Abstract

Previously we developed an estrogen receptor β-selective phytoestrogenic (phytoSERM) combination, which contains a mixture of genistein, daidzein, and racemic R/S-equol. The phytoSERM combination was found neuroprotective and non-feminizing both in vitro and in vivo. Further, it prevented or alleviated physical and neurological changes associated with human menopause and Alzheimer’s disease. In the current study, we conducted translational analyses to compare the effects of racemic R/S-equol-containing with S-equol-containing phytoSERM therapeutic combinations on mitochondrial markers in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures and in a female mouse ovariectomy (OVX) model. Data revealed that both the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments regulated mitochondrial function, with S-equol phytoSERM combination eliciting greater response in mitochondrial potentiation. Both phytoSERM combination treatments increased expression of key proteins and enzymes involved in energy production, restored the OVX-induced decrease in activity of key bioenergetic enzymes, and reduced OVX-induced increase in lipid peroxidation. Comparative analyses on gene expression profile revealed similar regulation between S-equol phytoSERM and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments with minimal differences. Both combinations regulated genes involved in essential bioenergetic pathways, including glucose metabolism and energy sensing, lipid metabolism, cholesterol trafficking, redox homeostasis and β-amyloid production and clearance. Further, no uterotrophic response was induced by either of the phytoSERM combinations. These findings indicate translational validity for development of an ER β selective S-equol phytoSERM combination as a nutraceutical to prevent menopause-associated symptoms and to promote brain metabolic activity.

Keywords: equol, phytoSERM, mitochondria, oxidative stress, bioenergetics

1. Introduction

In addition to the well-established application for alleviation of menopausal symptoms, estrogen-containing hormone therapy (ET) has been widely indicated for its positive roles in maintaining neurological health in postmenopausal women (Brinton, 2008; Brinton, 2009). Ovarian hormone loss in menopause has been associated with an increased risk for cognitive decline and development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Brinton, 2008; Brinton, 2009). Despite the health benefits, the use of ET has been rather controversial. Earlier studies suggested increased risk for breast cancer and blood clots associated with hormone therapy (Hammond, 1994; Ravdin et al., 2007), however recent preclinical and clinical investigations indicated that the increased risk of breast cancer was in fact associated with a specific hormone therapy regimen with the usage of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) and a specific progestin, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, otherwise known as Provera)(Stanczyk et al., 2012).

Investigations to identify effective and safe alternatives to ET have focused on plant-derived estrogenic compounds, known as phytoestrogens. These compounds bind at weak to moderate affinities to estrogen receptors (ERs) and exert estrogenic or anti-estrogenic activities (Dixon, 2004; Setchell, 1998). A great number of both basic science research and clinical observations have suggested that phytoestrogens could be beneficial in prevention and treatment of multiple sex hormones-related disorders including menopausal hot flashes, breast cancer (Ziegler, 2004), prostate cancer (Goetzl et al., 2007), and AD (Zhao and Brinton, 2007).

Soy-derived isoflavones, genistein and daidzein, have been the two most studied phytoestrogens. The third compound, equol, as a unique daizein metabolite, has attracted increasing interest due to its high potency to induce estrogenic responses of clinical relevance (Setchell and Clerici, 2010a; Setchell and Clerici, 2010b). Unlike genistein and daidzein, equol is not a direct plant origin, but is can be exclusively produced through the metabolism of daidzein catalyzed by intestinal microbial flora following the intake of soy products (Setchell et al., 1984). Equol is a chiral compound and can exist in three forms, racemic (±)equol (R/S-equol), R-equol and S-equol. S-equol is found to be the exclusive enantiomer present in the urine of about 20-30% of Western adults after consuming soy products, and this sub-population are defined as “equol-producers” (Setchell et al., 2005; Setchell and Cole, 2006).

Most of the published studies on equol have been based on the racemic form, (±) equol, including our previous studies on phytoSERM therapeutic combinations (Zhao et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2011). Until recently, a few reports comparatively analyzed equol isomers and results indicate that these isomers share both similarities and differences in biological properties. An earlier in vitro study done by Magee et al found that racemic R/S-equol and S-equol induced equipotent inhibition of the growth and invasion of breast and prostate cancer cells, while only racemic R/S-equol prevented DNA damage against a genotoxic insult (Magee et al., 2006). Another in vitro study reported by Shinkaruk et al confirmed that both R-equol and S-equol exert transcriptional activities despite differences with respect to the involvement of ER subtype and transactivation functions (Shinkaruk et al., 2010). In a chemically induced rat model of breast cancer, it was observed that S-equol had no chemopreventive action, nor was it stimulatory, while R-equol was found potently chemopreventive, with an impressive 43% tumor reduction (Brown et al., 2010). Together, these studies underlie the importance of further investigations to elucidate potential impact of different equol forms on human health and disease.

In the present study, we compared the effects of racemic R/S-equol-based with S-equol-based phytoSERM combinations on mitochondrial markers in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures and mouse whole brain. Results from our analyses indicate that both combinations similarly potentiate mitochondrial function in female brain.

2. Results

2.1 Both S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations promote neuronal mitochondrial bioenergetics in vitro

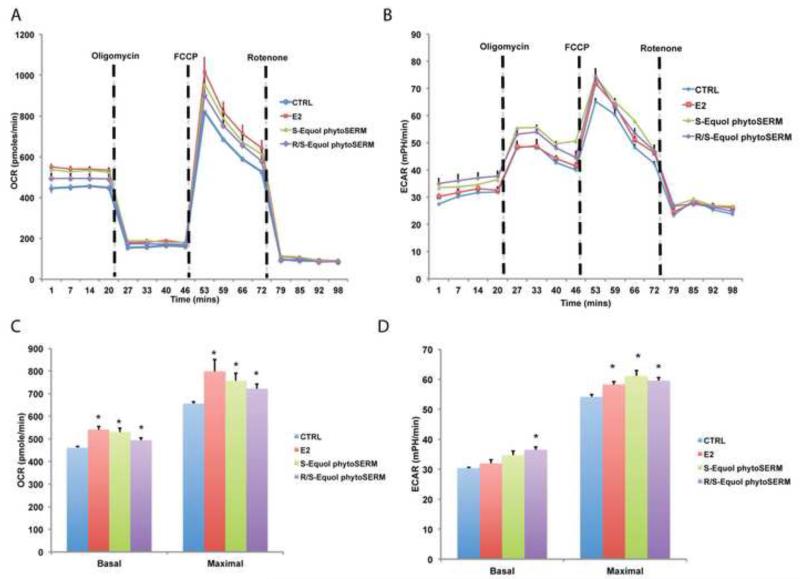

To determine the metabolic efficacy of S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations in vitro, we measured their regulation of mitochondrial respiration (indicated by OCR) as well as aerobic glycolysis (indicated by ECAR) in primary neuronal cultures. E2 was included as a positive control as we previously demonstrated that E2 up-regulated mitochondrial respiration both in vitro and in vivo (Yao et al., 2011; Yao et al., 2012). In primary neurons over 80% of OCR measured was due to oxidative phosphorylation as indicated by the decrease (>80% decrease relative to basal level) in OCR with the addition of the Complex I inhibitor rotenone. The addition of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (1 μM) resulted in about 70% decrease in OCR in neurons (Fig. 1A), indicating that oxygen consumption was largely driven by oxidative phosphorylation-coupled ATP generation. Compared to the vehicle group, all three treatment groups significantly increased both the basal mitochondrial respiration and the maximal respiratory capacity with E2 demonstrating the greatest potency followed by S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations respectively (Fig. 1A and 1C). In contrast, only the R/S-equol phytoSERM combination induced a moderate increase in basal aerobic glycolysis level while all three treatments increased the maximal aerobic glycolysis rate (Fig. 1B and 1D).

