Abstract

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process through which different components of the cells are sequestered into double-membrane cytosolic vesicles called autophagosomes, and fated to degradation through fusion with lysosomes. Autophagy plays a major function in many physiological processes including response to different stress factors, energy homeostasis, elimination of cellular organelles and tissue remodeling during development. Consequently, autophagy is strictly controlled and post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination have long been associated with autophagy regulation. In contrast, the importance of acetylation in autophagy control has only emerged in the last few years. In this review, we summarize how previously identified histone acetylases and deacetylases modify key autophagic effector proteins, and discuss how this has an impact on physiological and pathological cellular processes.

Keywords: ATG genes, FOXO, Huntington disease, acetylation, autophagy, deacetylation, lysine, post-translational modification, protein aggregates

Introduction

Autophagy was initially described as a lysosome-dependent degradation of cytoplasmic components following starvation, maintaining intracellular energy homeostasis when external resources are limited.1 In the past 10 to 15 years, autophagy has been associated with multiple physiological processes including the response to different extracellular or intracellular stress factors such as starvation, growth factor deprivation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, elimination of damaged organelles, protein aggregates or long-lived proteins, and cellular and tissue remodeling during animal development.2-4 This conserved cellular process is associated with many human diseases and is important in cellular self-defense against pathogen infection.5,6

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are crucial for the regulation of eukaryotic proteins. Among the major PTMs are tyrosine or serine/threonine phosphorylation, lysine and N-terminal acetylation, lysine/arginine methylation, SUMOylation and ubiquitination. It is well known that phosphorylation events have essential roles in the initiation step of autophagy. For example, the yeast autophagy-related (Atg)1-Atg13 complex is regulated by at least two different protein kinases, TOR and PKA. Ubiquitination is also crucial for autophagy. Two major ubiquitin-like systems are involved in the elongation of the phagophore, the precursor compartment to the autophagosome. In mammals, the autophagic protein ATG12 is conjugated to ATG5 by the E2-like protein ATG10, whereas LC3 is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine by ATG3.7,8 Lysine side chains of proteins involved in autophagy control can be targeted by multiple, mutually exclusive PTMs targeting the same lysine and providing an opportunity for cross-regulation.9

In contrast to phosphorylation and ubiquitination, the importance of acetylation in autophagy control has only recently emerged. While initially identified in histones 40 years ago, lysine acetylation also affects many nonhistone proteins, including transcription factors as well as cytoplasmic proteins regulating cytoskeleton dynamics, energy metabolism and endocytosis.9,10 New studies highlight the contribution of acetylation in autophagy control. Here we summarize the emerging support for acetylation-mediated control of autophagy and discuss the implication in the context of human diseases such as Huntington disease and cancer.

HATs and HDACs Operate at Multiple Levels of the Autophagy Process

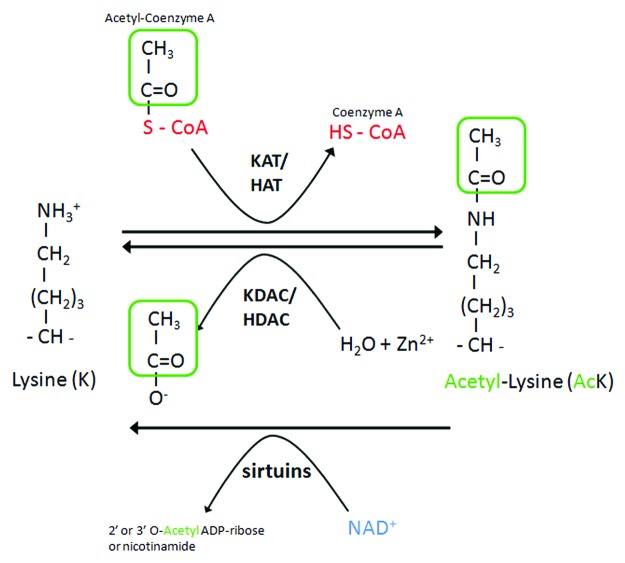

Lysine acetylation and deacetylation of proteins were first and extensively studied in histones. However, targets for histone acetylases (HATs) or histone deacetylases (HDACs) often also include nuclear nonhistones and cytoplasmic proteins.9 Lysine acetylation is catalyzed by lysine acetyltransferases (KATs), which transfer an acetyl-group of acetyl-CoA to the ɛ-amino group of an internal lysine residue. The reverse reaction is accomplished by lysine deacetylases (KDACs) (Fig. 1). KATs fall into three major classes: KAT2/GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases (GNAT family), E1A binding protein p300 (EP300/CREBBP family), and MYST family. Deacetylases are also divided into several classes. The class I, IIa, IIb, and IV enzymes are zinc-dependent, whereas the class III family comprises sirtuins, and use NAD+ as a cofactor to catalyze deacetylation reactions.11 A growing body of evidence, including HATs and HDACs gain- and loss-of-function mutants (Table 1) and the use of HDAC inhibitors (Table 2), support the idea that HATs and HDACs play a pivotal role in autophagy regulation, by acting at multiple levels. The first level regards epigenetic regulation of autophagy genes by histone acetylation. This level may explain some of the effects associated with HAT and HDAC mutations, as well as effects associated with the use of HDAC inhibitors. For example, in response to spermidine treatment, the ATG7 gene is upregulated, which is accompanied by histone hyperacetylation of the promoter region of the gene.53 This mode of acetylation-mediated control of autophagy relies on a mechanism of transcriptional regulation broadly used in genome regulation and is not specific to the control of autophagy. Modification of the acetylation status and the activity of core autophagy proteins, transcription factors regulating autophagy or cytoskelal proteins shaping the cellular context for autophagy, constitute additional levels of autophagy control that we discuss further below.

Figure 1. Acetylation control by KATs-HATs and KDACs-HDACs. Acetylation and deacetylation of proteins at lysine residues are mediated by lysine acetylases (KATs or HATs) and deacetylases (KDACs or HDACs). KATs/HATs transfer an acetyl-group of acetyl-CoA to the ɛ-amino group of an internal lysine residue. The reverse reaction is mediated by KDACs-HDACs and requires Zn2+, whereas sirtuins requires NAD+.

