income African American women. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguera AC, Tondo L, Koukopoulos AE, Reginaldi D, Lepri B, Baldessarini RJ. Episodes of mood disorders in 2,252 pregnancies and postpartum periods. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1179–1185. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ, Beeghly M, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley JM. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in postpartum women. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:87–97. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE, Gotlib IH. Comparison of postpartum and nonpostpartum depression: Clinical presentation, psychiatric history, and psychosocial functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:485–494. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Perez JE, Ramel W. Factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory – Second Edition (BDI-II) in a student sample. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:545–551. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<545::aid-jclp7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]