Abstract

Objective

Rheumatoid arthritis is a sexually dimorphic inflammatory autoimmune disease with both articular and extra-articular disease manifestations including rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD). Low levels of testosterone have been linked to disease severity in men with rheumatoid arthritis and supplemental testosterone has been shown to improve symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis in both postmenopausal women and men with low testosterone. The mechanisms by which sex and sex steroids affect the immune system and autoimmunity are poorly understood. In this study we examined the protective effect of testicular-derived sex hormones on both joint and lung disease development in an autoimmune mouse model.

Methods

Arthritis prevalence and severity were assessed in female, orchiectomized, sham orchiectomized, and intact male SKG mice over a 12 week period after intraperitoneal injection of zymosan. Lung tissues were evaluated by quantifying: cellular accumulation in bronchoalveolar lavage, collagen levels, and histology. An antigen microarray was used to evaluate autoantibody generation in each condition.

Results

Female SKG mice developed arthritis and lung disease with increased prevalence and severity when compared to intact male mice. The absence of testosterone after orchiectomy led to increased arthritis, lung disease and autoantibody generation in orchiectomized male mice compared to intact male mice.

Conclusions

SKG mice represent an authentic sexually dimorphic mouse model of both the joint and lung disease seen in rheumatoid arthritis. Testosterone protects against the development of joint and lung disease in male SKG mice.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic disease with both articular and extra-articular disease manifestations that preferentially affects women (1). Because of the predominance of autoimmunity in women, the role of estrogen in immunity and autoimmunity has been studied much more extensively than that of testosterone. Estrogen has been shown to influence T- and B-cell maturation and to promote a Th2 CD4+ T-cell phenotype which can lead to increased antibody production by plasma cells (as reviewed by (2)). Male sex hormones have been shown to play an important role in immune regulation as well, and may contribute to the sex differences seen in RA. For example, testosterone inhibits the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ from stimulated human peripheral blood leukocytes (3). Macrophages from orchiectomized mice have higher cell surface expression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR 4) rendering the mice more susceptible to endotoxic shock compared to intact counterparts (4). Cross-sectional patient analysis indicates that men with RA have a lower mean serum testosterone level compared to healthy men (5). Such cross-sectional studies are limited in that they cannot determine if low testosterone reflects a primary risk factor for disease development, an effect of inflammation, or the disease process itself. Taken together, these and other studies suggest that testosterone may have an important immunoregulatory role in autoimmune diseases such as RA.

Extra-articular disease manifestations, including pulmonary disease, are an important source of morbidity and mortality in patients with RA. Progressive rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) occurs in nearly 10% of RA patients and is associated with significantly reduced survival (6). Little is known about the mechanisms by which lung disease develops in the context of RA and even less is known about the role of sex hormones in disease development. To address this issue, we studied the role of testicular-derived sex hormones on the development of arthritis, interstitial pneumonia and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) in SKG mice. As we will show, female SKG mice develop arthritis and interstitial pneumonia with more rapid onset and with increased prevalence and severity compared to male SKG mice. Using a surgical orchiectomy approach, we prospectively investigated the effect of testosterone on the development of arthritis, interstitial lung disease and autoantibody formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

SKG mice were maintained in a specific pathogen free environment in our animal colony. All experiments were approved by the National Jewish Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgical orchiectomy and measurement of testosterone

Anesthetized and surgically prepared male mice (4–6 weeks) were placed in dorsal recumbency. 1–2 cm ventral midline incisions were made at the scrotum and the skin was retracted to expose the tunica. The tunica was pierced and the testes were pushed out one at a time. The testes were raised to expose the underlying blood vessels and tubules. The testes were removed using forceps to pull off each testicle; any minor bleeding was controlled by direct pressure using forceps. All deferential vessels and ducts were replaced back into the tunica. Skin incisions were closed with stainless steel wound clips (removed after 7–10 days) or absorbable suture material. Sham surgical orchiectomy with and without testicular manipulation was performed resulting in universally reduced testosterone levels. Additional sham surgery at a remote site located on the dorsum of the mice also resulted in reduced testosterone levels. Therefore sham orchiectomy was determined to be an inappropriate control for surgical intervention alone.