Table 1. Regulation of autophagy by lysine acetyltransferases (KATs), lysine deacetyltases (KDACs) and N-acetyltransferases (NATs).

| HATs | |

|---|---|

|

EP300-CREBBP family | |

| CREBBP/KAT3A |

Induction of aggrephagy12-16 |

| EP300/KAT3B |

Inhibition17 |

|

MYST family | |

| KAT5/TIP60 |

Induction18,19 |

|

HDACs | |

|

Class I | |

| HDAC1 |

Inhibition20 Inactivation induces autophagic cell death21 Induction22 Induction by controlling the expression of autophagic proteins23 |

| HDAC2 |

Induction22 Induction by controlling the expression of autophagic proteins23 |

| HDAC3 |

Inhibition through p2124 |

|

Class IIa | |

| HDAC4 |

No effect25 Inhibition through CDKN1A24 Inhibition26 |

| HDAC5 |

Inhibition26 |

| HDAC7 |

Inhibition27 |

|

Class IIb | |

| HDAC6 |

Induction through cortactin, tubulin, dynein28-31 Induction of autophagic cell death thought BECN1-MAPK/JNK32 |

|

Class III/Sirtuins | |

| SIRT1 |

Induction by deacetylation of ATGs and FOXO133,34 Induction35 |

| SIRT2 |

Foxo1 deacetylation, inhibition36 |

| SIRT3 |

Induction37 |

|

NATs | |

| NAT10 |

Induction by repressing the TSC1-TSC2 complex38,39 |

| NAT9 | Knockdown increases autophagy flux40 |

No roles in autophagy are reported for HAT1/KAT1, KAT2A, KAT2B, ELP3/KAT9 (GNAT family), KAT6A, KAT6B, KAT7, KAT8, (MYST family), HDAC8 (Class I), HDAC9 (Class IIa), HDAC10 (Class IIb), HDAC11 (Class IV), SIRT4, SIRT5, SIRT6, SIRT7 (class III/sirtuins) and NAA40/NAT11, NAA60/NAT15, NAT16, NAA20, NAA25, NAA30, NAA35, NAA38, NAA40, NAA50 (NATs).

Table 2. HDAC inhibitors and activators and their effect on autophagy.

| HDAC inhibitors | Specificity | Used model system | Effect | Targeted proteins | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SAHA |

Class I, II and IV HDACs |

Endometrial stromal cells (HESCs) and (ESS1) |

Induction of caspase-independent autophagic cell death |

HDAC7 |

27 |

| HeLa cells |

Hyperacetylation of tubulin, increased LC3-I to LC3-II conversion |

Not specified |

20 |

||

| Chondrosarcoma cell lines |

Induction of autophagic cell death |

Not specified |

41 |

||

| Mouse neuronal cells |

Induction of autophagy |

HDAC6 |

42 |

||

|

Longevinex |

|

Rat, isolated heart |

Induction of autophagy, phosphorylation of FOXOs |

SIRT1 SIRT3 |

37 |

|

FK228 |

|

HeLa cells |

Induction of autophagy increased LC3-I to LC3-II conversion |

HDAC1 |

20 |

| Malignant rhabdoid tumor cells |

Induction of autophagy by redistribution of AIFM1 to the nucleus |

Not specified |

43 |

||

|

Valproic acid (VPA) |

Class I and class IIa HDACs |

Glioma cells |

Induction of autophagy trough induction of oxidative stress pathway |

Not specified |

44 |

| Yeast |

Atg19-dependent autophagic degradation of SAE2 |

Gcn5/SAGA |

45 |

||

|

butyrate |

Class I and IIa HDACs |

Mammalian colon cells |

Induction of autophagy |

Not specified |

46 |

|

Butyrate and SAHA |

Class I-IV HDACs |

HeLa cells |

Induction of autophagic cell death |

Not specified |

47 |

|

H40 and SAHA |

HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC4 |

Prostate cancer PC-3M cells |

Autophagic cell death by upregulation of CDKN1A |

HDAC3 and HDAC4? |

48 |

|

MS-275 |

HDAC1,HDAC2 HDAC3 |

MPNST cell lines |

Induction of autophagy (MPNST survival mechanism) |

|

49 |

|

LBH589 |

HDAC4 and HDAC5 |

Waldenström macroglubulinemia lymphoma cells |

Induction of autophagy |

HDAC4 and HDAC5 |

26 |

|

Tubacin |

HDAC6 tubulin deacetylase activity |

MEF |

Autophagy inhibition |

HDAC6 |

50 |

|

Sirtinol |

SIRT1 inhibition |

Lung epithelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages |

Augmentation of cigarette smoke_induced autophagy |

SIRT1 |

51 |

|

Spermidine |

Not known |

Human colon cancer cells, yeast, C. elegans |

Induction of autophagy |

Independent of SIRT1/Sir2/sir-2.1 |

52 |

| HeLa celles, flies |

Induction of autophagy |

|

53 |

||

| Resveratrol | Sirt1 inducer |

Lung epithelial cells, fibroblasts and macrophages |

Attenuation of cigarette smoke-induced autophagy |

SIRT1 |

51 |

| Human colon cancer cells, yeast, C. elegans | Induction of autophagy | SIRT1/Sir2/sir-2.1 | 52 |

Modification of the Acetylation Status and Activity of Autophagy Core Components

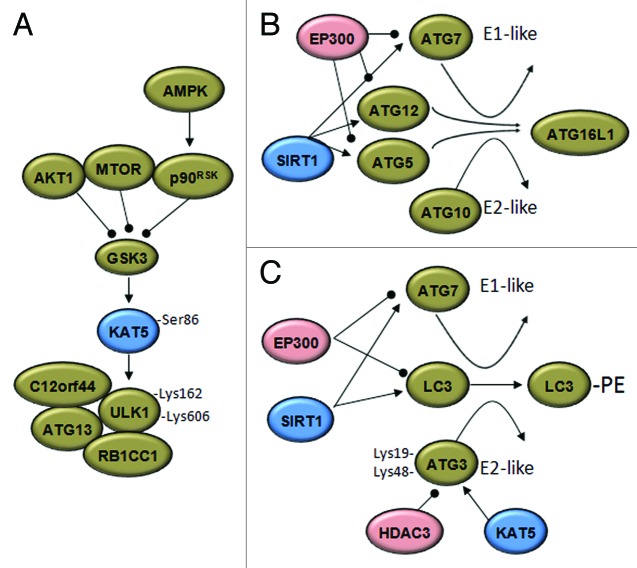

The ATG proteins provide the core molecular machinery essential for phagophore formation and elongation. They form four complexes: the kinase complex ATG1–ATG13; the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex I (containing BECN1, ATG14, PIK3C3/VPS34 and PIK3R4/VPS15) and two ubiquitin-like protein conjugation complexes (ATG12–ATG5-ATG16L1, along with ATG7 and ATG10, and LC3–PE, with ATG4, ATG7 and ATG3).54 So far, many ATG proteins have been demonstrated to be acetylated and their acetylation status is regulated by specific HAT-HDAC pairs, including EP300-sirtuins and MYST-HDAC3/RPD3 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Acetylases and deacetylases modify the autophagic machinery. (A) Under growth factor deprivation, the activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) during autophagy initiation results in phosphorylation of the KAT5 acetyltransferase, which activates the ULK1 kinase. p90RSK, RPS6K p90. (B) The EP300 acetyltransferase inhibits the elongation of the autopahosome membranes by acetylating ATG5, ATG7, ATG8 and ATG12. Under starved conditions, SIRT1 deacetylates these ATG proteins and induces autophagy. (C) Results in yeast support the idea that starvation-induced acetylation of Atg3 at K19 and K48 by Esa1 (KAT5) controls its interaction with Atg8 (LC3) and Atg8 lipidation. Deacetylation of Atg3 is accomplished by the deacetylase Rpd3 (HDAC3). Arrowheads and balls respectively indicate inducing or inhibitory effects.

