Abstract

Most humans are right-handed and, like many behavioral traits, there is good evidence that genetic factors play a role in handedness. Many researchers have argued that nonhuman animal limb or hand preferences are not under genetic control but instead are determined by random, non-genetic factors. We used quantitative genetic analyses to estimate the genetic and environmental contributions to three measures of chimpanzee handedness. Results revealed significant population-level handedness for two of the three measures --- the tube task and manual gestures. Furthermore, significant additive genetic effects for the direction and strength of handedness were found for all three measures, with some modulation due to early social rearing experiences. These findings challenge historical and contemporary views of the mechanisms underlying handedness in nonhuman animals.

One feature of human behavior is right-handedness. Though there is some cultural variation (Perelle & Ehrman, 1994, Porac & Coren, 1981, Raymond & Pontier, 2004), around 90% of humans are right-handed and the archaeological record dates right-handedness to at least 2 mya (Uomini, 2009), suggesting it has a long evolutionary history. Studies of families and twins suggest that handedness has a genetic component (Carter-Saltzman, 1980, Hicks & Kinsbourne, 1976, Klar, 1999, Medland et al., 2009, Sicotte et al., 1999, Warren et al., 2012). Overall, these studies indicate that about 25% of the variability in handedness is attributable to shared genetic factors and that 75% of the variability is due to shared environmental factors. Several genetic models have been proposed to explain the near universal expression of human right handedness (Annett, 2002, Corballis et al., 2012, Klar, 1999, Laland et al., 1995, Mcmanus & Bryden, 1992, Yeo et al., 2002). Though both single and two allele genetic models of human handedness have been hypothesized, each model proposes that right-handedness is genetically coded and that left-handedness is a consequence of random non-genetic factors. Environmental factors, including prenatal position in the fetus (Previc, 1991), early asymmetrical intrinsic and extrinsic stimulation (Michel, 1981), and social learning (Provins, 1997) have also been proposed explanations for the preponderance of human right-handedness. Lastly, it has been hypothesized that the asymmetrical function of the brain and behavior offer selective advantages in some species and therefore laterality has some evolutionary benefit (Ghirlanda & Vallortigara, 2004). This model proposes that divided functions between two hemispheres has a computational advantage and that coordination of social behavior among conspecifics may have selected for conformity for consistent left-right differences in behavior and the brain (Ghirlanda & Vallortigara, 2004).

Historically population-level handedness has been considered uniquely human, having evolved as a specific adaptation shortly after the Pan-Homo split (Bradshaw & Rogers, 1993, Corballis, 1992, Warren, 1980). This historical view was supported primarily by two bodies of research. First, there was little if any evidence of population-level limb and hand preferences in nonhuman primates and more distantly related vertebrates (Corballis, 1992, Warren, 1980). Second, early attempts to selectively breed for directional paw preferences in mice were unsuccessful (Collins, 1975, Collins, 1985), leading some to conclude that directional biases, unlike human handedness, were not under genetic control but influenced by random environmental factors in nonhuman animals (Warren, 1980).

The late evolutionary emergence of handedness has recently been challenged. For example, population-level behavioral asymmetries have been found in vertebrates (Macneilage et al., 2009, Rogers & Andrew, 2002, Strockens et al., in press, Vallortigara & Rogers, 2005) and even some invertebrates (Fransnelli et al., 2012). There is also some evidence that behavioral asymmetries in fish and chimpanzees may be under genetic influence (Bisazza et al., 2000b) but the exact contribution of genetic to non-genetic factors is unclear from these reports (but see Vallortigara & Bisazza, 2002). With specific reference to handedness, though there is some inconsistency in findings between species, studies in nonhuman primates have revealed evidence of population-level biases, particularly among great apes (Fagot et al., 1991, Hook-Costigan & Rogers, 1997, Hopkins, 2006, Macneilage et al., 1987, Mcgrew & Marchant, 1997). For instance, to date more than 500 chimpanzees from four different populations have been tested for hand use on a task requiring coordinated bimanual actions called the tube task (Hopkins et al., 2011, Llorente et al., 2010) and small but significant right hand biases have been found in each sample population. Further, based on the distribution of handedness for several tasks in chimpanzees, Annett (2006) suggested that a possible genetic basis might be present in this species, though expressed less strongly than in humans