Figure 1. Both S-equol phytoSERM and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments promotes mitochondrial bioenergetics in vitro.

Primary hippocampal neurons were treated with S-equol phytoSERM combination (100 nM), R/S-equol phytoSERM combination (100 nM), E2 (10 nM), or vehicle for 24 hours. Cellular metabolic flux activity was measured using the Seahorse metabolic analyzer. A&C, Both E2 (Red), S-equol phytoSERM (green), and R/S-equol phytoSERM (purple), increased the basal respiration and maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity (indicated by OCR, Oxygen consumption Rate) relative to vehicle control (blue). A, representative OCR VS Time curve; C, bar graphs of basal and maximal mitochondrial respiration (*, p<0.05 compared to vehicle group, n=5 per group). B&D, R/S-equol phytoSERM (purple) combination increased the basal aerobic glycolysis (indicated by ECAR, Extracellular Acidification Rate), while E2 (Red), S-equol phytoSERM (green), and R/S-equol phytoSERM (purple), increased the maximal aerobic glycolysis rate. B, representative ECAR VS Time curve; D, bar graphs of basal and maximal aerobic glycolysis (*, p<0.05 compared to vehicle group, n=5 per group).

2.2 No peripheral uterotrophic effects of S-equol or R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations

In the current study, uterine weight was used as a bioassay to confirm depletion of ovarian hormones and to investigate the potential proliferative side-effect of phytoSERM treatments. OVX-induced hormone depletion resulted in a significant decrease in uterine weight relative to the Sham-OVX group (Fig. 2, p<0.05). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in uterine weight between the OVX group and the phytoSERM treatment groups, indicating that neither the S-equol nor the R/S-equol phytoSERM combination induced uterine proliferation.

Figure 2. No peripheral uterotrophic effects of S-equol or R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments.

Uteri were collected at sacrifice from Sham OVX, OVX, OVX+S-equol phytoSERM, and OVX+R/S-equol phytoSERM mouse groups and weighed respectively. Values represent mean uterine weight ± SEM (*, p<0.05 compared to OVX group, n=8 per group).

2.3 S-equol and R/S –Equol phytoSERM combinations regulated key metabolic enzyme activity

To investigate the regulation of S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations on brain metabolic activity in vivo, we measured activities of four key enzymes involved in mitochondrial bioenergetics: PDH (pyruvate dehydrogenase), αKGDH (α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase), complex I (NADH dehydrogenase), and complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase). PDH is the key enzyme linking glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS); αKGDH is the rate-limiting enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle; Complex I controls the entry of electron flow to the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mETC), hence controlling the entry point of OXPHOS in brain; Complex IV is the terminal enzyme of electron flow and reduces O2 to H2O. Complex I activity was not changed by either OVX or the phytoSERM treatments. In contrast, OVX induced a significant decrease in PDH activity (Fig. 3A, p<0.05), a moderate but not significant decrease in αKGDH activity (Fig. 3B) and had no impact on Complex I and Complex IV activity (Fig. 3C and 3D). Compared to the OVX group, the S-equol phytoSERM combination induced significant increase in PDH activity (Fig. 3A, p<0.05) whereas R/S-equol phytoSERM combination induced a moderate but not significant increase in PDH activity (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the S-equol phytoSERM combination induced significant increase in αKGDH activity and complex IV activity (Fig. 3B and 3D, p<0.05) whereas R/S-equol phytoSERM combination induced a moderate but not significant increase (Fig. 3B and 3D, p<0.05).

Figure 3. S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations regulated mitochondrial bioenergetic enzyme activity.

Crude cortical mitochondria isolated from Sham OVX, OVX, OVX + S-equol phytoSERM combination, and OVX + R/S-equol phytoSERM combination groups were assessed for PDH, αKGDH, Complex I and Complex IV (COX) activities respectively. A, S-equol reversed the OVX-induced decrease in PDH activity, relative PDH activity was presented as the relative value normalized to that of OVX group; B, S-equol reversed the OVX-induced decrease in KGDH activity, relative KGDH activity was presented as the relative value normalized to that of OVX group; C, no significant change in complex I activity with OVX, S-equol phytoSERM, or R/S-equol phytoSERM treatment, relative Complex I activity was presented as the relative value normalized to that of OVX group; D, S-equol reversed the OVX-induced decrease in COX activity, relative COX activity was presented as the relative value normalized to that of OVX group; Bars represent mean enzyme activity value ± SEM (*, p<0.05 compared to OVX group, n=8 per group).

2.4 S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations regulated expression and post-translational modification of bioenergetics enzymes

