Abstract

Background

Since little is known as to whether sex differences affect the clinical presentation of pediatric BP-I disorder, it is an area of high clinical, scientific and public health relevance.

Methods

Subjects are 239 BP-I probands (65 female probands, 174 male probands) and their 726 first-degree relatives, and 136 non-bipolar, non-ADHD control probands (37 female probands, 99 male probands) and their 411 first-degree relatives matched for age and sex. We modeled the psychiatric and cognitive outcomes as a function of BP-I status, sex, and the BP-I status-gender interaction.

Results

BP-I disorder was equally familial in both sexes. With the exception of duration of mania (shorter in females) and number of depressive episodes (more in females), there were no other meaningful differences between the sexes in clinical correlates of BP-I disorder. With the exception of a significant sex effect for panic disorder and a trend for substance use disorders (p=0.05) with female probands being at a higher risk than male probands, patterns of comorbidity were similar between the sexes. Despite the similarities, boys with BP-I disorder received more intensive and costly academic services than girls with the same disorder.

Limitations

Since we studied children referred to a family study of bipolar disorder, our findings may not generalize to clinic settings.

Conclusions

We found more similarities than differences between the sexes in the personal and familial correlates of BP-I disorder. Clinicians should consider bipolar disorder in the differential diagnosis of both boys and girls afflicted with symptoms suggestive of this disorder.

Keywords: Bipolar, sex effects, family study

Introduction

Bipolar-I (BP-I) disorder in youth is increasingly recognized as a valid, prevalent and disabling disorder (Biederman et al., 1996, Faedda et al., 2004, Wozniak et al., 2011). Family and other studies document robust patterns of familiality (Schulze et al., 2006, Wozniak et al., 2010, Wozniak et al., 2012), a protracted course (Wozniak et al., 2011) and selective responsivity to antimanic agents (Smith et al., 2007, Correll et al., 2010, Liu et al., 2011). While it clearly affects both sexes, very few studies have addressed whether the sex of the proband influences the clinical presentation of pediatric bipolar disorder. While Biederman et al. (2004) and Geller et al. (2000) found that the clinical correlates of BP-I disorder were virtually identical in boys and girls, Duax et al. (2007) reported that girls presented with higher rates of depressed mood than boys.

Further understanding of whether sex differences are operant in the presentation of pediatric BP-I disorder is an area of high clinical, scientific and public health relevance. If differences in the clinical presentation of BP-I disorder were to be identified between the sexes it could lead to improved identification of BP-I disorder in affected girls. Considering the high morbidity and disability associated with pediatric BP-I disorder, such improved identification of afflicted girls will have important public health significance. From the scientific standpoint, if sex moderates the clinical presentation of pediatric BP-I, it could inform neurobiological studies of pediatric BP-I disorder.

The main aim of this study was to assess whether sex of the proband child moderates the clinical correlates of BP–I disorder. To this end we assessed differences in the clinical phenotype of pediatric BP-I disorder, patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, neuropsychological deficits and familiality with BP-I disorder in a large sample of well characterized youth of both sexes. Based on the literature, we hypothesized that BP-I disorder in youth will be similar in both sexes. To the best of our knowledge this study represents the most comprehensive assessment of sex differences in pediatric BP-I disorder.

Methods and Materials

As previously described (Wozniak et al., 2010), the sample consisted of BP-I youth 6–17 years of age of both sexes, ascertained through the Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology at the Massachusetts General Hospital based on the presence of a full DSM-IV diagnosis of BP-I disorder in the proband and their first degree relatives. Comparators were youth without ADHD or BP-I disorder of similar age and sex along with their first-degree relatives participating in ongoing studies in our program (Biederman et al., 1992, Biederman et al., 1999). All studies used the same assessment methodology regardless of the disorder used to classify probands as cases, with the exception that the BP-I probands underwent an additional clinical assessment by the lead author (J.W.) to verify the diagnosis of BP-I disorder.

We recruited 239 BP-I probands and their 726 first-degree relatives. From 522 probands participating in our case-control ADHD family studies we randomly selected 136 non-bipolar, non-ADHD control probands and their 411 first-degree relatives so that the age and sex distribution were similar to that of the BP-I probands. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the subcommittee for human subjects of our institution. After complete description of the study to the subjects, all subjects’ parents or guardians signed written informed consent forms and children older than 7 years of age signed age appropriate written assent forms.