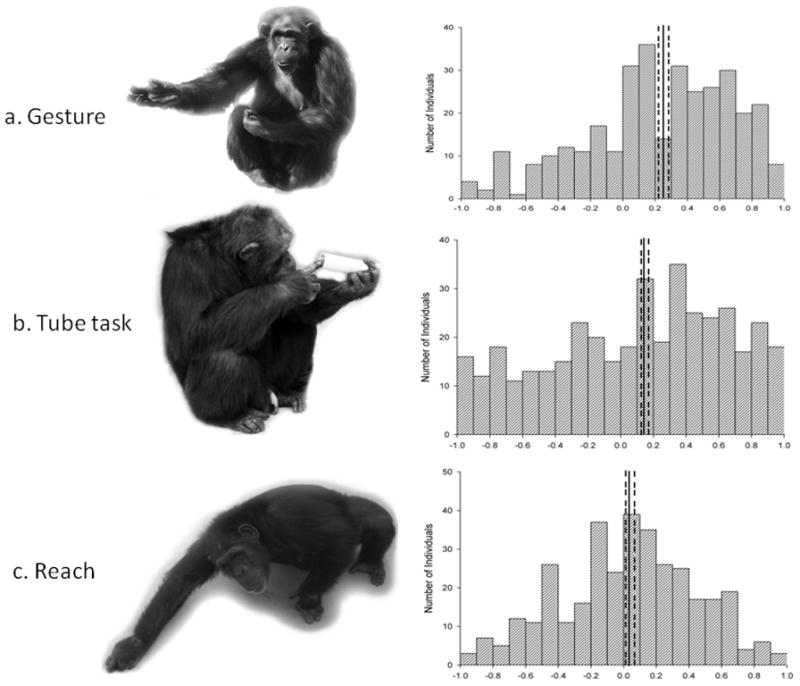

We sought to estimate the degree to which genetic and environmental effects contribute to chimpanzee handedness across several tasks (see Figure 1a). To estimate contributions of genetic and environmental factors to the expression of handedness, we capitalized on two attributes of captive chimpanzees residing in different research facilities within the United States. First, the existence of well documented pedigrees dating back, in many cases, to the founder animals allowed us to determine precise measures of relatedness among all the apes in the sample. Second, for a variety of reasons unrelated to the present study, some chimpanzees housed in these research facilities have been reared primarily by humans in nursery type settings. In contrast, others were born and raised in social groups of conspecifics. As many of these differently reared individuals are related, we are able to compare the heritability of handedness among individuals raised in very different early social environments.

Figure 1.

Left column: Pictures depicting chimpanzees performing each handedness tasks a) manual gesturing b) performing the tube task and c) simple reaching. Right column: Histograms depicting the handedness distribution based on HI scores for a) manual gestures b) tube task and c) simple reaching. Dark bar indicates mean HI score for each task and the dotted bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. Manual gestures and the tube task showed a population-level right-hand skew.

Methods

Subjects

Data were collected from captive chimpanzees living in three research facilities including the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, and Alamogordo Primate Facility. Hand preference was measured with three tasks including simple reaching (n = 345; 189 females, 156 males), manual gestures (n = 347; 195 females, 152 males) and the tube task (n = 542; 304 females, 238 males), a measure of hand use for coordinated bimanual actions. Samples sizes varied across tasks depending upon the availability of subjects for testing and subjects’ willingness to perform the tasks. Within each cohort, there were mother- and human-reared chimpanzees. Human-reared chimpanzees were separated from their mothers within the first 30 days of life, due to unresponsive care, injury, or illness (Bard, 1994, Bard et al., 1992). These chimpanzees were placed in incubators, fed standard human infant formula (non-supplemented), and cared for by humans until they were sufficiently able to care for themselves, at which time they were placed with other infants of the same age until they were 3 years old (Bard, 1994, Bard et al., 1992). At 3 years of age, human-reared chimpanzees were integrated into larger social groups of adult and sub-adult chimpanzees. Mother-reared chimpanzees were not separated from their mother for at least 2.5 years of life and were raised in nuclear family groups ranging from 4 to 20 individuals.

Handedness Measures

Simple Reaching

On the first trial, a raisin was thrown into the subject’s home enclosure. The raisin was thrown by the experimenter to a location at least three meters from the subject, such that they had to locomote to the location of the raisin, pick up the raisin and bring it to their mouth for consumption. When the chimpanzee picked up the raisin, the experimenter recorded the hand used as left or right. One and only one reaching response was recorded each trial to ensure independence of data. The trial ended after subjects retrieved the raisin. For all subsequent trials, subjects were required to locomote at least three strides between reaching responses to allow for postural readjustment between trials. A median of 51 reaching responses were obtained from each subject (range = 11 to 145).

