Abstract

Background

Cutaneous melanoma continues to increase in incidence in many countries, and intentional tanning is a risk factor for melanoma. The aim of this study was to understand how melanoma risk factors, perceived threat, and preferences for a suntan relate to intentional tanning.

Methods

Self-report data were collected on behalf of GenoMEL (www.genomel.org) from members of the general population using an online survey. A total of 8,178 individuals successfully completed at least 80% of the survey, with 72.8% of respondents from Europe, 12.1% from Australia, 7.1% from the USA, 2.5% from Israel, and 5.5% from other countries.

Results

Seven percent of respondents had previously been diagnosed with melanoma and 8% had at least one first-degree relative with a previous melanoma. Overall, 70% of the respondents reported some degree of intentional tanning during the past year, and 38% of respondents previously diagnosed with melanoma had intentionally tanned. Total number of objective risk factors was positively correlated with perceived risk of melanoma (correlation coefficient (ρ)=0.27), and negatively correlated with intentional tanning (ρ=−0.16). Preference for a dark suntan was the strongest predictor of intentional tanning (regression coefficient (β)=0.35, p<0.001), even in those with a previous melanoma (β=0.33, p<0.01).

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of participants reported having phenotypic and behavioural risk factors for melanoma. The preference regarding suntans seemed more important in the participants’ decision to intentionally tan than their perceived risk of developing melanoma, and this finding was consistent among respondents from different countries. The drive to sunbathe in order to tan appears to be a key psychological factor to be moderated if melanoma incidence is to be reduced.

Keywords: Intentional tanning; Sunbathing, Suntan; Perceived threat; Melanoma; Risk factors; Familial risk

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma has increased worldwide in fair-skinned peoples in the last few decades1. A number of melanoma risk factors have been identified such as propensity of the skin to sunburn after exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation2, light hair and eye colour, freckles, number of melanocytic naevi3, dysplastic naevi4, solar keratoses,2, 5 and genotype6. Exposure to intermittent, intense sunlight (e.g. as a result of intentional tanning) has been suggested as the most important preventable risk factor2, 7, 8. In order to reduce melanoma incidence it is therefore imperative to understand motives for intentional tanning, as well as the ways in which individuals balance the consequences of intentional tanning against their perceptions of personal vulnerability or risk.

Theories and methods developed within the behavioural and social sciences can make valuable contributions to our understanding of behaviours relevant to melanoma prevention and give important guidance on how interventions should be constructed to promote behavioural change. According to some social-cognition models in health psychology, peoples’ perceived threat i.e. beliefs about the outcomes associated with specific health behaviours and perceptions of personal risk or vulnerability to a particular health threat, are predictive of behaviour9,10, 11. Of particular importance in these models are perceptions of risk and worry about the consequences of a particular health threat. It is suggested that people who perceive themselves to be at risk of a disease, believe that the disease is harmful, and worry about developing the disease are more likely to take precautions to lower their risk.

Although perceptions of risk may promote sensible behaviours, individuals may fail to adopt those behaviours because of certain ’barriers’. For example, individuals may perceive the inconvenience or cost associated with sunscreen use as a barrier to sun protection. Another barrier might be the loss of beneficial effects of sun exposure such as a tan or the enjoyment of intentional tanning consequent upon sun protection. For many, a suntan is representative of physical and emotional health and attractiveness12–14. The preference for a suntan as a motivator for intentional tanning has been frequently reported15–22, even among individuals with a familial susceptibility to melanoma23.

The present study describes the relationship between intentional tanning, reported risk factors for melanoma, perceived threat and preferred level of suntan among individuals who participated in a web-based survey. The study was carried out with the intent of informing the development of web-based educational materials, and so was guided by two main research questions:

Are melanoma risk factors, perceived threat and tanning preferences associated with people’s decision to intentionally expose themselves to UV radiation so as to tan?

Does perceived threat moderate the impact of melanoma risk factors on frequency of intentional tanning?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The sample was comprised of members of the general population recruited between January 2007 and September 2008 using a web-based survey. Recruiting centres were located in 12 countries (Australia, Germany, Israel, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the USA) participating in the melanoma genetics consortium, GenoMEL (www.genomel.org). In each participating country, recruitment was encouraged by press releases (in conjunction with cancer charities, university press offices, national authorities responsible for UV radiation and/or public health issues), mailed flyers, e-mail ‘cascades’ (through personal e-mail address lists, university lists, company lists and so forth). Links from other websites were also used. Potential participants were encouraged to visit the GenoMEL website (www.genomel.org), where they could find more information regarding the study and a questionnaire available in ten different languages. The study was approved by relevant ethical bodies. Individuals aged less than 16 years were advised to discuss their participation with an adult before completing the questionnaire.

Measures

A web-based questionnaire was developed for data collection via the GenoMEL website. It had a flash based interface feeding into a single MYSQL database (technical realisation by New Knowledge Directorate Ltd www.nkd.org.uk). The self-report questionnaire was purposely designed for the study in English, although many of the individual items previously had been used and some validated and tested for reliability24, 25. Questionnaire translation was carried out by two independent bilingual professionals, and additionally tested for clarity and readability by a number of lay people. Efforts were made to ensure that the survey was as user friendly as possible. A list of the questionnaire items can be obtained on request from GenoMEL (info@genomel.org). In addition to questions about age and gender the questionnaire consisted of three major sections: objective melanoma risk factors, behavioural risk factors, and motivational/attitudinal factors.