Serum testosterone levels were measured prior to surgery and at 12 weeks post zymosan or saline injection using a commercially available testosterone ELISA kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

Induction of arthritis and pulmonary disease

All mice (8–12 weeks) were given a single intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg of zymosan (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to induce arthritis and lung disease as previously described (7). Control mice were injected with saline. Arthritis scores were determined weekly as previously described (7).

Determination of lung disease

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells were obtained and assessed as previously described (7). The left lung was inflated with 10% neutral buffered formalin at a pressure of 20 cm H2O, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 μm sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For stereologic examination, lung tissue was cut into 2 mm sections and randomly arranged into paraffin blocks. Sections were cut at 5 μm intervals. Three slides per mouse were examined with a total of 15 images captured at 10X in a blinded manner on an Olympus BX51 microscope. Quantitative analysis was performed using stereology grid-counting techniques to assess areas of disease, as previously described (7). All coefficients of error values were calculated at less than p<0.05 (7). Representative images were obtained from mice with the median stereology score from each of the zymosan-injected groups. To determine lung collagen content, the right upper lobe was homogenized in PBS and incubated overnight with an equal volume of 12N HCl at 120°C. Lung collagen levels were evaluated by quantifying hydroxyproline as previously described (7).

Antigen Array

Bead-based antigen arrays were used to characterize a panel of serum autoantibodies, as previously described (8). Briefly, 43 putative RA-associated autoantigens were conjugated to spectrally-distinct beads (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and mixed with diluted mouse serum. After washing, beads were incubated with PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody and after another series of washes, the bead mixture was passed through a laser detector (Luminex 200) that identifies beads based on dye fluorescence. The amount of antibody bound to each bead was determined by fluorescence intensity.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between data points were examined using an unpaired t test with Welch’s correction or a One-way Analysis of Variance with a Neuman-Keuls multiple comparison test. Antigen array data was analyzed using Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM; version 3.08) to identify autoantibody reactivities that exhibited significant differences between intact males, orchiectomized males, and female zymosan-treated SKG mice. The antigen array reactivities for each mouse were arranged using hierarchical cluster analysis (Cluster 3.0 software) and displayed as a heatmap (Java TreeView software version 1.1.3).

RESULTS

Arthritis in SKG mice is sexually dimorphic and the absence of testosterone increases the prevalence and severity of arthritis