Ascertainment Method

As previously described (Wozniak et al., 2010), BP-I probands were ascertained from our clinical service, referrals from local clinicians or self-referral in response to advertisements in the local media. All probands were ascertained blind to the diagnostic status of their relatives. Subjects were administered a phone screen reviewing symptoms of DSM-IV BP-I disorder and, if criteria were met, were scheduled for a face-to-face structured diagnostic interview. In addition to the structured diagnostic interview using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (KSADS), an expert clinician (J.W.) met with each potential proband and his or her parents for a clinical interview in order to confirm the diagnosis of BP-I disorder. We have published data on the convergence of these clinical interviews with our structured interview diagnosis on the first 69 cases; we reported a 97% agreement between the structured interview and clinical diagnosis in an analysis of 69 children (Wozniak et al., 2003). Controls were ascertained from out-patients referred for routine physical examinations to pediatric medical clinics. Screening procedures were similar to those described for the recruitment of the BP-I probands with the exception that they were required not to have either ADHD or BP-I disorder

Diagnostic Procedures

Psychiatric assessments of subjects younger than 18 years were made with the KSADS-E (epidemiologic version) (Orvaschel, 1994) and assessments of adult family members older than 18 years were made with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 1997) supplemented with modules from the KSADS-E to cover childhood disorders. Diagnoses were based on independent interviews with mothers and direct interviews with children older than 12 years of age. Data were combined such that endorsement of a diagnosis by either report resulted in a positive diagnosis.

Interviews with both the KSADS-E and SCID were conducted by extensively trained and supervised psychometricians with undergraduate degrees in psychology. The interviewers were blind to the subjects’ ascertainment status, ascertainment site, and data collected from other family members. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced clinicians diagnose subjects from audio-taped interviews made by the assessment staff. Based on 500 interviews, the median kappa coefficient between raters and clinicians was 0.99. For individual diagnoses the kappas were ADHD (0.88), conduct disorder (1.0), major depression (1.0), bipolar (0.95), separation anxiety (1.0), agoraphobia (1.0), panic (0.95), substance use disorder (1.0), and tics/Tourette’s (0.89). The median agreement between individual clinicians and the clinical review committee was 0.87 and for individual diagnoses was ADHD (1.0), conduct disorder (1.0), major depression (1.0), bipolar (0.78), separation anxiety (0.89), agoraphobia (0.80), panic (0.77), substance use disorder (1.0), and tics/Tourette’s (0.68).

Children and adolescents were diagnosed with BP-I disorder according to DSM-IV criteria. The interview assessed mania and depression separately. For a diagnosis of mania, the DSM-IV requires subjects to meet criterion A for a distinct period of extreme and persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood lasting at least 1 week, plus criterion B, manifested by three (four if the mood is irritable only) of seven symptoms during the period of mood disturbance. To ensure that the criterion B symptoms were concurrent with criterion A mood disturbance, subjects were directed to focus on the worst or most impairing episode of mood disturbance while being assessed for the presence of the confirmatory B criterion symptoms. That is, the subject was asked to consider the time during which the screen was at its worst for the purpose of determining whether the remaining symptoms were also evident at the same time as the screening item. Also recorded was the onset of first episode, the number of episodes, offset of last episode, and total duration of illness. Any subject meeting criteria for BP-II or BP-NOS was not included in this study. To gauge a distinct episode, our interviewers asked for ‘a distinct period (of at least 1 week) of extreme and persistently elevated, expansive or irritable mood’ and further required that the irritability endorsed in this module is ‘super’ and ‘extreme.’

Statistical Analysis

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed using ANOVA for continuous outcomes, Pearson’s χ2 for binary outcomes, and Kruskal Wallis for SES. The Kaplan-Meier cumulative failure function was used to calculate survival curves and cumulative, lifetime risk of BP-I in relatives. Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate the risk of BP-I disorder in relatives. Across all Cox models, we used robust estimates of variance to account for the non-independence of the sample resulting from the correlation between family members.

We modeled the psychiatric and cognitive outcomes as a function of BP-I status, sex, and the BP-I status-gender interaction. A significant interaction term indicates that the association between BP-I and the outcome differed by sex. If the interaction term was significant, we presented the main effect of BP-I separately by sex. If the interaction term was not significant, we removed it and reran the model with only the main effects of sex and BP-I status. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using linear regression and binary outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression. Ordered logistic regression was used to analyze the SAICA. In the case of small numbers, we used exact logistic regression. Due to the nature of the covariates, we were unable to include them in the exact logistic regression models. Therefore, after testing the interaction effect with exact logistic regression, we tested the main effects with linear and logistic regression including all covariates in the model.

Since no control proband had either psychosis or generalized anxiety disorder, we used a random number generator to choose one proband from each control group (female/male) to have psychosis and generalized anxiety disorder. For generalized anxiety disorder, the control probands who had the lowest random number from each control group were chosen and for psychosis, the control probands who had the highest random number were chosen. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. All tests were two-tailed, and our alpha level was set at 0.05 for all analyses, unless otherwise noted. We calculated all statistics using STATA, version 12.0.