The Tube Task

Each chimpanzee received two tests and a minimum of 30 responses were obtained from each chimpanzee. For the tube task, peanut butter is smeared on the inside edges of polyvinyl chloride tubes approximately 15 cm in length and 2.5 cm in diameter. Peanut butter is smeared on both ends of the tube and is placed far enough down the tube such that the subjects cannot lick the contents completely off with their mouths, but rather must use one hand to hold the tube and the other hand to remove the peanut butter. The tubes were handed to subjects in their home enclosures and a focal sampling technique was used to collect individual data from each subject. The median number of responses obtained from each subject was 67 (range = 1 to 759).

Manual Gestures

At the onset of each trial, an experimenter would approach the chimpanzee’s home cage and center themselves in front of the chimpanzee at a distance of approximately 1.0–1.5 m. If the chimpanzee was not already positioned in front of the experimenter at the onset of the trial, the chimpanzee would immediately move towards the front of the cage when the experimenter arrived with the food. The experimenter then called the chimpanzee’s name and offered a piece of food until the chimpanzee produced a manual gesture. Only responses in which the chimpanzee unimanually extended his or her digit(s) through the cage mesh to request the food were considered a response. Other possible manual responses such as cage banging or clapping were not counted as a gesture. Two-handed gestures, although rare, were not scored, nor were gestures that were produced by the chimpanzee prior to the experimenter arriving in front of the chimpanzee’s home cage. The median number of manual gesture responses obtained from each subject was 33 (range 2 to 492).

Hand Preference Calculation

For each subject and measure, a handedness index was calculated following the formula [HI = (R − L) / (R + L)] where R and L indicated the frequencies in left and right hand use. HI values ranged from −1.0 to 1.0 with positive values indicating right hand preferences and negative values indicating left hand preferences. We used the HI indices to visualize the distribution of handedness and to classify subjects into handedness categories for descriptive purposes.

Heritability Analysis

We estimated the heritability of the measures with a generalized linear mixed ‘animal model’ (Kruuk, 2004, Lynch & Walsh, 1998, Wilson et al., 2009) that decomposes the phenotypic variance into genetic and environmental effects. We conducted the analyses using Bayesian estimators to more readily incorporate the non-normal distribution of the data (proportions of hand use) and to be able to test alternative hypotheses even if data for a given parameter estimate was sparse. The models included sex and rearing status as fixed effects. We conducted the same model building procedure on the directional and strength measures of handedness data.

Using the whole sample of both human- and mother-reared chimpanzees, we first estimated the narrow-sense heritability, which captures the proportion of resemblance between relatives attributable to transmitted genes. The residual variance in this model captured the unique environment variance, an estimate of effects that make related individuals differ from one another. Additive genetic variance was fit using the additive genetic relationship matrix of pairwise relatedness among individuals constructed from the pedigree of the whole sample. We fit a multivariate model using all three handedness measures for either direction or strength to estimate the variance of each measure and the covariances among measures.

In a Bayesian analysis, known or assumed information about the parameters being estimated can be set up in their prior distribution. The prior distribution is then combined with the likelihood from the data to yield a sample from the posterior probability distribution of model parameters. The variance components were modeled as being drawn from an Inverse-Wishart distribution, which has two parameters: a matrix describing where the distribution is centered and a shape (or “degree of belief”) parameter that specifies how tightly concentrated the distribution is around its center. We used a prior matrix for the additive genetic variance that was equivalent to heritability of .25 and a shape parameter (ν = 3) that was non-informative for the heritability of each measure. In other words, we specified a prior probability for the heritability that was uniform between 0 and 1. Each proportional outcome, i.e. number of observed uses of right and left hands, on a particular task was treated as binomially distributed (where, arbitrarily, right hand = “success” for directional bias and dominant hand = “success” for strength) using a logit link function. We calculated heritability on the latent scale as σ2A / (σ2A + σ2E) where σ2A is the additive genetic variance and σ2E is the residual variance. We did not include the distribution specific variance (π2/3) in the denominator to yield heritability as a repeatability on the original scale (Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2010), which would be more appropriate for phenotypes expressed a limited number of times. The heritability estimates take out measurement error and adjust for fixed effects. We also used this model to estimate the genetic and environmental correlations among the handedness measures. A genetic correlation represents the extent to which hand use in the different tasks is influenced by the same genetic effects while the environmental correlations are from effects unique to each individual.