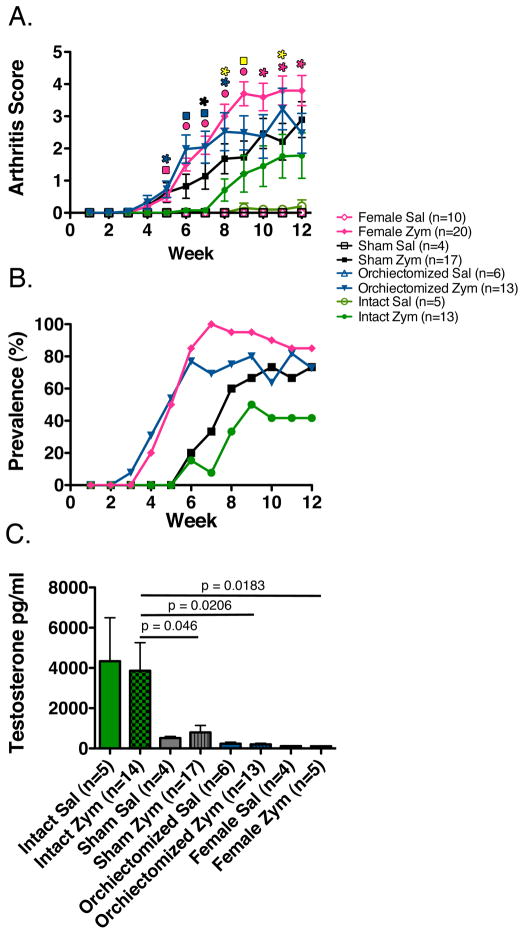

To investigate how testosterone affects the development of arthritis, male SKG mice were either surgically orchiectomized, left intact, or underwent a sham surgical procedure. After full recovery from surgery, sham and orchiectomized mice as well as intact male and female mice were intraperitoneally injected with 5 mg of zymosan or saline as a control. Female SKG mice developed arthritis with increased severity and prevalence when compared to their intact male counterparts (Figure 1A and B). Surgical orchiectomy of male mice, confirmed by low serum testosterone levels (Figure 1C), resulted in increased arthritis severity and prevalence compared to intact mice (Figure 1A and B). There was no significant difference between the severity of arthritis in female and orchiectomized male mice (p > 0.17). Interestingly sham surgical procedure at the testes both with and without testicular manipulation, as well as a surgical procedure at a remote site on the dorsum of the mice, resulted in low testosterone levels that were not statistically different from female or castrated mice (Figure 1C). Mice that received a sham surgical procedure developed arthritis that was not statistically different from either castrated or intact male mice (Figure 1A). However, they develop significantly less arthritis than female mice at later time points (Figure 1A)

FIGURE 1. Arthritis development in SKG mice is sexually dimorphic and is decreased in the presence of testicular-derived sex hormones.

(A) Arthritis scores reveal increased arthritis severity in female and orchiectomized mice compared to intact male control mice (*p <0.5, square p <0.01, circle p <0.001). Blue represents orchiectomized mice versus intact male mice, pink female mice versus intact male mice, black sham surgical mice versus intact male mice, and yellow sham surgical mice versus female mice. There was no difference in arthritis severity between female and orchiectomized mice at any time point. (B) Female and orchiectomized mice developed arthritis with increased prevalence when compared to intact male control mice. (C) Testosterone levels were significantly increased in intact mice compared to orchiectomized, sham surgical, and female mice. (sal = saline-injected, zym = zymosan-injected)

Testosterone protects against the development of interstitial lung disease

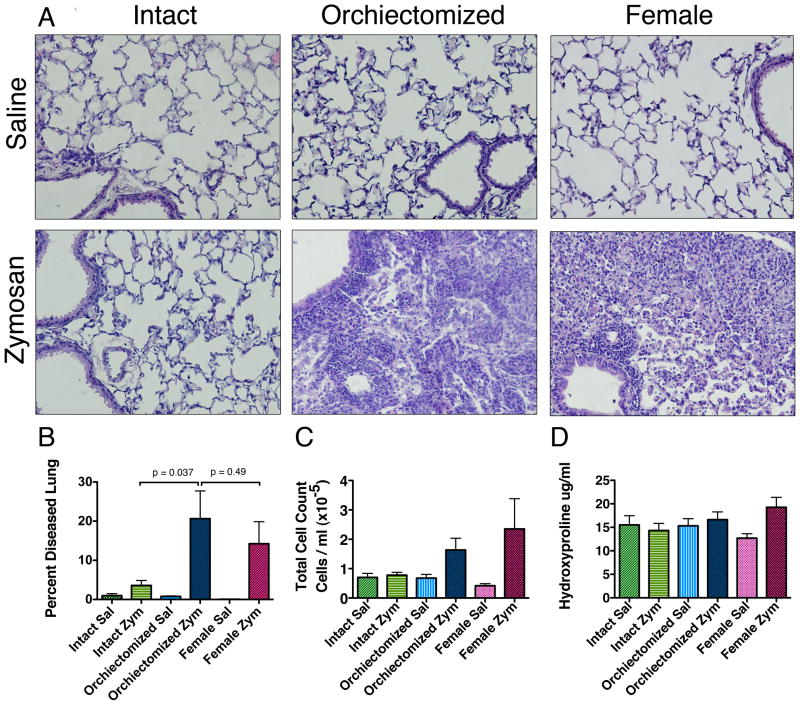

We next investigated how testosterone affects the development of lung disease in female, intact male, and orchiectomized male mice. Given the lack of significant difference in arthritis prevalence and severity or testosterone between sham surgical and orchiectomized mice we did not include sham surgical mice in further analysis. At 12 weeks, the lung disease in female and orchiectomized male zymosan-injected SKG mice was characterized by patchy subpleural and peribronchovascular mixed inflammation compared to normal lung and saline controls (Figure 2A). At higher magnification, severe infiltration of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes within alveolar septae and airspaces was observed (Figure 2A). There were very few areas of disease identified in the lung tissue of the zymosan-injected intact male mice.