Objective risk factors were assessed via multiple-choice items eliciting data on hair colour (red/blond/light brown/dark brown/black), freckling (none/a few/many), eye colour (blue/green/gray/green-gray/blue-gray/brown), skin colour (based on 7 pictures of hands with varying levels of pigmentation), skin type (Fitzpatrick’s skin type classification26), personal and family history of melanoma (defined as one or more affected first-degree relatives), experience of severe sunburns before the age of 16, and number of large moles (larger than 6 mm (or ¼ inch)) (none/1–2/3–5/6–10/more than 10). These items were also used to calculate a risk factor score based on the total number of risk factors. The total score was calculated by categorising all participants into dichotomous variables based on all the above mentioned risk factors assigning individuals as either ‘having’ (1) or ‘not having’ (0) each specific risk factor. Those who were categorised into ‘having’ a risk factor were those who: had red or blond hair colour, had any freckles, had blue, green, gray, green-gray, or blue-gray eye colour, had light or very light pigmentation, had skin type I or II according to Fitzpatrick’s skin type classification, had at least one first degree relative that have had a melanoma, had previously been diagnosed with a melanoma, had experienced at least one severe sunburn before the age of 16, and reported having at least 1 or 2 large moles. The numbers of risk factors were then summated, resulting in a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 9. In addition to these objective risk factors, participants were categorised into five regions of residence based on latitude. The categories were from high latitude to lower: Northern Europe between N55–69° (Sweden N55–69°, Latvia N56–58°), Northern/Central Europe between N49–59° (Germany N50–55°, Poland N49–55°, the UK N50–59°, the Netherlands N51–53.5°), Southern Europe/North USA between N36–50° (Spain N36–43.5°, Italy N38–47°, Slovenia N46.5–47°, the Northern states in USA N40–50°), West Asia/Southern USA/Southern Australia between N30–40° and S29–43° (Israel N30–35°, the Southern States in the USA N30–40°, the Southern and West States in Australia S29–43°), and Northern Australia between S10–29° (the northern states in Australia S10–29°).

Behavioural risk factors were assessed by items regarding sun exposure, sunburn, sun protective behaviour, and vacations to sunny locations. In this paper, we report the frequency of intentional tanning during activities such as sunbathing and the use of artificial tanning devices. Three questions were used to measure intentional tanning: frequency of sunbathing in the home country, frequency of sunbathing abroad, and frequency of sunbed use during the past year. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency on a scale with six response options (0: never, 1: 1–3 times, 2: 4–10 times, 3: 11–30 times, 4: 31–60 times, 5: 61 times or more). A total score (range 0 to 15) that summed responses to all three behavioural questions was used for this study.

Motivational/attitudinal factors included perceived threat and preferred level of tan. Perceived threat was assessed via eight items covering different aspects of melanoma risk such as perceived vulnerability to melanoma, perceived severity of melanoma, and worry about getting melanoma. The measures of perceived threat had a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of 0.76, suggesting good internal consistency. Preferred level of tan was assessed using computer-generated pictures of people with varying levels of suntan and respondents were asked to indicate the suntan level they most preferred, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Computer-generated pictures of people with varying levels of suntan used to assess respondents preferred level of tan.

Statistical analysis

To examine associations between risk factors, perceived threat, and intentional tanning, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to examine associations between continuous and ordinal variables, while t-tests were used when the predictor variable was binary. One-way analysis of variance was used when the predictor variable had three or more categories. Adjusted means of intentional tanning for each country were calculated using, a general linear model (GLM); and age, gender, skin type, hair colour, family history of melanoma, previous melanoma, experience of sunburn before the age of 16, number of freckles, and number of large moles were adjusted as covariates in the model. Hierarchical multivariable regression analyses were used to examine the relative importance of age, gender, latitude of residence, number of objective risk factors, perceived threat and preferred level of tan with intentional tanning. In the hierarchical models, age, gender, latitude of residence, and number of melanoma risk factors were entered at the first step; perceived threat were entered at the second step, and preferred level of suntan was entered at the third step; interaction terms were entered in the final step. Given the multiple associations examined and the large sample size, an alpha level of 0.01 was used to determine statistical significance of all analyses. Data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0.

RESULTS

Between January 2007 and September 2008, a total of 11,403 individuals accessed the questionnaire: 220 respondents were excluded due to age (younger than 15 or older than 86 years) or missing data on gender. Of the remaining 11,183 participants, 8,178 (73.1%) successfully completed at least 80% of the questions, with 72.8% of respondents from Europe, 12.1% from Australia, 7.1% from the USA, 2.5% from Israel, and 5.5% from other countries. Demographic characteristics and self-reported objective risk factors are presented separately by country in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age, gender and objective melanoma risk factors from respondents in the 12 recruiting countries.

| Sweden | Latvia | UK | Netherlands | Germany | Poland | Slovenia | Spain | Italy | Israel | USA | Australia | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of participants | 804 | 733 | 846 | 960 | 669 | 870 | 132 | 343 | 596 | 203 | 596 | 989 | 452 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Men (%) | 39.9 | 20.6 | 24.6 | 25.1 | 31.5 | 10.8 | 70.5 | 29.2 | 36.4 | 26.6 | 20.1 | 24.9 | 30.1 |

| Women (%) | 60.1 | 79.4 | 75.4 | 74.9 | 68.5 | 89.2 | 29.5 | 70.8 | 63.6 | 73.4 | 79.9 | 75.1 | 69.9 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 38.1 (13.1) | 32.5 (12.5) | 37.7 (13.2) | 38.7 (14.2) | 40.7 (13.2) | 30.2 (8.5) | 40.1 (12.0) | 36.8 (12.0) | 37.4 (10.5) | 32.7 (14.6) | 42.5 (12.6) | 35.0 (14.0) | 36.3 (12.5) |

| Hair colour | |||||||||||||

| Black/Brown (%) | 64.7 | 79.0 | 79.1 | 61.0 | 62.0 | 71.8 | 80.3 | 88.6 | 88.2 | 82.3 | 73.3 | 76.2 | 80.5 |

| Blond (%) | 30.7 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 33.0 | 32.2 | 26.2 | 18.9 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 14.3 | 18.8 | 16.5 | 16.2 |

| Red (%) | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 3.3 |

| Fitzpatrick skin type | |||||||||||||

| I (%) | 1.2 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 1.8 | 5.1 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 12.0 | 6.2 |

| II (%) | 26.6 | 20.2 | 32.5 | 25.9 | 24.9 | 22.5 | 31.1 | 24.5 | 26.8 | 52.2 | 35.3 | 34.6 | 25.9 |

| III (%) | 66.2 | 70.8 | 57.7 | 68.8 | 65.2 | 58.5 | 62.9 | 60.9 | 61.9 | 28.1 | 48.8 | 50.3 | 60.8 |

| IV (%) | 6.0 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 16.8 | 3.0 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 5.4 | 3.1 | 7.1 |

| Presence of freckles | |||||||||||||

| None (%) | 58.5 | 53.9 | 36.8 | 47.6 | 50.4 | 45.4 | 44.7 | 19.0 | 60.9 | 40.9 | 29.7 | 27.5 | 47.1 |