We next tested whether the heritability of each measure differed by rearing status. To determine this we constructed bivariate models for each measure by considering the same handedness measure in the mother- or human-reared environments as two separate traits (Falconer, 1952, Lynch & Walsh, 1998). Although individuals only had values for the environment they were raised in, the genetic covariance could be estimated across environments because chimpanzees had relatives who were reared in the different environment. We examined the proportion of samples for which the trait’s heritability in the human-reared condition was less than for the mother-reared condition. We used a prior with a shape parameter ν = 3 that gave equal prior probability for a correlation over the range −1 to +1. Because individuals were reared in only one environment, there was no information to estimate a residual covariance so it was fixed to zero in all of these models.

Then, using only the mother-reared chimpanzees, we estimated the effect of the maternal environment on handedness using maternal ID as the predictor. The maternal environment variance captures non-genetic sources of resemblance between siblings, such as from the intrauterine environment or early learning from the mother. In pedigree-based models it also captures non-additive genetic variance that contributes to resemblance between siblings but not between parents and offspring (Wilson et al., 2009).

We fit models by Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation using MCMCglmm (Hadfield, 2010) in R (R Development Core Team, 2012). We modeled the distribution of the outcomes using the multinomial2 family, first verifying that an additive over-dispersion model was appropriate by regressing each proportional outcome on sex and rearing status using a generalized linear model with a quasi-binomial error structure and checking that the over-dispersion parameter was > 1. We ran each model four times for 1 × 106 MCMC iterations, discarded the first half of each chain and thinned them to 1000 samples to represent the joint posterior distribution. We also experimented with different priors for the additive genetic variance of 10, 25, and 50% of the adjusted phenotypic variance. We monitored convergence of the chains by, for each parameter, checking that the difference in means of the first 10% and the last 50% of the sample (Geweke, 1992) had z-scores < |2| and that the autocorrelation between retained samples was < .1 using the coda package (Plummer et al., 2006) and by a visual inspection of the trace plots.

We combined the posterior distributions from each run of a model to make parameter inferences. To determine population-level preference, we calculated the average handedness index using the model-estimated means. This index represents the expected proportion of hand use in a given task for a “genetically average” chimpanzee and averaging over sex and rearing condition effects. We determined whether there was a significant right-hand (or left-hand) bias using a two-tailed p-value as twice the proportion of samples that were above (or below) 0.

We summarized parameter estimates using means and 95% coverage intervals (CI) and compared models using the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) averaged over four runs of each model. The lowest DIC is considered the best model in terms of using a model to predict future data (Gelman et al., 2004). The DIC can be used to compare models in terms of the parameters they fit and the priors used for those parameters.

Results

We used the model-estimated fixed effect intercepts (conditioning over effects of sex, rearing status, and relatedness among subjects) to calculate mean HI scores for each measure to determine if they differed from a hypothetical value of zero, which would be the predicted HI value if there was no population-level hand preference or if preference were bimodally distributed. Population-level right handedness was found for the tube task (mean HI = .20, 95% coverage interval [CI] = .19–.29, p < .001) and for manual gestures (.28, CI = .21–.37, p < .001) but not simple reaching (.02, CI = −.04–.09, p = .47) (Figure 1). Neither sex nor rearing history was significantly associated with hand preference. Chimpanzees on average used their dominant hand 68% of the time for simple reaching (CI = 67–70%), 74% (CI = 72–76%) of the time for gesturing, and 80% (CI = 79–82%) of the time in the tube task. Direction of simple reaching was phenotypically correlated with both the gesture (r = .22, p < .01) and tube tasks (r = .26, p < .01), though these latter two measures were not significantly correlated (r = .05, p > .05). For the absolute value of the handedness index, representing handedness strength, only the reach and tube tasks were significantly correlated.

Heritability Analyses

The direction and strength of handedness showed moderate and significant heritability for all three tasks. It should also be noted that estimates of heritability were higher for strength compared to direction in hand use for all three tasks (see Table 1). Using alternative priors had little effect on the heritability estimates. For mother-reared individuals, the maternal environment contributed moderately to variance in handedness for all three measures. The heritability of direction for mother-reared individuals was higher for the reach and tube tasks but lower for the gesture task. Of these only the heritability of direction for the tube task was significantly different between rearing conditions (p = .03).

Table 1.