FIGURE 2. Lung disease development in SKG mice is sexually dimorphic and is decreased in the presence of testicular-derived sex hormones.

(A) Saline-injected mice demonstrate normal lung architecture by H&E staining (20x). Lungs from zymosan-injected orchiectomized and female SKG mice demonstrate mixed peribronchoalveolar inflammation rich in macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes by H&E staining (20x). (B) Zymosan-injected orchiectomized SKG mice had an increase in the percent of diseased lung compared to intact zymosan-injected males. There was no significant difference between the percent of diseased in orchiectomized zymosan-injected mice compared to zymosan-injected females (p <0.05). (C) Bronchoalveolar lavage 12 weeks after zymosan injection showed a non-significant trend toward increased airspace cells in orchiectomized male and female mice compared to intact male zymosan-injected mice. (Intact sal n=4, Intact zym n=7, Orchiectomized sal n=4, Orchiectomized zym n=12, Female sal n=10, Female zym n=20). (D) There was no significant increase in the collagen content of the lung determined by hydroxyproline. (sal = saline-injected, zym = zymosan-injected)

Using quantitative stereologic techniques we evaluated the penetrance and extent of lung disease involvement in female, orchiectomized male, and intact male mice. There was a statistically significant increase in the degree of lung disease in the female and orchiectomized male mice compared to saline controls (p<0.05, Figure 2B). There was no increase in the amount of lung disease seen in the intact males compared to saline controls (p=0.15, Figure 2B). However, there was a significant increase in the amount of lung disease in the zymosan-injected orchiectomized males compared to zymosan-injected intact males (p<0.05, Figure 2B). There was no significant difference between the amount of lung disease in zymosan-injected orchiectomized male mice and zymosan-injected female mice. Bronchoalveolar lavage 12 weeks after zymosan injection showed a non-significant trend toward increased airspace inflammatory cells in orchiectomized male and female mice compared to intact zymosan-injected male mice (p=0.49, Figure 2C). There was no difference in the numbers of macrophages, lymphocytes or neutrophils between the groups of zymosan-injected mice. There was no evidence of significant collagen deposition as measured by hydroxyproline (Figure 2D).

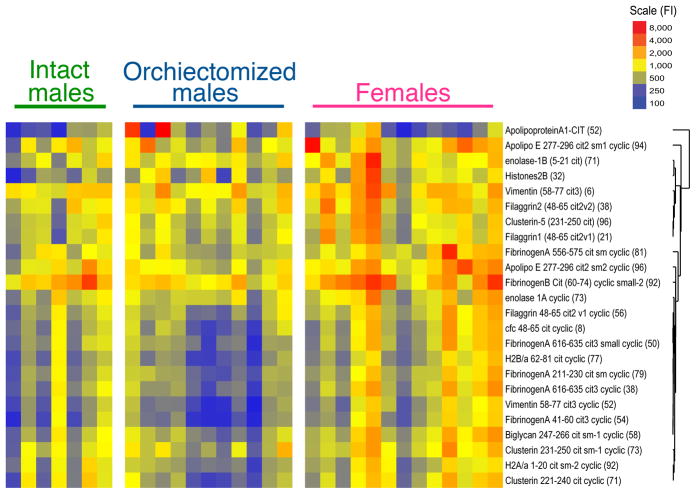

The absence of testosterone results in increased production of antibodies to citrullinated peptides

Finally, we investigated how testosterone affects the development of ACPA in female, intact, and orchiectomized zymosan-treated mice. At 12 weeks, there was an increase in the level of 24 (of 43 total evaluated) autoantibodies in female and orchiectomized male mice (q < 5.2 %, Figure 3). Multiclass Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) analysis revealed highly different ACPA levels across all three groups with highest levels of these ACPA in female mice followed by orchiectomized mice and lowest levels in intact male mice. Increased reactivity to a broad range of citrullinated antigens was noted including those derived from fibrinogen, vimentin, enolase, histone 2B, clusterin, biglycan, apolipoproteins A and E, as well as fillagrin. No increased reactivity was noted among non-citrullinated control antigens including native fibrinogen and vimentin. Included among the highly targeted antigens are several proteins which are themselves toll-like receptor agonists including fibrinogen, biglycan, and histone 2B (9, 10), suggesting that orchiectomy may enhance inflammation through both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms.