Results

The BP-I sample included 239 probands (65 female probands, 174 male probands), with a mean age of 10.7 ± 3.0 (Table 1). The control sample included 136 probands (37 female probands, 99 male probands) with a mean age of 10.7 ± 3.3. Across these groups, we found a significant difference in age, race, and socioeconomic status (SES) with BP-I female probands being the oldest, female controls being the most ethnically diverse, and male controls having the highest socioeconomic status. As a result, familial risk analyses were adjusted for race, SES, and proband’s age.

Table 1.

Demographics (N=375)

| Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| BP-I | Control | BP-I | Control | |||

|

| ||||||

| N=65 | N=37 | N=174 | N=99 | Test statistic | p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Baseline age | 11.8 ± 3.6 | 10.7 ± 2.5 | 10.3 ± 3.1 | 10.7 ± 3.2 | F(3, 371)=3.51 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 61 (94) | 33 (90) | 163 (94) | 99 (100) | χ2(9)=28.6 | 0.001 |

| African American | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| More than 1 | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | (0) | (0) | ||

|

| ||||||

| SES* | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | χ2(3)=11.50 | 0.01 |

SES: socioeconomic status

Clinical Characteristics

As shown in Table 2, BP-I (mania) onset was significantly associated with sex with girls having a later onset of the disorder. With the exception of duration of mania and number of depression episodes, there were no other meaningful differences between the sexes in other clinical correlates of BP-I disorder including mania total symptom count, number of episodes of mania, associated impairment, percent affected with a mixed state, or order of onset of mania or depression. In the main effects model, BP-I was a significant predictor of treatment, but the interaction model provided no evidence that sex moderated the association between BP-I and type of treatment. With the exception of a significant difference in the frequency of the mania symptom ‘increase in sexual activity’ for females versus males (p=0.045), we found no other meaningful differences between the sexes in individual symptoms of mania (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Bipolar Disorder, Lifetime Comorbid Disorders, and Academic, Cognitive, and Global Functioning in Males and Females with BP-I Disorder (N=375)

| Female | Male | Statistical Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| BP-I | Control | BP-I | Control | ||||

|

| |||||||

| N=65 | N=37 | N=174 | N=99 | Gender Effect | BP-I Effect | Interaction | |

|

| |||||||

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| BP-I Onset | 7.8 ± 4.3 | n/a | 5.8 ± 3.2 | n/a | t=−2.4, p=0.02 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| BP-I Total Symptom Count | 5.9 ± 1.5 | n/a | 5.8 ± 1.1 | n/a | t=−0.2, p=0.9 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| BP-I Total Number of Episodes | 17.8 ± 35.3 | n/a | 22.9 ± 61.9 | n/a | t=1.4, p=0.2 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| Depression Number of Episodes | 10.2 ± 16.8 | n/a | 10.7 ± 23.2 | n/a | t=7.2, p<0.001 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Depression Duration | 3.8 ± 2.6 | n/a | 3.7 ± 2.7 | n/a | t=0.7, p=0.6 | ||

|

| |||||||

| BPD Duration | 3.8 ± 3.0 | n/a | 4.1 ± 3.1 | n/a | t=2.0, p=0.047 | ||

|

| |||||||

| BP-I Impairment | |||||||

| Minimum | 0 (0) | n/a | 0 (0) | n/a | z=−0.5, p=0.6 | n/a | n/a |

| Moderate | 18(28) | 61 (35) | |||||

| Severe | 47(72) | 113 (65) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Depression Impairment | |||||||

| Minimum | 0 (0) | n/a | 6 (3) | n/a | exact, p=0.4 | ||

| Moderate | 21(32) | 61 (35) | |||||

| Severe | 39(60) | 92 (53) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Mania Onset Before Depression† | 15 (27) N=56 |

n/a | 52 (37) N=141 |

n/a | z=1.4, p=0.2 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| Mixed State† | 52 (93) N=56 |

n/a | 128 (91) N=141 |

n/a | z=0.2, p=0.8 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| Treatment | |||||||

| None | 0 (0) | 15 (40) | 2 (1) | 25 (25) | z=0.9, p=0.4 | z=7.2, p<0.001 | ns‡ |

| Any Counseling | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 10 (6) | 11 (11) | |||

| Medication | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | |||

| Both Counseling and Medication | 30(46) | 0 (0) | 92 (53) | 0 (0) | |||

| Hospitalization | 27(42) | 0 (0) | 59 (34) | 0 (0) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Lifetime Comorbid Disorders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Major Depression | 56 (86) | 4 (11) | 141(81) | 5 (5) | z=−1.0, p=0.3 | z=10.7, p<0.001 | ns‡ |