Variance Proportion Coefficients for Each Handedness Measure

| Direction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Rearing | VPC | Reach | Gesture | Tube |

| 1. Genetic effects | All | h2 | .36 (.19–.61) | .34 (.18–.56) | .24 (.10–.43) |

|

| |||||

| 2. Rearing status | Human | h2 | .36 (.17–.65) | .43 (.17–.79) | .22 (.08–.48) |

|

| |||||

| Mother | h2 | .49 (.26–.75) | .37 (.18–.62) | .48 (.22–.75) | |

|

| |||||

| 3. Maternal effects | Mother | h2 | .46 (.25–.70) | .39 (.18–.68) | .61 (29–.83) |

| m2 | .38 (.21–.56) | .24 (.13–.38) | .23 (.10–.38) | ||

| Strength | |||||

| Model | Rearing | VPC | Reach | Gesture | Tube |

|

| |||||

| 1. Genetic effects | All | h2 | .67 (.40–.97) | .46 (.28–.69) | .44 (.27–.62) |

|

| |||||

| 2. Rearing status | Human | h2 | .61 (.40–.81) | .48 (.24–.76) | .48 (.25–.73) |

|

| |||||

| Mother | h2 | .58 (.38–.76) | .49 (.30–.70) | .49 (.27–.72) | |

|

| |||||

| 3. Maternal effects | Mother | h2 | .47 (.31–.63) | .51 (.32–.69) | .45 (.24–.68) |

| m2 | .48 (.32–.64) | .40 (.25–.55) | .31 (.18–.48) | ||

Parameter estimate means given with 95% coverage intervals in brackets. VPC = variance proportion coefficient. h2 = narrow-sense heritability, m2 = maternal environment coefficient, calculated as repeatabilities on the latent scale.

Genetic and Environmental Correlations Across Tasks

None of the genetic correlations among the measures, indicating the extent to which handedness in each task is influenced by the same set of genes, was significantly different from 0 (Table 2). However, we did identify a significant genetic correlation between hand preference for simple reaching and the tube task for mother-reared individuals. The unique environmental correlations between reach-gesture and reach-tube for handedness direction, but not for strength, were also significantly positive.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Handedness Measures

| Direction | Strength | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic | ||||

| Reach | Gesture | Reach | Gesture | |

| Gesture | .22 (.11, .32) | .05 (−.06, .15) | ||

| Tube | .26 (.16, .36) | .05 (−.06, .15) | .14 (.03, .24) | −.09 (−.19, .02) |

|

| ||||

| Additive Genetic | ||||

| Reach | Gesture | Reach | Gesture | |

| Gesture | −.01 (−.40, .57) | .14 (−.28, .47) | ||

| Tube | .33 (−.24, .62) | .03 (−.44, .49) | .09 (−.23, .46) | −.28 (−.58, .04) |

|

| ||||

| Additive Genetic (mother) | ||||

| Reach | Gesture | Reach | Gesture | |

| Gesture | −.18 (−.57, .45) | .26 (−.21, .49) | ||

| Tube | .45 (.01, .81) | −.21 (−.63, .38) | −.01 (−.36, .33) | −.40 (−.64, .03) |

|

| ||||

| Additive Genetic (human) | ||||

| Reach | Gesture | Reach | Gesture | |

| *Gesture | .44 (−.43, .78) | −.06 (−.44, .38) | ||

| Tube | .56 (−.31, .82) | .67 (−.40, .78) | .25 (−.82, 1.0) | −.34 (−.67, .29) |

|

| ||||

| Unique environmental | ||||

| Reach | Gesture | Reach | Gesture | |

| Gesture | .26 (.07, .57) | −.08 (−.82, .42) | ||

| Tube | .36 (.11, .51) | .08 (−.13, .29) | .26 (−.23, .46) | .05 (−.21, .37) |

|

| ||||

| Maternal environmental | ||||

| Reach | Gesture | Reach | Gesture | |

| Gesture | .00 (−.42, .40) | −.03, (−.36, .27) | ||

| Tube | .37 (−.03, .71) | −.04 (−.44, .44) | .10 (−.22, .42) | −.12 (−.41, .28) |

Phenotypic correlations point estimates from handedness indices with 95% confidence intervals in brackets. Additive genetic, unique environment, and maternal environment correlations from animal model with posterior mode and 95% coverage intervals in brackets. Correlations significantly different from 0 highlighted in bold.