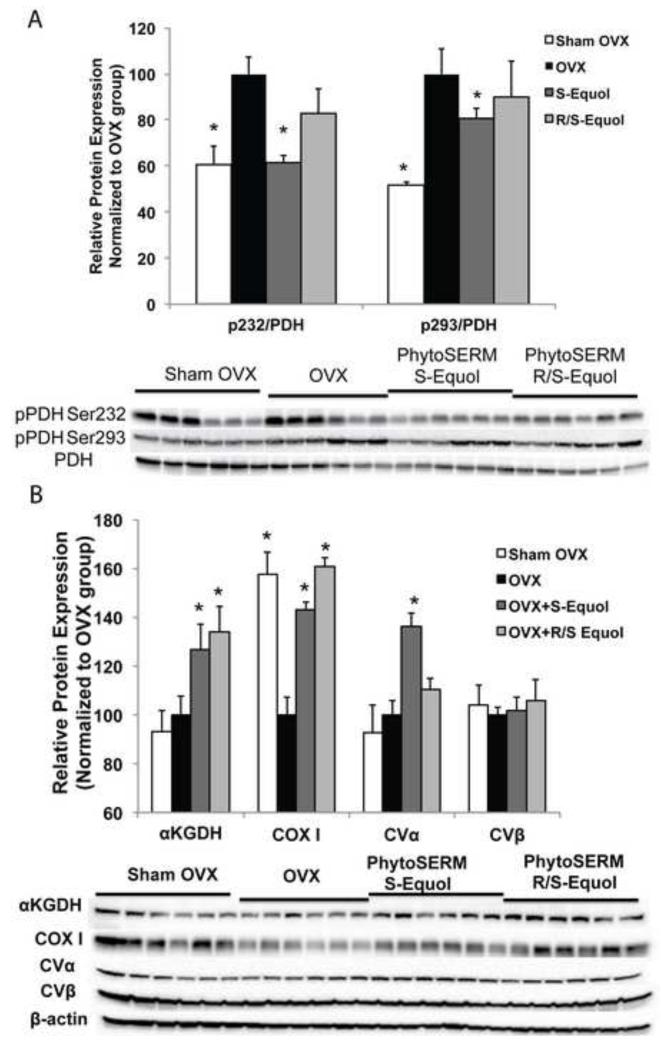

Changes in enzyme activities can be attributed to changes in protein expression or post-translational modification, such as phosphorylation. PDH as the control point between aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial OXPHOS can be phosphorylated as a regulatory mechanism of its activity. To investigate the impact of OVX and the phytoSERM treatments on PDH phosphorylation, we conducted western blot analyses on two of the phosphorylation sites of PDH, phosphoSer232 (pSer232) and phosphoSer293 (pSer293). Compared to the Sham group, OVX induced a significant increase in phosphorylation at Ser232 and Ser293 site (Fig, 4A, p<0.05). S-equol phytoSERM combination significantly reduced the OVX-induced increase in both pSer293 and pSER232 (Fig. 4A, p<0.05) whereas R/S-equol phytoSERM combination only significantly reduced phosphorylation of PDH at the Ser232 site (Fig. 4A, p<0.05). In addition to PDH phosphorylation, we investigated impact of OVX and phytoSERM treatments on protein expression of KGDH, COX I (cytochrome c oxidase, subunit I), CVα (ATP synthase, subunit α) and CVβ (ATP synthase, subunit β). OVX induced a significant decrease in COXI protein expression, while both S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments induced significant increase in COXI expression (Fig. 4B, p<0.05). Both the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination significantly increased expression of αKGDH (Fig. 4B, p<0.05) while OVX had minimal impact on KGDH protein expression (Fig. 4B, p<0.05). Only the S-equol phytoSERM combination induced significant increase in CVα compared to the OVX group whereas the R/S-equol combination induced a moderate but not significant increase. For CVβ, there was no change with OVX or either phytoSERM treatments.

Figure. 4. S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments regulated expression and post-translational modification of bioenergetics enzymes.

Crude cortical mitochondrial samples of Sham OVX, OVXOVX + S-equol phytoSERM, and OVX + R/S-equol phytoSERM treatment groups were analyzed for protein levels of pSer232-PDH, pSer293-PDH, and total PDHE1α levels; Hippocampal homogenates samples of Sham OVX, OVXOVX + S-equol phytoSERM, and OVX + R/S-equol phytoSERM treatment groups were analyzed for protein levels of bioenergetic enzymes, including αKGDH, COXI, CVα and CVβ. A, OVX induced significantly increase in pPDH levels, which was reversed by S and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments (*, p<0.05 compared to OVX, bars represent mean value ± SEM, n=6 per group); B, S-equol and R/S-equol regulated expression of αKGDH, COXI, CVα but not CVβ (*, p<0.05 compared to OVX, bars represent mean value ± SEM, n=6 per group).

2.5 S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations reduced OVX-induced increase in lipid peroxidation

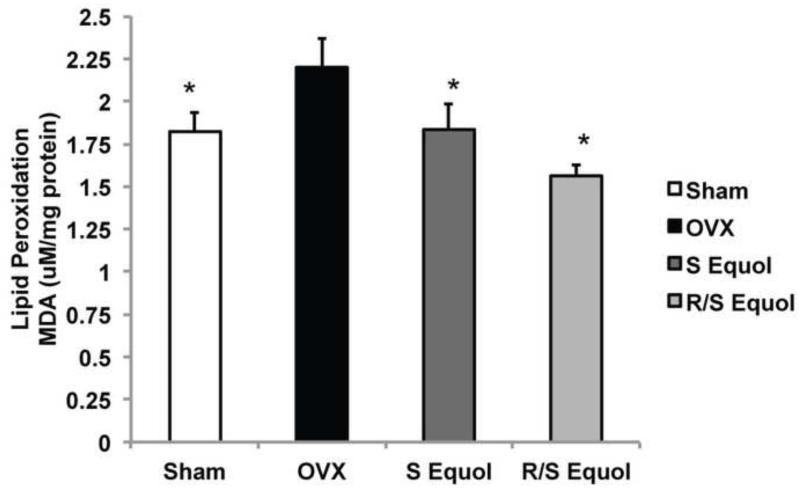

Oxidative stress is involved in the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases. To investigate the efficacy of S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations to reduce oxidative damage, we conducted the T-BARS assays as a functional readout of lipid peroxidation status. Compared to the Sham group, OVX induced a significant increase in lipid peroxidation (Fig. 5, p<0.05). Moreover, both the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments significantly reduced lipid peroxidation to a level comparable to (S-equol phytoSERM) or lower than (R/S-equol phytoSERM) the Sham group (Fig. 5, p<0.05).

Figure. 5. S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments reduced OVX-induced increase in lipid peroxidation.

Hippocampal tissue homogenates from the Sham OVX, OVX, OVX + S-equol phytoSERM, and OVX + R/S-equol phytoSERM groups were analyzed lipid peroxidation by T-BARS assay. OVX induced a significant increase in lipid peroxidation, which was reversed by both S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments (*, p<0.05 compared to OVX, bars represent mean value ± SEM, n=8 per group).

2.6 S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combinations induced a similar response in expression of mitochondrial and bioenergetics genes

To investigate the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination regulation of brain bioenergetics on a systems-level, we conducted target driven Low Density gene Arrays (LDA), which contains a total of 197 genes involved in essential pathways of brain metabolism and mitochondrial function. Compared to the OVX group, the S-equol phytoSERM combination induced significant increase in 14 genes, including Aacs, Acaa2, Glrx, Ldhb, Prkaa1, Star, Adam17, Opa1, Prep, Timm22, Cyp46a1, Ogdh, Txn2, Psen2, and a significant decrease in 1 gene, Gsr. The R/S-equol phytoSERM combination induced significant increase in 8 genes, including Cyp46a1, Ogdh, Txn2, Psen2, Abca1, Pdha1, Pdhb, Apba3, and significant decrease in 1gene, Gpx3 (Fig. 6A, p<0.05, Table 1). Comparison between the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination groups revealed similar bioenergetics profiles of these two treatment groups with only 8 genes significantly changed, including Lcat, Apba1, Ece2, Echs1, Gsr, Timp2, Adam17, and Opa1 (Fig. 6B, p <0.05, Table 1).

Figure 6. S-equol and R/S-equol regulated bioenergetic gene expression profile.

RNA samples isolated from hippocampal tissues of all groups were analyzed for gene expression with custom LDA mouse mitochondrial array. A, Genes that were significantly regulated by S-equol phytoSERM and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments (red and green, significantly increased or decreased compared to OVX, respectively); B, genes significantly changed in the S-equol phytoSERM treatment group relative to the R/S-equol phytoSERM group (red and green, significantly increased or decreased compared to R/S-equol phytoSERM treatment group, respectively).

Table. 1. Comparative analyses of gene expression regulation by S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments.