|

| |||||||

| Psychosis | 18(28) | 1 (3) | 63 (36) | 1 (1) | z=1.5, p=0.1 | z=4.8, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Any SUD | 9 (14) | 0 (0) | 16 (9) | 1 (1) | z=2.0, p=0.05 | z=2.8, p=0.004 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Disruptive Disorders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Conduct Disorder | 29 (45) | 0 (0) | 76 (44) | 2 (2) | z=0.7, p=0.5 | z=5.4, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 60 (92) | 0 (0) | 155(89) | 8 (8) | z=0.4, p=0.7 | z=11.6, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| ADHD | 47 (72) | n/a | 144(83) | n/a | z=1.2, p=0.3 | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||||||

| Anxiety Disorders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Multiple Anxiety Disorders (≥2) | 43 (66) | 4 (11) | 120(69) | 3 (3) | z=.2, p=0.8 | z=8.9, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Avoidance Disorder | 11 (17) | 2 (5) | 31 (18) | 0 (0) | z=−0.4, p=0.7 | z=3.6, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Separation Anxiety Disorder | 36 (55) | 6 (16) | 104(60) | 4 (4) | n/a | n/a | z=2.2, p=.03 |

|

| |||||||

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | z=0.2, p=0.9 | z=1.2, p=0.3 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Agoraphobia | 23 (35) | 1 (3) | 68 (39) | 2 (2) | z=.7, p=0.5 | z=5.5, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Simple Phobia | 34 (52) | 3 (8) | 34 (52) | 5 (5) | z=−1.7, p=0.1 | z=6.6, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Social Phobia | 23 (35) | 2 (5) | 60 (34) | 1 (1) | z=−.3, p=0.8 | z=5.2, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Panic Disorder | 14 (22) | 1 (3) | 19 (11) | 0 (0) | z=−2.3, p=0.02 | z=3.1, p=0.002 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 29 (45) | 1 (3) | 82 (47) | 1 (1) | z=0.7, p=0.5 | z=5.8, p<0.001 | Ns |

|

| |||||||

| Academic Functioning | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Repeated grade | 5 (8) | 2 (5) | 27(16) | 0 (0) | z=2.3, p=0.02 | z=1.0, p=0.3 | ns‡ |

|

| |||||||

| Special Class | 14 22) | 1 (3) | 73(42) | 2 (2) | z=3.1, p=0.002 | z=5.4, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Extra Help | 60(92) | 0 (0) | 155(89) | 8 (8) | z=2.0, p=0.04 | z=7.6, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Cognitive Functioning | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Vocabulary SS§ | 11.1 ± 3.0 | 11.6 ± 2.7 | 10.4 ± 3.4 | 13 ± 2.7 | n/a | n/a | t=−2.6, p=0.01 |

|

| |||||||

| Digit Span SS | 9.7 ± 2.6 | 10.5 ± 3.0 | 9.1 ± 2.8 | 10.8 ± 2.7 | t=−0.8, p=0.4 | t=−4.3, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Oral arithmetic SS | 11.9 ± 3.0 | 10.2 ± 3.0 | 9.6 ± 3.1 | 12.2 ± 2.8 | t=−0.7, p=0.5 | t=−6.7, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Digit symbol SS | 7.9 ± 3.5 | 12.5 ± 2.6 | 6.8 ± 3.4 | 11.9 ± 2.6 | t=−2.8 p=0.005 | t=−13.7, p<0.001 | ns |

|

| |||||||

| Full Scale IQ | 103.4 ± 13.2 | 109.2 ± 12.1 | 101.8 ± 14.3 | 118.2 ± 10.3 | n/a | n/a | t=−3.2, p<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Global Functioning | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| GAF Score | 40.6 ± 6.2 | 67.6 ± 6.0 | 40.8 ± 5.7 | 71.6 ± 9.0 | n/a | n/a | t368=−2.8, p<0.01 |

9 Female BP-I probands and 33 Male BP-I probands did not have a diagnosis of Depression. Among probands with both Mania and Depression (N=197), 21 (38%) Female BP-I probands and 51 (36%) Male BP-I probands had the same age of onset for Mania and Depression

ns=Not Significant. Interaction term is not significant. Removed from the model and it was rerun with only the main effects of gender and BP-I status.

SS=Scaled Score

Figure 1.

Mania Symptoms in Male and Female Probands (N=199)

Patterns of Psychiatry Comorbidity

Because we found a significant sex-by-BP-I interaction for separation anxiety disorder (p=0.03, Table 2, we ran additional models on this outcome separately for each sex. This analysis showed that in both female (N=102) and male probands (N=273), BP-I was significantly associated with separation anxiety disorder (z=3.8, p<0.001; z=6.5, p<0.001, respectively). Since there were no other significant interaction effects for all other psychiatric disorders assessed, we examined the main effects of sex and BP-I disorder without the interaction term. As shown in Table 2, BP-I was significantly associated with almost every psychiatric disorder assessed. However, with the exception of a significant sex effect for panic disorder and a trend for substance use disorders (p=0.05) with female probands being at a higher risk than male probands, no other sex effects were identified.