fDiscussion

Consistent with human family and twin studies (Francks et al., 2002), we found that directional bias and strength were heritable in chimpanzees. In addition, we found that strength of laterality appeared to be under greater genetic control than direction. This finding is somewhat consistent with previous results on selective breeding for paw preferences in mice (Collins, 1985) that show that the strength but not direction of paw preferences can be selectively bred; however, unlike mice, directional biases in hand preference were also heritable in the chimpanzees. It is thus likely that, in chimpanzees, a similar genetic mechanism might code for strength of hand preference and that directional biases are subsequently induced by consistent post-natal environmental factors. These early social experiential factors might then, in turn, interact with genetic factors in the determination of directional biases in hand use. In short, genetic factors play a significant role in determining handedness but post-natal environmental variables may have a significant additive effect on their expression. The role that environmental mechanisms play on the development of behavioral asymmetries in vertebrates has been studied extensively (Rogers et al., 2013). What post-natal environmental mechanisms might influence chimpanzee handedness is not clear. However, there are several candidates among lateralized behavioral traits in chimpanzee neonates and mothers (Fagot & Bard, 1995, Hopkins, 2004, Hopkins & Bard, 1995, Hopkins & Bard, 2000, Hopkins & De Lathouwers, 2006, Manning et al., 1994), including asymmetries in head orientation or lateral biases in maternal cradling or nipple preferences. We also cannot rule out that observations of maternal hand use by the offspring might have some impact on handedness. Any of these explanations is consistent with the moderate effect from the maternal environment found in mother-reared individuals. We found some evidence for genetic effects differing between rearing environments, where the heritability of the tube task was higher among mother-reared individuals. One possibility is that factors in the human-reared environment override the individual’s genetic predisposition, at least with respect to the tube task.

The results further showed that there were significant unique environmental correlations between reaching and manual gesture, and the tube task, though the associations were not particularly strong. In contrast, the genetic correlations were weak and the only correlation significantly different from zero was found in mother-reared individuals. These findings differ from some reports of the heritability of human hand preferences (Medland et al., 2009, Warren et al., 2012) where genetic correlations among tasks are usually significant. This suggests a possible species differences in the genetic architecture underlying human and chimpanzee handedness.

One caution in making comparisons between human and chimpanzee handedness is the tasks used to assess hand preference and the manner in which they are selected. Human handedness is typically quantified by use of questionnaire and the items placed on the survey have been explicitly developed to measure the construct handedness. In other words, the questionnaire items are selected, a priori, to measure handedness. In contrast, the measures used in this and many studies of nonhuman primate handedness, are typically obtained by observing hand use. Moreover, the behaviors measured are often selected based on convenience rather than whether they elicit reliable hand use in each individual. These varying approaches may potentially explain the differences in genetic correlations between tasks and warrants further investigation, using approaches not unlike those recently employed by Forrester and colleagues (Forrester et al., 2011b, Forrester et al., 2011a, Forrester et al., 2012).

In summary, the findings reported here extend the handedness literature by reporting on the quantitative estimation of heritability in chimpanzee, and, indeed, nonhuman primate hand preferences (but see Fears et al., 2011). The overall results show that population-level task specific handedness was present in the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees 5–6 mya and was under some genetic control at that time. What advantages and disadvantages are explicitly linked to handedness remains unclear but one possibility is that asymmetrical functions conferred some adaptive advantage in either cognitive and/or motor functions that increased fitness for certain individuals or populations (Vallortigara & Rogers, 2005). In chimpanzees, the most obvious potential lateralized behavior under selection would likely have been in the realm of tool use (Mcgrew & Marchant, 1999) but this remains to tested. Nonetheless, as others have argued, duality of function as an adaptive function can be accomplished without the emergence of population-level asymmetries (Ghirlanda & Vallortigara, 2004). Thus, other evolutionary factors may have come into play in the emergence of population-level asymmetries such as the need for cooperation in complex social systems (for example in fish, see Bisazza et al., 2000a). Further studies on the role of genes and experiential factors on the development of handedness and other aspects of behavioral lateralization will provide invaluable data on the evolution of hemispheric specialization in primates, including humans.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants NS-42867, NS-73134, HD-56232 and HD-60563 and Cooperative Agreement RR-15090. We appreciate assistance of Jamie Russell, Jennifer Schaeffer, Dr. Steve Schapiro and Molly Gardner for assistance in data collection. American Psychological Association and Institute of Medicine guidelines for the treatment of chimpanzees in research and were followed during all aspects of this study.