| A few (%) | 31.2 | 40.4 | 48.5 | 41.0 | 39.6 | 39.4 | 44.7 | 60.0 | 33.0 | 41.4 | 45.4 | 52.2 | 37.6 |

| Many (%) | 10.3 | 5.7 | 14.7 | 11.4 | 10.0 | 15.2 | 10.6 | 21.0 | 6.1 | 17.7 | 24.9 | 20.3 | 15.3 |

| Number of large mole (>6mm) | |||||||||||||

| None (%) | 38.6 | 50.7 | 42.9 | 40.1 | 24.8 | 36.8 | 32.6 | 38.5 | 29.4 | 34.5 | 37.2 | 35.4 | 38.7 |

| 1–2 (%) | 33.0 | 34.8 | 35.2 | 32.2 | 28.0 | 33.6 | 34.1 | 33.5 | 32.7 | 34.0 | 31.0 | 33.4 | 31.0 |

| >=3 (%) | 28.4 | 14.3 | 21.9 | 27.7 | 47.2 | 29.6 | 33.3 | 28.0 | 37.9 | 31.5 | 31.8 | 30.6 | 30.3 |

| Sunburn before age 16 | |||||||||||||

| Never (%) | 12.8 | 35.7 | 27.2 | 32.6 | 18.7 | 30.4 | 14.4 | 34.4 | 33.9 | 14.9 | 14.2 | 10.4 | 23.7 |

| 1–3 times (%) | 48.6 | 49.9 | 59.7 | 56.5 | 59.2 | 55.7 | 49.6 | 48.4 | 50.1 | 47.0 | 47.5 | 54.6 | 51.6 |

| Almost every summer (%) | 38.6 | 14.4 | 13.1 | 10.9 | 22.1 | 13.9 | 36.0 | 17.2 | 16.0 | 38.1 | 38.3 | 35.0 | 24.7 |

| Family history of melanoma (%) | 4.4 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 9.4 | 6.7 | 2.3 | 5.3 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 12.3 | 18.6 | 17.2 | 6.2 |

| Previously melanoma (%) | 1.0 | 0.4 | 7.6 | 3.9 | 15.7 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 8.9 | 4.9 | 28.1 | 6.0 | 6.9 |

| Total number of risk factors, mean (SD) | 4.21 (1.60) | 3.73 (1.43) | 4.21 (1.73) | 4.13 (1.79) | 4.50 (1.69) | 3.86 (1.63) | 4.10 (1.62) | 3.74 (1.66) | 3.58 (1.72) | 4.37 (1.32) | 4.87 (2.02) | 4.71 (1.84) | 3.83 (1.83) |

Melanoma risk factors

The mean number of melanoma risk factors was 4.2 (SD=1.8). Seven percent of respondents had previously been diagnosed with a melanoma and 8% reported at least one first-degree relative with a previous melanoma. The mean age for those reporting a previous melanoma diagnosis was 45.5 years (SD=11.9).

Intentional tanning

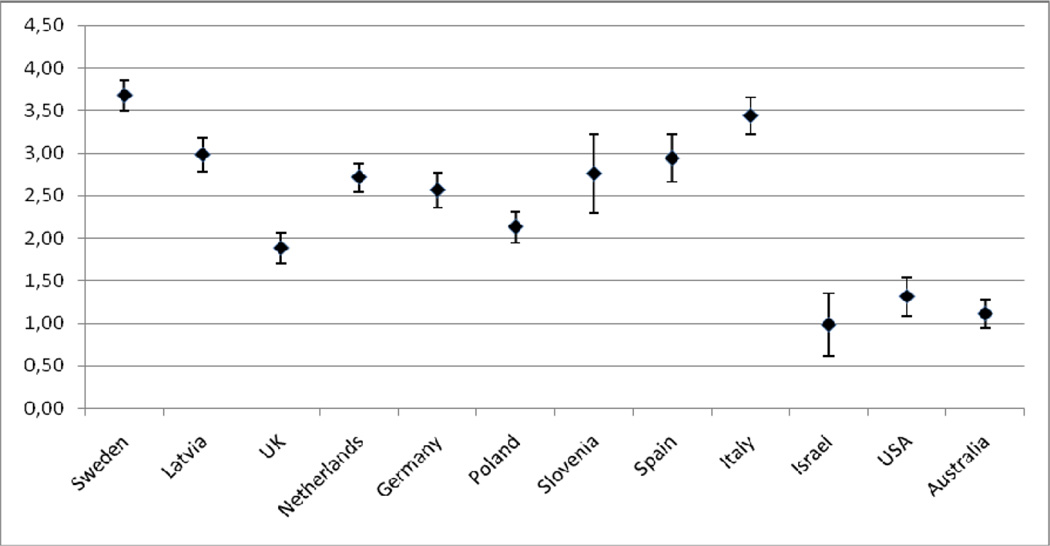

Overall, 70.3% of respondents reported some degree of intentional tanning in the past year, and among people with a previous melanoma the proportion was 38.2%. After adjusting for age, gender, skin type, hair colour, skin colour, eye colour, and number of moles and freckles, family history of melanoma, and experience of a previous melanoma, mean intentional tanning scores varied considerably between respondents in different countries (Figure 2). There were significant differences in intentional tanning between different latitude regions (F5, 8140 = 101.99, p < 0.001), and pair-wise comparisons showed that respondents in all European countries reported significantly higher levels of intentional sun exposure than those living in non-European countries (p < 0.001). Further, pair-wise comparisons showed that respondents from Sweden and Italy reported intentional tanning at a significantly higher frequency than in other countries (p<0.001), while respondents in the UK and Poland reported a significantly lower frequency of intentional tanning than the rest of Europe (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Adjusted mean scores of intentional tanning (min=0, max=15) and their 99% confidence intervals by country of residence (adjusted for gender, age, skin type, hair colour, experience of sunburn before the age of 16, number of freckles, number of moles, family history of melanoma, and experience of own previous melanoma).

Associations between risk factors, perceived threat, preferred level of suntan, and intentional tanning

Women reported a greater perceived susceptibility to melanoma than did men, but women also reported a greater desire for a deeper tan and more frequent intentional tanning (p<0.001 for both comparisons, Table 2). Respondents under the age of 25 were less likely to perceive risk and more likely to prefer a deeper tan; they also reported more frequent intentional tanning than older people. Overall, respondents with red hair, freckles, low Fitzpatrick skin type, those who had experienced sunburn before the age of 16 years, had a family history of melanoma or a previous melanoma, and/or large naevi, reported higher perceived threat, lighter tan preference, and less intentional tanning (p<0.001 for all comparisons).