FIGURE 3. SKG disease associated with production of antibodies to citrullinated peptides.

Multiclass Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) analysis revealed an increase in the level of 24 (of 43 total evaluated) autoantibodies in zymosan-injected female and orchiectomized male mice compared to intact male control mice (q < 5.2%).

DISCUSSION

Rheumatoid arthritis is a progressive systemic autoimmune disease that affects approximately 1% of the population with a gender bias that is at least 3:1 female to male. Herein, we have shown that SKG mice represent an authentic, sexually dimorphic mouse model of human rheumatoid arthritis. Similar to human RA, arthritis is more prevalent and severe in female SKG mice compared to male mice and can be associated with progressive interstitial lung disease. Further, we have shown that testosterone protects against the development of joint and lung disease in male SKG mice and is associated with alterations in the production of antibodies to citrullinated protein antigens.

One of the primary goals of this study was to investigate the role of testosterone in an autoimmune mouse model of RA. Low levels of testosterone have been linked to disease severity in men with RA (5) and supplemental testosterone has been shown to reduce disease severity in both postmenopausal women and men with low testosterone (11, 12). It remains unclear if low testosterone reflects a primary risk factor for the development of RA or represents an effect of chronic inflammation. This was demonstrated by the universally low testosterone levels seen in the mice that received surgical sham procedures. It is important not to underestimate the impact of stress-induced changes in the HPA axis on hormone production as it represents a confounder in any surgical procedure to induce low testosterone. Interestingly, human clinical studies have also shown decreased testosterone levels related to general anesthesia, surgical stress, and other forms of inflammation including sepsis and end-stage renal disease (13–15).

Sex steroids likely play an important role in the gender differences seen in sexually dimorphic diseases such as RA. However, the mechanisms by which sex and sex steroids affect the immune system and autoimmunity remain poorly understood. Estrogen receptors are expressed in many cells of the immune system including lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, NK cells, and dendritic cells (2). Estrogen has been shown to have multiple effects on the immune system including promotion of Th2 T-cell skewing, increasing numbers of T regulatory CD4+ T-cells, B-cells, and immunoglobulin production (2). Androgen receptors are also found in lymphocytes and testosterone itself has been associated with Th1 T-cell skewing and B-cell tolerance (2). Additionally, androgen receptor knock-out mice have increased numbers of B-cells and are more susceptible to collagen induced arthritis (16). Taken together, these findings suggest that sex hormones play a significant role in fine-tuning the immune system and impact the development of autoimmunity in part by altering B-cell biology, T-cell skewing, and immunoglobulin production.

Accumulation of citrullinated proteins occurs in the context of many inflammatory conditions. However, it is the presence of a specific antibody response to citrullinated proteins that is characteristic of RA (17). Proteins become citrullinated when there is a post-translational modification of the positively charged amino acid arginine to the neutral amino acid citrulline. This can lead to changes in protein structure and the creation of neo-epitopes presenting altered self-antigens, which can lead to breaches in immunologic tolerance. Citrullinated fibrinogen/fibrin, vimentin, collagen type II, filaggrin, and α-enolase have been identified as specific auto-antigens in human RA (17, 18). In mice with low-grade collagen-antibody induced arthritis, infusion of antibodies to citrullinated fibrinogen has been shown to increase arthritis severity suggesting a direct pathogenic role for these antibodies (18). In this study we have demonstrated that zymosan-injected arthritic SKG mice produce clinically relevant antibodies to citrullinated proteins including fibrinogen, vimentin, filaggrin and enolase. In addition, we have shown that the presence or absence of these hormones is a modifying factor in the production of ACPA in SKG mice.