Literature Cited

- Annett M. Handedness and brain asymmetry: The right shift theory. Psychology Press; Hove: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Annett M. The distribtion of handedness in chimpanzees: Estimating right shift from the Hopkins’ sample. Laterality. 2006;11:101–109. doi: 10.1080/13576500500376500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard KA. Evolutionary roots of intuitive parenting: Maternal competence in chimpanzees. Early Development and Parenting. 1994;3:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bard KA, Platzman KA, Lester BM, Suomi SJ. Orientation to social and nonsocial stimuli in neonatal chimpanzees and humans. Infant Behavior and Development. 1992;15:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bisazza A, Cantalupo C, Capocchiano M, Vallortigara G. Population lateralization and social behavior: A study with sixteen species of fish. Laterality. 2000a;5:269–284. doi: 10.1080/713754381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisazza A, Facchin L, Vallortigara G. Heritability of lateralization in fish: concordance of right-left asymmetry between parents and offspring. Neuropsychologia. 2000b;38:907–912. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw B, Rogers L. The evolution of lateral asymmetries, language, tool-use and intellect. Academic Press; San Diego: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Saltzman L. Biological and sociocultural effects on handedness: comparison between biological and adoptive parents. Science. 1980;209:1263–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.7403887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL. When left-handed mice live in a right handed world. Science. 1975;187:181–184. doi: 10.1126/science.1111097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL. On the inheritance of direction and degree of asymmetry. In: Glick S, editor. Cerebral lateralization in non-human species. Academic Press; Orlando: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC. The lopsided brain: Evolution of the generative mind. Oxford University Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC, Badzakova-Trajkov G, Haberling IS. Right hand, left brain: genetic and evolutionary basis of cerebral asymmetries for language and manual action. WIREs Cognitive Science. 2012;3:1–17. doi: 10.1002/wcs.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot J, Bard KA. Asymmetric grasping response in neonate chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Infant Behavior and Development. 1995;18:253–255. [Google Scholar]

- Fagot J, Drea C, Wallen K. Asymmetrical hand use in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) in tactually and visually regulated tasks. J Comp Psychol. 1991;105:260–268. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.105.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS. The Problem of Environment and Selection. The American Naturalist. 1952;86:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Fears SC, Scheibel K, Abaryan Z, Lee C, Service SK, Jorgensen MJ, Fairbanks LA, Cantor RM, Freimer NB, Woods RP. Anatomic brain asymmetry in vervet monkeys. PlosOne. 2011;6:e28243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester GS, Leavens DA, Quaresmini C, Vallortigara G. Target animacy influences gorilla handedness. Anim Cogn. 2011a;14:903–907. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester GS, Leavens DA, Quaresmini C, Vallortigara G. Target animacy influences gorilla handedness. Anim Cogn. 2011b;14:903–907. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester GS, Quaresmini C, Leavens DA, Spiezio C, Vallortigara G. Target animacy influences chimpanzee handedness. Anim Cogn. 2012:1121–1127. doi: 10.1007/s10071-012-0536-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francks C, Fisher SE, MacPhie L, Richardson AJ, Marlow AJ, Stein JF. A genomewide linkage screen for relative hand skill in sibling pairs. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;70:800–805. doi: 10.1086/339249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransnelli E, Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ. Left-right asymmetries of behaviour and nervous system in invertebrates. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review. 2012;36:1273–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Rubin DB. Bayesian data analysis. Chapman & Hall; Boca Raton, FL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Geweke J. Evaluating the accuracy of sampling-based approaches to calculating posterior moments. In: Bernado JM, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Smith AFM, editors. Bayesian Statistics. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1992. pp. 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ghirlanda S, Vallortigara G. The evolution of brain lateralization: a game-theoretical analysis of population structure. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2004;271:853–857. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield JD. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: The MCMCglmm R package. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks R, Kinsbourne M. Genetic basis for human handedness: Evidence from a partial cross-fostering study. Science. 1976;192:908–910. doi: 10.1126/science.1273577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook-Costigan MA, Rogers LJ. Hand preferences in New World primates. International Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1997;9:173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD. Laterality in maternal cradling and infant positional biases: Implications for the evolution and development of hand preferences in nonhuman primates. Int J Primatol. 2004;25:1243–1265. doi: 10.1023/B:IJOP.0000043961.89133.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD. Comparative and familial analysis of handedness in great apes. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:538–559. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Bard KA. Evidence of asymmetries in spontaneous head turning in infant chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:808–812. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.4.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Bard KA. A longitudinal study of hand preference in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Dev Psychobiol. 2000;36:292–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, De Lathouwers M. Left nipple preferences in infant Pan paniscus and Pan troglodytes. Int J Primatol. 2006;27:1653–1662. doi: 10.1007/s10764-006-9086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Phillips KA, Bania A, Calcutt SE, Gardner M, Russell JL, Schaeffer JA, Lonsdorf EV, Ross S, Schapiro SJ. Hand preferences for coordinated bimanual actions in 777 great apes: Implications for the evolution of handedness in Hominins. J Hum Evol. 2011;60 doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar AJ. Genetic models of handedness, brain lateralization, schizophrenia, and manic-depression. Schizophr Res. 1999;39:207–218. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruuk LEB. Estimating genetic parameters in natural populations using the “animal model”. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2004;359:873–890. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laland KN, Kumm J, Van Horn JD, Feldman MW. A gene-culture model of human handedness. Behav Genet. 1995;25:433–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02253372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente M, Palou L, Carrasco L, Riba D, Mosquera M, Colell M, Fabre M, Feliu O. Population-level right handedness for a coordinated bimanual task in naturalistic housed chimpanzees: replication and extension in 114 animals from Zambia and Spain. Am J Primatol. 2010;71:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Walsh B. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. Sinauer; Sunderland, Mass: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeilage PF, Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G. Evolutionary origins of your right and left brain. Sci Am. 2009;301:60–67. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0709-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeilage PF, Studdert-Kennedy MG, Lindblom B. Primate handedness reconsidered. Behav Brain Sci. 1987;10:247–303. [Google Scholar]