RNA samples isolated from hippocampal tissues of all groups were analyzed for gene expression with custom LDA mouse mitochondrial array. Significantly changed genes were categorized into 5 different functional groups: lipid metabolism; glucose metabolism and energy sensing; cholesterol trafficking; redox homeostasis; and Aβ production and clearance. Data is presented as relative fold change with the corresponding p value listed for each individual gene.

| Functional Group |

Gene Symbol |

Gene Expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-equol phytoSERM vs OVX |

R,S-equol phytoSERM vs OVX |

S-equol phytoSERM vs R/S-equol phytoSERM |

|||||

| Fold Change |

P- Value |

Fold Change |

P- Value |

Fold Change |

P- Value |

||

|

Lipid Metabolism |

Aacs | 2.57 | 0.038* | ||||

| Acaa2 | 1.23 | 0.038* | |||||

| Echs1 | 0.77 | 0.049* | |||||

|

Glucose Metabolism/ Energy Sensing |

Ldhb | 1.27 | 0.041* | ||||

| Ogdh | 1.26 | 0.024* | 1.27 | 0.003 | |||

| Pdha1 | 1.31 | 0.027 | |||||

| Pdhb | 1.26 | 0.032 | |||||

| Prkaa2 | 1.38 | 0.017* | |||||

| Opa1 | 1.16 | 0.003* | 1.07 | 0.012 | |||

|

Cholesterol Trafficking and Metabolism |

Cyp46a1 | 1.53 | 0.020* | 2.06 | 0.040* | ||

| Star | 1.94 | 0.033* | |||||

| Acba1 | 1.17 | 0.008** | |||||

| Lact | 0.71 | 0.034* | |||||

|

Redox Homeostasis |

Glrx | 1.19 | 0.047* | ||||

| Gpx3 | 0.39 | 0.027* | |||||

| Txn2 | 1.23 | 0.022* | 1.18 | 0.047* | |||

| Gsr | 0.59 | 0.049* | 0.61 | 0.034* | |||

|

Aβ Production and Clearance |

Adam17 | 1.46 | 0.030* | 1.41 | 0.044* | ||

| Apba1 | 0.70 | 0.049* | |||||

| Apba3 | 1.51 | 0.022* | |||||

| Psen2 | 1.63 | 0.040* | 1.41 | 0.012* | |||

| Ece2 | 0.80 | 0.024* | |||||

3. Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that both S-equol phytoSERM and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments potentiated mitochondrial bioenergetics in vitro and in vivo, albeit fine differences in efficacy of anti-oxidant and gene expression profile. From a mechanistic perspective, the current study provided direct comparison between impact of S-equol and R/S-equol based phytoSERM combination treatments on brain mitochondrial function. From a translational and regulatory science perspective, findings that S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments share largely the same efficacy profile enables development of S-equol phytoSERM combination as a dietary nutraceutical for relieving hot flash symptoms and promoting general brain health in post-menopausal women.

3.1 Efficacy of S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments to potentiate mitochondrial function

Mitochondrial function is a key regulator of aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (Beal, 2005; Lin and Beal, 2006). We previously demonstrated that in a rat ovariectomy model, the same R/S-equol phytoSERM combination promoted brain mitochondrial function, increased COX activity and increased expression of anti-apoptotic protein bcl-2 and bcl-xl (Zhao et al., 2009). Data from the current study are consistent with our previous findings. In the current study, we further demonstrated that the S-equol phytoSERM combination treatment, to a greater extent than the R/S-equol phytoSERM treatment, increased mitochondrial respiration in cultured primary neurons and potentiated whole brain mitochondrial function in a mouse model of ovariectomy. While both phytoSERM treatments generally enhanced mitochondrial respiration in vitro, the S-equol phytoSERM treatment, in particular, induced greater increase in the activity of key bioenergetics enzymes, including the PDH, αKGDH and COX activity, suggesting that the S-equol phytoSERM treatment induced a tightly-coordinated potentiation of the mitochondrial bioenergetics system, spanning from the link between aerobic glycolysis (PDH), to the TCA Cycle (αKGDH) and to the electron transport chain (COX). The difference between the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM could be caused by the difference in the dosage of S-equol in the two treatments (only half S-equol in the R/S-equol combination) or a potential antagonistic interaction between R-Equol and S-equol. To address these possibilities, further studies are currently under way.

3.2 Transcriptional/translational regulation and post-translational modifications of bioenregetic enzymes by phytoSERM treatments

In the current study, we demonstrated that multi-factorial bioenergetic regulation by both phytoSERM treatments. Both phytoSERM treatments induced an increase in expression of key bioenergetic enzymes, including KGDH, cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, ATP synthase subunit, suggesting a coordinated enhancement of the brain bioenergetic system. Aside from the transcriptional and translational regulation that alters the expression level of bioenergetics enzymes and proteins, we demonstrated that phytoSERM treaments modified post-translational status of the proteins and enyzmes. PDH can be phosphorylated at different serine residues, which leads to inactivation of the PDH enzyme complex (Yin et al., 2012). In the current study, consistent with the decrease in PDH activity, we demonstrated that OVX induced significant increase in PDH phosphorylation at two serine sites, Ser293 and Ser232. S-equol phytoSERM combination reduced the phosphorylation at PDH Ser293 and Ser232, to a level comparable to the Sham group, whereas R/S-equol combination only induced moderate but not significant reduction of PDH phosphorylation. Difference in magnitude of PDH phosphorylation status may account for the difference in PDH activity between the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatment groups. In the current study we also observed that OVX induced a decrease in αKGDH activity with minimal impact on the protein expression of αKGDH, suggesting a potential post-translational regulatory mechanism of αKGDH enzyme complexes. Previous studies demonstrated that KGDH could be de-activated by oxidative insults, particularly nitrosative stress (Gibson et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2011). Therefore, it is possible that the increase in oxidative stress induced by OVX contributed to the decrease in αKGDH and/or complex V activity without directly altering their protein expression level, whereas phytoSERM treatments enhanced the enzyme complexes through simultaneous up-regulation of protein expression and suppression of oxidative-stress associated deactivation of the enzyme systems.

3.3 Reduction of oxidative damage by phytoSERM combinations

Oxidative stress closely parallels deficits in mitochondrial bioenergetics and development of AD neuropathology. Increased oxidative modification of key metabolic enzymes will lead to compromised enzyme activity, decreased energy production (Packer and Cadenas, 2007) and activation of pathogenic pathways of many age-related neurodegenerative diseases (Moreira et al., 2007; Nunomura et al., 2001). Estrogenic pathways have been demonstrated to regulate key components in the anti-oxidative defense system, through genomic and non-genomic estrogen signaling pathways (Asthana et al., 2009; Irwin et al., 2008; Nilsen et al., 2007; Vina et al., 2005). In addition, soy-based isoflavones, such as daizein, genistein, and equol have long been documented to provide anti-oxidant benefits in multiple studies (Gilbert and Liu, 2012; Gopaul et al., 2012; Hagen et al., 2012; Lateef et al., 2012). Consistent with previous findings, we demonstrated that both the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments significantly reduced the OVX-induced increase in lipid peroxidation. Moreover, the R/S-equol phytoSERM combination induced greater reduction in lipid peroxidation, suggesting a potential additive and/or synergistic benefits of R-Equol in the combination.