MYST and HDAC3

MYST acetyltransferases are defined by a conserved histone acetyltransferase domain called MYST, which contains a C2HC zinc finger and an Ac-CoA binding domain.55 Recent papers highlight the importance of the MYST acetyltransferase family in autophagy regulation. Under growth factor deprivation, when MTOR, AKT1 and the MAP kinase pathways are repressed, the activation of GSK3 induces phosphorylation and activation of KAT5/TIP60 acetyltransferase, which in turn acetylates and activates the autophagy-initiation kinase ULK1 that is essential for serum deprivation-induced autophagy.18 In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Esa1 (the ortholog of KAT5) regulates the autophagy signaling component Atg3. Starvation-induced acetylation of K19 and K48 of Atg3 controls its interaction with Atg8 as well as the lipidation of Atg8. The reverse reaction is accomplished by the deacetylase Rpd3.19 Interestingly, the antagonistic function of the class I family member Rpd3 deacetylase and of another MYST acetyltransferase, chm/chameau, was previously reported.56,57

EP300-CREBBP and sirtuins

In mammalian cells, the EP300 acetyltransferase and ATG7 colocalize within the cytoplasm. The physical interaction of these two proteins depends on nutrient availability and results in acetylation of ATG7.17 In this instance, the NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 was shown to deacetylate ATG7, as well as other ATG proteins (ATG5, LC3 and ATG12), thereby controlling the activity of these proteins essential for autophagic vesicle formation.33 Furthermore, the use of a specific SIRT1 inducer, resveratrol, and an acetyltransferase inhibitor, spermidine, synergize in the induction of autophagy. This synergistic effect is associated with deacetylation of autophagy core components such as ATG5 and LC3.52 Extending this finding and supporting a broad use of the acetylation status as a key regulatory control of the activity of autophagic components, it was reported that resveratrol and spermidine induce changes of the acetylation status of 170 proteins whose activity is connected to autophagy control.58 Acetylation may also serve as a mechanism of fine-tuning and controlling the reversibility of the regulation by HATs and HDACs. SIRT2 controls the self-acetylation of EP300, which may also acetylate SIRT2 to inhibit its enzymatic activity.59,60

The use of acetylation for regulating the activity of autophagy core components is interesting, as it allows coupling the regulation of autophagy to the cell metabolic state. The maintenance of cellular energy homeostasis requires the intracellular storage and usage of lipids, and autophagy is proposed to play an important role in regulating intracellular lipid mobilization (macrolipophagy).61-63 In response to starvation, lipid mobilization involves β-oxidation of fatty acids in the mitochondria and leads to the production of NADH and acetyl-CoA, which is a co-enzyme required for proper activity of EP300. A possible mechanism that may link starvation and acetylation-associated autophagy induction is the increased Ac-CoA level, which negatively feeds back by inhibiting autophagy/macrolipophagy through EP300-mediated acetylation of autophagic components. In addition, the associated decreased level of NAD+/NADH can lead to the inactivation of sirtuins. Further experimental work is required to support this hypothesis.

Regulation of Autophagy through the Acetylation of FOXO Transcription Factors

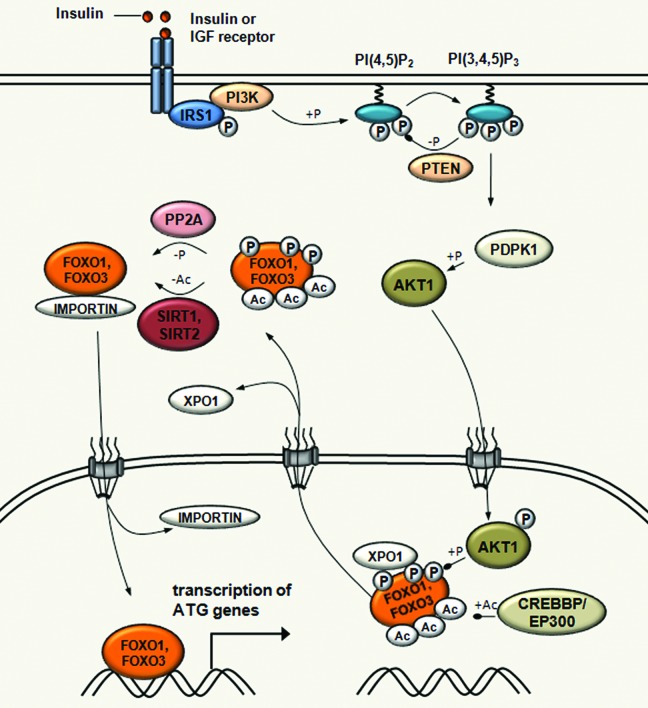

Control of autophagy though the acetylation of transcription factors is best illustrated by the FOXO family members (Fig. 3). FOXO proteins are forkhead domain-containing evolutionarily conserved transcription factors, with a unique representative in Drosophila, foxo/dFOXO and several orthologs in mammals (FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4 and FOXO6).64,65 FOXO transcription factors have been associated with a multitude of biological processes, including cell cycle, proliferation, cell death, DNA repair, metabolism, protection from oxidative stress and autophagy.66,67 For example, FOXO1 and FOXO3 have important roles in the regulation of autophagy in skeletal and cardiac muscles by activating genes that are involved in autophagosome formation, and fasting in Drosophila induces autophagy by enhancing the expression of genes downstream of foxo/dFOXO. Interestingly, similar effects were observed in muscle cells following overexpression of FOXO3.68-70 The FOXO transcription factors are targeted by multiple post-translational modifications controlling subcellular localization, DNA binding and trancriptional properties.65,71

Figure 3. Acetylation-mediated control of FOXO transcription factor activity in autophagy regulation. SIRT1 induces autophagy through the deacetylation of FOXO1 upon starvation. SIRT1 also deacetylates FOXO3, which is required for the transcriptional activation of genes that are involved in autophagosome formation, such as MAP1LC3, PIK3C3, GABARAPL1, ATG12, ATG4, BECN1, ULK1 and BNIP3. In fed conditions, EP300-CREBBP acetyltransferases increase FOXO1 and FOXO3 acetylation, which results in decreasing their DNA binding activity and in increasing their sensitivity to phosphorylation. In response to insulin, FOXO1 and FOXO3 are phosphorylated by AKT1 leading to its dissociation from DNA and subsequent export to the cytoplasm through XPO1/CRM1-mediated export.