Table 2.

Relationship between age, gender and objective melanoma risk factors, and perceived threat, preference for a tan, and score of intentional tanning.

| Perceived threat (min=0, max=4) |

Preferred level of tan (min=0, max=4) |

Intentional tanning (min=0, max=15) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Sig. | Mean (SD) | Sig. | Mean (SD) | Sig. | |

| Gender | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Men | 2.69 (0.56) | 2.71 (0.76) | 2.20 (2.22) | |||

| Women | 2.84 (0.76) | 2.78 (0.77) | 2.44 (2.29) | |||

| Age | p < 0.001a | p < 0.001b | p < 0.001c | |||

| <25 | 2.66 (0.53) | 2.85 (0.77) | 2.93 (2.39) | |||

| 25–30 | 2.71 (0.51) | 2.78 (0.74) | 2.49 (2.26) | |||

| 31–40 | 2.75 (0.54) | 2.78 (0.73) | 2.31 (2.16) | |||

| 41–50 | 2.77 (0.58) | 2.73 (0.81) | 2.20 (2.30) | |||

| >50 | 2.71 (0.57) | 2.63 (0.78) | 1.83 (2.14) | |||

| Hair colour | p < 0.001d | p < 0.001d | p < 0.001d | |||

| Black/Brown | 2.77 (0.53) | 2.79 (0.75) | 2.39 (2.25) | |||

| Blond | 2.83 (0.54) | 2.72 (0.78) | 2.53 (2.40) | |||

| Red | 3.07 (0.58) | 2.50 (0.87) | 1.54 (1.87) | |||

| Fitzpatrick skin type | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||

| III/IV | 2.73 (0.52) | 2.90 (0.69) | 2.78 (2.35) | |||

| I/II | 2.95 (0.54) | 2.49 (0.84) | 1.55 (1.87) | |||

| Presence of freckles | p < 0.001e | p < 0.001e | p < 0.001e | |||

| None | 2.69 (0.53) | 2.83 (0.75) | 2.60 (2.30) | |||

| A few | 2.83 (0.51) | 2.74 (0.77) | 2.32 (2.26) | |||

| Many | 3.06 (0.51) | 2.64 (0.79) | 1.82 (2.16) | |||

| Sunburn before age 16 | p < 0.001f | p < 0.001g | p < 0.001f | |||

| Never | 2.63 (0.52) | 2.86 (0.72) | 2.68 (2.35) | |||

| 1–3 times | 2.80 (0.51) | 2.73 (0.76) | 2.36 (2.23) | |||

| Almost every summer | 2.99 (0.54) | 2.68 (0.82) | 2.10 (2.34) | |||

| Number of large mole (>6mm) | p < 0.001h | p < 0.001i | p < 0.001j | |||

| None | 2.69 (0.53) | 2.83 (0.75) | 2.60 (2.30) | |||

| 1–2 | 2.83 (0.51) | 2.74 (0.77) | 2.32 (2.26) | |||

| >=3 | 3.06 (0.52) | 2.64 (0.79) | 1.82 (2.16) | |||

| Family history of melanoma | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||

| No | 2.76 (0.52) | 2.78 (0.76) | 2.44 (2.28) | |||

| Yes | 3.20 (0.51) | 2.59 (0.80) | 1.68 (2.10) | |||

| Previous melanoma | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||

| No | 2.75 (0.51) | 2.78 (0.76) | 2.47 (2.28) | |||

| Yes | 3.46 (0.45) | 2.54 (0.88) | 1.10 (1.83) | |||

| Total number of risk factors | p < 0.001k | p < 0.001k | p < 0.001k | |||

| 0–3 | 2.63 (0.50) | 2.92 (0.69) | 2.75 (2.32) | |||

| 4–5 | 2.80 (0.51) | 2.73 (0.76) | 2.46 (2.31) | |||

| > 5 | 3.09 (0.53) | 2.53 (0.82) | 1.63 (2.04) | |||

Age group ‘<25’ had sig. lower score than the other age groups;

Age group ‘> 50‘ had sig. lower score than age groups ‘<25’, ’25–30’ and ’31–40’, and age group ’41–50’ had sig. lower score than age groups ’<25’;

Age groups ‘<25‘ had sig. higher score than the other age groups, and age group ’>50’ had lower score that the other age groups;

Respondents with red hair colour had statistically significantly different score that those with blond or darker hair colour;

Risk perception increased significantly with increasing number of freckling, and intentional tanning preference and intentional tanning frequency increased;

Risk perception increased significantly with increasing number of childhood sunburns, and intentional tanning frequency increased;

Respondents with no history of childhood sunburn scored significantly higher on preferred level of suntan;

There was a significant linear trend for number of moles and risk perception;

Respondents with no moles scored significantly higher on preferred level of suntan than those with three or more moles;

Respondents with three or more moles scored significantly lower on the scale measuring frequency of intentional tanning;

There was a significant linear trend for total number of risk factors and risk perception, tan-preference and tanning.

Differences in perceived threat and preference for a tan in different countries are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimated means with 99% CI for perceived threat and preferred level of suntan by repondent’s country of residence adjusted for age, gender, skin type, hair colour, experience of sunburn before the age of 16, number of freckles, number of moles, family history of melanoma, and experience of own previous melanoma.