Functional Outcomes

As shown in Table 2, the analysis of sex-by-BP-I interactions predicting measures of academic function failed to yield any statistically significant results. In the main effects model, BP-I was significantly associated with lifetime histories of attending a special class and receiving extra help. Also, sex was significantly associated with lifetime histories of repeating a grade and attending a special class with male subjects being more likely to have experienced these academic difficulties. Females were more likely to receive extra help.

We found significant sex-by-BP-I interactions for vocabulary scaled score, full scale IQ, and lifetime GAF score. Within females, BP-I was significantly associated with a lower GAF score (t=−22.6, p<0.001). Within males, BP-I was significant associated with a lower: vocabulary scaled score (t=−5.6, p<0.001), full scale IQ (t=−9.0, p<0.001), and GAF score (t=−34.7, p<0.001). In the main effect models, BP-I disorder was significantly associated with the digit symbol scaled score (t=−4.8, p<0.001), the oral arithmetic scaled score (t=−6.7, p<0.001), and the digit span scaled score (t=−4.3, p<0.001). Sex was significantly associated with the digit symbol scaled score (t=−1.1, p=0.005) with girls having higher scores.

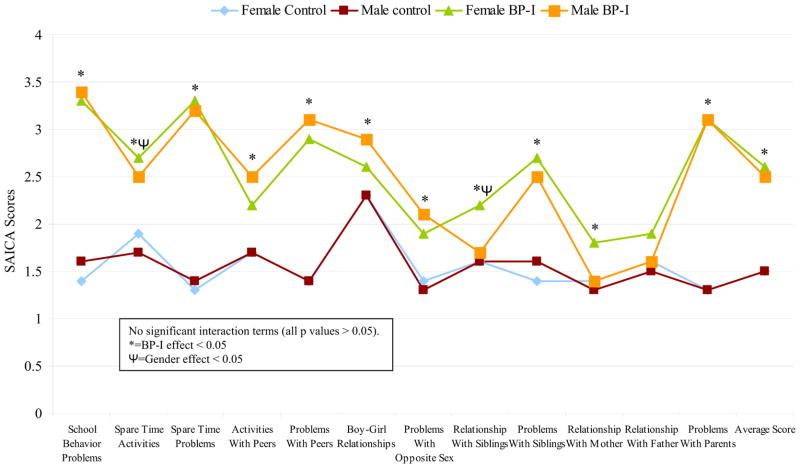

Social Environment and CBCL Findings

The interaction models provided no evidence that sex moderated the association between BP-I and items of the SAICA (all p values > 0.05; Figure 2). In the main effects model, BP-I was significantly associated with almost every item on the scale, including school behavior problems (z=19.5, p<0.001), problems with siblings (z=7.6, p<0.001), and problems with parents (z=10.9, p<0.001). Also, we found a significant sex effect for spare time activities (z=−2.7, p=0.008) with boys being less likely to be involved and being more likely to have a poor relationship with siblings (z=−2.2, p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Social Environment and Behavior - Social Adjustment Inventory for Children (SAICA) (N=251)

For the CBCL, the interaction models provided no evidence that sex moderated the associated between BP-I and the scales of the CBCL (all p values > 0.05; Figure 3A). In the main effects model, BP-I was significantly associated with the Aggression Scale (t=24.1, p<0.001), the Delinquent Behavior Scale (t=14.8, p<0.001), the Attention Scale (t=20.7, p<0.001), the Thought Problems Scale (t=21.1, p<0.001), the Social Complaints Scale (t=15.8, p<0.001), the Anxious/Depressed Scale (t=17.5, p<0.001), the Somatic Scale (t=11.3, p<0.001) and the Withdrawn Scale (t=13.1, p<0.001). Sex was significantly associated with the Thought Problems Scale with boys having more problems with thought (t=−2.1, p=0.04). We found no other significant effects of sex. We also examined whether sex effects were operant for the CBCL-Severe Dysregulation Profile (elevation (2 SDs) on Anxiety/Depression, Aggression, and Attention (A-A-A) scales). The interaction model provided no evidence that sex moderated the association between BP-I and the Severe Dysregulation Profile (z=−1.3, p=0.2) (Figure 3B). For the main effect models, BP-I was significantly associated with having a positive profile (z=5.0, p<0.001) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Familial Risk Analysis

The interaction model provided no evidence that sex moderated the familial risk of BP-I (z=−0.7, p=0.51). As shown in Figure 4, BP-I disorder in probands was a significant predictor of BP-I in relatives irrespective of sex of the proband.

Figure 4.