Acetylation of FOXO1 on three lysine residues (K242, K245 and K262) is mediated by the CREBBP acetyltransferase and impairs FOXO1-mediated transcriptional regulation.72 Consistent with this, overexpression of EP300 significantly increases FOXO1 acetylation and inhibits autophagy.34 This acetylation decreases DNA binding efficiency of FOXO1 and promotes its subsequent phosphorylation by AKT1.72 Upon insulin or other growth factors signaling, and AKT1-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO1 and also FOXO3, acetylation leads to its dissociation from DNA and subsequent nucleocytoplasmic transport.73

The acetylation status of FOXO proteins is also regulated by deacetylation, which involves sirtuin deacetylases. SIRT1 controls the subcellular localization and activity of FOXO1 through the deacetylation of an LXXLL motif, which has an impact on association with the promoter, and transcription of the patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 2/adipose triglyceride lipase (PNPLA2/ATGL) gene encoding a rate-limiting lipolytic enzyme.74 PNPLA2 is a major lipase for fat mobilization from lipid droplets in mammals and in Drosophila.75,76 SIRT1 was also shown to deacetylate FOXO3, which in skeletal muscle activates genes that are involved in autophagosome formation, including MAP1LC3, PIK3C3/VPS34, GABARAPL1, ATG12, ATG4, BECN1, ULK1 and BNIP3.68,77 Similarly, SIRT2 also deacetylates FOXO1 and FOXO3 following caloric restriction.78,79 Of note, the expression of SIRT2 is upregulated in starved conditions, which emphasizes its important role in FOXO deacetylation and promoting lipid remobilization.78

In addition to influencing autophagy through the control of the expression of autophagic genes, FOXO1 also regulates autophagy in a transcription-independent manner. This was shown in the context of human cancer cells and, as in transcriptional regulation, the acetylation status controls FOXO activity: dissociation from SIRT2 in response to serum deprivation results in the acetylation of FOXO1, promoting its interaction with ATG7 and inducing the autophagic process.36 In summary, deacetylation-activated FOXO1 and FOXO3 coordinate the induction of autophagy under low-energy conditions, by contributing to autophagosome formation through transcriptional upregulation of core autophagy genes and by direct protein-protein interaction with ATG7.

Acetylation-Mediated Control of Cytoskeletal Properties/Dynamics and Autophagy Regulation

Tubulin was the first acetylated cytosolic protein described.80,81 The acetylation status of microtubules is coordinated by the HDAC682 and SIRT283 deacetylases and by the ELP3/KAT9 acetylase,84 which also regulates actin dynamics, stress signaling and exocytosis.85,86 Microtubule stability and function are regulated by the reversible acetylation of α-tubulin. A recent study showed that a dynamic microtubule subset acts in stress-induced autophagy. Upon nutrient deprivation, tubulin acetylation on Lys40 increases both in labile and stable microtubule fractions, which enhances MAPK/JNK phosphorylation and activation via KIF1/kinesin family member 1-dependent mechanisms and promotes autophagy. MAPK/JNK signaling increases the dissociation of BECN1 (Atg6) from the BCL2 inhibitor and promotes its association with factors such as microtubules required for initiating autophagosome formation. While the markers of phagophore/autophagosome formation (BECN1, class III PtdIns3K, WIPI1, ATG12–ATG5 and LC3-II) are specifically recruited on labile microtubules, mature autophagosomes (marked with LC3-II) can move along stable microtubules.87 Tubulin acetylation is also essential for fusion of autophagosomes to lysosomes.88,89

Long-distance organelle movement is performed by cellular motor proteins that deliver cargoes along the microtubule tracks. Dynein moves toward the slow growing or “minus” ends of microtubules, and is responsible for centripetal transport, while centrifugal movements are driven by kinesins. Tubulin acetylation at Lys40 increases the recruitment and mobility of KIF1 and dynein in vitro and in vivo.42,90 A number of studies reveal that after formation, autophagosomes are centripetally delivered by dyneins along the microtubule tracks in the direction of the centrosomes where lysosomes are usually concentrated.87,91-93 The dynein motor machinery also plays a role in autophagosome-lysosome fusion.94 As a consequence, mutations that influence the dynein motor machinery reduce the efficiency of autophagic clearance of protein aggregates and increase levels of LC3-II.91 KIF1 is involved in autophagosome traffic in basal nutrional conditions. In contrast with its increased recruitment on microtubules to activate MAPK/JNK (see above), KIF1 is no longer involved in motoring autophagosomes upon nutrient deprivation. In parallel, dynein participates in motoring autophagosomes both in basal and in starved conditions.87 These data collectively establish the importance of tubulin acetylation in autophagy dynamics. Further work is required, however, to demonstrate direct links between HDAC6, SIRT2 and ELP3 activity, and acetylated tubulin-controlled autophagy induction.

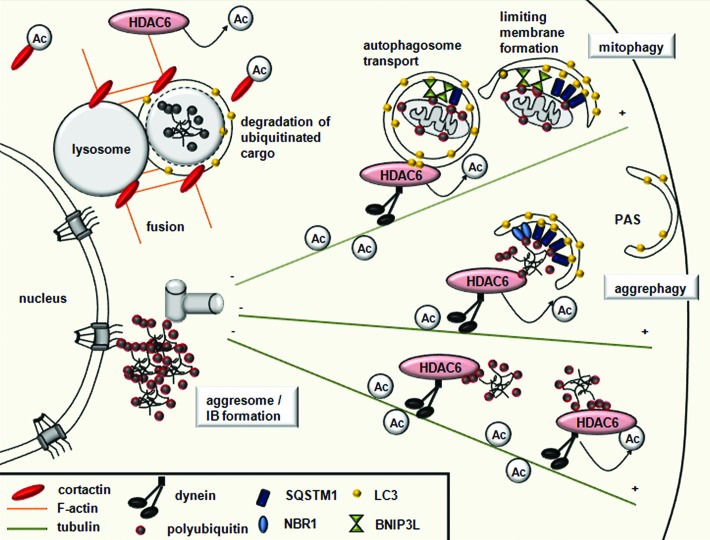

HDAC6, Actin and Selective Autophagy

Similarly to tubulin, cytoskeletal actin is also targeted by acetylation. HDAC6 has emerged as a central regulator of selective types of autophagy, which exclusively eliminates specific cellular components (Fig. 4).50,95,96 A recent study suggests that this specific form of autophagy, termed quality control (QC) autophagy, triggers intracellular quality control by selectively disassembling altered, nonfunctioning organelles and protein aggregates.29

Figure 4. HDAC6 controls selective autophagy by recruiting the actin and tubulin networks. Ubiquitinated substrates are specifically bound by the UBA domain of autophagy receptors SQSTM1/p62 and NBR1, while damaged mitochondria are specifically recognized by BNIP3L/NIX receptors. All autophagy receptors have a LIR domain, which recruits the membrane to the cargo by binding LC3. HDAC6 recruits cortactin to the ubiquitinated protein aggregates or mitochondria, and, through cortactin deacetylation, mediates F-actin network assembly, promoting autophagosome-lysosome fusion. HDAC6 is also responsible for the dynein-mediated transport and perinuclear concentration of altered mitochondria and protein aggregates.