| Perceived threat (min=0, max=4) |

Preferred level of tan (min=0, max=4) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted mean (99% CI) | Sig.a | Adjusted mean (99% CI) | Sig.a | |

| Country of residence | ||||

| Sweden (SW) | 2.59 (2.54–2.63) | <UK, GE, SP, IT, IS, USA, AU | 3.11 (3.04–3.18) | >LA, UK, NE, GE, PO, SL, SP, IT, IS, USA, AU |

| Latvia (LA) | 2.51 (2.47–2.55) | <UK, PO, SP, IT, IS, USA, AU | 2.86 (2.79–2.93) | >UK, GE, SL, IS, USA, AU & <SW |

| UK | 2.73 (2.69–2.77) | >SW, LA & <GE, IT, USA, AU | 2.62 (2.55–2.69) | <SW, LA, NE, PO, SP, IT |

| Netherlands (NL) | 2.55 (2.51–2.58) | <UK, GE, PO, SP, IT, IS, USA, AU | 2.76 (2.70–2.83) | >UK, IS, USA, USA, AU & <SW, SP, IT |

| Germany (GE) | 2.82 (2.77–2.86) | >SW, LA, IK, NE, PO, SL, IT & <AU | 2.64 (2.56–2.71) | <SW, LA, PO, SP, IT |

| Poland (PO) | 2.65 (2.61–2.69) | >LA, NE & <UK, GE, SP, IT, USA, AU | 2.83 (2.76–2.90) | >UK, GE, IS, USA; AU & <SW |

| Slovenia (SL) | 2.63 (2.53–2.73) | <GE, IT, USA, AU | 2.56 (2.39–2.73) | <SW, LA, SP, IT |

| Spain (SP) | 2.72 (2.65–2.78) | >SW, LA, NE, & <IT, AU | 2.90 (2.80–3.00) | >UK, GE, SL, IS, USA, AU & <SW |

| Italy (IT) | 3.00 (2.95–3.05) | >SW, LA, UK, NE, GE, PO, SL, SP, IS, USA | 2.97 (2.89–3.05) | >UK, NE, GE, SL, IS, USA AU |

| Israel (IS) | 2.74 (2.65–2.82) | >SW, LA, NE & <IT, AU | 2.52 (2.38–2.66) | <SW, LA, NE, PO, SP, IT |

| USA | 2.84 (2.79–2.89) | >SW, LA, UK, NE, PO, SL & <IT, AU | 2.54 (2.45–2.63) | <SW, LA, NE, SP, SP, IT |

| Australia (AU) | 2.92 (2.88–2.96) | >SW, LA, UK, NE, GE, PO, SL, SP, IS | 2.55 (2.49–2.62) | <SW, LA, NE, PO, SP, IT |

Post-hoc test with pair-wise comparisons between countries with differences at the p<0.01 level.

Correlations between the number of melanoma risk factors, perceived threat, tan preference, and intentional tanning behaviour, for those with and those without a previous melanoma, are presented in Table 4. Intentional tanning and total number of risk factors were negatively correlated among those without a previous melanoma (ρ=−0.16, p<0.001), with lower levels of intentional exposure reported by those with a greater number of objective risk factors. Number of objective risk factors was positively associated with perceived risk of melanoma (ρno previous melanoma=0.27, p<0.001; ρprevious melanoma=0.20, p<0.001). The strongest correlation was found between preferred level of suntan and intentional tanning (ρno previous melanoma=0.42, p<0.001; ρprevious melanoma=0.33, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Spearman correlations between number of melanoma risk factors, perceived threat, preferred level of suntan and score of intentional tanning.

| Number of melanoma risk factors |

Perceived threat | Preferred level of suntan |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No previous melanoma | |||

| Score of intentional tanning | −0.16** | −0.07** | 0.42** |

| Number of melanoma risk factors | 0.27** | −0.20** | |

| Perceived threat | −0.03* | ||

| Previous melanoma | |||

| Score of intentional tanning | −0.10 | −0.16** | 0.33** |

| Number of melanoma risk factors | 0.20** | −0.12 | |

| Perceived threat | −0.08 |

=p < 0.01.

=p < 0.001

Determinants of intentional tanning

To examine the relative importance of the different correlates of intentional tanning, we built hierarchical multivariable regression models that included variables for host characteristics (age, gender, latitude of residence, and number of melanoma risk factors), risk perception, preferred level of sun tan, and interactions. Preliminary analyses revealed a significant interaction of melanoma history with most variables of interest. Thus, the primary analyses were conducted and reported separately for those with and those without a previous melanoma (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hierarchical multivariable regression analyses of association between perceived threat, attitudes towards a tan, and intentional tanning among people with a previous melanoma diagnosis and among those without a previous melanoma diagnosis.

| Betas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||

| Previous Melanoma | Step1 | Age | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.08 | −0.07 |

| Gender | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | ||

| Latitude of residence | −0.20** | −0.18** | −0.16* | −0.16* | ||

| Number of melanoma risk factors | −0.12 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.09 | ||

| Step 2 | Perceived threat | −0.19** | −0.19** | −0.19* | ||

| Step 3 | Preferred level of sun tan | 0.25** | 0.33** | |||

| Step 4 | Risk perception × Number of risk factors | −0.02 | ||||

| Preferred level of sun tan × Number of risk factors | −0.10 | |||||

| R2 | 0,07 | 0,11 | 0,17 | 0,17 | ||

| R2 change | 0.04** | 0,06** | 0,00 | |||

| Step | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||

| No Previous Melanoma Step | 1 Step | Age | −0.12** | −0.12** | −0.09** | −0.09** |

| Gender | 0.05** | 0.04** | 0.03 | −0.03 | ||

| Latitude of residence | −0.28** | −0.29** | −0.23** | −0.21** | ||

| Number of risk factors | −0.14** | −0.14** | −0.07** | −0.06** | ||

| Step 2 | Perceived threat | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.01 | ||