3.4 Similarity and difference in gene expression profile between S-equol phytoSERM and R/S-equol phytoSERM combination treatments

Equol has been well documented to be protective against multiple oncogenic and neurodegenerative insults (Ma et al., 2010; Schreihofer and Redmond, 2009; Setchell and Clerici, 2010b; Zhao et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2011). Despite the structural similarity, S-equol and R-Equol exhibit different binding and biochemical activity through estrogen receptors. While S-equol exhibited higher binding affinity, preferential for ERβ, R-Equol binds more weakly and with a preference for ERα (Muthyala et al., 2004). In addition, S-equol and R-Equol exhibited different pharmacokinetic and bioavailability profiles (Setchell et al., 2009). Moreover, the biological and clinical benefit difference between the S-equol and R-Equol has not been fully elucidated. A recent study demonstrated that R- and S-equol have equivalent cytoprotective effects in Friedreich’s Ataxia (Richardson and Simpkins, 2012). Similarly, it was demonstrated that both S-equol and R-Equol inhibited motility and invasion in PC3 and Du145 cells, with R-Equol exhibiting greater effect (2011). In contrast, Brown and colleagues reported that in a chemically induced animal model of breast cancer, S-equol exhibited no chemopreventive action, nor was it stimulatory whereas R-Equol was potently chemopreventive (Brown et al., 2010). In the current study, we conducted comparative gene expression profile analyses from a mitochondrial bioenergetic perspective between S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments. Data from these analyses revealed similar gene expression profile with fine difference. Compared to the OVX group, phytoSERM treatments regulated expression of genes involved the following functional domains: glucose metabolism and energy sensing pathways, redox homeostasis, Aβ production and clearance, and lipid and cholesterol homeostasis (Fig. 6A, Table 1). A direct comparison of gene expression profiles between these two phytoSERM treatments revealed fine differences in 8 genes out of 196 genes examined. While the S-equol phytoSERM combination induced greater changes in α-secretase (ADAM 17) and mitochondrial fusion protein (Opa1) gene expression, the R/S-equol phytoSERM combination activated greater gene expression involved in lipid metabolism and Aβ clearance (Fig. 6B, Table 1). Together with the biochemical analyses, the S-equol phytoSERM combination and the R/S-equol phytoSERM combination largely induced similar cellular responses to potentiate mitochondrial function in vitro and in vivo. The minimal differences between the S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM observed in the current study could be attributed to the difference in the dosage of S-equol in the two treatments (only half S-equol in the R/S-equol combination) or a potential interaction between R-Equol and S-equol. To address these possibilities, further studies are currently under way.

3.5 Translational implications

Increasing evidence supports the translational potential of targeting ER β as a safe alternative to ET (Table 2) (Akaza et al., 2004; Atkinson et al., 2005; Ishiwata et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2010; Jou et al., 2008; Muthyala et al., 2004; Romagnolo and Selmin, 2012; Setchell et al., 2002; Setchell et al., 2005; Setchell et al., 2009; 2011; Uchiyama et al., 2007; Vatanparast and Chilibeck, 2007; Vitale et al., 2012; Yee et al., 2008; Zhao and Brinton, 2007). In the current study, we demonstrated that both ER β-selective S-equol and R/S-equol phytoSERM treatments induced similar changes in gene expression profile, restored the OVX-induced deficits in brain mitochondrial function and suppressed the OVX-induced increase in oxidative damage without an uterotrophic adverse-effect that is associated with estrogen treatment. Considering the critical role of mitochondrial bioenergetics and function in brain metabolism, findings from the current study indicate great potential to develop the S-equol phytoSERM ER β selective formulations as a nutraceutical strategy to prevent the menopause-associated decline in brain metabolism and therefore prevent against age-associated neurodegenerative diseases.

Table. 2. Summary of pre-clinical and clinical studies on efficacy and safety of ER β selective S-equol phytoSERM treatments against menopause-associated symptoms.

| Article | Reference | Purpose | Test Subject |

Route | Dose | Results | Safety of S- equol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute and subchronic toxicity and genotoxicty of SE5- OH, an equol-rich product produced by Lactococcus garvieae |

(Yee, Burdock et al. 2008) | To investigate SE5-OH as an equol introduction strategy for those who can not convert daidzein to equol |

Rat | oral gavage |

2 doses of 2000mg/kg SE5-OH separated by 4 hours |

SE5-OH is neither toxic nor genotoxic. |

One control female animal found to have a small spleen and “a yellow- brown mesenteric nodule”, although categorized as “unrelated to treatment” |

| Equol, a natural estrogenic metabolite from soy isoflavones: convenient preparation and resolution of R- and S-equols and their differing binding and biological activity through estrogen receptors alpha and beta |

(Muthyala, Ju et al. 2004) | To prepare racemic and pure enantiomers of equol from isoflavoid precursers, optimization of separation of enantiomers by HPLC, and to study equol enantiomer activities on ERα and ERβ |

Human endometrial carcinoma (HEC-1) cells |

n/a | assay | S-equol has higher binding affinity to ERβ, and R- equol has higher binding affinity to ERα. Both equol enantiomers have much higher binding affinity to ER than their precursors. |

No adverse effects reported |

| Comparisons of Percent Equol Producers between Prostate Cancer Patients and Controls: Casecontrolled Studies of Isoflavones in Japanese, Korean and American Residents |

(Akaza, Miyanaga et al. 2004) | To study the percent of equol producers in Japanese, Korean, and American Residents |

Human | n/a | n/a | Percent of equol producers is lower for the group with prostate cancer. The American group serum isoflavones levels were lower than the Japanese and Korean groups. |

No adverse effects reported |

| S-Equol, a potent ligand for estrogen receptor β, is the exclusive enantiomeric form of the soy isoflavone metabolite produced by human intestinal bacterial flora |

(Setchell, Clerici et al. 2005) | To characterize the exact structure of equol, to examine whether the S- and R- equol enantiomers are bio- available, and to ascertain whether the differences in their conformational structure translate to significant differences in affinity for estrogen receptors |

Human | oral | soy food from diet |

S-equol is synthesized by intestinal bacteria and has high affinity for Erβ. |

No adverse effects reported |

| The cross-sectional study of the relationship between soy isoflavones, equol and the menopausal symptoms in Japanese women |

(Uchiyama, Ueno et al. 2007) | To investigate the relationship between urinary excretion of isoflavones and menopausal symptoms of Japanese women in peri- and postmenopausal periods |

Human Female |

n/a | This study compared menopausal symptom intensity to urinary excretion of isoflavones from their natural diets. |

Equol producers reported milder menopausal symptoms, and “urinary equol excretion of at least 5μmol/24hr is required to reduce everyday menopausal symptoms”. |

No adverse effects reported |

| Effect of intestinal production of equol on menopausal symptoms in women treated with soy isoflavones |

(Jou, Wu et al. 2008) | To evaluate the effect of soy isoflavones on menopausal symptoms in women who do and who do not produce equol, a daidzein metabolite. |

Human | oral | 135mg isoflavones daily for one week |

Compared to placebo, equol producers experienced a reduction of menopausal symptoms. |

No adverse effects reported |

| New equol supplement for relieving menopausal symptoms:Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Japanese women |

(Ishiwata, Melby et al. 2009) | To examined the effect of a new S-equol supplement on menopausal symptoms and mood states |

Human | oral | 10mg equol/day |

Equol treatment relieved menopausal symptoms. |

No adverse effects reported |

| The pharmacokinetic behavior of the soy isoflavone metabolite S-(−)equol and its diastereoisomer R- (+)equol in healthy adults determined by using stable-isotope- labeled tracers |