Familial risk of Bipolar-I (BP-I) Disorder in First-Degree Relatives Stratified by Proband Sex

Discussion

In this large, controlled study examining sex effects in a large sample of referred youth with BP-I disorder, we found more similarities than differences between the sexes in the personal and familial correlates of BP-I disorder. These findings confirm results from a previous report from our group examining sex differences in a separate clinic sample of youth with BP-I disorder youth (Biederman et al., 2004). As in this previous report, our data finds that both males and females with BP-I disorder have high levels of severe irritability, predominantly mixed presentations, and high levels of comorbidity with disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and substance use disorders. In addition, both groups had highly impaired interpersonal deficits as assessed through scores on the SAICA and a wide range of emotional functioning deficits as assessed through the CBCL.

Our results are also strongly consistent with those of Geller et al. (Geller et al., 2000) that also failed to find sex differences in the clinical features of pediatric BP-I disorder. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that pediatric BP-I disorder is a highly impairing disorder with similar clinical manifestations in both sexes.

Despite striking similarities in the clinical correlates of pediatric BP-I disorder between the sexes, there were a few noteworthy differences between the sexes as well. Girls had a significantly later age of onset of mania than boys, a significantly higher rate of panic disorder than boys, and although not reaching our a priori threshold for statistical significance, girls had a higher rate of substance use disorders. They also had a significantly higher rate of hypersexuality than boys (60% vs. 42%). While these findings could have been due, by chance, to the many comparisons conducted, and more work will be needed to confirm them, they open some intriguing possibilities.

A later age of onset of symptoms of mania in girls and the higher risk for panic attacks could result in delays and confusion in the diagnosis of BP-I disorder in afflicted girls. We also found that girls with BP-I disorder were referred for treatment on average one year later than boys (11.8 years versus 10.3 years) suggesting delays in the identification and treatment of girls with BP-I disorder relative to boys with the same disorder. Considering the morbidity and disability associated with pediatric BP-I disorder, these findings could have very adverse consequences for girls with this disorder.

The statistically significant higher rate, of hypersexuality in girls with BP-I disorder relative to boys with this disorder is also noteworthy. Hypersexuality when coupled with the recklessness and poor judgment of BP-I disorder can result in increased vulnerability to traumatic experiences, further complicating an already compromised developmental course of this highly morbid disorder. The co-occurrence of traumatic experiences could also lead clinicians to mistake the symptoms of mania in some of these youth for PTSD when indeed either the opposite could be the case or more likely, both mania and PTSD could be simultaneously present. Hypersexuality is additionally of great clinical concern given the young age of the sample, suggesting a precocious interest in adult matters, which could place such children seriously in harm’s way.

Consistent with the extant literature on pediatric BP-I disorder (Biederman et al., 2004), both males and females presented with equally high levels of severe irritability and mixed states that were observed in over 80% of the boys and girls in this sample. Mania-associated irritability is extremely severe and often the main focus of the chief complaint in clinical settings, and can result in need for psychiatric hospitalization or criminal arrest. Likewise, mixed states represent a particularly severe form of BP-I disorder associated with high levels of morbidity and disability (McElroy et al., 1992). It is noteworthy that no sex differences were observed in other symptoms of mania, including euphoria and grandiosity, suggested by some researchers to represent ‘cardinal symptoms’ of mania (Geller and Tillman, 2005, Wozniak et al., 2005).

With the exception of a slightly lower number of depressive episodes in girls than in boys, there were no other meaningful differences in the clinical correlates of depression between boys and girls. This finding differs from a previous report (Duax et al., 2007) which suggested that girls with BP-I disorder spend more time depressed than manic than males with this disorder. More work is needed to help resolve these discrepant findings.

Both male and female probands presented with similar and high levels of lifetime comorbid psychiatric conditions including ADHD (83% versus 72%) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (89% versus 92%). Likewise, both sexes suffered from similar and high rates of psychosis (36% versus 28%) and anxiety disorders (69% versus 66%) (with the exception of panic disorder which was higher in females than in males). Despite their young age, boys and girls with BP-I disorder already started manifesting a similar increased risk for substance use disorders (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence), a well known complication of pediatric BP-I disorders (Wilens et al., 1999, Wilens et al., 2004), with a trend (p=0.05) for higher rate in girls versus boys (14% versus 9%).

Both sexes with BP-I disorder showed highly impaired scores on the SAICA and the CBCL demonstrating equally severe levels of psychosocial and emotional dysfunction. Likewise, both boys and girls with BP-I disorder had high rates of the CBCL-Severe Dysregulation profile characterized by marked elevations (2SDs) of the CBCL Attention, Anxiety/Depression and Aggression scales, previously linked to a clinical diagnosis of pediatric BP-I disorder. These results support the utility of the CBCL-Severe Dysregulation profile to identify youth at risk for BP-I disorder in both sexes (Biederman et al., 2012).