| Step3 | Preferred level of sun tan | 0.35** | 0.35** | |||

| Step 4 | Risk perception × Number of risk factors | −0.08** | ||||

| Preferred level of sun tan × Number of risk factors | −0.04* | |||||

| R2 | 0,12 | 0,12 | 0,23 | 0,24 | ||

| R2 change | 0.00 | 0,11** | 0,01** | |||

=p<0.01 &

=p<0.001

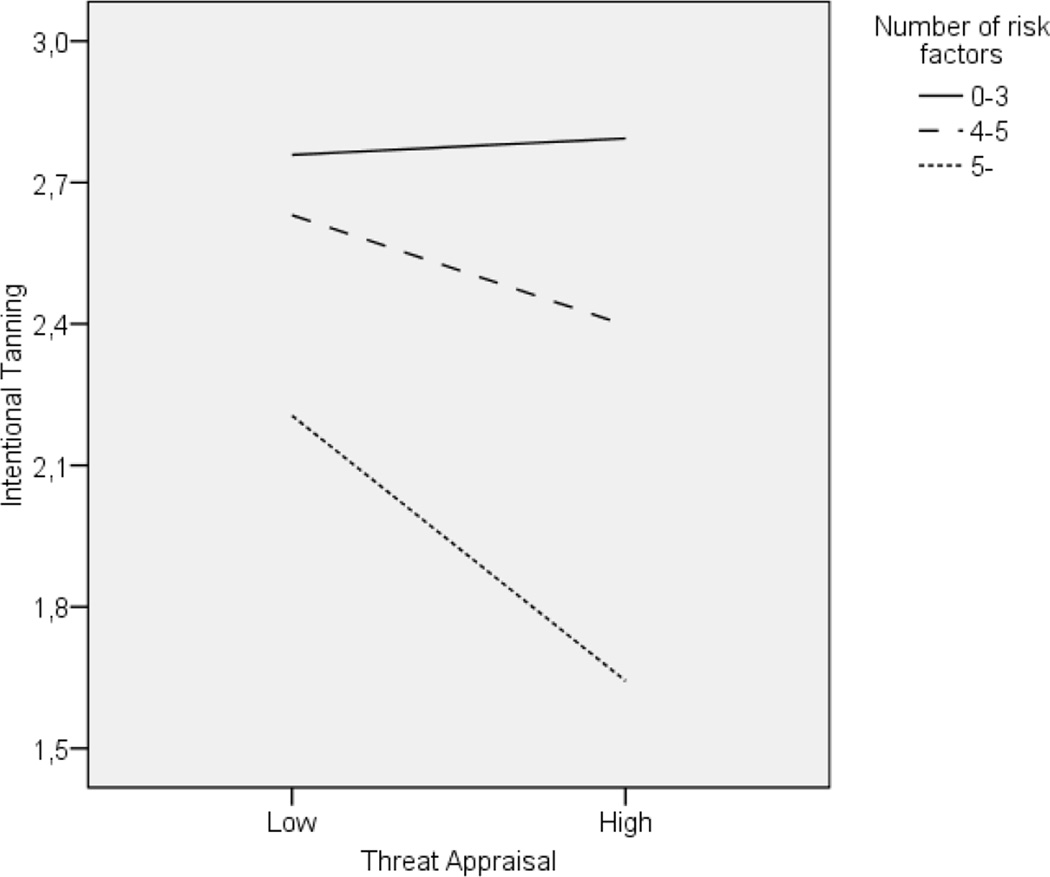

For those with a previous melanoma (n=557), the final model accounted for 17% of the variation in intentional tanning, while for those without a personal history of melanoma (n=7621), the final model accounted for 24% of the variation. Among those with a previous melanoma, greater risk perception was related to lower levels of intentional tanning, and the preferred level of tan was the strongest predictor for intentional tanning; we observed no significant interaction effects. In contrast, among those without a personal history of melanoma, the perceived risk of developing melanoma appeared to moderate the relationship between objective risk and intentional tanning. Risk perception was only associated with intentional tanning if the number of reported objective risk factors was high (β0–3 risk factors=0.02, n.s.; β4–5 risk factors=−0.08, p<0.001; β5 or more risk factors=−0.20, p<0.001). Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between risk perception and intentional tanning among respondents classified according to the number (0–3, 4–5, 5 or more) of their reported objective risk factors. High number of risk factors decreased the likelihood of intentional tanning (β = −0.08, p < 0.001), and we observed a significant interaction between risk factors and risk perception (β = −0.16, p < 0.001). Among those respondents with the higher number of melanoma risk factors, reported tanning was lower for those with higher perceived risk of melanoma compared to those with lower perceived risk.

Figure 3.

Mean levels of intentional tanning (possible range: 0–15), as a function of the interaction between objective risk (0–3, 4–5 or more than 5) and perceived threat (median split into low (<2.79) versus high (≥2.79)) among respondents with no previous experience of melanoma.

Differences in prediction of intentional tanning for countries of different latitude

For each country, we separately conducted regression analyses to examine differences in predictors of intentional tanning among respondents without a previous melanoma. In all countries, preference for a suntan was statistically significantly associated with intentional tanning, although we did note slight heterogeneity of effect (βSweden= 0.37; βLatvia= 0.34; βUK= 0.29; βNetherlands =0.34; βGermany=0.39; βPoland= 0.34; βSlovenia= 0.29; βSpain= 0.38; βItaly =−0.30; βIsrael= 0.36; βUSA= 0.32; βAustralia= 0.33; all p<0.001). However, number of melanoma risk factors was associated with intentional tanning only in Poland (β=−0.10, p<0.01), Spain (β=−0.20, p<0.001), and Australia (β=−0.11, p<0.01), and the interaction between number of risk factors and perceived threat was only significantly associated with intentional tanning in Poland (β=−0.10, p<0.01), and USA (β=−0.13, p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study focused on a sample recruited through the Internet, because this population is the target group for a planned preventative intervention. Understanding of perceptions of threat and beliefs in this population, and the processes through which risk factors and risk perceptions are associated with behaviour are key factors in the construction of this intervention. This study showed that it was possible to target a high proportion of individuals with phenotypic and behavioural risk factors for melanoma using the Internet. Many of the respondents who reported numerous melanoma risk factors and even those reporting a previous melanoma also reported frequent intentional tanning, a surprising finding given their increased risk of melanoma.

We found that women and younger people were slightly more likely to report intentional tanning, but the actual differences between age groups and gender are very small and the fact that they turn out significant is more a result of the large sample size and the clinical relevance of the difference. However, the difference found is consistent to the results of previous studies from European countries17, 22, 27–29, the USA30, 31, and Australia32. We also found women and younger individuals reported a preference for a darker suntan, although in the multivariate model, gender was no longer an important predictor of intentional tanning.