(Setchell, Zhao et al. 2009) | To compare the pharmacokinetics of S-equol and R-equol by using 13C stable- isotope-labeled tracers to facilitate the optimization of clinical studies aimed at evaluating the potential of these diastereoisomers in the prevention and treatment of estrogen and androgen dependent conditions |

Human | oral | single-bolus 20mg doses of S-equol, R- equol, and racemic equol |

R-equol has higher bioavailability than S-equol and racemic equol. Both S-equol and R-equol exhibit high systemic bioavailbility. |

Headache reported by one female subject after administration of S-equol and R-equol but not after racemic equol. |

| Single-dose and steady- state pharmacokinetic studies of S-equol, a potent nonhormonal, estrogen receptor b- agonist being developed for the treatment of menopausal symptoms |

(Jackson, Greiwe et al. 2010) | To elucidate the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of synthesized S- equol |

Human | oral | 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320 mg equol test groups |

S-equol was well tolerated by study participants and no significant drug related side effects reported. |

Nausea, paresthesia, diarrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, anorexia, nightmare, and accommodation disorder reported, although categorized as not significant |

| The Clinical Importance of the Metabolite Equol-A Clue to the Effectiveness of Soy and Its Isoflavones |

(Setchell, Brown et al. 2002) | Reviewed the importance of “bacterio-typing” individuals in soy isoflavone studies |

Human | n/a | n/a | Soy isoflavone is more efficacious in equol producers than in non producers. |

No adverse effects reported |

| Gut Bacterial Metabolism of the Soy Isoflavone Daidzein: Exploring the Relevance to Human Health |

(Atkinson, Frankenfeld et al. 2005) | Review of intestinal bacteria role in isoflavone metabolism and their relevance to individual health |

Human | oral | 3 day soy challenge, supplementing normal diets with soy |

Equol producers may be at lower risk for breast and prostate cancer. |

No adverse effects reported |

| Does the Effect of Soy Phytoestrogens on Bone in Postmenopausal Women Depend on the Equol-Producing Phenotype? |

(Vatanparast and Chilibeck 2007) | Review of the equol-producing phenotype’s implications on the effect of soy isoflavones on bone metabolism. |

Human | n/a | n/a | Equol producing ability should be considered in soy isoflavone studies. Soy milk consumption increased lumbar spine bone mineral density greater in equol- producers compared to non- producers. |

No adverse effects reported |

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1 Chemical Compounds

Genistein, daidzein and equol were purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). The sources of other materials are indicated in the experimental methods described below.

4.2 Animal Model

Colonies of non-transgenic (nonTg) mouse strain (C57BL6/129S; Gift from Dr. Frank LaFerla, University of California, Irvine) (Oddo et al., 2003) were bred and maintained at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, CA) following National Institutes of Health guidelines on use of laboratory animals and an approved protocol by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed on 12 h light/dark cycles and provided ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were genotyped routinely to confirm the purity of the colony.

4.3 In Vivo Experimental Design

To investigate the impact of OVX and phytoSERM treatments on brain mitochondrial function, 6 month old female nonTg mice were randomly assigned to one of the following four treatment groups (n=10 per group): sham ovariectomized (Sham-OVX), ovariectomized (OVX), OVX plus the S-equol phytoSERM combination (S-equol), and the OVX plus the R/S-equol phytoSERM combination (R/S-equol). Mice were bilaterally OVXed. 20 days after the OVX surgery, mice were weighed daily and subcutaneously treated for 4 consecutive days with either vehicle (OVX group), S-equol phytoSERM combination at 10mg/kg/day (S-equol group), or R/S-equol phytoSERM combination at 10mg/kg/day (R/S-equol group). Upon completion of the treatment, mice were sacrificed; tissues were harvested, processed, and stored for later analyses.

4.4 Brain Tissue Preparation and Collection

Upon completion of the study, mice were sacrificed. Cerebellum and brain stem were removed prior to further dissection. Cerebral cortex were quickly harvested and processed for crude mitochondrial isolation. Hippocampal tissues from the left hemisphere were harvested and stored for RNA isolation and custom Low-Density array analyses (LDA). Hippocampal tissues from the right hemisphere were harvested and stored for protein extraction and western blots. The left hemisphere was quickly harvested and processed for crude mitochondrial isolation.

4.5 Mitochondrial Preparation

Crude brain mitochondria were isolated from the designated cerebral cortex following our previously established protocol (Irwin et al., 2008) with minor adaptation. Briefly, the brain tissue was rapidly minced and homogenized at 4°C in mitochondrial isolation buffer (MIB) (PH 7.4), containing sucrose (320 mM), EDTA (1 mM), Tris-HCl (10 mM), and Calbiochem’s Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set I (AEBSF-HCl 500 mM, aprotonin 150 nM, E-64 1 mM, EDTA disodium 500 mM, leupeptin hemisulfate 1 mM). Single-brain homogenates were then centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in MIB, rehomogenized, and centrifuged again at 1500 × g for 5 min. The postnuclear supernatants from both centrifugations were combined and were pelleted by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 15% Percoll made in MIB and centrifuged at 31,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove most of the fatty acid contents. The resulting crude mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in MIB and stored at −80°C for later protein and enzymatic assays.

4.6 RNA isolation and Protein Extraction

Total RNA was isolated from the designated hippocampal tissues using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The quality and quantity of RNA samples were determined using the Experion RNA analysis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). RNA samples were reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −80°C for gene array analysis. For hippocampal homogenate, protein samples were extracted from designated hippocampal tissues using the Tissue Protein Extract Reagent (T-PER, Pierce, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein concentrations were determined by using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

4.7 qRT-PCR Gene Expression Analysis

Mouse mitochondrial and Alzheimer’s low density arrays (LDAs) were custom manufactured by Applied Biosystems. qRT-PCR and data analysis were conducted as previously described (Zhao et al., 2012)

4.8 Enzyme Activity Assay

PDH activity was measured by monitoring the conversion of NAD+ to NADH by following the change in absorption at 340 nm as previously described (Yao et al., 2009). Isolated brain mitochondria were dissolved in 2% CHAPS buffer to yield a final concentration of 15 μg/μl and incubated at 37°C in PDH Assay Buffer (35 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM KCN, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, (pH 7.25 with KOH), 200 mM sodium pyruvate, 2.5 mM rotenone, 4 mM sodium CoA, 40 mM TPP). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 15 mM NAD+ and the initial rate was measured. COX activity was assessed in isolated mitochondria (20 μg) using Rapid Microplate Assay kit for Mouse Complex IV Activity (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Complex I Activity assessed in isolated mitochondrial samples (5 μg) using Complex I Enzyme Activity Dipstick Assay Kit (Mitosciences, MS130-60, Eugene, OR), band density was captured and analyzed by the matching Mitosciences Dipstick reader (Mitosciences, MS1000, Eugene, OR). α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH) activity was assayed spectrophotometrically at 25°C by measuring the rate of increase of absorbance due to NADH at 340 nm as described previously (Lai and Cooper, 1986). Briefly, each assay mixture contained: 0.2 mM TPP, 2 mM NAD, 0.2 mM CoA, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 10 mM α-ketoglutarate, 130 mM HEPES-Tris pH 7.4, and 30 μg of crude cortical mitochondrial samples. The reaction was initiated by the addition of CoA and the initial rate was measured.