While girls with BP-I were more likely to receive extra academic help than boys with BP-I disorder, rates in both sexes were very high (92% and 89%). Notably, boys with BP-I disorder were twice as likely as girls with BP-I to repeat a grade (16% versus 8%) and be placed in a special class (42% versus 22%), suggesting that boys with bipolar disorder receive more intensive and costly academic services than girls with the same disorder. Given the many other similarities in symptom profile, clinical picture, rating scale scores and cognitive functioning, the reason for this remains unclear and might represent a difference in the manifestation of symptoms in the school arena or a bias against retaining girls or placing them in separate classes.

BP-I disorder was equally familial in both sexes indicating that sex does not moderate the familial risk for BP-I disorder in first degree relatives in probands with pediatric BP-I disorder. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report examining sex effects of familiality of pediatric BP-I disorder. This finding is particularly noteworthy considering that familiality is a useful external validator of complicated diagnostic entities such as pediatric BP-I disorder (Wozniak et al., 2012).

Our findings should be evaluated in light of methodological limitations. Although raters administering the structured interviews were highly selected, trained and supervised, they were not clinicians. All structured interviews of children under age 12 were only done with a parent about the child; only children older than age 12 were also interviewed directly with structured interviews. Although children may not be accurate reporters of lifetime psychopathology (Wozniak et al., 2003), some information may be lost by not directly interviewing the children under age 12 with structured interview, although this would represent an error of omission rather than commission. Mitigating against concerns that this might affect the accuracy of the diagnosis of mania, the principal investigator clinically confirmed the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in all probands via a clinical meeting with the child and parent(s). Since we studied children referred to a family study of bipolar disorder, our findings may not generalize to clinic settings. More work is needed with large samples of general clinic referrals and via epidemiological studies.

Despite these limitations we found that in both sexes, the clinical presentation of BP-I disorder includes very high rates of severe irritability, hypersexuality, mixed states, high rates of comorbidity with disruptive disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, high levels of interpersonal and neuropsychological deficits, as well as high levels of familiality with BP-I disorder in first degree relatives. This work is a true replication of similar findings reported in a separate clinic sample (Biederman et al., 2004) as well as a research sample from a separate site (Geller et al., 2006). This work indicates that the highly impairing clinical picture of pediatric BP-I manifests itself similarly in both sexes and should encourage clinicians to consider this diagnosis in both sexes.

Acknowledgments

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Janet Wozniak MD is a speaker for Primedia/MGH Psychiatry Academy, and receives research support from McNeil, Shire, Janssen, and Johnson & Johnson. Her spouse, John Winkelman MD, PhD, is a consultant/advisory board for Impax Laboratories, Pfizer, UCB, Zeo Inc., Sunovion, and receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: Elminda, Janssen, McNeil, and Shire. In 2012, Dr. Joseph Biederman received an honorarium from the MGH Psychiatry Academy and The Children’s Hospital of Southwest Florida/Lee Memorial Health System for tuition-funded CME courses. In 2011, Dr. Joseph Biederman gave a single unpaid talk for Juste Pharmaceutical Spain, received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course, and received an honorarium for presenting at an international scientific conference on ADHD. He also received an honorarium from Cambridge University Press for a chapter publication. Dr. Biederman received departmental royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Eli Lilly, Shire and AstraZeneca; these royalties are paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH. In 2010, Dr. Joseph Biederman received a speaker’s fee from a single talk given at Fundación Dr. Manuel Camelo A.C. in Monterrey Mexico. Dr. Biederman provided single consultations for Shionogi Pharma Inc. and Cipher Pharmaceuticals Inc.; the honoraria for these consultations were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at the MGH. Dr. Biederman received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course. In previous years, Dr. Joseph Biederman received research support, consultation fees, or speaker’s fees for/from the following additional sources: Abbott, Alza, AstraZeneca, Boston University, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltech, Cephalon, Eli Lilly and Co., Esai, Fundacion Areces (Spain), Forest, Glaxo, Gliatech, Hastings Center, Janssen, McNeil, Medice Pharmaceuticals (Germany), Merck, MMC Pediatric, NARSAD, NIDA, New River, NICHD, NIMH, Novartis, Noven, Neurosearch, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Phase V Communications, Physicians Academy, The Prechter Foundation, Quantia Communications, Reed Exhibitions, Shire, the Spanish Child Psychiatry Association, The Stanley Foundation, UCB Pharma Inc., Veritas, and Wyeth.

In the past year, Dr. Faraone received consulting income and/or research support from Shire, Otsuka and Alcobra and research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He is also on the Clinical Advisory Board for Akili Interactive Labs. In previous years, he received consulting fees or was on Advisory Boards or participated in continuing medical education programs sponsored by: Shire, McNeil, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. Dr. Faraone receives royalties from books published by Guilford Press: Straight Talk about Your Child’s Mental Health and Oxford University Press: Schizophrenia: The Facts.