This study showed an association between melanoma risk factors and risk perception. This indicates that people are, at least to some degree, aware of their risk factors and adjust their perception of risk accordingly. However, among those without a personal history of melanoma (the large majority of respondents), risk perception did not appear to influence intentional tanning behaviours when the influence of number of risk factors was accounted for. This is contrary to some previous findings18–20, 33, 34 and is inconsistent with models of health behaviour prediction. However, the lack of association between perceived risk and UV exposure has been reported in previous research17, 35, 36. The majority of previous studies reporting an association between risk perception and intentional tanning have sampled student populations, a subset of the population that may be different in their perceptions and behavioural decisions than the general population. Interestingly, this study provides evidence for a weak but significant moderating effect of risk perception on the association between the number of reported objective risk factors and intentional tanning. Among those with few risk factors people’s risk perception did not seem to influence their intentional tanning. Individuals with higher perceived risk seemed to reduce their risk exposure if they also had a higher number of risk factors. Hence, if risk perception can be modified through appropriate education, it may also be possible to increase the proportion of people that adequately adjust their behaviour to their melanoma risk. Further, preferred level of tan was the most important predictor of intentional tanning and this preference seemed to be associated with number of melanoma risk factors. Thus, increased knowledge of melanoma risk factors might influence preferences regarding suntans and lead to a reduction of intentional tanning. It is possible that increased awareness of risk factors for melanoma will lead to an increased perception of the individual’s personal susceptibility to melanoma, an altered view of preferred level of suntan and subsequently reduced intentional tanning in the general population. Even though changing behaviour can be very difficult37, some studies focusing on information concerning personalised risks and risks related to appearance have shown promising results in changing people’s intentions to tan and use sun protection38–42. However, for such interventions to instigate long-lasting change, it may also be critical to take into account and address the powerful emotive barriers to reduced intentional tanning, such as perceptions of health and beauty associated with a tanned appearance, and the enjoyment derived from intentional tanning.

Despite some indication that risk perception influences intentional tanning, even among people with a previous melanoma, the preference for a darker tan was more important in participants’ decisions to intentionally exposure themselves to UV radiation than their perceived risk of developing a melanoma. It seems that when people make the decision to intentionally tan, the potential negative consequences of intentional tanning are outweighed by the positive consequences. People do not seem to consider intentional tanning to be a big enough threat to them to motivate avoidance. It may be the case that individuals value the more immediate consequences of tanning more than the long-term consequences. Thus, individuals may fully appreciate the fact that their tanning may result in eventual melanoma but they place so much value in the aesthetic experience of being tanned that its positive value outweighs the negative price of the future consequence. The importance of educating people about the detrimental effect of intentional tanning should be considered when constructing preventive interventions, and in particular emphasising the importance of protection among those with multiple risk factors, or a previous melanoma. But the question remains how to deal with the positive consequences of tanning behaviour.

The strategy used for recruitment of respondents in this study does not permit us to make generalisations regarding the prevalence of intentional tanning in separate countries. However, the adjusted comparisons between countries taking age, gender and melanoma risk factors into account can give some indication of regional differences in intentional tanning. It seems like people in Europe are more inclined to intentionally tan than non-Europeans. High frequencies of intentional tanning have been reported in previous studies from Europe. In a cross-national study of European students, between 69 and 99% of the respondents reported sunbathing28. Much lower prevalence has been reported for populations in the USA and Australia. In a recent large scale study from the USA among respondents of different ages, between 20 and 35% reported staying in the sun when outside on a sunny day and between 8 and 20% reported use of sunbeds31. A study from Queensland, Australia, showed that 12% of respondents aged 20–75 years reported attempting to get a suntan in the past year43. In our study we found particularly high levels of intentional tanning in Sweden and Italy. Several studies have reported on high levels of intentional tanning in Sweden15, 27, but less has been reported from Italy. In one study of Italian adolescents, between 33 and 53% reported sunbathing29. However, comparisons of prevalence of intentional tanning in different studies have limitations due to differences in the studied samples, items used for the measurement of tanning and the response format. Respondents in the UK reported particularly low level of intentional tanning, and even though the overall reason for this is unclear, one cross-national study comparing British and Italian holiday-makers’ skin cancer attitudes showed that the British scored higher than the Italians on skin cancer vigilance44. The most obvious difference between countries in this study was between respondents in Europe and the Non-European countries, and this difference cannot fully be explained by country differences in risk perception and preferred level of suntan. Despite the differences in prevalence of intentional tanning, the association between preferred suntan and intentional tanning was consistent between countries and seems to be a key psychological factor to be moderated if melanoma incidence is to be reduced.

Study strengths and limitations

One of the key strengths of the present study was the innovative use of the Internet and online survey design to reach a large number of people across a wide range of countries. The translation of the study questionnaire into 10 different languages also increased study accessibility. However, the study is not without limitations. Due to the varying recruitment strategies used in different countries, conclusions regarding differences between countries should be made with caution. Also, between 30 and 89% of survey respondents in each country were women, and the mean age of participants varied between 30.2 and 42.5 years, indicating that the present sample comprised a relatively young population, with substantial gender variability between countries. The relatively large proportion of individuals with a personal or family history of melanoma also indicates that the recruitment strategy used may have appealed to people interested in or concerned about skin cancer-related issues. Further, the cross-sectional nature of this study means that it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding causality between risk perceptions and behaviour. It does, however, give some indication of the type of individuals that it may be beneficial to target with information and questions regarding melanoma prevention using the Internet. As high levels of risk exposure were found in this study, future prevention efforts among this population are needed.