In summary, testosterone protects against the development of autoimmune arthritis and lung disease in male SKG mice. The removal of testosterone increases both lung and joint disease in male mice creating a phenotype that is intermediate between that of intact males and females. We speculate that this is in part due to the ability of testosterone to modulate the development of antibodies against citrullinated proteins. Thus, we conclude that SKG mice represent a useful model that will allow future investigation of sex differences contributing to the development of both inflammatory arthritis and associated interstitial pneumonia. This model may additionally provide a unique opportunity to investigate the role of ACPA in both the preclinical phase of disease and in the progression of joint and lung disease.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Funding for this research was made possible in part by a grant from the ACR Research and Education Foundation Within Our Reach: Finding a Cure for Rheumatoid Arthritis campaign, Public Health Service grants HL68628 (DWHR), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 1F32HL095274 (EFR).Grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Sports, and Culture of Japan (SS), and Institutional T-32 HL00048 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (RCK).

The authors wish to acknowledge outstanding technical assistance provided by Dawn Bohrer-Kunter, Linda Remigio, and the National Jewish Health Biological Resource Center. The authors also acknowledge Steve Binder and Michelle Delanoy of Bio-Rad Laboratories for their provision of ACPA bead-arrays.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NM. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84(3):223–43. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennell LM, Galligan CL, Fish EN. Sex affects immunity. J Autoimmun. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janele D, Lang T, Capellino S, Cutolo M, Da Silva JA, Straub RH. Effects of testosterone, 17beta-estradiol, and downstream estrogens on cytokine secretion from human leukocytes in the presence and absence of cortisol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1069:168–82. doi: 10.1196/annals.1351.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rettew JA, Huet-Hudson YM, Marriott I. Testosterone reduces macrophage expression in the mouse of toll-like receptor 4, a trigger for inflammation and innate immunity. Biol Reprod. 2008;78(3):432–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.063545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tengstrand B, Carlstrom K, Hafstrom I. Gonadal hormones in men with rheumatoid arthritis--from onset through 2 years. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(5):887–92. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Sprunger DB, Fischer A, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease-associated mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):372–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0622OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keith RC, Powers JL, Redente EF, Sergew A, Martin RJ, Gizinski A, et al. A novel model of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease in SKG mice. Exp Lung Res. 2012;38(2):55–66. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2011.636139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sokolove J, Lindstrom TM, Robinson WH. Development and deployment of antigen arrays for investigation of B-cell fine specificity in autoimmune disease. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:320–30. doi: 10.2741/379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, et al. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118(7):1952–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokolove J, Zhao X, Chandra PE, Robinson WH. Immune complexes containing citrullinated fibrinogen costimulate macrophages via Toll-like receptor 4 and Fcgamma receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):53–62. doi: 10.1002/art.30081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booji A, Biewenga-Booji CM, Huber-Bruning O, Cornelis C, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. Androgens as adjuvant treatment in postmenopausal female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(11):811–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.11.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutolo M, Balleari E, Giusti M, Intra E, Accardo S. Androgen replacement therapy in male patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(1):1–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakashima A, Koshiyama K, Uozumi T, Monden Y, Hamanaka Y. Effects of general anaesthesia and severity of surgical stress on serum LH and testosterone in males. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1975;78(2):258–69. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0780258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christeff N, Benassayag C, Carli-Vielle C, Carli A, Nunez EA. Elevated oestrogen and reduced testosterone levels in the serum of male septic shock patients. J Steroid Biochem. 1988;29(4):435–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(88)90254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrero JJ, Qureshi AR, Nakashima A, Arver S, Parini P, Lindholm B, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of testosterone deficiency in men with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(1):184–90. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altuwaijri S, Chuang KH, Lai KP, Lai JJ, Lin HY, Young FM, et al. Susceptibility to autoimmunity and B cell resistance to apoptosis in mice lacking androgen receptor in B cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(4):444–53. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wegner N, Lundberg K, Kinloch A, Fisher B, Malmstrom V, Feldmann M, et al. Autoimmunity to specific citrullinated proteins gives the first clues to the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233(1):34–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn KA, Kulik L, Tomooka B, Braschler KJ, Arend WP, Robinson WH, et al. Antibodies against citrullinated proteins enhance tissue injury in experimental autoimmune arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(4):961–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI25422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]