MaryKate Martelon, Mariely Hernandez, and K. Yvonne Woodworth report no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTORS

Dr. Wozniak had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Wozniak substantially contributed to the conception and design, drafting, critical revision of the intellectual content, supervision, administrative/technical/material support, and funding for this manuscript. Dr. Biederman substantially contributed to the conception and design, drafting, critical revision of the intellectual content, administrative/technical/material support, and supervision for this manuscript. Ms. Martelon substantially contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, drafting, and statistical analysis for this manuscript. Ms. Hernandez substantially contributed to the drafting, critical revision of the intellectual content, and administrative/technical/material support for this manuscript. Ms. Woodworth substantially contributed to the drafting, critical revision of the intellectual content, and administrative/technical/material support for this manuscript. Dr. Faraone substantially contributed to the conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the intellection content, and statistical analysis for this manuscript. All authors have contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Benjamin J, Krifcher B, Moore C, Sprich-Buckminster S, Ugaglia K, Jellinek MS, Steingard R, Spencer T, Norman D, Kolodny R, Kraus I, Perrin J, Keller MB, Tsuang MT. Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives in psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:728–738. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Wozniak J. Mania in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;34:1257–1258. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Williamson S, Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Weber W, Jetton J, Kraus I, Pert J, Zallen B. Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:966–975. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Kwon A, Wozniak J, Mick E, Markowitz S, Fazio V, Faraone SV. Absence of gender differences in pediatric bipolar disorder: Findings from a large sample of referred youth. J Affect Disord. 2004;83:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Day H, Goldin RL, Spencer T, Faraone SV, Surman CB, Wozniak J. Severity of the aggression/anxiety-depression/attention child behavior checklist profile discriminates between different levels of deficits in emotional regulation in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:236–243. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182475267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Sheridan EM, Delbello MP. Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: a comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:116–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duax JM, Youngstrom EA, Calabrese JR, Findling RL. Sex differences in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1565–1573. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ, Glovinsky IP, Austin NB. Pediatric bipolar disorder: phenomenology and course of illness. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:305. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Delbello MP, Soutullo CA. Diagnostic characteristics of 93 cases of a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype by gender, puberty and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000;10:157–164. doi: 10.1089/10445460050167269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R. Prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar I disorder: review of diagnostic validation by Robins and Guze criteria. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 7):21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B, Strauss NA, Kaufmann P. Controlled, blindly rated, direct-interview family study of a prepubertal and early-adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype: morbid risk, age at onset, and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1130–1138. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HY, Potter MP, Woodworth KY, Yorks DM, Petty CR, Wozniak JR, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Pharmacologic treatments for pediatric bipolar disorder: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:749–762. e739. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcelroy SL, Keck J, Pope PE, JHG, Hudson JI, Faedda G, Swann AC. Clinical and research implications of the diagnosis of dysphoric or mixed mania or hypomania. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1633–1644. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version. Nova Southeastern University, Center for Psychological Studies; Ft. Lauderdale: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze TG, Hedeker D, Zandi P, Rietschel M, Mcmahon FJ. What is familial about familial bipolar disorder? Resemblance among relatives across a broad spectrum of phenotypic characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1368–1376. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, Taylor D. Pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar mania: a systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:551–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens T, Biederman J, Millstein R, Wozniak J, Hahsey A, Spencer T. Risk for substance use disorders in youths with child- and adolescent-onset bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:680–685. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens T, Biederman J, Kwon A, Ditterline J, Forkner P, Chase R, Moore H, Swezey A, Snyder L, Morris M, Henin A, Wozniak J, Faraone SV. Risk for substance use disorders in adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1380–1386. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000140454.89323.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Monuteaux M, Richards J, Lail K, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Convergence between structured diagnostic interviews and clinical assessment on the diagnosis of pediatric-onset bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:938–944. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kwon A, Mick E, Faraone S, Orlovsky K, Schnare L, Cargol C, Van Grondelle A. How cardinal are cardinal symptoms in pediatric bipolar disorder? An examination of clinical correlates. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Monuteaux M, Coville A, Biederman J. A controlled family study of children with DSM-IV bipolar-I disorder and psychiatric co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1079–1088. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Petty CR, Schreck M, Moses A, Faraone SV, Biederman J. High level of persistence of pediatric bipolar-I disorder from childhood onto adolescent years: a four year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Martelon M, Mckillop H, Biederman J. Further evidence for robust familiality of pediatric bipolar I disorder: results from a very large controlled family study of pediatric bipolar I disorder and a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1328–1334. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]