- Manning JT, Heaton R, Chamberlain AT. Left-side cradling: similarities and differences between apes and humans. J Hum Evol. 1994;26:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC, Marchant LF. On the other hand: Current issues in and meta-analysis of the behavioral laterality of hand function in non-human primates. Yearb Phys Anthropol. 1997;40:201–232. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC, Marchant LF. Laterality of hand use pays off in foraging success for wild chimpazees. Primates. 1999;40:509–513. [Google Scholar]

- McManus IC, Bryden MP. The genetics of handedness, cerebral dominance and lateralization. In: Rapin I, Segalowitz SJ, editors. Handbook of neuropsychology. Vol 6. Developmental neuropsychology, Part 1. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1992. pp. 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Medland SE, Duffy DL, Wright MJ, Geffen GM, Hay DA, Levy F, van-Beijsterveldt CEM, Willimsen G, Townsend GC, White V, Hewitt AW, Mackey DA, Bailey JM, Slutske WS, Nyholt DR, Treloar SA, Martin NG, Boomsma DI. Genetic influences on handedness: Data from 25,732 Australian and Dutch twin families. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:33–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel GF. Right-handedness: A consequence of infant supine head-orientation preference? Science. 1981;212:685–687. doi: 10.1126/science.7221558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists. Biological Reviews. 2010;85:935–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelle IB, Ehrman L. An international study of human handedness : The data. Behav Genet. 1994;24:217–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01067189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M, Best N, Cowles K, Vines K. CODA: Convergence Diagnosis and Output Analysis for MCMC. R News. 2006;6:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Porac C, Coren S. Lateral preferences and human behavior. Springer; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Previc FH. A general theory concerning the prenatal origins of cerebral lateralization in humans. Psychological Review. 1991;98:299–334. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provins KA. Handedness and speech: A critical reappraisal of the role of genetic and environmental factors in the cerebral lateralization of function. Psychological Review. 1997;104:554–571. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond M, Pontier D. Is there geographical variation in human handedness? Laterality. 2004;9:35–51. doi: 10.1080/13576500244000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LJ, Andrew JR. Comparative vertebrate lateralization. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G, Andrew RJ. Divided brains: the biology and behaviour of brain asymmetries. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sicotte NL, Woods RP, Mazziotta JC. Handedness in twins: A meta-analysis. Laterality. 1999;4:265–286. doi: 10.1080/713754339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strockens F, Gunturkun O, Sebastian O. Limb preferences in non-human vertebrates. Laterality. doi: 10.1080/1357650X.2012.723008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uomini NT. The prehistory of handedness: Archeological data and comparative ethology. J Hum Evol. 2009;57:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallortigara G, Bisazza A. How ancient is brain lateralization? In: Rogers LJ, Andrew RJ, editors. Comparative vertebrate lateralization. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ. Survival with an asymmetrical brain: Advantages and disadvantages of cerebral lateralization. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28:574. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren D, Stern MM, Duggirala R, Dyer TD, Almasy L. Heritability and linkage analysis of hand, foot and eye preference in Mexican Americans. Laterality. 2012;11:508–524. doi: 10.1080/13576500600761056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JM. Handedness and laterality in humans and other animals. Physiological Psychology. 1980;8:351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AJ, Réale D, Clements MN, Morrissey MM, Postma E, Walling CA, Kruuk LEB, Nussey DH. An ecologist’s guide to the animal model. J Anim Ecol. 2009;79:13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo R, Thoma RJ, Gangestad SW. Human handedness: a biological perspective. In: Segalowitz SJ, Rapin I, editors. Handb Neuropsychol. Elsevier; London: 2002. pp. 329–364. [Google Scholar]