In yeast cells, actin microfilaments are dispensable for bulk autophagy but necessary for selective types of autophagy like pexophagy. The yeast Arp2/3 complex, which is necessary for actin nucleation and F-actin formation, directly regulates the dynamics of Atg9.97 In mammalian cell lines, the actin network also has an important role in selective autophagy. Cortactin, known to interact with F-actin in promoting polymerization and branching, was recently identified as a new substrate of HDAC6.98 HDAC6 induces F-actin network formation around cytosolic aggregated proteins in a cortactin-dependent manner and promotes autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Thus, cortactin-dependent actin and HDAC6 distinguish quality control (QC) autophagy from starvation-induced autophagy for which these components are dispensable.29,50

HDAC6 and EP300-CREBBP Control Aggregosome Autophagy: Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases

HDAC6 recruits the autophagic machinery to aggresomes.28,30,31,50 Cells avoid accumulating potentially toxic protein aggregates by the suppression of misfolded protein using molecular chaperones and the selective degradation of misfolded proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Once aggregates have formed, they tend to be proteolysis resistant and accumulate in inclusion bodies (IBs).99 IBs are formed by dynein-dependent retrograde transport of aggregated proteins called aggresomes.100 The formation of aggresomes is thought to defend cells from the toxicity of protein aggregates by concentrating them to the microtubule organizing center.99,100 Proteins with expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) repeats accumulate in protein aggregates within intracellular IBs. The cytoplasmic and nuclear accumulation of IBs represents a pathological hallmark of most neurodegenerative diseases characterized by cognitive and motor deficits.

A growing body of evidence supports the hypothesis that autophagy is the main mechanism that mammalian cells use to eliminate protein aggregates.29,50,99,101 In mice and Drosophila, HDAC6 deficiency causes accumulation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates through the arrest of QC autophagy, resulting in age-dependent neurodegeneration.28 In Drosophila models of neurodegenerative diseases, HDAC6-mediated autophagy is also proposed to prevent impaired proteasome-related neurodegeneration, highlighting a compensatory relationship between these two degradation pathways.102 HDAC6 is a multidomain protein that possesses a C-terminal ZnF-UBP domain, which binds to polyubiquitin chains, and a dynein-binding domain.103,104 Thus, HDAC6 can associate with protein aggregates via ubiquitin association, and with the retrograde motor dynein as well, acting as a bridge allowing the targeting of protein aggregates for processing at the aggresome.105-107 HDAC6 also mediates the transport of constituents of the autophagic machinery to the aggresome and contributes to the transport of lysosomes to the site of autophagy.31

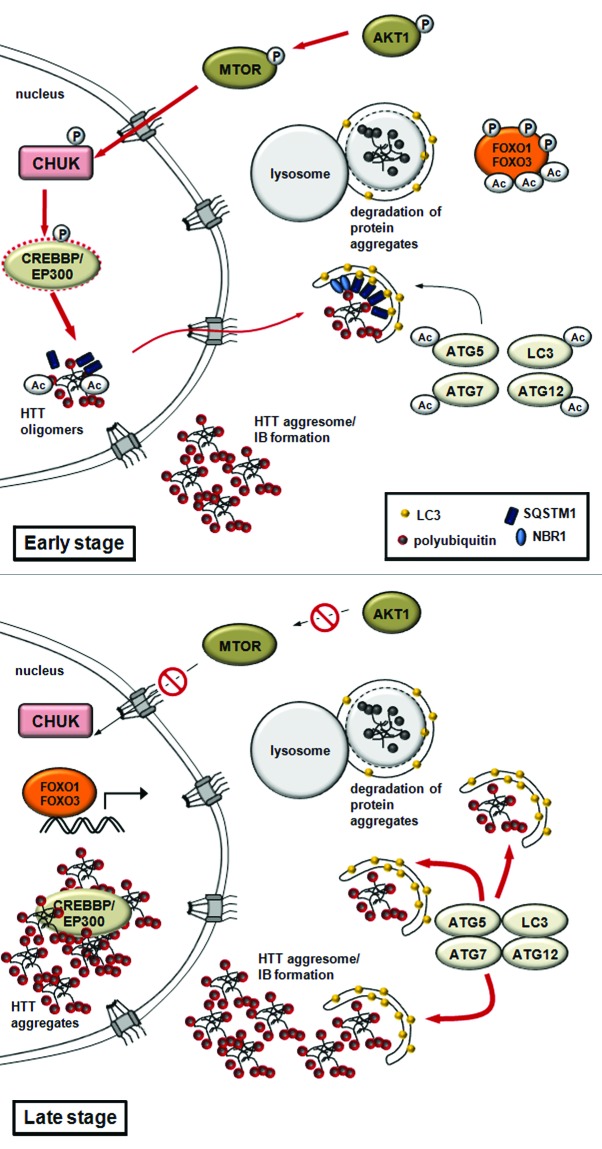

Expansion of glutamine repeats in the abnormal, cytotoxic huntingtin (HTT) protein provoke Huntington disease. The mutated and ubiquitinated aggregate-prone HTT protein accumulates in insoluble aggregates. HTT is phosophorylated by CHUK/IKK-α kinase, which enhances its subsequent poly-SUMOylation, which is responsible for targeting the protein to subnuclear structures called PML (promyelocytic leukemia) bodies. PML bodies contain the EP300-CREBBP acetyltransferase, which associates with the polyglutamine-containing domain of HTT.12,13,108,109 It was further shown that CREBBP overexpression or HDAC1 knockdown modulates the acetylation state of HTT at Lys444, promotes the incorporation of mutant HTT proteins into autophagosomes, and promotes its autophagy-mediated clearance, also termed aggrephagy.14,110,111 This clearance likely results from interaction with SQSTM1/p62 (sequestosome 1), a specific autophagy receptor.112-115 Remarkably, the activity of EP300-CREBBP is enhanced by the CHUK, inhibited by mutant HTT, and can be reversed by HDAC inhibitors or overexpression of EP300-CREBBP.13,15,109,116 IκB kinase and EP300-CREBBP-mediated QC autophagy is essential for the remobilization and degradation of intranuclear protein aggregates. Although the targets for EP300-CREBBP in the context of Huntington disease have not been identified, EP300-CREBBP may regulate the switch between QC autophagy (early stages) and autophagic cell death (late stages) in neuronal cells by controlling, as in other situations, the acetylation status of autophagic core components or regulatory proteins (such as ATG5, ATG7 and ATG12).17 In the advanced stage of neurodegeneration, EP300 and CREBBP incorporation and inactivation in IBs would result in decreased acetylation of ATG proteins17 and/or FOXO34 transcription factors. This would in turn lead to intensified autophagy and neuronal cell death (Fig. 5). While several aspects of this model remain to be experimentally addressed, the already established critical role for acetylation in the control of regulated autophagic clearance of mutant HTT provides an exciting therapeutic opportunity.

Figure 5. A model for quality control autophagy and nonselective autophagy in Huntington disease. The model proposes that EP300-CREBBP regulates the switch between QC autophagy and autophagic cell death in neuronal cells. In early stages, QC autophagy mediates the remobilization and degradation of HTT-containing protein aggregates. The activity of EP300-CREBBP is enhanced by CHUK. Acetylation by CREBBP facilitates the export of mutant intranuclear HTT proteins and promotes autophagy-mediated clearance (aggrephagy). This clearance is likely promoted by interaction with SQSTM1. In advanced stages of Huntington disease (late stage), the mutant HTT protein-containing inclusion bodies accumulate in the nucleus. This results in EP300-CREBBP sequestration and inhibition, and ultimately leads to intensified autophagy or autophagic cell death.