4.9 Western Blot Analysis

Equal amounts of proteins (20 μg/well) were loaded in each well of a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, electrophoresed with a Tris/glycine running buffer, transferred to a 0.45 m pore size polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and immunobloted with OGDH (αKDGH) antibody (1:1000, ProteinTech, Chicago, IL), COXI antibody (1:1000, Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), CVα antibody (1:1000, Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), CVβ antibody (1:1000, Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), Neprilysin (NEP) antibody (1:3000, Millipore, Temecula, CA), IDE antibody (1:2000, Millipore, Temecula, CA), PDH E1α antibody (1:1000, Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), pPDHser232 antibody (1:500, Chemicon, Ramona, CA), pPDHSer293 antibody (1:500, Chemicon, Ramona, CA), ABAD antibody (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), β-actin antibody (1:5000, Chemicon, Ramona, CA), and porin/VDAC antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody and HRP-anti-mouse antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were used as secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by Pierce SuperSignal Chemiluminescent Substrates (Thermo Scientific) and captured by Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). All band intensities were quantified using Un-Scan-it software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

4.10 Lipid Peroxidation Assay

Lipid peroxidation of hippocampal samples from individual groups were determined by assessing the levels of Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) using the TBARS assay kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) following the manufacturer’s instruction.

4.11 Metabolic Flux Analysis

Primary hippocampal neurons from day 18 (E18) embryos of female Sprague-Dawley rats were cultured on Seahorse XF-24 plates at a density of 50,000 cells/well. Neurons were grown in Neurobasal Medium +B27 supplement for 10 days prior to experiment. To investigate the impact of phytoSERM treatments on mitochondrial respiration in primary neuronal cultures, cells were treated with vehicle, S-equol phytoSERM combination (100 nM), R/S-equol phytoSERM combination (100 nM), or E2 (10 nM). The assays were conducted 24 hours post-treatment. On the day of metabolic flux analysis, media was changed to unbuffered DMEM (DMEM Base medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 31 mM NaCl, 2 mM GlutaMax; pH 7.4) and incubated at 37°C in a non-CO2 incubator for 1 h. All medium and injection reagents were adjusted to pH 7.4 on the day of assay. Using the Seahorse XF-24 metabolic analyzer, four baseline measurements of OCR (oxygen consumption rate) and ECAR (extracellular acidification rate) were sampled prior to sequential injection of mitochondrial inhibitors. Four metabolic measurements were sampled following the addition of each mitochondrial inhibitor prior to injection of the subsequent inhibitors. The mitochondrial inhibitors used were oligomycin (1 μM), FCCP (1 μM), and rotenone (1 μM). OCR and ECAR were automatically calculated and recorded by the Seahorse XF-24 software. After the assays, protein level was determined for each well to confirm equal cell density per well.

4.12 Statistical Analysis

Statistically significant differences between groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis.

Highlights.

-

▶

Potentiation of mitochondrial bioenergetics by S- and R/S-equol phytoSERMs in vitro.

-

▶

Up-regulation of bioenergetic enzyme activity by S- and R/S-equol phytoSERMs in vivo.

-

▶

Reduction of lipid peroxidation by S- and R/S-equol phytoSERMs in vivo.

-

▶

Similar gene expression profile by S- and R/S-equol phytoSERMs.

-

▶

No uterotrophic side-effect of S- or R/S-equol phytoSERMs in vivo.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant 1R01AG033288.