AcknowledgementS

New Knowledge Directorate Ltd (www.nkd.org.uk) designed and implemented the web interface and supporting database. The study was funded by the European Commission under the 6th Framework Programme, Contract Nr: LSHC-CT-2006-018702. Richard Bränström is funded by research grants from the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (Nr: 2006-1264 and 2006-0069) and Center for Health Care Science at the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden (Nr: 2008–4737). Nadine Kasparian is supported by a Post Doctoral Clinical Research Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NH&MRC, ID 510399). Julia Newton Bishop is funded by Cancer Research UK Programme grant C588/A4994. Francisco Cuellar was funded by a scholarship (152256/158706) from CONACYT, Mexico. We would also like to thank the following people who have made a significant contribution to the completion of this study; Karolinska Institutet: Katja Brandberg, Ryan Locke; University of Leeds: Faye Elliott; Leiden University Medical Centre: Wilma Bergman, Clasine van der Drift, Coby Out, Evert van Leeuwen, Femke de Snoo; University of Pennsylvania: Patricia van Belle, David Elder, Michael Ming, Nandita Mitra, Lello Tesema; University of Utah: Sancy Leachman.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lens MB, Dawes M. Global perspectives of contemporary epidemiological trends of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(2):179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong BK, Kricker A. The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63(1–3):8–18. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bliss JM, Ford D, Swerdlow AJ, Armstrong BK, Cristofolini M, Elwood JM, et al. Risk of cutaneous melanoma associated with pigmentation characteristics and freckling: systematic overview of 10 case-control studies. The International Melanoma Analysis Group (IMAGE) Int J Cancer. 1995;62(4):367–376. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augustsson A, Stierner U, Rosdahl I, Suurkula M. Common and dysplastic naevi as risk factors for cutaneous malignant melanoma in a Swedish population. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;71:518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh HK, Lew RA. Skin Cancer: Prevention and Control. In: Greenwald, Kramer, Weed, editors. Cancer Prevention and Control. New York: Dekker; 1995. pp. 611–640. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton Bishop JA, Bishop DT. The genetics of susceptibility to cutaneous melanoma. Drugs Today (Barc) 2005;41(3):193–203. doi: 10.1358/dot.2005.41.3.892524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim SF, Brown MD. Tanning and cutaneous malignancy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(4):460–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang Y, Barrett J, Bishop D, Armstrong B, Bataille V, Bergman W, et al. Sun Exposure and Melanoma Risk at Different Latitudes: a Pooled Analysis of 5700 Cases and 7216 Controls. International Journal of Epidemiology in press. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janz NK, Becker Mh. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden J. Health beliefs. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1996. Health beliefs. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology. 1975;91:93–114. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borland R, Marks R, Noy S. Public knowledge about characteristics of moles and melanomas. Aust J Publ Health. 1992;16:370–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1992.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broadstock M, Borland R, Gason R. Effects of suntan on judgements of healthiness and attractiveness by adolescents. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1992;22:157–172. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koblenzer CS. The psychology of sun-exposure and tanning. Clinics in Dermatology. 1998;16(4):421–428. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(98)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandberg Y, Ullén H, Sjöberg L, Holm LE. Sunbathing and sunbed use related to self-image in a randomized sample of Swedish adolescents. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 1998;7(4):321–329. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199808000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branstrom R, Brandberg Y, Holm L, Sjoberg L, Ullen H. Beliefs, knowledge and attitudes as predictors of sunbathing habits and use of sun protection among Swedish adolescents. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10(4):337–345. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bränström R, Ullen H, Brandberg Y. Attitudes, subjective norms and perception of behavioural control as predictors of sun-related behaviour in Swedish adults. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillhouse JJ, Stair AW, 3rd, Adler CM. Predictors of sunbathing and sunscreen use in college undergraduates. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;19(6):543–561. doi: 10.1007/BF01904903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson KM, Aiken LS. A psychosocial model of sun protection and sunbathing in young women: the impact of health beliefs, attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy for sun protection. Health Psychology. 2000;19(5):469–478. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mermelstein RJ, Riesenberg LA. Changing knowledge and attitudes about skin cancer risk factors in adolescents. Health Psychol. 1992;11:371–376. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.6.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vail-Smith K, Felts WM. Sunbathing: college students' knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of risks. College health. 1993;42:21–26. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1993.9940452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wichstrøm L. Predictors of Norwegian adolescents' sunbathing and use of suncreen. Health Psychol. 1994;13:412–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergenmar M, Brandberg Y. Sunbathing and sun-protection behaviors and attitudes of young Swedish adults with hereditary risk for malignant melanoma. Cancer Nursing. 2001;24(5):341–350. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bränström R, Kristjansson S, Ullen H, Brandberg Y. Stability of questionnaire items measuring behaviours, attitudes and stages of change related to sun exposure. Melanoma Res. 2002;12(5):513–519. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veierod MB, Parr CL, Lund E, Hjartaker A. Reproducibility of self-reported melanoma risk factors in a large cohort study of Norwegian women. Melanoma Res. 2008;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f120d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Archives of Dermatology. 1988;124(6):869–871. doi: 10.1001/archderm.124.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boldeman C, Branstrom R, Dal H, Kristjansson S, Rodvall Y, Jansson B, et al. Tanning habits and sunburn in a Swedish population age 13–50 years. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(18):2441–2448. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peacey V, Steptoe A, Sanderman R, Wardle J. Ten-year changes in sun protection behaviors and beliefs of young adults in 13 European countries. Prev Med. 2006;43(6):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monfrecola G, Fabbrocini G, Posteraro G, Pini D. What do young people think about the dangers of sunbathing, skin cancer and sunbeds? A questionnaire survey among Italians. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2000;16(1):15–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2000.160105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koh HK, Bak SM, Geller AC, Mangione TW, Hingson RW, Levenson SM, et al. Sunbathing habits and sunscreen use among white adults: results of a national survey. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(7):1214–1217. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Heckman CJ. Multiple skin cancer risk behaviors in the U.S. population. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanton WR, Janda M, Baade PD, Anderson P. Primary prevention of skin cancer: a review of sun protection in Australia and internationally. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(3):369–378. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillhouse JJ, Adler CM, Drinnon J, Turrisi R. Application of Ajzen's theory of planned behavior to predict sunbathing, tanning salon use, and sunscreen use intentions and behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;20(4):365–378. doi: 10.1023/a:1025517130513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grunfeld EA. What influences university students' intentions to practice safe sun exposure behaviors? J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bränström R, Brandberg Y, Holm L, Sjöberg L, Ullen H. Beliefs, knowledge and attitudes as predictors of sunbathing habits and use of sun protection among Swedish adolescents. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10(4):337–345. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjöberg L, Holm L-E, Ullén H, Brandberg Y. Tanning and risk perception in adolescents. Health, Risk and Society. 2004;6(1):81–94. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marteau TM, Lerman C. Genetic risk and behavioural change. Bmj. 2001;322(7293):1056–1059. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7293.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Starr P, Dietrich AJ. The impact of an appearance-based educational intervention on adolescent intention to use sunscreen. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(5):763–769. doi: 10.1093/her/cym005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Long-term effects of appearance-based interventions on sun protection behaviors. Health Psychol. 2007;26(3):350–360. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Harrell J, Correa A, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Effects of UV photographs, photoaging information, and use of sunless tanning lotion on sun protection behaviors. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(3):373–380. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hillhouse JJ, Turrisi R. Examination of the efficacy of an appearance-focused intervention to reduce UV exposure. J Behav Med. 2002;25(4):395–409. doi: 10.1023/a:1015870516460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, Robinson J. A randomized controlled trial of an appearance-focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3257–3266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DiSipio T, Rogers C, Newman B, Whiteman D, Eakin E, Fritschi L, et al. The Queensland Cancer Risk Study: behavioural risk factor results. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30(4):375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eiser JR, Eiser C, Sani F, Sell L, Casas RM. Skin cancer attitudes: a cross-national comparison. Br J Soc Psychol. 1995;34(Pt 1):23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]