HDACs and HATs in Cancer

The autophagic process has been associated with the inhibition of tumor development.117,118 Hovewer, due to a dual function, promoting both cell death and cell survival,101,119 the role of autophagy remains highly controversial. This dual role of autophagy in tumorigenesis may result from cell- and stage-specificity. HDAC inhibitors are emerging as potent anticancer agents that can activate gene expression and enable elimination of malignant cells by apoptotic or autophagic cell death.24 Two potent HDAC inhibitors OSU-HDAC42 and SAHA induce autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through downregulation of AKT1-MTOR signaling and induction of an endoplasmic reticulum stress response.120 It was also reported that the HDAC inhibitor SAHA acts on HDAC7 and induces autophagic cell death of endometrial stromal sarcoma cells by influencing the MTOR pathway.27 SAHA also induces autophagy in chondrosarcoma and HeLa cells.41,47 H40 and SAHA induce autophagy in prostate cancer PC-3M cells possibily through the inhibition of HDAC3 and HDAC4 and CDKN1A/p21-mediated apoptosis.24,48 In conclusion, although the exact mechanisms underlying the anticancer activity of these drugs needs further clarification, the targeted induction of autophagic cell death by HDAC inhibitors is a promising therapeutic strategy to treat cancer.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Protein acetylation is widely used to control nonselective and selective autophagy in diverse physiological contexts. Components acting at multiple levels in the autophagic process appear to be targeted by acetylation, including the proteins of the core machinery of autophagy such as ATG proteins, regulatory proteins such as the FOXO transcription factors, and cytoskeletal proteins providing support for intracellular transport/movement required for autophagy. Further links between protein acetylation and autophagy control are likely to emerge. For instance, with the exception of NAA10/ARD1, an N-acetyltransferase identified as a suppressor of the MTOR signaling pathway, α-N-acetylation in autophagy regulation remains poorly explored (Table 1).121 Acetylation also plays a crucial regulatory role in pathological contexts, including neurodegenerative disease and cancer. Identifying mechanisms and proteins targeted by acetylation thus constitutes a promising avenue for specific drug design and the development of refined therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Saurin and Lajos Laszlo for critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the author’s laboratory is supported by the CNRS, Aix-Marseille Université and grants from CEFIPRA, FRM, ANR and ARC. We apologize to any investigator whose work owing to space limitation was not covered thoroughly or directly cited.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ATG