Abbreviations

- OCR

Oxygen Consumption Rate

- ECAR

Extra-cellular Acidification Rate

- SERM

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator

- OXPHOS

Oxidative Phosphorylation

- Aβ

amyloid β

- PDH

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase

- αKGDH

α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase

- COX

Cytochrome c oxidase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akaza H, Miyanaga N, Takashima N, Naito S, Hirao Y, Tsukamoto T, Fujioka T, Mori M, Kim WJ, Song JM, Pantuck AJ. Comparisons of percent equol producers between prostate cancer patients and controls: case-controlled studies of isoflavones in Japanese, Korean and American residents. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:86–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthana S, Brinton RD, Henderson VW, McEwen BS, Morrison JH, Schmidt PJ. Frontiers proposal. National Institute on Aging “bench to bedside: estrogen as a case study”. Age (Dordr) 2009;31:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C, Frankenfeld CL, Lampe JW. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone daidzein: exploring the relevance to human health. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:155–70. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF. Mitochondria take center stage in aging and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:495–505. doi: 10.1002/ana.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD. The healthy cell bias of estrogen action: mitochondrial bioenergetics and neurological implications. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:529–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD. Estrogen-induced plasticity from cells to circuits: predictions for cognitive function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:212–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NM, Belles CA, Lindley SL, Zimmer-Nechemias LD, Zhao X, Witte DP, Kim MO, Setchell KD. The chemopreventive action of equol enantiomers in a chemically induced animal model of breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:886–93. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA. Phytoestrogens. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:225–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GE, Chen HL, Xu H, Qiu L, Xu Z, Denton TT, Shi Q. Deficits in the mitochondrial enzyme alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase lead to Alzheimer’s disease-like calcium dysregulation. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1121, e13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ER, Liu D. Anti-diabetic functions of soy isoflavone genistein: mechanisms underlying its effects on pancreatic beta-cell function. Food Funct. 2012 doi: 10.1039/c2fo30199g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl MA, Van Veldhuizen PJ, Thrasher JB. Effects of soy phytoestrogens on the prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:216–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopaul R, Knaggs HE, Lephart ED. Biochemical investigation and gene analysis of equol: a plant and soy-derived isoflavonoid with antiaging and antioxidant properties with potential human skin applications. Biofactors. 2012;38:44–52. doi: 10.1002/biof.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen MK, Ludke A, Araujo AS, Mendes RH, Fernandes TG, Mandarino JM, Llesuy S, Vogt de Jong E, Bello-Klein A. Antioxidant characterization of soy derived products in vitro and the effect of a soy diet on peripheral markers of oxidative stress in a heart disease model. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90:1095–103. doi: 10.1139/y2012-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CB. Women’s concerns with hormone replacement therapy--compliance issues. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:157S–160S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RW, Yao J, Hamilton RT, Cadenas E, Brinton RD, Nilsen J. Progesterone and estrogen regulate oxidative metabolism in brain mitochondria. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3167–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata N, Melby MK, Mizuno S, Watanabe S. New equol supplement for relieving menopausal symptoms: randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Japanese women. Menopause. 2009;16:141–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818379fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RL, Greiwe JS, Desai PB, Schwen RJ. Single-dose and steady-state pharmacokinetic studies of S-equol, a potent nonhormonal, estrogen receptor - agonist being developed for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2010:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jou HJ, Wu SC, Chang FW, Ling PY, Chu KS, Wu WH. Effect of intestinal production of equol on menopausal symptoms in women treated with soy isoflavones. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JC, Cooper AJ. Brain alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex: kinetic properties, regional distribution, and effects of inhibitors. J Neurochem. 1986;47:1376–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lateef A, Khan AQ, Tahir M, Khan R, Rehman MU, Ali F, Hamiza OO, Sultana S. Androgen deprivation by flutamide modulates uPAR, MMP-9 expressions, lipid profile, and oxidative stress: amelioration by daidzein. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Alzheimer’s APP mangles mitochondria. Nat Med. 2006;12:1241–3. doi: 10.1038/nm1106-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Sullivan JC, Schreihofer DA. Dietary genistein and equol (4′, 7 isoflavandiol) reduce oxidative stress and protect rats against focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R871–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00031.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee PJ, Raschke M, Steiner C, Duffin JG, Pool-Zobel BL, Jokela T, Wahala K, Rowland IR. Equol: a comparison of the effects of the racemic compound with that of the purified S-enantiomer on the growth, invasion, and DNA integrity of breast and prostate cells in vitro. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:232–42. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5402_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira PI, Harris PL, Zhu X, Santos MS, Oliveira CR, Smith MA, Perry G. Lipoic acid and N-acetyl cysteine decrease mitochondrial-related oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease patient fibroblasts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:195–206. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthyala RS, Ju YH, Sheng S, Williams LD, Doerge DR, Katzenellenbogen BS, Helferich WG, Katzenellenbogen JA. Equol, a natural estrogenic metabolite from soy isoflavones: convenient preparation and resolution of R- and S-equols and their differing binding and biological activity through estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:1559–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen J, Irwin RW, Gallaher TK, Brinton RD. Estradiol in vivo regulation of brain mitochondrial proteome. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14069–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Perry G, Aliev G, Hirai K, Takeda A, Balraj EK, Jones PK, Ghanbari H, Wataya T, Shimohama S, Chiba S, Atwood CS, Petersen RB, Smith MA. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:759–67. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–21. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer L, Cadenas E. Oxidants and antioxidants revisited. New concepts of oxidative stress. Free Radic Res. 2007;41:951–2. doi: 10.1080/10715760701490975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK, Berry DA. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1670–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson TE, Simpkins JW. R- and S-Equol have equivalent cytoprotective effects in Friedreich’s Ataxia. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;13:12. doi: 10.1186/2050-6511-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Flavonoids and cancer prevention: a review of the evidence. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;31:206–38. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2012.702534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer DA, Redmond L. Soy phytoestrogens are neuroprotective against stroke-like injury in vitro. Neuroscience. 2009;158:602–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Borriello SP, Hulme P, Kirk DN, Axelson M. Nonsteroidal estrogens of dietary origin: possible roles in hormone-dependent disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40:569–78. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/40.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD. Phytoestrogens: the biochemistry, physiology, and implications for human health of soy isoflavones. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1333S–1346S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1333S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Brown NM, Lydeking-Olsen E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol-a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J Nutr. 2002;132:3577–84. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Clerici C, Lephart ED, Cole SJ, Heenan C, Castellani D, Wolfe BE, Nechemias-Zimmer L, Brown NM, Lund TD, Handa RJ, Heubi JE. S-equol, a potent ligand for estrogen receptor beta, is the exclusive enantiomeric form of the soy isoflavone metabolite produced by human intestinal bacterial flora. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1072–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Cole SJ. Method of defining equol-producer status and its frequency among vegetarians. J Nutr. 2006;136:2188–93. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.8.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Zhao X, Jha P, Heubi JE, Brown NM. The pharmacokinetic behavior of the soy isoflavone metabolite S-(−)equol and its diastereoisomer R-(+)equol in healthy adults determined by using stable-isotope-labeled tracers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1029–37. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Clerici C. Equol: history, chemistry, and formation. J Nutr. 2010a;140:1355S–62S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.119776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Clerici C. Equol: pharmacokinetics and biological actions. J Nutr. 2010b;140:1363S–8S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.119784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Xu H, Yu H, Zhang N, Ye Y, Estevez AG, Deng H, Gibson GE. Inactivation and reactivation of the mitochondrial alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17640–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkaruk S, Carreau C, Flouriot G, Bennetau-Pelissero C, Potier M. Comparative effects of R- and S-equol and implication of transactivation functions (AF-1 and AF-2) in estrogen receptor-induced transcriptional activity. Nutrients. 2010;2:340–54. doi: 10.3390/nu2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society NAM. The role of soy isoflavones in menopausal health: report of The North American Menopause Society/Wulf H. Utian Translational Science Symposium in Chicago, IL (October 2010) Menopause. 2011;18:732–53. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821fc8e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanczyk FZ, Hapgood JP, Winer S, Mishell DR., Jr. Progestogens Used in Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy: Differences in Their Pharmacological Properties, Intracellular Actions, and Clinical Effects. Endocr Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama S, Ueno T, Masaki K, Shimizu S, Aso T, Shirota T. The cross-sectional study of the relationship between soy isoflavones, equol and the menopausal symptoms in Japanese women. The Journal of the Japanese Menopause Society. 2007;15:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vatanparast H, Chilibeck PD. Does the Effect of Soy Phytoestrogens on Bone in Postmenopausal Women Depend on the Equol-Producing Phenotype? Nutrition Reviews. 2007;65:294–299. doi: 10.1301/nr.2007.jun.294-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vina J, Borras C, Gambini J, Sastre J, Pallardo FV. Why females live longer than males? Importance of the upregulation of longevity-associated genes by oestrogenic compounds. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2541–5. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale DC, Piazza C, Melilli B, Drago F, Salomone S. Isoflavones: estrogenic activity, biological effect and bioavailability. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s13318-012-0112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Irwin RW, Zhao L, Nilsen J, Hamilton RT, Brinton RD. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14670–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903563106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Chen S, Mao Z, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose treatment induces ketogenesis, sustains mitochondrial function, and reduces pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Irwin R, Chen S, Hamilton R, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. Ovarian hormone loss induces bioenergetic deficits and mitochondrial beta-amyloid. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1507–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee S, Burdock GA, Kurata Y, Enomoto Y, Narumi K, Hamada S, Itoh T, Shimomura Y, Ueno T. Acute and subchronic toxicity and genotoxicity of SE5-OH, an equol-rich product produced by Lactococcus garvieae. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:2713–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Sancheti H, Cadenas E. Silencing of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase impairs cellular redox homeostasis and energy metabolism in PC12 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:401–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Brinton RD. WHI and WHIMS follow-up and human studies of soy isoflavones on cognition. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:1549–64. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.11.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Mao Z, Brinton RD. A select combination of clinically relevant phytoestrogens enhances estrogen receptor beta-binding selectivity and neuroprotective activities in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2009;150:770–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Mao Z, Schneider LS, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor beta-selective phytoestrogenic formulation prevents physical and neurological changes in a preclinical model of human menopause. Menopause. 2011;18:1131–42. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182175b66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Morgan TE, Mao Z, Lin S, Cadenas E, Finch CE, Pike CJ, Mack WJ, Brinton RD. Continuous versus cyclic progesterone exposure differentially regulates hippocampal gene expression and functional profiles. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Z Y, Ma F, Li G, Wang P. Anti-invasion effects of R- and S-enantiomers of equol on prostate cancer PC3, DU145 cells. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2011;40:423–5. 430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler RG. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:183–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]