AuTophaGy-related

- CREBBP

CREB binding protein

- EP300

E1A binding protein p300

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HD

Huntington disease

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- KAT

lysine acetyltransferase

- KDAC

lysine deacetylase

- PML body

promyelocytic leukemia body

- PtdIns3K

phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase

- PTM

post-translational modification

- TOR

target of rapamycin

- IB

inclusion body

- AKT1

v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/23908

References

- 1.Singh R, Cuervo AM. Autophagy in the cellular energetic balance. Cell Metab. 2011;13:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubbard VM, Valdor R, Macian F, Cuervo AM. Selective autophagy in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis in aging organisms. Biogerontology. 2012;13:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizushima N. Autophagy in protein and organelle turnover. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:397–402. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.011023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sridhar S, Botbol Y, Macian F, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and disease: always two sides to a problem. J Pathol. 2012;226:255–73. doi: 10.1002/path.3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1383–435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEwan DG, Dikic I. The Three Musketeers of Autophagy: phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and acetylation. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang XJ, Seto E. Lysine acetylation: codified crosstalk with other posttranslational modifications. Mol Cell. 2008;31:449–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene. 2005;363:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadoul K, Wang J, Diagouraga B, Khochbin S. The tale of protein lysine acetylation in the cytoplasm. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:970382. doi: 10.1155/2011/970382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steffan JS, Kazantsev A, Spasic-Boskovic O, Greenwald M, Zhu YZ, Gohler H, et al. The Huntington’s disease protein interacts with p53 and CREB-binding protein and represses transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6763–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100110097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nucifora FC, Jr., Sasaki M, Peters MF, Huang H, Cooper JK, Yamada M, et al. Interference by huntingtin and atrophin-1 with cbp-mediated transcription leading to cellular toxicity. Science. 2001;291:2423–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1056784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong H, Then F, Melia TJ, Jr., Mazzulli JR, Cui L, Savas JN, et al. Acetylation targets mutant huntingtin to autophagosomes for degradation. Cell. 2009;137:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCampbell A, Taylor JP, Taye AA, Robitschek J, Li M, Walcott J, et al. CREB-binding protein sequestration by expanded polyglutamine. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2197–202. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.14.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pankiv S, Lamark T, Bruun JA, Øvervatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of p62/SQSTM1 and its role in recruitment of nuclear polyubiquitinated proteins to promyelocytic leukemia bodies. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5941–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.039925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee IH, Finkel T. Regulation of autophagy by the p300 acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6322–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807135200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin SY, Li TY, Liu Q, Zhang C, Li X, Chen Y, et al. GSK3-TIP60-ULK1 signaling pathway links growth factor deprivation to autophagy. Science. 2012;336:477–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1217032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi C, Ma M, Ran L, Zheng J, Tong J, Zhu J, et al. Function and molecular mechanism of acetylation in autophagy regulation. Science. 2012;336:474–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1216990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh M, Choi IK, Kwon HJ. Inhibition of histone deacetylase1 induces autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:1179–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie HJ, Noh JH, Kim JK, Jung KH, Eun JW, Bae HJ, et al. HDAC1 inactivation induces mitotic defect and caspase-independent autophagic cell death in liver cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao DJ, Wang ZV, Battiprolu PK, Jiang N, Morales CR, Kong Y, et al. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors attenuate cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015081108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moresi V, Carrer M, Grueter CE, Rifki OF, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 regulate autophagy flux and skeletal muscle homeostasis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121159109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rikiishi H. Autophagic and apoptotic effects of HDAC inhibitors on cancer cells. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:830260. doi: 10.1155/2011/830260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cernotta N, Clocchiatti A, Florean C, Brancolini C. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of HDAC4, a new regulator of random cell motility. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:278–89. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Jia X, Azab AK, Maiso P, Ngo HT, et al. microRNA-dependent modulation of histone acetylation in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2010;116:1506–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hrzenjak A, Kremser ML, Strohmeier B, Moinfar F, Zatloukal K, Denk H. SAHA induces caspase-independent, autophagic cell death of endometrial stromal sarcoma cells by influencing the mTOR pathway. J Pathol. 2008;216:495–504. doi: 10.1002/path.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthias P, Yoshida M, Khochbin S. HDAC6 a new cellular stress surveillance factor. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:7–10. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.1.5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JY, Yao TP. Quality control autophagy: A joint effort of ubiquitin, protein deacetylase and actin cytoskeleton. Autophagy. 2010;6:555–7. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.4.11812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwata A, Christianson JC, Bucci M, Ellerby LM, Nukina N, Forno LS, et al. Increased susceptibility of cytoplasmic over nuclear polyglutamine aggregates to autophagic degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13135–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505801102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwata A, Riley BE, Johnston JA, Kopito RR. HDAC6 and microtubules are required for autophagic degradation of aggregated huntingtin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40282–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung KH, Noh JH, Kim JK, Eun JW, Bae HJ, Chang YG, et al. Histone deacetylase 6 functions as a tumor suppressor by activating c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated beclin 1-dependent autophagic cell death in liver cancer. Hepatology. 2012;56:644–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.25699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3374–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hariharan N, Maejima Y, Nakae J, Paik J, Depinho RA, Sadoshima J. Deacetylation of FoxO by Sirt1 Plays an Essential Role in Mediating Starvation-Induced Autophagy in Cardiac Myocytes. Circ Res. 2010;107:1470–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeong JK, Moon MH, Lee YJ, Seol JW, Park SY. Autophagy induced by the class III histone deacetylase Sirt1 prevents prion peptide neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:146–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Y, Yang J, Liao W, Liu X, Zhang H, Wang S, et al. Cytosolic FoxO1 is essential for the induction of autophagy and tumour suppressor activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:665–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukherjee S, Ray D, Lekli I, Bak I, Tosaki A, Das DK. Effects of Longevinex (modified resveratrol) on cardioprotection and its mechanisms of action. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:1017–25. doi: 10.1139/Y10-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuo HP, Lee DF, Chen CT, Liu M, Chou CK, Lee HJ, et al. ARD1 stabilization of TSC2 suppresses tumorigenesis through the mTOR signaling pathway. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuo HP, Hung MC. Arrest-defective-1 protein (ARD1): tumor suppressor or oncoprotein? Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:56–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipinski MM, Hoffman G, Ng A, Zhou W, Py BF, Hsu E, et al. A genome-wide siRNA screen reveals multiple mTORC1 independent signaling pathways regulating autophagy under normal nutritional conditions. Dev Cell. 2010;18:1041–52. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto S, Tanaka K, Sakimura R, Okada T, Nakamura T, Li Y, et al. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) induces apoptosis or autophagy-associated cell death in chondrosarcoma cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(3A):1585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dompierre JP, Godin JD, Charrin BC, Cordelières FP, King SJ, Humbert S, et al. Histone deacetylase 6 inhibition compensates for the transport deficit in Huntington’s disease by increasing tubulin acetylation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3571–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0037-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe M, Adachi S, Matsubara H, Imai T, Yui Y, Mizushima Y, et al. Induction of autophagy in malignant rhabdoid tumor cells by the histone deacetylase inhibitor FK228 through AIF translocation. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:55–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu J, Shao CJ, Chen FR, Ng HK, Chen ZP. Autophagy induced by valproic acid is associated with oxidative stress in glioma cell lines. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:328–40. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robert T, Vanoli F, Chiolo I, Shubassi G, Bernstein KA, Rothstein R, et al. HDACs link the DNA damage response, processing of double-strand breaks and autophagy. Nature. 2011;471:74–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, Sun W, O’Connell TM, Bunger MK, et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao Y, Gao Z, Marks PA, Jiang X. Apoptotic and autophagic cell death induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408345102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long J, Zhao J, Yan Z, Liu Z, Wang N. Antitumor effects of a novel sulfur-containing hydroxamate histone deacetylase inhibitor H40. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1235–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez G, Torres K, Liu J, Hernandez B, Young E, Belousov R, et al. Autophagic survival in resistance to histone deacetylase inhibitors: novel strategies to treat malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:185–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee JY, Koga H, Kawaguchi Y, Tang W, Wong E, Gao YS, et al. HDAC6 controls autophagosome maturation essential for ubiquitin-selective quality-control autophagy. EMBO J. 2010;29:969–80. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwang JW, Chung S, Sundar IK, Yao H, Arunachalam G, McBurney MW, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced autophagy is regulated by SIRT1-PARP-1-dependent mechanism: implication in pathogenesis of COPD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;500:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morselli E, Mariño G, Bennetzen MV, Eisenberg T, Megalou E, Schroeder S, et al. Spermidine and resveratrol induce autophagy by distinct pathways converging on the acetylproteome. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:615–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Büttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1305–14. doi: 10.1038/ncb1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sapountzi V, Côté J. MYST-family histone acetyltransferases: beyond chromatin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1147–56. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0599-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grienenberger A, Miotto B, Sagnier T, Cavalli G, Schramke V, Geli V, et al. The MYST domain acetyltransferase Chameau functions in epigenetic mechanisms of transcriptional repression. Curr Biol. 2002;12:762–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00814-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miotto B, Sagnier T, Berenger H, Bohmann D, Pradel J, Graba Y. Chameau HAT and DRpd3 HDAC function as antagonistic cofactors of JNK/AP-1-dependent transcription during Drosophila metamorphosis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:101–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.359506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mariño G, Morselli E, Bennetzen MV, Eisenberg T, Megalou E, Schroeder S, et al. Longevity-relevant regulation of autophagy at the level of the acetylproteome. Autophagy. 2011;7:647–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.15191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Black JC, Mosley A, Kitada T, Washburn M, Carey M. The SIRT2 deacetylase regulates autoacetylation of p300. Mol Cell. 2008;32:449–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han Y, Jin YH, Kim YJ, Kang BY, Choi HJ, Kim DW, et al. Acetylation of Sirt2 by p300 attenuates its deacetylase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:576–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dong H, Czaja MJ. Regulation of lipid droplets by autophagy. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh R, Cuervo AM. Lipophagy: connecting autophagy and lipid metabolism. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:282041. doi: 10.1155/2012/282041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Juhász G, Puskás LG, Komonyi O, Erdi B, Maróy P, Neufeld TP, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies FKBP39 as an inhibitor of autophagy in larval Drosophila fat body. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1181–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Der Heide LP, Hoekman MF, Smidt MP. The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem J. 2004;380:297–309. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2005;24:7410–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang JY, Hung MC. Deciphering the role of forkhead transcription factors in cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1284–90. doi: 10.2174/138945011796150299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, Masiero E, Rudolf R, Del Piccolo P, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007;6:458–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sengupta A, Molkentin JD, Yutzey KE. FoxO transcription factors promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28319–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boccitto M, Kalb RG. Regulation of Foxo-dependent transcription by post-translational modifications. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1303–10. doi: 10.2174/138945011796150316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matsuzaki H, Daitoku H, Hatta M, Aoyama H, Yoshimochi K, Fukamizu A. Acetylation of Foxo1 alters its DNA-binding ability and sensitivity to phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11278–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502738102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tzivion G, Dobson M, Ramakrishnan G. FoxO transcription factors; Regulation by AKT and 14-3-3 proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1938–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chakrabarti P, English T, Karki S, Qiang L, Tao R, Kim J, et al. SIRT1 controls lipolysis in adipocytes via FOXO1-mediated expression of ATGL. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1693–701. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M014647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, et al. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306:1383–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grönke S, Mildner A, Fellert S, Tennagels N, Petry S, Müller G, et al. Brummer lipase is an evolutionary conserved fat storage regulator in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2005;1:323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kume S, Uzu T, Horiike K, Chin-Kanasaki M, Isshiki K, Araki S, et al. Calorie restriction enhances cell adaptation to hypoxia through Sirt1-dependent mitochondrial autophagy in mouse aged kidney. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1043–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI41376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang F, Tong Q. SIRT2 suppresses adipocyte differentiation by deacetylating FOXO1 and enhancing FOXO1’s repressive interaction with PPARgamma. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:801–8. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang F, Nguyen M, Qin FX, Tong Q. SIRT2 deacetylates FOXO3a in response to oxidative stress and caloric restriction. Aging Cell. 2007;6:505–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.L’Hernault SW, Rosenbaum JL. Chlamydomonas alpha-tubulin is posttranslationally modified by acetylation on the epsilon-amino group of a lysine. Biochemistry. 1985;24:473–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00323a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piperno G, Fuller MT. Monoclonal antibodies specific for an acetylated form of alpha-tubulin recognize the antigen in cilia and flagella from a variety of organisms. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2085–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature. 2002;417:455–8. doi: 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.North BJ, Marshall BL, Borra MT, Denu JM, Verdin E. The human Sir2 ortholog, SIRT2, is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:437–44. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Creppe C, Malinouskaya L, Volvert ML, Gillard M, Close P, Malaise O, et al. Elongator controls the migration and differentiation of cortical neurons through acetylation of alpha-tubulin. Cell. 2009;136:551–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Holmberg C, Katz S, Lerdrup M, Herdegen T, Jäättelä M, Aronheim A, et al. A novel specific role for I kappa B kinase complex-associated protein in cytosolic stress signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31918–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rahl PB, Chen CZ, Collins RN. Elp1p, the yeast homolog of the FD disease syndrome protein, negatively regulates exocytosis independently of transcriptional elongation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:841–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Geeraert C, Ratier A, Pfisterer SG, Perdiz D, Cantaloube I, Rouault A, et al. Starvation-induced hyperacetylation of tubulin is required for the stimulation of autophagy by nutrient deprivation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24184–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Köchl R, Hu XW, Chan EY, Tooze SA. Microtubules facilitate autophagosome formation and fusion of autophagosomes with endosomes. Traffic. 2006;7:129–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xie R, Nguyen S, McKeehan WL, Liu L. Acetylated microtubules are required for fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reed NA, Cai D, Blasius TL, Jih GT, Meyhofer E, Gaertig J, et al. Microtubule acetylation promotes kinesin-1 binding and transport. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ravikumar B, Acevedo-Arozena A, Imarisio S, Berger Z, Vacher C, O’Kane CJ, et al. Dynein mutations impair autophagic clearance of aggregate-prone proteins. Nat Genet. 2005;37:771–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jahreiss L, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. The itinerary of autophagosomes: from peripheral formation to kiss-and-run fusion with lysosomes. Traffic. 2008;9:574–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dynein-dependent movement of autophagosomes mediates efficient encounters with lysosomes. Cell Struct Funct. 2008;33:109–22. doi: 10.1247/csf.08005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rubinsztein DC, Ravikumar B, Acevedo-Arozena A, Imarisio S, O’Kane CJ, Brown SD. Dyneins, autophagy, aggregation and neurodegeneration. Autophagy. 2005;1:177–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.3.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosomes: biogenesis from scratch? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van der Vaart A, Mari M, Reggiori F. A picky eater: exploring the mechanisms of selective autophagy in human pathologies. Traffic. 2008;9:281–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Monastyrska I, He C, Geng J, Hoppe AD, Li Z, Klionsky DJ. Arp2 links autophagic machinery with the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1962–75. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang X, Yuan Z, Zhang Y, Yong S, Salas-Burgos A, Koomen J, et al. HDAC6 modulates cell motility by altering the acetylation level of cortactin. Mol Cell. 2007;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kopito RR. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:524–30. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Johnston JA, Ward CL, Kopito RR. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1883–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pandey UB, Batlevi Y, Baehrecke EH, Taylor JP. HDAC6 at the intersection of autophagy, the ubiquitin-proteasome system and neurodegeneration. Autophagy. 2007;3:643–5. doi: 10.4161/auto.5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seigneurin-Berny D, Verdel A, Curtet S, Lemercier C, Garin J, Rousseaux S, et al. Identification of components of the murine histone deacetylase 6 complex: link between acetylation and ubiquitination signaling pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8035–44. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8035-8044.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zou H, Wu Y, Navre M, Sang BC. Characterization of the two catalytic domains in histone deacetylase 6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kawaguchi Y, Kovacs JJ, McLaurin A, Vance JM, Ito A, Yao TP. The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell. 2003;115:727–38. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00939-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pandey UB, Nie Z, Batlevi Y, McCray BA, Ritson GP, Nedelsky NB, et al. HDAC6 rescues neurodegeneration and provides an essential link between autophagy and the UPS. Nature. 2007;447:859–63. doi: 10.1038/nature05853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, Lin T, Ikeda AK, Simms-Waldrip T, Fu C, Sakamoto KM. Role of the aggresome pathway in cancer: targeting histone deacetylase 6-dependent protein degradation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2557–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Van Damme E, Laukens K, Dang TH, Van Ostade X. A manually curated network of the PML nuclear body interactome reveals an important role for PML-NBs in SUMOylation dynamics. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:51–67. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Steffan JS, Bodai L, Pallos J, Poelman M, McCampbell A, Apostol BL, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2001;413:739–43. doi: 10.1038/35099568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Øverbye A, Fengsrud M, Seglen PO. Proteomic analysis of membrane-associated proteins from rat liver autophagosomes. Autophagy. 2007;3:300–22. doi: 10.4161/auto.3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:603–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1: a missing link between protein aggregates and the autophagy machinery. Autophagy. 2006;2:138–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Clausen TH, Lamark T, Isakson P, Finley K, Larsen KB, Brech A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 and ALFY interact to facilitate the formation of p62 bodies/ALIS and their degradation by autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:330–44. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.3.11226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bates EA, Victor M, Jones AK, Shi Y, Hart AC. Differential contributions of Caenorhabditis elegans histone deacetylases to huntingtin polyglutamine toxicity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2830–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3344-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Levine B. Cell biology: autophagy and cancer. Nature. 2007;446:745–7. doi: 10.1038/446745a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Cleveland JL. Modulating autophagy for therapeutic benefit. Autophagy. 2007;3:464–7. doi: 10.4161/auto.4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu YL, Yang PM, Shun CT, Wu MS, Weng JR, Chen CC. Autophagy potentiates the anti-cancer effects of the histone deacetylase inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Autophagy. 2010;6:1057–65. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fisher TS, Etages SD, Hayes L, Crimin K, Li B. Analysis of ARD1 function in hypoxia response using retroviral RNA interference. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17749–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]